Daniel H. Pink's Blog, page 14

August 22, 2011

How to understand regret — and 2 ways to avoid it

Sometimes when I'm stuck on a course of action, I use two techniques to help me decide.

Sometimes when I'm stuck on a course of action, I use two techniques to help me decide.

One is what I call the "90-year-old me Test." I imagine I'm 90 and looking back at the decision before. What will I want to have done in this situation? In most cases, the 90-year-old me wants today's me to take an intelligent risk rather than to avoid one — and to act nobly rather than like an ass.

The other I call the "Viktor Frankl Test." In his book, Man's Search for Meaning, Frankl advises: "Live as if you were living for the second time and had acted as wrongly the first time as you are about to act now."

Both techniques are forms of what we might think of as "regret management." They're based on the idea that one key to decision-making is to avoid subsequent regret.

That's why I was intrigued by a new study that fluttered into Pink, Inc., world headquarters during a recent vacation. In it, Mike Morrison of the University of Illinois and Neal J. Roese of Northwestern asked 370 Americans about their lives' deepest regrets. Here's a quick summary of the results, some of which surprised me:

"Lost loves and unfulfilling relationships turned out to be the most common regrets," though women had far more romantic regrets than men. Family matters were the second greatest source of regret.

Men were more likely to have work-related (career, education) regrets than women. And in an interesting paradox, "Americans with high levels of education had the most career-related regrets." In other words, more options seemed to correlate with more regrets.

Overall, there wasn't a difference between regrets over actions taken versus actions not taken. Prior research had shown that regrets focusing on action were more common than those focusing on inaction. But people regretted inaction far longer than actions.

At the risk of turning this into an online therapy session, I'm curious to know what sorts of things you regret — and what techniques you use to avoid or mitigate it. Add your voice to the Comments section, which one reader recently told me "was better than the blog itself." (BTW, I don't regret that for a moment.)

August 9, 2011

Why progress matters: 6 questions for Harvard's Teresa Amabile

Here's a tip for rounding out your summer reading. Pick up a copy of The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement, and Creativity at Work. The book, which pubs today, is one of the best business books I've read in many years. (Buy it at Amazon, BN, or 8CR).

Here's a tip for rounding out your summer reading. Pick up a copy of The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement, and Creativity at Work. The book, which pubs today, is one of the best business books I've read in many years. (Buy it at Amazon, BN, or 8CR).

The authors — Harvard B-school professor Teresa Amabile and developmental psychologist Steven Kramer (yep, they're married) — explored the question of when people are motivated and engaged at work.

And to do that, they took a rigorous and painstaking approach. They recruited 238 people across 7 companies — and each day sent these folks a questionnaire and diary form about their day. Twelve thousand diary entries later — you read that right: Amabile and Kramer amassed 12,000 days worth of data — they reached a set of fascinating conclusions.

Chief among their findings: People's "inner work lives" matter profoundly to their performance — and what motivates people the most day-to-day is making progress on meaningful work.

I asked Amabile if she'd answer some questions for Pink Blog readers about her book and her insights. You can read the interview below. You can also talk to her live later this month on the next episode of Office Hours.

***

Lots of business books talk about the need for bold, audacious goals — and deride those who "think small." But your book, which is based on research far more rigorous than its counterparts, takes a different stance. You emphasize the power "small wins." Why are those so important in the performance of individuals and organizations?

Try to remember the last time you – or anyone you know – had a truly enormous breakthrough in solving a problem or achieving one of those audacious goals. It's pretty hard, because breakthroughs are very rare events. On the other hand, small wins can happen all the time. Those are the incremental steps toward meaningful (even big) goals. Our research showed that, of all the events that have the power to excite people and engage them in their work, the single most important is making progress – even if that progress is a small win. That's the progress principle. And, because people are more creatively productive when they are excited and engaged, small wins are a very big deal for organizations.

In addition to examining 12,000 daily diary entries from workers, you also surveyed a few hundred leaders — from CEOs to project managers — about what they think really motivates employees. What did you find out?

Our survey showed that most leaders don't understand the power of progress. When we asked nearly 700 managers from companies around the world to rank five employee motivators (incentives, recognition, clear goals, interpersonal support, and support for making progress in the work), progress came in at the very bottom. In fact, only 5% of these leaders ranked progress first – a much lower percent than if they had been choosing randomly! Don't get me wrong; those other four motivators do drive people. But we found that they aren't nearly as potent as making meaningful progress.

Along those lines, many bosses believe that best way to ensure top performance is to keep their charges on edge — hungry and a little stressed-out. But you found something different. Explain.

If people are on edge because they are challenged by a difficult, important problem, that's fine – as long as they have what they need to solve that problem. But it's a dangerous fallacy to say that people perform better when they're stressed, over-extended, or unhappy. We found just the opposite. People are more likely to come up with a creative idea or solve a tricky problem on a day when they are in a better mood than usual. In fact, they are more likely to be creative the next day, too, regardless of that next day's mood. There's a kind of "creativity carry-over" effect from feeling good at work.

Yet negative events have a more powerful impact than positive ones. Why?

We were pretty shocked to discover the dominant effect of negative events on inner work life – people's mostly-hidden emotions, perceptions, and motivations at work. Setbacks have a negative effect on inner work life that's 2-3 times stronger than the positive effect of progress. When we checked into whether other researchers had found something similar, we learned that it's a general psychological effect; "bad is stronger than good." The reason could be evolutionary. Maybe we pay more attention to negatives, and are more affected by them, out of self-preservation. So – because positive inner work life is so important for top performance, leaders should do whatever they can to root out negative forces.

I was especially intrigued by your findings about time pressure. Sometimes it helps; other times it hurts. Tell us what you found.

The typical form of time pressure in organizations today is what we call "being on a treadmill" – running all day to keep up with many different (often unrelated) demands, but getting nowhere on your most important work. That's an absolute killer for creativity. Generally, low-to-moderate time pressure is optimal for creativity. But we did find some instances in which people were terrifically creative under high time pressure. Almost invariably, it was quite different from being on a treadmill. Rather, people felt like they were "on a mission"— working hard to meet a truly urgent deadline on an important project, and protected from all other demands.

What are one or two specific things individuals can do to improve their inner work lives and increase their chances of making progress on meaningful work?

Religiously protect at least 20 minutes – and, ideally, much more – every day, to tackle something in the work that matters most to you. Hide in an empty conference room, if you have to, or sneak out in disguise to a nearby coffee shop. Then make note of any progress you made (even if it was a small win), and decide where to pick up again the next day. The progress, and the mini-celebration of simply noting it, can lift your inner work life.

What are one or two things bosses can do to re-architect the workplace and its policies to put progress at the center?

Bosses can religiously protect at least 5 minutes, every day, to think about the progress and setbacks of their team, and what enabled or inhibited that progress. The daily review should end with a plan to do one thing, the following day, that's most likely to facilitate progress – even if that progress is only a small win. I think this practice, if used widely, could make a real difference in organizational performance and employee inner work life. And good inner work life isn't only a matter of employee retention or the bottom line. It's a matter of human dignity.

August 2, 2011

The future of education . . . 100 years ago

The intrepid Maria Popova — BTW, if you're not subscribing to her newsletter or following her on Twitter, you should — points to a really interesting item in How to Be a Retronaut.

The intrepid Maria Popova — BTW, if you're not subscribing to her newsletter or following her on Twitter, you should — points to a really interesting item in How to Be a Retronaut.

The Retronaut blog, which collects artifacts from the past to help us understand the present, unearthed an article from Ladies Home Journal circa. 1900, headlined, "What May Happen in the Hundred Years." Its author, one John Elfreth Watkins, Jr., lays out his predictions for the American life in the early 21st century.

Among his calls: Americans will be taller. (True) There will be no C, X, or Q in the alphabet. (False) Photographs will be telegraphed from large distances. (True) Rats and mice will be gone. (False). Pneumatic tubes, instead of store wagons, will deliver packages and bundles. (False, but Amazon is working on it.)

But somehow I found his predictions for "How Children Will Be Taught" most compelling. Here's what he says:

A university education will be free to every man and woman. Several great national universities will have been established. Children will study a simple English grammar adapted to simplified English, and not copied after the Latin. Time will be saved by grouping like studies. Poor students will be given free board, free clothing and free books if ambitious and actually unable to meet their school and college expenses. Medical inspectors regularly visiting the public schools will furnish poor children with free eyeglasses, free dentistry, and free medical attention of every kind. The very poor will, when necessary, get free rides to and from school and free lunches between sessions. In vacation time, poor children will be taken on trips to various parts of the world. Etiquette and housekeeping will be important studies in the public schools.

Your thoughts?

July 27, 2011

A 30-second test to determine whether your boss is a gem or a jerk

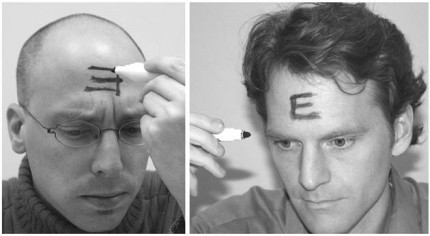

Let's say you and I are talking in person — and I make a strange request: "Take your right forefinger and draw a capital E on your forehead."

There are two ways to do that, of course. You can draw like the guy on the left or like the guy on the right.

But which choice you make might say a lot about what kind of boss you are. It's all explained in this Sunday Telegraph column, which draws on pioneering research led by Northwestern University's Adam Galinsky (a name all you social psych nerds should be keeping an eye on and who also happens to be the guy on the left.)

Photo credit: Adam Galinsky, Blackwell Publishing

More emotionally intelligent parking lot signage

David Giltner sends this sign, which "was posted in the parking lot of a coffee shop that is adjacent to an elementary school in Lyons, CO."

July 18, 2011

The Genius Hour: How 60 minutes a week can electrify your job

Lots of people believe that a single individual can't make a difference in an organization.

Lots of people, it turns out, are wrong.

Take the case of Jen Shefner. She's an assistant vice president at Columbia Credit Union in Vancouver, WA, in charge of the credit union's online and mobile services. Last month I met her at a conference, and she told me about a smart and simple innovation that she calls the "Genius Hour."

Jen grooved on Google's 20% time and Atlassian's Fedex Days – and wanted to bring that sort of noncommissioned work to her department. Trouble is, the three folks on her staff handle phone calls and requests from credit union members and internal customers. They have to be available throughout the day. Breaking away for a 24-hour FedEx Day or an afternoon passion project – and leaving customers with an endlessly ringing help line – is a nonstarter. So Jen fashioned a solution.

Each week, employees can take a Genius Hour — 60 minutes to work on new ideas or master new skills. They've used that precious sliver of autonomy well, coming up with a range of innovations including training tools for other branches.

Of course, an hour a week for every employee isn't much time. But it's an hour more than most of us get. And Jen makes it work for at least three reasons.

The boss pitches in. Who answers the phone when an employee is on a Genius Hour? Jen does. That's right. Jen steps up and does her staff's jobs so they have time to do big think work. Imagine if all managers showed that level of integrity and commitment.

Implementation matters. Jen admits that "it's hard for our industry to see ways to offer autonomy," and for good reason – credit unions are highly regulated and by necessity must be conservative. As a result, good ideas often blossom – and then wither from inaction. Jen works like a fiend to see that the best ideas get implemented.

It's on the schedule. Genius Hours aren't ad hoc. They're fixed on the departmental calendar. The hour, if not exactly sacred, is semi-sacred. In most organizations what gets scheduled gets done. Genius Hours get scheduled, which why they get done.

"Great ideas come from every level," Jen says. But she's too modest to suggest that the Genius Hour itself is a great idea. It is.

When are you going to give it a try?

July 7, 2011

Don't be an ***hole. Listen to Office Hours

The Office Hours freight train is steaming into July.

The Office Hours freight train is steaming into July.

Please join us for our next episode — Wednesday July 12 at 2pm Eastern time. Our guest will be Bob Sutton — the Stanford Business School professor, uber-blogger, and author of several great books, including one whose full title I can't mention on a family website.

For the uninitiated, Office Hours is our latest experiment — a radio-ish show in which I open the phone lines for an hour to listeners around the world, who can ask me and a special guest anything they want about work, business, life, or any other topic. As we say, it's Car Talk . . . for the human engine.

To listen in live or to ask a question of your own, just use the call-in details on our Office Hours page, where you can also hear our previous episodes with guests David Allen and Seth Godin. And while you're there, sign up to be notified about upcoming episodes. Of course, the whole thing is free of charge and free of advertising. (Our business model is to lose money on every episode, but make it up in volume.)

Also, for you folks with those newfangled iDevices, I'm happy to announce that Office Hours is now on iTunes. Check it out here.

July 6, 2011

Why do we care about some things and not others?

Joe F. is a high school teacher in New York who emailed recently with a pair of interesting questions. In fact, they were so intriguing that I asked Joe if I could present them to Pink Blog readers for their responses.

Joe F. is a high school teacher in New York who emailed recently with a pair of interesting questions. In fact, they were so intriguing that I asked Joe if I could present them to Pink Blog readers for their responses.

Here is Joe's explanation, followed by his questions:

Our school holds an annual holiday volleyball tournament in phys ed class. Every student participates, and even the athletically uninclined risk dignity and limb diving into bleachers to save a point. The reward for winning is nothing, yet they care at a near super-human level.

Many JV and some Varsity coaches have complained that their athletes do not care as much about their varsity sport as they do this tournament.

1) Why?

2) What can varsity and JV coaches do to build/foster this measurable effort in their sports?

Okay, folks, what do you think? Offer your answers in the Comments section. I'll collect the best and include them in a separate post.

July 5, 2011

How to deliver innovation overnight

One of the ideas in Drive that has spread the fastest and the widest is the FedEx Day. Invented by the folks at the Australian software company Atlassian, these one-day bursts of autonomy allow people to work on anything they want (as long as it's not part of their regular job) — provided they show what they've created to their colleagues 24 hours later. Atlassian dubbed these innovation jamborees FedEx Days because participants have to deliver something overnight.

One of the most recent adopters of this technique is the Dutch company, PAT Learning Solutions, which held a FedExDay last month. To get a sense of how it worked, check out this 4-minute video by Rini van Solingen, the first 3:30 minutes of which are pretty good.

Then take a look at this blog post by PAT's Rob van Lanen, in which he enumerates some of the benefits, including these:

Almost all developers participated.

Participants were completely self-organizing. No interventions from management.

A lot of developers were working late for their project. Three of them even spent the night in their sleeping bag at our company (!).

Feedback from non-IT colleagues was very positive. I am sure we will have another FedEx day in a few months, possibly with more non-IT colleagues joining.

One of the projects, a traffic light information radiator for our build server is up and running!

Regular readers know that I'm convinced that "noncommissioned" work such as FedEx Days will soon become commonplace. So maybe it's time to ask yourself not, "Should I try something like this?" — but "Why am I not doing this already?"

June 28, 2011

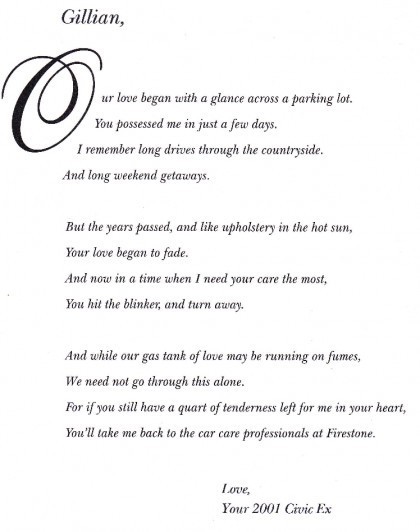

When was the last time you received a love poem from your car?

For most of us, the answer is never.

For Gillian McCarthy of Los Angeles, the answer is last Thursday.

Back in 2001, McCarthy bought a green Honda Civic Ex from a local dealership. She's taken good care of it — but perhaps not good enough. So last week, in the mail, she received this:

Emotionally intelligent car care? Literary anthropomorphic marketing? Sniff, sniff. I smell a meme.

Emotionally intelligent car care? Literary anthropomorphic marketing? Sniff, sniff. I smell a meme.