Rusty Barnes's Blog: Fried Chicken and Coffee, page 25

December 8, 2012

The Stonekings, fiction by Willi Goehring

Once, when I was naked, running around in the woods, I could have sworn I saw an old friend I used to play fiddle with. He'd been out there for months, the way I saw him, and had only the smallest notion that he'd been anywhere at all; covered in mud, naked too, and playing an instrument made out of sticks and half a log he'd gnawed into a bow of his own long hair. He ground his teeth at me and hissed like a snake, and I spent the next few minutes trying to convince him to play me a tune we used to pick called "Who Shit in Grandpa's Hat." "I'll dance," I kept telling him, laughing, but he responded by hissing and jerking his hair across the thing, batting it like that was a small curse budging me away, lifting his foot to do a big stomp like at the end of a deadly contra. Our encounter was prolonged but eventually I backed away, cautious that he might come at me with his long fingers or begin to play a whirlwind dance.

This was Old Pete, husband to Old Melinda, who played in the Ozarks' big expanse maybe two hundred tunes by ear and by memory, some said three hundred. They learned from the Stonekings, Lee and Buck and Whirly, down near Osage County, and used to put their big rafts into the White River for god knows what reason and just float in the sunshine. They grew carrots that came out purple instead of orange and knew the kinds of mushrooms that you could eat and which ones were magic. They had a chicken with three eyes they named Cooter who they shot instead of wringing its neck when the time came. Melinda wasn't quite blind, but used to tell us that when she looked at people their eyes were big black pits and their mouths looked like gaping assholes. "Purty close," Pete would say.

When I got back to my camp I put on some clothes and Noel was sitting there, still naked, long penis dangling obtrusively close to the only warm part of our tiny fire. I'd used my keys as a rattle and we'd done some dancing, and then found a few sticks that we admired. When I ran off, Pete emerged as if from the grave, but why did he refuse over and over? It was a fight, but what the hell he was doing, what tunes he was playing, where are they from, where did he learn them? In this thought I recalled I'd brought my own violin, and took care to play as sorrowful of an air as I knew at the fire, but then the fire went out, and I had no way to see my fingers, so it was as if I had no fingers at all. Noel and his knife-like penis disappeared, probably in disgust.

Melinda died while we were playing once on Old Pete's porch, the summer of 1995. We'd just come from the caves nearby on a backpacking trip, and were sore and all worn out. Melinda had been drinking moonshine and fell flat down on her own still, and I guess the pressure from all of her weight caused the still to rupture and blow. A bit of glass got lodged in her throat and she went into the bedroom and fell down with the cordless phone in her hand and bled out before we'd finished playing "Four and Twenty Blackbirds", a tune that Pete beat out so fast and with so much sliding and embellishment we sat on the roots and tried hard to follow. Somewhere there was an extra measure, a floating note, out of time, a swagger or a hold he made up or fucked his way through, but we could never find it. When we heard the tiny explosion faintly on our stumps, we figured it was just Melinda letting the pressure out of the still to speed up the binge, but when we came to shine ourselves, we saw a trail of blood leading to their pull-out bed, barely big enough for her. She'd shattered some things in either desperation or frustration. Her hair was tangled. 9–1-1 was on the line saying "Is someone there?" and "is someone there?" and "your number's not registered. Where are you located?"

At the funeral, if you can call it that, Pete lit her on fire with ethanol after a real preacher had come over to do some protestant things with the body, talk at it and talk to Pete. He left us the hell alone but we tried to listen. A bunch of relatives had come up from Springfield but we didn't know them and they didn't know us, and they had big belt buckles and very combed hair. The state was supposed to handle the body and she was supposed to get a death certificate, but if Pete kept her alive we figured he'd keep getting her welfare for at least a little. Before night fell we chopped a bunch of wood for him and left a bottle of whiskey under the moonlight by the well. He'd see it when he'd come-to and went to take a piss in the morning.

But now it was completely dark, and there was no whiskey to console anyone over their losses. I started to want to go uphill to try to find some moonlight, but I was scared because then I'd never find our camp again. I checked my phone– it was all but dead, and Noel didn't have his up his ass probably. There was always 9–1-1 if something bad happened, I've always told myself. Chances were nothing would happen at all.

Of all the tunes she could've exploded the still during, "Four and Twenty Blackbirds Dancing on a Fawn Skin" as likely as any, but not likely at all. Every tune name comes somewhere out of the dark recesses of either memory, learnt from the Stonekings or the Leonards or Emmett or Possum, or some cruelly made-up joke. Some of the tunes go by a dozen different names. Some of them are made up by the person who has no idea what they're playing in a sort of good-ol-boy joke. Pete used to do this, gesturing wildly with his bow over his pigeon toes. Sometimes he would fuck with us for hours only to tell us he'd made a story or a tune up. Sometimes a whole conversation would be a big lie with a dirty joke at the end. Sometimes he'd just show us where the horse bit us, smacking our balls.

I realized suddenly, walking up that hill, that "Who Shit in Grandpa's Hat" is more of a ditty than a tune, and I don't know if Pete learned it from the Stonekings or made it up by his lonesome. It's not that catchy, and you couldn't dance to it, and it isn't very long. "Who did it", it goes, "Who did it," and then "Who dida shit in grandpa's hat?" I wouldn't dare to sing it unless I was someplace less than alone, entertaining people or trying to be funny. A minor provocation for vulgarity's sake. That kind of thing. No wonder Pete was pissed I asked for it. Suddenly I was worried about Noel. He liked to hang himself a bit, or choke himself to feel high, and in the woods it was possible I'd find him scrunched and pruny in the sogged-up morning in some ditch with a vine around his neck, horny Old Melinda messing with him. That would be serious among all this foolishness. That would ruin everything like an exploding still and the groundward march of an old house.

But I went uphill anyways, towards the moon, not full, not even half-not dark, peeking through the discernible ring of light it made at the edges of its pit. I breathed heavily and almost sang, but waited till I reached the peak, sodden-crotched, where maybe I could see an amenable highway light. But this is not like any other place where the highways are everywhere, not like the cornfields where the cell-phone towers blink like elephant skeletons. Here you go up one hill and you're gone for good in their muddle, and god isn't even looking for you because he knows you're already knee-deep up in it and you will either turn up somehow or you wont. "Who gives a shit," Pete would say, when we asked him almost anything.

Suddenly I remembered a dream that I'd had a long time ago while looking at the overcast sky, the hills in the distance invisibly black. I took my pants off and ran my ass across the grass to itch it. In the dream I was in a cave alone with no escape, and there was a massive pool of water trembling on the floor. A great whale emerged, breaching the water and filling the cave with such an enormous sound the whole place rattled and shook, and I had a fiddle in my hand and was playing it on my chest and singing the same note with the whale. I started to cry and the whale leapt up again and again in a massive duet. I sobbed and sobbed. When I woke I was late to where I was going, and couldn't even shave.

When I remembered this I wished it had been perfect to sing out again, as if the hills were whales, as if Pete was out there to teach me about what life is, about things that matter or at least pretend to matter. But these things weren't true. If I couldn't see, I could sing out and listen for the echo to return and give me a place, but, goddamn it, I wasn't lost, and maybe I never would be. I could hum a nameless tune in the dark if it would comfort me, and the joke might be remembered, even written down in the light of day. I'd come down going uphill, and every piece of reveling left in me was expended in being imperfect in that moment. Will I remember all the times I remembered a bunch of bullshit I desperately wanted to mean something? I'd rather listen to the air, I think, if the air could ever be like Pete's interminable squawk. But ah, Pete is probably dead, in his grave with all those tunes. I think that's all right. Soon I will be too.

Willi Goehring is a midwestern poet and banjoist pursing an MFA at the University of Arkansas, where he is a Walton Fellow. He enjoys studying folklore and teaching English almost as much as he enjoys homemade wine and square dances.

Willi Goehring is a midwestern poet and banjoist pursing an MFA at the University of Arkansas, where he is a Walton Fellow. He enjoys studying folklore and teaching English almost as much as he enjoys homemade wine and square dances.

November 13, 2012

Redneck Raindance by Willie Smith

It threatened rain,

so I got out my gun, got in the car

and gunned it on down to the graveyard,

where it was dark and nobody would know,

but I knew the clouds would see clear.

I got out and got my gun out,

fired myriad rounds at the atmosphere

and gunned down the clouds.

Fog fell in patches, then cleared.

I got my gun down,

headed for the car;

overhead stars started to appear

and I again began to breathe in fear.

The more fired at, the more the stars broke out.

I shot more and more flared up. I shot up

the sky, then drove home, sad as hell.

Shot the dog, shot the wife, shot my Playboys;

finally reloaded and waited for the sirens,

that never came. It began to rain.

I got in the car, backed out over the dog,

laid a patch on the wife’s ass,

got going real good and

gunned it on down to the graveyard,

where it was dark and nobody would know,

but I knew the clouds would see clear.

Willie Smith is deeply ashamed of being human. His work celebrates this horror. His story anthology NOTHING DOING is here: http://www.amazon.com/Nothing-Doing-W... .

November 6, 2012

Sparks on the Turnaround, fiction by Marsha Mathews

With her hands clapped over her ears, Birdie Dee tried to read Hobart’s lips. Thick and pink, they curled and stretched, puckered and parted. But she couldn’t figure if he was complimenting her or cussing her. All she could hear was the roar of stock cars – red, blue, green, some with Tide boxes, m&ms, or other graphics. She nodded like she understood so he’d quit bugging her. Besides, not hearing him suited her just fine. Hadn’t he said his fill at supper? Hadn’t he and his mama said enough, giving their two cents plus about abortions and the wayward girls that had them?

Hobart’s leg brushed hers, so she inched away. Behind sparse black hairs, his neck blotched red. He gulped air, then belched. The air smelled like dead fish.

“Jeeze.” Birdie Dee stood, shook out her yellow slicker, moved down the bleacher a bit, away from him. Because there was always mist in the Southwest Virginia air, she took it almost everywhere. Now it came in handy again, saving her butt from tobacco spit, gum, spilled soft drinks, or any other nasty thing that might be on a bleacher.

Hobart turned back to the race. She liked Hobart; his mama, Imogene, too. Even if she did act like she owned the church and had a lock on everything right. Now, Hobart, well, she could imagine him lifting the “WE KILL BABIES” signs from the truck and propping them in front of abortion clinics, Imogene with arms crossed over her enormous bosom, directing him.

“Birdie Dee, want a Coke?”

“What?” she yelled, over the speeding cars.

“Want a Coke?” He made a chug-a-lug gesture.

Before she could answer, he pulled a fiver out of his wallet and waved it. The vendor strutted up the steps, a tray of drinks strapped to his neck.

“Hey. Over here.” Hobart held up two fingers. “Two Cokes.” He looked at Birdie Dee. “Careful, loose lid,” Hobart shouted. He handed one to her. The cars squealed past.

“Thanks.”

Hobart jumped to his feet. “Yeah, buddy,” he bellowed from deep within his throat. “Yippee-yipee-yi-yi!” The Hooter’s car whirled around the track.

People turned to look at Hobart, and Birdie Dee felt her face flush. They think we’re together, she thought. Me and this guy who’s Mom’s age and about as classy as a dump truck.

When she agreed to come with Hobart to the races, she assumed Imogene was coming, too. They’d stuffed themselves like ticks with her country ham, fresh corn, fried okra, and sweet potato casserole, not to mention butter biscuits and what Imogene called her berry-D-licious pie.

After eating, Birdie Dee took a walk along the gravel road that curled around the boulders and ridges. She needed a break from Hobart’s inviting glances; and now, the added pressure of those fool signs. She came across them when she stepped out to the carport for a smoke. They said, “WE KILL BABIES,” not the kind of thing you’d expect in an old lady’s garage. Birdie Dee needed time to think, to shake off dinner, their talk, the truth according to Imogene-Knows-Everything. So she took off running, and once Hobart ran out of wind and turned back, she eased into a quick, deliberate stride.

In the dusk, the view was one not easily forgotten, a feathery pink and violet sky, and if she could just climb about thirty yards or so, she would be able to see the full sash of Coeburn’s twinkling lights curving around the mountain like glittery wool tossed around someone’s neck. She swerved away from the road, and clutching some ropey twigs, she pressed through the scratchy brush, found footholds, and began to climb.

From a jutting rock, she looked out over the hollow. Imogene’s roof had not one cat, but four, all curled near the chimney of the wood stove. And there was Hobart, taking the porch steps, two at a time.

Birdie Dee climbed higher, taking her time, moving up the mountain the way Grandfather Laughing Horse once showed her, not shifting her weight until her toe was lodged.

After what seemed a few seconds, a gunshot! Her foot slipped. She rolled. Down she slid through briars; rolled, bounced rock, rolled. Thirty feet later, she cried out for him. “Hobart!”

Embarrassed, she lay on a ridge not ten feet from the dirt road. Criminy! She thought. Somebody shooting? A hunter? She lifted her head but saw only fetterbushes. Surely, Hobart was too far to hear her. Yet, in the mountains, sound carried, as it would over a lake. The last thing she wanted was for Hobart to hear her cry for him, but in her moment of fear, that’s what she’d done, and she couldn’t pull it back.

She waited for the dust to stop swirling. Just enough light, she could see coal flecks settle on twigs, the yellow dirt. She smelled ramps and stifled a cough, her breaths drawn and raspy from her tumble. Unleashed, gravel continued to slip, crackling. She lay, unmoving. Hobart’s truck rumbled toward her.

“Holy Jesus on a mountain,” he said, jumping out. “You okay?”

“I heard a gunshot.”

“Ain’t no never mind, just me. I lost sight of you. I wanted to wave you back.”

She felt a jabbing pain in her leg when she tried to put weight on it but refused his hand, fell back against the slope. “Ouch!”

“Good thing for you, Mama’s a nurse. Well, an aide. Used to be, anyhow, in her heyday. Don’t fret. She’ll fix you up good so we can go to the races.”

“The races?”

“Sure, hear that?” He paused, looked across the hollow. “It’s them, doing the practice rounds. That’s why I come up from Bryson City. There’s a special contest tonight where you can win a drive around the track. And I aim to win it.”

“You serious?”

“Yeah, buddy. Mama thinks I come up to fix her washer, but this contest, this shot’s only once a year.”

“And me? What about me? I might get to drive a race car?”

Birdie Dee didn’t see it coming. She felt his hands slide beneath her. He swooped her up. She was in the air, in his arms, against his chest.

“Dern tooting. You know how it is today, women get equal footing.”

She smelled something. Shoe polish? He reeked of it.

He pulled her closer. Every nerve in her body stood up inside her and poked her from the inside. “Crap, Hobart. Put me down.”

“Look, do you want to go to the races or not?”

“Okay, okay. I’ll go.” His skin, dark behind his sideburns, a silver hair flagging her, she realized he had colored his temple hair with brown shoe polish. Gross, she thought. “But put me down. I’ll go, already.”

Birdie Dee pounded on Hobart’s chest. She pounded and spat every mean word she could think of: “You ten-ton tub of lard,” the whole way down the mountain to his 4 X 4.

That’s how she ended up at the races. But it was just the two of them, without Mama. To make things worse, Hobart had insisted on paying her way in, like it was a date or something. Birdie Dee pulled out her money, but Hobart pushed it back into her bag. Guys always the big shots, she thought. Throwing money around. Birdie Dee sipped her Coke. She didn’t even like Coke. She liked Sprite, but he didn’t bother to ask.

At least she was right where she always dreamed of being — at the stock car races. Her Dad had told her girls didn’t belong in such places. “But look at me now,” she thought. To her, just being in a place Dad said was off limits was reason to be there. With the noise and the smoke and the fiery smells, Birdie Dee came alive.

“I’m having fun.” Birdie Dee stretched her arms into the air. “Holy crap. I’m having fun,” she shouted to the whir of the tires. Her mom kept prodding her to go somewhere, somewhere cool. She couldn’t wait to tell her.

This was so much better than sitting in her little room above the video store where she worked, making sculptures out of packing material. She had just as much chance as anyone there to win that raffle. Birdie Dee imagined herself strapped into the low seat of a stock car, pushing the throttle – whoosh!

“Trouble.” The loudspeaker crackled. “Trouble on the second turn.”

The Downy car spun twice. It backed into the wall.

Everyone jumped up.

“He okay?” Birdie Dee inched closer to Hobart.

Hobart didn’t answer. Smoke gushed from the engine.

“Can he get out?” Birdie Dee grabbed Hobart’s arm. He stood stiller than a turtle on a log. Wasn’t he aware of her touch? Or had fear sucked his feelings into his boots?

When had the mountains on the far side of the track darkened to a silhouette? High Knob now looked like cardboard against the ash sky. The crash caused fuzziness inside Birdie Dee’s head.

The car door popped open.

The driver staggered out.

“Phew!” Birdie Dee bent over to tuck her cup underneath her seat. She counted to ten, sat up.

Hobart’s mouth moved, but his words weren’t registering. His eyes wouldn’t turn her loose. She started to hear him. “When we was at Mama’s, looking at the fountain?” She nodded. She knew what he was getting at. “We was getting along pretty good, me and you. I mean, no matter how I look at it, I just don’t see why you run off like you did.”

Her face flushed, and she exhaled as she spoke, “I don’t, I was, confused.”

“About what?” Hobart looked at Birdie Dee as if trying to understand. “The abortion thing? Mama’s real set on things like that.”

“Look, Hobart. It’s not like people who have abortions want them.” “Gimme some credit. I know, I know it ain’t like running up to Wal-Mart for batteries.”

“My best friend.…” She could see her friend Angel’s eyes just after it happened, fading from gems to flat gray slate.

“I hear what you’re saying about your friend or whoever, I hear what you’re saying, and I want you to know, I ain’t Mama.”

Birdie Dee’s mind was back on ninth grade. “If my best friend Angel couldn’t have had an abortion, I believe she would’ve dug the fetus out with her fingernails.”

Hobart’s eyes dipped like fishing sinkers.

“A big guy holds a stinking fishing knife to you as he, you know.” She coughed.

“Disgusting.” His eyes flamed.

She gulped and cleared her throat. Her face burned.

“Are you all right?” Hobart reached over to pat her back.

She spread out her hands. “I’m okay, I’m okay. But it’s more than that. It tore Angel up.I mean, it tore her up.”

“They’ll get him.”

“Physically, mentally, every way.” Beads of sweat formed on Hobart’s forehead. His words were measured, but kind. “He’ll strike again, that snake. And they’ll get him. You’ll see. They’ll get him.”

Neither spoke during the next race. Afterwards, Hobart said, “I want you to know, I don’t blame you.”

Birdie Dee’s brow creased.

“Your friend, I mean. I don’t blame your friend for having the abortion. I don’t blame her one bit. I’d do the same thing.”

Jeez! She thought. He thinks it was me got raped. They sat without talking. People moved up and down the bleachers. Moths flitted about the lights. A baby whimpered. Cars positioned themselves for the next race.

Hobart raised his voice. “Case like that, hell, it’s all you can do.”

“See, Hobart, it’s not always about preventing a life. Sometimes – ”

The announcer intruded. “Sparks on the turn. Trouble. Trouble.”

The nine car, its roof painted like a Tide box, trailed gray smoke.

“Sometimes it’s about preventing a—an—explosion.” Birdie Dee jumped to her feet along with everyone else. The car spun twice, knocked three other cars that, in turn, hit two more. Smoke licked the left front fender. The door flung open.

“The driver is still strapped in,” the announcer said. “Smoke’s pouring from his radiator.”

“He’ll burn up,” Birdie Dee cried.

Hobart smiled, and his cheeks balled.

“He’ll burn up.” She trembled.

“Sure pumps your blood, don’t it?” She wanted to smack him. He was getting off from the poor guy’s pain. She stood, nibbling on her thumbnail.

The audience whistled and stomped as the final race roared.

Stock cars, one after the other, shot across the finish line and then taxied off to the pit. News cameras converged as the winner, Spud Neece, said a few words: “Did what I could … lay in there real nice … had a great run.” From Miss Lonesome Pine, he accepted a trophy and a kiss before strutting off with a wave and a grin.

“Folks?” the announcer said. A hush fell over the stands. “It’s time for — ” Cheers shot up from the crowd. “You all sound ready for this.” The crowd hooted and stomped.

“Yeah, buddy,” Hobart yelled. “Yeah, buddy. You got that right. Yoooo-heee.” He grabbed Birdie Dee’s hand.

The sound system whistled. The announcer’s voice broke in and out of the high-pitched squeal, but his message was clear: “Time for the Grand Drawing.”

The sky was so dark now, the mountains had vanished. Halos glowed about the lights. Miss Lonesome Pine’s tiara sparkled. Hobart let go of Birdie Dee, smacked his hands together. “This is it, this is it,” he said.

From the loudspeaker: “One of you is about to win a ride of a lifetime.” Birdie Dee held her breath. The beauty queen dipped her hand into the golden cup, drew the winning ticket. Except for a few coughs and a baby’s babble, not a sound from the crowd. What would it be like to be Miss Lonesome Pine and to hold someone’s dream in your hand? Birdie Dee wondered.

Hobart grabbed Birdie Dee’s hand and squeezed.

“8931,” Miss Lonesome Pine said. Her voice twanged.

Hobart drew in a breath. “8931?” “Yep.” Birdie Dee wondered at the light in his eyes.

“8931?” His voice was sandy. “You’re sure?” She nodded, and vertebrae popped in her neck.

He pulled out his wallet, flipped it open. “Positive?”

Her lips parted. “8931.”

“8931,” said the announcer. The microphone blared. “Will the owner of ticket 8931, please come forward?” He stepped away from the mike, but everyone could hear him say to Miss Lonesome Pine, “What the yokels is taking so dang long?”

Birdie Dee’s eyes hung onto Hobart’s wallet. He removed a ticket from the right side. His ticket. Yours is on the left, he had said earlier. He’s just playing, she thought. He doesn’t fool me. If he really won, he’d be jumping out of his seat like a crazy person. She could stand it no longer. “Did you win?”

“No,” he said, handing her the ticket. Her heart felt as if it had been kicked.

“You did.”

"What? No way.”

“Yes way.” Her hand trembling, she inspected the numbers: 8931. “Oh, my god.” Adrenalin surged. “For real?” Hobart’s face beamed. “You serious?”

His eyes shuffled joy.

“8931,” the announcer said. “Last call for 8931. Does anyone here have ticket stub number 8931?” Birdie Dee jumped to her feet. “Here,” she screamed. She hobbled down the steps. “Here!” When she reached the gate, she turned, looked at Hobart. His ticket was on the right, not hers. This was his dream, and she was no dream stealer. She took a few steps back to him.

“No! Go on with you.” He signaled with his hand.

Do I dare? She smiled and then hobbled the rest of the way, through the gate, and across the track, her legs aching from her fall down the mountain. She breathed deep the scent, gasoline and pine. She held the ticket in the air, Hobart’s ticket, the ticket of the guy who might not be such a bad do, after all. And for tonight, at least, her father’s face and the cutting sorrow of abortion buried in her back pocket.

Marsha Mathews teaches Creative Writing and Appalachian Literature and other interesting courses at Dalton State College, in Dalton, GA. Her most recent poetry chapbook, Hallelujah Voices, presents a Southwest Virginia congregation as they experience pivotal moments and also deal with their new “lady” preacher. Marsha’s novel excerpt “More than a Mess of Greens” was a finalist for the 2012 Rash Awards and appears in The Broad River Review. “Sparks on the Turnaround” was presented to a chuckling audience at the Southern Women Writers Conference at Berry College in September. The story is also a modified segment of her novel-in-progress A Secret to Kill For, which she one day hopes to sell like crazy.

Marsha Mathews teaches Creative Writing and Appalachian Literature and other interesting courses at Dalton State College, in Dalton, GA. Her most recent poetry chapbook, Hallelujah Voices, presents a Southwest Virginia congregation as they experience pivotal moments and also deal with their new “lady” preacher. Marsha’s novel excerpt “More than a Mess of Greens” was a finalist for the 2012 Rash Awards and appears in The Broad River Review. “Sparks on the Turnaround” was presented to a chuckling audience at the Southern Women Writers Conference at Berry College in September. The story is also a modified segment of her novel-in-progress A Secret to Kill For, which she one day hopes to sell like crazy.

November 3, 2012

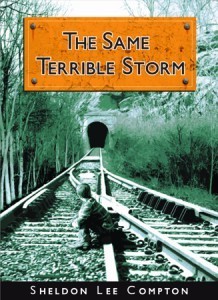

Sheldon Compton's The Same Terrible Storm

One of the ways I judge my fiction is by its relative veracity. It bugs the hell out of me when writers get easy things wrong: gun details, car details, wildlife, you name it. In Sheldon Compton's The Same Terrible Storm is that there's never a misstep, never even an implicit hesitation. With all the details in place, the stories have room for language, plot, and characters to move in ways unusual and fine.

One of the ways I judge my fiction is by its relative veracity. It bugs the hell out of me when writers get easy things wrong: gun details, car details, wildlife, you name it. In Sheldon Compton's The Same Terrible Storm is that there's never a misstep, never even an implicit hesitation. With all the details in place, the stories have room for language, plot, and characters to move in ways unusual and fine.

Take "First Timers," for instance, a short and sharp piece from the book's middle.

The guy behind us, standing with Josh, looks like he just walked out of a tree and turned to rock. It's Hank, Amy's dad. I figure if he stood by the fence and the pen, he'd blend into the wood (56).

Quietly, these few words do a great deal of work for the story. The story begins with a few young men (I'm guessing late adolescence, since it's not made explicit) speeding down a road while hung over, it's the appropriate place for the young ones to begin to get their comeuppance. It's safe to say none of them would look as if they'd walked out of a tree and turned to rock; they won't be threatening Hank for primacy.

The two brief scenes in the full story highlight the difference between the narrator and his buddies. They play at being hardasses by drinking and thinking, more or less. Josh is "soft as a couch cushion" compared with Hank, even as he holds a shotgun and shells in readiness to do the pig in. Almost needless to say, Josh can't do it, and the plot turns to Hank and our surety that he will be able.

Compton's skill in bringing life to characters via the small and telling detail is superb. In nearly every story here, no matter the mode, third person, first person, omniscient or not, the plot rises and falls from those character details, and not by the engine of a cockamamie tacked-on plot.

Sheldon's a friend of mine, so in the end this is an appreciation really, not a review. I am positively giddy to see what he can do within the context of a novel, which I know will come sooner than later. This is an excellent collection, though, worth your time and hard-earned money. Send me a message at proprietor@friedchickenandcoffee.com with The Same Terrible Storm in the subject line, and I'll send the first two people who respond a copy of the book for their very own.

November 2, 2012

I INHERITED A MIXED ANIMAL FROM UNCLE LIVING IN WOODS, novel excerpt from Richard Martin

“There is one small movement of the story that eludes your control,that you cannot even see, one alien thing with no purpose other than to teachyou that in the darkest corner of the story dwells a wild force that is too much a part of you to see, a blind spot, just as you do not see your own eyes as they sweep the woods you walk through for danger.”

—Wilbur Daniel Steele

1.

My Uncle Leonard was a hermit who lived alone in the Unconscious Forest his entire life. Unc had a sack of money stashed away, and when he went to meet his Maker he left every penny to my little sister Shane. He left me, a full grown man, a rusty bicycle and a busted set of drums. I don’t mean he left me a full grown man, I mean I am a full grown man. So why would he leave me a load of childish junk instead of cold hard adult cash?

He also left me some kind of a mixed animal, which from the very beginning would turn out to be even more questionable than the junk.

*

It was the middle of the night two moons ago when the beast found its way to me here in Hmm. Uncle Leonard’s woodsman neighbor Chuck woke me and Shane pounding our cottage door with the coconut knocker. Chuck was a stalwart, self-reliant, phonebooth-size fellow in mud-plastered boots and a checkerboard greatcoat, but that night a royal case of the heebie geebies had ahold of him.

He had drove four hours from the Unconscious Forest to deliver the news of Uncle Leonard’s passing, along with the cash for Shane, and the bike, drums, and critter for me. He drug the goods in and started back out as if a ghost was after him, but Shane blocked the door in her “Mayor of All I Survey” nightshirt. We managed to calm the big chap down and reel a few rambling incomprehensible facts out of him, first off how Unc had demised.

“Sudden natural causes,” says Chuck, panting. “Weren’t present. Had to take Doc’s word. That there—” (indicating the animal, who stood motionless and undescribable in the corner, fur bristling and eyes ablaze) “—is Leonard’s only living proof that survived the fire and explosion.”

“Fire and explosion?” Shane says.

“Yes, ma’am. Your Unc turned hisself into one wild ‘sperimenter out there.” Sweating and twitching, Chuck glanced at the animal which in turn latched its gleer onto me. “His death-bed wish was me to brang you these gadgets. ‘Them kids, Shane and Lemuel, my bonehead blood,’ your Unc called you, with affection. I done as he ast, laid him to rest on the bluff he daydreamed under the Lights at. Then I nursed that gasly thingum back to health. Oh!” He reached in his greatcoat and set a small burlap package on the coffee table. “That there’s a poultice for the stitches.” He run a finger along his ribs area. “Good luck!” Chuck elbowed through us and out the door.

“What’s its name!” I holler, and Shane lets out, “What is it!” but Chuck peeled out of the village in his Helms van, leaving us to our minor grief and major bafflement.

We lain our eyes upon the creature that stood with bad intentions blazing from the corner. Size-wise, it was near to a long large turkey, a smaller wart hog, or about one and two-thirds emperor penguins.

“Inpossible,” I say. We gandered at it from different angles. It did something to your deductive faculty. “What and the world was Unc up to out there?”

“No good. No good at all.”

“It don’t look too tamed,” I say.

“I agree. It has retained a portion of its wildness.”

“What do you figure kind of a animal it might be?”

“Contradictory. That part resembles mutt,” Shane says, pointing from afar, “but that calls cat to mind.”

“I’d say you got you some pig right there, maybe a dab of goat up around here.”

The thing was, the parts blended together so seamless you couldn’t pin down where one left off and the next begun.

“Would you say a little monkey perhaps?”

“Lots. But possum along there.”

“Some fox up on top, maybe sloth through here, pinch of wolverine across there?”

Shane and I shook our heads in unbelief, but there the thing was, shaking its head in unbelief right back. Both it and we appeared no happier than any of the others to be seeing what they saw.

At that the animal gave the lowest growl that ever been growled. My footbones felt it through the floorboards.

“So, Unc’s gone on,” I say, hoping the varmint would appreciate a change of subject from itself. “Poor old Uncle Leonard.”

“Oh, fiddlesticks,” says Shane. “He was mean and lowdown and loved it. We couldn’t stand him and he couldn’t stand us more.”

“Well, you ought to respect the dead, even if you hated their guts.”

“I respect the dead’s legal tender,” she says, scooping up her new found cash and flouncing back to her room as if our life had not just took a bad fork forevermore.

I sat in my rocker and commenced to to in fro reassuring and calm, keeping one eyeball on the sole remaining consequence of whatever Unc’s lurid business had been out in them woods. It kept both eyeballs on me back. “You could sit down if you want,” I say. It declined with a snort. To act normal, I took a whiff of the burlap package Chuck gave me and that stinkbomb knocked my olfactories back to Independence Day. I was not keen to slap no poultice on that thing’s undercarriage. “I wonder why you went and got yourself stitches,” I mummer.

From the shadows it glowered at me like I personally flang it out of the Garden of Eden. “Don’t blame me, fella,” I say. “I’m only a link in some spooky chain.” But then I reckoned, why should I care what it thought? Was I my dead Uncle’s mystery animal’s keeper? It looked like I was, for a nonce, but I didn’t got to like it, did I.

Richard Martin lives with his beloveds on a land-locked island near Los Angeles. This piece is the first chapter from his spiritual comic novel of the same name, which, in case you forgot, is I Inherited a Mixed Animal from Uncle Living in Woods. Another novel, Oranges for Magellan, about a flagpole-sitter and his family, is making the rounds, and a third, a literary romantic ghost story, is this close to getting itself finished. His work has appeared in Virginia Quarterly Review, North American Review, Chicago Review and Night Train. The last book he read was Herman Hesse’s Knulp, which he is now reportedly mulling. His unreliable blog is at http://mixedanimal.blogspot.com/.

Richard Martin lives with his beloveds on a land-locked island near Los Angeles. This piece is the first chapter from his spiritual comic novel of the same name, which, in case you forgot, is I Inherited a Mixed Animal from Uncle Living in Woods. Another novel, Oranges for Magellan, about a flagpole-sitter and his family, is making the rounds, and a third, a literary romantic ghost story, is this close to getting itself finished. His work has appeared in Virginia Quarterly Review, North American Review, Chicago Review and Night Train. The last book he read was Herman Hesse’s Knulp, which he is now reportedly mulling. His unreliable blog is at http://mixedanimal.blogspot.com/.

October 30, 2012

Sevier Juvenile,fiction by Matthew Funk

Andy kept knocking his head against the wall. Everybody in the courthouse lobby just watched. Some held hushed conversation, stared down the clock, pumped their leg.

Jolene scooted away from the damp slap of the boy beating his simple head against the cream-painted brick. She crossed her Vans near the spread of Gary’s Nike high-tops. He sat straight as his hair-cut but his eyes dived for the floor whenever nobody saw them.

“You here for the thing at school?” Jolene said.

Gary glanced at her. “Bomb threat? Yeah.”

“That’s pretty serious, huh?”

His broadening shoulders hiked. “I ain’t guilty. Got put up to it. School’ll probably drop charges. What’re you here for?”

Jolene pursed her glossed lips, cooking up an answer that tasted better than the truth. Andy’s dad, Harlan, nearly stepped on her feet storming by. Harlan cradled the boy’s head.

“Hey, Andy,” Harlan said in a lullaby tone, “it’s all right. Easy there.”

“I want to go home, Dad,” Andy said, eyes dull under heavy lids.

Jolene and Gary waited, their silent mothers flanking them like graveyard angels, for Harlan’s reply. Harlan just pet his son’s oversized head and turned his worried face away. A court clerk waddled out of Hearing Room 201 to call the next docket.

Jolene started to stand. Her mother stayed her with a touch.

“Not us yet, honey,” she said. Jolene didn’t have time to relax before her mother’s next words made her tense as a coon trap. “Besides, when it comes time, you won’t be expected to speak.”

Jolene twisted her face back to Gary, to hide the look of shock and protest on it. Gary was staring at the hearing room. In its doorway, an officer stood, all meat-red size under a razorback haircut.

“Ain’t that Officer McMahan?” Jolene said to Gary.

Gary’s features answered, quiet and sharp as a cornered animal.

#

After a half-ton boy was led from the hearing room in handcuffs, attitude angry as his acne, the lawyers arrived. It was late already, but each man acted like time was a force they were immune to.

“Nothing to worry about,” said the towering lawyer to Gary’s mother, casual as the fit of his Knoxville-tailored suit. “We’ll raise the issue of the police officer’s son, Chance, putting Gary up to the bomb threat and yet not getting punished.”

“Officer McMahan’s here, though,” Gary whispered. “He was the one who stuck it on me and let Chance go. If the school’s going to drop it, why’s he here?”

The lawyer left with barely enough time to smile.

Harlan’s lawyer sat by him, picking his blue jeans’ fray. “This ain’t the kind of charge they’ll let slip, Harlan. Your boy’s testimony could sink you.”

“How?” Harlan’s teeth worked his lip like his hands did his knees. He watched Andy beaming at the police officers lined up to speak at the hearing. “The boy’s slow. Retarded. It’s plain to see, even if it ain’t on record because I home school him.”

The lawyer shook his head as if just to see his beard sway.

“Everybody has to be on deck here,” said the beanpole boy of a lawyer to Jolene’s mother, cupping her wilted shoulder. “Speaking for Simon yourself will help. But if Jolene can speak on his behalf, that could make the difference between losing custody of him and a home arrest.”

Jolene’s mother tensed herself like a fist before laying a soft look on her daughter. “Jolene’ll speak for Simon. She knows he didn’t touch none of them kids a bad way.”

Jolene just nodded. She couldn’t raise her eyes for fear of letting her mother see what wailed, chained, within them.

The hearing room clerk called the next docket. Harlan and Andy went inside to stand before Judge Rader.

#

Jolene pumped her bare leg four hundred times, counting each, as the clock spun until the Hearing Room door opened again. Gary drank down two bottles of Powerade, the blue kind, sharing half of each with Jolene. Their mothers stared at the absences left by their lawyers as if still trying to bargain with them.

“Mr. Darius,” the clerk called. “We’re ready to here the Sumner case.”

Gary looked to his mother, already on her feet, and straightened his pressed shirt. “That’s us, Mama. Where’s Mr. Darius?”

She shook her head, mouth and eyes gaping, feasting on the crowded lobby. “Try and go find him. I’ll wait here.”

Gary bolted like he did on the field trying to avoid a sack. Jolene trotted behind.

“I’ll help you look,” she said.

He shot a look back to her, but any confident reply dried up and blew away under the hot shock on his face.

They walked the hall, flanked by cheap print-out posters of smiling families, ads for community outreach emblazoned with Sheriff badges, tacky daisy-orange flyers trumpeting the U of Tennessee Volunteers.

The end of the hall had no lawyers, only sad, fat women and the rain-frosted glass doors where jailhouse vans sat. Gary circled, darting, refusing to be still.

Jolene tapped his arm and pointed up to where the Child Services offices were.

“I’m going up there.”

“Why?” Gary asked, only glancing.

“Got someone I need to see.”

The docket was called again. Gary looked down the hall and back, and Jolene was already most of the way upstairs.

Harlan came out of the hearing room alone with his head bowed.

“I never did any of those things,” he muttered, his lawyer’s attention buried in his Rolex knock-off, deaf. “I was the best father I could be to that boy and no less.”

He turned back to Judge Rader’s chambers to watch the bailiffs cuff his son.

#

Jolene felt the scorch of her mother’s stare all the way down the hall. She unfocused her eyes, like they taught her in school to watch an eclipse, and walked into it.

Andy sat, cuffed and with his head cradled in both Harlan’s hands, beside Jolene’s mother.

“Where you been, girl?” Jolene’s mother said. Jolene just shrugged and sank down and watched the rain chase smokers making frantic phone calls outside the lobby.

“You got to go, Andy,” Harlan said, voice carefully kneading any trace of his sobs from it, refining it into something strong enough to reach his retarded boy. “I’ll visit you soon as I can.”

“Why, Pa?”

“Because you burnt up that house, boy. I tried my best. It was just one too many things for the Judge.”

“I want to stay with you, though,” Andy said, echoing it again and again as the bailiffs smirked to one another, idling away the time with a talk of college football.

The hearing room opened and Gary came out with mother and lawyer in tow. His shoulders were level but his eyes stared out as if he were laid on his back.

Darius and Gary’s mother drifted to a corner and talked—him smooth, her all anxious speed. The clerk called for Jolene’s mother.

“You coming?” Jolene’s mother asked her.

Jolene shook her head. She drifted closer to Gary, staring at his hand as if she were holding it.

“You ain’t going to say your piece for Simon?” Jolene’s mother hissed.

“I said it already,” Jolene said. She didn’t watch as her mother entered the hearing room, spine sagging more with every step.

“You get off, Gary?” Jolene asked, finding enough hope in herself for a smile.

“Nah,” Gary said. “But they didn’t convict me neither. Trial’s been postponed a third time. School won’t drop it but they won’t make a case.”

Jolene followed Gary’s stare. She saw it fracture as it met Officer McMahan’s. The School Resource Officer glared back at Gary, just to watch the quarterback’s confidence crumble. Then he went into the rain with his bailiff buddies hauling Andy away.

Gary and Jolene sank down onto the bench by Harlan. Harlan’s copper hair screened his face as he stared at his John Deere hat, working it in scarred hands.

“Been here all my life,” Harlan said to his hat. “And they take my son, just like that. Just like I was nothing.”

“How about you?” Gary said to Jolene, looking away from where Darius was trying to get his Mama to share a smile.

“How about me?”

“Did you get out of trouble?”

Jolene looked up, teeth releasing her lip as she saw the Child Services officer come from upstairs and head to join her mother in the Hearing Room. The CS woman laid a look of sympathy on Jolene, all the pity of a saint in stained glass shining on her.

Pity didn’t make Jolene feel good, but it was all she had. It straightened her up. Her hand slid within brushing distance of Gary’s. Her smile found his hardened eyes.

“For now, maybe,” she said. “For as long as you can ‘round here.”

From within the Hearing Room came her mother’s wails of loss.

Matthew C. Funk is a social media consultant, professional marketing copywriter and writing mentor. He is an editor of Needle Magazine and a staff writer for Planet Fury and Criminal Complex. Winner of the 2010 Spinetingler Award for Best Short Story on the Web, Funk has work featured at numerous sites indexed on his Web domain and printed in Needle, Grift, Pulp Modern, Pulp Ink and D*CKED.

Matthew C. Funk is a social media consultant, professional marketing copywriter and writing mentor. He is an editor of Needle Magazine and a staff writer for Planet Fury and Criminal Complex. Winner of the 2010 Spinetingler Award for Best Short Story on the Web, Funk has work featured at numerous sites indexed on his Web domain and printed in Needle, Grift, Pulp Modern, Pulp Ink and D*CKED.

October 27, 2012

Two Poems by Glenn Hollar

Bottle Rocket Ars Poetica

And if we banged

into the absurd,

we shall cover ourselves with the gold of owning nothing.

—Cesár Vallejo

I wonder if the great poets ever had this problem

I think, as a bottle rocket cuts a hole in the night

next to my right ear. Sure, Wilfred Owen

was pinned down more than once, and Pound

found his gods in the landscape outside Pisa,

but neither chose that. I step out from behind the corner

I’m using for cover, and set light to the fuse

of another scream, this one leaving a shower of sparks

as it skips off the screen door he’s hiding behind.

We’re the only people for miles.

Yeats was a dreamer and Dylan Thomas was a drunk,

but neither was this stupid. Soon, very soon, we will tire

of banging into the absurd. We’ll go back inside

to grab another beer from the Farmhouse fridge

and we will drown ourselves in gold.

I’ll leave it for tomorrow to find the poem—

the combustion of tiny fireworks,

the new hole burned through my favorite shirt.

The Deathmobile

I.

Color of a Metallica album,

I can almost see the lack

of shirt sleeves and good sense

due at signing

on an El Camino like this.

How proud he must have been!

How sensual that first touch

of chamois cloth to sheen,

tracing the seam

around the driver’s side door

as if in blessing.

He must have felt

like he had two cocks

when he’d rev it to redline,

dump the clutch, and peel

a strip of hide

off the gravel drive,

the pull of inertia

or some other fundamental Law

he didn’t comprehend

yanking him with a lurch

toward the main road,

and the highway that leads

to all highways.

II.

The car was all she left him in the divorce.

She had always said he spent more time with it,

and now he wouldn’t have her to stand between

him and his one true love. She was cheating on him

but didn’t want to admit it. So he lost himself

in its intricacies, the delicate interdependencies

of a harder heart than his. That summer he dismantled

the entire engine block, cleaned and polished every piece

with a relentless eye—then rebuilt the whole thing, just like new.

This is the part of the poem where I’m supposed to say

his catharsis was complete, that he managed to repair

the broken-down wreck of his life—because hasn’t the car

been a symbol all along for his psyche?

I don’t know. All I know is that, come fall,

that El Camino may have looked a little beat up

on the outside, but under the hood it ran like a Swiss watch.

Like something that hadn’t been pulled apart inside. Like new.

And that he sold it to Brandon for fifty bucks.

III.

And so it is written,

The Deathmobile,

in algae-colored spray paint

against the flat black primer

of the rest of the body,

tattooed across the dented tailgate—

only slightly more garish

in its audacity

than the skull and crossbones on the hood.

IV.

Brandon is a collector

of stray cars, in the same way

some people choose pets

they see themselves in.

After Amber dumped him

to marry her second cousin, he wanted

to celebrate mediocrity.

He wanted to own a stereotype

he could beat the shit out of.

So he gave that car the worst half

of a paint job, got drunk

every day, and took it out

on the roughest roads in the county.

Funny thing, how love can echo

itself. Like hand-me-down clothes

that never quite fit right.

Funny how they tell alcoholics

that the definition of insanity

is repeating the same action,

expecting different results—

but fail to mention that flipping a car

into a river in January isn’t too sane either.

Funny how blurred the trees are,

how riotous the engine pounds

with the hammer down,

as he speeds home to the Farmhouse,

The Black Album

blowing the speakers out,

windows wide open, almost doing ninety. Glenn Hollar is a biographer's nightmare. Not for the reason you're thinking. This much is certain, though: he received his MFA from the University of Maryland in 2011, he currently lives in Tampa, FL, which he's not entirely convinced isn't hell in disguise (what happened to the mountains?), and he has had one of his poems published in Inch. Which is exactly the amount of newspaper column space his obituary will occupy.

Glenn Hollar is a biographer's nightmare. Not for the reason you're thinking. This much is certain, though: he received his MFA from the University of Maryland in 2011, he currently lives in Tampa, FL, which he's not entirely convinced isn't hell in disguise (what happened to the mountains?), and he has had one of his poems published in Inch. Which is exactly the amount of newspaper column space his obituary will occupy.

October 24, 2012

Lost and Found, fiction by Benjamin Soileau

I was drinking beer and washing the dishes that had piled up all week. I figured it would give me something to do to take my mind off of things. There I was, scrubbing and scraping away. I was washing a knife when the blade sliced through the sponge and sank into my finger. It happened just like that and there was a lot of blood. I cursed Mandy then, because it was as if she had slashed me with the knife herself. I wrapped some napkins around it, got another beer out of the fridge and stepped outside the trailer.

Damn, my hand hurt. I strutted around out there in the yard like a rooster, scratching open the earth with the heels of my boots and chugging that beer. I looked down at the napkins and I could see the red spreading through. Just then I heard the door go flying open and slam against the trailer. I looked up and saw that little son of a bitch go flying down the steps and tear across the yard like his ass was on fire. I hollered for him a few times and just figured he’d come back in a bit. What next, I thought.

Back inside I ran my finger under some water and I could see that it needed stitches. I got some Band-aids on it, then wrapped it up tight with some Scotch tape and put on a work glove, although I’m not sure why. I went in the kitchen and grabbed the last beer. I knew I was going to need a lot more before this day was through. I stood there in the kitchen and looked out at the emptiness. She’d taken everything. She even took the rotating fan that I need blowing on me so I can sleep at night. It was just me and Bojangles now and I couldn’t understand why she hadn’t taken him with her. Hell, two weeks ago we were fine. I was going to meetings and coming home to her telling me how proud she was of me. We were back to playing house. But then one night last week after work I ran into this fellow from my group at the Piggly Wiggly and he was buying a case of beer. We saw each other in the aisle and our eyes both said, oh shit. We drank that whole case down at the landing and that was that. Six months for nothing.

I hollered for Bojangles a few more times when I got out to my truck, but he was gone. I was going to have a pity party right then about how everybody wanted to leave me, but I didn’t waste much time on it. I knew I had to go get him. I needed more to drink anyway. I live on a few acres of land at the end of a long gravel drive and I took it slow, leaning out the window, calling his name and whistling for him. I thought maybe he’d gone to find Mandy. I’d tried to find her too, but I hadn’t any luck. I prayed that she hadn’t gone back with her ex-husband toTexas. That’s the only reason I could figure that she didn’t take Bojangles. Ronald the roper wouldn’t care much for a dog with one ear and a heart full of worms. I could picture her asking him if she could take the dog and being told no, and then having this tearful goodbye session with Bojangles in the trailer while her dude rancher waited out in the car. I had to hope that she was around somewhere.

I thought I spotted a dog pissing in the bushes and I slowed down, but then I saw that it was just a deer carcass with a bird dancing around on top of it. I drove on, and I could feel my heartbeat in my finger. I looked out past the oaks that lined the road and out into the fields. I remembered when we got Bojangles from the pound. First thing he did when we got him home was to piss on my work boots. After that he ripped all the tinsel off the Christmas tree and tore into the present I had just wrapped for Mandy. I guess she already knew I’d gotten her some slippers with those fuzzy rabbit heads on them, but she acted surprised anyway. I had a mind to take that mutt on a one-way trip to the woods then, but she loved him. She’d taken him with her the last time she left, but that was only for two nights, and she was only at her cousin’s house, making me sweat. I hoped this time wouldn’t be much longer.

I kept the window down, but sped up a bit. There weren’t a whole hell of a lot of places he could have got off to. I pulled in at Pete’s Palace. Pete had a little sign in the lot with most of the bulbs busted out of it that advertised “the coldest beer in town.” Gayle’s Bait Shop also had a sign that promised the very same thing, and most of the lights on that sign glowed just as bright as they pleased, but they know me down at Gayle’s and Pete doesn’t give me any shit. Plus, he actually keeps his beer in tubs of ice so it really is the coldest, I guess. I walked on in and the bell dinged.

“Hey,” Pete said without looking up. “What you know good?”

“Aww, you know. Same old same old.” I leaned on the counter and watched Pete back there on his stool. He was dabbing paint on a fishing lure with the point of his pocketknife. “Say, Pete. You happen to see my dog running around here this afternoon?”

“I heard a mess of dogs out in the parking lot earlier, but I don’t know if yours was with them or not.” Pete stared down the end of his glasses and kept dabbing at that lure. “What you got one glove on for?”

I told him and then I went back to the tubs to fish out a six-pack of tall boys. I plopped the beer down on the counter, and Pete moved on over to ring me up.

“Hell, he probably just stepped out to get a little tail,” Pete said, stabbing the tabs on that old cash register. “Tell you what. If I see him roaming around here, I’ll keep him here for you.”

I got my beer and headed out. I told Pete over my shoulder that he was a good man no matter what everybody else inLivingstonparish said about him.

The beer was so cold I could hardly taste it. I had the window down and kept calling for him. Mandy’s photo was still taped on my dashboard and I couldn’t help but feel like she was judging me. What did it matter now, I thought. I’d just ride this one out and go to a meeting tomorrow. Start fresh. After a little ways and a few more beers I heard a bunch of hounds crying out. I turned down a gravel drive into a trailer park and parked at the entrance. I put those beers down under the seat and followed the barking down a few sites. I walked up on a little boy with only his underwear on. He was spraying about five beagles with a hose. They were locked up in their pen and they sure didn’t like getting wet. That little kid was just laughing and carrying on.

“Hey, boy,” I said. “Stop spraying those dogs like that.” I peered up in there but I didn’t see Bojangles. That boy just stood there staring at me like I was crazy, letting the hose squirt all onto his bare feet.

“Daddy!” he yelled.

The door to that trailer opened and I’ll be damned if Lonnie LeBlanc didn’t come marching down the steps. We used to work together in high school, shucking oysters at Hardison Seafood.

“Quit your hollering, boy,” he said when he got down next to the kid.

Lonnie didn’t have his shirt on either and I thought he was going to smack that boy, but then he noticed me standing there. “Hey, Henry, where y’at?” He came walking over to me and I shook his hand.

“Damn, Lonnie, what’s it been, six months?” I knew it had been six months because that’s when Drew Farraday busted Lonnie’s head with a shovel down at Harry’s Bar. They carried him out that parking lot on a stretcher and nobody had seen him since.

“Yeah, you right,” he said. “I just been staying at home mostly. I still can’t work.”

I didn’t really want to get into it. “Say, Lonnie, you hadn’t seen my dog running around here?”

“I don’t know your dog,” he said, finishing up his beer and tossing it in the grass.

“He’s about yay high,” I said, and put my hand three feet off the ground. “He’s black, only got one ear.”

“Hell, I ain’t seen nothing like that.”

“Well, thanks anyway.” I turned to walk away and he grabbed me by my elbow.

“Come on in, Henry,” he said, leading me toward his old trailer. “Tina’s up inside making daiquiris. Come get you one.”

I turned him down once and then I let myself get pulled inside. As soon as we got up the cinder block steps and to the door, that boy turned the hose back on those dogs and they all started up again.

That old trailer smelled like rum. Tina was in the little kitchen with the blender going. She was wearing an old Bon Jovi tee-shirt with pink pajama pants. I’d only ever seen her wearing her Piggly Wiggly outfit. She turned around when we came in and acted like I wasn’t even there.

“Baby, make one for Henry, too.” Lonnie plopped down on the couch and moved a pile of clothes for me to sit down. They had curtains over the windows and it looked like some hippy hideout. There was a shelf on the wall over the TV with about six fiber optic flowers in glass cases, all plugged in and glowing. The sound of those hounds outside was getting to me.

Tina walked over and handed us each a coffee mug full of peach daiquiri. “You think you’re Michael Jackson or something?” she said, nodding at my glove. That’s the most I ever heard her say. She went back to the kitchen, poured herself one and sat at the little kitchen nook.

“So, Henry,” Lonnie took a big sip on his drink. “What you been up to lately?” He looked over at Tina and they smiled at each other and I figured they knew about me and Mandy.

I started to tell them that I hadn’t been up to a damn thing, but then Lonnie set his drink down between his feet and grabbed the sides of his head. “Awwww. Shit! Owwww!”

Tina started laughing and Lonnie just rocked from side to side, cradling his big head. He stopped after a minute and picked his drink back up. “Fuckin’ brain freeze,” he said and started laughing.

“I’m just looking for my dog,” I said and looked over at Tina. “You seen any stray dogs roaming around here?”

She just looked at me and shook her head and I heard a toilet flush in the hallway. The door opened and this big fellow came waddling into the room. He walked right past me and sat down in a rocking chair at the end of the couch. The smell trailed right after him.

“Goddamn, Ricky.” Lonnie started swatting at the air in front of his face. “Can’t you shut the fucking door if you gonna do that?”

Ricky just looked over at me with a big grin on his face and didn’t say anything. He was wearing a yellow tank top with the words, “Slick Rick” written on it in magic marker. Tina got up and went to the bathroom door to shut it. She came back into the room with some Lysol and started spraying it onto Ricky. Lonnie was laughing and so was Tina, and that man just sat there with a grin on his face and let himself be sprayed. I could taste disinfectant in the back of my throat.

“This is my brother, Ricky,” said Lonnie. “Ricky, Henry.”

I nodded at him, but he just sat there, grinning. Tina brought him a mug. That drink was strong, nothing but pure rum, I guessed, and a little bit of canned peach.

Ricky reached down by the side of the couch and grabbed a big purple bong. He lit up and started sucking on it. Tina walked back into the room and poured the rest of the daiquiri from the blender into Lonnie’s mug. She set the blender down on the coffee table and sat down on the other side of Lonnie. Ricky started coughing like he was going to die, and then he nudged me on the arm and passed that thing to me. I handed it over to Lonnie, but he pushed it back over.

“C’mon, Henry. Get you some.”

I took a little puff and it burned me down deep inside. When I blew out the smoke I saw that it was a little more than I bargained for. I started coughing and then I handed it on down. The dogs were howling still.

“Baby, tell T to knock that shit off,” Lonnie said, his voice strained through a lungful of smoke.

Tina was twirling her hair. “I will not,” she said. “You know he loves playing with those dogs.”

Lonnie exhaled a huge cloud of blue smoke that spread to every corner of the room. “I guess at least I know where he is.”

After a little while I found myself staring at one of those flowers on the mantel. I thought about my old trailer without Mandy in it. Even after a whole week I thought I could still smell her perfume in there. I felt bad for Bojangles. Did she leave him behind because he reminded her of me? The pot was making my head swim and I could hear everybody around me laughing. I remember what Mandy told me about attracting lower company.

I looked over and Tina was counting down from ten, looking back and forth between Lonnie and her watch. Lonnie and his brother were both leaning forward, clutching their coffee mugs and watching Tina with big, dumb grins on their faces. I gathered that they were going to see who could down a whole mug full of daiquiri first. She finished counting and when Lonnie swung his mug up to his face I heard a dull “clunk” sound.

Lonnie screamed, “Oww, fuck!” He had his hand on his mouth and I could see blood on his fingers. The edge of his coffee mug was chipped off and he let it fall to the carpet. Ricky started laughing and then Lonnie joined in. He lifted up his lip and pushed out his front tooth with his tongue. It lifted up just like a trap door opening. He grabbed onto the loose tooth and then plucked it out. “Goddamn, you see that?” he said, laughing. “That shit hurts.”

Tina ran over to the kitchen and grabbed a roll of paper towels. I stood up and moved over to the door. I needed to go get my dog.

“C’mon,” said Lonnie through bloody teeth. “Don’t go yet.”

“I got to go get my dog, Lonnie.” I watched Lonnie hand his tooth to his brother, who started examining it with his lighter. “Y’all take it easy.”

When I got outside, I shut off the hose and that boy stood there and watched me walk back to my truck.

I was feeling a little paranoid driving away from there. I got off the highway and did my daily drive-by down Carter’s Lane. Mandy’s cousins lived down that road, and if she was still around, then that’s where she’d be. I saw a couple of her cousin’s kids standing in a little plastic blue pool, naked as jay birds, splashing water on each other, but no sign of Mandy. I stepped on the gas so nobody would see me, and circled around to get back on the main road. I pulled out the beer and set it on the passenger seat. It was starting to go down good again, and I figured I should drop by Uncle Lee’s house. He’s good company, and lives in a house that he built right onLakeMaurepas. During better times, me and Mandy would take Bojangles out there for the day.

Uncle Lee was sitting on his swing just like I figured he would be. It sat at the end of his huge back yard facing the lake. He was holding a slingshot and watching some ducks messing around in the water. He looked up and called me over. I sat down next to him and asked him how he was doing.

“Smells like you done missed the wagon,” he said. “Might as well,” he nodded his big head toward the ground. There was a big tin tub at his feet full of iced-down wine coolers. I grabbed a blue one.

“What the hell you doing with a slingshot, Uncle Lee?”

“What the hell you doing with one glove on?”

I asked him about the slingshot again.

“I’m protecting the chastity of these lovely bitch ducks,” he said, drawing on his wine cooler. His hair was long and silver, stained a little yellow from fifty years of smoking. He was wearing the same blue overalls that he always wore. I think he put them on the day he retired from the plant, and never took them off again.

I drank my drink and watched the ducks.

“You know anything about duck sex?” he said.

I told him that I was out of the loop.

“Well, ducks don’t tend to make love,” he said, pulling his pack of Lark’s from his pocket and shaking a couple out. He lit them both in his cupped hand and gave me one. “The bull duck doesn’t believe in it. No Sir. He’ll just sweep on in from the pretty blue sky and fuck her silly. He’ll push her down and just go at it, and then up and fly away. Attack and release. You ever seen it?”

“No Sir.”

“But the bitch duck is smart, see. She’s got a series of canals inside of her poontang, and she can open and close them like valves. So if some goofy ass retard duck rapes her, she can pinch off those valves so his jism doesn’t get to where it needs to go. And if she wants to have some ducklings with a particular stud, well, then she’ll pinch them valves the right way so that his mess gets to her honey pot.”

“So how do you know which ducks are the ones that she wants to have babies with or not?”

“I don’t,” he said, scratching his head. “But they’re all rapists.”

I didn’t ask Uncle Lee how he knew so much about duck sex. I asked him if he’d seen Bojangles and reached down and grabbed another blue drink.

“He ain’t come around here yet. Don’t tell me you missing that dog.”

I told him briefly what was what and I was aware that I had to work for some of my words.

Uncle Lee stabbed me with his icy green eyes for a second and then trained them back on the water. “Boy, why don’t you kick them boots off and stay here for the night. Your old dog ain’t worth a shit.”

“It ain’t my dog,” I told him.

“I went up to Gayle’s the other day to get some crickets and I saw some cowboy buying her some scratch-offs.”

I didn’t know what to say to that. Three ducks came swooping down and went skipping across the water until they glided to a stop near the others.

Uncle Lee reached into his pocket and came out with a little round lead ball and slowly fitted it into the pouch of the slingshot, carefully slipping his arm through the brace to grip the handle. “You got to get your head on right, Henry,” he said, pinching the ball in place and pulling those rubber straps back just a bit.

The sun was getting lower on the water, and it wouldn’t be long before it started going pink. I watched some moss dance in the breeze over the water and slugged the rest of my drink.

“Look it,” said Uncle Lee.

One of the new ducks was ruffling his feathers and circling around a female, croaking and carrying on.

I stood up.

“You stay here tonight,” he said. “You can drink all you want.”

“I’m just going to the bathroom,” I said, and started walking toward his big house.

“You gonna want to see this,” he called after me, but I walked into his front door and slipped out the back.

I pulled into the Piggly Wiggly and parked facingMain Streetso I could see down the road in either direction. I saw Sheriff Thibodeaux resting on his cruiser and flirting with the cheerleaders at Frost Top, but I was seeing two of him. I needed to sit still for a bit. I put the radio on and Buck Owens was singing about having a tiger by the tail. I thought that I didn’t have shit by the tail. I hoped Bojangles was okay. I hoped he hadn’t gotten in another fight and had his other ear ripped off. I opened another beer and watched the folks streaming out of the store in my side mirror. After a while I saw Mandy’s cousin come out. I leaned back low so she wouldn’t see me and watched her. She was in a hell of a hurry and her arms were full of groceries. When she got close to my truck I saw her look up and we made eye contact in the mirror. I got out then because I saw her turning around.

“Hey, Claudia,” I said, jogging up to her. “Let me give you a hand.”

“I don’t need no help,” she said, tucking the bags up against her like it was a baby she was trying to protect.

I moved in again to help her out, but she turned away and when she did, a big case of diapers fell on the concrete.

“Dammit, Henry! Look what you done made me do.”

She leaned down to scoop up the diapers, setting down her grocery bag to do so. I could see a box of Q-tips and some Little Debbie’s sticking out of the bag. I just stood there looking down at her and then I noticed that I still had a beer in my hand.

“Where’s Mandy?” I said.

“Why should I tell you?” She got the diapers positioned on top of the grocery bag and then she stood up.

“Because,” I said. “I need to know.”

Claudia stood there looking at me like I was something foul behind the bars at the zoo. I saw her look at the beer in my hand.

“Where is she?”

“She ain’t available so you might as well just go to Harry’s and find you a girl that deserves you.”

“She left some of her momma’s stuff behind, some rings and pictures.” I saw her look at me and I knew she didn’t believe me. I could tell that she knew much more than I ever would. “Just tell me so I can mail it all to her.”

“Goodbye, Henry.” She walked on past me to her old broken down piece of shit.

“At least tell me who she went off with,” I hollered after her. “Was it that shit kicker?”

I watched her put the bags in the back seat and then stop and look at me before she got in. “If you come by my house ever again, I’ll have you arrested.”

I watched her get in and drive off and I threw my beer at the car. It banked off the fender, but I figured I was the only one who even saw or heard it.

I got back in the truck then and looked around on the seat for another beer, but I couldn’t find any. I popped the seat up and just about crawled up under there, but there was nothing left. I got back behind the wheel and slapped myself in the face. I was going to need some more beer. I started to get out of the truck, but Sheriff Thibodeaux’s cruiser pulled into the lot and parked right in front of me. I looked ahead and saw him looking back at me through his windshield, and I thought, here we go again. He got out and came on over.

“You all right, Henry?” he said, leaning into my window.

“I’ve been better, Charlie.”

“You think you ought to be drivin’ around town right now, Henry?”

“I’m looking for my dog. You seen him, Charlie?”

“No,” he said, leaning down to get a better view of the inside of my cab. “I ain’t seen your dog.”

I knew that I wasn’t giving him a whole lot of options and so I just let him have it. I told him about Mandy being gone and that I needed to find our dog. He asked me why I was only wearing one glove and I told him that, too. He nodded along while I began to convince myself that I would find Bojangles and the three of us would have a tearful reunion when she came rolling up tomorrow. He just looked in on me and I could tell by his eyes that he knew something, too. Jesus, I thought. Everybody knows the score but me. “I got to find that dog,” I said.

“Look, Henry,” he said, standing back up and looking around the lot. “I tell you what I’ll do. I’ll go get you some coffee from inside, and I want you to sit here and wait this one out, okay?” He leaned back on the door of the truck and waited for me.

“Yeah. Okay, Charlie. Thanks.”

As soon as he got in the store, I cranked my truck up and kicked it in reverse, slamming hard into a parked Suburban. I turned around and saw that the truck I had hit had a horse trailer hooked up to it and people in the parking lot were looking at me. I didn’t wait around. I hauled ass forward and clipped the front of the Sheriff’s cruiser. When that happened, one last golden can shot out from under the seat and I reached down and clutched that thing like a trophy.

I coasted down that long gravel drive and flipped my brights on. As I turned into my dirt turnoff, the headlights swept across the yard and caught old Bojangles sitting on the concrete steps leading up to my front door. His eyes were twinkling back at me like two blurry blue stars. I cut the engine and sat there, watching him in the headlights. I wondered where he’d been. I figured he was hungry and I tried to remember if I had anything in the fridge. She’d really left him high and dry. Looking at him looking back at me, I could see he really needed me. I was all he had in this world. I couldn’t stand to look at his disfigured, stretched-out shadow on my front door and so I shut off the headlights. I pulled her picture off the dash and threw it down to the floorboard. That’s when I heard a car turn off the highway and start creeping up toward my place. I got out of the truck then, and went and sat down next to Bojangles on the steps. I pulled him to me and held him against my chest, and we sat there together, listening to the sound of crickets, and those tires coming.

October 21, 2012

Small Things, fiction by Eric Boyd

Eric Boyd was born in North Carolina, attended some school at the Maharishi University of Management in Iowa, and currently lives in Pittsburgh, Pa.

A winner of the Pen American Center's 2012 Prison Writing Contest, Boyd has had work awarded and featured in several journals including Fourth River, Nanoism, Hillbilly Magazine, and the Rusty Nail.

Boyd's first collection of short stories, Whiskey Sour, was released last spring by Chatham University / Nervous Puppy Publishing. The collection will soon enter its second printing.

October 18, 2012

A Brutal Act of Ketchup, fiction by Gary Clifton

Hadn't oughta been no damned trouble at all, 'cuz wasn't me did anything wrong — well not exactly. I'm a falsely accused man. Then I got this call today. The FBI was lookin' for me…some crap about interstate travel to commit murder. Hell, I ain't kilt nobody hardly ever.

"Sonny Wilson Claypool," old sheriff Kebow back home in McCurtain County, Oklahoma, said several times. "You're big as Poland, mean enough to eat a live chicken, and useless as tits on a tomcat." Big and hungry maybe, but eatin' a whole live chicken? That's a stretch.

Life slid to hell on three wheels after I'd started four games at left tackle as a freshman at Oklahoma Southern, livin' with Eula Mae Frakes, the O.S. provided live in. Was her figured something' didn't lay right — me. Word got around I was gay — hellfire, I didn't know. I lit a shuck for the bright lights of Dallas to join thousands of others of similar persuasion. Found work as a beer joint bouncer with a new universe of good friends.

This dropout, dirt bag who'd been an O.S. running back, Napoleon Jones, drifted into the joint one night. I sold him a $300 baggie of grass. But when Napoleon strolled to the parking lot with the stash to get some cash, he forgot to come back. In an hour, I found the little weasel at a topless joint on Harry Hines, smokin' my shit and ooglin' skinny women. I abducted him at gun point, duct-tape him up pretty good, and started for Lake Lewisville to toss his ass in.