Nancy I. Sanders's Blog, page 76

March 15, 2013

How Many Words in a Published Book

Okay, some of you may already know this, but I just learned this today.

There’s a site you can go to if you want to find out how many words are in a published book.

Why, you may ask, would a writer want to know that?

Because it really really really helps to know if you’re evaluating a book in a genre or market you want to write.

For example, I’m in the middle of hosting a picture book mentoring workshop in my home. We’re studying and evaluating 3 picture books. At one point we wanted to know the word counts of these books, so we counted them. Yup. Word for word. (Thanks to one of our gals who counted 2 of them all by herself!!!)

No more!!!

Now I’ll just visit this handy dandy site, and search for the book’s title to see how many words are in the book. Whew! Easy Peasy!

Here’s the site:

Okay…tell me if you already knew this and you’ll earn 5 bonus points for the day!!!  )

)

March 12, 2013

Writer’s Workshop: Beginning Readers

Wanna join in on the fun? Today and for the next 3 days, I’m the guest of Jan Fields, awesome moderator for free workshops with the Institute of Children’s Literature!

You can come join in the exciting chats (for free) by first clicking on this link to see how this works:

How our Board Workshops Operate

Here’s a tad bit more info on this workshop:

Writer’s Retreat Workshop

BEGINS TUESDAY

March 12-14, 2013 “Beginning Readers” with Nancy Sanders

Join us for help with writing for children who are just beginning to read — learn about the needs of the children, the editors and the publishers for them!

And we’re also talking about my new book for children’s writers:

Yes! You Can Learn How to Write Beginning Readers and Chapter Books

March 8, 2013

Genre: Teen Romance, Part 2

How This Genre Influences Your Plot

The plot in a teen romance progresses from beginning to end following events influenced by the different stages of love, specifically from a teen’s point of view. Since character development and the character’s internal emotions are paramount, a teen romance often follows a character-driven plot. Simply put, this means that the significant changes that occur in your main story plot to transition the story from the beginning to the end will be reflected in the big internal changes the main character is experiencing.

Before you plan the key events in your story’s plot, spend time considering whether you want to write in this genre alone or not. Do you want to write a true teen romance? Or do you want to mix and match this genre with another? For example, you could write a historical romance for teens. Your main character could be traveling the Oregon trail, fall in love with the wagon leader’s oldest son, and become a teen bride at 17. Or you could write a teen paranormal romance such as Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series. Your main character could fall in love with the captain of the football team only to discover he’s actually a vampire. You could even write a dystopian romance where your main character is banished by the government to a prison camp for rebellious citizens where she falls in love with a brave teen boy who is a member of her chain gang.

As you’re planning the key events in your story’s plot, you may realize that you don’t want to write in this genre at all. Sure, you want to include romance in your YA novel, but you realize you don’t want it to take center stage is it needs to be if you’re writing in this genre. You may want to write literary fiction or an adventure instead. If this is the case, you can still pick teen romance as a universal theme and develop it as a subplot within the genre you choose.

It’s a delicate balancing act for any writer who chooses to include romance in a story for children or teens. Because romance can so easily dominate the story (or not influence the plot as it should if it isn’t developed correctly) it’s important to decide during the planning and plotting stages what role you want romance to take. It will save you a lot of angst as a writer if at the start, you choose carefully whether or not you want to write a true teen romance, mix and match teen romance with another genre, or incorporate romance solely as a universal theme that develops as a subplot among the different layers of your story. Plot out the key events and significant changes of your story accordingly before you start to write, and you’ll be well on your way to maintaining the proper balance of romance your story needs. You’ll appear as professional as a tightrope walker at the circus balancing on a bike while seemingly riding effortlessly across the high wire!

March 6, 2013

Genre: Teen Romance, Part 1

The focal point of every child’s world is love. As an infant, this love centers on family, especially mommy or daddy. In the toddler years, this circle widens to include genuine love for a blankie or favorite teddy bear. By early elementary age, children love their buddies and best pals. And as they grow up through the preteen and teenage years, even though family and friends still hold the key to their hearts, it’s the natural progression of the maturation process for middle graders and young adults to reach toward adulthood and the idea of getting married. Just as toy make-up kits are replaced with lipstick and rouge, fairytale picture books with castles, a princess, and Prince Charming are replaced with teen novels.

This genre works most effectively if you want to write for the young adult (YA) market rather than books or stories for younger readers. Young adult novels are geared for a target age of teenage readers who are 13 to 19 years old. Hence “teen” romance. These are the years when many kids become interested—seriously interested—in each other and discover the emotional rollercoaster called love. Many of them turn to reading teen romances because it’s a safer way to explore and learn about these new emotions they’re feeling instead of climbing on the rollercoaster itself.

Even though you can have romance in a middle grade (MG) novel, chapter book, or magazine story for younger readers, it usually takes the role of a universal theme that’s developed through a subplot within the category of a different genre such as mystery or science fiction. For younger readers, romance often takes the form of a first crush or puppy love rather than a fully developed romance, simply because most readers twelve years old or younger aren’t interested or even aware of serious romance. And if they are, chances are they’ll choose YA novels to read where the characters are slightly older than themselves. Because there isn’t a strong audience for romance in younger readers, many publishers stick with the genre of teen romance in the YA market.

In a teen romance, a significant event in the plot occurs when the princess and her prince charming meet. Or, if they already know each other, this event occurs when they first become aware of each other at a more significant level. It can be love at first sight or they can start out as enemies, but there needs to be a problem they have to struggle with that will either bring them closer together or drive them farther apart. Throughout the middle of the story, they can deal with love’s ups and downs as their relationship deepens and they become more intricately intertwined with each other. Few teen romances actually end in marriage since the characters, after all, are still teenagers, but endings in a teen romance can be anything from tragic to bittersweet to hopeful with the promise of a committed and love-filled relationship.

March 4, 2013

Genre: Mystery

Many kids love trying to solve a riddle. Develop a riddle into a story with a main character sleuth who has huge doses of kid appeal, and you’ve got a winning mystery in your hands. A mystery is like a puzzle where children get to pick up each piece and figure out how it fits into the whole story plot.

In a children’s story, a mystery often has a main character who attempts to solve the puzzle. If not the main character, the main character invites or calls on a supporting character to help solve the riddle. In a series such as a magazine series, beginning reader series, or middle grade novel series such as the Cam Jansen books by David A. Adler, the main character is often a child detective or a group of children or teens who have set up their own detective agency. However, in a stand-alone book such as From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E. L. Koningsburg, the main character (or characters) might be ordinary children forced into a situation where there’s a mystery that needs to be solved.

Along with a detective or sleuth who attempts to solve the mystery, there is a trail of clues to follow. There are suspects, or other characters, who have real or imagined motives and opportunities for being the guilty culprit. There can be witnesses, or characters who observed various events. There can be a red herring, or false clue, that takes the detective down a bunny trail momentarily leading away from the actual solution. At the end of the story, the mystery is usually solved in a satisfying way that makes sense to your reader.

In a mystery, the riddle or puzzle becomes the main story problem that the main character attempts to solve. In mysteries for children in early elementary school, these puzzles often deal with the everyday world of a child. The kid (or animal) detective might be called upon to solve the mystery of the missing dog food, the stolen lunchbox, or the mixed-up homework. For stories geared to students in middle grade or high school, the mysteries become more threatening and realistic and can deal with actual crime or even murder.

How This Genre Influences Your Plot

If you choose to write in this genre, it will greatly impact your plot. If you choose to write a mystery, the puzzle to solve becomes the main story problem. The series of events that occur in your plot become the series of attempts the detective makes to try to solve the mystery.

March 1, 2013

Genres: On Overview

The two main genres are fiction and nonfiction. Nonfiction is 100% true. Any manuscript that includes ingredients of make-believe is classified under fiction. Even if a lot of the facts are true, if some of it’s made up by the author, it’s classified under the main category of fiction.

Within those two genres, there are many different subcategories which can be referred to as subgenres, common genres, or other genres.

Here is an overview of many of the genres commonly found in children’s literature, from baby books to young adult novels. I’ve grouped them according to their similarities from a writer’s viewpoint rather than how a library, bookstore, or school might list them. And of course because writers are creative people who like to explore the familiar while creating innovative new types of literature, there are genres not listed here including new ones that might be hitting the market today. This list, however, will get you started with an overview.

Realistic Fiction

Historical Fiction

Literary Fiction

Christian Fiction

Novel in Verse

Mystery

Humor

Adventure

Romance

Fantasy

Science Fiction

Thriller

Paranormal

Dystopia

Comic and Graphic Novel

Short Story

Myth

Tall Tale

Folk Tale

Legend

Fable

Fairy Tale

Poetry

Contemporary Nonfiction

Historical Nonfiction

Narrative Nonfiction

Biography

Autobiography

Memoir

If you want to print out a list of these genres to add to your Writer’s Notebook, just visit my site, Writing According to Humphrey and Friends. Scroll down to “Genres and Subgenres” under Helpful and Essential Lists and click on it. You’ll get a free printable worksheet where you can write down more genres that you’re working on or that you learn about.

In upcoming posts here on my blog, we’ll take a look at some of these genres on this list and how they influence your plot.

February 27, 2013

Genre Influences Plot

A genre is a category, or a group, of similar types of literature. For example, mysteries are a genre, or group of stories that are similar in how they have some type of whodunit riddle to solve, a person who follows the trail of clues, with witnesses and alibis and red herrings, too!

Genre influences plot. If the plot is the series of events that propels your reader from the beginning of your manuscript to the end, then genre is the “address” for your plot. For example, if the setting of your story takes place in France, there will be French people walking down the streets. You might have your main character speak a word in French now and then such as “Oui,” (yes) or “Merci,” (thank you) or “Bonne nuit” (good night). Your characters might eat escargot when staying at a friend’s house for dinner, or go to the Eiffel Tower for a school field trip.

Likewise, if your plot is all about a fourth grade boy going on a journey to find his missing sister, the genre you choose to use will influence your plot. If you choose to write a science fiction story, your main character will use high-tech scientific gadgets such as rocket ships or gamma rays or photosynthesis within each of the events that moves your reader from the beginning to the ending of your manuscript. Or if you choose to write historical fiction, you main character will live during an actual era in history such as the American Revolution and ride in a carriage past the Liberty Bell on his search.

It’s important to become familiar with different genres used in children’s writing. Since genre is a category, you’ll find sections at your local bookstore where different genres are grouped. In your public library, different books are also grouped on different shelves in different parts of the library according to which genre they fall into. If your manuscript gets published as a children’s book, it will be labeled on the Internet, stocked in a bookstore, or shelved at a library according to its genre. And since genre influences plot, it’s good to learn the basics about various kinds of genres.

So grab your notebook and pen! We’re going to be studying genre in upcoming posts here on my blog so that when we get back to discussing plot, we’ll have a better understanding of how the genre you choose to use influences the plot in your story.

February 25, 2013

Plot Changes: An Overview

A story that uses a story arc has a beginning, a middle, and an ending. The beginning of the story is where the main character and the main story problem are introduced. Then the first change in the plot occurs. This change is so significant that it’s comparable to a bridge the main character walks across and then blows up behind him. The main character cannot go back and is forced to move forward into the middle of the story.

The middle of the story is where the main character comes face to face with the main story problem. At the very center of the middle, the second change in plot occurs. This change transitions from the first half of the middle into the second half of the middle. This change is so significant that it’s like another bridge. The main character crosses this bridge and then it blows up behind him. The main character cannot turn around or go back and is forced to move forward into the second half of the middle.

When the second half of the middle draws to a close, the third change occurs in the plot. Once again, this change is so significant that it’s like another bridge. The main character crosses this bridge and then it blows up behind him. The main character cannot go back and is forced to move forward into the ending of the story.

The ending of the story is where the main character solves the main story problem. The story wraps up and comes to a satisfying conclusion.

February 22, 2013

The Third Change

Every story has an ending. If you’re writing a story that uses a story arc, the ending is where the main story problem is solved. By learning how to transition successfully from the middle of your story to the ending, you can create a plot format that concludes with a high dose of satisfaction for your reader, leaving both children and adults alike filled with a sense of pleasure.

At the conclusion of the middle, the third change occurs in the main plot of your story. This change draws the middle to a close and introduces the ending of your story. Using A Sick Day for Amos McGee as our example, the third change occurs on page 23. The zoo animals arrive at Amos McGee’s house, much to the zookeeper’s delight.

All the scenes in the second half of the middle showed the zoo animals on their way to Amos McGee’s house. Then they arrived! This significant change marked the spot where the middle transitioned into the ending of the story.

The ending of the story concludes with all the different ways Amos McGee’s zoo friends cheer him up. The story draws to a close with Amos McGee’s announcement that he is feeling better, well enough to get out of bed and share a pot of tea. And finally, sigh of happiness, his friends read him a bedtime story and tuck him into bed. Amos McGee’s day has come to a very satisfying end.

February 20, 2013

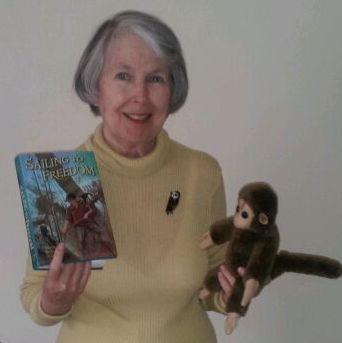

Author Interview: Martha Bennett Stiles

Meet Author Martha Bennett Stiles!

Websites:

Martha Bennett Stiles Home

Martha’s Books

Blog: Martha Bennett Stiles

Facebook: Martha Stiles

E-mail: mbsparis@msn.com

Bio:

I grew up in Virginia on the 7-mile wide James River estuary, around a bend from the location of my first book, One Among the Indians. I graduated from Smithfield Virginia’s high school two years early, which I do not recommend, then worked my way through college, beginning at William and Mary, which I loved, finishing at the University of Michigan, to which I owe even more. I majored in chemistry and worked for DuPont until I married Martin Stiles, a post doctoral fellow who became first, a UofM chemistry professor and editor of the Journal of the American Society, then a Bourbon County, KY Thoroughbred breeder. My MG, Sarah the Dragon Lady, and YA, Kate of Still Waters, were two of my rewards for the latter phase.

It was at my husband’s urging that I signed up for writing classes at UofM. It was his Guggenheim Fellowship that enabled me to write my third historical novel and most earnestly intended book, Darkness Over the Land, which is dedicated to our late son, John. Now a widow, I live in Lexington, Kentucky.

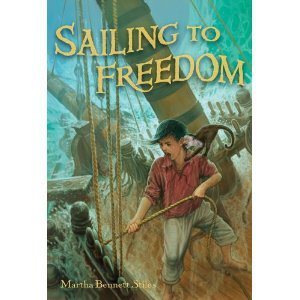

Featured Book:

Sailing to Freedom

by Martha Bennett Stiles

Henry Holt & Company, 2012

Twelve-year-old Ray’s in trouble from the moment he & his monkey, Allie, board The Newburyport Beauty. But when bounty hunters come looking for a runaway slave, it’s Ray & Allie who must save hideaway, crew, vessel, and all. Meanwhile, the runaway’s 11-year-old brother, Ogun, makes his desperate way from South Carolina to Canada on foot.

Interview:

Q: Do you ever base characters in your books on people you know or have known in your past?

A: A quick mental check of my books turns up no specific portraits. Here and there a character will behave in a way that vividly recalls something about someone, but by the next page or even paragraph, the two are otherwise unlike. The way Captain Ingle teaches Sailing to Freedom’s Ray to tie knots is taken straight from my impertinent younger sister Elizabeth Leal’s lesson to me on how to truss a chicken. In The Strange House at Newburyport, the first written of my books but the second published, the heroines’ Grandmother was originally my Great-aunt Martha Bennett, but my editor (Jean Vestal) was so dismayed by her effectiveness relative to her granddaughters’ that she persuaded me to shift that balance, one of the urgings for which I will always owe her.

Other matches are more elusive. Lonesome Road’s Lorena is based on a girl in the next older group at the Girl Scout camp I attended for two weeks–how she looked and sounded. I never exchanged words with her, but I vividly remember a skit she performed for everybody in which she played a hero climbing a tower. She ran round and round nothing, giving the illusion of an exhausting climb. I remember her voice and diction from her lament, which no one took seriously, that her parents didn’t love her, were going on a trip so she had to spend some more time in the camp.

In The Star in the Forest, my heroine’s sweet, sensible friend Brunehaut is based on my sweet, sensible schoolmate Spencer Haverty, who sat beside me on the school bus and listened to me with saintly patience. Spencer shows up again in Kate of Still Waters’ friend Hetty Anne Engle. Lonesome Road’s detective looks and sounds like a man who ran, successfully, I’m glad to say, for Ann Arbor, Michigan’s city council. I went to a Candidate’s Tea for him once, and I spoke to him once in the market, and that is my total exposure to him, as I never attended a council meeting. Island Magic’s grandfather was inspired by UofM’s Professor Roy Cowden, and my narrator is named for his grandson, but the character suffered a sea change after my sensible editor, Jonathan Lanman, pointed out that as my intended audience was David’s age, maybe I should give David some of the good lines.

Q: Describe the journey you�’ve taken as a writer to experience breakthrough to land a contract with a big publisher.

A: My first sale was a story about a duck who learns, of necessity, to ice skate: “Serena’s Surprise,” Humpty Dumpty’s Magazine, November l957 (later anthologized by Ginn Textbooks, who never sent me a copy but paid me as much as I had been paid by Humpty Dumpty). I read the original acceptance letter at the mailbox and did not run but bounded all the way to the front door. Acceptance was conditional on my cutting my manuscript in half. I did not argue.

Now a Published Author, I was able to acquire an agent, who sold my historical novel One Among the Indians to Dial Press. Dial was just beginning to publish for children, which increased their availability to beginners like me. The book appeared as my husband and I sailed for his Guggenheim year, and on our ship was a German publisher, who suggested that I submit my book to his firm. I signed their contract, but after my return to Michigan, my first letter from them was not the promised copy of said contract now signed by them, but the news that their firm was not going to produce any more children’s books.

While in Munich, we had been introduced to a writer who urged me to submit my book to her Swiss publisher, Schwabenverlag. I explained that Allein Unter Indianern was already bespoken. Apparently my German was rotten, because she submitted her own copy, and scarcely had the first firm written me their Dear John, than I got an offer from Schwabenverlag. It seems that Swiss and German boys have been fans of Native Americans ever since they began reading James Fenimore Cooper. During Jamestown’s celebration of her 400th year, Authors Guild-iUniverse reprinted One Among the Indians as a paperback, so it is again available, mirabile dictu.

Q: What is one word of advice you received as a writer that you would like to share with others?

A: Read

Q: Share one goal you have as a children�s writer and the steps you are taking to achieve it.

A: I would like my books to be honest and, without getting caught at it, helpful. Sarah the Dragon Lady, for instance, handles some things well that at her age I really muffed.

The steps I take to approach my goal are to keep at it and to keep at it.

Nancy I. Sanders's Blog

- Nancy I. Sanders's profile

- 76 followers