Iain C. Martin's Blog, page 2

June 17, 2013

James Fremantle Meets President Jefferson Davis, June 17, 1863

Continuing our countdown towards Gettysburg's 150th anniversary we find Arthur Fremantle arriving in Richmond on this day in 1863 where he meets with Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin who introduces him to President Jefferson Davis:

17th June, Wednesday.--We reached Petersburg at 3 A. M., and had to get out and traverse this town in carts, after which we had to lie down in the road until some other cars were opened. We left Petersburg at 5 A. M. and arrived at Richmond at 7 A. M., having taken forty-one hours coming from Charleston.

The scenery near Richmond is very pretty, and rather English-looking. The view of the James river from the railway bridge is quite beautiful, though the water is rather low at present. The weather was extremely hot and oppressive, and, for the first time since I left Havana, I really suffered from the heat.

Richmond, VA taken in 1862

Richmond, VA taken in 1862

I kept my appointment with Mr. Benjamin at 7 o'clock. He is a stout dapper little man, evidently of Hebrew extraction, and of undoubted talent. He is a Louisianian, and was Senator for that State in the old United States Congress, and I believe he is accounted a very clever lawyer and a brilliant orator. He told me that he had filled the onerous post of Secretary of War during the first seven months of the secession, and I can easily believe that he found it no sinecure. We conversed for a long time about the origin of Secession, which he indignantly denied was brought about, as the Yankees assert, by the interested machinations of individuals. He declared that, for the last ten years, the Southern statesmen had openly stated in Congress what would take place; but the Northerners never would believe they were in earnest, and had often replied by the taunt, "The South was so bound to, and dependent on the North, that she couldn't be kicked out of the Union."

Judah P. Benjamin

Judah P. Benjamin

He asserted that England had still, and always had had it in her power to terminate the war by recognition, and by making a commercial treaty with the South; and he denied that the Yankees really would dare to go to war with Great Britain for doing so, however much they might swagger about it; he said that recognition would not increase the Yankee hatred of England, for this, whether just or unjust, was already as intense as it could possibly be....

He said the Confederates were more amused than annoyed at the term "rebel," which was so constantly applied to them; but he only wished mildly to remark, that in order to be a "rebel," a person must rebel against some one who has a right to govern him; and he thought it would be very difficult to discover such a right as existing in the Northern over the Southern States.

In order to prepare a treaty of peace, he said, "It would only be necessary to write on a blank sheet of paper the words 'self-government.' Let the Yankees-accord that, and they might fill up the paper in any manner they chose. We don't want any State that doesn't want us; but we only wish that each State should decide fairly upon its own destiny. All we are struggling for is to be let alone."

At 8 P. M. Mr. Benjamin walked with me to the President's dwelling, which is a private house at the other end of the town. I had tea there, and uncommonly good tea, too--the first I had tasted in the Confederacy...

President Jefferson Davis

President Jefferson Davis

Mr. Jefferson Davis struck me as looking older than I expected. He is only fifty-six, but his face is emaciated, and much wrinkled. He is nearly six feet high, but is extremely thin, and stoops a little. His features are good, especially his eye, which is very bright, and full of life and humor. I was afterwards told he had lost the sight of his left eye from a recent illness. He wore a linen coat and gray trousers, and he looked what he evidently is, a well-bred gentleman. Nothing can exceed the charm of his manner, which is simple, easy, and most fascinating.

He conversed with me for a long time, and agreed with Benjamin that the Yankees did not really intend to go to war with England if she recognized the South; and he said that, when the inevitable smash came--and that separation was an accomplished fact--the State of Maine would probably try to join Canada, as most of the intelligent people in that State have a horror of being "under the thumb of Massachusetts." He added, that Maine was inhabited by a hardy, thrifty, seafaring population, with different ideas to the people in the other New England States. When I spoke to him of the wretched scenes I had witnessed in his own State (Mississippi), and of the miserable, almost desperate situation in which I had found so many unfortunate women, who had been left behind by their male relations; and when I alluded in admiration to the quiet, calm, uncomplaining manner in which they bore their sufferings and their grief, he said, with much feeling, that he always considered silent despair the most painful description of misery to witness, in the same way that he thought mute insanity was the most awful form of madness.

When I took my leave about 9 o'clock, the President asked me to call upon him again. I don't think it is possible for any one to have an interview with him without going away most favorably impressed by his agreeable, unassuming manners, and by the charm of his conversation. While walking home, Mr. Benjamin told me that Mr. Davis's military instincts still predominate, and that his eager wish was to have joined the army instead of being elected President.

During my travels, many people have remarked to me that Jefferson Davis seems in a peculiar manner adapted for his office. His military education at West Point rendered him intimately acquainted with the higher officers of the army; and his post of Secretary of War under the old government brought officers of all ranks under his immediate personal knowledge and supervision. No man could have formed a more accurate estimate of their respective merits. This is one of the reasons which gave the Confederates such an immense start in the way of generals; for having formed his opinion with regard to appointing an officer, Mr. Davis is always most determined to carry out his intention in spite of every obstacle. His services in the Mexican war gave him the prestige of a brave man and a good soldier. His services as a statesman pointed him out as the only man who, by his unflinching determination and administrative talent, was able to control the popular will. People speak of any misfortune happening to him as an irreparable evil too dreadful to contemplate....

17th June, Wednesday.--We reached Petersburg at 3 A. M., and had to get out and traverse this town in carts, after which we had to lie down in the road until some other cars were opened. We left Petersburg at 5 A. M. and arrived at Richmond at 7 A. M., having taken forty-one hours coming from Charleston.

The scenery near Richmond is very pretty, and rather English-looking. The view of the James river from the railway bridge is quite beautiful, though the water is rather low at present. The weather was extremely hot and oppressive, and, for the first time since I left Havana, I really suffered from the heat.

Richmond, VA taken in 1862

Richmond, VA taken in 1862I kept my appointment with Mr. Benjamin at 7 o'clock. He is a stout dapper little man, evidently of Hebrew extraction, and of undoubted talent. He is a Louisianian, and was Senator for that State in the old United States Congress, and I believe he is accounted a very clever lawyer and a brilliant orator. He told me that he had filled the onerous post of Secretary of War during the first seven months of the secession, and I can easily believe that he found it no sinecure. We conversed for a long time about the origin of Secession, which he indignantly denied was brought about, as the Yankees assert, by the interested machinations of individuals. He declared that, for the last ten years, the Southern statesmen had openly stated in Congress what would take place; but the Northerners never would believe they were in earnest, and had often replied by the taunt, "The South was so bound to, and dependent on the North, that she couldn't be kicked out of the Union."

Judah P. Benjamin

Judah P. Benjamin He asserted that England had still, and always had had it in her power to terminate the war by recognition, and by making a commercial treaty with the South; and he denied that the Yankees really would dare to go to war with Great Britain for doing so, however much they might swagger about it; he said that recognition would not increase the Yankee hatred of England, for this, whether just or unjust, was already as intense as it could possibly be....

He said the Confederates were more amused than annoyed at the term "rebel," which was so constantly applied to them; but he only wished mildly to remark, that in order to be a "rebel," a person must rebel against some one who has a right to govern him; and he thought it would be very difficult to discover such a right as existing in the Northern over the Southern States.

In order to prepare a treaty of peace, he said, "It would only be necessary to write on a blank sheet of paper the words 'self-government.' Let the Yankees-accord that, and they might fill up the paper in any manner they chose. We don't want any State that doesn't want us; but we only wish that each State should decide fairly upon its own destiny. All we are struggling for is to be let alone."

At 8 P. M. Mr. Benjamin walked with me to the President's dwelling, which is a private house at the other end of the town. I had tea there, and uncommonly good tea, too--the first I had tasted in the Confederacy...

President Jefferson Davis

President Jefferson Davis Mr. Jefferson Davis struck me as looking older than I expected. He is only fifty-six, but his face is emaciated, and much wrinkled. He is nearly six feet high, but is extremely thin, and stoops a little. His features are good, especially his eye, which is very bright, and full of life and humor. I was afterwards told he had lost the sight of his left eye from a recent illness. He wore a linen coat and gray trousers, and he looked what he evidently is, a well-bred gentleman. Nothing can exceed the charm of his manner, which is simple, easy, and most fascinating.

He conversed with me for a long time, and agreed with Benjamin that the Yankees did not really intend to go to war with England if she recognized the South; and he said that, when the inevitable smash came--and that separation was an accomplished fact--the State of Maine would probably try to join Canada, as most of the intelligent people in that State have a horror of being "under the thumb of Massachusetts." He added, that Maine was inhabited by a hardy, thrifty, seafaring population, with different ideas to the people in the other New England States. When I spoke to him of the wretched scenes I had witnessed in his own State (Mississippi), and of the miserable, almost desperate situation in which I had found so many unfortunate women, who had been left behind by their male relations; and when I alluded in admiration to the quiet, calm, uncomplaining manner in which they bore their sufferings and their grief, he said, with much feeling, that he always considered silent despair the most painful description of misery to witness, in the same way that he thought mute insanity was the most awful form of madness.

When I took my leave about 9 o'clock, the President asked me to call upon him again. I don't think it is possible for any one to have an interview with him without going away most favorably impressed by his agreeable, unassuming manners, and by the charm of his conversation. While walking home, Mr. Benjamin told me that Mr. Davis's military instincts still predominate, and that his eager wish was to have joined the army instead of being elected President.

During my travels, many people have remarked to me that Jefferson Davis seems in a peculiar manner adapted for his office. His military education at West Point rendered him intimately acquainted with the higher officers of the army; and his post of Secretary of War under the old government brought officers of all ranks under his immediate personal knowledge and supervision. No man could have formed a more accurate estimate of their respective merits. This is one of the reasons which gave the Confederates such an immense start in the way of generals; for having formed his opinion with regard to appointing an officer, Mr. Davis is always most determined to carry out his intention in spite of every obstacle. His services in the Mexican war gave him the prestige of a brave man and a good soldier. His services as a statesman pointed him out as the only man who, by his unflinching determination and administrative talent, was able to control the popular will. People speak of any misfortune happening to him as an irreparable evil too dreadful to contemplate....

Published on June 17, 2013 14:01

June 12, 2013

Witness to History: Arthur James Lyon Fremantle

AT the outbreak of the American war, in common with many of my countrymen, I felt very indifferent as to which side might win; but if I had any bias, my sympathies were rather in favor of the North, on account of the dislike which an Englishman naturally feels at the idea of slavery. But soon a sentiment of great admiration for the gallantry and determination of the Southerners, together with the unhappy contrast afforded by the foolish bullying conduct of the Northerners, caused a complete revulsion in my feelings, and I was unable to repress a strong wish to go to America and see something of this wonderful struggle.

-- Arthur Fremantle, 1864

Arthur James Lyon Fremantle was a Lieutenant Colonel in the British army who traveled to the Confederacy to observe the Civil War as a neutral. Courted by the Confederate government in hopes he could influence a British intervention Fremantle was given unprecedented access to the highest levels of civilian and military leadership. He kept an amazing diary that was later published in England and both North and South in the divided American states the following year entitled, Three Months in the Southern States: April-June 1863.

Lt. Colonel Arthur James Lyon Fremantle in 1860.

His account is most well known because he was uniquely placed just before and during the battle of Gettysburg to General Lee and his senior officers and gave us one of the finest accounts from the Confederate side. This is why Michael Shaara used Fremantle as one of the key protagonists in his epic novel The Killer Angels in 1974 (superbly portrayed in the film Gettysburg in 1993 based on this book by actor James Lancaster.)

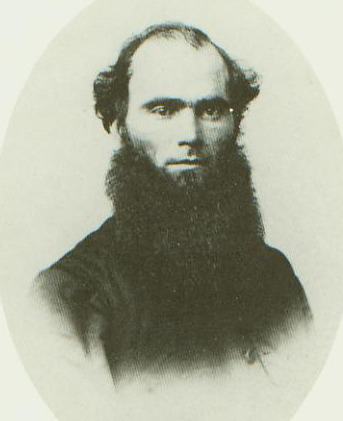

James Lancaster as Colonel Fremantle in the 1993 film Gettysburg.

James Lancaster as Colonel Fremantle in the 1993 film Gettysburg.

What makes the Fremantle diary such an outstanding primary source was his keen eye for detail, and a thoughtful commentary on the people, places and events he was seeing as an outsider. While he was sympathetic to the Confederate cause, he kept his journal impressively objective. It should also be noted it was written without mind for publication. Fremantle published it later in England at the insistence of friends who were curious to know about his American travels.

I think it would be fascinating to use his diary in a series of blog entries as we approach the 150th anniversary of the Gettysburg battle this July.

It is fitting that we begin on an entry regarding slavery. On this day, June 12, 1863, Fremantle had found his way to Charleston, South Carolina where he had arrived on June 8th to meet with General P.G.T. Beauregard. Informed the general was on a trip to Florida but expected to return in a few days Fremantle set about taking in all the sights and meetings he could, inspecting the defensive fortifications and meeting naval officers defending Charleston harbor.

On the 12th he decided to see a slave auction first hand and later was finally able to meet with General Beauregard:

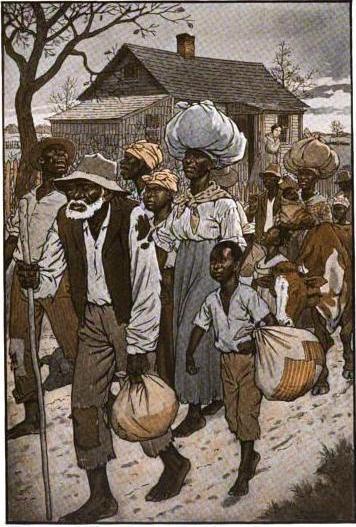

12th June, Friday.--I called at an exchange office this morning, and asked the value of gold; they offered me six to one for it. I went to a slave auction at 11:00... The negroes--about fifteen men, three women, and three children -- were seated on benches, looking perfectly contented and indifferent. I saw the buyers opening the mouths and showing the teeth of their new purchases to their friends in a very business-like manner. This was certainly not a very agreeable spectacle to an Englishman, and I know that many Southerners participate in the same feeling; for I have often been told by people that they had never seen a negro sold by auction, and never wished to do so.

An illustration of a slave auction held in the 1840's.

An illustration of a slave auction held in the 1840's.

It is impossible to mention names in connection with such a subject, but I am perfectly aware that many influential men in the South feel humiliated and annoyed with several of the incidents connected with slavery; and I think that if the Confederate States were left alone, the system would be much modified and amended, although complete emancipation cannot be expected; for the Southerners believe it to be as impracticable to cultivate cotton on a large scale in the South, without forced black labor, as the British have found it to produce sugar in Jamaica; and they declare that the example the English have set them of sudden emancipation in that island is by no means encouraging...

At 1 P. M. I called on General Beauregard, who is a man of middle height, about forty-seven years of age. He would be very youthful in appearance were it not for the color of his hair, which is much grayer than his earlier photographs represent. Some persons account for the sudden manner in which his hair turned grey by allusions to his cares and anxieties during the last two years; but the real and less romantic reason is to be found in the rigidity of the Yankee blockade, which interrupts the arrival of articles of toilet. He has a long straight nose, handsome brown eyes, and a dark mustache without whiskers, and his manners are extremely polite. He is a New Orleans Creole, and French is his native language....

General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard C.S.A.

General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard C.S.A.

He spoke to me of the inevitable necessity, sooner or later, of a war between the Northern States and Great Britain; and he remarked that, if England would join the South at once, the Southern armies relieved of the present blockade and enormous Yankee pressure, would be able to march right into the Northern States, and by occupying their principal cities, would give the Yankees so much employment that they would be unable to spare many men for Canada. He acknowledged that in Mississippi General Grant had displayed uncommon vigor and met with considerable success, considering that he was a man of no great military capacity. He said that Johnston was certainly acting slowly and with much caution; but then he had not the veteran troops of Bragg or Lee.

(to be continued...)

_____________

Read more about the James Fremantle and the Gettysburg campaign my new book for teens just published by Sky Pony Press, Gettysburg: The True Account of Two Young Heroes in the Greatest Battle of the Civil War , available at Amazon and BN.com.

-- Arthur Fremantle, 1864

Arthur James Lyon Fremantle was a Lieutenant Colonel in the British army who traveled to the Confederacy to observe the Civil War as a neutral. Courted by the Confederate government in hopes he could influence a British intervention Fremantle was given unprecedented access to the highest levels of civilian and military leadership. He kept an amazing diary that was later published in England and both North and South in the divided American states the following year entitled, Three Months in the Southern States: April-June 1863.

Lt. Colonel Arthur James Lyon Fremantle in 1860.

His account is most well known because he was uniquely placed just before and during the battle of Gettysburg to General Lee and his senior officers and gave us one of the finest accounts from the Confederate side. This is why Michael Shaara used Fremantle as one of the key protagonists in his epic novel The Killer Angels in 1974 (superbly portrayed in the film Gettysburg in 1993 based on this book by actor James Lancaster.)

James Lancaster as Colonel Fremantle in the 1993 film Gettysburg.

James Lancaster as Colonel Fremantle in the 1993 film Gettysburg. What makes the Fremantle diary such an outstanding primary source was his keen eye for detail, and a thoughtful commentary on the people, places and events he was seeing as an outsider. While he was sympathetic to the Confederate cause, he kept his journal impressively objective. It should also be noted it was written without mind for publication. Fremantle published it later in England at the insistence of friends who were curious to know about his American travels.

I think it would be fascinating to use his diary in a series of blog entries as we approach the 150th anniversary of the Gettysburg battle this July.

It is fitting that we begin on an entry regarding slavery. On this day, June 12, 1863, Fremantle had found his way to Charleston, South Carolina where he had arrived on June 8th to meet with General P.G.T. Beauregard. Informed the general was on a trip to Florida but expected to return in a few days Fremantle set about taking in all the sights and meetings he could, inspecting the defensive fortifications and meeting naval officers defending Charleston harbor.

On the 12th he decided to see a slave auction first hand and later was finally able to meet with General Beauregard:

12th June, Friday.--I called at an exchange office this morning, and asked the value of gold; they offered me six to one for it. I went to a slave auction at 11:00... The negroes--about fifteen men, three women, and three children -- were seated on benches, looking perfectly contented and indifferent. I saw the buyers opening the mouths and showing the teeth of their new purchases to their friends in a very business-like manner. This was certainly not a very agreeable spectacle to an Englishman, and I know that many Southerners participate in the same feeling; for I have often been told by people that they had never seen a negro sold by auction, and never wished to do so.

An illustration of a slave auction held in the 1840's.

An illustration of a slave auction held in the 1840's.

It is impossible to mention names in connection with such a subject, but I am perfectly aware that many influential men in the South feel humiliated and annoyed with several of the incidents connected with slavery; and I think that if the Confederate States were left alone, the system would be much modified and amended, although complete emancipation cannot be expected; for the Southerners believe it to be as impracticable to cultivate cotton on a large scale in the South, without forced black labor, as the British have found it to produce sugar in Jamaica; and they declare that the example the English have set them of sudden emancipation in that island is by no means encouraging...

At 1 P. M. I called on General Beauregard, who is a man of middle height, about forty-seven years of age. He would be very youthful in appearance were it not for the color of his hair, which is much grayer than his earlier photographs represent. Some persons account for the sudden manner in which his hair turned grey by allusions to his cares and anxieties during the last two years; but the real and less romantic reason is to be found in the rigidity of the Yankee blockade, which interrupts the arrival of articles of toilet. He has a long straight nose, handsome brown eyes, and a dark mustache without whiskers, and his manners are extremely polite. He is a New Orleans Creole, and French is his native language....

General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard C.S.A.

General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard C.S.A.He spoke to me of the inevitable necessity, sooner or later, of a war between the Northern States and Great Britain; and he remarked that, if England would join the South at once, the Southern armies relieved of the present blockade and enormous Yankee pressure, would be able to march right into the Northern States, and by occupying their principal cities, would give the Yankees so much employment that they would be unable to spare many men for Canada. He acknowledged that in Mississippi General Grant had displayed uncommon vigor and met with considerable success, considering that he was a man of no great military capacity. He said that Johnston was certainly acting slowly and with much caution; but then he had not the veteran troops of Bragg or Lee.

(to be continued...)

_____________

Read more about the James Fremantle and the Gettysburg campaign my new book for teens just published by Sky Pony Press, Gettysburg: The True Account of Two Young Heroes in the Greatest Battle of the Civil War , available at Amazon and BN.com.

Published on June 12, 2013 14:00

March 28, 2013

Absolution Under Fire: A Moment of Grace at Gettysburg

I'll hang my harp on a willow tree.

I'll off to the wars again:

A peaceful home has no charm for me.

The battlefield no pain

On July 2, 1863, Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia attacked the Union positions along Cemetery Ridge at Gettysburg in a devastating flanking attack striking northeast over the Emmitsburg Road. General Daniel Sickles's Third Corps had advanced without orders along that road forming a salient in front of the main Union defensive line, and were attacked from three sides by Lee's army. Witnessing the devastation in the valley before Cemetery Ridge, Union General Winfield Scott Hancock began organizing reinforcements to advance and rescue the Third Corps from annihilation.

One of those units was the elite Irish Brigade under Colonel Patrick Kelly. The five veteran regiments of this brigade from New York and Massachusetts consisted of almost all Irish immigrants. Among them was Father William Corby, a Catholic priest. As the brigade formed near the wheat field and prepared to advance into the cauldron of battle that lay ahead, Corby recalled, “At this critical moment, I proposed to give a general absolution to our men, as they had absolutely no chance to practice their religious duties during the past two or three weeks, being constantly on the march.”

Father William Corby

Father William Corby

Father Corby stood on a large rock in front of the brigade. Addressing the men, he explained what he was about to do, saying that each one could receive the benefit of the absolution by making a sincere Act of Contrition and firmly resolving to embrace the first opportunity of confessing his sins, urging them to do their duty, and reminding them of the high and sacred nature of their trust as soldiers and the noble object for which they fought. . . . The brigade was standing at “Order arms!” As he closed his address, every man, Catholic and non-Catholic, fell on his knees with his head bowed down. Then, stretching his right hand toward the brigade, Father Corby pronounced the words of the absolution: “Dominus noster Jesus Christus vos absolvat . . .” May our Lord Jesus Christ absolve you; and I by his authority absolve you from every bond of excommunication and interdict, as far as I am able, and you have need. Moreover, I absolve you of your sins, in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.”

Absolution Under Fire by Paul Wood, c. 1891. Print credit: Snite Museum of Art.

Absolution Under Fire by Paul Wood, c. 1891. Print credit: Snite Museum of Art.

In performing this ceremony I faced the army. My eye covered thousands of officers and men. I noticed that all, Catholic and non-Catholic, officers and private soldiers showed a profound respect, wishing at this fatal crisis to receive every benefit of divine grace that could be imparted through the instrumentality of the Church ministry. Even Major General Hancock removed his hat, and, as far as compatible with the situation, bowed in reverential devotion. That general absolution was intended for all—in quantum possum— not only for our brigade, but for all, North or South, who were susceptible of it and who were about to appear before their Judge. -- Father William Corby The Irish Brigade, with the rest of the 1st Division, advanced into the battle moments later and stopped the Confederate attack by nightfall. Of the 530 men of the Irish Brigade, 200 were killed, wounded, or missing by the day’s end. William Corby survived the war and went on to serve two terms as president of the University of Notre Dame. The school’s Corby Hall is named for him. There is a statue dedicated to Corby at Gettysburg memorializing his general absolution to the Irish Brigade on the second day of the battle. He also wrote Memoirs of Chaplain Life: Three Years with the Irish Brigade in the Army of the Potomac. He passed away in 1897.

Memorial to Father William Corby on Cemetery Ridge at Gettysburg. Photo credit: The Gettysburg Daily

Memorial to Father William Corby on Cemetery Ridge at Gettysburg. Photo credit: The Gettysburg Daily

Look for my new book on Gettysburg for teens this June from Sky Pony Press: Gettysburg: The True Account of Two Young Heroes in the Greatest Battle of the Civil War. It can be per-ordered at Amazon, BN.com and Indiebound.

I'll off to the wars again:

A peaceful home has no charm for me.

The battlefield no pain

On July 2, 1863, Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia attacked the Union positions along Cemetery Ridge at Gettysburg in a devastating flanking attack striking northeast over the Emmitsburg Road. General Daniel Sickles's Third Corps had advanced without orders along that road forming a salient in front of the main Union defensive line, and were attacked from three sides by Lee's army. Witnessing the devastation in the valley before Cemetery Ridge, Union General Winfield Scott Hancock began organizing reinforcements to advance and rescue the Third Corps from annihilation.

One of those units was the elite Irish Brigade under Colonel Patrick Kelly. The five veteran regiments of this brigade from New York and Massachusetts consisted of almost all Irish immigrants. Among them was Father William Corby, a Catholic priest. As the brigade formed near the wheat field and prepared to advance into the cauldron of battle that lay ahead, Corby recalled, “At this critical moment, I proposed to give a general absolution to our men, as they had absolutely no chance to practice their religious duties during the past two or three weeks, being constantly on the march.”

Father William Corby

Father William CorbyFather Corby stood on a large rock in front of the brigade. Addressing the men, he explained what he was about to do, saying that each one could receive the benefit of the absolution by making a sincere Act of Contrition and firmly resolving to embrace the first opportunity of confessing his sins, urging them to do their duty, and reminding them of the high and sacred nature of their trust as soldiers and the noble object for which they fought. . . . The brigade was standing at “Order arms!” As he closed his address, every man, Catholic and non-Catholic, fell on his knees with his head bowed down. Then, stretching his right hand toward the brigade, Father Corby pronounced the words of the absolution: “Dominus noster Jesus Christus vos absolvat . . .” May our Lord Jesus Christ absolve you; and I by his authority absolve you from every bond of excommunication and interdict, as far as I am able, and you have need. Moreover, I absolve you of your sins, in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.”

Absolution Under Fire by Paul Wood, c. 1891. Print credit: Snite Museum of Art.

Absolution Under Fire by Paul Wood, c. 1891. Print credit: Snite Museum of Art. In performing this ceremony I faced the army. My eye covered thousands of officers and men. I noticed that all, Catholic and non-Catholic, officers and private soldiers showed a profound respect, wishing at this fatal crisis to receive every benefit of divine grace that could be imparted through the instrumentality of the Church ministry. Even Major General Hancock removed his hat, and, as far as compatible with the situation, bowed in reverential devotion. That general absolution was intended for all—in quantum possum— not only for our brigade, but for all, North or South, who were susceptible of it and who were about to appear before their Judge. -- Father William Corby The Irish Brigade, with the rest of the 1st Division, advanced into the battle moments later and stopped the Confederate attack by nightfall. Of the 530 men of the Irish Brigade, 200 were killed, wounded, or missing by the day’s end. William Corby survived the war and went on to serve two terms as president of the University of Notre Dame. The school’s Corby Hall is named for him. There is a statue dedicated to Corby at Gettysburg memorializing his general absolution to the Irish Brigade on the second day of the battle. He also wrote Memoirs of Chaplain Life: Three Years with the Irish Brigade in the Army of the Potomac. He passed away in 1897.

Memorial to Father William Corby on Cemetery Ridge at Gettysburg. Photo credit: The Gettysburg Daily

Memorial to Father William Corby on Cemetery Ridge at Gettysburg. Photo credit: The Gettysburg DailyLook for my new book on Gettysburg for teens this June from Sky Pony Press: Gettysburg: The True Account of Two Young Heroes in the Greatest Battle of the Civil War. It can be per-ordered at Amazon, BN.com and Indiebound.

Published on March 28, 2013 12:43

March 8, 2013

George Gordon Meade: The Unsung Hero of Gettysburg

Batteries are all about us; troops are moving into position;

new lines seem to be forming, or old ones extending. Two or three

general officers, with a retinue of staff and orderlies, come galloping

by. Foremost is the spare and somewhat stooped form of the

Commanding General. He is not cheered, indeed he is scarcely

recognized. He is an approved corps General, but he has not yet

vindicated his right to command the Army of the Potomac.

—Whitelaw Reid, Cincinnati Gazette

Major General George Gordon Meade, illustrated by Ron Cole.

Major General George Gordon Meade, illustrated by Ron Cole.

One of the great unsung heroes of Gettysburg is Major General George Gordon Meade. In the pre-dawn hours of June 28, 1863, a special messenger reached Meade, who was encamped with the army near Frederick, Maryland. So stunned was Meade, in his sleepy mind, that he thought the officer had come to place him under arrest. Instead he was delivered a letter from General Halleck in which Meade was promoted to command the Army of the Potomac with orders to confront Lee as he invaded Pennsylvania. Unknown to anyone, that confrontation was only three days away.

Although Meade was known for his temper, nicknamed a damned "goggle-eyed snapping turtle" by some on his staff, he was an inspired choice by Lincoln. Meade was a proven combat leader, one without political ambitions, and Lincoln knew he could count on Meade to defend his home state of Pennsylvania from Lee’s invasion. Where other generals had shown timidity in opposing Lee aggressively, Meade knew his duty was to seek battle. This was well understood by General Lee, a fellow West Pointer and engineer, who found out Meade had taken command about twenty-four hours later. Lee said to his corps commanders, “General Meade will commit no blunder in my front, and if I make one he will make haste to take advantage of it.”

Meade also had the confidence of his fellow officers, especially Major Generals John Reynolds and Winfield Scott Hancock. That same trust was returned by Meade giving Reynolds command of the left wing as they advanced towards Gettysburg with authority to act in Meade's stead on the battlefield. When word of Reynold's death reached Meade, he turned to Hancock to take command of the field and confront Lee until the situation developed. By the time Meade arrived on the battlefield before dawn on July 2, his army was in possession of the high ground from Culp's Hill, along Cemetery Ridge to the Round Tops. Hancock's presence had been a major factor in rallying the survivors of the First Corps and placing reinforcements into line along Cemetery Ridge.

On the night of June 30, just before the battle, he wrote his wife: “All is going on well. I think I have relieved Harrisburg and Philadelphia, and that Lee has now come to the conclusion that he must attend to other matters. I continue well, but much oppressed with a sense of responsibility and the magnitude of the great interests entrusted to me . . . Pray for me and beseech our heavenly Father to permit me to be an instrument to save my country and advance a just cause.”

Commanders of the Army of the Potomac, Gouverneur K. Warren, William H. French, George G. Meade, Henry J. Hunt, Andrew A. Humphreys, and George Sykes in September 1863.

Commanders of the Army of the Potomac, Gouverneur K. Warren, William H. French, George G. Meade, Henry J. Hunt, Andrew A. Humphreys, and George Sykes in September 1863.

Meade should be remembered as one of the great Civil War generals. He was one of the few combat leaders who appreciated changes in technology and tactics that made frontal assaults a tragic waste of human lives. At Gettysburg, when the country needed fighting leader, Meade was there. His trust in his subordinates, his careful movement and deployment of vast numbers of men, guns, and supplies to Gettysburg, and his foresight in sensing Lee would attack his center line on July 3, were all marks of a great general. He was one of the few Union generals to face Robert E. Lee in open battle and to defeat him.

new lines seem to be forming, or old ones extending. Two or three

general officers, with a retinue of staff and orderlies, come galloping

by. Foremost is the spare and somewhat stooped form of the

Commanding General. He is not cheered, indeed he is scarcely

recognized. He is an approved corps General, but he has not yet

vindicated his right to command the Army of the Potomac.

—Whitelaw Reid, Cincinnati Gazette

Major General George Gordon Meade, illustrated by Ron Cole.

Major General George Gordon Meade, illustrated by Ron Cole. One of the great unsung heroes of Gettysburg is Major General George Gordon Meade. In the pre-dawn hours of June 28, 1863, a special messenger reached Meade, who was encamped with the army near Frederick, Maryland. So stunned was Meade, in his sleepy mind, that he thought the officer had come to place him under arrest. Instead he was delivered a letter from General Halleck in which Meade was promoted to command the Army of the Potomac with orders to confront Lee as he invaded Pennsylvania. Unknown to anyone, that confrontation was only three days away.

Although Meade was known for his temper, nicknamed a damned "goggle-eyed snapping turtle" by some on his staff, he was an inspired choice by Lincoln. Meade was a proven combat leader, one without political ambitions, and Lincoln knew he could count on Meade to defend his home state of Pennsylvania from Lee’s invasion. Where other generals had shown timidity in opposing Lee aggressively, Meade knew his duty was to seek battle. This was well understood by General Lee, a fellow West Pointer and engineer, who found out Meade had taken command about twenty-four hours later. Lee said to his corps commanders, “General Meade will commit no blunder in my front, and if I make one he will make haste to take advantage of it.”

Meade also had the confidence of his fellow officers, especially Major Generals John Reynolds and Winfield Scott Hancock. That same trust was returned by Meade giving Reynolds command of the left wing as they advanced towards Gettysburg with authority to act in Meade's stead on the battlefield. When word of Reynold's death reached Meade, he turned to Hancock to take command of the field and confront Lee until the situation developed. By the time Meade arrived on the battlefield before dawn on July 2, his army was in possession of the high ground from Culp's Hill, along Cemetery Ridge to the Round Tops. Hancock's presence had been a major factor in rallying the survivors of the First Corps and placing reinforcements into line along Cemetery Ridge.

On the night of June 30, just before the battle, he wrote his wife: “All is going on well. I think I have relieved Harrisburg and Philadelphia, and that Lee has now come to the conclusion that he must attend to other matters. I continue well, but much oppressed with a sense of responsibility and the magnitude of the great interests entrusted to me . . . Pray for me and beseech our heavenly Father to permit me to be an instrument to save my country and advance a just cause.”

Commanders of the Army of the Potomac, Gouverneur K. Warren, William H. French, George G. Meade, Henry J. Hunt, Andrew A. Humphreys, and George Sykes in September 1863.

Commanders of the Army of the Potomac, Gouverneur K. Warren, William H. French, George G. Meade, Henry J. Hunt, Andrew A. Humphreys, and George Sykes in September 1863.Meade should be remembered as one of the great Civil War generals. He was one of the few combat leaders who appreciated changes in technology and tactics that made frontal assaults a tragic waste of human lives. At Gettysburg, when the country needed fighting leader, Meade was there. His trust in his subordinates, his careful movement and deployment of vast numbers of men, guns, and supplies to Gettysburg, and his foresight in sensing Lee would attack his center line on July 3, were all marks of a great general. He was one of the few Union generals to face Robert E. Lee in open battle and to defeat him.

Published on March 08, 2013 13:57

March 1, 2013

Great Authors: Erich Maria Remarque Part One

Do they matter?—those dreams from the pit?...

You can drink and forget and be glad,

And people won’t say that you’re mad;

For they’ll know you’ve fought for your country

And no one will worry a bit.

--Siegfried Sassoon

Every writer has somewhere a small collection of cherished books--authors whose influence runs deep. I firmly believe that books find their way into our lives at certain times to inspire us. One of the life changing times that put me on the path to studying history can in the 8th grade. I was living in Stockholm at the time, attending The International School learning history from Mrs Anderson. She was a kindly and learned woman who cared deeply about her convictions against war. I'll never forget her.

She read us a passage from Erich Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front. I still remember the passage (see below). Decades later I still regard that novel as one of the greatest books ever written. Remarque served on the western front with the German army and later became a teacher. He wrote his epic novel in 1927. The Nazis banned his book and would have arrested Remarque but he was living in Switzerland. His sister Elfriede was arrested and tried by the Nazis in 1943 for opposing the war. Found guilty by one of Hitler's "People's Courts" she was executed. Remarque and his wife emigrated to the United States in 1947 and became citizens although he returned to Switzerland in 1949 where he spent the rest of his life.

Remarque in Davos, Switzerland, 1929.

Remarque in Davos, Switzerland, 1929.

"Erich Maria Remarque is in many ways the quintessential twentieth-century man. Caught between the intense nineteenth-century nationalism of his youth and the dissolution and despair brought on by World War I, Remarque embodies the psychological and existential dilemmas of his generation."

--Marvin J.Taylor, New York University.

In this passage, the story's central character, Paul Baumer is recovering from wounds received on the battlefield and is assigned to a hospital behind the lines. I wonder how many young men (and women) who have suffered in our recent wars feel exactly the same way?

On the next floor below are the abdominal and spine cases, head wounds and double amputations. On the right side of the wing are the jaw wounds, gas cases, nose, ear, and neck wounds. On the left the blind and the lung wounds, pelvis wounds, wounds in the joints, wounds in the kidneys, wounds in the testicles, wounds in the intestines. Here a man realizes for the first time in how many places a man can get hit...

And this is only one hospital, one single station; there are hundreds of thousands in Germany, hundreds of thousands in France, hundreds of thousands in Russia. How senseless is everything that can ever be written, done, or thought, when such things are possible. It must be all lies and of no account when the culture of a thousand years could not prevent this stream of blood being poured out, these torture-chambers in their hundreds of thousands. A hospital alone shows what war is.

I am young, I am twenty years old; yet I know nothing of life but despair, death, fear, and fatuous superficiality cast over an abyss of sorrow. I see how peoples are set against one another, and in silence, unknowingly, foolishly, obediently, innocently slay one another. I see that the keenest brains of the world invent weapons and words to make it yet more refined and enduring. And all men of my age, here and over there, throughout the whole world see these things; all my generation is experiencing these things with me. What would our fathers do if we suddenly stood up and came before them and proffered our account? What do they expect of us if a time ever comes when the war is over? Through the years our business has been killing;--it was our first calling in life. Our knowledge of life is limited to death. What will happen afterwards? And what shall come out of us?

...To be Continued...

You can drink and forget and be glad,

And people won’t say that you’re mad;

For they’ll know you’ve fought for your country

And no one will worry a bit.

--Siegfried Sassoon

Every writer has somewhere a small collection of cherished books--authors whose influence runs deep. I firmly believe that books find their way into our lives at certain times to inspire us. One of the life changing times that put me on the path to studying history can in the 8th grade. I was living in Stockholm at the time, attending The International School learning history from Mrs Anderson. She was a kindly and learned woman who cared deeply about her convictions against war. I'll never forget her.

She read us a passage from Erich Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front. I still remember the passage (see below). Decades later I still regard that novel as one of the greatest books ever written. Remarque served on the western front with the German army and later became a teacher. He wrote his epic novel in 1927. The Nazis banned his book and would have arrested Remarque but he was living in Switzerland. His sister Elfriede was arrested and tried by the Nazis in 1943 for opposing the war. Found guilty by one of Hitler's "People's Courts" she was executed. Remarque and his wife emigrated to the United States in 1947 and became citizens although he returned to Switzerland in 1949 where he spent the rest of his life.

Remarque in Davos, Switzerland, 1929.

Remarque in Davos, Switzerland, 1929."Erich Maria Remarque is in many ways the quintessential twentieth-century man. Caught between the intense nineteenth-century nationalism of his youth and the dissolution and despair brought on by World War I, Remarque embodies the psychological and existential dilemmas of his generation."

--Marvin J.Taylor, New York University.

In this passage, the story's central character, Paul Baumer is recovering from wounds received on the battlefield and is assigned to a hospital behind the lines. I wonder how many young men (and women) who have suffered in our recent wars feel exactly the same way?

On the next floor below are the abdominal and spine cases, head wounds and double amputations. On the right side of the wing are the jaw wounds, gas cases, nose, ear, and neck wounds. On the left the blind and the lung wounds, pelvis wounds, wounds in the joints, wounds in the kidneys, wounds in the testicles, wounds in the intestines. Here a man realizes for the first time in how many places a man can get hit...

And this is only one hospital, one single station; there are hundreds of thousands in Germany, hundreds of thousands in France, hundreds of thousands in Russia. How senseless is everything that can ever be written, done, or thought, when such things are possible. It must be all lies and of no account when the culture of a thousand years could not prevent this stream of blood being poured out, these torture-chambers in their hundreds of thousands. A hospital alone shows what war is.

I am young, I am twenty years old; yet I know nothing of life but despair, death, fear, and fatuous superficiality cast over an abyss of sorrow. I see how peoples are set against one another, and in silence, unknowingly, foolishly, obediently, innocently slay one another. I see that the keenest brains of the world invent weapons and words to make it yet more refined and enduring. And all men of my age, here and over there, throughout the whole world see these things; all my generation is experiencing these things with me. What would our fathers do if we suddenly stood up and came before them and proffered our account? What do they expect of us if a time ever comes when the war is over? Through the years our business has been killing;--it was our first calling in life. Our knowledge of life is limited to death. What will happen afterwards? And what shall come out of us?

...To be Continued...

Published on March 01, 2013 13:12

February 26, 2013

Lee Advanced to Gettysburg on the Word of a Spy

Great events sometimes turn on comparatively small affairs.

--Colonel William Calvin Oates, 15th Alabama Infantry

One of the great rewards of writing non-fiction is that the process forces a much deeper understanding of the subject at hand than one might otherwise achieve. The absence of JEB Stuart's cavalry as Lee marched into Pennsylvania has always been one of the most debated and contentious subjects of Civil War history. Lee in fact, in a rare post war commentary, stated that Stuart's refusal to obey instructions was the number one reason the Confederacy lost the Gettysburg campaign. Anyone who has studied Robert E. Lee and the facts will know this was not a whitewashing of Lee's own failures. Paramount here is that if Stuart had stayed close to Lee's forces he would have been better informed as to his enemy's movements, but also the nature of the terrain before his own army possibly allowing him to choose the location of the engagement.

Robert E. Lee 1862 photo, illustrated by Ron Cole.

Robert E. Lee 1862 photo, illustrated by Ron Cole.What came to light while researching for my new book was how deeply this failure of Stuart was ingrained on the high command of the Confederate army even before the battle and in the contentious decades that followed. Two interesting quotes found their way into the new book:

The failure to crush the Federal army in Pennsylvania in 1863, in the opinion of almost all of the officers of the Army of Northern Virginia, can be expressed in five words—the absence of the cavalry.

—Major General Henry Heth

Stuart was on a useless, showy parade almost under the guns of the Washington

forts . . .

When he rejoined Lee it was with exhausted horses and half worn-out men in the closing hours of Gettysburg.

Had he been with Lee where would our commander have made his battle? Possibly, not on that unfavorable ground of Gettysburg. Lee with his personally weak opponent, and Stuart by him, could almost have chosen the spot where he would be sure to defeat the Union Army.

—Lieutenant Colonel Moxley Sorrel

General Heth had his own good reasons to assign blame on another officer since it was on his orders on July 1 that recklessly sent two brigades of his division into battle at Gettysburg in spite of Lee's wishes to avoid a fight. Yet it is interesting because it shows that this opinion was widely held among the other officers.

Sorrel's comment is truly inspired. In a few words he captures the strategic situation Lee faced as he entered Pennsylvania. The location of the battlefield was as crucial as knowing the enemy's whereabouts as events surely proved. Sorrel's account is also interesting because he showed what a momentous decision was forced upon Lee a few nights before the battle when word of the Army of the Potomac's movements reached him by word of a spy, a man he had never met, vouched for only by General Longstreet.

Lieutenant Colonel Moxley Sorrel

Lieutenant Colonel Moxley SorrelFrom Gettysburg: The True Account of Two Young Heroes in the Greatest Battle of the Civil War:

On Sunday, June 28th Robert E. Lee arrived at Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where the corps of Longstreet and A.P. Hill were encamped. He established headquarters in a quite grove called Messersmith’s Woods. Lieutenant William Owen, an artillery officer in Longstreet’s command, described the scene:

The general has little of the pomp and circumstance of war about his person. A Confederate flag marks the whereabouts of his headquarters, which are here in a little enclosure of some couple of acres of timber. There are about half a dozen tents and as many baggage wagons and ambulances. . . Lee was evidently annoyed at the absence of Stuart and the cavalry, and asked several officers, myself among the number, if we knew anything of the whereabouts of Stuart. The eyes and ears of the army are evidently missing and are greatly needed by the commander.

That night a mysterious stranger was brought to Longstreet’s chief of staff, Lieutenant Colonel Moxley Sorrel:

At night I was roused by a detail of the provost guard bringing up a suspicious prisoner. I knew him instantly; it was Harrison, the scout, filthy and ragged . . . He had come to ‘Report to the General, who was sure to be with the army,’ and truly his report was long and valuable.

The Federal army had crossed the Potomac three days ago and was far into Maryland. Harrison knew the locations of five of the enemy’s seven army corps. Three were already at Frederick with two more marching north from Frederick toward South Mountain. He also brought news that General Meade had taken command of the army. This information was already twenty-four hours old.

Lee had not heard from Stuart for three days now. Stuart had never before failed him. But even now Lee was unaware of Stuart’s location, and he had only the word of a paid spy on which to plan his next move. The time for action had come, though, and Lee did not hesitate. Sorrel noted:

It was on this, the report of a single scout, in the absence of cavalry, that the army moved . . . [Lee] sent orders to bring Ewell immediately back from the North about Harrisburg, and join his left. Then he started A. P. Hill off at sunrise for Gettysburg, followed by Longstreet. The enemy was there, and there our General would strike him.

[ Gettysburg: The True Account of Two Young Heroes in the Greatest Battle of the Civil War is being published by Sky Pony Press, June 1, 2013--a Young Adult title for ages 12-16.]

Henry T. Harrison in uniform, 1863.

Henry T. Harrison in uniform, 1863.The image of Harrison is sources from the website of his great grandson Bernie Becker:

http://home.comcast.net/~site002/Harr...

Published on February 26, 2013 12:34

February 20, 2013

Daniel Skelly: A Young Gettysburg Hero Part Two

So wise so young, they say, do never live long.

― William Shakespeare, Richard III

Daniel Skelly was an 18 year old clerk working at the Fahnestock Brothers dry goods store in Gettysburg in July, 1863. In our first post, Daniel explained that rumors of the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania were rife in the weeks before the battle. On June 30th, he witnessed the arrival of General John Buford's two brigades of Union cavalry and thought the town and its people would surely be safe from Lee's army. Little did he know that two entire Confederate corps were converging on Gettysburg the following day. Units of the Union's First Corps were encamped just eight miles east of Gettysburg with orders to advance to the town by morning. The world was about to explode on July 1st.

Daniel Skelly

Daniel Skelly

What did this all mean to an excitable eighteen year-old boy? The chance to see a real battle! And where better than to see a battle than where the battle was happening? The morning of July 1st Daniel and a friend ran toward the Union lines to see what they could see... From Daniel's memoir:

I went directly across the fields to Seminary Ridge . . . just where the old railroad cut through it. The ridge was full of men and boys from town, all eager to witness a brush with the Confederates and not dreaming of the terrible conflict that was to occur on that day and not having the slightest conception

of the proximity of the two armies.

I climbed up a good-sized oak tree so as to have a good view of the ridge west and northwest of us, where the two brigades of cavalry were then being placed. We could then hear distinctly the skirmish fire in the vicinity of Marsh Creek, about three miles from our position and could tell that it was approaching nearer and nearer as our skirmishers fell back slowly toward the town contesting every inch of ground. We could see clearly on the ridge . . . the formation of the line of battle of Buford’s Cavalry, which had dismounted, some of the men taking charge of the horses and the others forming a line of battle, acting as infantry.

Nearer and nearer came the skirmish line as it fell back before the advancing Confederates, until at last the line on the ridge beyond became engaged. Soon the artillery opened fire and shot and shell began to fly over our heads, one of them passing dangerously near the top of the tree I was on. There was a general stampede toward town and I quickly slipped down from my perch and joined the retreat to the rear of our gallant men and boys . . . a cannon ball struck the earth about fifteen or twenty feet from me, scattering the ground somewhat about me and quickening my pace considerably.

.... to be continued.

― William Shakespeare, Richard III

Daniel Skelly was an 18 year old clerk working at the Fahnestock Brothers dry goods store in Gettysburg in July, 1863. In our first post, Daniel explained that rumors of the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania were rife in the weeks before the battle. On June 30th, he witnessed the arrival of General John Buford's two brigades of Union cavalry and thought the town and its people would surely be safe from Lee's army. Little did he know that two entire Confederate corps were converging on Gettysburg the following day. Units of the Union's First Corps were encamped just eight miles east of Gettysburg with orders to advance to the town by morning. The world was about to explode on July 1st.

Daniel Skelly

Daniel SkellyWhat did this all mean to an excitable eighteen year-old boy? The chance to see a real battle! And where better than to see a battle than where the battle was happening? The morning of July 1st Daniel and a friend ran toward the Union lines to see what they could see... From Daniel's memoir:

I went directly across the fields to Seminary Ridge . . . just where the old railroad cut through it. The ridge was full of men and boys from town, all eager to witness a brush with the Confederates and not dreaming of the terrible conflict that was to occur on that day and not having the slightest conception

of the proximity of the two armies.

I climbed up a good-sized oak tree so as to have a good view of the ridge west and northwest of us, where the two brigades of cavalry were then being placed. We could then hear distinctly the skirmish fire in the vicinity of Marsh Creek, about three miles from our position and could tell that it was approaching nearer and nearer as our skirmishers fell back slowly toward the town contesting every inch of ground. We could see clearly on the ridge . . . the formation of the line of battle of Buford’s Cavalry, which had dismounted, some of the men taking charge of the horses and the others forming a line of battle, acting as infantry.

Nearer and nearer came the skirmish line as it fell back before the advancing Confederates, until at last the line on the ridge beyond became engaged. Soon the artillery opened fire and shot and shell began to fly over our heads, one of them passing dangerously near the top of the tree I was on. There was a general stampede toward town and I quickly slipped down from my perch and joined the retreat to the rear of our gallant men and boys . . . a cannon ball struck the earth about fifteen or twenty feet from me, scattering the ground somewhat about me and quickening my pace considerably.

.... to be continued.

Published on February 20, 2013 08:11

January 25, 2013

Elizabeth Salome Myers: A Gettysburg Hero Part Two

Do not be afraid; our fate

Cannot be taken from us; it is a gift.

― Dante Alighieri, Inferno

Elizabeth "Sallie" Myers

Elizabeth "Sallie" Myers

...Continuing the true story of Sallie Myers, the fighting in and around Gettysburg had subsided by late afternoon. Wounded from both sides were being brought into any structure that would shelter them in town--thousands of casualties.

Sallie Myers was called along with other women to assist the wounded. The Catholic church was just down the street from her father’s home and she went to volunteer however she could. She had always feared the sight of blood and was terrified what might be asked of her. From her diary:

On pews and floors men lay, the groans of the suffering and dying were heartrending. I knelt beside the first man near the door and asked what I could do. “Nothing,” he replied, “I am going to die.” I went outside the church and cried. I returned and spoke to the man—he was wounded in the lungs and spine, and there was not the slightest hope for him. The man was Sergeant Alexander Stewart of the 149th Pennsylvania Volunteers. I read a chapter of the Bible to him, it was the last chapter his father had read before he left home. The wounded man died on Monday, July 6th.

Sergeant Stewart was the first wounded man brought in, but others followed. The sight of blood never again affected me and I was among wounded and dying men day and night. While the battle lasted and the town was in possession of the rebels, I went back and forth between my home and the hospitals without fear. The soldiers called me brave, but I am afraid the truth was that I did not know enough to be afraid and if I had known enough, I had no time to think of the risk I ran, for my heart and hands were full.

I went daily through the hospitals with my writing materials, reading and answering letters. This work enlisted all my sympathies, and I received many kind and appreciative letters from those who could not come. Besides caring for the wounded, we did all we could for the comfort of friends who came to look after their loved ones.

I would not care to live that summer again, yet I would not willingly erase that chapter from my life's experience; and I shall always be thankful that I was permitted to minister to the wants and soothe the last hours of some of the brave men who lay suffering and dying for the dear old flag.

Elizabeth received a letter from Alexander's younger brother after the battle, Henry Stewart who was a preacher. He arrived in Gettysburg the following summer with his mother to see to Alexander's grave. Elizabeth had become close to Henry through their letters and a romance began after they met. They were married in 1867, and although Henry was not to live for more than a year, she had a son in 1869 named Henry Alexander Stewart.

Nationally recognized for her efforts to help the wounded at Gettysburg she eventually returned to teaching and worked with the National Association of Army Nurses. She passed away in 1922 and is buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Gettysburg. She never remarried. Her son Henry became a doctor. Her account of Gettysburg was published in 1903: How A Gettysburg Schoolteacher Spent Her Vacation in 1863.

Cannot be taken from us; it is a gift.

― Dante Alighieri, Inferno

Elizabeth "Sallie" Myers

Elizabeth "Sallie" Myers...Continuing the true story of Sallie Myers, the fighting in and around Gettysburg had subsided by late afternoon. Wounded from both sides were being brought into any structure that would shelter them in town--thousands of casualties.

Sallie Myers was called along with other women to assist the wounded. The Catholic church was just down the street from her father’s home and she went to volunteer however she could. She had always feared the sight of blood and was terrified what might be asked of her. From her diary:

On pews and floors men lay, the groans of the suffering and dying were heartrending. I knelt beside the first man near the door and asked what I could do. “Nothing,” he replied, “I am going to die.” I went outside the church and cried. I returned and spoke to the man—he was wounded in the lungs and spine, and there was not the slightest hope for him. The man was Sergeant Alexander Stewart of the 149th Pennsylvania Volunteers. I read a chapter of the Bible to him, it was the last chapter his father had read before he left home. The wounded man died on Monday, July 6th.

Sergeant Stewart was the first wounded man brought in, but others followed. The sight of blood never again affected me and I was among wounded and dying men day and night. While the battle lasted and the town was in possession of the rebels, I went back and forth between my home and the hospitals without fear. The soldiers called me brave, but I am afraid the truth was that I did not know enough to be afraid and if I had known enough, I had no time to think of the risk I ran, for my heart and hands were full.

I went daily through the hospitals with my writing materials, reading and answering letters. This work enlisted all my sympathies, and I received many kind and appreciative letters from those who could not come. Besides caring for the wounded, we did all we could for the comfort of friends who came to look after their loved ones.

I would not care to live that summer again, yet I would not willingly erase that chapter from my life's experience; and I shall always be thankful that I was permitted to minister to the wants and soothe the last hours of some of the brave men who lay suffering and dying for the dear old flag.

Elizabeth received a letter from Alexander's younger brother after the battle, Henry Stewart who was a preacher. He arrived in Gettysburg the following summer with his mother to see to Alexander's grave. Elizabeth had become close to Henry through their letters and a romance began after they met. They were married in 1867, and although Henry was not to live for more than a year, she had a son in 1869 named Henry Alexander Stewart.

Nationally recognized for her efforts to help the wounded at Gettysburg she eventually returned to teaching and worked with the National Association of Army Nurses. She passed away in 1922 and is buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Gettysburg. She never remarried. Her son Henry became a doctor. Her account of Gettysburg was published in 1903: How A Gettysburg Schoolteacher Spent Her Vacation in 1863.

Published on January 25, 2013 13:14

January 17, 2013

Elizabeth Salome Myers: A Gettysburg Hero Part One

Courage is grace under pressure.

― Ernest Hemingway

People are always moved by the courage of everyday people doing a heroic act to help someone. A few years ago, a 50-year-old construction worker named Wesley Autrey became a New York hero when he rescued a man who had fallen onto the subway tracks. With total disregard for his own safety he leaped into the path of an onrushing train to save a complete stranger.

That is raw courage, to put oneself in harm's way to save the life of another person.

But there is another kind of courage--the courage to face down one's own fears. Some of us fear the dark, or fire, while others cringe at the even the suggestion of a spider. If we had to face one of our own greatest fears in order to help someone, would we all have the same courage to do what is right in the event of a emergency?

Elizabeth Salome Meyers was just like most of us. She was from a well-to-do family that lived in Gettysburg in 1863. Just 21 years old, she was a devoted school teacher. "Sallie" had never been witness to much suffering in life. She was terrified by the sight of blood. Yet she would take part in the battle of Gettysburg and overcome her fears to do whatever was required to assist the wounded. Gettysburg would become the defining moment of her entire life, and she would devote all her remaining years to the study and practice of nursing.

When the Confederates moved to occupy Gettysburg on the morning of July 1, they were opposed by two brigades of Union cavalry. The Federals were soon reinforced by an entire corps of 20,000 men. By mid afternoon both armies were locked in a savage fight for control of the lands just outside town. When the Union army began to fall back through Gettysburg, the people realized their streets would soon become the next battlefield. Trapped between two massive armies, the townspeople took shelter in their cellars and prayed.

From her diary of July 1, 1863:

While our elders prepared food, we girls stood on the corner near our house and gave refreshments of all kinds to ‘our boys’ of the First Corps, who were double-quicking down Washington Street to join the troops already engaged in battle west of the town. After the men had all passed, we sat on our doorsteps or stood around in groups, frightened nearly out of our wits but never dreaming of defeat.

"Water for the Marching Troops", from Clifton Johnson's Battlefield Adventures, 1915.

"Water for the Marching Troops", from Clifton Johnson's Battlefield Adventures, 1915.

At 10 o'clock that morning I saw the first blood. A horse was led past our house covered with blood. The sight sickened me. Then three men came up the street. The middle one could barely walk. His head had been hastily bandaged and blood was visible. I grew faint with horror. I had never been able to stand the sight of blood, but I was destined to become used to it.

Then came the order: ‘Women and children to the cellars; the rebels will shell the town.’ We lost little time in obeying the order. My home was on West High Street, near Washington (Street) and in the direct path of the retreat (of the Union Army).

We knelt, shivering, and prayed. The noise above our heads and from the distance, the rattle of musketry, the screeching of shells, and the unearthly cries, mingled with the sobbing of the children shook our hearts. Three soldiers crept down into the cellar, and we concealed and fed them.

After the Rebels had gained full possession of the town, some of our men who had been captured were standing near the cellar window. One of them asked if some of us would take their addresses and the addresses of friends and write to them of their capture. I took thirteen and wrote as they requested. I received answers from all but one, and several of the soldiers revisited the place of their capture and recognized the house and cellar window. While the battle lasted we concealed and fed three men in our cellar.

... to be continued.

― Ernest Hemingway

People are always moved by the courage of everyday people doing a heroic act to help someone. A few years ago, a 50-year-old construction worker named Wesley Autrey became a New York hero when he rescued a man who had fallen onto the subway tracks. With total disregard for his own safety he leaped into the path of an onrushing train to save a complete stranger.

That is raw courage, to put oneself in harm's way to save the life of another person.

But there is another kind of courage--the courage to face down one's own fears. Some of us fear the dark, or fire, while others cringe at the even the suggestion of a spider. If we had to face one of our own greatest fears in order to help someone, would we all have the same courage to do what is right in the event of a emergency?

Elizabeth Salome Meyers was just like most of us. She was from a well-to-do family that lived in Gettysburg in 1863. Just 21 years old, she was a devoted school teacher. "Sallie" had never been witness to much suffering in life. She was terrified by the sight of blood. Yet she would take part in the battle of Gettysburg and overcome her fears to do whatever was required to assist the wounded. Gettysburg would become the defining moment of her entire life, and she would devote all her remaining years to the study and practice of nursing.

When the Confederates moved to occupy Gettysburg on the morning of July 1, they were opposed by two brigades of Union cavalry. The Federals were soon reinforced by an entire corps of 20,000 men. By mid afternoon both armies were locked in a savage fight for control of the lands just outside town. When the Union army began to fall back through Gettysburg, the people realized their streets would soon become the next battlefield. Trapped between two massive armies, the townspeople took shelter in their cellars and prayed.

From her diary of July 1, 1863:

While our elders prepared food, we girls stood on the corner near our house and gave refreshments of all kinds to ‘our boys’ of the First Corps, who were double-quicking down Washington Street to join the troops already engaged in battle west of the town. After the men had all passed, we sat on our doorsteps or stood around in groups, frightened nearly out of our wits but never dreaming of defeat.

"Water for the Marching Troops", from Clifton Johnson's Battlefield Adventures, 1915.

"Water for the Marching Troops", from Clifton Johnson's Battlefield Adventures, 1915.At 10 o'clock that morning I saw the first blood. A horse was led past our house covered with blood. The sight sickened me. Then three men came up the street. The middle one could barely walk. His head had been hastily bandaged and blood was visible. I grew faint with horror. I had never been able to stand the sight of blood, but I was destined to become used to it.

Then came the order: ‘Women and children to the cellars; the rebels will shell the town.’ We lost little time in obeying the order. My home was on West High Street, near Washington (Street) and in the direct path of the retreat (of the Union Army).

We knelt, shivering, and prayed. The noise above our heads and from the distance, the rattle of musketry, the screeching of shells, and the unearthly cries, mingled with the sobbing of the children shook our hearts. Three soldiers crept down into the cellar, and we concealed and fed them.

After the Rebels had gained full possession of the town, some of our men who had been captured were standing near the cellar window. One of them asked if some of us would take their addresses and the addresses of friends and write to them of their capture. I took thirteen and wrote as they requested. I received answers from all but one, and several of the soldiers revisited the place of their capture and recognized the house and cellar window. While the battle lasted we concealed and fed three men in our cellar.

... to be continued.

Published on January 17, 2013 13:44

January 9, 2013

Research Gems: "Battleground Adventures" by Clifton Johnson, 1915

Faithfulness to the truth of history involves far more than research, however patient and scrupulous, into special facts. The narrator must seek to imbue himself with the life and spirit of the time.

― Francis Parkman Jr.

As a historian and writer I often feel like a miner of sorts. I am digging for information, for details and interesting stories. Most of all I am searching for eye-witness accounts. When I find some wonderful nuggets I call them the gems of my research.

One of the great finds during this recent project studying Gettysburg was a digitized copy of a long forgotten book from 1915 called (of all things) Battleground Adventures: The True Stories of Dwellers on the Scenes of Conflict in Some of the Most Notable Battles of the Civil War. That is quite a title isn't it?

Inside, however, was treasure... the author Clifton Johnson traveled around to the major battlefields of the Civil War in about 1912 or so, and interviewed residents who had witnessed the fighting. There were six interviews with people from Gettysburg. The author kept the identities of his subjects anonymous. They were identified only as, "The Carriage Maker's Boy" or "The Bank Clerk."

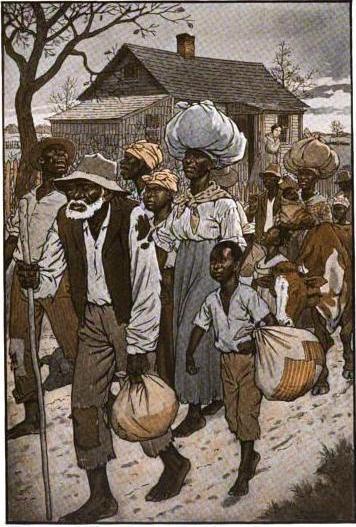

Two of them, however, were African Americans voices: "The Colored Farm Hand" and "The Colored Servant Maid." This was significant because, as one might suspect, there is not a lot written by African American writers of that time who were at Gettysburg in 1863. Yet both, however interesting, were too colloquial; their stories not tied to the narrative of the battle I was really after. Two of the other accounts, however, "The Bank Clerk" and "The School Teacher" both documented African Americans fleeing Gettysburg as Lee's army approached. In my mind they are some of the most valuable accounts because it was the perfect way to introduce the issue of slavery into the narrative of the new book.

African American refugees fleeing Gettysburg.

African American refugees fleeing Gettysburg.

Even more interesting... one of the chapters was entitled, "The Schoolteacher." It captivated me because one of the accounts I was studying was the diary of Elizabeth Salome “Sallie” Meyers who was a twenty-one-year-old schoolteacher in 1863. Could they be one and the same?

Elizabeth Salome “Sallie” Meyers

Elizabeth Salome “Sallie” Meyers