Nathan J. Winograd's Blog, page 3

March 13, 2021

This Week in Animal Rights (Mar. 8, 2021)

Dolly Mama is waiting at the Williamsburg, VA, shelter. In 2020, the shelter reported a 94% placement rate for dogs, 96% for cats, and 99% for rabbits and other small animals.

Dolly Mama is waiting at the Williamsburg, VA, shelter. In 2020, the shelter reported a 94% placement rate for dogs, 96% for cats, and 99% for rabbits and other small animals.Extremists on both ends of the spectrum — the NRA on the Right and, on the Left, critical race theorists — are keeping dogs on chains. 133 years ago this week, the animals lost a great friend: Henry Bergh, the founder of the nation’s first SPCA, died. For the first time, “scientists have developed a cancer drug without testing it on animals by using a chip that simulates the human body.” Legislation in Colorado calls upon animals to be killed based on an animal’s “mental and emotional” state, even when — as is the case more often than not — simply getting the animal out of the pound can resolve any “mental and emotional” concerns. Recent CDC guidance on COVID-19 pet care falls short. The number of communities placing over 95% and as high as 99% of the animals is increasing. And Best Friends is lying about Los Angeles having achieved No Kill.

In case you missed it:

SB 650, a bill to ban perpetual chaining of dogs, is pending before the Florida legislature. The bill had broad bipartisan support; at least it did until the National Rifle Association objected. They are not alone. Extremists on both ends of the spectrum — the NRA on the Right and, on the Left, critical race theorists — are keeping dogs on chains. 133 years ago this week, the animals lost a great friend. On March 12, 1888, Henry Bergh, the founder of the nation’s first SPCA, died. Although he is not a very well known figure, we and the animals owe him a great deal. Every humane society that stands up for animals; every animal protection group that gives voice to the voiceless; and the millions of animals who have been saved thanks to the efforts of activists and advocates, are a living legacy to his life. Bergh was one of the first Americans to begin weaving the ideals of animal protection into our jurisprudence, the American psyche, and the fabric of American life.For the first time, “scientists have developed a cancer drug without testing it on animals by using a chip that simulates the human body.”Legislation in Colorado calls upon animals to be killed based on an animal’s “mental and emotional” state, even when — as is the case more often than not — simply getting the animal out of the pound can resolve any “mental and emotional” concerns. This a real and immediate threat to shy and scared animals, as well as community (“feral”) cats and it is a very dangerous precedent to introduce in the animal control laws of our nation.The CDC has recently issued guidance on COVID-19 pet care. It’s a bit, well, bonkers and I say this as someone who always wears a mask outside, follows strict quarantine procedures, and is waiting for a vaccine I will get as soon as I am eligible.The number of communities placing over 95% and as high as 99% of the animals is increasing:

Northumberland County, VA, reported a 97% placement rate for dogs and 96% for cats.Montgomery County, VA, reported a 96% placement rate for dogs, 92% for cats, and 98% for rabbits and other small animals.The shelter that serves both James City County and Williamsburg, VA, reported a 94% placement rate for dogs, 96% for cats, and 99% for rabbits and other small animals.These shelters and the data nationally prove that animals are NOT dying in pounds because there are too many or too few homes or people don’t want the animals. They are dying because people in those pounds are killing them. Replace those people, implement the No Kill Equation, and we can be a No Kill nation today.

And finally, Best Friends is lying about Los Angeles having achieved No Kill. And we know L.A. has not achieved it because: 1. The cat placement rate was only 88%; 2. Even if it was 90% (and it wasn’t) it compares poorly with the communities placing 99% of cats now serving millions of Americans; 3. The city pound admittedly killed healthy cats all year; and, 4. It closed its doors for much of the year, turning away even injured animals, resulting in animals being abandoned. This much should go without saying: We don’t achieve No Kill by closing the doors to stray and injured animals. We don’t achieve it by killing healthy animals (as long as we keep that killing under 10%). We achieve No Kill by not killing them.

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.

March 12, 2021

Best Friends is lying about No Kill L.A.

This little cat was left in the parking lot of Los Angeles Animal Services when the person trying to surrender him was turned away because the pound closed its doors for much of the year. A rescuer trying to help the cat was told by “shelter” staff that she needed a permit to trap him, would not be given a permit, and was not allowed to even provide food or water on threat of prosecution. Other shy cats were not so “lucky” as the pound was under a court order to kill even healthy “feral” cats. And yet, Best Friends falsely claimed this week that despite all this, the city is No Kill.

This little cat was left in the parking lot of Los Angeles Animal Services when the person trying to surrender him was turned away because the pound closed its doors for much of the year. A rescuer trying to help the cat was told by “shelter” staff that she needed a permit to trap him, would not be given a permit, and was not allowed to even provide food or water on threat of prosecution. Other shy cats were not so “lucky” as the pound was under a court order to kill even healthy “feral” cats. And yet, Best Friends falsely claimed this week that despite all this, the city is No Kill.In 2012, Best Friends promised a No Kill Los Angeles by 2017. It didn’t happen and the five-year plan was extended to 10-years. If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. And if you still do not succeed, well, just go ahead and lie about it. That is what Best Friends has done with this week’s announcement by CEO Julie Castle that the City of Los Angeles achieved No Kill in 2020 with a 90% placement rate.

They did not.

And we know they did not because: 1. The cat placement rate was only 88%; 2. Even if it was 90% (and it wasn’t) it compares poorly with the communities placing 99% of cats now serving millions of Americans; 3. The city pound admittedly killed healthy cats all year; and, 4. It closed its doors for much of the year, turning away even injured animals, resulting in animals being abandoned (including the little cat pictured here).

This much should go without saying: We don’t achieve No Kill by closing the doors to stray and injured animals. We don’t achieve it by killing healthy animals (as long as we keep that killing under 10%). Here’s a shocker, we achieve No Kill by not killing them.

But Best Friends is not a group that lets facts stand in the way of a good fundraising story:

1. The 2020 placement rate for cats was 88%. That’s not a judgment call. It’s math.

2. Even if it was 90% — and it was not — statistics from the best performing shelters in the nation, serving millions of Americans, indicate that ending the killing of all but irremediably physically suffering animals entering a shelter results in a placement rate of 99%+. Best Friends wants to claim that you can kill 10 times as many and still be No Kill, legitimizing the killing of healthy and treatable animals, while betraying the very ethos at the heart of the term “No Kill.”

3. Los Angeles Animal Services (LAAS) killed healthy “feral” cats, the very opposite of No Kill. In fact, because of a 2009 court ruling, Los Angeles Animal Services has spent the last 11 years, including all 12 months of 2020, killing healthy “feral” cats. The City has long claimed that in order to stop killing these cats, it needed to conduct an environmental impact report, the City Council needed to approve it, and the Court then needed to accept it before it would lift the injunction prohibiting TNR. EIR completion and City Council vote did not occur until December 8, 2020, the last month of the year.

4. For much of the year, the “shelter” closed its doors, stopped taking in animals, including — according to a lawsuit — stray and injured animals. That resulted in cats simply being abandoned, including the little cat pictured here who was left in the parking lot of the pound when the person trying to surrender him was turned away. A rescuer trying to help the cat was told by “shelter” staff that she needed a permit to trap him, would not be given a permit, and was not allowed to even provide food or water on threat of prosecution, hardly a vision for No Kill.

Not surprisingly, intakes were down almost half (46%) from the year prior, which begs the question why the placement rate was not even higher given the low intake, combined with the massive demand for pets by the public during the extended lockdown.

Does achieving higher placement rates require closing one’s doors to injured animals? Leaving cats in parking lots with no food or water (and threatening to prosecute rescuers trying to help them)? Killing healthy “feral” cats? Or falsely pretending, as Julie Castle just did, that only animals who are irremediably suffering — those animals for whom killing really is “euthanasia” — are losing their lives? Absolutely not. That’s not what the No Kill movement is about. It is, in fact, its antithesis. And pretending otherwise only leaves animals at continued mortal risk.

If Best Friends and LAAS officials actually did the work to create a No Kill L.A. in earnest — something that should not be hard to do given its extremely low per capita intake rate and its relatively high per capita funding rate — they could actually be the heroes they now only pretend to be.

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.

March 11, 2021

The CDC dials it in for pets

The Centers for Disease Control has recently issued guidance on care of pet dogs and cats in the age of COVID-19 and it has led to a number of news articles about it. Unfortunately, that guidance is — I want to say — a bit bonkers, but “bonkers” isn’t a word I normally use in articles, preferring more sober language. It is, though. And I say this as someone who always wears a mask outside, follows strict quarantine procedures, and is waiting patiently (and some days not so patiently) for a vaccine I will get as soon as I am eligible. In other words, I am not someone who is anti-vax, anti-government, mask-politicizing, or prone to conspiracies. To the contrary, I look fondly back — to quote Miss Manners — at “the halcyon days when we naively thought that facts were immutable and universal.”

That said, the CDC has four recommendations:

1. Keep cats indoors when possible and do not let them roam freely outside.

The advice to isolate cats indoors comes, despite the CDC admitting that the very, very small number of cats who tested positive did so after prolonged contact with an infected person of the same household as the cat. So, presumably, going outside would not put them at risk; to the contrary even. Studies and epidemiological data, moreover, have also shown they get only mild symptoms, can’t spread it from contact with their skin, fur, or hair, do not readily pass it to each other, and can’t infect people at all.

2. Pets or other animals should not be allowed to roam freely around the facility, and cats should be kept indoors.

It is not clear what “facility” they are referring to since this is advice to the public, is entitled “If You Have Pets,” and, as to cats being kept indoors, well, they already said that and it was bad advice to begin with. Saying it twice doesn’t make it more compelling. It is, in fact, the functional equivalent of multiple exclamation points: methinks thou does protest too much.

3. Avoid public places where a large number of people gather.

It is not clear how this relates to animals, especially since it tracks language in their early advice for people. Like the “facility” comment above, it appears someone at CDC “cut and paste” this from elsewhere and did not go back and edit. Cats are hardly likely to congregate “where a large number of people gather,” and dogs are not readily-infected, the few that did get infected did so after prolonged contact with an infected person in their own household, and they are dead-end hosts, meaning they cannot transmit it to anyone, including other dogs.

4. Do not put a mask on pets. Masks could harm your pet.

I have yet to see a single mask on a single pet, so it is not clear there is an audience for this and I live in the San Francisco Bay Area. If pet mask-wearing was a thing, it would be a thing here. And it isn’t. Moreover, I can’t imagine a cat tolerating anyone trying to put a mask on them. As my old Poli Sci advisor used to quip, this a solution in search of a problem.

The advice comes one year after the World Health Organization declared a pandemic, three vaccines are in U.S. circulation, and the pandemic begins to wind down. I am going to go out on a limb here and say that pet COVID-19 tips are not a high priority item for the CDC, given how late in the day it comes, given how poorly they were written, and how poor the advice. I get it. There have only been roughly 100 U.S. cases among dogs and cats, compared to 29.2 million people, of whom 529,000 have died. They dialed this one in. But anything worth doing is worth doing well, especially on an issue that is immensely important to most of us.

Thankfully, other (inter-)governmental organizations around the world — including at least one of which the CDC ironically links to — do have long-standing and sober advice:

1. “There is no evidence that companion animals are playing an epidemiological role in the spread of human infections of SARS-CoV-2” (the virus that causes COVID-19) so we should not do anything to compromise their welfare.

2. If you have COVID-19 and have prolonged contact with your pets, since this is the primary mechanism of transmission for them (although still rare), wear a mask and “maintain good hygiene practices” out of an abundance of caution.

Noted.

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.

March 10, 2021

Colorado bill would promote killing of animals for “mental and emotional” state

Even when — as is the case more often than not — simply getting the animal out of the pound can resolve any concerns.

Mr. Pickles — young, healthy, friendly, already neutered — should have had everything going for him; his stay at an American shelter in one of the richest and most cosmopolitan communities in the world a temporary waystation to a better life. Unfortunately, he entered a pound that did not revere life, did not hold staff accountable to results, and found killing easier than doing what was necessary to stop it. Within a few short days, and without ever being made available for adoption, he drew his last breath. Staff at the pound that practices “socially conscious animal sheltering” poisoned him with an overdose of barbiturates.

Mr. Pickles — young, healthy, friendly, already neutered — should have had everything going for him; his stay at an American shelter in one of the richest and most cosmopolitan communities in the world a temporary waystation to a better life. Unfortunately, he entered a pound that did not revere life, did not hold staff accountable to results, and found killing easier than doing what was necessary to stop it. Within a few short days, and without ever being made available for adoption, he drew his last breath. Staff at the pound that practices “socially conscious animal sheltering” poisoned him with an overdose of barbiturates.Last year, the Denver Dumb Friends League, the flagship of the regressive sheltering establishment in Colorado, lied to the media, the public, and legislators by claiming that there isn’t a single pound in the state that kills animals: “There are no kill shelters in Colorado.” Worse, the organization and its allies introduced legislation to legitimize the status quo. The bill went by the Orwellian name the “Colorado Socially Conscious Sheltering Act,” which is a euphemism for a poorly run pound that kills animals in the face of common-sense, cost-effective, readily-available alternatives it simply refuses to implement. Thankfully, and rightly, the bill died in committee.

Tragically, it has been revived this year.

The newly introduced bill legitimizes the killing of animals if a shelter says it is out of room, does not require foster care, community cat sterilization, offsite adoptions or any number of other programs that replace killing with alternatives, and defines treatable animals very narrowly. Worst of all, it calls upon animals to be killed based on an animal’s “mental and emotional” state. Not only is there no objective definition of what constitutes mental suffering and no standards to how it will be applied, it legitimizes the killing of animals based on the animals’ perceived state of mind, giving people unqualified to make such a determination discretion to kill animals based on unenforceable, unknowable, and completely subjective criteria, even when — as is the case more often than not — simply getting the animal out of the pound can resolve any “mental and emotional” concerns. This a real and immediate threat to shy and scared animals, as well as community (“feral”) cats and it is a very dangerous precedent to introduce in the animal control laws of our nation.

Because it excuses killing, however, “socially conscious animal sheltering” is, not surprisingly, embraced by some of the most regressive agencies in the state and country. This includes pounds — like the Los Angeles County Department of Animal Care & Control (LACDACC) — that allow animals to starve, refuse to embrace programs that replace killing like community cat sterilization, and do not hold even abusive employees accountable.

Take Mr. Pickles, a little cat surrendered by his family to the LACDACC. Although initially scared, Mr. Pickles turned out to be very sweet, rubbing up against the bars of his cage when volunteers or staff walked by and calling out to them with a soft meow. He was so pliable, in fact, a volunteer put Mr. Potato Head glasses on him, caressed his orange face, and snapped his photo to show others how cute he was.

Mr. Pickles — young, healthy, friendly, already neutered — should have had everything going for him; his stay at an American shelter in one of the richest and most cosmopolitan communities in the world a temporary waystation to a better life. Unfortunately, he entered a pound that did not revere life, did not hold staff accountable to results, and found killing easier than doing what was necessary to stop it. Within a few short days, and without ever being made available for adoption, he drew his last breath. Staff at the pound poisoned him with an overdose of barbiturates.

Embrace of “socially conscious animal sheltering” also includes groups like PETA, which has a history of stealing animals to kill, instructing its staff to lie to people in order to acquire and kill their animals, undercounting the amount of sodium pentobarbital it uses in order to kills animals “off book,” defending poorly performing, even abusive, pounds, rounding up to kill healthy cats and kittens, demonizing cats to fight progressive programs like community cat sterilization as an alternative to that killing, and putting to death as many as 99% of the animals it impounds, while only adopting out 1%.

If you live in Colorado, now is the time to make your voice heard. Please contact your state Representative and urge a No vote on HB 21-1160.

Also contact Representative Monica Duran, the bill’s sponsor, and politely ask her to withdraw it: monica.duran.house@gmail.com. Legislators rely on lobbyists and constituents and rarely have any real working knowledge about their own bills. This appears to be one of those cases.

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.

March 8, 2021

Clowns to the Left of me, Jokers to the Right

Extremists on both ends of the spectrum — the NRA on the Right and, on the Left, critical race theorists — are keeping dogs on chains.

“And homeless near a thousand homes I stood” — William Wordsworth

SB 650, a bill to ban perpetual chaining of dogs, is pending before the Florida legislature. The bill had broad bipartisan support; at least it did until the National Rifle Association objected. In an absurd claim, a lobbyist for the organization called even extended chaining “humane.” It is anything but.

For dogs, as for people, the absence of human attention and affection is tragic. Besides suffering from isolation, a chained dog suffers the added frustration of being unable to act out even the most basic of dog behaviors. The small circle in which he can move about becomes hard–packed with dirt which carries the stench of his waste (even if the fecal matter is routinely cleared away). The odor draws flies and serves as a breeding ground for parasites, which can infect him. After a few weeks, he will begin to show temperament disorders. Over time, he is likely to become aggressive. If he stays chained for months or years, he may even become mentally ill.

Americans of all walks of life and political stripes love their dogs and know that denying them basic liberties by chaining them to a stake is wrong. The NRA — which claims to advocate for freedom — should, too. But the NRA is not alone in their opposition to criminalizing animal abuse. In deference to identity politics, an increasing number of academics are likewise advocating that we turn a blind eye to chaining.

In a recent book, University of California Riverside Professor Katja Guenther argues that treating animals as family and showing them affection are “white” values, while treating animals “as resources, whether protective (as in guarding) or financial (as in breeding or possibly fighting)” are part of the culture of people of color. She claims that rescuers who want dogs to be adopted to “those who will treat their dog as a family member” and will “care for their dog” are using dogs “as instruments for reproducing whiteness.”

Tufts Professor (Emeritus) Andrew Rowan argues that people of color have “culturally specific” “folk knowledge” that guides their “indigenous” human-animal relations and that shelter workers should lower their standards in deference to these “indigenous” relations, even when doing so is “at odds with the humane society’s own core beliefs about how animals should be cared for.”

Likewise, the University of Denver’s Kevin Morris is calling for eliminating the enforcement of animal protection laws that ban continuous chaining of dogs in backyards because “regulations for adequate care of animals” “criminalize individuals experiencing poverty and people of color who have pets.”

So much progress has been subverted by fringe politics on both ends of the spectrum. It doesn’t matter if you disdain the NRA or are a lifetime member; disdain identity politics or advocate for them, dogs deserve so much better. Dogs who are perpetually chained have few friends, literally and figuratively. We must be. And we should not allow hard-hearted ideologues to stop us from protecting them.

Dogs offer people undying loyalty and unconditional love. In return, they ask for nothing more than a sense of belonging. To banish a dog permanently to a chain is a betrayal of what should be a loving pact. And that is no way to treat “man’s best friend.”

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.

March 5, 2021

This Week in Animal Rights (Mar. 1, 2020)

“The Utah Senate voted unanimously… in favor of a bill that would end gas chamber euthanasia for animals in the state… Utah is one of only four states where some animal shelters are still using gas chamber[s].” The bill now goes before the House.

“The Utah Senate voted unanimously… in favor of a bill that would end gas chamber euthanasia for animals in the state… Utah is one of only four states where some animal shelters are still using gas chamber[s].” The bill now goes before the House.“The Utah Senate voted unanimously… in favor of a bill that would end gas chamber euthanasia for animals in the state…” Illinois legislation would make it illegal for pet stores to sell commercially-bred puppies and kittens. Dogs have turned humanity into slaves. A new report in USA Today says that, “Since Seresto flea and tick collars were introduced in 2012, the EPA has received incident reports of at least 1,698 related pet deaths.” A growing number of academics are trying to keep people segregated by color on the proverbial bus and throw animals under it. The number of communities placing over 95% and as high as 99% of the animals is increasing. And Newsweek reported that PETA has killed “tens of thousands of animals.” Unfortunately, they also bought into one of PETA’s two big lies as to why they kill so many.

In case you missed it:

– “The Utah Senate voted unanimously… in favor of a bill that would end gas chamber euthanasia for animals in the state… Utah is one of only four states where some animal shelters are still using gas chamber[s].” The bill now goes before the House.

– Illinois legislation would make it illegal for pet stores to sell commercially-bred puppies and kittens. If they want to offer animals, House Bill 3646 would require that “the dog or cat is obtained from an animal control facility or animal shelter.”

– Dogs have turned humanity into slaves.

– A new report in USA Today says that, “Since Seresto flea and tick collars were introduced in 2012, the EPA has received incident reports of at least 1,698 related pet deaths. Overall, through June 2020, the agency has received more than 75,000 incident reports related to the collars…”

– A growing number of academics are trying to keep people segregated by color on the proverbial bus and throw animals under it. We shouldn’t confuse racist tropes and cruel policies with the cause of animal protection (or human dignity).

The number of communities placing over 95% and as high as 99% of the animals is increasing:

– Louisa County, VA, reported a 96% placement rate for dogs, 95% for cats, and 100% for bunnies and other small animals.

– Colonial Heights, VA, reported a 97% placement rate for dogs, 96% for cats, and almost all of the bunnies and other small animals.

– Appomattox County, VA, reported a 98% placement rate for dogs and 93% for cats.

These shelters and the data nationally prove that animals are NOT dying in pounds because there are too many or too few homes or people don’t want the animals. They are dying because people in those pounds are killing them. Replace those people, implement the No Kill Equation, and we can be a No Kill nation today.

And finally, Newsweek has a recurring feature they call “Fact Check” in which they evaluate various claims circulating on social media, ostensibly to determine whether those claims are true. The magazine recently evaluated the claim that PETA kills thousands of animals every year. There is no denying that PETA has killed over 40,000 animals. Those records come from PETA itself which it is required to report to the Virginia Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services. Not surprisingly, Newsweek determined that PETA has in fact killed “tens of thousands of animals.” Unfortunately, the person who they assigned to evaluate it was not completely up to the task. A recent college graduate — who describes herself as still “finding my voice” — the author excused that killing — labeling it as “Mostly True” instead of just “True” — because she bought into one of PETA’s two big lies as to why they kill so many.

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.

March 4, 2021

Newsweek: PETA has killed “tens of thousands of animals”

Unfortunately, the magazine accepted their excuse, overlooking the real reasons why

One of PETA’s 42,573 known victims.

One of PETA’s 42,573 known victims.Newsweek has a recurring feature they call “Fact Check” in which they evaluate various claims circulating on social media, ostensibly to determine whether those claims are true. The magazine recently evaluated the claim that PETA kills thousands of animals every year.

There is no denying that PETA has killed over 40,000 animals. Those records come from PETA itself which it is required to report to the Virginia Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services. Not surprisingly, Newsweek determined that PETA has in fact killed “tens of thousands of animals.”

Unfortunately, the person who they assigned to evaluate it was not completely up to the task. A recent college graduate — who describes herself as still “finding my voice” — the author excused that killing — labeling it as “Mostly True” instead of just “True” — because she bought into one of PETA’s two big lies as to why they kill so many. Quoting PETA itself, the author claimed that the killing “is to be expected with its open-door policy of taking in many animals no one else would accept.” (The other big lie is that all the animals PETA kills are suffering.)

First and foremost, the excuse ignores the hundreds of municipal and contracted-shelters across the country that also have an “open-door policy” but do not kill. Millions of Americans now live in communities served by municipal shelters that are finding homes for over 95% and upwards of 99% of animals, returning the term “euthanasia” to its dictionary definition: an act of mercy for “hopelessly sick or injured individuals.” These communities are large and small, urban and rural, red and blue, affluent and impoverished, homogenous and diverse. And they are achieving that success on a fraction of PETA’s budget.

In 2020, by contrast, PETA put to death 1,119 out of 1,542 cats. That’s a kill rate of over seven out of 10 cats. Another 407 went to pounds that also kill animals. Historically, many of the kittens and cats PETA has taken to those pounds have been killed, often within minutes, despite being young (as young as six weeks old) and healthy.

If those cats and kittens were killed or displaced others who were killed, that puts the overall cat death rate as high as 99%. They only adopted out 16 cats, an adoption rate of 1% despite millions of “animal loving” supporters, a staff of hundreds, and revenues of $66,277,867. While dogs fared a little better, 600 out of 1,052 were put to death. Less than 2% were adopted out. And PETA staff also killed 83% of other animal companions: 40 out of 48.

To date, PETA has killed 42,573 dogs and cats and sent thousands more to be killed at local pounds, that we know of. The number may be many times higher. According to a former PETA employee whose job it was to acquire animals to kill:

I was told regularly to not enter animals into the log, or to euthanize off-site in order to prevent animals from even entering the building. I was told regularly to greatly overestimate the weight of animals whose euthanasia we recorded, in order to account for what would have otherwise been missing ‘blue juice’ (the chemical used to euthanize); because that allowed us to euthanize animals off the books.

Second, PETA does not even try to find homes for many animals, as evidenced by a state inspection report showing PETA kills 90% of animals within 24 hours without doing so.

There’s more. Newsweek also ignored that:

PETA founder Ingrid Newkirk wrote an OpEd which appeared in newspapers across the country admitting PETA supports a policy that all “pit bulls” should be killed in all “shelters” in America.

PETA employees were arrested and put on trial for rounding up and killing animals in the back of a van after promising to find them homes.

Other PETA representatives were arrested after they stole Maya, a “happy and healthy” dog, from her home when her family was out and illegally killed her. (Maya’s family’s sued PETA and after PETA lost a motion where they claimed that the dog was worthless, settled for $49,000.)

PETA employees were told to lie to people by promising they would find homes in order to get them to surrender animals, but the animals were immediately killed instead.

PETA headquarters has a “terrifying” culture of killing.

PETA advocates for the round up and killing of healthy, sterilized community cats.

PETA rounds up to kill or have killed healthy kittens. (Here are more records showing PETA rounds up to kill cats and kittens and here are even more.)

PETA tells public officials not to foster animals and not to work with rescue groups.

The mass killing of pit bulls, the round up and killing of healthy cats and kittens, the stealing and killing of animals who already have homes, the lying to people by promising homes only to kill the animals right away (including in the back of a van), and the call for others to do the same has nothing to do with their “open admission” policy and it is not because the animals are “suffering.” And of course, PETA is not a “shelter” in any commonsense meaning of the word and has no contract to run one. It is not obligated to take in animals and it certainly is not required to kill them. It chooses to do so. The question, of course, is Why?

PETA employees say it is the result of the deeply perverse version of animal activism promoted by PETA founder and President, Ingrid Newkirk. They explain how employees are made to watch “heart wrenching” films about animal abuse to instill into them the belief that people are incapable of caring for animals and that PETA is doing what is best for animals by killing them. PETA also claims that animals cannot live without human care, which is why they round up animals living outdoors in order to put them to death. The animals are, in short, damned either way and thus killing them is a “gift.”

How do we know? In addition to the evidence above, Why PETA Kills, my book that covers this very topic, is based on exhaustive research, including records acquired from civil and criminal court cases, documents received under the Public Records Act, testimony by PETA staff members, and confidential informants.

Of course, all this information was readily available to the young reporter and her editors at Newsweek. Exposes have been published in various publications including the Atlantic, the New York Times, the Boston Globe, the Huffington Post, CNN, various other publications around the country, and, of course, my own articles and book. A simple Google search would have uncovered them, which makes the cub reporter’s conclusion all the more disappointing.

And while she might be excused for her profound failure as she admits she is still “finding her voice,” that she is a fact checker and did not fact check and, more importantly, that there are life and death consequences to her failure, would mitigate against doing so. More importantly, that doesn’t excuse Newsweek. The magazine was founded in 1933. If it still hasn’t found its voice after almost 90 years, I doubt it ever will.

Why PETA Kills is available for FREE download today and tomorrow from Amazon. (Please note: You don’t need a Kindle or Kindle Unlimited to read it if you click below Kindle Unlimited where it says “$0.00 to buy”.)

It is the book PETA does not want you to read. They sued to intimidate me and my sources into silence; a lawsuit two national journalism organizations called “alarming.” Despite PETA spending tens of thousands of dollars hiring one of the most expensive law firms in the country, however, I won.

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.

March 2, 2021

The Racism of Low Expectations (and Its Deadly Consequences for Animals)

Norman Lear — who is white — was once asked what made him think he could create “The Jeffersons,” a television show about a black family. He responded that his shared humanity allowed him to. He loved his family; they loved their families. He wanted health, safety, happiness, prosperity, comfort, and dignity; they wanted those things, too. “That is my belief,” he said. “We are just versions of each other.”

The exchange highlights the two fundamentally different ways to understand the importance of race. Race can be regarded as a morally meaningless distinction. That doesn’t mean ignoring inequality; to the contrary. It means rooting it out to build a colorblind society. This is how people like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. viewed race and, as I have said before, is the approach of classical liberalism, was the backbone of the civil rights movement for much of its history and has been at the heart of much of its greatest successes. It is the approach I support and — when advocating for the expansion of rights to non-humans — embrace, believing it to be an essential and tested means by which we can win animals greater protections.

But race can be regarded as a morally important distinction. This means working to create a segmented world where people are treated differently because of their skin color: whether on television, the workplace, politics, or even human-animal relations. This is the illiberal approach, which I reject. It is, however, how adherents of “critical race theory” think the world is and should be.

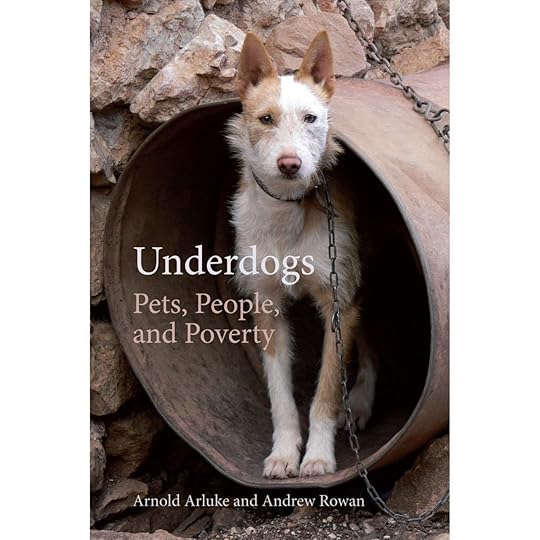

In Underdogs, Andrew Rowan and Arnold Arluke start with the premise that people of color are fundamentally different to whites and for that reason, argue that the animal protection movement should develop “ethnoracial cultural sensitivity” when it comes to judging how people of color treat their animal companions. Rowan and Arluke claim that black people have “culturally specific” “folk knowledge” that guides their “indigenous” human-animal relations. And they conclude that shelter workers should lower their standards in deference to these “indigenous” relations, even when doing so is “at odds with the humane society’s own core beliefs about how animals should be cared for.” They even go so far as to argue that shelters should turn a blind-eye to dogfighting.

Similarly, Katja Guenther argues in The Lives and Deaths of Shelter Animals that treating animals as family, showing them affection and providing them medical care are white values; in contrast to treating animals “as resources, whether protective (as in guarding) or financial (as in breeding or possibly fighting)” which she inaccurately claims is inherent to black or latino culture. She further argues that rescuers who want dogs to be adopted to “those who will treat their dog as a family member” and will “care for their dog at a high level for the duration of the dog’s life” are using dogs “as instruments for reproducing whiteness.”

This argument has been embraced, in part, by Kevin Morris and his team at the University of Denver Institute for Human-Animal Connection. In a recent paper, they call for “removing adoption requirements,” which they view as part of “the White dominant culture.” Like Guenther, Morris et al. ignore that rescuers and shelters have a moral and institutional obligation to the vulnerable animals they serve to ensure those animals are not placed in harm’s way; which can and should be done using standards that don’t focus on a potential adopter’s skin color or size of their bank account, but on their ability to provide for an animal’s physical and mental health. Ignoring this obvious point, the authors of that paper, as did Guenther before them, suggest that rescuers and shelters are obligated to place animals into knowingly unstable situations (which they incorrectly equate with skin color) or engage in what they deem to be racist behavior. Those tasked with caring for animals are damned either way.

Morris also calls for reducing, and in some cases eliminating, enforcement of laws aimed at preventing animal mistreatment, by arguing that such laws, including laws meant to ban continuous chaining of dogs in backyards and “regulations for adequate care of animals” to prevent abuse and neglect, “criminalize individuals experiencing poverty and people of color who have pets” and are “largely unobtainable for anyone in the US other than white, middle and upper-class individuals.” Like Rowan and Arluke, they call for cruelty officers to engage with “marginalized populations in a culturally competent manner” and call on municipal animal shelters and other agencies to embrace a model for enforcement that “emphasizes person-centered approaches…”

They have it backward. Some ways of relating to animals are better than others. Determining which does not start with the skin color of the person the animal is connected to, but objective norms rooted in the animal’s biology and Enlightenment values, including the unalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Feeding a dog daily is better than feeding a dog two times per week; letting a dog sleep in the house is better than chaining or keeping the dog outside 24 hours a day, seven days a week; providing professional veterinary care is better than untested “cultural” remedies; and treating dogs tenderly is better than fighting a dog to see if he can kill the other; all examples cited by either Morris, Rowan, Arluke, or Guenther. These are not white values; they are ways of relating to animals that increase the well-being of dogs and cats, and therefore, should be afforded to all of them, irrespective of the ethnicity, gender, race, or class of the human with whom they live. In other words, the animal protection movement must embrace an animal-centered approach. Arguing otherwise isn’t animal advocacy; it is its antithesis.

Second, as used by critical race theorists, cruelty is confused with “culture.” As such, “culturally competent” is a euphemism for creating a privileged class of animal abuser by subordinating the rights of animals to the interests of those who harm them, undermining the central tenet of the animal protection movement and leaving animals in danger. That is something we should never do.

To their credit, Morris et al., correctly argue that punitive approaches are often counterproductive, such as in enforcing licensing laws, pet limit laws, leash laws, and similar animal control ordinances that tend to be poor proxies for animal protection and often are not about protection at all, an argument I made over a decade ago in my 2008 book Redemption. But anti-tethering laws and other neglect statutes do protect animals. And they do so by setting out minimum standards of care and proscribing conduct that falls below it. They criminalize animal mistreatment, not poverty as Morris claims, and contrary to his claims, they are hardly mutually exclusive with dogs and cats in black households. Any arguments to the contrary not only throw the baby out with the bathwater, they bear little resemblance to how people of color feel about or treat animals.

There are, of course, more effective or less effective ways to help animals kept in compromised circumstances and Morris is likewise correct that there are times that education and subsidized services will achieve the desired outcome better than citations, which I have also argued elsewhere. Aside from dog fighting and other abuse which should always lead to rescue/seizure, arrest, and prosecution (something Morris likewise argues, but Rowan, Arluke, and Guenther do not), we want the other behaviors to change, through education and pro bono services if possible or need be (as in cases of extreme poverty), but prosecution if necessary because the welfare of animals is of consequence. But this has nothing to do with skin color, “cultural competence,” eliminating adoption standards, or deregulating care standards as Morris recommends. Once again, doing so is throwing the baby out with the bathwater. It also puts animals at increased risk.

In 1974, at a time when “shelters” were killing over 15 million animals a year — roughly 90% of all intakes — then-American Humane Association President Rutherford Phillips gave a speech to his fellow leaders in the animal welfare movement arguing against treating people equally. Calling for stringent adoption standards, he said that only certain kinds of potential adopters were worthy of having pets. To prove his point, he claimed — in a speech reeking with racial overtones — that past adoptions in “ghetto areas” were a failure, and that these dogs were now doing little more than “attacking children in schoolyards.”

Since then, the number of animals killed has declined by 90%, with millions of Americans now living in communities served by municipal shelters that are finding homes for upwards of 99% of animals. These communities are large and small, urban and rural, red and blue, affluent and impoverished, homogenous and racially diverse. But almost half a century later, the ghost of Rutherford Phillips is rearing its ugly head once again.

While some critical race theorists are arguing for the elimination of adoption and responsibility standards and others are excusing perpetual chaining, backyard breeding, and even dogfighting, they are basing it on the same fetid premise: that even reasonable standards are too high for black people, because they are supposedly different, lesser, incapable of providing high levels of care, love, and attention. It is the other side of the same ugly coin.

In the wake of the protests over the death of George Floyd, organizations across the country have looked for ways to express solidarity with the cause of civil rights and animal welfare groups are no exception. But we should not confuse the racist tropes and cruel policies peddled by some with the cause of animal protection (or human dignity). They not only threaten to undermine decades of past progress, they threaten future progress, too. Their combined advocacy for subordinating the welfare of animals to the interests of the people they are connected to is incompatible with advancing animal rights.

As philosopher David Pearce writes, “Over the last century, a welfare state for humans was introduced in Western European societies so that the most vulnerable members of our own species wouldn’t suffer avoidable hardship.” “The problem,” as he notes, “is not just that existing welfare provision is inadequate: it’s also arbitrarily species-specific. In common with the plight of vulnerable humans before its introduction, the welfare of vulnerable non-human animals depends mostly on private charity. No universal guarantees of non-human well-being exist.” They should and they invariably will.

How soon that day comes will be determined by how well the animal protection movement stays focused on the means by which we have already achieved so much, and whether or not we allow our attention and energies to be fruitlessly diverted by academics trying to purchase professional notoriety peddling a faddish, but irrational, critical race theory, at the cost of the welfare, rights, and even the lives of animals.

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.

February 26, 2021

This Week in Animal Rights (Feb. 22, 2021)

Pennsylvania’s bill to ban the retail sale of commercially-bred puppies, kittens, and rabbits “is called ‘Victoria’s Law,’ named for a German shepherd [who…] gave birth to more than 150 puppies during her time at a mill… Victoria had a genetic disease, which eventually left her paralyzed and in need of being humanely euthanized, and — unbeknownst to unsuspecting consumers — would have passed that disease to her offspring.”

Pennsylvania’s bill to ban the retail sale of commercially-bred puppies, kittens, and rabbits “is called ‘Victoria’s Law,’ named for a German shepherd [who…] gave birth to more than 150 puppies during her time at a mill… Victoria had a genetic disease, which eventually left her paralyzed and in need of being humanely euthanized, and — unbeknownst to unsuspecting consumers — would have passed that disease to her offspring.”Legislation pending in Nevada would make it illegal for insurance companies to discriminate against dogs based on alleged “breed.” After 311 days in the shelter, Kane has a loving home of his own. Legislation introduced in Pennsylvania would make it illegal for pet stores to sell commercially-bred puppies, kittens, and rabbits. A lawsuit alleges that the director of the Franklin County, OH, pound retaliated against rescuers, putting dogs at risk. Local “shelters” and national groups are attempting to pass laws allowing pounds to kill animals for “mental suffering.” Some “shelters” are falsely claiming they can still kill 10% of animals and be No Kill. The number of communities placing over 95% and as high as 99% of the animals is increasing. And more academics are seeking to purchase professional notoriety by peddling a faddish but harmful “critical race theory” at the cost of animal rights, claiming that skin color is a reason to condone differential levels of care.

In case you missed it:

– Legislation pending in Nevada would make it illegal for insurance companies to discriminate against dogs based on alleged “breed.”

– After 311 days in the shelter, Kane has a loving home of his own. What do we owe the animals who arrive in our shelters looking for a second chance? We owe them safe harbor: no matter how many there are and no matter how long it takes to find them a home.

– Legislation introduced in Pennsylvania would make it illegal for pet stores to sell commercially-bred puppies, kittens, and rabbits.

– A lawsuit alleges that the director of the Franklin County, OH, pound retaliated against rescuers, putting dogs at risk. The Complaint pending in federal court alleges infringement of First Amendment, retaliation, fraud, tortious interference with contract, destruction of public records, and other claims.

– Local “shelters” and national groups are attempting to pass laws allowing pounds to kill animals for “mental suffering.”

– Some “shelters” are falsely claiming they can still kill 10% of animals and be No Kill. A commitment to the well-being of animals demands that today’s performance no longer be measured by yesterday’s standards.

Indeed, the number of communities placing over 95% and as high as 99% of the animals is increasing:

– Fluvanna County, VA, reported a 95% placement rate for dogs and 95% for cats.

These shelters and the data nationally prove that animals are NOT dying in pounds because there are too many or too few homes or people don’t want the animals. They are dying because people in those pounds are killing them. Replace those people, implement the No Kill Equation, and we can be a No Kill nation today.

And finally, more academics are seeking to purchase professional notoriety by peddling a faddish but harmful “critical race theory” at the cost of animal rights, claiming that skin color is a reason to condone differential levels of care. Stripping away the racist distractions, the evidence presented not surprisingly found that people of color have the same views about animals as everyone else.

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.

February 23, 2021

Follow the (Lack of) Money

A Review of Underdogs

Earlier this month, over the course of six Facebook posts, we had a discussion about race and its (lack of) impact on “shelter” killing. This discussion coincided with an article I wrote for an online magazine in response to the publication of The Lives and Deaths of Shelter Animals, a book by Katja Guenther. The book (incorrectly) claimed that dogs are being killed because of white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalist exploitation.

I argued that a lack of basic sheltering programs — not lack of diversity — explained shelter killing. I argued that her premise threatened to derail No Kill progress by diverting the attention of the animal protection movement away from proven strategies towards social theories about race that are not only wrong, but bear little relevance to shelter killing. And I rejected the author’s depiction of minorities as exploitative caretakers as factually inaccurate and racist.

You can review that six-part discussion here.

You can read my analysis in its entirety here.

You can also read my (streamlined) published article here.

Now, a new book argues that race explains treatment of animals outside the shelter, too. In Underdogs, Andrew Rowan and Arnold Arluke claim that we need to develop “ethnoracial cultural sensitivity” when it comes to judging how poor people of color treat their animal companions. Rowan and Arluke claim that they have “culturally specific” “folk knowledge” that underscores their “indigenous” human-animal relations. And they argue that shelter workers should lower their standards in deference to this folk knowledge, even when doing so is “at odds with the humane society’s own core beliefs about how animals should be cared for,” such as agreeing to vaccinate the dogs of dogfighters (rather than rescuing the dogs and having the perpetrators arrested and prosecuted). Doing so is necessary, they argue, because medical care, affection, and treating animals as family members are “middle class” and “White” values, rather than objectively better ways because they reduce suffering and maximize happiness.

Like Guenther before them, Rowan and Arluke are confusing cruelty with “culture.” Like Guenther before them, they are making unfounded claims that infantilize people of color. And like Guenther, they embrace these conclusions, despite evidence given in their book that clearly points to the contrary. As they themselves conclude, “When cost and transport barriers are removed, low-income black and Hispanic pet owners behave no differently than do white owners…” And yet, they argue that somehow (poor) Black people are fundamentally different from (middle class) White people with respect to animal care. Once again, these conclusions threaten to derail progress for animals by inaccurately portraying animal protection as a tool of racial oppression.

There are right and wrong ways of relating to animals

Rowan and Arluke, for example, note that, “Dogfighting is strongly opposed by the shelter because dogs are tortured, are disposed of when no longer good fighters, suffer from wounds that go untreated, [and] are bred to be used as bait…” They also note that, “Dogfighters who breed dogs are not interested in sterilizing their puppies.” Given the impasse, the authors wrongly suggest that the former should compromise, rather than the latter be prosecuted. Specifically, “As [shelter] workers try to transcend their objection to these practices by focusing on the bigger picture of promoting animal welfare, they develop strategies to work with… dogfighters so they vaccinate and sterilize at least some of their animals.” By this tortured logic, Rowan and Arluke seem to suggest that ensuring that dogs destined to be ripped to shreds be vaccinated is a greater priority that ensuring that animal cruelty laws be enforced so that those dogs do not become victims of dogfighting.

According to the authors, not only should we look the other way at intentional harm to animals, but we should likewise be willing to suspend disbelief, such as equating after-the-fact rationalizations for neglect or cruelty like not regularly feeding an animal with race and culture. Rowan and Arluke claim, for example, that some Black people, “believe that the best way to stop a chained dog from knocking over its food bowl is not to feed it.”

Some ways of relating to animals are better than others. Determining which does not start with the skin color of the person the animal is connected to, but objective norms rooted in the animal’s biology and Enlightenment values, including the unalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Feeding a dog daily is better than feeding a dog two times per week. Letting a dog sleep in the house is better than chaining the dog outside 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Providing professional veterinary care is better than untested “folk” remedies. And treating dogs tenderly is better than fighting a dog to see if he can kill the other. These are not “middle class” behaviors and they are certainly not “White” values; they are ways of relating to animals that objectively increase the well-being of dogs and cats, and therefore, should be afforded to all of them, irrespective of the ethnicity, gender, race, or class of the human with whom they live.

There are, of course, more effective or less effective ways of changing behavior so as not to make those who engage in it defensive, causing them to reject advice or support for the dog, like free fencing to get dogs off chains and quality food to get cats and dogs better nutrition. Aside from dog fighting which should always lead to rescue/seizure, arrest, and prosecution, we want the other behaviors to change, through education if possible, but prosecution if necessary because the welfare of animals is of consequence. But regardless of how we go about it, we need not pretend those who do not feed their dogs so they don’t have to clean up the mess aren’t being intentionally cruel. Nor should we allow the authors to pretend otherwise by claiming that this is a unique “ethnoracial” practice.

In fact, many, if not all, of their similar claims turn out not to be nothing more than commonplace manifestations of basic human nature. For example, they claim that Black people rely on “folk knowledge” or “indigenous” ways of caring for animals, such as trusting the opinions of friends, family, and neighbors over professional “experts” or relying on such individuals for assistance at the loss of housing or transportation; behaviors that are hardly culturally specific. Wealthy and White people likewise tend to trust their social peers and are more likely to believe what they read on social media than professional news sources. They are also likely to rely on friends and family for assistance when needed. Of course, people with means can rent a car, rather than rely on a friend for a ride, or afford to board their dog, rather than asking family to take him in, but fundamentally, the behaviors are similar. This is hardly surprising. Love of dogs and cats, regardless of race or income, is near universal. What is distinct is what happens if families do not have the resources to provide for veterinary care when their dogs and cats need it.

Although Rowan and Arluke appear to have wanted to write a book about the impact of race and pets, they have actually written an important book on the impact of class. They also appear to have wanted to write a book that cited skin color as a reason to condone differential levels of care, only to discover that people of color have the same views as everyone else.

Stripping away the racist distractions, their compiled evidence shows that there are three primary barriers to better care that stand in the way of lifting animals out of want and allowing poor people to act like the kind of pet owners they want to be: cost (and transportation), the regressive practices of private practice veterinarians and their industry associations, and the equally regressive practices of animal control agencies and their regressive enforcement officers.

Cost is a barrier to better care

Without access to free and low-cost medical programs, eight out of 10 pets in the poorest neighborhoods of West Charlotte, North Carolina, never see a veterinarian. Nonetheless, Rowan and Arluke rightfully argue that this doesn’t mean people on the lowest rungs of the economic ladder don’t care about their animals. To the contrary, the authors admit that, “Attachments to pets… can be as profound and lasting as among pet-owning residents in any neighborhood” but “Low-income pet owners or those living in poverty have fewer resources to express or act on their attachment.”

For example, the authors highlight the touching story of one woman who “grieved over her recently deceased 14-year-old cat but never had a photograph taken of ‘Chloe.’ So she scoured magazines to find a likeness of her cat and found one that she framed and hung in her living room.”

Moreover, Rowan and Arluke note that after implementation of a free spay/neuter program in “the most poverty-stricken” neighborhoods, where the majority of residents are Black, 80-90% sterilized their animals. Similar numbers were achieved for other medical care, such as vaccinations.

Even Rowan and Arluke concede that, “class may have more influence on these human-animal relationships than race or ethnicity.” The end result is an unsurprising and mundane conclusion: the less money people have, the less they can spend on veterinary services. Consequently, if cost is removed as a barrier, the vast majority avail themselves and their pets of it. Specifically, the data shows that the vast majority of “individuals living in or near poverty do their best to care for their animals, given severely limited resources, adverse conditions, and unpredictable crises that constantly test their ability to have a residence to live in, food to survive, utilities for comfort and health, and medical care for all members of the family, whether human or animal. In other words, the level of care they provide reflects not their intent but the structural limitations of living in or near poverty.” Follow the lack of money.

For the small percentage of poor people who do not initially get the free care offered for their pets (about 10%), Rowan and Arluke speculate that the state’s history with eugenics that forced black women to get sterilized is to blame. The evidence for this proposition is weak, with the authors admitting that it is “rare for pet owners to directly refer to the state’s forced sterilization of humans as the reason why they do not want to sterilize their animals.” Instead, the evidence suggests their hesitancy lies with a more pedestrian, though ubiquitous, tenet of human nature: embarrassment. Poor people do not want to be judged as needing a free hand out or deemed irresponsible. By offering the services in a non-judgmental way and, for those who can afford it, requiring a small co-pay, the stigma is lifted overcoming their hesitancy. Many of these individuals will then even subsequently act as “ambassadors” encouraging others in their social circles to use the services, resulting in “a flurry of calls requesting sterilization.” This conclusion is neither surprising, nor novel.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic propelled “the poverty rate into double digits,” a 2018 study found that roughly one in four pet households had difficulty getting needed veterinary care because of its high cost. This not only impacted the quality of life (and in cases where they could not afford emergency care, the actual life) of the animal, it also negatively impacted the emotional health of the people.

That same study noted that the old saw, “if you can’t afford a pet, you shouldn’t have one,” was not only oversimplified given the broad demographics of the families involved (for example, “there are also middle-class families that live paycheck to paycheck, with limited funds for veterinary care, especially when the need involves high-cost”), it was counterproductive (it does nothing to solve the problem), unfair to people of limited means, and also unfair to animals in those homes. It concluded that it would lead to more death as “29 million dogs and cats live in families that participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, also known as food stamps.” Like the evidence presented in Underdogs, the study concluded that there “is a need for a financial support system for accessing veterinary care that opens the door for more families to receive it.” In short, poor people “want to be responsible but face barriers; however, with the help of affordable veterinary care programs, they can care for the animals in ways they would like to.”

Private practice veterinarians and their regressive veterinary associations are barriers to better care

The problem is that private practice veterinarians and their associations are suspicious of pro bono veterinary services and stand in the way of their implementation. As I noted in my 2008 book Redemption, the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) has a long history, going back to the 1970s, of opposing municipal or SPCA-administered spay/neuter clinics that provided the poor an alternative to the prohibitively high prices charged by some private practice veterinarians. Despite the fact that low-cost spay/neuter services aimed at lower income people with pets had a well documented rate of success in getting more animals altered and reducing the numbers of animals surrendered to and killed by “shelters,” the AVMA would not agree to any program that they perceived threatened the profits of veterinarians, even though poor people were not, and were unlikely to ever be, their customers. In 1986, the AVMA also asked Congress to impose taxes on not-for-profits for providing spay/neuter surgeries and vaccination of animals at humane society operated clinics in order to discourage them. And to this day, aside from spay/neuter and vaccinations, veterinary associations generally prevent shelters from offering needed veterinary services to people who could not otherwise afford it and will sue, or threaten to sue, non-profit organizations that try. Rowan and Arluke note that, “The Alabama Veterinary Medical Association recently tried to pass a law banning shelters from offering veterinary services” and its North Carolina counterpart was considering similar legislation.

Animal control agencies and their regressive enforcement officers are barriers to better care

Unfortunately, private practice veterinarians are not alone in acting as a roadblock to improving the lives of the pets of the poor. Municipal pounds do, too. Rowan and Arluke cite studies that show that people living in neighborhoods with high rates of poverty are “more likely to befriend stray or feral animals of unknown origin by occasionally feeding them or briefly letting them into their homes” and “consider to be unproblematic community pets or tolerate as just part of the neighborhood landscape.” This finding mirrors those of Professor Alan Beck whose book about community dogs in Baltimore, Maryland, published almost 30 years earlier, found neighborhood dogs adopted into homes from the streets of low-income neighborhoods tended not to gain much weight as they were already getting enough to eat from handouts. Beck also found that community animals impounded by the shelter were often reclaimed and released back to the neighborhood by local residents who considered them “pets of the block.”

In contrast to how residents view these animals, Rowan, Arluke, and Beck all found that, “animal control officers see them as nuisances to be disposed of, even though local residents have not filed a complaint with the department and consider them to be shared community pets.” This not only sets up residents in an antagonistic relationship with animal services to the detriment of animals, but the problem is exacerbated because of the prohibitively high fees now charged by regressive pounds that prevent poor families from reclaiming either their own pets or community pets of the block, resulting in higher rates of killing.

Where should we go from here?

The evidence presented by Rowan and Arluke does not compel us to accept “traditional identity,” “folk…” and “indigenous” ways of relating to animals by developing “ethnoracial cultural competence.” Instead it compels us to:

Change the law to allow pro bono veterinary services, despite objections from regressive private practice veterinarians and their industry associations;Subsidize the cost of (and transportation to) that care as the vast majority of poor people (roughly 80%) will get it if those barriers are removed;

Provide that care in a non-judgmental way and for those with some means, require a small co-pay in order to win over the small percentage of poor people (roughly 10%) who are embarrassed by what they perceive negatively as a “hand out” and are reluctant to use free services for fear of being judged irresponsible. Doing so will not only increase the number of people who get veterinary care for their animals, it will turn them into “ambassadors” that encourage others in their neighborhood to do the same;

End the round up and killing of community cats and dogs by animal control officers since no one asked them to (and, even if they did, they shouldn’t); and,

Eliminate barriers to animals being reclaimed from shelters if they end up there, such as high impound fees.

To these five prescriptions, I would add a sixth: End housing discrimination for people with animal companions, since the majority of the poor rent, rather than own. Even before the pandemic, a study found that one in four renters lost their home because of a restriction on housing. In addition to protecting animals already in those homes, doing so would also allow almost nine million more animals to find new homes, roughly eight years worth of killing in U.S. pounds.

In short, we just need to treat people like people by offering “Low or no-cost sterilization, vaccination, pet food, fences, and [veterinary…] treatment.” Doing so will “go a long way towards changing the quality of life for dogs and cats and the people who want to care for them.”

For the remaining few who fight dogs, serially breed dogs, chain dogs 24/7, refuse to provide veterinary care despite that it is freely available, or don’t feed their dogs, criminal prosecution (and rescuing the pets) is both necessary and proper, regardless of the color of the abuser’s skin. Otherwise, we will have subordinated the rights of animals to the interests of those who harm them, undermining the central tenet of the animal protection movement and leaving animals in harm’s way. That is something we should never do.

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.

Nathan J. Winograd's Blog

- Nathan J. Winograd's profile

- 13 followers