Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 130

October 12, 2014

Mental Health Break

No Conservative Caricature

In a review of Robert Howse’s Leo Strauss: Man of Peace, Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft remarks on how the author “defends Strauss against his caricature as a ‘cult figure of the right'”:

Howse’s “man of peace” discussion involves two central, intertwined claims: first, that Strauss was not a foe of liberalism, constitutionalism, or democracy, as he is commonly taken to be. Howse’s Strauss looks beyond the limiting polarization of liberalism and anti-liberalism, is willing to support constitutional democracy (just as the historical Strauss was, of course, happy to live within the constitutional democracy of the United States), and asks how philosophers might contribute to constitutional thought. …

Howse’s other claim is biographical: he argues that we should see Strauss’s development in terms of t’shuvah (Hebrew for “repentance”) performed for the youthful sin of illiberal and nihilistic thinking: he calls this “Strauss’s self-overcoming of anti-liberalism,” a form of surrogate repentance not through religious piety but by philosophical means. Strauss came to recognize, Howse argues, that his early attraction to the thought of Schmitt and Heidegger had been a youthful error, and all his subsequent projects must be understood as a slow arc of reorientation. Strauss’s persistent contemplation of non-liberal positions throughout his career — up to and including his study of Machiavelli, of which Howse is a very sensitive reader — was never an endorsement of those positions. It was driven by a need to tarry with the negative, to take critical distance from it, and then assume more moderate political and philosophical stances. For Howse’s Strauss, pre-modern political thought was not a source of authority but rather of “critical distance toward the present.”

Of Whiskers And Worship

Kimberly Winston analyzes Christianity’s “on-again, off-again relationship with the beard”:

St. Augustine wrote: “The beard signifies the courageous; the beard distinguishes the grown men, the earnest, the active, the vigorous.” But around 1000 A.D., the Canons of Edgar forbade clerical beards, declaring “Let no man in holy orders conceal his tonsure, nor let himself be misshaven nor keep his beard for any time, if he will have God’s blessing and St. Peter’s and ours.” And as for cleanliness (of face) being next to godliness, the Franciscans equate the beard with manliness. “The Friars shall wear the beard, after the example of Christ most holy,” their constitution reads, “since it is something manly, natural, severe, despised and austere.”

Ditto for the Eastern Orthodox, where a clergyman’s beard is seen as a sign of his devotion to God.

Orthodox Christians frequently cite Numbers 6:5 for their beards: “a razor shall not come upon his head, until the days be fulfilled which he vowed to the Lord: he shall be holy, cherishing the long hair of the head all the days of his vow to the Lord.” Today, beards are super popular among Christian hipsters. Exhibit A:Bearded Gospel Men, a blog for Christian men with big beards. Last year, Christianity Today published a handy-dandy guide to parsing a Christian man’s theology, denomination and profession by the cut of his beard.

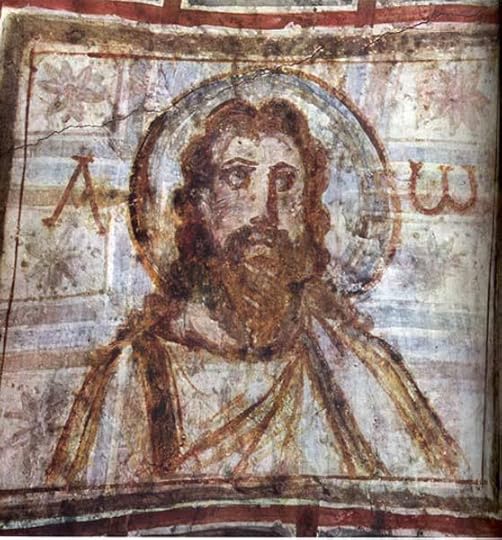

(Photo: This fourth-century mural painting from Rome’s catacombs of Commodilla is one of earliest known images of a bearded Christ. Earlier Christian art in Rome portrayed Jesus as the Good Shepherd disguised as Orpheus: young, beardless, and in a short tunic. During the fourth century, Jesus started to be depicted as a man of identifiably Jewish appearance, with a full beard and long hair, a style not usually worn by Romans. Via Wikimedia Commons.)

Robinson’s Revelatory Prose

Like previous critics, Michelle Orange emphasizes the role of grace in Marilynne Robinson’s new novel, Lila:

Robinson’s genius is for making indistinguishable the highest ends of faith and fiction, evoking in her characters and her readers the paradox by which an individual, enlarged by the grace of God, or art, acquires selfhood in acquiring a sense of the world beyond the self—the sublime apprehension that other people exist.

Which is to say that Robinson’s animating theme—grace—is also central to her genius. Described as “a sort of ecstatic fire that takes things down to essentials,” grace is evidenced in both the particular and the abstract: as laughter, a beloved face or voice, or as “playing catch in a hot street . . . leaping after a high throw and that wonderful collaboration of the whole body with itself”; but also in forgetting “all the tedious particulars,” in feeling the presence of a “mortal and immortal being.” “A character is really the sense of a character,” Robinson has written, and hers suggest, above the particulars, how the mysteries of grace persist in human beings, those wanting creatures who move Ames with their incandescence, the presence “shaped around ‘I’ like a flame on a wick, emanating itself in grief and guilt and joy and whatever else.”

Wyatt Mason focuses on how Robinson’s characters approach self-understanding:

She documents how Lila’s mind changes, not owing to the efforts of some external force but out of a righteous need of her own: to understand her husband, to speak his language, to forge a language of her own that will be spoken with, to, and for him and for them.

One of the book’s most telling passages involves watching Lila’s mind as she sits in her house, pregnant, reading the Book of Job, registering the lines and considering them. The act of reading the Bible as high drama may seem unlikely, but through it, Robinson has managed to portray how a mind with no religiosity might meet a book Robinson loves fiercely and, in its pages, find a road to a self that learns a new language: her own language. As it turns out, there is extraordinary drama in the story of how we learn to speak to ourselves.

In a recent interview, Robinson addressed this connection between faith and language:

As you write, do you draw on language found in your faith? What are the strengths of religious language, or what are the limitations of language when it comes to talking about faith and belief?

Language is limited in its nature. It’s like consciousness itself. It’s defective, and you can push at it. You can make it do things you wouldn’t have known it can do. One of the things that is a benefit to me is that, because I have been interested in a particular theology, it makes a coherent language. It’s internally self-referential, in a way. This could be true of anyone who is deeply acquainted with any tradition. This particular tradition was very verbal, so you have a very rich literature that pushes the articulation of certain basic ideas.

We have anxiety about differences. We are different, anyway, so we might as well calm down about it. But one of the things that we have to do is understand that within the system that is anyone’s difference is incredibly enabling. It means people before me have pondered the response to death. People before me have pondered the reality of time in different dialects. This is beautiful. This is not a thing to be anxious about. For my own Calvinistic purposes, I would like to see the tradition that I speak from re-animated, fleshed out. It’s human, it’s experience. Only religion fully realizes the arc of human life, and so much beautiful thought has gone into this over our eons of time.

October 11, 2014

Face Of The Day

For his series Burlesque, Sean Scheidt photographed performers before and after their transformations:

In his portraits, Scheidt captures the virtually nondescript everyday face of the performers. These are people who, aside from the occasional colored hair, look, well… normal. In Scheidt’s description of the work, he says that they tended to be quite reserved at first, which made the transformation into their characters all the more transfixing.

Scheidt described his inspiration in an interview earlier this year:

It was really a confluence of two separate things. First, I was hired to do a shoot for DNA theater. This allowed me to go backstage and get a glimpse of the transformation of the actors. About this time, I was also reading Harpo Marx’s autobiography. Marx talked a lot about Judy Garland, which sent me to search her out on YouTube. I was amazed to see how, even in her declining years, Garland lit up, once she stepped onto the stage. I guess it was then that I realized the stage has the power to transform a person into someone else. The question I wanted to explore was finding the reality within that transformation.

He added:

Capturing those moments, I believe, helps to humanize these performers. If you were just seeing the “after” shots alone, you might make certain pre-conceived judgements about the person behind the make-up. I hope this series gets people to think about their reactions to these men and women.

See more of his work here and here.

Sex For Commies

Colin Marshall unearths Do Communists Have Better Sex?, a 2006 documentary (NSFW) that suggests East Germans did, indeed, best their West German counterparts in bed:

The documentary proposes that, for all its deficiencies, the German Democratic Republic actually put forth a remarkably progressive set of policies related to such things as birth control, divorce, abortion, and sex education — a precedent to which some non-communist countries still haven’t caught up. However forward-thinking you might find all this, it did have trouble meshing with other communist policies: the state’s rule of only issuing housing to families, for instance, meant that women would get pregnant by about age twenty in any case. We must admit that, ultimately, citizens of the showcase East Germany had a better time of it than did the citizens of Soviet Socialist Republics farther east. And if the Ossies had a better Cold War between the sheets than did the Wessies, well, maybe they just did it to escape their country’s pervasive atmosphere of “unerotic dreariness.”

A Hard Sell?

A new Viagra ad, which features a woman breathily imploring viewers to talk to their doctors about the drug, prompts Ian Crouch to consider a history of advertising for E.D. drugs:

[A]lthough the ad is essentially a come-on by a beautiful woman, it is refreshingly frank about sex, which means that it is markedly better than past ads that relied on silly or crass innuendo: Levitra’s football-through-the-tire-swing ad; Viagra’s “We Are the Champions” mass male celebration; Cialis’sadjacent his-and-her bathtubs. The rare exception is the first television commercial Viagra ever ran, which turns out also to have been the brand’s best, featuring the former Senator and Republican Presidential candidate Bob Dole. That ad, which looks rather oddly like a campaign spot, became a punch line, mocked later by even Dole himself. But, watching it now, it seems far more forthright, honest, and even dignified than the ads that followed. Dole makes note of the ways in which the subject might make viewers uncomfortable, but he tells the audience, basically, to grow up: “You know, it’s a little embarrassing to talk about E.D., but it’s so important to millions of men and their partners, that I decided to talk about it publicly.” It was a little embarrassing; that was the point. In the intervening years, Viagra steered away from talking much about sex in its TV ads: its most recent campaign had showed ruggedly capable men at work, and alone.

The new ad, however, gets remarkably specific.

The problem under review is “not just getting an erection but keeping it”—the woman says this twice in less than a minute. The suggestion is that male sexual performance isn’t an all-or-nothing proposition but something that exists on a continuum—and it implies that men could be performing better. In another context, this plain talk about erections might have been the beginning of a more comprehensive, and truly honest, discussion about sex: it might have included the psychological and relational aspects of sexual experience; it could have suggested to men that sex wasn’t a sporting event, and that it need not be judged in terms of wins and losses; and it might have included the voices of real women. Here, the solution to a complicated issue remains simple: get yourself a prescription.

Recent Dish on Viagra here.

The View From Your Window

Dogs vs Cats: The Great Debate, Ctd

In a recent Guardian live chat, the frequently-entertaining pop philosopher Slavoj Zizek added his two cents:

What do you think we can learn from cats, if anything?

Nothing. I like to search for class struggle in strange domains. For example it is clear that in classical Hollywood, the couple of vampires and zombies designates class struggle. Vampires are rich, they live among us. Zombies are the poor, living dead, ugly, stupid, attacking from outside. And it’s the same with cats and dogs. Cats are lazy, evil, exploitative, dogs are faithful, they work hard, so if I were to be in government, I would tax having a cat, tax it really heavy.

Much, much more Dish discussion of dogs vs cats here.

The Language Of Creative Pairs

In an excerpt from his new book, Powers of Two: Finding the Essence of Creation in Creative Pairs, Joshua Wolf Shenk describes the ways individuals in creative partnerships communicate:

When the writer David Zax visited The Daily Show to profile Steve Bodow, Jon Stewart’s head writer (and now the show’s executive producer), Zax could understand only a small fraction of their exchanges, given the dominance of “workplace argot and quasi-telepathy.” “If you work with Jon for any length of time, you learn to interpret the shorthand,” Bodow said. For example, Stewart might say: “Cut the thing and bring the thing around and do the thing.” “ ‘Cut the thing’: You know what thing needs to be cut,” Bodow explained. “ ‘Bring the thing around’: There’s a thing that works, but it needs to move up in order to set up the ‘do the thing’ thing, which is probably the ‘blow,’ the big joke at the end. It takes time and repetition and patience and frustration, and suddenly you know how to bring the thing around and do the thing.”

I’ve interviewed many pairs and seen a variety of styles. Some talk over each other wildly, like seals flopping together on a pier, and some behave with an almost severe respect, like two monks side by side. (Watch a video of Merce Cunningham and John Cage for an illustration.) But regardless of a pair’s style, I usually came away feeling like I had just met two people who were, while inimitable and distinct, also a single organism.

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 153 followers