Robin Rowland's Blog, page 2

May 10, 2024

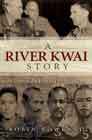

Rex Murphy, dead at 77, from astute commentator to bitter curmugeon

Rex Murphy shots for new Point of View opening 2007 (Robin Rowland)

Rex Murphy shots for new Point of View opening 2007 (Robin Rowland)Rex Murphy, one of Canada’s best known, loved and hated TV commentators and columnists has died at 77.

I have mixed feelings about his passing.

I was Rex Murphy’s online editor from 1998 to 2003 when I was web producer for CBC’s The National.

In those days his writing was superb and he had incitive often bighting insight into Canadian politics even if it was from a small C Conservative point of view. He was good to work with and did take my suggestions to make the online version of his TV opinion better for the computer screen.

After I moved on to become CBC News photo editor, CBC News management foolishly took down the archive of his early columns to in redesign of the National website but mostly to save server space there were hundreds of complaints. (As one former colleague commented on my Facebook post “Saving server space by erasing text files??? Argh”)

Although not everyone shares the sentiment, several former CBC colleagues, in those days, Murphy was generally good to work with, with a sense of humour and a good joke (even if the jokes weren’t entirely politically correct, then they were done in good humour and with out malice. At that time)

For those who commented on my Facebook post which this blog is based on, Murphy’s commentaries were must listening in the 90s and early 2000s, but after that he changed from a “gadfly” and “contrarian” who became unrecognizable with his hard right. often hate filled rants. He was the host of Cross Country Checkup for 21 years.

In later years, however, I believe that he had lost all human perspective when it came to saving all life including human life on this planet from the coming climate catastrophe. He also became more extreme in his conservative views.

Murphy’s transformation from a moderate conservative to a raging ranter was, unfortunately, typical of many in the boomer generation, angered and disturbed by the changes in society. For years there were memes posted by hard right supporters on Facebook and X “Rex Murphy for Prime Minister.”

Murphy was also accused of being in the pocket of the oil industry for taking paid speaking engagements. (CBC audio) Although he said no one told him what to think or write.

His obituaries note that he supported the oil and gas industry because it helped save the Newfoundland economy after the collapse of the cod fishery. I also know that he was enraged by the environmental and animal rights continued efforts to ban the seal hunt including using images of white coat seal pups after that harvest was banned.

One wonders if he was wilfully blind to the environmental damage caused to Newfoundland and Labrador by over exploitation that led to the collapse of the cod fishery and the damage to the province by climate change?

To me the most egregious example of Murphy’s bias in later years was when during the Northern Gateway pipeline controversy, as host of Cross Country Checkup, he held a series of celebratory town halls in oil town Fort McMurray but never bothered to bring the show to Kitimat and northwestern British Columbia to tell the other side of the story. This was a profound failure of Cross Country Checkup’s producers and CBC News management at the time. That lack of balance was also a direct violation of CBC Standards and Practices. (By the time of that broadcast I had retired, moved to Kitimat, and was freelancing for various news agencies including CBC News)

When I was CBC News photo editor, I took a series of photos of Rex against a green screen that were used for an animated opening for his opinions on the National. He couldn’t resist making silly faces at times.

CBC obituary: Writer and journalist Rex Murphy dead at 77

National Post obituary: Rex Murphy, the sharp-witted intellectual who loved Canada, dies at 77

Rex Appeal, 1996 profile in the (former) Ryerson Review of Journalism by Mariam Mesbah

The post Rex Murphy, dead at 77, from astute commentator to bitter curmugeon first appeared on Robin's Weir.

August 21, 2023

The whales that travel from Kitimat to Lahaina

Tanu in Bishop Bay, August 28, 2017 (Robin Rowland)

There is an interesting connection between Kitimat and Lahaina the site of the Maui fire disaster last week.

After I saw the item on CBS Morning Sunday News last Sunday about the Happy Whale tracking site, I uploaded all the photos I captured of humpback whales in Douglas Channel over the past few years.

Of the seven whales that were identified, two stand out because of the recent events.

According to the tracking system a humpack named “Tanu” with the scientfic desginations PWF-NP_2551

SPLASH-460100, which I photographed on August 28, 2017 at Bishop Bay, was seen on January 29, 2023 off Laihani in Maui where the fires destroyed the town last week and also off Maui close to Lahaina on March 11 and 12 2020.

Happy Whale tracking maps

There’s a good chance that Tanu may be in Douglas Channel right now as I post this on August 28, 2023.. Other sightings were off Gil Island September 2, 2012 Blue water adventures, in Consave Passage August 9, 2006 North Coast Caetacean Society and off Port McNeil August 8, 2004 DFO.

A second whale, unnamed but disignated BCY0971, I photographed off Eagle Bay also on August 28, 2017 and by the North Coast Caetacean Society off Gil Island on August 31, 2015 was seen off Lahaina on March 6, 2022.

You can check out my other humpback encounters

Data is still sparse but it appears that many of the humpbacks in the Channel may be choosing to come direct to Douglas Channel rather than cruising up and down the coast. If you have humpback photos, you can register and upload your own humpback photos to support that tracking at happywhale.com

The post The whales that travel from Kitimat to Lahaina first appeared on Robin's Weir.July 9, 2023

Is it Kitimat or Star Trek’s Delta-Vega?

The Star Trek matte painting of Delta-Vega beside a shot of the LNG Canada facility. (Star Trek/Deslu/Paramount; LNG Canada)

“There’s something familiar about this place.”

I was on a bus tour of Kitimat’s giant $40 billion LNG Canada facility on Saturday, July 8.

I’ve never been on site, but had this strange feeling I had seen it before.

The LNG Canada Liguified Natural Gas project, is the largest industrial construction project in Canadian historythe , which, of course, is still under construction with the completion of the two “trains” to process the natural gas into liquid form so the volume shrinks so it can be loaded into LNG tankers for tansport to Asia, with each shipment worth millions of dollars.

The project is somewhat controversial, given a number of factors, such as whether or not LNG which is bascially methane, is a transition fuel to wean the world off coal and oil or whether it is a dangerous addition to the atmospheric crisis since methane is itself a green house gas. Other controveries are the emmissions from the plant itself (low by previous standards) and the increase in ship traffic on Douglas Channel. Local indigenous First Nations are split on the construction, with some opposing the Coastal Gas Link pipeline that will bring the natural gas from northern British Columbia while many indigenous people and communities are prospering from the jobs and other opportunities to get out of poverty that come from the project.

To actually see the huge project, albeit on a three hour bus tour, the visitor will briefly leave the controversies behind, as you are awestruck by the gargantuan size of the facility and the complexity of the various components of the project. For someone who was a kid in the 50s and 60s, the LNG Canada project really is something out of the dreams of science fiction of the Golden Age.

As the bus left, Something about Star Trek, I thought.

So here is another strange prescient item for the Star Trek timeline, the Albert Whitlock matte painting of the lithium cracking station on Delta-Vega, created for the second pilot of the Star Trek Original Series Where No Man Has Gone Before.

A full view of matte painting of Delta-Vega from Where No Man Has Gone Before (Star Trek/Deslu/Paramount)

A full aerial view of the LNG Canada plant under construction in June 2023 (LNG Canada),

The units that will process the natural gas are gigantic steel modules, built overseas and brought to Kitimat on large ships. It was those modules that resemble the structures that Albert Whitlock imagined when he created Delta-Vega. Having ships bring the modules across the ocean is again a science fiction story in itself.

One of the giant modules arrives by ship in Kitimat harbour, Jan. 8, 2023 (Robin Rowland)

That does not mean, of course, there won’t be consequences for all this as any good science fiction story would have and still could tell. I will leave that for a future blog

The other interesting science fiction aspect to the tour was the environmetal obligations that the company has under the conditions of the approval that came from the Canadian and British Columbia governments.

The contractor must not only do everything can to mitigate the enviromental damage caused by construction, they are obligated to recreate twice the amount of the environment that was damaged, so that means also restoring the mistakes of earlier generations. That includes restoring Sumgas Creek in the Kildala neighborhood.

As I listened to the upbeat descriptions of our tour guide from the construction prime contractor JGC Corporation and Fluor Corporation – JGC Fluor BC LNG Joint Venture there was another science fiction thought. The restoration is a massive effort at terraforming

No matter what your position is on the LNG Canada project (I have mixed feelings) the expertise and experience gained here could well be a model to restore the environment elsewhere (that is if politicians actually get their act together before it is too late)

(Now if we could only persuade both Paramount and LNG Canada to shoot an episode of Strange New Worlds here in Kitimat  unlikely however but Delta-Vega had to be built before Kirk visited)

unlikely however but Delta-Vega had to be built before Kirk visited)

Another view of the LNG plant under construction in September 2022. (LNG Canada)

The site repainted as the planet Tantalus for the episode Dagger of the Mind. (Star Trek/Desilu/Paramount)

The post Is it Kitimat or Star Trek’s Delta-Vega? first appeared on Robin's Weir.May 12, 2023

BBC Panoroma uses “ADHD Face” in what appears to be a second apparently unethical and disgraceful “investigation”

To be a journalist with undiagnosed Attention Deficit (Hyoperactitity) Disorder is, far too often, to have a career too often is a series of mistakes and failures interspersed with occasional moments of brilliance and perception and only that latter that save that career from being a total disaster.

I spent the first twenty-five years in journalism, in print, radio, television and online, most of it at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, too often wondering what the frig had gone wrong time and time again.

It was one Saturday morning in the fall 1998, reading a newspaper containing a review of a new book on ADD, something I had never heard of, that was a moment of epiphany. As soon as I finished breakfast I jumped up on the Toronto subway to the nearest bookstore and read the book that afternoon.

I called my family doctor and saw her the following week. Luckily she had a friend from medical school who had a pediatric ADD practice who had begun treating adults (since ADD/ADHD is likely genetic parents are often treated alongside their children) and began the usual tests.

The diagnosis was confirmed and I was put on meditation that steadied my brain and likely rebooted my career. Others have not been so lucky, and have seen their hopes, dreams and careers go down in firing flames.

To be an ADHD/ADD journalist is to be in the closet, being open about it could be career destroying. Now that I am semi-retired I have no need to keep that secret, as some journalists I know still keep their condition and life secret.

So this evening I came across a growing Twitter storm over an upcoming episode of BBC Panorama to air on Monday. (That means like everyone else I haven’t seen the episode and probably won’t see it since it is geoblocked)

This this how the BBC describes the episode

There has been a sharp increase in the number of adults asking to be assessed for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The NHS has been overwhelmed by the number of patients looking for a diagnosis. Now thousands of people are turning to private clinics for assessment instead.

Panorama reporter Rory Carson goes undercover as a patient to reveal how some clinics are charging large fees for online assessments, and evidence suggesting diagnoses are being given to almost everyone who books an appointment.

The programme also reveals clinics prescribing powerful medication without carrying out proper checks.

Now those of us in the ADD/ADHD community know that there are clinics, not just in the United Kingdom, that exploit an ADD/ADHD diagnosis. Worse is the unwarranted medication of some children without ADD in some schools in some locations just to keep them in order.

The real story, as the anger on Twitter from people in the UK who are struggling for diagnosis and treatment shows; they are are waiting months, even years for diagnosis and treatment in the failing National Health Service.

That lack of access to proper diagnosis, treatment, medication and counselling is a problem here in Canada where it is often not fully covered by provincial health plans and even care for those who have extended insurance, diagnosis and treatment is not always available or fully affordable.

The situation is often worse in the United States with its health care system, especially for marginalized communities.

The BBC had initially called the episode the ADHD Scandal, but after protests following the initial publicity changed the title to Private ADHD Clinics Exposed.

Changing the title is not enough. The entire premise of the episode where a reporter, Rory Carson, who one may presume doesn’t have ADHD goes undercover to get a false diagnosis, by it appears, giving a practitioner false symptoms, is a complete breach of contemporary journalistic ethics.

When I worked at CBC News, that kind of undercover operation was always approved by the highest levels of news management, so if there are similar policies at the BBC, then the blame for this goes to the top.

Let’s call it what is ADHD Face.

Why in 2023, would a prestigious show like Panorama even think of doing something so unethical and outrageous? Would the producers of Panorama or elsewhere in the BBC do something similar with any other marginalized community? It’s likely that those in Great Britain who can afford to attend and pay for access to private clinics are white and privileged. That, of course, ignores everyone else dependent on the NHS.

With the BBC under increased scrutiny in Great Britain, especially from the Conservatives who want to gut the service, what were Executive Producer Andrew Head and Producer Hannah O’Grady thinking when this idea was discussed and approved in a story meeting?

I am sure that in any organization as large as the BBC there are many reporters and producers who have ADHD. The question is how many are out of the ADHD closet?

In 2023, any reputable and ethical media operation does not send someone who knows nothing about a community to investigate that community.

It is crystal clear from this point of view, that if there are BBC staff open about an ADHD diagnosis they were not consulted or asked for advice. That kind of advice and consultation is now standard in any ethical journalism organizations, mostly with indigenous and communities of colour. It may be more difficult because ADHD is often hidden, but given Panorama’s dubious track record on covering ADD/ADHD, it should have been obvious that they should have reached out.

I did a quick Google search to see what other comments had been posted about this story only to find on the first Google page that Panorama had done a similar hatchet job on ADHD back in 2007, and the BBC Trust found the program was in breach of standards and was told in 2010 to issue an on air apology and withdraw the item

The Trust’s editorial standards committee (ESC) found that the programme, titled What Next for Craig?, failed to uphold the required standards for accuracy and impartiality.

Due to the “serious nature of the breaches”, a full correction and apology will have to be run at the start or finish of the next edition of Panorama on BBC One.

The Trust also ruled that the episode must never be repeated on the BBC or sold to other broadcasters, while all mentions of it must be removed from the BBC website.

“The ESC expects the highest standards from Panorama as BBC One’s flagship current affairs programme, and this programme failed to reach those standards,” said the ruling.

“Due to the serious nature of the breaches the ESC will apologise to the complainant on behalf of the BBC and require the broadcast of a correction….

Panorama also “distorted some of the known facts in its presentation of the findings” and failed to acknowledge “a serious factual error”, said the Trust.

However, the ESC accepted that the makers “did not deliberately produce a programme that they knew to be inaccurate”.”

You would have thought after being hauled over the coals for “not deliberately” making a program that was such a disaster, that Panorama staff should have known better 13 years later.

So far there has been just one comment posted that I could find, posted just a couple of hours earlier, as the Twitter storm erupted. Private ADHD clinics saved me – their demonisation is devastating by Charlotte Columbo.

You can read it this for yourselves, but let me just add one key quote.

The original angle perpetuated the idea that the growing number of ADHD diagnoses were somehow “scandalous” suggests to me that the producers’ minds were made up about ADHD long before they conducted this investigation

The investigation purports to hold these “exploitative” clinics to account, pointing to a high number of diagnoses. The show’s description says that a reporter has gone undercover as a patient at these clinics, to show that “diagnoses are being handed out to almost everyone who books an appointment”. As someone who was diagnosed by a private ADHD clinic – someone who scrimped and saved for months because I was let down by the NHS – this is nothing short of devastating..

Panorama has definitely failed in one of the foundations of journalism, that while holding those who deserve it to account, do no harm to the victimized community.

Shame.

March 31, 2023

It was “a dark and stormy night” in 1813

A dark and stormy night 1813 edition

(I don’t usually post excerpts from my work in progress, I often put far too much into first drafts and then have to drastically cut.

This episode of “a dark and stormy night” I discovered is too good to pass up. I am working on stories about my fourth great grandfather William Pennell, who was what today would be called a spy under diplomatic cover as British Consul in Bahia, Brazil, monitoring the South Atlantic slave trade. That meant he often had to liaise with Royal Navy captains, including Sir George Ralph Collier who was commodore of the West Africa Squadron, tasked with supressing that slave trade.)

Prior to that in the Napoleonic Peninsular War, Collier commanded a small squadron of ships providing operational support to the then Marquis of Wellesley (later Duke of Wellington) . Collier was in over command during on operation that took place one dark and stormy night in 1813.

On July 12, 1965, Snoopy, as penned by Charles M. Schulz, dragged a portable typewriter to his dog house and began to type a novel starting with “It was a dark and stormy night.

I had just turned 15 at the time and just received an Olivetti portable typewriter for my birthday. I am sure every kid who wanted to be a writer was up there with Snoopy, the typewriter and the doghouse when the Peanuts strip arrived in the newspapers (in the good old days when there were newspapers in every home) and “it was a dark and stormy night” became ubiquitous.

The best known use of “it’s a dark and stormy” night comes from the opening line Edward Bulwer Lytton’s 1839 novel Paul Clifford.

As Wikipedia says that line is considered an archetype of “purple prose”

It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents—except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.

Recent research has shown that American author Washington Irving used the phrase in his

1809 satirical book A History of New York. (It wasn’t in the opening line)

“It was a dark and stormy night when the good Antony arrived at the creek (sagely denominated Haerlem river) which separates the island of Manna-hata from the mainland.”

Two years later, in 1832, Edgar Allan Poe used it in “The Bargain Lost,” like this:

It was a dark and stormy night. The rain fell in cataracts; and drowsy citizens started, from dreams of the deluge, to gaze upon the boisterous sea, which foamed and bellowed for admittance into the proud towers and marble palaces.

Unlike Snoopy, Bulwer-Lytton, Irving and Poe, Sir George Ralph Collier was a naval officer, writing an official formal after action report that would appear in the London Gazette on November 9, 1813, beating Bulwer Lytton by seventeen years.

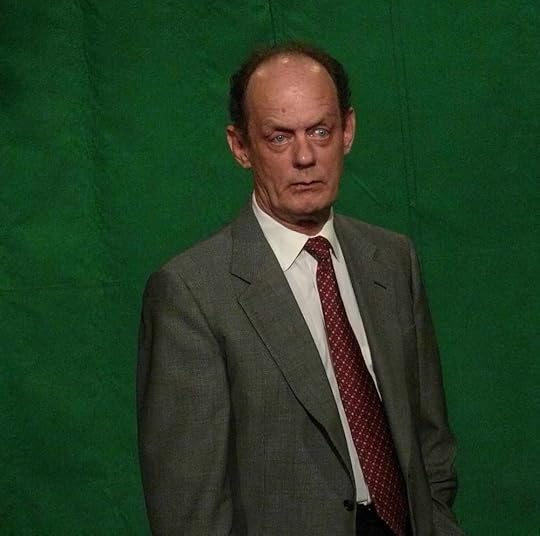

George Collier wearing a captain’s undress uniform of over three years seniority, 1812-25. He carries his sheathed sword in his right hand and points purposefully to the left of the picture with his left. He is portrayed standing on deck with a carronade to his right, and San Sebastian in Northern Spain in the background. (UK National Maritmie Museum via Wikipedia)

He described the action between the Royal Navy schooner HMS Telegraph and the French corvette Filibustier.

The Filibustier had been waiting an opportunity to seal out of St. Jean du Luz for some months past; the near approach of the Marquis of Wellesley army made it absolutely necessary, and a dark and stormy night1 determined her commander to risk the attempt.”2

In the summer of 1813, Arthur Wellesely, later the Duke of Wellington was attacking the Napoleon’s French forces and their allies along the north coast of Spain attempting to take the cities along the coast.

To simplify a complicated military situation for this blog, Collier’s small squadron was tasked with supporting the British forces with offshore support for the army and the Spanish guerillas and to help capture the strategic ports along the Bay of Biscay.

It was also the time of the war of 1812. Early in 1813, the Royal Navy captured an American privateer called the Vengeance and took the ship into the navy as HMS Telegraph. One of the swashbuckling young captains of the age, Timothy Scriven took command of the Telegraph in June 1813.

It was assigned to the Channel Fleet and operated mostly against American vessels.

On August 12, 1813, Telegraph chased for 44 hours and then captured the American schooner Ellen & Emelaine off Santander, Spain. On September 12, Telegraph captured four French vessels trying to reach Bordeaux. On September 22, Telegraph escorted a convoy from Plymouth to San Sebastian, bringing navy dispatches to Collier. Telegraph then joined Collier’s squadron. The British had recently captured San Sebastian after a siege and were using It as a base.

Wellesley meanwhile was preparing to cross the border and invade France.

The French still held the town of Santoña in Spain. Its garrison was holding out against a British siege. Capturing or neutralizing Santoña was crucial to protect Wellesley’s rear.

Across the Spanish border with France, the French held the fishing village of St. Jean du Luz, where the Filibustier and some smaller warships were based.

Watching St. Jean du Luz were HMS Telegraph, HMS Constant and HMS Challenger.

On October 13, Filibustier sailed from St. Jean du Luz, attempting to reach the nearby besieged garrison at Santoña. The escape attempt was, as Collier reported, “the approach of the Marquis of Wellesely’s army made it absolutely necessary, and a dark and stormy night1 determined her commander to risk the attempt.”

The Fillibustier was “carrying on board treasure, arms, ammunition and salt provisions and from her large compliment of men, probably some officers and soldiers for that garrison.”

The winds, however, carried the Fillibustier away from Spain toward Bayonne.

Before Filibustier could reach Bayonne it became becalmed at the mouth of the river Adour.

As night fell and the storm blew up again Telegraph spotted Filibustier and engaged, joined by Challenger and Constant.

Telegraph exchanged fire with the Filibustier for about three quarters of an hour. Either from the British cannons or perhaps deliberately set, Filibustier was on fire. The crew then abandoned the ship. Scriven sent his ship’s boats in an attempt to save the Filibustier and put out the fire.

That fire was so fierce, however, that the Telegraph’s boat crew had to abandon the ship after seizing the ship’s papers. The Filibustier then blew up. Lloyd’s List reported that there were 30 French wounded still on board, while Scriven reported “I have no means of ascertaining the enemy’s loss in killed and wounded, it must have been considerable, but I have the pleasure to state that the Telegraph did not lose a man.”

Collier also reported that the Filibustier was covered by the shore batteries at the mouth the Ardour and the encounter was “witnessed by some thousands of both armies.”

One wonders what other literary gems may lurk unnoticed in military dispatches

PS, Every year since 1982, writers have entered the

the Bulwer Lytton Fiction Contest that “has challenged participants to write an atrocious opening sentence to the worst novel never written.”

.

.

The Gazette, https://www.thegazette.co.uk/. No. 16803 November 9, 1813, p 2205

Lloyd’s List. No. 48920 November 9, 1813

September 11, 2022

Captain’s log 1819108

The UK National Archives at Kew, London

The UK National Archives at Kew, London

I’ve just completed five days of research for my Pennell Projects at the British National Archives at Kew. (And a couple of weeks earlier I spent the afternoon at the British Library in London).

I’ve just completed five days of research for my Pennell Projects at the British National Archives at Kew. (And a couple of weeks earlier I spent the afternoon at the British Library in London).

William Pennell was a diplomat and a spy under diplomatic cover from 1814 to 1832. That meant I had a lot of ground to cover and limited time to do it. The Foreign Office Archives contain most of his dispatches first from Bordeaux, a time when the British reestablished diplomatic relations with Bourbon France and then had to flee during Napoleon’s “One Hundred Days.” Pennell, with the cooperation of the Royal Navy had to coordinate the hurried evacuation of the British in the city.

Bound volume of William Pennell’s disptatches in the UK National Archives.

Bound volume of William Pennell’s disptatches in the UK National Archives.Pennell served as Consul in Bordeaux until 1817 when he transferred to Bahia, Brazil, where he carried out normal consular duties. His main assignment was to report intelligence on the South Atlantic slave trade to the Foreign Office and to also provide intelligence to visiting Royal Navy ships.

Pennell’s involvement with the Royal Navy meant that I aslo had to research the log books of the various ships involved in both the evacuation of Bordeau and the West Africa Squadron that was tasked to try to stop the South Atlantic slave trade. Bahia was the largest slave port in the Americas.

The captain’s log of HM Sloop Pheasant, 1819.

The captain’s log of HM Sloop Pheasant, 1819.The captain’s log of HM Sloop Pheasant, 1819. HMS Pheasant commanded by Commander B. Marwood Kelly, was one of the early ships assigned to the West Africa Squadron. While both Great Britain and the United States had outlawed the Atlantic slave trade in 1807, that law only applied north of the equator. Spain and Portugal (and other countries) were technically free to buy slaves and traffic them south of the equator. The main locations for the slave trade, however, were on the “Slave Coast” in the Bight of Benin and the Bight of Biafra, north of the equator. Intercepting the slave ships was the task of the underresourced West Africa Squadron.

In October, 1819, HMS Pheasant intercepted a Brazilian slave ship. Commander Kelly put a prize crew on board to take the slave ship to Freetown, Sierra Leone for court judgement. The prize never arrived and what happened to that slave ship, its prize crew, the slaves and the Brazilians is one of the stories I will tell in my book project.

The post Captain’s log 1819108 first appeared on Robin's Weir.

August 31, 2022

Topsham Devon, home of the seafaring Pennell family

The Topsham waterfront and docks on the River Exe. (Robin Rowland)

The Topsham waterfront and docks on the River Exe. (Robin Rowland) Topsham on the River Exe, in Devon, is the seaport for the larger city of Exeter. In the past week, I have had the chance to explore one of the towns where my roots are, the Pennells, on one main branch of my father’s side of the family.

Topsham on the River Exe, in Devon, is the seaport for the larger city of Exeter. In the past week, I have had the chance to explore one of the towns where my roots are, the Pennells, on one main branch of my father’s side of the family.

There were villages in the area of what is today Topsham going back at least to Celtic times and probably even earlier. The region was in the traditional territory of the Dumnonii which extended westward to the shores of the Atlantic in Cornwall. The Romans took over the larger settlement, calling it Isca Dumnoniorum, today Exeter, with a naval base farther down stream at Topsham, a point where the river is navigable by sea going vessels.

(When I was boy my favourite author was Rosemary Sutcliff, and her famous novel, Eagle of the Ninth, opens with a battle between the Romans and Celts at Isca Dumnoniorum, the settlement which in the story is on the frontier of Roman colonial authority. It wasn’t until years later that I found that I had ancestors who may have lived in Isca Dumnoniorum and one wonders if there is a distant epigenetic memory at work, because reading Eagle of the Ninth when I was nine or ten cemented both my decision to become a writer and my love for ancient history).

According to a biography of my second cousin 3 times removed, Theodore Leighton Pennell , the family likely settled in Topsham sometime in the early middle ages, and probably came from one of the towns in Cornwall with “Pen” as a suffix. Theodore Pennell was an Anglican medical missionary at the time to the British Raj, in what today is the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan. Today that is Taliban ruled country.

By the late Middle Ages, Topsham was a thriving port also known for ship building. (In later years two notable ships were built in Topsham, HMS Terror, part of the ill fated Franklin expedition to the Canadian Arctic and HMS Cyane/USS Cyane, which has a role in the books I am writing, both in the War of 1812 (where it tried to fight the USS Constitution) and anti-slaving operations.

The house that my guides told me belonged to Lovell Pennell in Topsham, Devon, in the mideighteenth century. (Robin Rowland)

The house that my guides told me belonged to Lovell Pennell in Topsham, Devon, in the mideighteenth century. (Robin Rowland)With records beginning in the early seventeenth century we find that William Pennell (1648-1702 my seventh great grandfather) was trading with the Virginia colony in 1691. His son William, (1688-1750 sixth great grandfather) made at least one voyage for the East India Company. His son Lovell Pennell (1719-1788, fifth great grandfather) was a captain of both merchant vessels and privateer. Lovell Pennell commanded three privateers, Exmouth, Exeter and Mediterranean. In Exeter, in 1745, he captured two prizes off Gibraltar, fought a battle with a Spanish galleon off Cape St. Vincent and then ran out of luck when the Exeter was captured by a French privateer.

It was prize money that allowed Lovell Pennell to invest in the civilian side of the extended family business. British goods were shipped from Topsham, to Porto in Portugal. There most of the ships would load salt from salt flats and sail to Trepassey in Newfoundland, where the salt used to produce salt cod. The ships then on the return journey would stop at either Waterford, Ireland or Topsham to sell the highly prized northern cod. (Some ships also would sail back to Topsham with Porto’s famous port wine)

Lovell’s son, William Charles Pennell (1765-1860, fifth great grandfather) is the most important Pennell character in my work. He began his career as the family manager and representative in Waterford. When the family business floundered during the Napoleonic War, he joined the British customs service. There he met another customs officer John Wilson Croker. Pennell’s daughter Rosamond married Croker, cementing their relationship. Croker went on to become one of the most prominent figures of early nineteenth century British history, as Secretary to the Admiralty at the height of the Napoleonic Wars, which meant every admiral and captain would address their letters to him. Croker was also a distinguished author and editor and a member of Parliament.

It is likely that Pennell gained intelligence experience in the customs service. In 1814, he was posted Bordeaux, France after the fall of Napoleon. But when Napoleon returned during the Hundred Days, it was up to Pennell to coordinate the emergency evacuation of the city in coordination with the Royal Navy. He returned to Bordeaux until 1817 when he was transferred to Bahia, where in addition to his regular consular duties, he was specifically directed by the Foreign Office to spy on the slave trade.

There are dozens more Pennells, from Topsham, from nearby Lime Regis and London who are fascinating historical characters from the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries.

My guides from the Topsham Museum told that throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the Topsham waterfront was an area for shipbuilding and other heavy industry. Today Topsham is a riverside town known for its nature reserves and bird sanctuaries. The Sunday Times named Topsham as one of the best places to live in Britain. (paywall)

For several days I walked around Topsham, visiting the museum, an ancient church, the restaurants and shops, streets that many of my ancestors walked. I walked along the tidal river where today there are yachts and small fishing boats, where once square rigged ships sailed down the River Exe and into the English Channel to the world.

It those ships that I will be writing about in my book projects.

Photo blogs from Topsham

Finding my roots in Topsham, Devon

The Bowling Green Nature Reserve, Topsham

Cormorants on the red Triassic cliffs of Devon

The post Topsham Devon, home of the seafaring Pennell family first appeared on Robin's Weir.

May 10, 2022

Two hunters from “Downton Abbey” came looking for bears in Kitimat, Kemano and the Kitlope in 1908

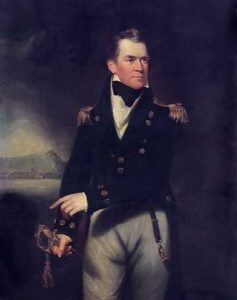

Masthead for Field in March 1908

In May, 1908, 114 years ago, two presumably rich, presumably British, hunters came to Kitamaat Village, hired two Haisla guides named “Frank” and “David” and went bear hunting in the Kitlope, Giltoyees and up the Kemano River.

One of the two hunters, named John H. Wrigley, would later write an account of his adventures which would appear in the British magazine Field The Country Gentleman’s Newspaper in March 1909.

That’s why I titled the story Downton Abbey, for the subtitle “Country Gentleman” and its many pages of ads for country estates certainly gives an indication of who the people were who subscribed to Field, 113 years ago.

Ad for a Scottish estate in the March 13, 1909 Field.

A couple of months ago there was a Facebook post about a gift “the Kitimaat Indians” had given to Queen Victoria in 1898. I am working on an unrelated research project and so I have a subscription to the British Newspaper Library archives . I wanted to see if I could find any more information about the “gift.”

The people from Kitimat and Kitamaat who responded were doubtful about its accuracy. What I found was that at least two dozen newspapers in Britain ran the same one paragraph story with no further confirming information. I had thought perhaps the gifts were presented to Queen Victoria on the occasion of her Jubilee in 1897 when people and towns and cities across the then British Empire were presenting gifts to the Queen. But these stories appeared much later in September 1898, which casts more doubt on that story.

What I did find was the two part series in Field about hunting in the Kitimat region that appeared in the on March 13 and March 20, 1909.

I have been unable, so far, to find out who the author, John H. Wrigley was. His byline doesn’t appear anywhere else in the database. There is internal evidence in the hunting article and one on fishing I will post later that he was British. (For example he uses the Scottish term “gillie” for fishing guides)

The Kitimat and Haisla readers will see how accurate the descriptions are of this region.

I have retained the original spelling of Kitimaat. Wrigley used Kitlobe which I have changed to Kitlope. The paragraphing has been changed for easier web viewing.

Both articles constitute a long read.

One note. The account was written in 1909 and reflects the attitudes of the time. It was an era when a British hunter in India could boast of killing two dozen tigers—tigers are now an endangered species.

The hunters in 1909 are not satisfied with taking one bear but several.

Today hunting black bear in BC is limited by licencing regulations, seasons and bag limits (and frowned upon by many people) and grizzly bear hunting is banned in BC. Wrigley, like his contemporaries believed that BC “It is a country that can never he shot out.” By using that phrase he must have known that there were already places that that had been ”shot out” including presumably Great Britain itself.

The best example is Wrigley’s description of how plentiful the oolichan were in1908 when he went up the Kemano River. Now the oolichan are now threatened or endangered.

FIELD, THE COUNTRY GENTLEMAN’S NEWSPAPER. Vol. 113.

Saturday 13 March 1909

SHOOTING. BEAR HUNTING IN BRITISH COLUMBIA I.

KITIMAAT, OUR LAST LINK WITH CIVILISATION — now an important Indian village, and a tempting location for the many land speculators who are following the construction of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway lies at the mouth of the Kitimaat Valley, where the wide river of the same rank drains into the sea.

Southward, northward, and westward are the interminable labyrinths of the Northern British Columbian fiords, wide sea-water channels of varying width, in most instances uncharted and absolutely unexplored.

For a thousand miles this western seaboard of Canada, from Puget Sound up to the much-debated Portland Canal, is scored by innumerable inlets. studded by an amazing archipelago of islands of all mixes and seamed in every direction by the intricate waterways referred to.

Our route took us up the wild and desolate Gardener Canal, two hundred miles off the beaten track of the coasting steamers on the Alaskan run—a weird, forbidding country, but seldom visited by any white man, save the wandering timber cruiser or mining man; a country of stupendous mountains rising sheer from the sea, with half a dozen isolated valleys draining a vast extent of the unexplored ranges of the The extreme inaccessibility of this portion of British Columbia has no doubt much to do with the numbers of both black and grizzly bears that are still to be found there.

It is a country that can never he shot out.

For six months in the year these densely timbered mountains amongst which the bears live are for all intents and purposes impenetrable; then for a few weeks an occasional chance may be obtained, when the animals forsake the forest uplands for their coveted diet of salmon from the overcrowded streams, and then away they go some hole or corner in the rocks, where they drowse away the winter.

With the advent of spring. however, there is a short, indefinite season of a few weeks’ duration, best defined as the period between the departure of the snow from the low ground and the hasty growth of foliage on the cotton-wood brush, when the bears forsake their dens, still fat and ravenously hungry, to feed on the open ravines and hillsides, bared of cover by the avalanches of former years.

Here the bears find a sparse growth of vegetation in the sheltered corners, which forms their diet.

As the spring comes but slowly and the sun has but little power, save for an hour or so at noonday, this vegetation is but scanty, affording only a semblance of a meal to the overpowering appetites of the hungry animals. This forms one of the chief difficulties of the stalker, for his quarry is constantly on the move hunting for grass.

We picked up our Iwo Indians at Kitimaat, Frank and David, two of the best hunters in the tribe of Kitimaats, who bad been with us the previous season. Such eyesight as these men possessed was little less than marvelous; the ease with which they could distinguish the black outline of a bear against a far distant hillside bordered on the miraculous, and it was only to determine the nature of the animal they had spied—grizzly or black bear—that the services of a spyglass were requisitioned.

From Kitimaat to our destination at the head of the inlet, a distance of two hundred miles, we were lucky enough to obtain a welcome lift in Lieut.-Governor Dunsmuir’s big tugboat Pilot, which we found awaiting us at the wharf.

This great convenience saved us many days of arduous canoe work, for Gardner Inlet is notoriously storm-tossed, and devoid of sheltered anchorages to an alarming extent. We steamed all day up the successive reaches of this wild, forbidding expanse of landlocked water. with great mountains rearing their gaunt, snow-clad sides sheer front the water’s edge.

We took Frank’s big canoe slung in the davits, for it was upon this craft we proposed to spend the whole of our time after the Pilot left us.

Arrived at the head of the inlet, we found the conditions even more wintry than they had been nearer the tidal influences of the Pacific, and after a consultation with the Indians we reluctantly had to confess that our chances, for fourteen days at least. seemed to be very problematical.

We anchored that night off the mouth of the Kitlope River in the midst of a snowstorm that obliterated every landmark. The only sign of human habitations passed during the day had been the empty houses of the considerable Indian settlement at Kemano, a village picturesquely situated on a pine-clothed sandbar at the mouth of the Kemano River. twenty miles from Kitlope, at the head of the inlet., and eight or nine hours’ steaming from Kitimaat.

The place was entirely deserted by the Indians at this season of the year, owing to their annual harvest of a small fish known as the oolichan, or candle-fish, an oily, flabby, smelt in appearance, deemed a delicacy by a British Columbians and coveted beyond all else by those fortunate tribes of Coast Indians who have an oolichan river in their vicinity.

This fish runs up all the Gardner Inlet streams during May in numbers too great to permit of even a hazy estimate; as the tide recedes countless millions are left stranded on every sandbar, a bounteous feast for noisy, querulous gulls, crows, divers, and eagles.

This amazing waste of fish life became very obvious to our olfactory nerves as we approached the mouth of the Kitlope River next morning, determined to pole up a dozen miles to the Kitlope Lake to ascertain whether the country farther inland was yet clear of snow and huntable.

It took us nearly four hours to reach the temporary camp of the Kemano Indians, some three miles up stream, where we found the whale tribe of the Kemanos busily boiling down tons of oolichan in rough cedar-wood vats constructed on the banks of the et am. Two of the tribe had only returned from the lake that morning, and reported it still frozen over and hunting out of the question, but we decided to go and judge for ourselves.

For a mile or so below the lake the river becomes exceedingly narrow and turbulent, necessitating continual use of the tow rope, in addition to strenuous work with the poles. At last, after one final struggle over the rapids that surge round the outlet, we paddled smoothly on to the still waters of this truly magnificent sheet of water, only to find that we had been told the truth, and that the bear country in the vicinity was still covered with snow.

We therefore lost no time in changing our plans, glided down stream in as many minutes as it, had taken us hours to get tip, and were soon on board the Pilot, bound for Kemano and the subsidiary valleys thirty miles lower down the main inlet.

The Pilot left us at Kemano next morning and proceeded on her five-hundred mile run to Victoria, so we cached certain amount of stores in one of the empty houses at the village and loaded up the canoe with sufficient to last us for a forthright.

Then we hoisted the big spirit sail and ran down some half-dozen miles to a group of bare “slides” and open country known to our guides as likely bear ground.

The glasses were hardly out of their case when I heard the two men excitedly whispering to each other: ‘There he is! there he is!” Sure enough. we soon bad the glasses focused on a black bear grubbing amongst the rocks 500 ft. or above the water.

Having won the toes for first stalk, Frank was not long in shoving me ashore in the canoe.

We had an awesome climb, for the first 300 feet or 400 feet consisted of a sheer rock wall that overhung the water with only a narrow cleft. along which we gingerly picked our way upwards until we were well above the bear. We crept cautiously down to where we had last seen him feeding, and then he must have winded us at the same instant we saw him, for in the twinkling, of an eye he had whipped over a fallen log, and we heard the stones flying as he raced out of sight downhill.

There was just a possibility we might obtain a second chance at him as he crossed a steep, rocky ravine a hundred yards below us, and. sure enough, he slow walked into view, obviously out of breath and very much scared, at less than the distance we had estimated. The first shot flicked up the pebbles beneath his hind legs, which caused such an involuntary leap out his part that even Frank’s lethargic features relaxed into the semblance of a smile. The bear then scrambled along the opposite side of the ravine, feeing us, every now end then stopping to lower his twinkling back eyes in our direction while we prepared for a second shot. Momentarily he paused and the Mannlicher sights were levelled steadily against the white star on his chest. At, the shot he rolled over and over downhill until he fetched up against one of the many boulders choking the bottom of the ravine.

Wo were now beside him and found him to be a fine male in superb e – at. and obviously only a few days out of his den. A bear skin in May is a vary different trophy from the dilapidated specimens obtained late in the summer or the early autumn.

This beast was literally rolling in fat, in spite of the fact that beyond a handful of uninviting grass his body contained no signs of other food.

We soon had him skinned, and packed his skull complete, downhill to the canoe.

For two days we hunted the many excellent slides in the vicinity of the Brin River Valley, one of the principal subsidiary valleys that drain into Gardner Canal; but the wintry conditions that still prevailed proved prejudicial to our chances, and we passed much excellent bear country that would not otherwise have proved blank.

From our camp at Brin River, we hunted the slides to the northward without success until the evening of May 5, when David spied a fine black bear high up on the face of the mountain above us, feeding restlessly from the successive couloirs, where faint traces of greenery offered the possibility of a meal.

We had a good look at him through the telescope. He was a much heavier bear than our first one, and, like his predecessor, in perfect coat. He was, as David told us, very restless, for in between the mouthfuls of grass he snatched from each little bench or gully he literally ran on to find his next mouthful. He was fully half a mile uphill above us, close under a sheer rock wall that fell precipitously from the glaciers and infields above, the ground between us, though steep in all conscience, being fairly open, and covered with strips of burnt and fallen timber.

The rock wall, the home of ravens and eagles, was topped by miles upon miles of snow. We waited until the animal fed down wind behind a corner of the rock wall, and then away we went after him. It was a matter of small difficulty picking up his tracks and following cautiously along them, for everywhere he bad left very evident traces of his overpowering hunger—great tussocks pulled up bodily and hurled on one side as unsavoury.

Frank now advanced with even greater caution, and peering over a boulder in front of us, we saw our bear grubbing away at the roots of scone cotton-wood bushes, his body half hidden by the stem of a withered tree. Then lie moved his shoulder into full view, and a second later it was pierced by a Mannlicher bullet. No one could mistake the thud that was heard, although he galloped away downhill with apparent strength and speed, when suddenly he collapsed and fell head foremost into a dense patch of cotton-wood brush. He proved to be a. very big bear, two feet. longer than our first one, and again we found it impossible to exaggerate the excellence of his coat—black, deep, and glassy, with no trace of any worn patches.

John H Wrigley

A page of ads for guns in the March 13 1909 issue of Field

FIELD, THE COUNTRY GENTLEMAN’S NEWSPAPER. Vol. 113.

Saturday 20 March 1909

BEAR HUNTING IN BRITISH COLURBIA.–II.

FROM THE BRIN RIVER VALLEY we moved on, with a favourable slant in the wind, to a very beautiful inlet on the western side, unmarked in the latest Admiralty charts, but known to the Indiana as the Inlet of Gilt-to-yeas.

Here we found slides extending over a mile of country, a well-known haunt for bears at this season of the year, but still covered with snow, with green strips of grass along the edges of the ravines.

We left camp early in the afternoon of our arrival at this glorious land-locked inlet, in plenty of time for a good spy and au evening stalk, nor had we to wait more than half an hour under the shadow of the trees on the side facing the bear ground before a large black bear stepped into the sunlight on a knoll 500 ft. above the water. He was three-quarters of a mile away when we first saw him and looked immense. We watched him walk down to a narrow torrent of snow broth, where he drank eagerly, and then we sent the canoe flying across the inlet as fast as four pairs of arms could make her go.

Directly her keel grated on the rocks we were ashore and off uphill after him. The wind had died away, and it became intensely still. At last, we stood on the plateau, within fifty yards of where we had last seen our bear, and, glancing downwards to the canoe, could see an oar held vertically in the direction of camp, telling us that our bear was ahead of and above us, though still invisible to us. With rifle at the ready we cautiously approached the clump of trees indicated, and were actually within fifteen yards of the beast, when with an angry cough he was gone.

Regrets were useless; we rushed to the highest point near in and could follow his track through the brush by the swaying of the branches. but he never gave us the slightest chance of a shot. We spent several days at Gilt-to-yees, but owing to the mild weather our chances were ruined by the thunder of continual avalanches, keeping game on the move and bears in the recesses of the forest. Day and night one beard a continuous roar as thousands of tons of snow fell ceaselessly in all directions.

From Gilt-tu-yen we moved back thirty miles to Kitlope, at the head of Gardner Inlet proper, in the hope that the fortnight’s interval might have brought fairer weather.

We took up our abode in a deserted Indian hut at the mouth of the Kitlope River. On the afternoon of our arrival, we separated for the evening hunt, my companion watching some excellent slides at the junction of the Kitlope and an unnamed river that evidently drains the country to the northward and eastward of the Kitlope, while I took the Indians and the canoe to watch all the country for a mile down the west aide of the inlet.

We were soon afloat and had not rowed a furlong before the men sighted a bear on some narrow slides about a mile away. He was feeding close to the water, so we had to use the utmost caution.

As we came nearer, he would stop feeding occasionally, looking anxiously in our direction, and, though a bear’s eyesight is his weakest point, we rested on our oars until he again set to work munching great mouthfuls of grass from the openings among the trees.

What little wind there was favoured us, and we were soon ashore, immediately below the strip of covert in which he was feeding. The avalanches in this particular section of the mountains had cut the forest into consecutive strips of covert, leaving regular rides between each section, just as clean cut, and bare of timber or undergrowth as the rides in any English game covert.

Frank noiselessly stole up the slide where the bear bad last been feeding in case he broke back, David and I taking the next one where we imagined ho might next emerge.

Five minutes, ten, twenty passed. A twig cracked, and out he came into the sunlight less than forty yards away, a glorious spectacle of a wild animal at home. He never saw us, as we crouched beside a log.

The sun shone straight into his eyes and appeared to daze him, so I drew a bead on his broad shoulder and let him have it. It was the easiest chance imaginable, and no duffer could have failed to take advantage of it. This, our third bear, had a coat every bit as fine as his predecessors, and in size ranked a little smaller than our second.

Rowing home in the twilight we watched a Kemano Indian stalking a small brown bear on the hill above us and were greatly interested to see the stalk end in the discomfiture of the Indian and the bear galloping a mile away over the distant snowfields.

We hunted in the vicinity of the mouth of the Kitlope River for at least ten days, and saw during that time at least a dozen bears, some of which doubtless were seen twice over.

With the Kitimaat and Kemano Indians May 14 is deemed the first day of bear shooting from the fact that the average spring is so timed that the date in question is accepted as approximate. Our fourth bear came to hand after many unsuccessful stalks in the Kitlope country.

We camped at the mouth of the Brin River, twenty-five miles from Kitlope, and were watching some slides in the vicinity, when, half a mile away, a big black bear suddenly scrambled to the top of a withered pine tree in full view of the canoe.

We were at a loss to account for this extraordinary behaviour when she lowered herself down again, and we went after her. The hillside at this point proved to be very precipitous, choked with fallen timber and dense underbrush , so thick that little or nothing could be seen until we climbed up a few hundred feet on to the rocky plateau where we had first seen the bear, when we paused for breath.

Below us lay the canoe containing our companions; above us a steep but narrow cleft in the rock showed us the stunted tree the bear had so recently climbed, and we crawled upwards beside a small cascade among the rocks to a point that seemed to cover the place where the bear lay feeding.

Quietly we crawled up and peered over. She must have looked up almost at the same instant, for our first shot, fired as she galloped away up the narrow cleft in the rocks, splintered the rocks ten yards ahead of her.

She turned slightly at the second bullet, lost her balance on the slimy boulders, and the next moment came tumbling bead over heels to the edge of a steep bluff, over which she fell 50ft. on to a ledge of jagged rocks below. Here she feebly tried to regain her foothold without success, and when we reached her after her second fall she was entangled in the bushes, stone dead.

Meanwhile, our voices were drowned by overwhelming cries from a small cub. This little creature we easily caught, and subsequently regaled with a mixture of condensed milk and sugar. It is now the pet of the children in the park of Vancouver City.

May 28 proved to be the red-letter day of our trip. We left our camp at Brat River at. four in the morning and had not travelled a mile before we spied a heavy black bear on the east side of the inlet, feeding amidst thick cottonwood brush within a hundred yards of the water.

Prom our point of view he could not have chosen a better position. The wind blew steadily in our faces; above where he was feeding impassable crags towered away up to snow line; down wind his retreat was cut off by a precipice, and when we had hastily blocked his only outlet on the up- wind side we realized he was bound to afford a shot.

It was, however, a dangerous maneuver to give him our wind before the canoe reached shore, but we were ready directly the keel grounded, and were up the hill before the bear realized his awkward predicament. He was probably only just out of his winter quarters, for he sulked in the bushes out of sight. I motioned Frank to stir him up, and waited by the trunk of a dead tree, where a narrow game trail led through the brush in his direction. Prom this position I moved forward to a point where the game trail crossed a narrow cleft in the steep hillside, offering perhaps fifteen or twenty yards’ clear view ahead.

Through the tops of the pine trees on the left. one could see the silvery glimmer of the sea below, and on the right the vast, precipitous rock wall towered upwards into the clear blue sky.

Every sense was naturally on the alert at the proximity of the bear, but the denouement was certainly unexpected. I heard Prank’s excited yell from above me : “Look out, below them!” There was only one possible way to look, and that was along the game trail, but I certainly never expected to see that great brute suddenly appear on the very path on which I myself was standing, lees than fifteen yards away.

If he had not received a bullet in his great chest almost the instant be appeared in sight he would have undoubtedly pushed me off the trail. At the shot he fell sideways downhill and a second shot through the neck effectually settled him.

This was the largest black bear killed up Gardner Inlet last season, a very fine male in perfect coat.

Even the Indians, who speak of a skin with the critical eyes of the fur trader, view obliged to confess this great bear was one of the best. they had ever seen. It took three of as to lift him out of the wedge into which he had Wien sad pall him downhill towards the canoe.

We had now heavy bears on board, the female of the previous night and the one just killed, so we hoisted the spritsail and made short tracks to a length of sandy beach, where the warm sun offered a congenial point for the operation of skinning.

At this particular point. Gardner Inlet takes a complete rectangular bend, its course changing from a direct N.E. by E. to ono in an alitio.t contrary direction.

This huge bend forms a sheltered bay on the eastern side, where the sun had evidently melted the snow earlier than usual, and the resulting avalanches haul left a succession of bare slides stretching from the water’s edge for a mile up to the snow line.

Every inch of this grand country needed careful spying, nor were we long in finding what we were in search of. David, whose keen eyes were glued to the rock walls immediately below the snow, was the first to sight him, a great brown fellow, though whether a grizzly or not we were unable to determine at the distance.

The country was more or less open, with here and there clumps of stunted trees in the centre of glades devoid of underbrush, while the wind-swept slides were completely bare of cover.

My companion and his guide were soon away uphill after this bear, and for a time we lost sight of the two men amidst a thicket of cottonwoods.

When we next saw them, they were- within a hundred yards of the unsuspecting bear, and we could see the glimmer of the rifle barrel in the sun.

With the report of the shots the bear galloped away but had not run a hundred yards before he rolled over among the rocks, and we soon scrambled up to him.

He proved to be a remarkably fine brown or cinnamon bear, only a few inches shorter than our last black one, with a coat of almost chestnut hue, thick and glory.

My companion, who has probably killed more bears than any other non-professional hunter in British Columbia, was justly proud of the beast.

We had now three bears to engage our attention for the next few hours, and while three of us set to work skinning David prepared a savoury meal.

It took us until three in the afternoon to clean and stretch the skins, when suddenly Frank exclaimed, Look there!” We all sprang to our feet and followed the direction of his outstretched hand.

There, less than half a mile uphill, fast asleep on a huge, isolated boulder, lay a great black bear. Incredible though it may seem, we had for more than two hours cooked our food, laughed, talked, and smoked our pipes while that bear had walked up and gone to sleep practically within rifle shot. With his head resting on hiss outstretched forepaws, he was evidently oblivious of our proximity.

From where we stood the bare hillside stretched upwards to the snow line fully a mile away, and ho lay on a boulder about halfway up the slope. Frank and I had merely to change our boots for rubber-soled shoes, throw off our coats, and away up the centre of a narrow cleft filled with muddy, melting snow.

Beneath this crust of snow, a noisy little stream dashed downwards in a series of waterfalls to the sea below, effectually drowning any noise from our footsteps, affording us a grand approach to within a hundred yards of the bear.

The wind was just right, and an easier stalk could hardly be imagined. Then we climbed up 10feet. to the lip of the gully, raised our beads cautiously, to find ourselves within fifty yards of the still sleeping animal.

One bad but to raise the rifle to a convenient position, push up the safety catch, and draw a fatal bead on his shoulder.

At the shot he fell or rolled off the rock in one frenzied dive into the thicket below, and though he wormed his way for half a mile before Frank finally gave him the coup de grace, he was obviously ours from the first.

It turned out subsequently that the first bullet, aimed for his shoulder as he lay outstretched, had struck him too low, and was within an ace of inflicting a trivial wound that would have lost him to us for ever.

Our luck for the day was now about finished, for though we sighted yet another bear on the east side just before sundown, he was too high up, and it was too dark, too late, and too dangerous to go after him.

We cruised down the Inlet for another fortnight, and saw bears in several of the subsidiary valleys, but with our great day at the Brin River our adventures were practically at an end.

We were detained by contrary winds and bad weather for another week before reaching the nearest settlement, when a south-bound steamer might be expected, and two idle days had to be wasted before a steamer of any kind came along and bore us southwards.

Looking back at the results of that trip and the number of bears seen, I am more than ever convinced of the necessity of being on the spot as early in the spring as possible, for once the leaves cover the cottonwood bushes the bears are lost in a veritable jungle.

John H Wrigley

May 2022 cover of The Field

Astonishingly The Field (no longer Field The Country Gentleman’s Newspaper) is still in existence when the digital carnage has lead to the deaths of many magazines and too many newspapers. Field was founded as a weekly in 1853 and is older than any other currently monthly British publication. It is the world’s oldest rural affairs magazine. Only one British magazine is older, the weekly The Economist (founded 1843). The Observer (founded 1791)is now the Sunday newspaper version of The Guardian.

In a later post, I will reprint Wrigley’s recommendations for fishing in British Columbia in 1908.

1909 fishing tackle adf

February 17, 2022

The Ottawa protestors are partying on the 80th anniversary of a real crime against humanity the sook ching massacre in Singapore.

(Warning: This post may be triggering to people or their families who were victims of real crimes against humanity. I didn’t want to raise the temperature of the Ottawa protest debate but the continuation of the blockades and remembering the anniversary date compelled me to write this).

The heads of Chinese men on poles after the sook ching massacre in Singapore. Sketch by Leo Rawlings.

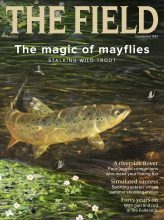

The so-called freedom convoy protestors on the streets of Ottawa who are barbecuing pigs on spits and lounging in hot tubs, playing in a bouncy castle, claiming that getting a vaccine or wearing a mask in a pandemic is a crime against humanity have no idea that this the 80th anniversary of a real war crime.

On February 14, 1942, in the Second World War, Singapore surrendered to the Imperial Japanese Army. Thousands of British, Australian and Indian Army soldiers became prisoners of war, including my father, who was a British artillery officer. They marched into captivity as prisoners of war. That story is somewhat well known because of books and movies.

What is less known, unless you are a resident of Singapore, or, like me, from the family of a POW, that beginning a couple of days after the surrender, the Imperial Japanese Army began rounding up ethnic Chinese men and boys across the island city.

This roundup came to known as the Sook Ching (肃清) or “the cleansing.” The most reliable accounts show that over the next few days, 50,000 men and boys were massacred by the Kempeitai, the Japanese military secret police. Most of them lined up and shot with machine guns.

Evidence introduced at post war crimes trials showed that this real crime against humanity was planned well in advance of the invasion of what was then the British colony of Malaya.

Each year, including this year, Singapore marks the anniversary of the massacre.

After the IJA occupied the city, the ethnic Chinese men and boys were ordered to report for “registration.” Then they were put into trucks and taken to points around the city to be shot.

In 1962, the Singapore authorities found five mass graves at just one massacre site, Siglap. More have been found since that discovery.

Even in 2022, just as indigenous people in Canada are searching for unmarked graves from residential schools, there are still ongoing searches for graves across Singapore using ground penetrating radar.

So the reader can understand why I have total and utter contempt for any protestor that claims that doing the right thing, getting a safe and effective vaccine to protect themselves and others, that wearing a mask to protect their community constitutes a crime against humanity.

Watching Question Period over the past week or so, I also want to express my total disgust at the braying members of the Conservative Party of Canada, playing politics, giving aid and comfort and support to an unruly mob who have no respect for science and medicine; some of whom came to Ottawa with the fantasy of trying to overthrow a democratically elected government and replace it with a self appointed junta.

My contempt for this movement began just as the first trucks arrived in Ottawa on January 28.

Earlier in the month I had reported a story for Northern Beat online newsmagazine about the high vaccination rate in Kitimat where I live. Kitimat Vaxxed to the Max

On January 29, I was then told that a one time candidate for the Peoples Party of Canada was threatening to sue over the article (even though that there is absolutely no legal basis for that). The email also said he planned a lawsuit against (BC health officer) Bonnie Henry and (BC minister of health) Adrian Dix for their ‘crimes against humanity.’ This (like those protestors who cite the Nuremberg trials of German war criminals) has absolutely no basis in international humanitarian law. (I have an interdisciplinary Masters Degree war crimes studies in history and law from York University and Osgoode Hall Law School). This a dangerous fantasy.

My father as a 21-year-old British lieutenant.

That trigger moment made me sick, given what I know about Japanese war crimes and the victims, including my late father.

My father was one of the 61,806 Allied prisoners of war sent to work as slave labour on the Burma Thailand Railway of Death. Evidence showed that 35,756 POWs died. Again many people will be aware of these crimes against humanity from movies and books.

What is a lot less well known is the fate of the romusha, a word translated as “coolie” and really meant slave. The Japanese forcibly recruited men, women and children from what was then Burma (now Myanmar) for what they called a “Sweat Army.” Official estimates indicate at least 166,000 what today would be called people of colour were sent as forced labour on the railway. Unlike the military which kept records, it is not known how many of these people died from the forced labour, starvation and from the largely forgotten 1943 cholera epidemic that spread across India and Southeast Asia during the war time conditions. The official estimate by war crimes investigators was that the number of deaths was in the tens of thousands. (although that is hard to confirm because a few of the romusha were able to desert and return home. )

When I watch the privileged protestors barbecuing on Wellington Street, I remembered that when my father was freed from the infamous prisoner of war camp at Changi Jail, he weighed just 83 pounds. Do we see any six foot two protestors in Ottawa that are just 83 pounds?

The health effects of imprisonment and slave labour lasted his entire life. He had suffered not only from

Ronald Searle’s sketch of a prisoner of war suffering from cholera on the Burma Thailand Railway in 1943.

cholera, but dysentery, malaria, the vitamin deficiency disease beri beri and jungle ulcers. I first found out about jungle ulcers when I was about five when, given my height, I noticed a ugly white scar on his thigh. Jungle ulcers occurred when a person experiencing starvation or other stress, suffers a cut or abrasion. With the immune system weakened, a bacterial infection eats away at the muscles and flesh of a limb, usually the lower leg, often decaying the flesh to the bone or even infecting the bone itself.

And people think that wearing a mask is a violation of their personal freedom?

All surviving Allied prisoners of war, who returned to the relatively privileged life in the western world, suffered both physical damage and psychological trauma for the rest of their lives. Only few ever received proper medical and psychiatric treatment for their suffering. Of course, the Burmese romusha and others enslaved across the Japanese Empire did not get any treatment.

There are indications that people who are suffering what is called “long covid” could, unless there is a medical breakthrough, have to deal with those symptoms for the rest of their lives.

To return to the sook ching, I will conclude with an passage from my book The Sonkrai Tribunal A River Kwai Story where the Allied POWs at Changi Jail witnessed the massacre and worked help some escape.

On Friday February 20, some men…were loaded into three trucks at a local school. At first they thought they were being taken to Changi gaol but the trucks passed by the walls of the prison, and then Serlang Barracks. British prisoners of war watched the trucks passing. The trucks stooped at a collection of huts called Changi Village. There the men were robbed of rings, watches, wallets and cash and marched to Changi Beach…Lying prone in the brush was a squad of Japanese soldiers with machine guns and a bren gun in the middle. They opened fire, continuing as bodies piled up on the beach…

Around dusk, a Malay fisherman approached the British and told them there were survivors. A doctor and two orderlies went to the beach but found no one alive. The next morning, a corporal found one wounded man. He was taken back to the camp and secretly to a military hospital.

A Japanese officer ordered some British prisoners of war to the beach and sat under a palm tree and watched as the prisoners dug shallow graves. Out of sight of the guards, a British medical officer searched the knee high Lalang grass and brush and found four more wounded men, who were covertly taken to hospital.

When British officers complained to the Japanese about the shootings they had witnessed the reply was “These Chinese are bad men. That is why we shot them. Have you anything more to ask?”

There have already been loud objections to those protestors against vaccine mandates, in Ottawa and elsewhere, that have appropriated the yellow star the Nazis forced the Jews in Europe to wear.

As Atlantic Magazine columnist David Frum tweeted this morning.

The protestors are demanding for freedom for themselves and no one else. They want freedom of expression but do not want freedom of the press. They want freedom without any responsibility. They are prime examples of George Santayana’s idea that “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

For three weeks the Ottawa protestors have denied freedom to the residents of the city, harassed and threatened those residents. Hundreds of people in Ottawa are demanding the end to what is in effect a hostage taking. As for the “marginalized” truckers, the price of the big tractor trailers in the protest according what they themselves have told reporters is $155,000. Anyone who owns a large RV or a heavy duty pickup is not struggling working class. The hundreds of minimum wage employees at the Rideau mall and other small stores that have been forced to close the last three weeks by the protest (not health orders) are the real struggling working class.

While some politicians and commentators rightly worry about the justified imposition of Canada’s Emergencies Act, the same politicians ignore the far more dangerous long term implications the continuing war on science and medicine by mostly conservative politicians around the world.

Equally dangerous is the idea that medical treatment to help end a world wide pandemic is some how a crime, that personal and religious freedom outweigh the lives of the millions of people who have died from Covid-19, the millions more who have been made ill by the virus and those living with long Covid.

The question we’re not hearing from the Conservatives in Question Period and the outraged commentators is what happens when the next pandemic inevitably hits the planet? Why are they not denouncing the idea that wearing a mask is a crime against humanity?

More on my book A River Kwai Story: The Sonkrai Tribunal

The deluded post from the anti-vaccine protestors about crimes against humanity expressing their hatred of the media.

October 17, 2020

“A point far off in imaginary space.” In 1970, two books tried to predict 2020. How right were they?

Fifty years ago, in 1970, two books, one published in the United States, the second in Canada, both gathered prominent writers to predict what the year 2020 would be like. As one might expect, no one got it entirely right. There were hints of things to come.

Fifty years ago, in 1970, two books, one published in the United States, the second in Canada, both gathered prominent writers to predict what the year 2020 would be like. As one might expect, no one got it entirely right. There were hints of things to come.

Now it’s 2020. The world is facing the unexpected. A worldwide pandemic that has, of Oct. 16, sickened 39.3 million and killed 1.1 million world wide; sickened 8.09 million in the US and killed 218,000; sickened 194,000 and killed 9,722 in Canada.

The west coast of the United States is still on fire. Earlier in 2020, in its summer Australia was also on fire. As fires rage in the United States the Amazon rainforest and the wetland of the Pantanal are also burning. causing a disaster of the local environment