Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 358

February 16, 2014

The Doctrine Of DFW

The works of David Foster Wallace inspired Joseph Winkler to return to the Talmud after falling away from Orthodoxy:

Through it all, from the religious passion to the expansive freedom of a secular life, I remained devoted to the works of Wallace. His voice—restless, wild, voracious, endlessly curious, reflective, and most important, unabashedly genuine—always made me feel less lonely, comforted in my self-doubts, and invigorated in my thoughts. He challenged readers to challenge themselves, assuming that the deepest questions belong to the province of everyone and that above all, past the religious, sexual, societal divides, we all desire deep intimacy despite the cynicism of our culture. He was also the smartest and funniest writer I ever read, and he expanded my intellectual tastes and desires. As I left the religious world, Wallace provided a sense of grounding in a world largely new to me, and his playful curiosity served as a guide through the secular culture I chose to embrace. When he hanged himself on Sept. 12, 2008, I instinctively went into shiva mode.

Wallace, in hindsight, besides his Talmudic nature, was always a rabbi to me, in a post-postmodern world where old values only meant anything if you so chose. In a new world in which I couldn’t believe in old dogma, his work still tackled morality, the nature of belief, obligations, responsibility, and the human spirit.

In an essay claiming Wallace was some manner of conservative, James Santel plumbs related themes:

What strikes me as absent from Wallace’s essays isn’t sincerity or even necessarily optimism; what’s missing is faith.

Wallace was narrowly correct in saying that we’re all marooned in our own skulls, and that we ultimately have to make up our own minds about things. But most of us draw a line where Wallace couldn’t in his interview, just before “true empathy’s impossible.” If by “true empathy” Wallace means total inhabitance of another’s inner workings, then yes, true empathy is impossible. But most of us don’t go there. In order to get along in life, we put our faith in the good will of people we love, or in higher beings, or in the rule of law, or in inspiring public figures like John McCain and Barack Obama. Some of us even put our faith in literature.

This is the real tragedy of Wallace’s conservatism. It entailed a curious blindness to the extent to which his writing, imbued as it was with the rare ability to dissect contemporary problems with humanity and humor, reached people, inspiring in his readers a rare devotion born of the sense that Wallace was speaking directly to them. (If you need evidence of this, look at the memorial to Wallace on the McSweeney’s website.) And yet Wallace, widely regarded as the premier literary talent of his generation, ultimately had little faith in his chosen medium. Heavily influenced by Wittgenstein, he saw language as at best the faded messages we seal into bottles and toss into uncertain waters from our little desert island, hoping they reach someone else’s. Wallace (“It goes without saying that this is just one person’s opinion”) could never totally buy into this project. “It might just be that easy,” he told his interviewer in 1993. But for Wallace, blessed and cursed with that endlessly perceptive mind, it was never that easy.

Previous Dish on DFW here, here, and here.

Mental Health Break

No Free Will, No Law And Order?

In a long review of Sam Harris’s Free Will, Daniel Dennett squirms at the practical, political consequences of full-throated determinism:

Harris, like the other scientists who have recently mounted a campaign to convince the world that free will is an illusion, has a laudable motive: to launder the ancient stain of Sin and Guilt out of our culture, and abolish the cruel and all too usual punishments that we zestfully mete out to the Guilty. As they point out, our zealous search for “justice” is often little more than our instinctual yearning for retaliation dressed up to look respectable. The result, especially in the United States, is a barbaric system of imprisonment—to say nothing of capital punishment—that should make all citizens ashamed. By all means, let’s join hands and reform the legal system, reduce its excesses and restore a measure of dignity—and freedom!—to those whom the state must punish. But the idea that all punishment is, in the end, unjustifiable and should be abolished because nobody is ever really responsible, because nobody has “real” free will is not only not supported by science or philosophical argument; it is blind to the chilling lessons of the not so distant past. Do we want to medicalize all violators of the laws, giving them indefinitely large amounts of involuntary “therapy” in “asylums” (the poor dears, they aren’t responsible, but for the good of the society we have to institutionalize them)? I hope not.

Harris shrugs off the complaint:

These concerns, while not irrational, have nothing to do with the philosophical or scientific merits of the case. They also arise out of a failure to understand the practical consequences of my view. I am no more inclined to release dangerous criminals back onto our streets than you are.

In my book, I argue that an honest look at the causal underpinnings of human behavior, as well as at one’s own moment-to-moment experience, reveals free will to be an illusion. (I would say the same about the conventional sense of “self,” but that requires more discussion, and it is the topic of my next book.) I also claim that this fact has consequences—good ones, for the most part—and that is another reason it is worth exploring. But I have not argued for my position primarily out of concern for the consequences of accepting it. And I believe you have.

A Poem For Sunday

“At the Beach” by Elizabeth Alexander:

Looking at the photograph is somehow not

unbearable: My friends, two dead, one low

on T-cells, his white T-shirt an X-ray

screen for the virus, which I imagine

as a single, swimming paisley, a sardine

with serrated fins and a neon spine.

I’m on a train, thinking about my friends

and watching two women talk in sign language.

I feel the energy and heft their talk

generates, the weight of their words in the air

the same heft as your presence in this picture,

boys, the volume of late summer air at the beach.

Did you tea-dance that day? Write poems

in the sunlight? Vamp with strangers? There is

sun under your skin like the gold Sula

found beneath Ajax’s black. I calibrate

the weight of your beautiful bones, the weight

of your elbow, Melvin,

on Darrell’s brown shoulder.

(From Crave Radiance: New and Selected Poems © 2010 by Elizabeth Alexander. Reprinted with kind permission of Graywolf Press. Photo of Fire Island in the autumn by Harvey Barrison)

The Butt Song From Hell

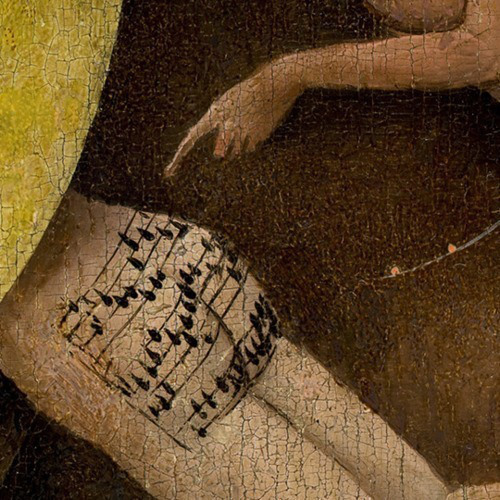

Ever notice this guy in Hieronymous Bosch’s “Garden of Earthly Delights”? An Oklahoma college student transcribed the score printed on his ass and made a recording of it:

So what does a 500-year-old “butt song from Hell” actually sound like? To my ears something like the creepy orgy scene soundtrack from Eyes Wide Shut—which, given the painting’s content, is oddly appropriate. But make up your own mind by listening here.

A choral arrangement has already dropped.

Seeking Absolution In The Recovery Room

While conducting ethnographic research in an abortion clinic in the early 2000s, Lori Freedman was struck by how many of the patients, mostly Latina women, turned to their nurses for spiritual comfort and forgiveness:

Beatriz and Claudia starkly challenged my own unexamined assumptions that religion and abortion mixed like oil and water. I marveled at their easy confidence that they could help these women spiritually. There is no script for such moments, certainly no mainstream religious scripts that so readily grant women who get abortions forgiveness in such reassuring ways. In fact, data show that women who get abortions are likely to keep it a secret precisely because they fear they will receive harsh disapproval. They fear they will be judged and that the people that they care about will see them as less than what they were.

Ironically, for these patients, the abortion clinic may be one of the few safe spaces to seek spiritual counsel.

Face Of The Day

Bear Kirkpatrick shares how playing with hair coverings inspired him to create his series “Wallportraits”:

The first Wallportrait came about because I had my friend Ashley in my studio and I was playing dress up with her. I had borrowed clothes from a vintage store and from a costume maker and was just dressing her this way and that and taking photos, just seeing what happens. Playing. Most photographers hire Ashley because of her incredible hair, but in my mindless playing I wondered what she might look like without that hair. You know, take away the obvious, the given. I didn’t “think” this. I just wrapped her head with apiece of white fabric and took some pictures.

And her eyes! Man, they were out of this world! I mean, something really shifted visually — my own visual response system seemed to completely change its footing and include information that was newly revealed. Not by addition but by subtraction. And so there’s a clear antecedent there to my own experience of having been deaf when I was a child. Something taken away that can lead to discovery.

(Photo by Bear Kirkpatrick)

The Basis Of God

Adam Gopnik ponders shifting cultural attitudes toward atheism and belief:

[T]he need for God never vanishes. Mel Brooks’s 2000 Year Old Man, asked to explain the origin of God, admits that early humans first adored “a guy in our village named Phil, and for a time we worshipped him.” Phil “was big, and mean, and he could break you in two with his bare hands!” One day, a thunderstorm came up, and a lightning bolt hit Phil. “We gathered around and saw that he was dead. Then we said to one another, ‘There’s something bigger than Phil!’ ” The basic urge to recognize something bigger than Phil still gives theistic theories an audience, even as their explanations of the lightning-maker turn ever gappier and gassier. …

As the explanations get more desperately minute, the apologies get ever vaster. David Bentley Hart’s recent “The Experience of God: Being, Consciousness, Bliss” (Yale) doesn’t even attempt to make God the unmoved mover, the Big Banger who got the party started; instead, it roots the proof of his existence in the existence of the universe itself. Since you can explain the universe only by means of some other bit of the universe, why is there a universe (or many of them)? The answer to this unanswerable question is God. He stands outside everything, “the infinite to which nothing can add and from which nothing can subtract,” the ultimate ground of being. This notion, maximalist in conception, is minimalist in effect. Something that much bigger than Phil is so remote from Phil’s problems that he might as well not be there for Phil at all. This God is obviously not the God who makes rules about frying bacon or puts harps in the hands of angels. A God who communicates with no one and causes nothing seems a surprisingly trivial acquisition for cosmology—the dinner guest legendary for his wit who spends the meal mumbling with his mouth full.

Dreher protests:

I can only assume, in charity, that Gopnik read Hart’s book too quickly, because this is a significant distortion of the theologian’s arguments. Hart is not arguing for a specific idea of God; he is rather making a more general argument. He is attempting to establish why there is Something rather than Nothing, and to show that atheist claims are actually less reasonable than monotheistic claims. Hart returns to classical metaphysics to make his argument. … It is very, very far from the case that Hart argues for “a God who communicates with no one and causes nothing,” and it is actually shocking that Gopnik alleges this. True, Hart is talking in abstractions, but these abstractions are necessary to establish the metaphysical basis for his claims.

Douthat challenges (NYT) Gopnik’s assessment of people who have replaced “the old-time religion with a more abstract, post-personal God”:

Of course there are believers whose conception of divinity is functionally deistic, liberal religious intellectuals for whom apophatic faith substitutes for revelation rather than enriching it, and probably Gopnik’s social circle includes more examples of this type than it does of Hart’s more traditional sort. But make a list of prominent Christian scholars and philosophers and theologians (to say nothing of apologists and popularizers … artists and novelists … or, God help us, journalists), and you’ll find that plenty of the names — from Charles Taylor to Alvin Plantinga, Alasdair McIntyre to N.T. Wright, Rowan Williams to Joseph Ratzinger — do actually believe in all that Nicene Creed business, believe that the God of philosophy can still care about Phil and Ross and Adam, and share Hart’s view that religion can be intellectually rigorous without making prayer empty and miracles impossible.

In an interview, Gary Cutting and Alvin Plantinga further explore (NYT) the issue:

G.G.: … [I]sn’t the theist on thin ice in suggesting the need for God as an explanation of the universe? There’s always the possibility that we’ll find a scientific account that explains what we claimed only God could explain. After all, that’s what happened when Darwin developed his theory of evolution. In fact, isn’t a major support for atheism the very fact that we no longer need God to explain the world?

A.P.: Some atheists seem to think that a sufficient reason for atheism is the fact (as they say) that we no longer need God to explain natural phenomena — lightning and thunder for example. We now have science.

As a justification of atheism, this is pretty lame. We no longer need the moon to explain or account for lunacy; it hardly follows that belief in the nonexistence of the moon (a-moonism?) is justified. A-moonism on this ground would be sensible only if the sole ground for belief in the existence of the moon was its explanatory power with respect to lunacy. (And even so, the justified attitude would be agnosticism with respect to the moon, not a-moonism.) The same thing goes with belief in God: Atheism on this sort of basis would be justified only if the explanatory power of theism were the only reason for belief in God. And even then, agnosticism would be the justified attitude, not atheism.

Previous Dish on faith and Hart’s book here and here.

Pastafarian Pin-Ups

The South Bank University Atheist Society in the UK recently stirred controversy with a poster that replaced the image of God in Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam with the flying spaghetti monster. The poster was banned for being “religiously offensive,” a charge Jonathan Jones finds preposterous:

The artist has not done anything to God. All that has been altered here is a painting by Michelangelo. OK, for some of us Michelangelo is as godlike as artists get – but that does not make his images sacred. … The first person to parody Michelangelo’s portrait of God was Michelangelo himself. While he was working in the Sistine chapel, standing … on a wooden platform suspended just under the ceiling, he wrote a poem lamenting his lot. He complains about the paint dripping down on his upturned face and beard, about having to twist his body monstrously as he reaches up all day and night. By the manuscript poem, he added a cartoon. A naked artist stretches up to paint God on the ceiling – but God is a crude graffito, an absurd caricature with long spiky hair. Not a million miles from the Spaghetti Monster, in fact.

In other words, Michelangelo did not think there was anything inherently sacred about his image: it was a picture of God made by a man; it was not a holy relic. Later in his life, he was attacked for this. Michelangelo, complained pious critics, put art before God.

On Wednesday, the student union at London South Bank University issued a statement apologizing for the censorship:

We have apologised to the Atheist Society for the actions taken and the distress that it has caused. From a Union perspective the ‘Flying Spaghetti Monster’ Poster has not been banned and we have agreed with the Atheist Society to reprint these posters and distribute them on campus for them. They will also be displayed inside the Union’s locked poster boards in order to prevent them being taken down by other students. … We remind students that the appropriate response to opinions they may find offensive is to engage in healthy debate respecting the rights of others to hold views or beliefs differing from their own.

Terry Firma is relieved by the apology, but Tom Bailey sees the poster ban as part of a broader trend:

While bans and acts of censorship on the grounds of religious offence are not justified, they are based on the idea that if something is offensive – actually or potentially – to certain segments of the student population, then it can rightfully be banned. Bans, whether on the basis of religion or sexism, are based on intolerance, an intolerance of certain things that some people may find objectionable, distasteful, uncouth or offensive, and which in turn compels them to be censored – whether it is Robin Thicke’s lewd lyrics or Photoshopped frescos.

Yet the faith-bashing warriors who raged against the censoring of t-shirts at the [London School of Economics] and the censoring of a poster at South Bank University will, for the most part, have little to say about the wider culture of bans and censorship at universities. The banning of the spaghetti-monster poster at South Bank is not a creeping resurgence of intolerant religion or a capitulation to Christian complainers by university officials. Rather, it is part of an increasingly intolerant climate at universities in which offence, religion-based or otherwise, is deemed a legitimate ground for something to be banned.

Previous Dish on the flying spaghetti monster here, here, and here.

(Image of offending poster via Facebook)

February 15, 2014

Who Says Bigger Is Better?

Research reveals a link between straight men’s socioeconomic status and the breast size they prefer for their partners:

[T]he present results indicate that men in relatively low socioeconomic sites rate larger breast sizes as more physically attractive than do their counterparts in moderate socioeconomic sites, who in turn rate a larger breast size as more attractive than individuals in a high socioeconomic site. In broad terms, these results are consistent with previous studies showing that there is an inverse relationship between socioeconomic status and breast and body size judgements. These results provide preliminary evidence that breast size may act as an indicator of calorific storage and that men in environments characterised by relative resource insecurity perceive larger breast sizes as more attractive than their counterparts in higher socioeconomic contexts.

Researchers also evaluated how hunger affected judgment:

[H]ungry men rated a significantly larger female breast size as physically attractive than did satiated men. Although the effect size of this difference was small-to-moderate, it nevertheless suggests that there are significant differences in the attractiveness ratings based on breast size between hungry and satiated men. In addition, the results of this study corroborate previous work showing that hungry men rate a significantly heavier female body size as attractive …. Moreover, these results are in line with the findings of Study 1: in both studies, it appears to be the case that men who experience relative resource insecurity show a preference for a larger breast size than do men who experience resource security.

(Hat tip: Hazlitt)

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 153 followers