Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 396

December 30, 2013

Mental Health Break

Turmoil In Turkey, Again, Ctd

Humeyra Pamuk and Orhan Coskun expect Erdogan to weather the corruption scandal:

Investors are nervous and the lira currency has swooned. But the scandal has only brought out the fight in Erdogan, who has consistently said that the entire affair is a foreign-backed plot against him. He has sacked police officers including the Istanbul police chief, exchanged diatribes with a powerful cleric and steadfastly insisted he has done nothing wrong. The document naming his son was just another example of the conspiracy, he said: “If they try to hit TayyipErdogan through this, they will go away empty-handed. Because they know this, they’re attacking the people around me.”

So far, opinion pollsters predict that support for Erdogan’s AK party, which enjoys wide support in Istanbul and the conservative countryside, has probably fallen by a few percentage points but still remains over 40 percent. That is hardly enough of a slide to force it out of power. The last election saw it win more than two thirds of the seats in parliament with 50 percent of the vote, an unprecedented success. Still, one senior official in Erdogan’s AK party predicted the next general election, due in 2015, could be brought forward to early next year “if events take a dramatic turn”, a sign that the party is revising its calculations to contain the fallout.

Dexter Filkins links the crisis to Erdogan’s increasingly paranoid leadership:

There isn’t much doubt that something called “the deep state” actually existed in Turkey, and that it used violence and intimidation to enforce the secular state enshrined by Turkey’s founder, Mustafa Kemal, or Atatürk. But the Ergenekon investigation, along with its sister case, called Sledgehammer, rapidly evolved into something much more pernicious: a campaign to crush Erdoğan’s political opposition.

The Ergenekon and Sledgehammer prosecutions were built on mostly fabricated evidence. In case that didn’t work, Erdoğan embarked on an aggressive campaign to silence anyone who might criticize him, most notably the press. Just last week, the Committee to Protect Journalists reported that Turkey had forty reporters behind bars, more than any other country in the world. All this worked for a while, in no small part because Erdoğan faced almost no criticism from the West. The Obama Administration, grateful for an ally in an otherwise unfriendly part of the world, largely gave the Prime Minister a pass. Erdoğan, who is planning to run for President in 2014, seemed destined to stay in power for years to come.

But then it all unravelled. It’s not clear why Erdoğan and Gülen ["the leader of a far-flung Islamic order"] are splitting now, but, according to some reports, the roots may lie in disagreements over foreign policy and how to deal with the country’s Kurdish minority. Among other things, the Gülenists oppose Erdoğan’s arming of rebels in Syria and the cooling of the Turkish government’s long-standing friendship with Israel. The Erdoğan-Gülen break also follows Erdoğan’s brutal suppression of anti-government protests that swept the country earlier this year.

Brent E. Sasley further explores Erdogan’s struggle:

It is one part tug-of-war between the two main elements of Turkey’s Islamist-conservative movement, the AKP and the Gülenist movement (also known as Hizmet, or the Service), one part Erdoğan responding to what he sees as illegitimate criticism of his rule. At this point there is no viable substitute to either the AKP or to Erdoğan himself (though President Abdullah Gül is touted as a possible candidate). What is more likely is the undermining of Turkey’s political institutions to the point that the country’s politics becomes as dysfunctional as it was in the pre-AKP era. The institutions that have suffered most directly as a result of Erdoğan’s effort to shut down the investigations are the judiciary and the police, but the civil service and the media have also been victims of Erdoğan’s tenure. So, too, has the entire political system that, in a democracy, depends upon a loyal opposition able to safely critique the government and suggest alternatives.

Alexander Christie-Miller has more on the Gülenist movement and its role in Turkish politics over the past decade:

Drawn from the teachings of the reformist Sufi thinker Said Nursi, who died in 1960, Gulen’s followers espouse engagement with the West, interfaith dialogue, self-advancement, and a dash of Turkish nationalism, and emphasize the importance of education in the sciences. It is believed to have between 3 million and 6 million followers worldwide, and runs a network of schools in more than 130 countries. In the US, it runs one of the largest networks of charter schools – purportedly secular – with links to more than 100 schools. In Turkey, it controls a media and business empire that includes the newspaper Zaman, the country’s highest-selling daily.

Gulen followers, who were often clean-shaven, Western-educated, and English-speaking, defied the stereotypes of Islamists in Turkey during the 1990s and early 2000s, which some analysts believe allowed them to enter the judiciary and police without attracting the attention of the secularist establishment. Leaked video footage of one of Gulen’s sermons from 1999 laid out this strategy explicitly: “You must move in the arteries of the system without anyone noticing your existence until you reach all the power centers,” he said. “You must wait until such time as you have gotten all the state power, until you have brought to your side all the power of the constitutional institutions in Turkey.” Gulen-allied prosecutors – in some cases the same individuals who launched the current corruption probe – were widely believed to be the driving force behind two mass trials that effectively broke the power of the military, which historically has seen itself as the protector of Turkey’s secular governing model.

Howling About Wall Street

Yglesias considers the politics of the new Scorsese film, The Wolf of Wall Street:

This kind of fraud is a real thing, and it especially happens when you have a prolonged boom (as we did in the 1980s and 1990s stock market), but I think that if you’re a major Wall Street executive or work for one of the bank lobbies you have to be very happy with this film. Indeed, very happy in general that Hollywood keeps churning out stories with this kind of focus. Everything Stratton Oakmont is shown as doing has been illegal for years and the enforcement, though imperfect, is real. What’s more, like the more recent story of Bernie Madoff, they weren’t just perpetrating frauds they were a whole fake firm. These guys in this movie aren’t real Wall Street guys. They have tacky outer-boroughs accents and no education. The idea that the FBI and the SEC need to do a more rigorous job of keeping sleazy drug-addled deviants from posing as real stock brokers and investment advisers is the most comfortable possible reform proposal for the real Titans of Finance, most of whom are perfectly respectable people with respectable accents and real degrees from prestigious universities. You have to rein them in not with exciting wiretaps but with boring regulations on leverage and liquidity.

David Edelstein faults the movie for glamorizing crime:

The Wolf of Wall Street is three hours of horrible people doing horrible things and admitting to being horrible. But you’re supposed to envy them anyway, because the alternative is working at McDonald’s and riding the subway alongside wage slaves. What are a few years in a minimum-security prison — practically a country club — when you can have the best of everything?

David Denby finds that Scorsese’s latest was “made in such an exultant style that it becomes an example of disgusting, obscene filmmaking”:

As the critic Farran Smith Nehme pointed out to me, one of the filmmakers’ mistakes was to take Jordan Belfort’s claims at face value. In his memoir, Belfort presents himself as a very big deal on Wall Street. The movie presents him the same way—as a thieving Wall Street revolutionary—whereas, in fact, he was successful but relatively small time. From the beginning, “Wolf” feels inflated, self-important. DiCaprio’s Jordan Belfort comes right at us, narrating directly to the camera, like a low-rent Richard III. He takes us into his confidence, pitching his life story to us—we might be one of his clients. As he talks, “Wolf” develops the rise-and-fall shape of a gangster movie, like Scorsese’s marvellous “GoodFellas,” which, too, is narrated by its hero, played by Ray Liotta. But we never develop any empathy for Jordan, nor do we identify with him, as we did with Liotta’s Henry Hill. The narration has such an unremittingly boastful tone that the response is, often, “What a jerk.”

Michelle Dean’s related take:

The Wolf of Wall Street suffers from a more complicated and more interesting flaw: its inability to definitively puncture Jordan Belfort’s self-mythology. I don’t just mean, as David Denby [pointed out], that Belfort was no big deal as far as Wall Street was concerned. It’s certainly true that Belfort’s crime was small in the amount. And there is a real lie there in the way this movie’s getting marketed and talked about, in the way we’re expected to believe this movie is about “what’s wrong with Wall Street.” In fact the kind of simple securities fraud Belfort committed isn’t really the canker in the rose, these days. The evil’s of a more banal kind now, involving structured financials so devoid of any reality that it’s hard to even say who or what they’re trading. I could explain but it would be super-nerdy and well, movies are not economic history classes.

But that sort of factual elision points to the larger flaw. In my experience, people on Wall Street have a habit of believing that what they do is Important, though they can’t ever tell you how or why. They are lying to themselves as a first principle. And every other statement they make needs to be evaluated in that context.

Dana Stevens joins the disapproval:

Unredeemed jerks can make for transfixing movie heroes (and DiCaprio has played not a few such characters, from the slippery trickster of Catch Me If You Can to the shirt-tossing profligate of The Great Gatsby). But Scorsese and Terence Winter (the Emmy-winning Sopranos writer who adapted Belfort’s memoir for the screen) overestimate the audience’s ability or desire to watch Leo misbehave. The story’s relentless, unvarying rhythm—malfeasance, consumption, more malfeasance, more consumption—leaves the audience drained and annoyed.

Christopher Orr, on the other hand, liked the film:

Yes, Martin Scorsese’s new feature is undeniably topical: the story of a rogue Wall Street trader, Jordan Belfort, who made himself and his partners fabulously wealthy at the expense of the broader American public and got off—even after multiple fraud convictions—nearly scot-free. But the film displays almost no interest whatsoever in Belfort’s victims, and it is extravagantly incurious regarding the mechanisms by which he took their money. If this is a message movie, it’s one that features a message suitable for a cue card.

None of which, incidentally, is intended as an indictment. The Wolf of Wall Street is a magnificent black comedy, fast, funny, and remarkably filthy. Like a Bad Santa, Scorsese has offered up for the holidays a truly wicked display of cinematic showmanship—one that also happens to be among his best pictures of the last 20 years.

Dueling Rulings On The NSA

Judge Richard Leon and Judge William Pauley disagree about legality of the metadata collection program. Andrew Cohen sees the rulings as an example of the subjectivity of law:

Although the two rulings involve different plaintiffs, Judge Pauley’s opinion reads as a pointed response to Judge Leon’s ruling of 10 days earlier. In fact, I suspect the two rulings will soon be used side by side in law schools to illustrate how two reasonable jurists could come to completely different conclusions about the same facts and the same laws. And that, of course, says a great deal about the nature of the NSA’s program itself and its symbolic role in the conflict America faces as it teeters back and forth between privacy and security.

Taken together, these two manifestos represent the best arguments either side so far has been able to muster. If you trust the government, Judge Pauley’s the guy for you. If you don’t, Judge Leon makes more sense. That two judges would hold such contrasting worldviews is either alarming (if you believe the law can be evenly applied) or comforting (if you believe that each individual judge ought to be free to express his conscience). In any event, taken together, the two opinions say a lot about nature of legal analysis. The judge who gets overturned on appeal here won’t necessarily be wrong—he’ll just not have the votes on appeal supporting his particular view of the law and the facts. In the end, you see, there is no central truth in these great constitutional cases that rest at the core of government authority; there is just the exercise of judicial power.

Amy Davidson is alarmed at the wide berth Pauley seems to grant the administration:

[I]f Pauley’s opinion offers a single instruction for the N.S.A, it is this: go big.

The more people whose data was swept up, the less this judge apparently thinks he has to say about it. Reading his fifty-four-page opinion, one wonders whether, if the intelligence community could only find a way to violate every single American’s rights, and tell a story about how that protected them, he would look around and find that no one had been hurt. “This blunt tool only works because it collects everything,” he writes. While briefly acknowledging that “unchecked” it could violate civil liberties, he is quite satisfied with the checking in place now. To let the A.C.L.U. challenge the N.S.A.’s collection of its phone records on statutory grounds (that is, by arguing that the Patriot Act was being misused) would be “an absurdity”—absurd, to his mind, because Congress didn’t intend for ordinary Americans to know about this, and because there are so very many of them: “It would also—because of the scope of the program—allow virtually any telephone subscriber to challenge a section 215 order.”

Justin Elliott notices that the evidence Pauley cited from the 9/11 Commission Report isn’t actually in the report:

In his decision, Pauley writes: “The NSA intercepted those calls using overseas signals intelligence capabilities that could not capture [Khalid] al-Mihdhar’s telephone number identifier. Without that identifier, NSA analysts concluded mistakenly that al-Mihdhar was overseas and not in the United States.” As his source, the judge writes in a footnote, “See generally, The 9/11 Commission Report.” In fact, the 9/11 Commission report does not detail the NSA’s intercepts of calls between al-Mihdhar and Yemen. As the executive director of the commission told us over the summer, “We could not, because the information was so highly classified publicly detail the nature of or limits on NSA monitoring of telephone or email communications.” To this day, some details related to the incident and the NSA’s eavesdropping have never been aired publicly. And some experts told us that even before 9/11 — and before the creation of the metadata surveillance program — the NSA did have the ability to track the origins of the phone calls, but simply failed to do so.

Peter Margulies, on the other hand, supports Pauley’s ruling, pointing out that Congress had to have known what it was doing when it authorized and reauthorized the PATRIOT Act:

As Judge Pauley indicates, Congress clearly understood the threat posed by Al Qaeda’s ability to develop lethal plots in a “decentralized” fashion. Neutralizing Al Qaeda’s asymmetric advantage, Judge Pauley finds, requires that the government have the ability to connect “fragmented and fleeting communications.” Without the “counter-punch” supplied by metadata collection, the government risks ceding the long-term initiative to Al Qaeda and associated forces. Allowing the concept of relevance to evolve with the shifting terrorist threat was an eminently sensible strategy for Congress in 2006, when it added the relevance standard.

As Judge Pauley points out, any doubt about Congress’s calculus is extinguished by Congress’s reauthorization of Section 215 in 2010 and 2011, when members of Congress had the twin benefits of, (1) access to documents that described the metadata program, and, (2) the public criticism of the metadata program by senators Wyden and Udall, who warned (in Wyden’s words) of the “discrepancy between what most Americans believe is legal and what the government is actually doing under the Patriot Act.” Judge Pauley asserts that these two sources would place any legislator not in a coma on notice that the NSA and the FISC had broadly interpreted the statutory relevance standard. Indeed, Judge Pauley describes as “curious” Wisconsin representative James Sensenbrenner’s claim that he had no inkling of the metadata program before the Snowden disclosures. Judge Pauley bases his skepticism on Sensenbrenner’s receipt, as a Judiciary Committee member, of summaries of FISC decisions, the decisions themselves, and access to government briefings and white papers. Congress could not have ensured knowledge of the metadata program by the American public, Pauley explains, without disclosing the program’s operation to our adversaries. Congress reasonably concluded, Pauley intimates, that this disclosure posed an unacceptable risk to national security.

Jeff Jarvis wants to change the terms of the debate:

I see some danger in arguing the case as a matter of privacy because I fear that could have serious impact on our concept of knowledge, of what is allowed to be known and thus of freedom of speech. Instead, I think this is an argument about authority – not so much what government (or anyone else) is allowed to know but what government, holding unique powers, is allowed to do with what it knows. … So what we should be restricting – with legislation and open oversight by courts, Congress, the press, and ultimately the people – is the NSA’s ability to seek and use information against anyone (citizen or foreigner) without documented suspicion of a crime, due process, and a legal warrant.

Meanwhile, the latest revelation of the NSA’s info-sucking operation involves Microsoft crash reports:

One example of the sheer creativity with which the TAO [Office of Tailored Access Operations] spies approach their work can be seen in a hacking method they use that exploits the error-proneness of Microsoft’s Windows. Every user of the operating system is familiar with the annoying window that occasionally pops up on screen when an internal problem is detected, an automatic message that prompts the user to report the bug to the manufacturer and to restart the program. These crash reports offer TAO specialists a welcome opportunity to spy on computers. … The automated crash reports are a “neat way” to gain “passive access” to a machine, the [NSA internal] presentation continues. Passive access means that, initially, only data the computer sends out into the Internet is captured and saved, but the computer itself is not yet manipulated. Still, even this passive access to error messages provides valuable insights into problems with a targeted person’s computer and, thus, information on security holes that might be exploitable for planting malware or spyware on the unwitting victim’s computer.

Although the method appears to have little importance in practical terms, the NSA’s agents still seem to enjoy it because it allows them to have a bit of a laugh at the expense of the Seattle-based software giant. In one internal graphic, they replaced the text of Microsoft’s original error message with one of their own reading, “This information may be intercepted by a foreign sigint ["signals intelligence] system to gather detailed information and better exploit your machine.”

The Carnage In Russia

More than 30 people are dead and dozens injured after back-to-back suicide bombings, possibly by Islamists from the Caucasus, on Sunday and Monday in the Russian city of Volgograd, which experienced a similar attack in October. Josh Marshall passes along CCTV video of one of the bombings:

Daisy Sindelar ponders the significance of the target:

Volgograd Oblast, the site of a massive purge of 1980s-era Communist authorities, is still viewed as one of Russia’s most corrupt regions. It is unclear, however, what bearing that might have on its sudden terrorist appeal. Other possibilities include the fact that the city is set to serve as a host during the 2018 soccer World Cup, or the fact that Volgograd, formerly known as Stalingrad, is the site of one of the bloodiest World War II battles and a critical turning point in the war. Writing on the website of the Carnegie Moscow Center, director Dmitry Trenin notes that the city, “a symbol of Russia’s tragedy and triumph in World War II, has been singled out by the terrorists precisely because of its status in people’s minds.” Dmitry Malashenko, a Caucasus expert with Carnegie Moscow, adds that ultimately, Volgograd may simply be a convenient insurgent testing ground. ”It’s clear there’s some kind of smooth-functioning system [in Volgograd] that suits someone’s purposes. Whether that someone is an organization, locals, or people from outside, we don’t know. But the fact that there have been three attacks in a row in one region — excuse me, but it’s a slap in the face of our authorities,” Malashenko said.

Fred Weir relays local concerns that this event is just an opening act:

Russian media reports suggest that Sochi itself, garrisoned with around 40,000 special police and protected by an array of high-tech security measures, as well as the capital city of Moscow, may have been made relatively impregnable to terrorist infiltration. But scores of other large Russian cities, such as Volgograd, have received less attention and clearly remain vulnerable. … Andrei Soldatov, editor of Agentura.ru, an online journal that studies the security services, warns that the two Volgograd attacks in recent months demonstrate that terrorists from the turbulent north Caucasus have the capability to strike repeatedly at major Russian targets. ”The real fear is that these Volgograd bombings could be diversionary attacks,” he says. “This has happened before, we know the terrorists use such tactics. If they are planning something big, attacks like this can distract the security forces, make them divert resources from the main target, and generally sow uncertainty everywhere. . . They clearly have the ability to strike beyond the north Caucasus region, and the people to carry it out. There is no reason to assume that Sochi and Moscow are safe, just because they’re hitting Volgograd,” he says.

But Peter Weber doubts that the bombings will interfere with the upcoming Sochi Olympics:

It’s hard to imagine how Russia could lock down Sochi any further. Starting Jan. 7, only officially registered vehicles will be given access to Sochi and only visitors with special passes will be allowed into the region. Russia has spent months sweeping neighborhoods and targeting potential attackers in the North Caucusus and across the border in Georgia. ”Sochi will be turned into a veritable fortress,” says Leonid Bershidsky at Bloomberg View. Putin will deploy all the resources of Russia’s formidable intelligence and counterterrorism apparatus to make sure Sochi goes off without a hitch. And Bershidsky adds, “Law enforcement chiefs know Putin won’t forgive them for allowing anyone to mess with an Olympic showcase that has cost $48 billion to stage.” …

Sochi and the people who travel there for the Games may be safe — or as safe as humanly possible. Still, if extremists continue to bomb train stations and other public transportation in Russia, enough people could decide to skip the Olympics to mar the Sochi Games with half-empty stadiums. Perhaps even a few countries will sit out this Winter Olympics. But here’s how the Volgograd bombings may actually help Putin: So far the Western coverage of the Games has been mixed with protests over Russia’s anti-gay laws. President Obama is pointedly sending over a delegation with two openly gay athletes, for example. Russia is already calling for international solidarity, and if the focus of the Games shifts to thwarting terrorism, history tells us that terrorism threats trump just about every other issue. After all, fighting Islamist terrorists is one of the few things Putin’s Russia and Obama’s America have in common.

Who Was Behind Benghazi?

Eli Lake contests the NYT’s conclusion that al Qaeda was not responsible:

Some fighters who attacked the U.S. diplomatic compound and CIA annex in Benghazi are believed to be from a group headed by a former top lieutenant to Ayman al-Zawahiri, the current leader of al Qaeda. When Egyptian authorities raided the home of Mohammed al-Jamal, who was an operational commander under al-Zawahiri’s terrorist group in the 1990s known as Egyptian Islamic Jihad, it found messages to al Qaeda leadership asking for support and plans to establish training camps and cells in the Sinai, creating a group now known as the Jamal Network. In October, the State Department designated Jamal Network as a terrorist group tied to al Qaeda. The Wall Street Journal was the first to report the participation of the network in the Benghazi attacks, and the group’s participation in the attacks has also been acknowledged in the Times. The New York Times Benghazi investigation makes no mention of the Jamal Network in their piece.

Blake Hounshell doubts this will ever be settled:

There’s a long-running debate among experts about whether al Qaeda is more of a centralized, top-down organization, a network of affiliates with varying ties to a core leadership or the vanguard of a broader movement better described as “Sunni jihadism.” As Clint Watts, a counterterrorism analyst formerly with the FBI, writes: “There are lots of militant groups around the world which host members that fought in Iraq or Afghanistan or support jihadi ideology. But that doesn’t mean they are all part of al Qaeda.” For instance, is Ansar al-Sharia, an extremist group that everyone agrees had a presence at the Benghazi attack site, an al Qaeda affiliate? Some, including Issa and Rogers, say it is; others insist it isn’t. To make matters more confusing, there are at least two Ansar al-Sharia groups in Libya—one in Benghazi and one in Derna, a city to the east—and dozens of other extremist groups. What about Abu Khattala, the U.S. government’s lead suspect and the central figure of the Times story? He evidently shares a jihadist outlook—but Kirkpatrick found no ties between Abu Khattala and al Qaeda.

Paul Pillar blames the continued violence in Libya on “a mélange of militias and other armed groups with a variety of interests and grievances, some of them antipathetic to the United States”:

That this has not been broadly understood is due mainly to the unrelenting effort of some in the opposition party in the United States to exploit the death of four U.S. citizens in the incident to try to discredit the Obama administration and its secretary of state at the time (who is seen as a likely contender in the next presidential election). The line propounded in this effort is, first, that the incident can have only one of two possible explanations: either the attack was a completely spontaneous and unorganized popular response to the video, or it was a terrorist attack that had nothing to do with emotions surrounding the video and instead was a premeditated operation by a particular terrorist group, Al Qaeda. The propounded line further holds that the administration offered the first of these two explanations, that this explanation was a deliberate lie, and that the second explanation is the truth.

The Times investigation demolishes all that.

He goes on to argue against the “careless application of the label Al Qaeda to a broad and variegated swath of Sunni Islamist extremism”:

This tendency misleads Americans into believing that the danger of anti-American violence in general or terrorism in particular comes from the actual Al Qaeda, the group that did 9/11, when in fact more of it comes these days from other sources—including some of those armed groups in Libya.

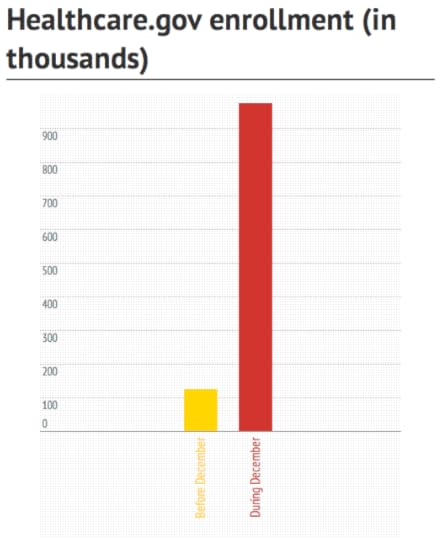

The Enrollment Surge

Kliff charts it:

Most health policy experts would expect enrollment to level off, or even fall, in January and February, when shoppers aren’t facing an imminent deadline. But they do foresee a big increase at the end of March, right before open enrollment closes. These next three months will be pretty important for seeing whether the law hits the Congressional Budget Office projection of 7 million enrollees in 2014 — or, as it has in the first three months of enrollment, continues to fall short.

What Cohn is hearing:

“What’s important now is that the systems are mostly functioning so that anyone who wants to get coverage can,” says Larry Levitt, senior vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “The outreach campaigns and advertising by insurers likely haven’t peaked yet, so I wouldn’t be at all surprised if enrollment in March is even bigger than December.”

MIT economist Jonathan Gruber, an architect of reforms, has a similarly nuanced take. “Given the technical problems at the start, and given that the important deadline is March 31, what matters right now is the trend in enrollment. In terms of overall enrollment, the trend looks quite good,” Gruber says. “What matters more is the mix in terms of the health of those enrolling, and we won’t have a clear answer on that until we see 2015 rates from insurers.”

Philip Klein wants more info on the health of enrollees:

CMS still hasn’t provided a demographic breakdown of those who have signed up for insurance through the exchange, which is a key metric for measuring the success of Obamacare, because the exchanges need a critical mass of young and healthy individuals to offset the cost of covering older and sicker enrollees and those with pre-existing conditions.

Avik Roy echoes:

What we need to know is: What is the breakdown of enrollees by age? What percentage have chronic conditions like Type 2 diabetes, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure? This is the kind of data that can help us compare the pool of enrollees in the exchanges to the normal U.S. population. It’s almost certain that, so far, this enrollment data is not encouraging. Because if it was encouraging, CMS would have released it.

Laszewski recommends looking at the exchanges yourself:

I suggest you do what the Democrats have been suggesting and visit HealthCare.gov. When you do, you will find that the entry page has a big icon on the left side, “See Plans Before I Apply.” Click on that and enter a sample age, state, county, and sample income. You don’t have to create an account or enter any personal information. You can take a look at any of the 36 federally run states. The site will show you all of the plans available, including the deductibles and co-pays with premiums that are net of subsidy. Unfortunately, most plans won’t let you checkout the provider network on the federal site.

Take a look. Put yourself in the shoes of lower middle-class and middle-class people who will likely have to pay 10% of their after tax income, net of the subsidy, for plans with an average Silver plan deductible of $2,567 and an average Bronze deductible of $4,343.

Will millions more buy Obamacare before March 31?

Combating Cancer Like AIDS

Biogeneticist Eric S. Lander makes the connection:

Therapeutic development has already been transformed by genomics. There are 800 different anticancer drugs in clinical development today. Cancer drugs used to be just cellular poisons, but almost all of these new ones are targeted at particular gene products that have been discovered. But it’s just a start. Some of the new cancer drugs can miraculously make tumors disappear. The problem is that, a year later, the cancer in many cases comes roaring back, because some of the cells have developed mutations that make them resistant. So genome scientists are now finding and targeting these mutations as well. Remember in the 1980s, when HIV was a fatal disease? What made it become a chronic, treatable disease? It was a combination of three drugs. Any one of those drugs alone, the virus could mutate its way around. But with the combination of all three, the chance that a virus could find its way around all of them was vanishingly small.

That’s what’s going to be happening in cancer. If you didn’t know the HIV story, you would be depressed: you put all this work into the drug, and a year later the cancer has developed resistance. But if you understand that this is a game of probability, and there is only a finite number of cancer cells and each has only a certain chance of mutating, and if we can put together two or three independent attacks on the cancer cell, we win.

December 29, 2013

“Mary ‘Em When They’re Fifteen”

In which the right to free speech for Phil Robertson continues. Money quote:

“Look, you wait ‘til they get to be twenty years-old and the only picking that’s going to take place is your pocket. You got to marry these girls when they’re about fifteen or sixteen and they’ll pick your ducks.”

And it appears he practiced what he now preaches. Also: could Sarah Palin please tell me what “picking your ducks” means? Her role model didn’t explain.

Quote For The Day II

“Flashback 12/29/12 …. Hard to believe this was 1 year ago today … when I reached a critical milestone of 100 days post transplant … and KJ was finally allowed to come back home. Reading this comforts me and I hope the same for you: ‘If you are depressed, you are living in the past. If you are anxious, you are living in the future. If you are at peace, you are living in the present.’

At this moment I am at peace and filled with joy and gratitude. I am grateful to God, my doctors and nurses for my restored good health. I am grateful for my sister, Sally-Ann, for being my donor and giving me the gift of life.

I am grateful for my entire family, my long time girlfriend, Amber, and friends as we prepare to celebrate a glorious new year together,” – Robin Roberts, capping one helluva gay year.

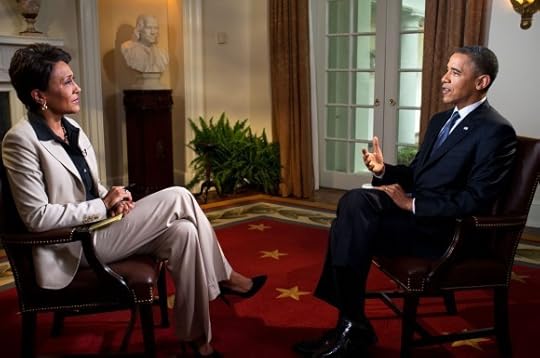

And yes, this is not news to me; and yes, it’s a huge relief that the woman to whom Obama spoke of his own “evolution” on marriage equality is no longer closeted; and yes, I ‘m glad for her survival of cancer and her own evolution as a free woman.

(Photo: U.S. President Barack Obama participates in an interview with Robin Roberts of ABC’s Good Morning America, in the Cabinet Room of the White House on May 9, 2012 in Washington, DC. During the interview, President Obama expressed his support for gay marriage, a first for a U.S. president. By Pete Souza/White House Photo via Getty Images.)

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 154 followers