Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 113

October 26, 2014

The Smears Of The Matthew Shepard Foundation

It’s well worth reading a story in the Guardian/Observer today about the famous and horrifying murder of Matthew Shepard. The Guardian is a left-leaning paper, but it is not American and therefore has some interest in the actual truth of the affair, as opposed to the propaganda. And it largely echoes the superb reporting of Steve Jimenez, whose book, “The Book of Matt“, proved to anyone not blinded by agit-prop that this awful crime was committed not be “redneck” strangers, but by a couple of Shepard’s acquaintances, one of whom had been his lover, who were eager to get access to crystal meth they believed Shepard had access to. (For the full Dish coverage of the book see here.)

The author, Julie Bindel, does some reporting of her own. She quotes, for example, the cop who nabbed one of the killers:

“I believe to this day that McKinney and Henderson were trying to find Matthew’s house so they could steal his drugs. It was fairly well known in the Laramie community that McKinney wouldn’t be one that was striking out of a sense of homophobia. Some of the officers I worked with had caught him in a sexual act with another man, so it didn’t fit – none of that made any sense.”

Then this:

Ted Henson is a former lover and long-term friend of Matthew’s. The pair originally met when Matt was growing up in Saudi Arabia. Henson told me he believes that The Book of Matt is “nothing more than the truth” and that he was “never certain” that the murder was an anti-gay hate crime. “I don’t know why there is so much hostility towards Steve,” he told me. “Matt would not have wanted to be seen as a martyr, but would have wanted the truth to come out.”

What’s truly remarkable about this book is not that, like many before it, it exposes the truth behind a useful myth. It is the reaction of the gay establishment to these difficult truths. The Book Of Matt insists on the horrifying nature of the crime; it had no pre-existing agenda; it’s written by an award-winning reporter who is also a gay man. (The Wyoming Historical Society also gave it an award.) What it does is expose a real problem in the gay male world – especially at the time of the murder: the nexus of sex and meth that destroyed and still destroys so many lives.

So what does the Matthew Shepard Foundation say in response to the book?

I asked for a reaction regarding the book, but was sent a pre-prepared statement by executive director Jason Marsden, who was a friend of Matthew’s. “We do not respond to innuendo, rumor or conspiracy theories,” reads the statement first issued when The Book of Matt was published. “Instead we remain committed to honoring Matthew’s memory and refuse to be intimidated by those who seek to tarnish it.”

They won’t even address the book. Recently, an editorial in the Casper Star Tribune, without addressing any of the factual claims in the book, continued to smear Jimenez, equating the book’s thesis to conspiracy theories about the moon-landing and describing the paperback edition as “poison made portable.” The New York Times, for its part, refused to review it. Those who made a small fundraising fortune off the myth – like the Human Rights Campaign (natch) – will never acknowledge the truth. But the book is its own best defense. The paperback has a new Afterword by Jimemez. You can buy it here – and I highly recommend that you do.

End-Of-Life Literature

In an interview about his new book, Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End, the surgeon and writer Atul Gawande runs down the literary influences that inform his approach to medicine:

What books most influenced your decision to become a doctor, and your approach to medicine? Who are your favorite physician-writers?

I have so many: Anton Chekhov, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, John Keats, Walker Percy. Mikhail Bulgakov was famous for “The Master and Margarita,” but his “Country Doctor’s Notebook” is fascinating, too. So is William Carlos Williams’s “Doctor Stories.” When I was in medical school, a trio of doctors who’d come out with nonfiction books around that time awoke me to the concrete, practical idea that one could be both a physician and attempt to write seriously: Oliver Sacks, Sherwin Nuland and Abraham Verghese. I reread Lewis Thomas constantly. Richard Selzer’s essays on his life as a surgeon — for instance, “Mortal Lessons,” “Confessions of a Knife” and “Letters to a Young Doctor” — can seem overwritten, but they have stayed with me for years now. These writers all transcend the term “physician-writers.” They’re just writers, telling us about the experience of being human.

What book would you most recommend to an aspiring doctor today?

Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilyich.” It’s the best portrayal of sickness and suffering I have ever read — minutely observed, difficult and still true a century and a quarter later.

Great writing on illness and mortality extends vastly beyond works by doctors, and I can’t let the opportunity go without mentioning at least a few more of my non-doctor favorites: There’s Anatole Broyard’s amazing memoir of his own dying, “Intoxicated by My Illness,” Anne Fadiman’s “The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down” and Joan Didion’s “The Year of Magical Thinking.” Oh, and Sylvia Plath’s “The Bell Jar,” Ken Kesey’s “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and William Styron’s “Darkness Visible.” And I can’t leave out Thomas Mann’s “The Magic Mountain” or Virginia Woolf’s “On Being Ill.” These all deserve readers of any kind. But about one in five of us work in health care in some way, and we have a particular responsibility to understand what people experience when their body or mind fails them. Our textbooks and manuals aren’t enough for that task.

Gavin Francis notes how Gawande’s personal story informs his perspective on end of life care:

Towards the end of the book, he tells the story of his own father’s decline and death from a tumour of the spine. His experience as a surgeon melts away and he finds himself navigating infirmity and dependency as a son, rather than as a clinician. It’s the worried son, not the Boston surgeon, who reflects on the qualities he values in the doctors treating his father: not bullish arrogance, but acknowledgement of uncertainties and a willingness to accept risks. He finds doctors communicate most effectively when they jettison the position of detached, clinical observers and talk in terms of how they feel: “I am worried about your tumour because … ” Often the bravest and most humane decision, he realises, is to do nothing at all.

When time becomes short, Gawande has the presence of mind to ask his father: “How much are you willing to go through just to have a chance of living longer?” The answer helps guide his father to a relatively peaceful death in the arms of his family, as opposed to a technologised end on an intensive care unit. The message resounding through Being Mortal is that our lives have narrative – we all want to be the authors of our own stories, and in stories endings matter. Doctors and other clinicians have to get better at helping people with their endings, otherwise more and more of us will end our lives babbling behind shining doors.

Recent Dish on end-of-life concerns here, here, and here.

The Sound Of Guilt

Reviewing Peter Sellars’ “already legendary” staging of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, which was performed in New York City earlier this month, Alex Ross explores the distinctive theological vision that informs the oratorio:

Martin Luther, in a treatise on the Crucifixion in 1519, had grim tidings for those of his followers who wished to lay the blame for Christ’s death entirely on the Jews. You killed Jesus, Luther told them: “When you see the nails piercing Christ’s hands, you can be certain that it is your work.” Luther’s message served as a warning to those who felt secure in their faith, their virtue, their worldly position; guilt for the crime at Golgotha is ubiquitous, seeping forward in time. Dietrich Bonhoeffer echoed the point in the early twentieth century, emphasizing how the Passion story shatters the illusions of a prosperous, self-satisfied modern society: “The figure of the Crucified invalidates all thought which takes success for its standard.”

Lutherian severity lies at the core of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, which, scholars have argued, takes that 1519 treatise as a model. The immensity of Bach’s design—his use of a double chorus and a double orchestra; his interweaving of New Testament storytelling and latter-day meditations; the dramatic, almost operatic quality of the choral writing; the invasive beauty of the lamenting arias, which give the sense that Christ’s death is the acutest of personal losses—has the effect of pulling all of modern life into the Passion scene. By forcing the singers to enact both the arrogance of the tormentors and the helplessness of the victims, Bach underlines Luther’s point about the inescapability of guilt. A great rendition of the St. Matthew Passion should have the feeling of an eclipse, of a massive body throwing the world into shadow.

Why We Long For The Zombie Apocalypse

As Halloween approaches, Paul Pastor offers a theological gloss on monster stories, calling them “a quick route to our hearts” and holding that “our fears shed light on our loves, on our priorities, on our hopes, on the thousand things that form who we are”:

Our monster stories reveal deep-set fears, but they also unveil our hopes. In the popular modern zombie flick, for example, we see that even in the total collapse of human society, we can hope for not only survival, but for community, for beauty, for something more than the Western dreams of brainless consumption and the cannibal exploitation of our neighbors. We can find a sense of belonging, of dignity. Modern Westerners long for a satisfying level of self-sufficiency, for friends that we could trust our life with, for a sense of clear purpose, however bleak the surrounding world might be.

In America, where our folk culture is steeped in red-hot brimstone and rapture theology, we both dread and long for apocalypse. We’re afraid of being killed or “left behind,” but secretly believe that we’ll be one of the chosen few who survive the end, to help usher in a new age. This apocalyptic narrative has extended far beyond Christianity or pseudo-Christian cults. It’s embedded firmly in our cultural imagination regardless of our collective American faith or lack thereof. As such, the modern zombie tale is a classic example of apocalypse in the 20th century. We long for a reset button, for upheaval that will leave something better than what we have now when the dust settles.

(Image: The Head of Medusa by Peter Paul Rubens, circa 1618, via Wikimedia Commons)

“You Have Every Reason To Be Depressed”

Art Rosman re-reads Walker Percy’s mock-self-help book, Lost in the Cosmos, noting that Percy “does not think that depression is merely a problem to be medicated away, but rather a rational response to the state of our world”:

Let’s start with how Percy takes a quick stock of modern life by answering the question why so many people are depressed:

Because modern life is enough to depress anybody? Any person, man, woman, or child, who is not depressed by the nuclear arms race, by the modern city, by family life in the exurb, suburb, apartment, villa, and later in a retirement home, is himself deranged.

We could add any number of deranged situations to the list: the growing income inequality gap, any number of looming ecological disasters, terrorism, the disappearance of the extended family, Ebola, AIDS, the fertility crash, and so on.

Rosman goes on to cite a brilliant passage from Percy’s book that elaborates on this notion:

Now, call into question the unspoken assumption: something is wrong with you. Like Copernicus and Einstein, turn the universe upside down and begin with a new assumption. Assume that you are quite right.

You are depressed because you have every reason to be depressed. No member of the other two million species which inhabit the earth—and who are luckily exempt from depression—would fail to be depressed if it lived the life you lead. You live in a deranged age—more deranged than usual, because despite great scientific and technological advances, man has not the faintest idea of who he is or what he is doing.

Begin with the reverse hypothesis, like Copernicus and Einstein. You are depressed because you should be. You are entitled to your depression. In fact, you’d be deranged if you were not depressed. Consider the only adults who are never depressed: chuckleheads, California surfers, and fundamentalist Christians who believe they have had a personal encounter with Jesus and are saved for once and all. Would you trade your depression to become any of these?

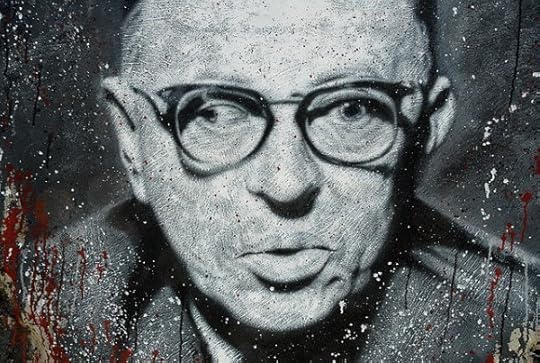

Get Sartre

We recently looked back at why Sartre turned down the 1964 Nobel Prize in Literature. Now, Stuart Jeffries elaborates on the philosopher’s refusal and considers why “so much of his lifelong intellectual struggle and his work still seems pertinent” today:

When we read the “Bad Faith” section of Being and Nothingness, it is hard not to be struck by the image of the waiter who is too ingratiating and mannered in his gestures, and how that image pertains to the dismal drama of inauthentic self-performance that we find in our culture today. When we watch his play Huis Clos, we might well think of how disastrous our relations with other people are, since we now require them, more than anything else, to confirm our self-images, while they, no less vexingly, chiefly need us to confirm theirs. When we read his claim that humans can, through imagination and action, change our destiny, we feel something of the burden of responsibility of choice that makes us moral beings. …

In his short story Intimacy, we confront a character who, like all of us on occasion, is afraid of the burden of freedom and does everything possible to make others take her decisions for her. When we read his distinctions between being-in-itself (être-en-soi), being-for-itself (être-pour-soi) and being-for-others (être-pour-autrui), we are encouraged to think about the tragicomic nature of what it is to be human – a longing for full control over one’s destiny and for absolute identity, and at the same time, a realisation of the futility of that wish.

The existential plight of humanity, our absurd lot, our moral and political responsibilities that Sartre so brilliantly identified have not gone away; rather, we have chosen the easy path of ignoring them. That is not a surprise: for Sartre, such refusal to accept what it is to be human was overwhelmingly, paradoxically, what humans do.

(Photo of painted portrait of Sartre by thierry ehrmann)

Mental Health Break

Filmmaker Vince Di Meglio edits together twenty-nine films to showcase the stunning visuals of silent-film legend Buster Keaton:

Use Your Illusion

Daniel Dennett applauds Alfred R. Mele’s Free: Why Science Hasn’t Disproved Free Will, which picks apart a range of experiments from recent decades that purportedly show free will is an illusion:

A curious fact about these forays into philosophy is that almost invariably the scientists concentrate on the least scientifically informed, most simplistic conceptions of free will, as if to say they can’t be bothered considering the subtleties of alternative views worked out by mere philosophers. For instance, all the experiments in the [neurologist Benjamin] Libet tradition take as their test case of a freely willed decision a trivial choice—between flicking or not flicking your wrist, or pushing the button on the left, not the right—with nothing hinging on which decision you make. Mele aptly likens these situations to being confronted with many identical jars of peanuts on the supermarket shelf and deciding which to reach for. You need no reason to choose the one you choose so you let some unconscious bias direct your hand to a jar—any jar—that is handy. Not an impressive model of a freely willed choice for which somebody might be held responsible. Moreover, as Mele points out, you are directed not to make a reasoned choice, so the fact that you have no clue about the source of your urge is hardly evidence that we, in general, are misled or clueless about how we make our choices.

Similarly, Daniel Wegner’s case amounts to generalising the surprising discovery that in Ouija-board situations, people can often be made to feel they are the authors of acts that are in fact caused by the experimenter’s accomplice. Since in these rather artificial and strange circumstances we can be misled into thinking retrospectively that we chose to act when in fact we were manipulated into action, Wegner believes that it must follow (mustn’t it?) that we are never authoritative about the authorship of our acts. There are some complications to Wegner’s case, but this non-sequitur lies at the heart, and Mele has no difficulty providing evidence of cases in which our knowledge of our own reasoned choices is unassailable.

Marble In Motion

The above excerpt from Yuri Ancarani’s documentary Il Capo depicts the process of extracting marble from a quarry with unusual beauty:

Ancarani was captivated by the otherworldly landscapes of the quarry. He spent nearly a year filming on Monte Bettolgi, in the Carrara region of the Apuan Alps, in Northwest Italy, eventually deciding to focus his film on the hypnotic, and rather dramatic moment when the monumental marble blocks are freed from the mountainside, and fall to the ground with an earth-shattering thud.

Ancarani says of his work:

In a lot of documentaries about the marble quarries, the quarrymen are shown as Neorealistic archetypes, tough guys made of sweat and swear words. I, on the other hand, admire their practical intelligence: it is a form of elegance that can teach us a lot, and which my head quarryman possesses: he is a man who has style in his gestures and manners. In such a tough and dangerous environment, I wanted to highlight an aspect of delicacy.

(Hat tip: Kottke)

A Poem For Sunday

Dish poetry editor Alice Quinn writes:

I found this declaration on the website of the Poetry Foundation, where so many satisfying capsule biographies of poets can be found along with reference to relevant and available scholarship. “Modern readers looking for [Adelaide] Crapsey’s work are hard-pressed to find it in any anthology printed after 1950.” That’s why the recent publication of Modernist Women Poets: An Anthology, edited by Robert Hass and Paul Ebenkamp is so significant today.

In her preface to the book, C.D.Wright notes that Crapsey, who was diagnosed with tuberculosis of the brain lining in 1911 when she was thirty-three, “was not afforded a long lifeline. She went to college, studied in Rome and taught at Smith, but mostly she watched the world from her Brooklyn window and kept a bracing seasonal vigil over her own dying. She applied an economy of words uncommon for her time coupled with a stoic yet revealing level of restraint.” We’ll be featuring selections from Verse, a well-regarded collection of sixty-three poems, published shortly after her death in 1915.

Three short poems from Adelaide Crapsey:

“November Night”

Listen..

With faint dry sound,

Like steps of passing ghosts,

The leaves, frost-crisp’d, break from the trees

And fall.

“The Guarded Wound”

It it

Were lighter touch

Than petal of flower resting

On grass, oh still too heavy it were,

Too heavy!

“The Warning”

Just now,

Out of the strange

Still dusk.. as strange, as still..

A white moth flew. Why am I grown

So cold?

(From Modernist Women Poets: An Anthology © 2014 by Robert Hass and Paul Ebenkamp. Reprinted by permission of Counterpoint Press. Photo by Martin Fisch)

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 153 followers