Daniel Simons's Blog, page 2

May 2, 2011

Invisible Gorilla Charity Campaign

The Goal

To celebrate the upcoming release of the paperback edition of The Invisible Gorilla (on June 7), Chris and I are starting a charity campaign; we're going to be supporting some charities whose missions relate to some of the topics we discuss in the book. We decided we would rather have our money go toward good causes than toward a PR firm or more traditional marketing campaign. Of course, we're also hoping that people will pre-order our book. So, we hatched a plan that we hope will accomplish both goals and will be a win-win both for our book and for some great charities. (Of course we also hope it will be a win for our readers!)

The Plan

For every copy of the paperback edition that people pre-order or purchase by June 11, we will donate $5 to a charity they select. Over the course of the campaign, we plan to donate up to $25,000 in total. At the end of the campaign, we will donate a bonus $2000 to the charity selected by the most people.

The Charities

We have selected a number of charities that emphasize science, education, safety or other themes that are relevant to the topics in our book. You can see a list of the charities and what they do here. We may add a few more to the list over the coming weeks.

Want To Participate?

It's easy! Just go to our charity promotion page for step-by-step instructions. All you have to do is pre-order the book (we provide links to make it easy), provide some basic information about your purchase, and select the charity you would like us to support. That's it! We take it from there. The book is currently selling for about $10 online at the major booksellers, so it's a great way to get an inexpensive copy of the book and to help support a charity at the same time. (And, if you would like to, you can also enter a drawing to win a gorilla suit.)

Please help us support these worthwhile causes! You can help even more by spreading the word about this charity campaign. Please feel free to forward or cross-post this message.

April 30, 2011

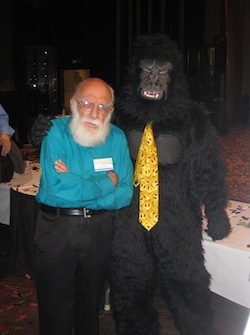

More stuff to do with a gorilla suit

Yesterday I posted about our gorilla suit promotion for the forthcoming paperback edition of The Invisible Gorilla. If you pre-order the book, you have a chance to win your very own gorilla suit. Go here for details. In that post, I gave a few suggestions for things you could do with a gorilla suit. Here are a few more:

Go shopping for bananas:

Chase a banana at the beach

Chase a banana on skis

Hang out with The Amazing Randi:

April 28, 2011

Win a gorilla suit

Wouldn't you like to have your own gorilla suit? In the first of several promotions for the forthcoming paperback edition of The Invisible Gorilla, we have teamed up with HalloweenCostumes.com to raffle off a deluxe gorilla costume!

All you have to do is pre-order a copy of the paperback of The Invisible Gorilla. To learn more, just go to www.theinvisiblegorilla.com/gorillapromo.html.

If you need more enticement, just imagine what you could do with your own gorilla suit. Here are a couple suggestions:

Give a presentation to your colleagues at a professional meeting:

Wander around town to see how people react to you:

Surprise people by sneaking up behind them:

The possibilities are endless. Feel free to add your own suggestions in the comments.

April 27, 2011

Invisible Gorilla Paperback!

We're excited to announce the paperback edition of The Invisible Gorilla

It will be released into the wild on June 7

(assuming North America counts as wild).

You can pre-order it now.

Stay tuned for upcoming announcements and promotions.

April 21, 2011

gorillas, working memory, and the media

This week you might have seen some coverage resulting from a press release out of the University of Utah about a new inattentional blindness study by Seegmiller, Watson, & Strayer. Here are some example headlines resulting from the press release:

Why we don't see what's right in front of our eyes

Researchers solve the case of the invisible gorilla

(I'm not quite sure I understand the last one. Do Brit's really have a new dance move that involves chest thumping? If so, please do tell.)

The implication of these headlines are: (1) that some people typically experience inattentional blindness and others don't, and (2) that the new study entirely explains such individual differences. Both implications are false. The first is entirely unsubstantiated and the second is a massive overextension of what actually is an interesting result. The actual study, the press release, and the subsequent media coverage make a nice case study to explore how media coverage of science can create a false understanding among non-scientists about the nature of scientific inquiry.

The media is reacting to the finding that, under some conditions, differences in working memory capacity predict noticing of an unexpected gorilla. They over-generalize the finding to suggest that people who are high in working memory capacity are immune to inattentional blindness.

A look at the findings and their scope

So what did the new paper actually find? If you give people a highly demanding version of the basketball-gorilla task (separately count the aerial and bounce passes by the players wearing black) and exclude subjects who were unable to do the counting task well, those subjects remaining who scored highest on a measure of working memory were more likely to notice the gorilla than were those subjects scoring low on the working memory measure. Even with those constraints, working memory differences only help a little bit in predicting who will notice.

Let's take a step back and look further at those constraints. First, the study used a difficult task — keeping track separately of bounce passes and aerial passes — that likely taxes both working memory and attention. It's possible that working memory capacity only predicts noticing when the task is particularly taxing and not in the more common case in which the primary task is relatively easy. Given that inattentional blindness has been documented across groups that differ widely in intelligence and presumably in working memory capacity, the predictive value of individual differences in working memory capacity might be limited to a fairly small subset of cases for which attention and memory are particularly strained. From the result, we just don't know whether the demands of the task actually matter. My guess is that they do.

Second, when including all of the subjects in the analysis, individual differences in working memory did not predict noticing. You read that right. Overall, working memory capacity was unrelated to noticing. In order to reveal an effect of working memory on noticing, the authors first excluded anyone who counted the passes with less than 80% accuracy (that percentage is somewhat arbitrary, but fine). The logic for the restriction is reasonable—people might give up counting in the middle of the task if they happen to notice the gorilla, and people who don't bother counting might also notice the gorilla for uninteresting reasons. The authors justifiably argue that such contaminating factors might obscure a relationship between working memory and noticing. But, the choice of cutoffs could well influence the resulting relationship, and the lack of an overall relationship means that you can't predict who will notice and who won't just by measuring working memory capacity.

I think there might be a more theoretically interesting reason why the authors found an effect of working memory capacity on noticing in those subjects who accurately counted passes, one that further limits the scope of the relationship: People were counting passes by the players wearing black, and the unexpected object was also black.

Typically, more people notice the gorilla when counting passes by the players wearing black than when counting passes by the players wearing white. The authors suggest in a footnote that with a video like this one—although not the exact one they used—the difference in rates of noticing isn't huge. My concern is not about the difference in noticing rates (although they typically are about 20% more likely to spot the gorilla when counting players by the black team). My concern is about how attending to the black players might produce a correlation between noticing and working memory.

When focusing on the players wearing black, people have an attention set for black, and the gorilla falls into that attention set (i.e., it is black as well). It's possible that people with high working memory capacity are more likely to notice other items matching their attention set than are people low in working memory capacity. That is, their spare capacity helps them incorporate other aspects of a scene that are consistent with their focus of attention. In other words, they only had an advantage in noticing because the gorilla shared features with the people they were attending. If true, there should be no effect of working memory if the unexpected object were more similar to the ignored items. The relationship between working memory and inattentional blindness revealed by the experiment might only apply in that special case in which the unexpected object happens to share the attended feature (black color) with the attended items (players wearing black). I would actually predict that there will be no relationship whatsoever between working memory and noticing if the unexpected object is different from the attended items on the critical attended dimension.

Implications for science and the media

The paper is among the first to carefully explore whether individual differences in working memory contribute to inattentional blindness. I think this is an interesting and intriguing result, one that shows how individual differences in cognition affect inattentional blindness, at least under some conditions. The paper carefully acknowledges prior work and does hedge its claims (although a little more hedging might have been merited in places). It is laudable for its rigor, including large enough samples to look for individual differences and controlling for factors that might have masked evidence for a link between working memory and noticing in the past.

So how did the media coverage take this interesting, but potentially limited-in-scope result and infer that the study somehow solved the case of the invisible gorilla? Any scientist reading the journal article would recognize that the correlation between working memory and noticing is imperfect and would separate speculative conclusions from definitive results. Unless the press release makes those limitations explicit, the media will not either. Unless the press release explicitly identifies the limited scope and imperfect correlation and flags speculation as such, an untrained reader (or headline writer) will naturally infer that the result and the speculation are one and the same. In this case, they will infer that working memory differences explain inattentional blindness in its entirety. By not reigning in the speculation, the release suggests that the working memory is the primary (if not the only) reason that some people notice and some people miss unexpected objects.

This mistaken inference is dangerous. Everyone is subject to inattentional blindness because we all have limits on our attention capacity. Nobody is immune to the effects of inattentional blindness, and many people who were high in working memory capacity missed the gorilla, even under the conditions tested in this study. This is an important new finding, but it does not justify broad claims that working memory explains inattentional blindness in general. Perhaps these working memory effects will generalize to other tasks and contexts, but we don't know that yet (and I have reasons to doubt they will generalize to all inattentional blindness tasks).

Scientists understand the value of a strong claim. Speculation based on an initial finding can drive new research designed to test or refute strong claims. Over time, and across many studies, the field settles on a more nuanced understanding. The problem comes when an initial strong claim and the associated speculations are presented to the public as definitive conclusions. If later studies reveal the limits and scope of the relationship between working memory and noticing, and press releases tout the relative lack of individual differences, the public will perceive the combined results as contradictory. That hurts the perception of science in general. If one day chocolate is bad for you and the next it is good for you, people assume that they can just choose what to believe because scientists really don't have a clue. In some cases, scientists might well be clueless. But, in most cases, strong claims from preliminary evidence are not a sign of cluelessness but of a desire to make interesting findings known to the scientific community so that they can be refined. I'm fine with speculation in journal articles. Most media outlets don't read the original scientific paper anyway. My concern is with overly strong claims pushed as definitive evidence in press releases that are designed to grab media coverage. To the extent that they can control the publicity process, scientists must reign in the speculative conclusions in their press releases, noting the limits of their evidence. If we're lucky, press releases might even convey more basic information about such limits, thereby giving the public a more nuanced view of the scientific process.

Source Cited:

Seegmiller JK, Watson JM, & Strayer DL (2011). Individual differences in susceptibility to inattentional blindness. Journal of experimental psychology. Learning, memory, and cognition PMID: 21299325

March 25, 2011

Seeing the world as it isn't

An earlier version of this post appeared on my Psychology Today blog on April 30, 2010.

When we look at the world around us, we feel that we are seeing it as it is. Most of the time, we are — but not because our visual system perceives the world precisely as it is. Rather, our visual system makes informed guesses about the contents of the world based on the compressed signal projected onto our eyes. And, for most practical purposes, those guesses are pretty good. Moreover, this "guessing" system work so seamlessly that we rarely notice any discrepancy between our guesses and reality. Only when we "break" the system can we reveal these default assumptions.

My 7-minute long talk at TEDxUIUC in February 2011 explains why we have to break the visual system to understand how it works. As an added bonus, I showed some terrific illusions and demos from Julian Beever, Bart Anderson, and Bill Geisler. Check it out:

Just as we can't intuit the mechanisms of vision, we lack insight into the mechanisms of memory, reasoning, and thinking. Only when forced to confront what we're missing do we realize that we've unwittingly made assumptions. We often have no idea how limited our abilities can be. The following change blindness video illustrates one such limitation:

When Dan Levin and I conducted that person-change study, we found that about 50% of people didn't notice they were talking to a different person. That sort of person-change rarely (if ever) happens in the world. You might assume, without doing the study, that people actually keep track of all of the details of the people they interact with. Only by making a change can you reveal the extent of their change blindness. In fact, people who missed the change would never have known anything was amiss had we not asked them. This effect reveals what Chris Chabris and I call the "Illusion of Memory" — we think we remember far more than we actually do.

This sort of cognitive, everyday illusion is akin to a visual illusion. When you view a visual illusion, you are seeing the world as it isn't — the illusion capitalizes on one of the shortcuts your brain takes when processing visual information, with the result that you see the world the way you assume it to be rather than the way it actually is. With cognitive illusions like change blindness, we think we see and remember far more than we actually do because we are unaware of the shortcuts our brain takes when representing the world. For the most part, we simply assume the world to be unchanging, and typically we're right. We just don't realize we're making that assumption.

Source cited:

Simons, D. J., & Levin, D. T. (1998). Failure to detect changes to people during a real-world interaction Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 5, 644-649 : 10.3758/BF03208840

March 22, 2011

Chess as an analogy for science

In this video, Richard Feynman explains the process of scientific discovery via an analogy to an observer "discovering" the rules of chess. This is science communication at its best:

March 1, 2011

Invisible gorilla makes an appearance

We're really excited that The Invisible Gorilla will be published in the Netherlands this April. Even cooler, I will be in the Netherlands to speak at PINC in May and will get to see the book in stores there!

Our publisher sent this wonderful image of a not-so-invisible gorilla at a book fair helping to promote the Dutch edition of the book to booksellers and the media by walking around the fair with a copy of the book an handing out postcards. Apparently, all the postcards were snapped up in minutes.

photo: Gerlinde de Geus

February 28, 2011

another 'invisible gorilla' anecdote

I've had a little hiatus from posting for the past month as I worked to start up the ionpsych blog for my graduate seminar on speaking and writing for a general audience (check out the site, by the way — some terrific posts about psychology and the mind/brain). I hope to post a bit more frequently over the coming weeks. Lots of really interesting science to write about.

In the meantime, here is an interesting anecdote sent in from a reader about a personal "invisible gorilla." (for other examples, see my earlier posts here, and here and here. Check the comments for other examples from readers). It illustrates how we see what we expect to see.

I was out shopping with my 3 children all under the age of 6. After gathering all items on the shopping list we headed to the checkout. As a parent you continually check the children and all were in tow. I placed 2 items from the trolley onto the counter. I then turned around and the youngest had gone. In today's society this is a slightly anxious moment for any parent. In a slight panic I ran to the first aisle, but he was not there. As I was heading down to the second aisle a lady came round the corner carrying a child, the child was not screaming or struggling, so I went to continue moving down the next aisle. I had to physically stop myself and double check if this was my child….unreal………..as I was looking at the child my mind was still focused on finding my child running.

Scary part of this invisible gorilla, I was looking for my child who was running away, not being carried by another person in a calm manner. If there had been additional variables it is very understandable how someone could miss something in front of them, even when looking directly at what they are looking for.

Has anything like that happened to you? Have you ever looked right at something and not seen it for what it is? If so, I'd love to hear about it (in the comments or by email).

February 14, 2011

Cute animation for German edition of Invisible Gorilla

The German translation of The Invisible Gorilla will appear this spring, and the publisher has added a cartoon gorilla to each page of the book. If you flip through the pages, the gorilla walks across the book, thumps its chest, and walks back (animation designed by Oliver Weiss). Pretty clever. We haven't yet seen the effect in person, but we think this video from the publisher shows what it looks like:

We're slowingslowly adding cover art for all of the forthcoming translations of the Invisible Gorilla to our international editions page. You can also see a gallery of the cover art on our facebook page. The book is now out in Russian and Chinese (simplified) and will be appearing this month in Japanese and Korean.

Update: The Japanese edition was published on February 3, and cover art was added to our international editions page.

Daniel Simons's Blog

- Daniel Simons's profile

- 28 followers