Rusty Barnes's Blog: Fried Chicken and Coffee, page 19

April 1, 2015

And Rapture, fiction by Sheldon Lee Compton

There was this time I thought Gabriel was blowing his horn and dive-bombing me into Hell. Turned out it was a Mack coal truck across the road at Dale Trivette’s Trucking pulling onto Route 610.

I was in bed and thinking about what Mother told me while we had a snack that evening.

“Don’t worry if you’re a sinner and the time comes and Jesus returns,” she said. “The Bible says Gabriel will sound his horn to signal the Lord coming.” She leaned down to me and put her soapsuddy hand against my face. “When you hear that horn sounding out, just ask the Lord to forgive your sins and you can go to paradise.”

She smiled so big when she went back to eating her strawberry Jell-O.

So when that Mack honked to pull onto Route 610, I started praying. It wasn’t much of a prayer, you know. Not the really practiced kinds of prayers you hear in church. What I was saying was mostly out of fear and it all ran together and maybe I was whimpering a little, too.

A few days after I started vacation bible school I was at mom’s house for the weekend. My real mom, not my grandmother who I called Mother. I told her I was going to get saved. She had just had my baby sister, whose dad was mean but gone most of the time. She looked tired and hurt before I said anything. When I told her, she stared for a long time at the floor and then went into the bathroom.

I bent down and talked under the door.

I said, “I know I’m just a little boy, but I want to walk with Jesus Christ.” I pushed my mouth close to the opening between the bottom of the door and the floor. “You can, too, Mom. If you hear Gabriel blowing his horn, all you have to do is ask Jesus to forgive you and you can go to paradise, too.”

Vacation bible school ended not too long after that and I started thinking more about playing baseball than I did about Jesus and sin and Gabriel. But when winter came back around, I stood in Mother’s kitchen and started imagining again what Gabriel would sound like blowing his horn.

Outside the kitchen window, the grass in the front yard, the porch rails, the hummingbird feeders, were covered in ice. Even whispers seemed to bounce off the frozen things and go on forever. They bounced and bounced and made such a loud sound when they did.

Sheldon Lee Compton is the author of the collection The Same Terrible Storm, which was nominated for the Chaffin Award in 2013, and the upcoming collection Where Alligators Sleep. His writing has been widely published and anthologized, most recently in Degrees of Elevation: Short Stories of Contemporary Appalachia. He was a judge's selection winner in 2012 for the Still: Journal Fiction Award and a finalist in 2013 for the Gertrude Stein Award. He survives in Eastern Kentucky. Visit him at bentcountry.blogspot.com.

March 29, 2015

Parade, fiction by Henry Hope

“I can’t abide this shit. I can’t and I won’t.” Desmond, my mother’s new boyfriend, jabs his oily knob of a finger into my forehead. His breath is coming in rapid little spurts, a sign, I have learned, that his anger is one notch away from becoming physical. “I don’t think you want me to hurt you but if that’s what it takes then that’s how it’ll be. Now put ever one of them tools back where they go and get your sorry ass out of here.” Desmond slams his hand on the workbench. The several pairs of pliers and screwdrivers I’d laid out jump off the particle-board counter.

When I don’t move, Desmond steps in close. I can smell the scorched wheel-bearing grease spattering his hands and forearms, feel the burn radiating from his shaved head.

“Looky here, boy” he says. “When I tell you to do something I mean it. Now get busy.”

I angle around him and reach for the nearest pair of pliers. He waits until I slip the silver handles into their pegboard rings.

“Soon as you’re done,” he says, “I need your help. So hurry it up.” With that he is gone.

I think of my mother while pegging the tools. Think how she is a lousy judge of men, always has been. My own father, before he died, was a drunk and a crook, always plotting how to get something for nothing. Cheat, steal, con, it made no difference to him. He got shot dead nine years ago in the parking lot of the Rocket Launch B&G. I was six years old. But as young as I was I had seen enough, had lived through enough of what he called discipline to keep my distance from him. I was glad he was gone, felt like whoever done the shooting done us a big favor.

I enjoyed the freedom while it lasted. Then the parade started. Most of the men my mother brought home disappeared after a night or two. Some made it a couple weeks. The only halfway good one she hooked up with was here four months before she got bored and ran him off. And now it’s back to the likes of Desmond.

“If you were flesh and blood I’d shoot your ass,” I hear him yell. “Turn you into a human colander.”

I’m sure he’d like to shoot me, too. He’s said so. But right now I know his threats are directed at his truck. It broke down yesterday. The left front wheel locked up when he pulled out of the yard for a trip to Billy Morrison’s place the other side of Pomaria. He never made it to Billy’s. Didn’t even make the hundred or so yards to County Road 2 that runs past our singlewide.

I know he buys drugs from Billy because he once told my mother, “Billy got a new shipment of roxies in this morning. I’ll stop by on my way home tonight and see what I can get from him.”

If pain pills and whiskey were a planet, you could look through a telescope and see seventy, eighty percent of the people who inhabit this holler orbiting in its gravity. It has been this way as long as I remember.

I slide the last screwdriver through its double-ring holder just as Desmond yells, “What the hell, Donnie! Ain’t you done with them tools yet?”

When I step from the tool shed into the yard I see the coal-black soles of his Dr. Martens first, and then the rest of him sucked beneath the front axle of his Chevy. The tips of his boots are tapping empty air like he’s keeping time with some drug-addled country song playing in his head. The wheel is off, a dark circle of rubber and metal prostrate on the cracked earth of our yard.

For a single blinding moment I want Desmond to feel the pain I feel when I have to pretend I’m asleep while he slaps my mother around in the next room. I want to ram a screwdriver through his fat, hairy chest, spit in his face, promise him he will die a slow death by my hand. It is then I see the jack handle jammed into the housing. I notice there is no jack stand to take the Chevy’s weight should the jack fail. With one solid kick I could send Desmond on his way for good. Watch him squirm, stomp his helpless legs while the Chevy squeezes the final gasping breath from his collapsed chest.

But then what? Déjà vu is what. The parade will commence all over again. So as much as I hate the man I’ll take my chances with him, and then the one after him, and the one after him. I can’t say when the parade will end or even if it will end. But what I can say is it makes me sick to be here and be a part of it. But that is the card I drew and until a better one comes along I’m stuck, just like Desmond if I trip his jack.

Desmond cocks a leg in my direction. His greasy arm flops from the wheel well. “Hand me that socket set.” he says. “And make it quick. I don’t care to lay in this dirt no more than I have to.”

I walk to where the socket tray is spread open and slide it toward him with my bare foot, careful not to rush.

“Dammit! Hurry it up!” he says, more of a grunt than actual words. “If I have to crawl out there and get it myself you can bet I’ll wrap you around that tire while I’m at it.” When the tray is close he snatches it, pulls it within easy reach.

While Desmond works I squat next to the truck, hoping the socket will slip, throwing his hand into the tie rod and ripping the skin from his knuckles. No such luck. Across the yard, through the singlewide’s tiny bathroom window, I see my mother hunched over the sink. She is holding a washrag to her bruised cheek. I wonder how many bruises, how many black eyes, how many broken bones she has had in her life. I wonder how many she will have yet. I hope for her sake it won’t be more than she can count on one hand. And as I wait for Desmond to call it a day, I hope for my sake I won’t have to be here much longer to serve witness to it.

March 26, 2015

Harry Crews' Unfinished Novel, poem by Dale Wisely

Harry realized then that the book was so intimate

that all he could do was mark his place

with a thumb, close the manuscript,

look out the window, and try not to cry

because, he said, it’s so damn close to the final shit

and because the book asked the reader a question

that only God Almighty should be able to ask

because, see, Harry said, it’s just

such a freaking, horrifying burden

to have that question asked of any man.

And then Harry refused to describe either the novel

or the question and when, under influence of drink,

you protested and pressed the point he threatened

to kill your ass, man, to spare you the pain

of ever knowing that awful load

that Harry now bears for you and for us all.

Dale Wisely founded and co–edits Right Hand Pointing, One Sentence Poems, and White Knuckle Chapbooks. He can draw a Venn diagram to help you understand the relationship between muscadines and scuppernongs.

March 23, 2015

Feather, fiction by Elizabeth Glass

Wayne leaned back on the rock where he was kneeling next to Mandy when she told him she was pregnant. He could feel the cool moss seeping dampness into his jeans. He saw Mandy looking and acting older after having a baby. His nose crinkled at the thought. He never minded that with other girls, most of the girls he had dated had kids, but Mandy was different—young as he was and pure as the first winter snow.

“Aren’t you going to say anything?” Mandy’s blue eyes were wide, and she used the baby voice that before he found cute.

“Oh. Congrats, I guess.” He sat back further and took a swig from his beer, then pulled his fingers through his beard. He told people he had a beard to get girls, but the truth was it so he could buy beer.

“What’d L.J. say? Guess he’s happy,” Wayne said.

“Oh, I ain’t told him yet.” She rubbed her hand across her belly.

Wayne stared at her. “Why didn’t you tell him?” He looked back into the woods, shifting position on the rock off of an area that was poking his hip.

“You know he and I ain’t been hitting it. You’re the only one, Wayne.” She bit her lips. “I haven’t told him cause you’re its daddy.” Mandy looked at Wayne, then down at the ground. She picked up a beer, popped it open and took a long swig. “Guess I have to quit drinking.”

He swung his boots around the rock and looked into the ravine. They spent most of their time together there. Sometimes they’d risk it and go to Mandy’s, but they never knew when L.J. might stop by. Sometimes he came by the house for lunch or made an early day of it. Once they nearly gotten caught, but Wayne jumped into the shower, and Mandy told L.J. Wayne’s water was turned off so he was borrowing theirs.

Wayne lived in his mother’s basement and he could do almost anything he wanted there, with one exception: he couldn’t bring married women around. Every girl he took over there, his mother would poke her head down the steps and yell, “Come here, you married?” She would have to look his mother right in the eyes and say “No ma’am.” Then his mother would pick up the girl’s left hand and look for a ring or marks where one had been. It’d gotten to be such a pain that unless a girl actually was single, Wayne didn’t take her there. And since nearly every girl he had been out with was married in one form or another, he learned to be creative.

He looked into the ravine, thought about jumping off the edge of the cliff, but figured with his luck he’d just wind up paralyzed. “A kid, huh?” His back was toward her.

“Yeah. A kid.”

“Well,” he cupped his lighter to the wind to light a cigarette, “I guess we can get married and all. I could probably get on full time at the track.”

“Oh, well, there’s something else I have to tell you, too, Wayne.” She paused. “Could I have a drag?” She pointed to his cigarette.

“The pack’s there, get one.”

“No. I gotta quit. Just one drag.” He handed her the cigarette, watched her wine-colored lips curl around the end. God, she’s sexy, he thought, eyeing her mouth as she exhaled smoke. When she gave him the cigarette back, her lips had made a dark burgundy kiss on the end. “Like I was saying, there’s something else. L.J. got transferred.”

Wayne paused, looking out over the rocky hills. “Hmmm. Well, at least we won’t have to see him around everywhere.”

“Wayne, I’m going with him.”

Every day, Wayne replayed in his mind the day Mandy told him she was pregnant with Feather. Sometimes he made changes, things he wished he said like, “If it’s my baby, you’re staying here. The hell you’re leaving!” He didn’t realize how much he wished Mandy was with him in Kentucky until he got the first letter from Alabama with baby pictures of Feather tucked inside, a coral-colored kiss on the envelope’s seal. Mandy’s changing and I’m not even there to see it, he thought, looking at the lipstick color on the envelope.

He put one of the pictures of Feather on his bathroom mirror and one in his wallet so he’d see her every day. So that he’d know just why he was working fifty hours a week cutting meat at the track—the steaks and chicken for the people upstairs, where he could never afford to go. Why he put up with his boss yelling at him that he wasn’t cutting the meat perfectly, with bones slicing into his hands even though he wore thick, hot, black gloves made to keep just that from happening. Every week he sent a third of his check to Mandy and Feather at the post office box L.J. didn’t know about. He knew it wasn’t anything compared to what L.J. gave her, but at least he was giving them something. At least maybe Mandy could get Feather a toy or herself a new pair of jeans. The rest he split into three parts. One part he put in an old mayonnaise jar next to his bed to save for bus fare and hotel money for Alabama. Every time he got enough saved, he figured he’d go spend a week or so with them. At least be in the same town as them. One part he gave to his mama to help out with paying for the house and bills, the other part he used for beer, cigarettes, and food.

Wayne stared at himself in the mirror. God, I look thirty fucking years old, he thought, splashing water on his face. He looked around. He hated bus stations more than anything he could think of: they all looked just alike, they all stunk, and there wasn’t a damn place to sleep and be comfortable. He walked out of the restroom and found some old guy sleeping on his worn sleeping bag. He’d had it since the year he was in the Boy Scouts, before he got kicked out for smoking on a camping trip. It was way too short for him; if he put his whole body in it, his shoulders and head stuck out at least a foot. Usually he let his feet stick out the bottom instead. He watched the old man snore; he looked like he hadn’t slept in weeks. Shit, I can’t just wake him up, Wayne thought, so he headed toward the bus station restaurant and ordered some overpriced coffee while he waited. By the time the coffee got there, the old man and Wayne’s sleeping bag were gone.

When he got to Alabama, Wayne looked around but didn’t see Mandy. He went to the ticket counter, “You seen a cute girl, blonde hair, carrying a baby?”

“No. You Wayne Frederick?” the man asked.

“Yeah.”

“Some woman called, said she can’t pick you up, but for you to go to the Motel 6 and she’ll call you.”

“When?”

“Shit, what do I look like? An answering machine?” The man shook his head.

Wayne walked off toward the street. He looked up the address of the Motel 6, then found it on his map. He couldn’t walk that far so he hoped he could hitch a ride with someone. Once he got outside, he found the police station was on the same block as the bus terminal, so he went back in to call a cab. It cost fourteen dollars to take a cab to the motel—fourteen dollars he hadn’t counted on spending.

It was the next day before he heard from Mandy. She pounded on his door at eleven in the morning. “Ugh, what? Go away. No maid service.” He worked third shift. The trip had messed with his schedule.

“It ain’t the maid, Wayne. It’s me.”

He crawled out of bed. His hair stuck up like he had teased it with a comb and sprayed it stiff with hair spray. As soon as he opened the door, he went back to bed.

“You look like crap,” Mandy said, looking at him.

“One of us has to. I only look as bad as you look good.” He looked at her hair swept into a ponytail, her coral lips thick and pouty. “Where’s the baby?”

“She’s with L.J. right now. He wanted to take her to this baby-bed place that he sells to. They want a baby for a commercial, so he’s showing her to them.” She sat on the edge of the bed. “If you go get cleaned up, I’ll remind you why you missed me.”

That whole trip, it was like Wayne and Mandy hadn’t been apart. She brought Feather over every morning around ten with a tiny baby bed, and food and beer for them. They lay around watching The People’s Court making bets on who would win.

A couple years later, Wayne realized nearly two days had gone by that he didn’t think about Feather. His daughter. He was pissed that he forgot about her that long. He took his mayonnaise jar to Charlie’s Tattoos While You Wait. He walked in, looked around and said to the tattoo artist, who turned out to be Charlie himself, “I have a beautiful daughter, wanna see a picture?”

Charlie nodded and Wayne handed him the photo, curved and warm from his wallet.

“She’s cute,” Charlie told him. “How old is she? ‘Bout a year?”

Wayne flushed, “No, she’s two. This is an old picture.” He turned the picture over and saw the date printed in blue ink in Mandy’s bubble handwriting on the back, December 28, Feather’s first birthday. “Damn,” he mumbled, “the newest picture I have is over a year old.”

“Yeah, I got a couple of those around, too,” Charlie laughed. “You wanting a tattoo? You can look around. There’s lots of examples. Plus we got pictures of some of the custom ones we done.”

“I want a feather, with FEATHER written under it.”

“You like feathers, huh?” Charlie asked.

“It’s a name.”

“Aaah, a girl. Bet ya twenty bucks you’ll be back within two years to get it tattooed over.”

“No, it’s the baby’s name.”

“Aaah.” Charlie got his tattoo gun ready.

Over the next few years, Wayne kept up his trips to Alabama, and was still cutting meat at the track. He’d become a vegetarian because the sight of meat made him nauseous. The older Feather got, the less he was able to see her when he went to Alabama. “She’ll remember you. She’ll tell L.J.,” Mandy said after Feather learned to talk. If he couldn’t see Feather, it made it hard to see Mandy. And if he couldn’t see either one of them, it seemed pointless to go, but he did.

On Feather’s fourth birthday, Wayne sat in his bedroom after work thinking. It had been over six months since he’d seen her. Mandy hadn’t spent a lot of time with him last time. Shit, he thought, it’s my kid’s birthday. He took shots of Jim Beam, one for every year of Feather’s life, then started taking one for each year old Mandy was. He poured his mayonnaise jar of money out onto his bed and counted. Ninety-two dollars and eighty-seven cents. Not enough for bus fare and a hotel. “Damn.” He walked into the bathroom to wash away the stale smell of meat and sweat. He’d helped a buddy muck at the track muck a stall, so also smelled of hay and manure. When he saw the picture of Feather he’d put on his mirror years ago, he stopped. “Aw hell, I’ll fuckin’ hitch.”

He grabbed a blanket and stuffed some clothes into a duffel bag, collected the money on his bed, and stopped on the way out the door only to grab an apple out of the fridge and write his mom a note.

He didn’t have a lot of luck hitchhiking, and since he didn’t shower before he left, when he did get picked up, people made him get out about a mile down the road. Just past Nashville, a guy in a truck picked him up.

They rode in silence a few minutes, then the driver looked over at him. “Hey man, you fucking stink!”

“Yeah, I got off work and I’m going to see my kid,” Wayne said. He expected to be dropped off, but was hoping to draw it out as long as he could. It was colder than the ice box at the track outside, and damned depressing sitting on the side of the road waiting.

“Look buddy, I can’t take that smell. You’re welcome to hop in the back if it isn’t too cold, but I can’t stand you up here.”

Wayne got out, glad to at least he’d still be moving. He huddled close to the cab of the truck, pulled his blanket around him, and fell asleep.

When he got to Alabama, the guy dropped him at the exit a couple blocks from the Motel 6. As he checked in, the woman eyed him like she’d just seen him on America’s Most Wanted.

He shut the door to his room and was going to go back to sleep. “I smell like I fucking killed somebody.” He took his clothes off and threw them in the sink. He started the shower, but then called Mandy.

“Hi!” she said when she answered the phone.

“How’d you know it’d be me?” he asked.

“Hell. Wayne, that you? Shit, what are you doing?”

“Came to see my daughter. Brought her some stuff for her birthday.” He looked down at the Kentucky Wildcats baseball cap and pen with a velvet rose cap that opened like a jewelry box with a little “pearl” necklace inside. He’d picked them up at a Super America on the road. “Well, it’s not much,” he said.

“That’s real sweet of you,” Mandy said. “Wayne, I have a new friend here. He’s coming to get me and Feather and take us to Wal-Mart. We could stop by.”

He knew it would happen sooner or later, another guy would come along. He even wondered if there’d been one the last time he was here because Mandy wouldn’t even kiss him. She said it was her time of the month, but that wouldn’t have stopped them kissing. “That’s fine.” He hoped he’d get to see her more than just for stopping by. “I gotta shower. I stink like something dead’s been out in the sun too long.”

“Half hour?”

“Yeah.” He hung up the phone, then called work. “I’m sick as a mangy street dog. I’m gonna be laid up a while.” When he got off the phone, he opened a beer and took a gulp, then took a shower.

Wayne didn’t get to see Mandy or Feather without Mandy’s new boyfriend, Rick, being around, but he and Rick got to be pretty good buddies. Every night when Rick got off work delivering chicken, he’d get a bottle of whiskey or a case of beer and go over to the Motel 6 and he and Wayne would stay up drinking till morning.

Since neither of them could be with Mandy at night, they figured they might as well keep each other company. New Year’s morning, they sat outside the hotel room with bedspreads wrapped around them, smoking cigarettes. They watched the sun come up over the gas station.

“Hey man, you love her?” Wayne asked.

“Aw, hell, I don’t know. Yeah, I guess,” Rick said. “I don’t know. Look, I got to be going.” He got up and headed toward his ‘70 Challenger.

“You got the coolest fucking car, man, the coolest,” Wayne said, then lie back on the sidewalk and fell asleep.

That morning Mandy showed up and woke Wayne up from outside his room. “Don’t tell me you done spent the night out here.” She helped him up and over to the bed. “Look Wayne, we have to talk. There’s something I gotta to tell you.”

Wayne got off the bed and walked over to the sink. He grimaced when he saw his reflection. He looked like hell. He turned on the tap and filled a plastic cup with water, swished some in his mouth and spit, then poured the rest of the water over his head. “Shoot.”

“Okay. Well, it ain’t good news.”

“You’re pregnant and the baby’s mine.” He tilted his head back and laughed. When Mandy didn’t make any noise, he looked at her. “Sorry. It’s a joke. I’m glad we have Feather.” He wanted to touch her, put his hand on her shoulder, but she sat abruptly in one of the vinyl chairs near the window.

“Well it’s about her. You know how I said L.J. and me wasn’t making love back in the days when you and me was?” She got up, paced for a minute, then sat on the edge of the dresser.

“But you were.” He took his shirt off to get ready for a shower. He knew what was coming next and he’d be damned if he would spend New Year’s Day in Alabama.

“Yeah,” she said. “Look, I didn’t lie about Feather. I think she’s yours. It’s just that, well, I’m not for sure.”

Wayne walked into the bathroom, got in the shower, and felt the hot water sting his skin that was still rosy cold from sleeping outside.

Mandy followed him. “Wayne, I loved you. I didn’t want to go off to some other state and never see you again. I knew what you’d do if we had a baby. I knew I’d see you.”

Wayne stood in the shower and thought about the ravine where he and Mandy used to go and wondered if he should have jumped when he had the chance.

He could see Mandy sitting on the sink counter patterned into a thousand pieces by the cloudy fragmented glass of the shower door. He wished he had made her stay in Kentucky, that they’d raised Feather together. He wanted to make her move back with him, or at least have Feather with him. He barely knew Feather, but everything he did for the past four years centered around her. “Can we have tests done?”

“Paternity tests?” Mandy asked.

“Yeah, do you know a doctor around here that’d do them?”

“Well, Feather’s doc could, I guess.”

Wayne paused. He let the shampoo fall into his open eyes, stinging them before he rinsed it out. He’d hitchhiked down with hardly any money. He didn’t have enough to pay for expensive testing.

He stuck his head through the glass. “I guess we’ll have to do it next time. I don’t have the money, and it’s not like you can go up to L.J. and ask him for it.”

She was quiet for a long time. “You sure you want to know?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, I have something for you anyway. If you want to know, just use it.” She disappeared, leaving Wayne in the cooling water. After a minute, she came back with an envelope in her hands. “This is for you. It isn’t all there, but most of it. I was saving it for Feather to go to college because L.J. doesn’t believe in it, says he’s done just fine without it, and how can you argue with that because he has.” She stopped and bit her lip. “I want you to have it back. There’s a lot there, definitely enough for a test.”

“When do you think the doc can do it?” Wayne asked. He rinsed the soap from his tattoo.

The test was a few days later. Wayne had to use part of the money Mandy gave him—Feather’s money—to stay on at the motel. It was the only way he could afford it. When he saw Feather in the doctor’s office, he couldn’t imagine she wasn’t his. Look at her hair, he thought, it’s my color. And her eyes, they’re shaped just like mine. He stared at her, then abruptly walked over and picked her up and squeezed her.

“Mama!” she hollered. Wayne set her down, and walked across the room where he wouldn’t frighten her, but could watch her through the water of a large aquarium.

After they got the test results, he took enough money from the envelope to get a bus back home, then handed the envelope back to Mandy. “Keep it for her. It’s her money really.”

“No, Wayne, I can’t.”

“It’s hers.” He walked off through the sleet headed for the bus that would take him back to Kentucky.

He kept sending money, and every now and then found himself in Alabama in the Motel 6. Sometimes he called Mandy’s number, but no one ever answered. Eventually the number was disconnected. He went back to Kentucky, feeling stupid to be in a state where Feather and Mandy may not even live.

One day Wayne got back, a new guy—Del—started work at the track. Wayne taught him how to cut meat in ways least likely to slice his hands on the bones. New guys always cut themselves a lot more than Wayne, who’d been around the longest except his boss.

When they got off work, Wayne asked if Del wanted to go get a beer.

“Sure, bud.”

On the way out of the track, they took off their sweat-soaked shirts.

Del nodded at Wayne’s chest, “So who’s Feather? Your girlfriend?”

“No.” Wayne looked down at the hay they walked over to get out to the gravel lot where their cars were.

“Oh, ex-girlfriend.”

“No,” Wayne answered, kicking gravel and hay with the toe of his boot. “I guess I’d rather not talk about it.”

“All right man, that’s cool. Painful break up?”

Wayne nodded, and picked a piece of straw out of his boot.

“Yeah, those suck.” Del said. “Thought it wasn’t an ex-girlfriend. Oh man, ex-wife?”

“No.” Wayne paused at his car, and looked around. “Hey man, let’s get that beer tomorrow. I don’t feel like it right now.”

“All right.”

Wayne got into his car, and slowly rolled down the window, rolling each half turn as if the roller were hard to turn, though he had just taken apart the door and oiled it so it glided down easily. He looked at Del, and then said, “Ex-daughter,” rolled up his window and drove away.

Elizabeth Glass holds Masters degrees in Creative Writing and Counseling Psychology. She has received grants from the Kentucky Foundation for Women and the Kentucky Arts Council, and won the 2013 Emma Bell Miles Prize. Her writing has appeared in Still: The Journal; New Plains Review; Writer's Digest; The Chattahoochee Review; and other journals. She lives in Louisville, Kentucky.

March 20, 2015

The Failure of Love and Everything, poem by William Taylor, Jr.

The Failure of Love and Everything

Baby, we are every ticket that didn't win.

We are the the defeated armies of the ages,

the view from every window of every shitty hotel

in every shitty town you can imagine.

We are the need for one more drink

after 2 a.m.

as the heartless bartender says

it's too late, too late,

go home.

We're the wreck on the freeway

the people drive past

and forget,

we're the poster children

for the failure of love

and everything.

Yet even now,

on nights like this,

I can still get drunk enough

to miss you.

March 17, 2015

Lonely Larry, poem by Frank Reardon

LONELY LARRY

Everyday Larry walks into the lumber yard

with his head down due to years of bad posture.

His hair, fake or not, looks like a blond toupee,

and he twiddles his fingers in mad circles

when he speaks. Mona, the cashier,

calls him "Lonely Larry." She says it whenever

he leaves the room. "Lonely Larry, poor-poor,

Lonely Larry." During the day Larry is a lumber

merchandiser and he takes his job very seriously

even if his corduroy pants are pulled up over

his belly button. He looks like a giant Weeble

most days, and he's a massive billowing shit-talker

from years of love lost, everyday. While fastening the Velcro

straps on his gray sneakers, Larry likes to remind

me of his youth, how in his 20s he was a ladies' man,

a sure-fire chick magnet. He says it was

all due to his over-use of cologne and gold chains.

I find it hard to believe, especially since his work apron

has his name painted on it with large purple letters

and bedazzled silver rhinestones, though he's done

a great job convincing himself of his prowess. Whenever Kayla,

the woman with the perfect ass, the woman who can

speak perfect French, says "hi," Larry's

fake deep voice turns high-pitched and nasally.

He's 60, but whenever that French painting

struts by with her big black boots he turns

into himself: quiet, nervous, perverted, the shy little boy.

At night Larry is a quiz show genius, a Game Show Network

lunatic. Sitting in his father's old leather recliner,

he tries to solve puzzles on The Wheel of Fortune

while sucking root beer from a straw. "Buy a vowel!"

he shouts as he twists off the top of an Oreo

so he can lick the cream filling.

"Why won't she buy a fucking vowel!?" he asks

his purple and yellow canary sitting in its brass cage,

but the bird never replies, it just sits

on a perch rapidly moving its head and chirping a song.

Poor-poor Lonely Larry, the game shows are over

and the symphony has gotten so cruel

with night songs that Larry must go under his bed

and pull out the old box with the frayed cardboard cover.

Inside: ancient comic books that he had saved since

he was a child. And with teeth clenched upon bottom lip,

he savors each action packed square,

each crime fighter's heroic action, each word floating

inside its cartoon bubble. The hands are weak, the sweat

is real, the foreboding feeling in the dark pulls

at lost eyes and surrounds him with panic.

Soon Larry will climb into bed. "Gotta get up at 4 a.m.

and do it all over again," he'll whisper to himself.

It's the same thing each day and night, the perfect

hell on earth, relived day after day and night after night.

The perfect assassin with the perfect bullet,

inching closer and closer by the second until it burrows in us all

and plants the great seed of denial.

January 17, 2015

Meth Labs in West Virginia?! You're Kidding.

Usually, when Jennifer McQuerrey Rhyne's truck pulls up to a property, it's the first time neighbors have seen any activity there in weeks.

Even though the decals on her hulking Tacoma read "www.wvmethcleanup.com"—literally spelling out why she is there—she becomes a magnet for anyone looking for information about the former proprietors of the meth cook sites she cleans for a living. Along with a bevy of shady characters, the business offers a window into the changing drug habits of rural, white America.

When I join her for a day on the job in December, Jennifer is standing outside a ground-floor apartment in Clarksburg, West Virginia. Though she hasn't suited up yet, her two associates, Heath Barnett and Joe MuQuerrey—her father—are already dressed head-to-toe in white chemical hazard suits, their faces buried in gas masks. They haul furniture from the apartment into the bed of Jennifer's truck. The door is ajar to reveal the checkerboard tile in the kitchen. Jennifer waits for the mother of the building owner to arrive with payment for the job. More.

January 13, 2015

The World Made Straight

FCAC is still kicking. Lots of content coming, but for right now there's this review by Tirdad Derakhshani of the film The World Made Straight based on the superlative novel by Ron Rash.

'Geography is destiny," Leonard Shuler (Noah Wyle) says in a voice-over at the start of the somber Appalachian tragedy The World Made Straight. As he speaks, the camera takes us across an overgrown piece of mountain in Madison County, N.C., cut along one side by a two-lane road, the other by a dirt-colored river.

For Midwesterners, that means wide spaces; open vistas; possibility, says Leonard. For his neighbors, who live their lives in the overgrown fields, muddy streams, and rough back roads of Appalachia, the world is limited, stifling.

More?

While you're at it, check out the review of Rash's latest in the NYT.

Ron Rash occupies an odd place in the pantheon of great American writers, and you’d better believe he belongs there. He gets rapturous reviews that don’t mean to condescend but almost always call him a Southern or Appalachian writer, and Mr. Rash has said he can hear the silent, dismissive “just” in those descriptions. He also baffles anyone who thinks that great talent ought to be accompanied by great ambition. Mr. Rash has planted himself at Western Carolina University and eluded the limelight that his work absolutely warrants.

October 16, 2014

Final Girl on Appalachia

H/t to Pank.

Why I Stay

Three brown tires are on the bank of the river, like shells would be on the beach of another place. This is not that place.

It is hard to deny some of the beauty of Appalachia: rolling roads, haze on the fields, morning-green hills, horses. Other beauty is tricky. You have to train your eye—or, you have to have a certain eye already.

I don’t believe the broken-down bus mars the sunset. I think it makes it, morning glory twisting around the rims. Pokeberries stain the farmhouse purple; we threw them against its side. There is a kind of beauty in giving up. There is a sort of joy in why the hell not.

After all, there are cans in the weeds. Bones in the woods. Burned-out sheds in the shadows. So: low to the ground, by cigarette butts, I glue on the wall hand-painted leaves.

August 23, 2014

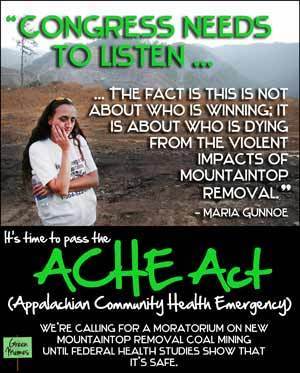

Moving Mountains Tragedy 2014: Stunning Court Denial of Appalachian Health Crisis

The only thing stunning about this is the years-long denial. From Huffington Post's Jeff Biggers.

The only thing stunning about this is the years-long denial. From Huffington Post's Jeff Biggers.

In a breathtaking but largely overlooked ruling this week, a federal judge agreed that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers may disregard studies on the health impacts of mountaintop removal mining in its permitting process, only two weeks after Goldman Prize Award-winning activist Maria Gunnoe wrote an impassioned plea to President Obama to renew withdrawn funding for US Geological Survey research on strip mining operations and redouble federal action to address the decades-old humanitarian disaster.

The prophetic call for immediate federal action by Gunnoe, a community organizer for the West Virginia-based Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition and a long-time witness to the tragedy of mountaintop removal, has never been so timely. "Appalachian citizens are the casualties of a silent "war on people" who live where coal is extracted," Gunnoe wrote the president. "Citizens of all ages are dying for the coal industry's bottom line."

More.

Fried Chicken and Coffee

- Rusty Barnes's profile

- 227 followers