Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 12

January 26, 2015

Why Berlin Meant Boys

In a review of Robert Beachy’s Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity, Alex Ross ponders why the city proved a relatively hospitable place for a thriving gay subculture that emerged at the turn of the 20th century. One reason? A deep and abiding connection between Romanticism and German culture:

Close to the heart of the Romantic ethos was the idea that heroic individuals could attain the freedom to make their own laws, in defiance of society. Literary figures pursued a cult of friendship that bordered on the homoerotic, although most of the time the fervid talk of embraces and kisses remained just talk.

But the poet August von Platen’s paeans to soldiers and gondoliers had a more specific import:

“Youth, come! Walk with me, and arm in arm / Lay your dark cheek on your / Bosom friend’s blond head!” Platen’s leanings attracted an unwelcome spotlight in 1829, when the acidly silver-tongued poet Heinrich Heine … satirized his rival as a womanly man, a lover of “passive, Pythagorean character,” referring to the freed slave Pythagoras, one of Nero’s male favorites. Heine’s tone is merrily vicious, but he inserts one note of compassion: had Platen lived in Roman times, “it may be that he would have expressed these feelings more openly, and perhaps have passed for a true poet.” In other words, repression had stifled Platen’s sexuality and, thus, his creativity.

Gay urges welled up across Europe during the Romantic era; France, in particular, became a haven, since statutes forbidding sodomy had disappeared from its books during the Revolutionary period, reflecting a distaste for law based on religious belief. The Germans, though, were singularly ready to utter the unspeakable.

In an interview about his book, Beachy sizes up just how remarkable such an outpost of gay culture was:

I think there probably had never been anything like this before and there was no culture as open again until the 1970s. So it’s really not until after Stonewall that one sees this sort of open expression of gay identity or homosexual identity – lesbian identity. … [T]here was this proliferation of publications that started almost immediately after the founding of the Weimar Republic and it continued really right down to 1933 until the Nazi seizure of power. So I think it’s really important to emphasize these publications because they were sort of the substrate, in a certain way, of this culture. They advertised all sorts of events, different kinds of venues and they also attracted advertisers who were really appealing to a gay and lesbian constituency, and that’s also really startling, I think.

“They Think, Therefore I Am”

Yatzchak Francus has discovered for himself that “having recovered from a brain injury is vastly different from having recovered from any other injury”:

No one thinks that a broken leg or a kidney stone or pneumonia fundamentally changes the essence of who you are. But when you’ve had a brain injury, people don’t believe that you are quite the same, although no one will actually say so. Perhaps it is the expression of a universal personal terror. The brain is who we are in the most fundamental sense. We are what we think, and we think with our brain. Not for nothing does Descartes’ summation endure.

The perceptions of my injury endure as well.

Although I have been fully back to normal for close to eight months, “How are you feeling?” continues to supplant “Hello” as the greeting of choice. Sometimes, it seems I hear the question at 15-minute intervals, as I did in the hospital. I half-expect the rest of the ICU script to follow: “Can you smile for me? Can you stick out your tongue? Can you hold up your arms up as if you’re holding a pizza box? Can you tell me what month it is?” When I decline a glass of wine at a holiday party, my host exclaims, “Of course, you have restrictions.” When my parents phoned a few minutes before Yom Kippur because I had forgotten to call them, I could hear the barely-suppressed panic in their voices, their improbable fear of a persistent vegetative state overwhelming the prosaic reality that the day had simply gotten away from me.

The Meaning Of ’90s Sitcoms, Ctd

Many readers aren’t buying Ruth Graham’s view that Friends, and especially Chandler, were homophobic:

I’m sorry, but Friends is mocking homophobia, not displaying it. As a soon-to-be married gay man, I find the idea that this relatively recent show being representative of some benighted era to be an example of ridiculous outrage-mongering.

Another sees “no nastiness in the Chandler bits”:

They aren’t so much about the fear of being gay as they are part of a larger theme of the character – his insecurity – which plays itself out in a number of ways.

Another reader:

First, I grow tired of peeling apart 1994 shows with 2015 sensibilities. Second, the author of that piece has not acknowledged a major part of Chandler’s story:

His father abandoned him. There is no “loving, involved” father, just one who announced he was leaving the family. Whose bed he was leaving for is immaterial.

As for the gay-panic, this would have been the early 1980s when Mr. Bing left. They were in wealthy, WASPy Long Island. Plenty of gossip for a pre-teen boy to deal with. But no, let’s hate the character. (I can tell you that Ruth Graham hasn’t responded to numerous complaints about this in the comment sections. It’s a shoehorning of an agenda onto a popular character and then a cowardly retreat.)

At some point, we have to make a decision to take older shows as they are. Picking them apart now is a miserable experience.

Another piles on:

Ruth Graham reminds me of the character on Friends played by Brooke Shields, who didn’t know the difference between TV/entertainment and real life.

One more reader’s take:

The fear of being thought gay was (and still is) one of the key comic motifs of Two and a Half Men, yesterday’s most popular network sitcom, and of The Big Bang Theory, today’s most popular one. And, of course, how can we ignore the Seinfeld “not that there’s anything wrong with that” episode? In fact, I think it’s fair to say that this is one of the eternal comic themes of American mainstream comedy, just like stupid husbands, wives who don’t want to have sex, children who disdain their parents’ cluelessness, etc.

So I don’t see this as truly homophobic. It’s sitcom comedy, which in its classic form is based in cliches and plays on our fears and desires. Even Will & Grace, considered the breakthrough network show for gays, frequently played up the comic themes of Will acting in a cliched gay manner and Grace being the classic “fag hag”. If we can’t laugh at cleverly-done comic pieces like this without being considered homophobic, then we’ve all lost our senses of humor.

“An Atheist’s Week Of Dish”

A reader spells it out:

Monday: Man, these guys work hard.

Tuesday: Pretty good opinion piece.

Wednesday: Wow, that was an amazing amount of great content.

Thursday: Sully’s a great fucking editor.

Friday: Okay, that really made me think.

Saturday: Totally worth the subscription.

Sunday: Oh, for fuck’s sake.

That’s not a complaint. If only everyone nailed six out of seven.

The Limits Of New Scientism

Steven Shapin explores the question of whether or not science can make us good. He notes that while modern iterations have shorn religion of its claims to authority, “the ambitions of the new scientism may be self-limiting”:

Different scientists draw different moral inferences from science. Some have concluded that it is natural and good to be ruthlessly competitive; others see it natural to cooperate and trust; still others embrace the lesson of the naturalistic fallacy and oppose the project of inferring the moral from the natural. That was the basis of T. H. Huxley’s skepticism in 1893:

The thief and the murderer follow nature just as much as the philanthropist. Cosmic evolution may teach us how the good and the evil tendencies of man may have come about; but, in itself, it is incompetent to furnish any better reason why what we call good is preferable to what we call evil than we had before.

Nor does the new scientism solve the long-standing problem of whom to trust. Just like every modern scientist, the advocates of the new scientism do what they can to sell their wares in the marketplace of credibility. And here the new scientism, for all its claims that there is a way science can make you good, shares one crucial sensibility with its opponents: having secularized nature, and sharing in the vocational circumstances of late modern science, the proponents of the new scientism can make no plausible claims to moral superiority, nor even moral specialness.

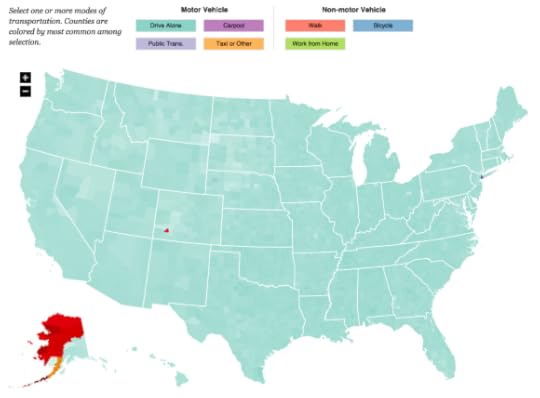

Map Of The Day

Nathan Yau made a zoomable map of how we commute:

He zeros in on some outliers:

As you might expect, a lot of people take public transportation to work in the New York City area, along with Washington, D.C. In New York county, an estimated 58% of workers use public transportation, and in the former, 38%. In several counties in Alaska, more people use “other” forms of transportation that isn’t a car, van, or truck. I’ll venture a guess that’s it’s something like snow mobile instead.

In San Juan county, Colorado, it looks like carpooling is a bit more common. However, San Juan has a small population and a large margin of error, so it’s tough to say if carpooling really is more common than driving alone. I’m not sure how much I want to trust estimates where the margin of error is almost equal to the rate. Likely an outlier in sampling more than one in reality.

Take driving alone out of the comparison, and the areas where public transportation is most common is more obvious.

You can also look at public transportation by itself to similar effect, but I think the comparisons make the geography more interesting. For example, you see more people working from home in the midwest, where much of the land is devoted to farming. In many areas, people just walk to work.

Play around with the map yourself here.

Why Do We Call Terrorists Cowards?

Reviewing Chris Walsh’s Cowardice: A Brief History, Kyle Williams offers an answer:

The first and perhaps most visceral is that, short of obscenities, it is one of the nastiest words that can be wielded against someone—and has been for a long time. Cowards are anathema in the Revelation of St. John, among the first to be damned to the lake of fire, and among the most despicable in Dante’s Inferno. Samuel Johnson confirmed the prejudices of ages before and after him when he wrote that cowardice is “always considered as a topic of unlimited and licentious censure, on which all the virulence of reproach may be lawfully exerted.” One wonders what could be worse.

Walsh also suggests that the term provides comfort to Americans. Believing that terrorists are cowardly may assuage the fear of terrorism. “If they were cowardly then they were scared too—vulnerable and weak,” he writes. “And thinking them weak somehow made another new phrase—‘Boston Strong’—seem more convincingly true.” Terrorism targets innocent civilians, relies on secrecy and infiltration. It stands, at least rhetorically, in contrast to the more open apparatus of the American nation-state and its military might.

January 25, 2015

Art After Auschwitz

Ryu Spaeth reviews Suspended Sentences, the recently-translated collection of works by Patrick Modiano, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature last year, noting the author’s interest in Paris during the Nazi occupation. He considers how Modian exhibits “the postwar generation’s wariness of the redemptive power of art”:

Modiano expresses this in an episode in “Afterimage” in which [a character, the photographer Francis] Jansen, newly released from the transit camp for Jews that should have sent him to his doom, searches for the relatives of a fellow detainee who wasn’t so lucky. He finds none of them, “[a]nd so, feeling helpless, he’d taken those photos so that the place where his friend and his friend’s loved ones had lived would at least be preserved on film. But the courtyard, the square, and the deserted buildings under the sun made their absence even more irremediable.”

In other words, there are only so many people the artist can save. It is as if the sum effect of Suspended Sentences is a gesture at a silence that rings far louder than the words on the page — the silence of the millions of souls who died in the Holocaust, and broader still, the silence of a ceaseless loss that stretches across millennia and defines our time on Earth. Suspended Sentences, then, is a purposeful act of misdirection, a candle that only serves to emphasize the surrounding darkness. As the narrator in “Afterimage” says of Jansen, “A photograph can express silence. But words? That he would have found interesting: managing to create silence with words.”

(Photo by Flickr user slgckgc)

Playing God

Will Wiles explores the phenomenon of “god games,” like Banished, “in which the player guides a small group of people in building a small village, which with careful guidance can become a small town.” He contemplates what their growing popularity suggests about players:

Post-apocalyptic scenarios often have undertones of amoral consumerist wish-fulfilment, in which we roam the shopping malls and other treasure houses of the modern world and take whatever we want, blasting anyone who gets in our way. Survival games are, at least, a little more honest about the challenges of such a situation and an individual’s chances within it. But perhaps it’s better just to focus on what this phenomenon means for this immature art form. With technological limitations falling away, game design might be exhausting the possibilities of more and increasingly discovering the power of less.

At the heart of the new digital melancholy – wrapped in all that beauty – is primal simplicity, the basic animal equation: eat, don’t get eaten, keep going. The value of that simplicity, the playability of it, perhaps we could even say the fun of it, is watching the unexpected ways this elemental calculus can work itself out. And there is more watching involved. Vulnerability imposes a measure of passivity – in some situations, for instance, the only workable strategy might be to wait for danger to pass, to hide behind a hedge, to stay in the shelter until dawn or nightfall – so the environment and the atmosphere become more important, they are not just a Niagara of garish detail to be rushed past. There is a world to be experienced, and we must learn our place in it.

The Landscape Of Loss

In an interview worth reading in full, the poet Christian Wiman explores how being raised in West Texas has shaped his thinking:

Loss is conspicuous in “Keynote”: “I had a dream of Elks, / antlerless but arousable all the same, // before whom I proclaimed the Void / and its paradoxical intoxicating joy.” The “infinities of fields” also bring a “satisfaction of a landscape / adequate to loss.” Did West Texas instigate this obsession of a recursive Void?

Addicted to loss? Maybe once, long ago. Then I got a good, deep miasmic draught of the real thing and have been nauseated ever since. But the connection between that landscape and loss is, for me, quite real. I wrote a novel once (it died in a drawer) in which a character says that the landscape of West Texas is a terrible landscape for depression, which is a “moist” emotion (she’s a psychiatrist). The desert just crushes that, makes it seem somehow impossible. Grief, though, has its place in such emptiness, that endless sense of something missing—God, for instance. You wonder why there’s so many right-wing wing-nuts grieving God in the deserts of the world (righteous wrath is simply the fumes of unacknowledged grief). I’ve solved the quandary, I tell you.

Subscribers can read our Deep Dish essay on Wiman here, and listen to a podcast with him here.

(Image from Edward Musiak)

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 153 followers