Rusty Barnes's Blog: Fried Chicken and Coffee, page 8

August 4, 2016

Bear Takes a Meeting (Trinity Bridge)

Our Complaints & Questions Bureau

is based in the bottom of a dry well. We will

help you down there if you wish to file

a report on my associates’ conduct.

Which creek-bed is your favorite?

We’ll mud you in, blame accidental causes

if ever a fisherman snags on an ankle. It’s simple.

There’re zero murders on the books in Trinity,

though dying strange ways trumps the totals we lose

to natural old age. We’re the law they’ll call

to solve your mysterious disappearance.

That’s what happens if once we think

you aren’t with the program. Nod twice

if you track my meaning. Promise silence

and the tape comes off. The ropes.

We never had this friendly conversation.

Go on with your normal day

and let’s not talk again.

TODD MERCER won the Dyer-Ives Kent County Prize for Poetry in 2016, the National Writers Series Poetry Prize for 2016, and the Grand Rapids Festival of the Arts Flash Fiction Award for 2015. His digital chapbook, Life-wish Maintenance, appeared at Right Hand Pointing. Mercer’s recent poetry and fiction appear in: Bartleby Snopes, Blast Furnace, Cheap Pop, Eunoia Review, The Fib Review, Flash Frontier Magazine, Fried Chicken and Coffee, In-flight Literary Magazine, The Lake, The Magnolia Review, Softblow Journal, Star 82 Review and Two Cities Review.

TODD MERCER won the Dyer-Ives Kent County Prize for Poetry in 2016, the National Writers Series Poetry Prize for 2016, and the Grand Rapids Festival of the Arts Flash Fiction Award for 2015. His digital chapbook, Life-wish Maintenance, appeared at Right Hand Pointing. Mercer’s recent poetry and fiction appear in: Bartleby Snopes, Blast Furnace, Cheap Pop, Eunoia Review, The Fib Review, Flash Frontier Magazine, Fried Chicken and Coffee, In-flight Literary Magazine, The Lake, The Magnolia Review, Softblow Journal, Star 82 Review and Two Cities Review.

August 1, 2016

Anna, Whose Last Name Is Covered In Lichens, 1851-1920, poem by Matt Prater

And I was there as well, I saw. My hands, too,

went out and made the world. I did not

only imagine the soldiers, I touched them.

I soothed, with cool rags, the dying Johnny soldier;

I soothed, with cool rags, the dying Michiganite;

I caressed their tender knobbed muscles, tender paunch;

soldered, with iron set to the banked blaze, more iron;

slammed the errant wagon wheel in place;

hammered in the things for hammering;

wiped the drooling face of the orphaned cow

whose mother was stolen by Lincolnites;

and dreamed to caress the tender muscle

of one Lincolnite who robbed as Robin Hood,

who spied me one whole week from a distant ridge

as I went through my nurse and farm girl chores,

and when he had stolen our second stolen cow

left me my allotted pitcher of blue cream. Know:

I, too, would have tendered my body on the field,

though I was tender, tender as any boy who could not say it–

who I would’ve killed, or as easily’ve doused,

at the first request, with my amorous wet.

Matt Prater is a poet and writer from Saltville, VA. Winner of both the George Scarbrough Prize for Poetry and the James Still Prize for Short Story, his work has appeared in a number of journals, including Appalachian Heritage, The Honest Ulsterman, The Moth, and Still. He is currently an MFA candidate in poetry at Virginia Tech.

Matt Prater is a poet and writer from Saltville, VA. Winner of both the George Scarbrough Prize for Poetry and the James Still Prize for Short Story, his work has appeared in a number of journals, including Appalachian Heritage, The Honest Ulsterman, The Moth, and Still. He is currently an MFA candidate in poetry at Virginia Tech.

July 29, 2016

I Hear You Weeping, fiction by Robb T. White

Jimmy Shannon from Sheboygan, as he liked to introduce himself to people who came into his bar, had never been to Wisconsin in his life. He’d done time for check forgery in Michigan and three years in Pennsylvania for hustling a widow with Alzheimer’s out of twenty-eight thousand dollars. The judge also ordered him to pay restitution, but Jimmy had picked up some new tricks in prison; once he’d reported to his probation officer after serving eighteen months and gaining early release, he was a gone goose—skipping straight across the state line to Ohio. His cellie was a career forger, and Jimmy admired him. He told Jimmy for three or four thousand he could get new papers and a Social Security card that would stand up to a check.

A few weeks of boozing in bars and making casual conversation led him to Cleveland where he found a guy who knew a guy—and so on through a long list of bullshitters, wasting a few hundred of the widow’s cash on these losers, until he ultimately hit pay dirt. It cost him a thousand more than his cell mate said it would but Jimmy felt it was worth it because he was going legit from here on out. Although his cellie made thousands on his scams, and Jimmy believed him, he was oblivious to something Jimmy realized when the bars clanged shut on him once more: he wasn’t going to die young. Doing jail in your forties is not like some gangbanger going in where it’s a rite of passage. Jimmy’s hair was turning gray and last week he noticed a bald spot on the back of his head the size of a grapefruit.

Jimmy was a natural talker and tending bar was more an avocation than a job to him. He’d put up almost all the rest of his cash on this dump of a bar at the end of the Strip in this second-rate resort town. It had gone through several transformations before Jimmy’s ownership from a psychedelic lounge in the sixties with black lighting through a country-western bar with a mechanical bull to its current state as a sleazy trysting spot for cheating spouses. Its fading red-and-black décor with velveteen booths was its final makeover. The bank that owned it as a result of forfeiture had given him generous points on the loan in the hope of unloading it before it gasped its last breath and the dozers flattened it for a parking lot for the restaurant next door.

But Jimmy had a plan that involved using the rest of the widow’s money on an expensive sound system. Jimmy had looked over the bars on the Strip and he came to the conclusion that the twenty-somethings were not being served by the rash of shitkicker and punk-goth-grunge combos everywhere else.

Jimmy’s gamble was paying off at the right time: it was the height of the tourist season and all the college kids were looking for places to drink and hook up. Jimmy installed a DJ for weekends and the autotracked, fast-beat techno music hit the right nerve with this crowd. He’s already hired two more serving girls for week nights because the word was out and Raul’s—Jimmy’s exotic-sounding brainstorm the day he signed the papers—was taking off. Jimmy took a kickback from two drug dealers peddling Ex in his place. What the hell, he thought, they’d be selling it anyway. Jimmy also paid off one of the beat cops to tell him when vice was hanging around. Sometimes jimmy wished he could talk to his cell mate again. He’d tell him how he had learned from his errors of the past. “Pay the right people off and don’t whine about it,” Jimmy said into his mirror while shaving, as if he were talking to Harry as they used to do at nights after lights out in the bunks. He nodded his head sagely at himself. “Greed will get you right back in the slammer with Harry,” he added. He winked to his image before leaving the rental cottage. Jimmy had plans for this aspect of his new life, too: he’d be financially able to return to the bank and apply for a house loan.

Jimmy had one small problem and he meant to deal with her today. Some old hag of a bar fly had decided to drink in Raul’s and, though this wasn’t affecting the bottom line (Jimmy was using lots of financial lingo these days in his swagger mode), it was irksome to see this disgusting old crone in her frumpy clothes come into his bar to finish up her nightly boozing.

Last night, for example, a couple young girls were chatting her up while waiting to be served at the bar—just mocking her, Jimmy knew—but instead of being offended, the ugly old bitch basked in their flattery. She did something that made Jimmy’s stomach churn with acid. She popped out her dentures and gummed the air like an old snapping turtle. The girls shrieked with laughter, but Jimmy saw a red mist come over his eyes.

Most of the time, when a new customer entered Raul’s and looked around, that person, male or female, knew right away whether this was the right place. Most of the white-haired tourists who stumbled into the place by mistake had the good sense to down their mixed drinks and piss off. Certainly, by the time the serious night crowds began to gather on the Strip, the oldsters knew better than to drink in Raul’s. Jimmy had given his bartenders and bouncers tips on how to discourage these types from frequenting his oh-so-trendy place. There were exceptions: middle-aged-guys on the prowl with credit cards and cash to burn in their pockets. “You see one of these older dudes on a pussy prowl,” Jimmy ordered his staff, “keep the drinks coming and get them to buy rounds for the ladies.” He showed them how to mark the receipts so that Jimmy could give them bonuses in their paychecks. Las Vegas had its whales; Jimmy had his select group of horny husbands who each dropped several hundred a week in his place.

Jimmy’s dream was to expand. There was an old cement-block, hillbilly bar that Jimmy had his eye on. The Strip was crawling with teenaged runaways—girls who would trick for a little dope money. He’d have no shortage of gorgeous, hot-looking strippers. Once Jimmy had the chamber of commerce president, the precinct commander, and the mayor in his pocket, he was going to seek a change in the city ordinances that would permit a “gentleman’s club.” Two of the three were regulars at Raul’s anyway. It was just a matter of getting that dim-bulb mayor to go along with it. If he didn’t bite at a bribe, Jimmy thought, he’d go the next route, which was to help his own candidate get elected. Jimmy was silently hand-picking potential candidates for that position from among his clientele.

But the street hag had to go first. She was a nuisance and an eyesore. Tonight was the night he would put his plan into motion.

That night while the music was pumping bass guitar riffs through the speakers, jimmy watched his bartender go up to the witch and lean over her. It was too loud to hear a word even if he were sitting on the next stool, but he watched the harpy palm the fifty-dollar bill Jimmy’s man left. She looked about as if she couldn’t believe her luck, then she swiveled her huge behind off the stool and made for the door.

“Good riddance,” Jimmy said watching her go and hoisted his drink in the direction of his bartender, who winked back at him.

“See, Harry,” Jimmy told himself grandiosely, “that’s where you made your mistake. Pay up and your problems go away like that.” He snapped his fingers to put an exclamation point to his own sagacity. “Poor Harry,” he sighed to himself. “That’s why he’s in there and I’m out here.”

She was back the next night—and the night after that, and the nights after that.

The fifty was replaced by a c-note and a simple but precise explanation what the money was for. Jimmy had his bartender practice it in front of him. “Make sure the goddamned old simpleton gets it this time,” Jimmy said with too much heat.

The woman had an iron gullet for all the booze she put away. But she knew how to nurse her last drink until almost closing time and the more prominent she was, sitting alone down there at the end of the bar, the angrier Jimmy became. He fantasized smashing a bottle of Four Roses over her skull (Jimmy wouldn’t waste a good brand on her). Sometimes it was the bouncer’s fish billy he used in his imagination; he could hear the crack and see the fractures like spider webs crisscrossing the skull bone.

But there she was again, night after night. Jimmy was getting ulcers over it.

“No more Mister Nice Guy,” he told his bartender when he reported for work, “I’ll handle it myself.”

Jimmy sidled over to her after he’d seen her down her fourth Rum-and-Coke of the night. He set a new drink in front of her and said, “Hi there, I’m Jimmy from Sheboygan.”

She eyed him and then the drink he was sliding toward her. She grunted something and wrapped her thick fist around the glass. Jimmy barely kept his grin in check. The drink was spiked with a tab of acid he’d bought on the street.

Jimmy stayed near the end of the bar pretending to polish glasses while he watched for a reaction. About fifteen minutes later, half the drink gone, she started to fidget. Jimmy had to turn his back so that no one could see him laughing.

The scream that erupted from her throat was loud enough to pierce through the music. The old woman fell off the stool, and hoisted herself to her hands and knees. She looked like a spavined horse having a seizure. Her mouth hung open and she gasped for breath like a dying fish on the shoreline.

Then, like magic, as if she were a suddenly nimble twenty-something herself, she scrambled to her feet and fled out the door nearly knocking over a young man just entering.

Jimmy experienced a pang of fear. “What if she dies, stumbled into traffic, gets run over . . .?” Thoughts like these haunted him all night until closing.

He never saw her again. Whatever guilt he felt that night was long gone and he was moving forward with his plans to purchase Jimmy II, his name for the strip-bar-to-be. Things were going so well that he could afford to lose a few bucks before he had all his chess pieces lined up for the switch to the gentleman’s club.

His regular bartender didn’t show that night so Jimmy had to fill in to keep the drinks moving back and forth. Jimmy realized he loved his work and his life was finally in the right place.

“You see, Harry,” he said, summoning his ex-cell mate’s familiar ghost, to read yet another lesson learned—or, in Harry’s case—unlearned. “You have to deal with every problem when it arises. Don’t treat small problems as insignificant. That’s how snowflakes accumulate to become avalanches.” Jimmy had forgotten that it was Harry who had lectured him about the old sociologist’s maxim of the broken-window theory. “One broken window, Harry, means ninety-nine are going to follow it sooner or later,” Jimmy would say when his staff couldn’t overhear.

Jimmy had an extra shot-and-beer at closing, a reward for pitching in, not holding back like a boss and looking for someone else to fill in.

He was out as soon as his head hit the pillow.

Jimmy thought the light penetrating his eyeballs was too much sunlight this early. He must have forgotten to pull the shades near his bed in his exhausted state.

When he opened his eyes fully, he knew it was something else. The old limbic brain at the base of his spine was tingling a warning sign. This wasn’t ordinary sunlight but a flashlight probing his eyes and face.

Jimmy sat straight up in bed as if electrocuted.

Mother of God, Jimmy realized as his brain collected itself and understood the image. Someone was in his bedroom.

That someone put on the room lights. That someone was a very big, bearded male in his late thirties. He wore denims and a vest with—Oh God—outlaw biker patches. Jimmy saw the Mongols logo, the one-percenter patch and, worst of all, the dozens of scrambled tattoos up and down the man’s massive arms. Jimmy heard men in boots walking around downstairs. “My friends,” the big biker said, “you don’t mind, right?”

“No,” Jimmy said, “help yourself. Take my money. I think I have a few hundred in my wallet.”

The biker smirked at him as if that were something funny.

“I can get the night receipts,” Jimmy offered. “There’s at least three thousand, all cash, small bills. Please . . . please take it and go.”

“It’s not your money we want, Shannon. It’s your bar. I have a paper for you to sign—”

He took out a wad of folded papers from his back pocket and tossed it to Jimmy.

Jimmy realized, with a sickening dread, these were in fact legal papers. He noted the pathetic figure entered as the sale price.

As if reading his mind, the biker said, “I know how much cash you have in the house and how much you keep in the bar and I know to the penny how much you have in your bank accounts, personal and business. You’ll be able to pay taxes on the sale and then you can skip town with your life.”

“What if I don’t sign?” Jimmy was astounded at the courage he mustered just to get that out, say it to this brute.

Without raising his voice, the biker said, “Don’t matter. You’ll disappear. That’s what them dudes downstairs is for. Your call. I’ll give you five minutes to think it over. I’m going for a beer and when I’m done, I’ll be back up to see what your answer is.”

Jimmy watched him go. He noticed his cell phone and wallet weren’t on the bureau top where he placed them every night after work. He leaned over the side of the bed and noticed that the phone jack was still in the outlet but it had been cut in half.

Time stopped in its tracks; it seemed seconds had passed but he heard the heavy tread of the big man coming back up.

“What’s it to be?”

“I’ll sign, I’ll sign your paper,” Jimmy said.

Jimmy signed the document and handed it to the biker who folded it haphazardly and thrust it inside his grotty Levi’s. “Now we got us one more thing to clear up,” he said and reached down where he groped under the bed and came up with the Louisville slugger Jimmy had put there when he first moved in and long since forgotten about.

He watched the biker’s big fist wrap itself around the meat end of the bat and clean it of the dust that had gathered on its sleek varnished surface.

“What—what are you doing?” Jimmy whispered, half-choking on his words. “I signed the paper.”

“Yeah, man, you did.”

The man didn’t even look at Jimmy as he took a practice swing that made the air ripple around Jimmy’s head. “That was business. This is personal. You’re going to be in the hospital for a long time. When you get out, you get out of town. Understand?”

“What—what are you saying?”

“You gave my old mother a mickey finn. She spent a week in the hospital, crying every day. She wrote me about it. When I got paroled at Chillicothe for good behavior, I decided to come see the lowlife prick that would do something that shitty to a harmless old lady.”

Jimmy said nothing; he waited for the blow without taking his eyes off the biker. He hoped he’d go unconscious right away and not too many bones would be broken when it was over. When the biker approached him from the side of the bed where he had more clearance for a good swing, Jimmy shut his eyes. He heard Harry’s ghost snickering in his head: “I told you, Jimmy. I told you always to treat your mark like you’d treat your own mother.”

The bat took Jimmy under the jaw. Before the citadel of his brain could register it and assess the damage from nerves shooting from jaw, broken teeth, and bloodied, impaled lips, he was back in the same pod, the very same cell with Harry, who was standing there shaking his head in dismay at Jimmy’s return. Jimmy tried to explain, tried to tell him about that irritating old woman, but somewhere deep below his feet—below the entire prison tier—a rumbling, whirling, black vortex was sucking in all his words and thoughts and, finally, the heaving sobs pouring out of his chest and spilling into the air.

Robb White publishes the Tom Haftmann private-eye series, most recently Nocturne for Madness. He has two noir mysteries: When You Run with Wolves and Waiting on a Bridge of Maggots. He has a collection of short stories: ‘Out of Breath’ and Other Stories. Special Collections won the Electronic Book Competition of 2014 by New Rivers Press.

Robb White publishes the Tom Haftmann private-eye series, most recently Nocturne for Madness. He has two noir mysteries: When You Run with Wolves and Waiting on a Bridge of Maggots. He has a collection of short stories: ‘Out of Breath’ and Other Stories. Special Collections won the Electronic Book Competition of 2014 by New Rivers Press.

July 26, 2016

The Last Thanksgiving, poem by Taylor Collier

first appeared in Tar River Poetry Spring 2010

During dinner my uncle’s behind the house

helping a heifer through her first delivery.

Inside, dry turkey, hot dinner rolls.

The heifer’s cries bellowing through the house.

Green beans, sweet potatoes, and cornbread

stuffing. All with the tang of

this might be his last.

And who even remembers?

I’m staring out the back window

at the heifer’s uterus prolapsed

on the muddy grass.

The vet and my uncle hose it

with peroxide and shove it back

inside like a beating heart into a wine bottle.

The trees haven’t even begun to turn,

and my grandfather can still speak.

Knowing we will soon be gone,

he’s telling every dirty joke he can remember. Taylor Collier currently lives in Tallahassee. Work has appeared or is forthcoming in some places like Birdfeast, The Journal of Applied Poetics, The Laurel Review, Nightblock, Rattle, Smartish Pace, Tar River, Zone 3, and others. More poems and writing about poetry at taylorcollier.com.

Taylor Collier currently lives in Tallahassee. Work has appeared or is forthcoming in some places like Birdfeast, The Journal of Applied Poetics, The Laurel Review, Nightblock, Rattle, Smartish Pace, Tar River, Zone 3, and others. More poems and writing about poetry at taylorcollier.com.

July 23, 2016

A Redneck Eats Thai Food, essay by William Matthew McCarter

I can still remember those dark days–not long ago–when you couldn’t hang out with a group of grad students at a university campus without someone saying “Let’s go get some ethnic food”–like they had just smoked a bourgeois blunt and had a bad case of the middle class munchies. Somehow, some way, we always seemed to wind up at a Thai restaurant, as if Thai food was the communion wafer of the bourgeois multicultural sect. I hated Thai food and still do, but I had a part to play on this graduate school stage and didn’t need anyone staring at me because I refused to take part in the communion of middle class white people.

Thai Food Restaurants–they were like a law of nature. Newton himself might have proposed it: objects in motion tend to stay in motion and middle class bohemian wannabes tend to go eat Thai food. If you went to a poetry reading–if you were a young bohemian–you went to the Thai restaurant. It was as true in Fat Chance, Arkansas and Slim Pickens, Oklahoma as it was in New York or LA. Wherever two or more middle class graduate students are gathered in the name of art, there is a Thai Restaurant among you. At times, these merchants of bohemian culture will make the token gesture of asking for your opinion–“You do like Thai food, don’t you?”–with a tone that sounds very much like “you do breathe in oxygen, don’t you?” But for the most part, it was a given, especially at the poetry readings or writing workshops: you read someone’s work, comment, others comment, critiques were passed around, sometimes complaints about critiques followed and then you adjourned for the Thai restaurant. I mean after all. . . you breathe oxygen right?

I have nothing against Thai restaurants. They all seem like regular Chinese food restaurants except they tend to have fancier table cloths and, for some reason, better egg rolls. It was the inevitability of going there that created my rancor–and the suburban white kid presumption that I must like it because “I breathe oxygen.” Oh, and the growing suspicion that somehow I lived among people for whom–no matter what their taste buds truly begged for on a given night–the Thai restaurant represented a moral decision. Pad Thai was some kind of a cosmopolitan ethical choice in a way that Frank’s all night diner wasn’t.

You’d drive right by places like Frank’s where you knew the ambrosial scent of the two by four–two eggs, two pieces of bacon, two sausage patties, and two potato pancakes– was bountiful in the air, or a heavenly portion of Frank’s blue plate special–pot roast–was crashing like a meteor into a heaping pile of mashed potatoes, or across the street at Sal’s, a deep-dish supreme pizza, heaping full of toppings all stuck together with a mixture of provel and mozzarella–a pizza fit for the gods and fresh out of the oven–a pizza searching for that cracked red pepper and grated Parmesan. . . and there you were, with “Love Is Like Oxygen” playing on the radio, thinking to yourself “Thai food must be like oxygen too” as you step out of the car and walk toward the doorway to the Thai Restaurant. And to think that we passed by the legendary Joe Willy’s and I had to wave goodbye to the chicken fried steak on my way to the fuckin’ Thai restaurant.

To suggest that you, the great unwashed, might actually prefer a chicken fried steak smothered with gravy became one of those truths that just could not be uttered. “I’d prefer a big hunk of meatloaf and some beans and greens tonight,” was verboten. That is the bourgeois bohemian equivalent of walking into a trailer park in High Ridge, Missouri and yelling “Walmart sucks” with a bullhorn. Truth be told, I would trade every Thai restaurant in the world for a BBQ pulled pork sandwich and cole slaw or a chili dog at the A&W. Or The Pig’s Country Fried Chicken Platter or a slab of dry rub at Cory’s. And. . . I long for the day when the bourgeois bohemian sect discovers Trans Appalachia–the beautiful fourth world country that stretches from western Carolina to Arkansas–and wants to show its solidarity with the oppressed downtrodden people of that region. And. . . makes the moral choice to go eat Chicken and Dumplings after a poetry workshop. “You do like turnip greens, don’t you?”

July 20, 2016

Two Poems, by Adrian C. Louis

Invisible Places of Refuge

Deep inside myself,

I am running out

of places to hide.

I am an old man,

a dirty old man &

the world we knew

is fading fast away.

I cannot say how I

became covered with

the cobwebs common

to poor & broken folk.

Darling, I cannot say

if I’m spider or fly.

***

My love, I pray that you

can not see me now, but

of course you can see me

& yes, I am a walking scar,

one of life’s miracles, but

you’re just a ghost, still,

the only ghost that I

dream hard about.

I will never hide from

the haunting you offer.

***

Soon I will need no

invisible places of refuge.

While other spirits float

through a dire dampness

of tears & wet kisses, I

will flitter about, brittle &

arid as pack of Top Ramen.

***

How I love my Top Ramen.

Top Ramen is my hemlock.

It shrinks my body & soul.

My body has grown thin

& my shadow so skeletal

that it often hides from me

& the palaces of memory,

from all that I’ve known.

Dear Gods of my known

& unknown universes.

I thank you for the sweet,

sweet & holy miracle

of noodles made from

the baked & pulverized

bones of poor folk.

Ratiocination

I am a ghost who hates

Rapid City, South Dakota

but I need it occasionally

like a low-dose tweeker

with a weekend habit.

Exiting late Friday mass

at some execrable saloon, I

see some idiot has barfed

a blizzard of gizzards right

next to my shiny, white SUV.

I’m guessing they’re gizzards

because the hipster bistro

across the street sells them.

Gizzards from ghost chickens.

Oh, my country…

My country ‘tis of thee

sweet land of gizzardry.

Adrian C. Louis

Adrian C. Louis grew in northern Nevada and is an enrolled member of the Lovelock Paiute Tribe. From 1984-97, Louis taught at Oglala Lakota College on the Pine Ridge Reservation of South Dakota. He recently retired as Professor of English at Minnesota State University in Marshall. His most recent book of poems is Random Exorcisms (Pleiades Press, 2016). More info at Adrian-C-Louis.com

July 19, 2016

Brothers, fiction by Juan Ochoa

It was a big family. So much so that Ama Quina was still having babies when her oldest children started families of their own. The initial significance of this overlapping was that Ama Quina functioned as wet nurse for her grandchildren not long after she had weaned her two youngest boys Sergio and Roy, El Polaco—he was called that because his skin was so light he looked Polish. Ama Quina’s nueras, daughters-in-law, were not happy about handing over their babies for another woman to nurse, but the young brides’ hands were needed in the fields as was the extra paycheck.

The children also learned the importance of work and getting paid. When they were old enough to walk, each child followed the family to the field to pitch in and help with the work. Since the kids were raised so close together and with everyone sharing duties, they did not observe the formalities of family titles as is the custom. The grandparents and heads of the clan, Ama Quina and Apa Cheto, were the only ones to carry a title before their names. For the rest, there were no titles to distinguish one member of the family from the next like tío, tía, primo, prima, hermano, etc. So the children of their second oldest son Julio, Gilbert and Davey, grew up like little brothers to their uncles Checo and el Polaco and called them by their first name instead of tío even though the uncles were years older than the kids. Whenever anyone outside the family commented on this “falta de respeto,” Julio would respond, “Es culpa de uno for not teaching them any better.” The only way to distinguish which child belonged to each couple was at night when the clan broke up after work and everyone retired to their respective rooms, which were just that, cuartitos, one room shacks that the patron lent the field workers. Following an accident, Julio was laid up in one of these rooms because his hand had been almost severed when it was caught in a spiked press the men were trying to move without the aid of a tractor. His wife, Anita, had pleaded with the doctor to save her husband’s hand, and when this did not move the surgeon to action she wrote down his name and was very careful of the spelling because she did not want to make a mistake when her husband woke without his right hand and asked for the name of the man “he must kill for leaving him crippled.” The surgery lasted eight hours and there was six months of bed rest before Julio could move around with his arm in a sling. The hand was still attached, swollen and for the time being useless, but the fingers moved under the thick white gauze more and more everyday and the burning around his wrist where the spike had bitten and torn his flesh was now almost bearable. He could have enjoyed the time away from the fields had it not been for the constant complaining and quarreling he faced each evening when his wife and kids came back from the campo.

While injured, Julio had to rely on the paychecks of his little brothers, Checo and El Polaco, to sustain his family. But the way Anita told it, she was the only one doing for the family, staying longer in the fields, running back to the cuartito to see to his hand and cooking the midday meal. Julio thought his wife a chiflada who didn’t appreciate the help they were getting from Checo and el Polaco. Even Gilbert at ten and Davy only nine years old picked more grapes than she did. This reminded Julio of another of his troubles. Gilbert and Davy had gotten harder to manage for Anita. The boys ran away from her in the fields and preferred to pick the rows next to their uncles Checo and Polaco instead of next to their mother where she could keep better track of the money they were earning. Anita, Julio thought, just didn’t understand boys; it was only natural for them to choose other boys for company over their mother. Julio was at least thankful that Checo and Roy salieron buenos as far as brothers go.

One evening when Anita came home herding the boys in front of her, Julio thought about slipping out of the shack and eating dinner somewhere else. Davy was marching ahead of his mother clutching his pants and howling continuously, his sobs only interrupted by sudden attacks of hiccups. Gilbert walked with a more deliberate pace between his little brother and his mother. His cheeks were streaked with furrowed rows of dust where tears had fallen.

“¿Qué paso?” Julio asked his wife as the group came nearer.

“Tus queridos hermanos,” Anita hissed pushing Gilbert who had all but stopped in his tracks at the sound of his father’s voice. “Checo and Polaco were making them fight again. Why don’t they fight themselves if they want to see a fight? Why do they have to pick on my babies?”

“Oh, that’s how boys play,” Julio said stepping out of the doorway so the group could pass. “You keep calling them babies and they’ll never grow up. My brothers are just trying to toughen them up.”

Anita turned in the middle of the room. “Toughen them up? I found them wrestling in the dirt with their pants around their knees. How does that make them tough?”

Julio looked at his boys. Davy was still crying. Gilbert was trying hard to shrink into the furthest corner in the room. “They were just playing.”

“Checo and Polaco were poking their little butts with sticks, laughing like idiotas while my babies cried in the dirt.” Anita’s eyes were rimmed with tears and the veins in her neck looked like they were about to leap out of her skin.

“¿Qué dices?”

“Algo paso, Julio,” Anita screamed. “Your brothers did something to my babies.”

Julio paced the room like a kenneled dog. His hand throbbed more now than it had all day. Davy had begun a new bout with the hiccups that threatened to drown out Anita’s shouting. Gilbert had his face buried in the corner, crying in silence.

“No paso nada,” Julio said rubbing his wrist. “No paso nada.”

“Algo paso, Julio. Your brothers did something to my babies.”

“No paso nada,” Julio shouted. “They’re helping us, without their checks we couldn’t buy food.” He moved on Davy, grabbing him by the arm with his good hand and lifting his bandaged hand in the sling over the boy’s head. “Verdad que no paso nada,” he demanded from the boy. Davy was silent for a moment then began crying anew. Anita lunged at Julio, crashing into his bandaged wrist as she screamed, “Poco hombre.” Julio winced with pain, released his hold on Davy then shoved Anita to the floor, where she stayed.

Gilbert ran to his mother’s arms, but she pushed him away and covered her face to cry. Gilbert kneeled next to his mother sobbing, “No paso nada. No paso nada.”

Later, Davy woke in the middle of the night screaming from a nightmare, the first of many. In a couple of weeks, the nightmares came accompanied by incidents of sleepwalking. They tried tying a string to the boy while he slept then attaching the other end around Julio’s foot so he could feel if the child got up in the middle of the night. But this only caused the boy to wake up throwing fits, punching, and kicking like a captured savage.

Daytime rivaled the night in its lack of peace. Gilbert and Davy could not get within arm’s reach of each other without becoming a tangled mass of kicking feet and gouging fists. The boys’ fights caused Julio and Anita to quarrel. The quarrels gave the rest of the camp more to talk about.

Anita and Julio took Davy to Ama Quina for a limpia. Ama Quina rubbed an egg over Davy then cracked it and emptied its contents into a glass of water. The yolk was stained in the center with blood, a true sign of mal de ojo. She took a broom and swept over the boy and then made him hold his head under a towel over a bowl of burning herbs. She frothed the boy in alcohol and wrapped him in sheets. Drying her hands on her apron, Ama Quina said, “Si esto no lo cura, llévalo de aquí.”

The camp was talking about Julio’s poor luck. His hand all broke up and on top of that a sick kid. But this wasn’t all that was being said. Julio’s older brother Ines told their sister Lola about how Checo and Roy were joking about making Davy and Gilbert play with their chilitos. Chetito was heard talking with Mel and Rafa about how Checo had told him how he held Davy and the funny garbled noises Davy made when Checo made him kiss Gilbert’s pipi. More details leaked out, but no one can be sure what is true and what has been exaggerated when talking about these things.

No one but Checo and Roy—with skin so fair he looked Polish—could know how surprised Davy and Gilbert looked when they sneaked up behind them as the boys peed. Only Checo and Roy can close their eyes and see the baffled look on Davy and Gilbert’s face when Checo asked them, “Who’s bigger?”

“I’m older,” Gilbert said.

“But I’m bigger,” Davy said still peeing.

“Let’s see,” Roy said grabbing Gilbert between the legs. Roy locked Gilbert’s hands behind his back and with his free hand reached around and finished pulling the boy’s pants and underwear down, all the while shrieking with laughter. Checo had Davy from behind by the elbows, shorts dropped to the knees, grinding the boys butt into his crotch and yelling, “Look, the little girl likes it.”

“Look at Gilbert’s pretty chilito,” Roy said. “Make him kiss it.”

Checo pushed Davy’s face between Gilbert’s legs. Davy screamed but was muffled by a mouthful of flesh. Gilbert bawled with pain and tried desperately to break free but he was busy trying to get his eyes to close tighter, tighter. When the boys were finally turned loose, they stood facing each other, panting. Davy, feeling a betrayal he could not understand and because he didn’t’ know what else to do, punched his brother in the face as hard as he could. The blow seemed to wake Gilbert out of a trance and he lunged at his little brother knocking him to the ground. They rolled around in the dirt until their mother appeared and Checo and Roy ran off laughing like idiots.

Apa Cheto and the older brothers gathered some money to help Julio move his family to a neighboring ranch that needed a new foreman. His hand was almost fully healed and would be as good as new by the time the harvesting season started again. Two years after that, Julio was able to move his family out of state to Texas where he found an even better job driving a truck for a lumber yard in Houston.

Davy’s nightmares became less frequent with every move but never really went away. As time passed, the family talked less and less about the nightmares and more and more about how Gilbert and Davy, even now as young men, couldn’t be in the same room with each other without getting into a fight. Everyone agreed that it was very sad that the two boys never learned to get along like brothers.

Juan Ochoa lives and writes on the Mex-Tex border. Ochoa is the author of Mariguano: a novel. Ochoa opposes slavery so he advocates for immigration reform.

Juan Ochoa lives and writes on the Mex-Tex border. Ochoa is the author of Mariguano: a novel. Ochoa opposes slavery so he advocates for immigration reform.

July 17, 2016

Dot the I’s and Cross the T’s , poem by Joy Bowman

On her deathbed she asks me if I can still play

the piano, and begins to sing of jasper roads.

I search the linen for forgotten crochet needles

she swears are under the cushions.

Her hands never stop moving, trembling out

letter after letter into the air, spelling something

intangible, something liquid. Never forgetting

to stab her finger at the end of each line.

After she is buried, I hang no basil

and pray to a god I do not know, but fear.

Receiving no answer, I pray to her instead,

and finally to something quiet and unnamable.

I imagine a silver cord still exists between us,

not yet buried by the snowfall.

Somewhere between here and there,

I find her in a mildewed trailer,

next to Highway 30, heading east.

I tell her I have my car waiting out back,

you don’t have to stay here.

In the backyard my father is dowsing for water,

she has a headache so my palms begin to spill

salt over her gray hair.

I try to take her cold hand into my mine,

but she does not reciprocate, they remain fixed

melded into the porch banister.

Instead her eyes, milky and bewildered, stare

into the darkness searching the dim hills,

looking out into the distance somewhere.

Joy Bowman lives and writes in eastern Kentucky. Her work can also be found in the anthology Feel It With Your Eyes: Writing Inspirited by the University of Kentucky Art Museum. She is a practicing hermit.

Joy Bowman lives and writes in eastern Kentucky. Her work can also be found in the anthology Feel It With Your Eyes: Writing Inspirited by the University of Kentucky Art Museum. She is a practicing hermit.

July 10, 2016

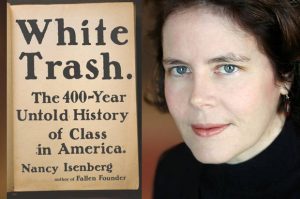

The Deep Roots of White Trash: A Review by Kate Tuttle

Nancy Isenberg Copyright Penguin/Mindy Stricke

“Americans like the rhetoric of equality but they don’t like it when it’s real.”

Nancy Isenberg’s book “White Trash” begins by looking at the characters in “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Both the book and the movie play with the divide between Atticus Finch, who is saintly and proper, and the poor white family, the Ewells, whose daughter’s false rape accusation is at the story’s center, as an example that there are two kinds of white people in the South. The book has been on Isenberg’s curriculum for 15 years, as part of a history class called “Crime, Conspiracy, and Courtroom Dramas,” which she teaches at Louisiana State University.

From “Mockingbird,” Isenberg’s book travels back to the first English arrivals on the American shore, tracing four centuries of how we talk and think about class (and race) in our most unequal union. It’s a bracing, sometimes upsetting read, beginning with its name, a term which still causes deep offense in some quarters.

When did you first start working on the idea of the “poor white” or “poor white trash?”

When you’re a historian, you gravitate toward certain issues. Part of it has to do with my graduate training; my first book dealt with race, class and gender. But it also had to do with when I was working on “Madison and Jefferson,” which I coauthored with Andrew Burstein. I became very aware of the importance of how Jefferson talked about the poor. He has this amazing line where, at the same moment that he’s calling for the education of the poor, something the Virginia legislature would reject, he refers to the poor as “rubbish.” I became interested in figuring out the language: how do Americans talk about the poor? And then I realized that this is connected to the larger problem Americans have about class, that they believe a myth. We are told over and over again by writers, sometimes journalists, but mainly politicians, that we are an exceptional country, that we embrace the American dream. And what’s that rooted to this idea that we believe in social mobility. And we think that that idea, that promise, goes all the way back to the American revolution, that at that moment we broke free from the British system and that somehow we unburdened ourselves from the English class system. Now this is a problem that Americans have – they often prefer the myth over reality.

I began to look more closely at how Americans talk about class. There are a long list of slurs and of terms such as waste people, vagrants, rascals, rubbish, lubbers, squatters, crackers, clay-eaters, degenerates, rednecks, and of course, trailer trash. And you’ll see that just by paying attention to the words people use … what comes up over and over again, is the way the discussion of class throughout our history has forced on the centrality of land and land ownership, as well as what I call breeds, or breeding. And both of these big concepts come from the British. For example, the early indentured servants, the poor who the British wanted to dump into British colonial America, they were called waste people. And where does that term come from? It comes from the idea of waste land.

If a rich field, a productive field, is the sign of success, then fallow and untilled soil, soul that is ignored, the scrubby, swampy, completely worthless tract of land, is what waste land was. We forget – through most of our history we were an agrarian nation. That means that land ownership was the most important marker for designating an individual – and course we’re talking about, primarily, men – it was the most important signifier of civic identity, it was the first way to measure who had the right to vote, it also was a measure of independence. Americans didn’t believe everybody was free, you were only free if you had the economic wherewithal to control your destiny and where did that come from? It came from owning land.

More at:

http://www.salon.com/2016/07/09/the_deep_roots_of_white_trash_in_america_not_only_are_we_not_a_post_racial_society_we_are_certainly_not_a_post_class_society/

June 21, 2016

Field Fire, fiction by Paul Heatley

Bobby woke in his truck, the rim of his hat pulled low to cover his eyes. Rising sunlight hit him full in the face when he lifted it. He winced, blinked until he could handle it, then reached for the warm bottle of water in the centre console. It was half-empty. He drained off what was left, but still his throat was dry. It burned, and it wasn’t just his throat – everything else hurt, too. His right hand was swollen, the knuckles purple. He looked back at the bar behind him, the cars and trucks parked in front and around where he was near the bottom of the lot. In front of the building there was a row of motorcycles. A couple of bikers had fallen asleep in the saddle, and a couple of others were laying splayed on the ground or atop the benches on the sun-bleached grass.

Bobby got out the truck, stretched, then strolled up to the bar. It was dark inside, only a few lights on, but it was blissfully cool. The bartender looked up as he entered, raised one eyebrow. “We’re closed,” he said. He scowled. He sat on a stool behind the counter, reading a newspaper. His left eye was blackened and his lip had a split in it. He sucked on the cut.

“I can see that.” Bobby took a seat at the bar. “You got water?”

“I said we’re closed.”

“You ain’t gotta open just to give me a glass of water.”

The bartender looked at him, his eyes hard, then put the paper down and went to the sink. He came back with a glass, handed it over. Bobby gulped it down. It helped, a little. His throat stopped hurting.

“Looks like someone did a number on you,” Bobby said.

“Uh-huh. Ain’t the first time.”

“Deserve it?”

“Sometimes do, sometimes don’t.”

“In this instance?”

“You tell me, asshole.”

Bobby held up his swollen right hand. “Your face did this, huh?”

“Yeah.”

“I was wonderin.”

“Wonder no more.”

“I don’t remember.”

“No one does.”

“Guess I should apologise.”

“Save it. I don’t give a shit.”

“So what happened after?”

“Couple of the boys threw you out.”

“I appreciate not receiving a beating.”

“There’s time yet.”

“Sure. Well. Thanks for the water.” Bobby turned.

The bartender called to him. “You brought somethin in with you.”

“What’s that?”

The bartender reached under the counter, produced a gun. He put it flat on the bar. Bobby looked at it.

“You threatening me?”

“No. It’s yours. You came in here waving it round. I took it off you. That’s when you started throwing fists.”

Bobby stared at the gun. “That ain’t mine.”

“You brought it in.”

“I don’t own a gun.”

“You did last night, and you do now.”

“I don’t want it.”

“It ain’t staying here. Just take the fucking gun.”

Bobby reached out, picked it up. It was heavy. “What am I supposed to do with this?”

“Stick it up your ass. I don’t care. Now get the fuck outta here.”

Bobby checked the safety was on, then tucked the gun into his waistband and went back out to his truck. The night before was a blur. He’d gone out in the early afternoon with his father-in-law, to celebrate the old man’s birthday. Somewhere along the way he’d lost him, but he didn’t know when or where. He reached into the glove box, pulled out his phone. There were more than a dozen missed calls from Karen, his wife. She wasn’t going to be happy. He braced himself, rang her back.

“Where you at?”

“Hey, you.”

“Goddamn it, Bobby! You know how many times I called you? Where you at?”

“I’m on my way home.”

“Uh-huh. You know where my dad’s at?”

“Uh –”

“He’s at home, asshole. Why’d you take his gun?”

“His gun?”

“That’s what I said. Why’d you take it?”

Bobby could feel it, pressing cool against his stomach. “I – I don’t know. I mean, why’d he have it out?”

“How drunk did you get?”

“Pretty drunk.”

“And you were driving. You’re in the truck. You know how dangerous that is, Bobby? You could’ve got yourself killed! You could’ve killed someone else!”

“Yeah, okay, but I haven’t.”

“That doesn’t make it all right.”

“Tell me about the gun, Karen.”

“You don’t remember?”

“No.”

“Well. Dad said the two of you got drunk, then you went back to his place and you got this idea in your head to go out back and shoot bottles in the moonlight.”

“Bullshit. I’ve never taken a notion to play with his gun ever before, why’d I start now? I reckon he’s just blamin me, it’s him, he’d’ve wanted to do that kinda thing.”

“You remember that?”

“No.”

“Well, he said you were real insistent on it. And I believe him, because once you’ve had a drink, you get somethin in your head – I know you, Bobby. Anyway, regardless, the two of you went out there, he left you with the gun while he goes and sets up the bottles on the fence posts, then he turns back and sees you running off. Why’d you run?”

“I got no idea.”

“Have you got the gun?”

“Yeah, I got it.”

“Just come home, Bobby. You can apologise to dad later.”

“Sure. Yeah. Sure. I’m on my way.”

He pulled out of the parking lot and headed onto the road. In the mirror he saw a couple of the bikers begin to rouse, stretch their limbs and climb onto their bikes, or off their bikes, depending on where they had woken. One of them stood to the side and pissed into the dead grass.

Bobby drove, still thirsty. His throat burned again and swallowing just made it worse. He thought about the night before, of the story Karen had relayed to him, but he remembered none of it. The mental images it conjured, however, brought a smile to his face. He chuckled.

He passed through a thick gathering of trees that sprouted up in the fields on either side of the road. Coming out from their shade, something caught his eye. A fire. There were kids stood around it. He slowed. The fire was raging, it kicked and thrashed. He stopped. It was a horse. The kids, five of them, stood and watched.

He jumped out the truck. “Hey!”

The kids looked up, saw him. They turned and ran. Bobby hurried after them into the field, then stopped. The horse screamed. It was the most awful sound he’d ever heard. He smelled burning flesh and gasoline. He looked at the horse, the heat bringing tears to his eyes. Its own eyes were gone and its lips had burned back to reveal gnashing teeth and a lolling tongue. Its legs were broken, all four of them. They’d been smashed so it couldn’t run, probably with a hammer.

It continued to thrash, to scream. It pierced his ears, made his skin prickle and his teeth grind. He tried to block the sound with his hands but it came through. He was about to start screaming himself when he felt the gun still in his waistband. He pulled it out, shot the horse until it was dead.

Lowering the gun, he breathed heavily and watched it burn. Tears ran down his cheeks. There was movement to his right. He glanced. A kid stood beside him, red-haired and heavily freckled, wearing shorts and a grass-stained t-shirt. The kid didn’t looked back at him. He stared at the horse. His mouth was twisted.

“Were you with them what done this?” Bobby said.

The kid nodded, once, very solemn. “I was with them,” he said. “But I’m not one of them.”

Bobby nodded, then turned back to the fire. The horse was just meat now. The flames were dying across its blackened corpse.

“Why’d they do it?” Bobby said.

“Because they had gas, and matches, and a hammer, and they wanted to watch it burn. It was an old horse, anyhow.”

“That don’t make it all right.”

“I know it don’t. What you gonna do about it, mister?” the kid said. “You gonna go after them?”

Bobby realised the gun was still in his hand. “No,” he said. He wiped the tears from his face, and they stood together in silence and watched until the flames were gone, and smoke rose and curled from the charred and blackened carcass.

Paul Heatley’s stories have appeared online and in print for a variety of publications including Thuglit, Spelk, HandJob Zine, Crime Syndicate, Plots With Guns, and Shotgun Honey, among others. He has six novellas available for Kindle from Amazon. He lives in the north east of England.

Paul Heatley’s stories have appeared online and in print for a variety of publications including Thuglit, Spelk, HandJob Zine, Crime Syndicate, Plots With Guns, and Shotgun Honey, among others. He has six novellas available for Kindle from Amazon. He lives in the north east of England.

Fried Chicken and Coffee

- Rusty Barnes's profile

- 227 followers