Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 99

November 9, 2014

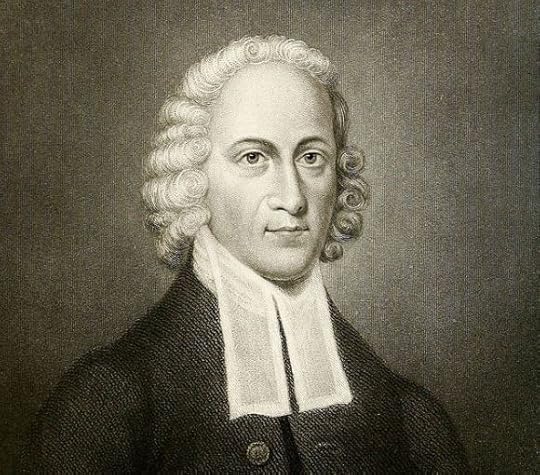

Beyond Hellfire And Brimstone

Jonathan Edwards, the great 18th century American theologian and preacher, exists in the popular imagination mainly as a dour purveyor of God’s judgment, famous for his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Marilynne Robinson rises to his defense, praising his understanding of sin as “a kind of unawakened experience or perception that is blind to the glory of God and therefore to the glory that pervades being”:

For Edwards, sin was the state everyone was in, in the absence of a conversion experience, which was a kind of religious ecstasy that began with a profound awareness of guilt and a sense of utter dependency on God’s grace. Religion without conversion was almost a kind of Pharisaism, the enactment of faith and virtue without the substance of either. It was, at the same time, where the predisposition to conversion was formed. Edwards meant by his preaching and teaching to lift his hearers into the realm of spiritual light, where they would be capable of true faith, true hope, true love. They would be raised to a heightened esthetic experience, beside which the manifest natural glory of the world would seem a poor thing. Minus the theological frame, the same impulse to apprehend reality through a vision of it that is both higher and truer is present in much American poetry, from Whitman to William Carlos Williams and Wallace Stevens.

Again, for Edwards as for Emerson, this was not contempt for the world but transcendence of a kind that allowed the world and being itself to be seen in its real glory.

Given his very fixed association with hellfire preaching, it is important to remember that it was not particular transgressions that interested Edwards finally, though of course from the pulpit he deplored failures of honesty and charity. Nor was he much concerned with meritorious acts, since these were equally beside the point in the matter of personal salvation. Salvation was for him a revolution of consciousness that opened on an overwhelming sense of the beautiful, the glory of God in all its manifestations. In Edwards’s view, fallenness, the natural state of any human being, as blindness, takes no specific form as behavior and is not to be mitigated by any act of will. But the ontological nearness of humankind to God means that, through grace, perception of the purest, highest and truest kind, itself a kind of ecstasy, can be enjoyed by them, eternally and in this life.

(Image: An 1855 engraving of Edwards, via Wikimedia Commons)

November 8, 2014

The Best Hangover In Fiction?

A Dish reader flags the above video, in which Boris Johnson nominates Kingsley Amis’ famous account from Lucky Jim. Here’s the passage in question:

Dixon was alive again. Consciousness was upon him before he could get out of the way; not for him the slow, gracious wandering from the halls of sleep, but a summary, forcible ejection. He lay sprawled, too wicked to move, spewed up like a broken spider-crab on the tarry shingle of the morning. The light did him harm, but not as much as looking at things did; he resolved, having done it once, never to move his eyeballs again. A dusty thudding in his head made the scene before him beat like a pulse. His mouth has been used as a latrine by some small creature of the night, and then as its mausoleum. During the night, too, he’d somehow been on a cross-country run and then been expertly beaten up by a secret police. He felt bad.

Do readers have a better suggestion? For those unfamiliar with Amis’s novel, there might be no better introduction than this essay from Hitch, which particularly emphasizes what makes the book so funny:

I happened to be in Sarajevo when Kingsley Amis died, in 1995. I was to have lunch the following day with a very clever but rather solemn Slovenian dissident. She knew that I had known Amis a little, and she expressed the proper condolences as soon as we met. Feeling this to be not quite sufficient, however, she added that the genre of “academic comedy” had enjoyed quite a vogue among Balkan writers. “In our region zere are many such satires. But none I sink so amusing as ze Lucky Jim.”

This, delivered with perfect gravity in the lugubrious context of the Milosevic war, made me grin with inappropriate delight. How the old buzzard would have gagged, with mingled pride and disdain, at the thought of being so appreciated by a load of Continentals—nay, foreigners. And what the hell can his masterpiece be like when rendered into the Serbo-Croat tongue?

Just try to suggest a more hilarious novel from the past half century. Something by Joseph Heller? Terry Southern? David Lodge or Malcolm Bradbury? Yes, the Americans can be grotesque and noir; and the Englishmen have their mite of irony. (In fact, the academic comedy is now a sub-genre of Anglo-Americanism.) But even so. The late Peter de Vries—much admired by Amis for his Mackerel Plaza—depended too much on the farcical. No, the plain fact is that Amis managed in Lucky Jim (1954) to synthesize the comic achievements of Evelyn Waugh and P. G. Wodehouse. Just as a joke is not really a joke if it has to be clarified, I risk immersion in a bog of embarrassment if I overdo this; but if you can picture Bertie or Jeeves being capable of actual malice, and simultaneously imagine Evelyn Waugh forgetting about original sin, you have the combination of innocence and experience that makes this short romp so imperishable.

Face Of The Day

Lori Zimmer captions the work of Nick Gentry:

With the age of technology advancing faster than we can possibly keep up with, we are left with obsolete media. Film cameras have been replaced with digital capture and USB drives render floppy disks useless. As an artist, Gentry finds beauty in these forgotten remnants, like the rolls of exposed 35 mm film he finds in abundance in thrift stores and secondhand sales, or receives from donors.

His effort to give new life to the media that are now obsolete has created inspiration for a beautiful body of work, which is given greater depth than if simply painted on canvas. Gentry paints many of his portraits with a direct gaze, which almost summons to viewer to look deeper into the work.

Explore more of Gentry’s work here, here, and here.

“What Exactly Is An Unusual Sexual Fantasy?”

That’s the refreshingly straightforward title of a recent study in the Journal of Sexual Medicine. Andy Cush sums up its findings this way: “The bad news: you’re probably a freak. The good news: everyone else is, too”:

Researchers from University of Montreal presented 799 men and 718 women—85.1 percent of whom identified as heterosexual, 3.6 percent homosexual, and 11.3 percent somewhere in between—with a long list of statements regarding fantasy scenarios, asking them to rate their agreement with each on a scale of one to seven. Anything rated over three was counted as a fantasy.

Some notable trends: women were far more likely to fantasize about sex with strangers or in particular locations, while men were more interested in oral and anal, as well as sex with acquaintances. Men also tended to describe fantasies that weren’t on the list more vividly and expressed more interest in actualizing their fantasies than women.

Jessica Orwig has more:

Interestingly, both sexes were about equal when it came to participating in group sex, although more men reported wanting to have an active versus passive role during group sex. When it came to whom the subjects thought about, men reported fantasizing more about people they were not currently involved with. Of particular interest to the researchers was the high number of fantasies that were mostly unique to men, for example, fantasizing about anal sex and watching their partner have sex with another man. “Evolutionary biological theories cannot explain these fantasies,” researcher [Christian] Joyal said.

Check out the researchers’ full chart of common and rare fantasies here.

Supper For Socialists

In a wide-ranging essay about food culture, Jeff Sparrow makes the case that takeout meals have an ideological bent:

“The abolition of the private kitchen will come as a liberation to countless women,” proclaimed August Bebel in his extraordinarily influential 1879 Woman and Socialism (a book that went through 53 German editions in his lifetime). “The private kitchen is as antiquated an institution as the workshop of the small mechanic. Both represent a useless and needless waste of time labor and material.”

Collective cooking as liberation to the tyranny of the private oven remained a progressive orthodoxy into the first half of the 20th century. The Bolshevik Alexandra Kollontai explained: “Instead of the working woman having to struggle with the cooking and spend her last free hours in the kitchen preparing dinner and supper, communist society will organize public restaurants and communal kitchens.” …

The rhetoric might sound antiquated but, in a sense, we now take for granted Bebel’s communal kitchens, albeit in private form. The ubiquity of cheap, almost instant takeaway meals represent a transformation almost unimaginable to the 19-century women whose daily routine still involved plucking fowls and skinning rabbits and other tasks now only performed in factories.

Mental Health Break

What’s In A Title?

F. Scott Fitzgerald almost went with Trimalchio in West Egg; Edward Albee got Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? from bathroom graffiti in a Greenwich village bar. In a piece for The Millions, Chloe Benjamin to five authors about how they came to name their novels. Among them is Matthew Thomas, who found the title for his book We Are Not Ourselves in the pages of King Lear:

While re-reading Lear in preparation to teach it, I came to the line in Act 4, Scene 2, where Lear is wondering why Cornwall won’t appear, even though he’s been ordered to. To explain away the offense to his ego, Lear says, “Infirmity doth still neglect all office/Whereto our health is bound”—i.e., sickness prevents us from doing the duties we’re required to do when healthy. The next line elaborates on this theme: “We are not ourselves/when nature, being oppressed, commands the mind/to suffer with the body.” Lear justifies Cornwall’s flouting of his authority by appealing to the universal experience of being beholden to our bodies: when the body isn’t working, the mind doesn’t work perfectly either. I found rich resonance in the idea of locating both the mind and the body in Lear’s formulation in the brain, so that the body that isn’t working is the mind, in fact — and then positing the mind in Lear’s formulation as what we think of as the spirit, the soul, the personality. When the brain isn’t working at its optimal best — when there’s an obstruction of function through illness, or a fixation or obsession that springs from traumatic early childhood experiences — the animating spirit of the person, what we think of as personality, is impaired as well.

The phrase struck me immediately as being at the heart of my concerns in the book.

We Are Not Ourselves suggests characters who are not at their best, who by dint of circumstances are not allowed to be themselves. It also suggests that we’re always learning and evolving, that we’re works-in-progress. We are not ourselves yet, in a sense; there’s hope in that. In a different vein, we are not reducible to whom we appear to be in our biographies. We contain multitudes in our rich internal lives that our lived lives don’t reveal. Another resonance for me is that we need each other to experience the full flowering of our humanity and our greatest happiness. We are not only ourselves; we are not islands unto ourselves. I liked that the phrase opened up fields of interpretation that would extend beyond the more circumscribed concerns of my original title, so I grabbed it and didn’t look back. As soon as I knew it was the title, it was as if it had been the title all along.

The Art Of Opulence

This week, “Chariot,” a sculpture by Alberto Giacometti, sold for $100,965,000. Felix Salmon marvels that, because “Chariot” comes from an edition of six, “when Giacometti made this sculpture, he didn’t create a hundred million dollars in present-day value; he created six hundred million dollars“:

It’s entirely rational to think that value goes down as edition size goes up—that if a sculpture is in an edition of six, then it will be worth less than if it

were unique or in an edition of two. But the art market is weird, and doesn’t work like that—or, at least, it doesn’t work like that anymore, since it has become an extension of the luxury-goods market. In order for an artist to have value as a brand, he has to have a certain level of recognizability—and for that he needs a critical mass of work. Artists with low levels of output (Morandi, say) generally sell for lower prices than artists with high levels of output—the prime example being Andy Warhol. The more squeegee paintings that Gerhard Richter makes, the more they’re worth.

In the case of “Chariot,” the other versions of the sculpture don’t dilute the value of the art so much as ratify it. Just look at the list of institutions that own a copy: the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, the National Gallery in Washington, the (wonderful) Giacometti Museum in Zurich, and MoMA. (The other two copies, including the one Sotheby’s just auctioned, remain in private hands.) You might want to own the “Desmoiselles d’Avignon,” but you can’t, because it’s in MoMA. With “Chariot,” however, you can own a sculpture that is treasured, and owned, by the world’s greatest museums. That makes it more valuable, not less. At the margin, increasing an edition size can increase the value of a work, so long as the other versions end up in high-prestige collections.

(Image of “Chariot” in Washington, D.C. via Flickr user Jerk Alert Productions)

A Closer Look At Larkin

Largely unimpressed by James Booth’s efforts “to present a warmer, kinder, more admirable Larkin” in his new book, Philip Larkin: Life, Art, and Love, Jonathan Farmer finds the poet something of a misanthrope:

His personality seems to have been, to a large extent, a kind of jerry-rigged response to his awkwardness, and it’s a measure of his extraordinary inventiveness that his manufactured persona endeared him to so many who knew him in so many ways. The poems, at their frequent best, transform those same impulses into art with even greater skill. …

Andrew Motion, whose earlier biography—both more critical of and more sympathetic toward Larkin—will thankfully remain the definitive work, has written of the “number of moments” in Larkin’s work which “manage to transcend the flow of contingent time altogether.” Those moments rarely involved other people. Famously death-obsessed, Larkin seems to have craved such freedoms, but they didn’t come easily to him, probably for the same reasons he so needed them: Life scared him, too. Too long withheld from the company of people outside his family, Larkin sharpened his wit in learning how to please others, but as with so many who invest so much in performing, he rarely found pleasure in others beyond his ability to please them. Company exhausted him, even though he grew lonely in its absence.

Peter J. Conradi, on the other hand, appreciates the complexity of Booth’s portrait:

Booth’s psychology is subtler than Motion’s and more convincing. His achievement is to paint a satisfying and believably complex picture. Larkin the nihilist also wrote: ‘ The ultimate joy is to be alive in the flesh.’ Larkin the xenophobe loved Paris and translated Verlaine. Larkin the racist wrote the wonderful lyric ‘For Sidney Bechet’ and dreamt of being a negro. The Larkin who wrote ‘They fuck you up, your Mum and Dad’ loved his own parents.

As for Larkin the misogynist, it is mysterious how the character painted by Motion could have had any love life at all, let alone a highly complex and fulfilling one. True, Larkin himself once wrote incredulously and comically of sex as ‘like asking someone else to blow your nose for you’: he sometimes experienced a Swiftian horror at being incarnate. Yet he was also very attractive to women and for excellent reasons: he liked women and was a tolerant, patient listener and a wise soulmate. He regretted never marrying. In one mood he indeed described his life to Motion as ‘fucked up’ and ‘failed’ as a result. But this was one mood; and he had others.

And Jeremy Noel-Tod notices that, whatever his churlishness, Larkin managed to have a robust, if complicated, love life:

Outside the precious space of his writing, his complicated, indecisive love life kept him busy. Booth provides new material drawn from interviews with the various women involved, all of whom are cited in support of the view that Larkin the man has been maligned: ‘Typically, they found him “witty”, “entertaining”, “considerate” and “kind”.’ These qualities are abundantly present in the poems too. But so is unkindness, and the writing wouldn’t be as acute as it is without that unsentimental self-knowledge.

Previous Dish on Larkin here.

It’s The Pain Talking

In a review of Joana Bourke’s The Story of Pain, Arthur Holland Michel considers how we find words for our suffering:

We “can express the thoughts of Hamlet,” wrote Virginia Woolf in 1930, “but let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry.” Even acute agony is so shifty, vague, embodied, and (at times) transcendental, it defies meaningful description. Stub your toe and it’s hard not to be hyperbolic, if not blasphemous. People say a pain “feels like getting stabbed,” even if they have never been stabbed and therefore have no idea what it actually feels like to be stabbed. …

People in Japan have “musk deer headaches,” and a hurting person in India might invoke “parched chickpeas.” The British “splitting headache!”—which was my mother’s go-to when we made a fuss—is no less peculiar. When trying to describe my shingles, I settled, in my delirium, to calling it “a jaunty hat of pain.” My uncle, who is fighting (bravely) against Lymphoma, says he feels that a cuckoo is trapped in his body, trying desperately to escape. I’m pretty sure he has never swallowed a live bird, and yet, like so many of Bourke’s sufferers, that’s as close as he can get to describing what he feels. As she points out, these descriptions, however bizarre and hyperbolic, still matter. By verbalizing how a pain feels, we are informing the way we feel it.

On a related note, Alana Massey movingly relates the challenge of articulating her experience of depression:

The English language has a great deficit in words to describe the impenetrable hopelessness that mental illness visits upon those afflicted with it. I’ve spent embarrassing amounts of time seeking out words in other languages that give form and substance to this lifetime of experiences. Germans have Verzweiflung, it is the direct translation of despair but it is aslo accompanied by fear and pain. The Czech litost is the torment of suddenly seeing the extent of one’s own misery. Toska is what Nabakov said could never be fully expressed in English words and described as “a sensation of spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause.” …

[E]ven in possession of a reasonably sophisticated grasp of the English language, it is exceedingly rare that I speak of the ever-present sense of dread at having to go about a day, day after day, in more than a few words. Clever metaphors and well-crafted sentences have many merits but few palliative functions. Literary history is littered with the corpses of suicidal writers whose extensive catalogs dedicated primarily to pain demonstrate that to articulate suffering is not to be relieved of it. And so instead of giving a name or a shape to it with words, I have communicated suffering with personal absences and incomplete gestures and tasks since I was very small.

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 153 followers