Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 335

March 12, 2014

The Cat That Conquered The West

Noah Sudarsky describes the mountain lion as “something of a wildlife success story”:

It is the most widespread large carnivore in the Americas, managing to survive even as other predators have nearly perished. The wolf was hunted to the brink of extinction, and has been able to make a shaky comeback thanks only to expensive and difficult reintroduction programs. The grizzly, once found on the shores of San Francisco Bay, remains only in the Northern Rockies and Alaska, ecosystems large enough to accommodate its need for large, open spaces. The coyote, famously, is one predator that has seen an actual gain in numbers since European colonization (thanks mostly to the disappearance of other carnivores). But the coyote’s success – like that of, say, the crow and the raccoon – is due in large part to the animal’s ability to accommodate itself to human development. In contrast, the cougar remains as cagey as ever.

Cougars are, above all, solitary, connecting with other cougars only to mate. Since it is effectively invisible, this enigmatic species doesn’t enjoy (or suffer) the kind of cult of personality that surrounds the grizzly and the wolf. A cougar sticks to the shadows, and that instinct helps explain its enduring success, a success that seems all the more remarkable given the odds stacked against it. And the odds are staggering.

The Coveillance State

Kevin Kelly believes that, rather than try to resist surveillance, we should make it work for us:

We’re expanding the data sphere to sci-fi levels and there’s no stopping it. Too many of the benefits we covet derive from it. So our central choice now is whether this surveillance is a secret, one-way panopticon — or a mutual, transparent kind of “coveillance” that involves watching the watchers. The first option is hell, the second redeemable. …

The remedy for over-secrecy is to think in terms of coveillance, so that we make tracking and monitoring as symmetrical — and transparent — as possible.

That way the monitoring can be regulated, mistakes appealed and corrected, specific boundaries set and enforced. A massively surveilled world is not a world I would design (or even desire), but massive surveillance is coming either way because that is the bias of digital technology and we might as well surveil well and civilly. In this version of surveillance — a transparent coveillance where everyone sees each other — a sense of entitlement can emerge: Every person has a human right to access, and benefit from, the data about themselves. The commercial giants running the networks have to spread the economic benefits of tracing people’s behavior to the people themselves, simply to keep going. They will pay you to track yourself. Citizens film the cops, while the cops film the citizens. The business of monitoring (including those who monitor other monitors) will be a big business. The flow of money, too, is made more visible even as it gets more complex.

Michael Brendan Dougherty pushes back:

Kelly’s vision of the future is more straightforwardly dystopian than any of the other controversial visions of a libertarian “opt-out” society emanating from Silicon Valley. He believes human life can, and ought to be, reduced to data points, that people will consent to be ruled like a mere cell in an Excel Spreadsheet and will even begin to understand themselves in the rudimentary categories of computation.

His essay is an occasion to remind ourselves that the future doesn’t unfurl out of present trends extrapolated into infinity; it is contested. And we have older, rather durable technologies that can prevent us from being dropped into a digitized fishbowl: the art of political resistance for one. Our Constitution, another.

The Enduring Appeal Of Ruins

In a review of the Tate Britain’s current show Ruin Lust, Frances Stonor Saunders suggests that urban wrecks offer a shortcut to self-transcendence, “a steroidal sublime that enables us to enlarge the past since we cannot enlarge the present”:

When ruin-meister Giovanni Piranesi introduced human figures into his “Views of Rome,” they were always disproportionately small in relation to his colossal (and colossally inaccurate) wrecks of empire. It’s not that Piranesi, an architect, couldn’t do the math: he wasn’t trying to document the remains so much as translate them into a grand melancholic view. As Marguerite Yourcenar put it, Piranesi was not only the interpreter but “virtually the inventor of Rome’s tragic beauty.” His “sublime dreams,” Horace Walpole said, had conjured “visions of Rome beyond what it boasted even in the meridian of its splendor.”

Piranesi’s engravings were such a potent framing device for the cultural imagination of the 18th century that the actual ruins had to compete with them. Many Goethes and Gibbons arrived in Rome with these images imprinted on their minds, and when this superimposition cleared, the real thing was initially something of a disappointment. François-René de Chateaubriand’s account of a visit to the Colosseum in July 1803 conformed to all the requirements of the ruin gaze: “The setting sun poured floods of gold through all the galleries … nothing was now heard but the barking of dogs”; a distant palm tree, glimpsed through an arch, “seemed to have been placed in the midst of this wreck expressly for painters and poets.” But when he returned to this locus romanticus a few months later, he saw nothing but a “pile of dreary and misshapen ruins.”

Previous Dish on ruins here, here, and here.

(Piranesi’s Veduta dell’ arco di Costantino, e dell’ anfiteatro Flavio detto il colosseo, 1760, via Leiden University.)

Rethinking Cohabitation

Jessica Grose flags a new study debunking the conventional wisdom that shacking up before marriage leads to divorce:

According to a paper [sociologist Arielle] Kuperberg is publishing in the April issue of the Journal of Marriage and Family, it’s not premarital cohabitation that predicts divorce. It’s age.

It’s long been known that there’s a correlation between age at first marriage and divorce—the younger you get married the first time, up until your mid-20s, the more likely your marriage is to break up. Kuperberg looked at data from the National Survey of Family Growth from 1996–2010 and found that the same goes for cohabitators. If you move in together in your teens or early 20s, then you are more at risk for divorce; the reason that couples who move in together young break up “is the same reason age of marriage is a predictor of divorce: people aren’t prepared for those roles,” Kuperberg says.

Another study discovered “that the length of time a couple has been romantically involved before moving in together is also crucial to whether they end up divorcing”:

Those with higher education levels tend to take longer to move in with their partners, she found. Half of college-educated women moved in with their partners after at least a year; one-third were romantically involved for two years before joining house. Data from the most recent National Survey of Family Growth show that more than half of women with only a high school degree in a cohabitating relationship moved in with their partner in less than six months.

Professor [Sharon] Sassler found in her research that many couples with lower incomes and less education decided to move in together because of financial pressures. She argues that it is the type of premarital cohabitation that predicts divorce, not necessarily cohabitation in itself.

March 11, 2014

The Best Of The Dish Today

First, a little house-keeping. Ross Douthat has an excellent post on the question of religious liberty and gay rights. It’s a judicious argument that cultural isolation can led to infringement of religious liberty, given how complex our society is. Ross asks my help in defending the religious from the potential abuses of the pro-gay majority. He’s got it. But so far, as he concedes, it’s not a huge problem. And excessive self-pity is pathetic.

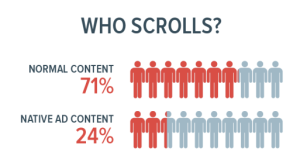

On another of my obsessions, there’s a great piece in Time from the CEO of Chartbeart, Tony Haile. It was best summed up by a re/code post linking to it: “No One’s Looking At Your Native Ads Either.” It’s a fascinating look at click-bait culture online, and the increasing frenzy  for pageviews, as well as the surrender to the public relations industry. And it contains some seriously good news, best summed up in a simple chart (on the right).

for pageviews, as well as the surrender to the public relations industry. And it contains some seriously good news, best summed up in a simple chart (on the right).

Readers soon figure out that the lame p.r. piece by some dude from Dell is indeed a lame p.r. piece from some dude at Dell, and they stop reading far more quickly than they do when an actual journalist is writing, you know, an actual piece. So that means readers are sussing out the scam pretty quickly. What happens next to a website that keeps subjecting its readers to the same grift? A declining readership and a declining respect from its readership. After that, the corporations pull the native ads – especially if they see the metrics above. Haile:

The truth is that while the emperor that is native advertising might not be naked, he’s almost certainly only wearing a thong. On a typical article two-thirds of people exhibit more than 15 seconds of engagement, on native ad content that plummets to around one-third.

Today, I remembered Joe McGinniss, hero of the Palin wars, and spelled out the truly remarkable accusation of criminality that Senator Feinstein unloaded on the CIA this morning. We gawked at strangers being filmed kissing each other, and at the anti-Barbie. And, in order to speed my sojourn in Purgatory, I went another round with Rod Dreher on religious liberty.

The most popular post of the day was last night’s Best Of The Dish on Obama’s impressive economic record, followed by The Christianist Closet?

See you in the morning.

(Photo: Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) returns to her Senate office after speaking on the floor of the Senate where she accused the CIA of breaking federal law by secretly removing sensitive documents from computers used by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, the committee tasked with congressional oversight of the CIA. Feinstein said, ‘I am not taking it lightly.’ By Win McNamee/Getty Images.)

Ohm Online

Sue Thomas, author of Technobiophilia: Nature and Cyberspace, looks at how spiritual seekers are using apps and social media to enhance their meditation sessions. Consider Insight Timer, an app that offers guided meditations and connects users in real time across the globe:

So how does it feel to meditate alongside invisible people? Well if, like me, you’ve spent a lot of time in virtual worlds, gaming online, or even just chatting in Facebook, you’ll know that there can often be a strong sense of co-presence. During research for my book on technobiophilia, our love of nature in cyberspace, I found that as early as 1995 the Californian magazine Shambhala Sun described the internet as an esoteric place for meditation which provided “a feeling of complete and total immersion, in which the individual’s observer-self has thoroughly and effortlessly integrated.” I have felt that “experience of the moment” many times while using Insight Timer to spend time “on the cushion” alongside others in virtual space.

Previous Dish on technobiophilia here.

Leaving Our Iraqi Allies Behind

Neve Gordon, reviewing a pair of books that shine light on the “very dark sides of occupation” in Iraq, considers the role of Iraqis who collaborated with the US military. He assesses To be a Friend Is Fatal, a nonfiction account by Kirk Johnson, who worked with USAID in Baghdad and Fallujah and “founded the List Project to Resettle Iraqi Allies and raised money, wrote op-eds, mobilized journalists, and lobbied Congress to find a solution for these Iraqi refugees”:

Johnson’s book ends up being a poignant story about bureaucratic red tape and lies, where the US government constantly made promises to address the plight of the collaborators while simultaneously creating insurmountable obstacles for their visa applications. Samantha Power and her friends were unwilling to say it, but they preferred to leave behind a hundred innocent Iraqi employees facing possible assassination than to admit one former collaborator who could potentially cause damage — nobody, Johnson surmises, wanted his or her signature to be on the visa papers of the next 9/11 hijacker.

This is the major difference between Johnson’s List Project and Operation Baghdad Pups, an initiative to resettle Iraqi dogs that had befriended US troops. “No Buddy Gets Left Behind!” reads the organization’s flashy website banner followed by the imperative: “Abandoning Charlie in the war-ravaged country would have meant certain death for him.” In exchange for a $1,000 donation, the group promises to cut through the US government’s red tape in order to bring these pets to “freedom.” In July 2012, CNN reported that Americans had donated $27 million to help Iraqi dogs (nearly 14 times the amount the List Project was able to raise over the years). On January 2, 2013, President Obama signed the 2013 National Defense Authorization Act, which included an amendment to grant dogs working for the US military the status of “Canine Members of the Armed Forces.”

While I don’t have anything against the resettlement of dogs, witnessing the government’s radically different approach toward those Iraqis who came to the US’s aid leaves, to use a British understatement, a foul taste in one’s mouth.

Quote For The Day

“I do not remember Piers Morgan saying he had hacked my phone … He may have said it, I just can’t remember it,” – Rebekah Brooks, on trial today.

Ephemeral Employment

Michael Grabell investigates the struggles of our 2.8 million-strong temporary workforce:

Overall, nearly one-sixth of the total job growth since the recession ended has been in the temp sector. Many temps work for months or years packing and assembling products for some of the world’s largest companies, including Walmart, Amazon and Nestlé. They make our frozen pizzas, cut our vegetables and sort the recycling from our trash. They unload clothing and toys made overseas and pack them to fill our store shelves.

The temp system insulates companies from workers’ compensation claims, unemployment taxes, union drives and the duty to ensure that their workers are citizens or legal immigrants. In turn, temp workers suffer high injury rates, wait unpaid for work to begin and face fees that depress their pay below minimum wage. Temp agencies consistently rank among the worst large industries for the rate of wage and hour violations, according to a ProPublica analysis of federal enforcement data.

Another report sheds light on the squalid living conditions of California’s farmworkers:

Don Villarejo, the longtime farmworker advocate who authored the report, tells In These Times that growers have “systematically” reduced investment in farmworker housing over the past 25 years in order to reduce overhead costs and to avoid the trouble of meeting state and federal regulations, which were established as part of a broader overhaul of agricultural labor, health and safety standards during the 1960s and 1980s. According to Villarejo, workers’ modern material circumstances are little improved from the old days of the Bracero system. That initiative—the precursor to our modern-day guestworker migrant program—became notorious for shunting laborers into spartan cabins, tents and other inhospitable dwellings on the farms themselves, beset with entrenched poverty and unhealthy, brutish conditions.

Even today, however, surveys and field reports have revealed that a large portion of workers are squeezed into essentially unlivable spaces. Some dilapidated apartments and trailer parks lack plumbing or kitchen facilities, much less any modicum of privacy; others are exposed to toxic pesticide contamination or fetid waste dumps. Workers can “live in a single-family dwelling with perhaps a dozen to 20 [people] crowding in,” Villarejo says.

March 10, 2014

Has The Web Made Us Freer?

Perhaps we’re beginning to answer this question with some data for the first time. Linda Besner wonders if the promise of an Internet as a great cultural leveler – granting an audience to obscure artists as well as to the well-known and well-funded – might be wildly overstated:

In The People’s Platform, [author Astra] Taylor discusses how the supposedly open, free, and hierarchy-busting world wide web has failed to do better than a roomful of public television commissioners in encouraging the production or consumption of risky independent cultural products. In fact, it does significantly worse. Internet traffic follows a statistical pattern known as power law distribution; essentially, while there is a wide range of available options, almost everyone is crowded together at the most popular end of the spectrum. It’s a problem that’s getting worse: “In 2001, ten Web sites accounted for 31 per cent of U.S. page views,” Taylor writes, “by 2010, that number had skyrocketed to 75 percent.” Most nights, 40 per cent of the U.S.’s bandwidth is taken up by people watching Netflix movies.

In a similar vein, Dougald Hine challenges notions of the Internet as an agent of “liberation from the boredom of industrial society, a psychedelic jet-spray of information into every otherwise tedious corner of our lives”:

At best, it allows us to distract ourselves with the potentially endless deferral of clicking from one link to another. Yet sooner or later we wash up downstream in some far corner of the web, wondering where the time went. The experience of being carried on these currents is quite different to the patient, unpredictable process that leads towards meaning.

The latter requires, among other things, space for reflection – allowing what we have already absorbed to settle, waiting to see what patterns emerge. Find the corners of our lives in which we can unplug, the days on which it is possible to refuse the urgency of the inbox, the activities that will not be rushed. Switch off the infinity machine, not forever, nor because there is anything bad about it, but out of recognition of our own finitude: there is only so much information any of us can bear, and we cannot go fishing in the stream if we are drowning in it.

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 153 followers