Lani Leary's Blog, page 3

July 28, 2012

After Death Communication

There is a body of research about the continuing presence of deceased loved ones, termed After Death Communication (ADC). The consensus of the literature is that the different forms of communication and contact are profoundly comforting and reassuring to the bereaved.

ADCs include intuiting the presence of the deceased, awareness of a touch, smelling a scent, hearing a voice, having a vivid dream, and/or seeing the deceased. It is estimated that over fifty million people have had such an experience, but many are hesitant to share these reconnections for fear of judgment and misunderstanding. Statistics can be a powerful source of confirmation, but individuals who have experienced the dream that is beyond vivid, or have heard the comfort of words from their deceased loved are convinced that their experience was real and not a hallucination. The sense of peace and comfort from these spontaneous connections happen at any time during or after death, and have been reported immediately or years after a death.

The more we openly discuss and share these experiences, the more we will come to accept the extraordinary as ordinary and normal. As with the subject of death, when we bring it out of the closet and into the light, we remove the stigma, myths, and fears surrounding the subject. We open ourselves to lessons that enhance our ability to live in the world. It is important to explore the phenomenon primarily because when discussed, it allows our grief to be expressed in healthy ways and transformed. We come to find new meaning in our loss, and gain comfort in a different, but on-going, relationship with the deceased.

The messages may be unique and the meaning is personal, but there is general consensus that the over-arching purpose of the message is to comfort and reassure. Many report that the “take-away” message was that there is a grander meaning to life beyond what we know when we are alive. The interpretation that their loved ones continue to be with them in spirit, and that they will one day be reunited is a powerful remedy to the feelings of hopelessness and abandon in grief. The verbal or non-verbal communications are received to mean “I’m okay”; “I’m with you”; “I love you”; “Everything is fine”; and “I will see you again”.

ADCs are the single-most important intervention that relieves the suffering of grief. The literature and my own research with the bereaved whose children, parents, spouses, siblings, and friends have died concludes that these communications must be shared, validated, and utilized in grief work. The ADC experience can change the painful intensity and duration of one’s grief into a softer acceptance of change. In other words, the communication from the deceased and its meaning to the bereaved transforms suffering into healing.

Louis LaGrand, Ph.D. suggests that the experience helps the bereaved accept the loss and re-invest in life. His book Love Lives On: Learning from Extraordinary Encounters of the Bereaved compiles evidence of how the communication can change one’s perspective and grieving process. Bill Guggenheim & Judy Guggenheim share their seven years of research with more than 2,000 people in Hello from Heaven. The stories shared are broad, diverse, and reach across age, gender, and ethnicity.

These experiences and the stories shared are a valuable, instructive guidance that can help us all cope with the painful physical and emotional reactions to the separation from loved ones. The profound change in one’s fear of death, anguish from separation, and ability to re-invest in their life needs to be part of our discussions about death, dying, and grief. To be open to different experiences can enrich our lives, and guide us through the universal experience of losing a loved one.

Pick up that figurative phone when you sense your loved one trying to contact you. Pay attention, stay open to the extraordinary, and honor your experience. Let me know if you have received contact from a deceased love one, and how it has affected your grief.

July 11, 2012

Speaking to Meria on the Meria Heller Show

Just had a wonderful experience sharing with Heller on her radio show. Join us via the link https://www.yousendit.com/download/Ql....

June 1, 2012

Lani Leary on Portland’s AM Northwest morning show

I had the exciting opportunity to appear on Portland, Oregon’s AM Northwest TV show yesterday to discuss my new book and the three things we can do for those in our life that are dying. You can see my appearance by clicking here to visit AM Northwest’s website.

April 12, 2012

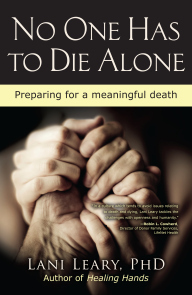

My new book “No One Has to Die Alone” is now available

My new book No One Has To Die Alone is now available! You can find it online at Beyond Words, Powell’s Books, Barnes & Noble or Amazon.com. You can also read the first chapter for free on my website.

The experience of caring for a loved one through terminal illness and eventual loss can be incredibly isolating and emotionally overwhelming. No One Has To Die Alone offers accessible insights, practical tools, and personal stories to provide a sense of community, profound relief, and deep meaning for both caregiver and patient through illness, death, and bereavement.

The first half of No One Has To Die Alone focuses on caregiving, while the second half focuses on the grieving process, including an entire chapter on how to compassionately support the unique needs of children through the grieving process. Each chapter is written to stand alone, allowing readers to reference any chapter and apply that information to their unique challenge.

See what others are saying on my book reviews page.

April 2, 2012

Moments of healing from moments of peace

I was privileged to be with a woman dying of leukemia, whose bone marrow transplant was unsuccessful. More painful than the weeks in the isolation unit, losing her hair, and the transplant itself was her desperate struggle to feel loved by her broken family. Throughout her short life she had been abandoned by an alcoholic mother, abused by an angry father, and humiliated by grandparents. In her last months, knowing that the transplant was unsuccessful and the leukemia kept feeding on her body, she fought her hardest battle to make peace with her family and ask for what she needed.

Carla’s father responded by traveling to the Cancer Center to be with her for her transplant. But, she said, he was only with her physically, and she felt the old sting of separation and alienation from the man from whom she most wanted to feel love. And gradually, her determination and fight soured into anger and resentment. She looked like a red roaring flame of rage, and her tone of voice hissed like a coiled snake. The nursing staff confronted her, avoided her, and told me they felt drained after working with her. Carla told me she wanted to shrivel up and die. She said she felt like an old prune without any juice left.

I held out my cupped hands and asked her if she would allow me to keep her hope and her love for her in a safe place. “I will keep it in a chamber of my heart, under lock and key”, I told her. I would guard and nurture those energies, and she could have the hope and love back whenever she felt strong enough again to carry them herself. The hope and love were hers and I was merely holding her potential for healing, because, I told her, I believed in her timing, her process, and her own resources. She needed a guardian for her struggle, someone who would champion and encourage her when she felt like giving up, but wanted to go on. Carla needed an external mirror to remind her that she once experienced love and healing, and could again. She needed permission to feel disappointed. She needed a way to allow the energy of anger and resentment to spend itself dry without adding to her dis-ease.

It was a simple act of symbolic holding that I performed. Sometimes it is just a part of oneself that needs to be held, cradled, comforted, and protected. In Carla’s case, it was her healthy, hopeful, loving Self that needed a safe space. I created a visual image by cupping my hands, showing Carla where she could lay her hope and love, like a wounded child into a caretaker’s arms.

Weeks later Carla told me she felt she had made peace and that she felt strong enough to take back her hope and love. She told me that I had shown her a way to accept all the parts of herself, because I was willing to acknowledge and validate her rage. Once validated rather than judged, she could spend time trying to understand and work with her feelings. She did not feel that she could have attended to the work of understanding her rage, if she had been worried about the “good” parts of her, the hope and love, being harmed.

Carla died soon afterwards. When I think of Carla now, I remember a snapshot of time as I held my cupped hands towards her and she put both her hands in mine. That moment was an act of faith in her own powers of resolution and healing, and in my ability to nurture and safeguard a precious part of her. And in the next instant I remember the moment when she asked for her hope and love back, and the courage that it must have taken to believe in and act from a position of peace. That moment of peace was also her moment of healing.

March 26, 2012

Death does not just happen to you

Everyone carries his or her own weight of grief. We each have a different story, perhaps with a different context. But grief is universal. We all experience the death of a family member. We all lose a loved one. Death does not visit you alone. It is helpful and comforting to remember that we are not singled out. We are not victims. This death is not a personal punishment against you. Death is universal. It did not happen just to you.

Someone once wrote that how we handle our deepest wounds is the equivalent of how we will approach our dying. We can accept our death and the death of a loved one, by searching for growth, meaning, and transformation; or we can recoil, denying and angry about the inevitable, and miss the opportunity to stretch into our greatest potential. It is a choice. You can make life and death less difficult, and more peaceful. You can find the peace now, by finding meaning and using it in your life.

We make meaning in order to change the quality and our understanding of what has happened, the legacy of one’s life, and what is now possible for us going forward. It is not what happens to us that matters, but how we come to make sense of what happened that predicts our emotional health and future. We tell stories to bring what is inside of us to the outside, so that we understand the meaning of events. In this way, telling the story of our loss over and over is how we create a more positive, healthy understanding from a potential tragedy. If we can make sense of our pain, we can change.

We make meaning in order to construct how we will remember our loved one, and how we will remember our relationship with that person. We make meaning to change the events that are remembered, how it is remembered, and with what or whom those memories will be associated. The meanings that we attach to the event of the illness, dying process, or dying moment will color how we live in the world and in the future.

We can help mourners by encouraging them to tell their story over and over. Every time a memory is reviewed, the intensity of suffering has the potential to be softened. Recent research suggests that memory is “plastic” and that each time we bring a memory to mind we may alter it in some way. Our story may change over time as our understanding changes. How we perceive the events, understand the context and the connections, and how we articulate the narrative changes. Research and interventions used in therapeutic settings for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, show that exposure and recalling traumatic events, such as the death of a loved one, does not erase a memory but can change the quality of the memory. The memory becomes weaker, and has less of a hold and negative impact on the survivor. Telling our story and finding meaning keeps us from living in the past.

What is mentionable becomes manageable .

March 23, 2012

My new book reviewed by Publishers Weekly

This is kind of huge for me. It’s a big deal that Publishers Weekly reviews a book, and their weekly review of new books just came out…including mine! Here it is:

Leary, a psychotherapist and professor of death studies, has written an extraordinarily clear-eyed and helpful guide for those who must care for a dying loved one, an almost unavoidable and challenging situation. Leary brings both the personal experience of her parents’ deaths—two very different situations at different times in her life—as well as two and a half decades’ professional experience working with the dying and the bereaved. Caregivers almost always begin the journey of caregiving not knowing what to do or say; Leary offers both information and comfort for them. Half the book deals with caregiving for the dying, and the second part concerns itself with the bereavement process; several appendixes list varieties of resources. Leary respects both the patterns within and the uniqueness of the processes of letting go and grieving. She provides a public service; this book is strongly recommended for libraries. (Apr.) (via Publishers Weekly)

My book No One Has to Die Alone: Preparing for a Meaningful Death is available April 10th. You can read more about it and pre-order your copy on the “her new book” page of this website.

March 19, 2012

The key to resolving grief

The key to resolving grief is the feeling of acceptance that comes through validation. To resolve means to settle, to work out, or to find meaning. It does not mean to erase, or to end. Grief does not end, but grief is transformed. Grief can soften. It can be accepted. It can take on another shape, rather than taking over a person’s life. One can carry grief differently after working through grief and finding resolution. But grief does not end.

The great healer of our grief is validation, not time. All grief needs to be blessed. In order to be blessed, it must be heard. Someone must be present, someone who is willing to “hold” it by listening without judgment or comparison.

Those who grieve need both verbal and non-verbal permission to feel whatever feelings arise during grief. Their personal way of experiencing their loss should be given consent and validation. The ways they “know” their grief should be honored. Mourners need to be encouraged to express their grief in ways that are most comfortable for them, through words, tears, song, art, movement, or activity.

While grieving, those in pain need a sense of a compassionate presence. That is a person who provides a healthy relationship and companions them. It is the person who can “just be” with them in whatever way is helpful throughout the journey. There may be several people who support with their ability to be present, and each may offer different aspects that are needed. The bereaved need:

To be cared for with your presence, permission, patience, predictability, and perseverance.

To have their feelings acknowledged and their loved one remembered.

To have their feelings and needs normalized.

To be heard.

To be seen and acknowledged.

February 4, 2012

How to Help a Child Understand Death

Ask your child direct, simple questions that focus on full understanding of the event and the ramifications.

Respond to what they do and do not understand.

Use everyday living experiences and “teaching moments” to discuss the reality that has happened.

Answer questions when the child asks. Answer simply and honestly rather than protecting the child from a “harsh reality” and evade the truth. Answer the same questions repeatedly if asked, with patience; your child is processing and weaving together complex concepts that require repetition and context.

Temper and adjust your response and answers to reflect the child’s age, experience, maturity, and capacity for emotion and facts.

Answer the question that is asked; do not overwhelm with detail, but ask what she heard and now understands.

Give the child time alone to reflect.

Provide opportunities and experiences for the child to show you what he or she understands or is confused about reglarding illness, death, and dying. Activities including movies, art, music, writing, or play acting can all provide feedback about how the child is processing information.

January 30, 2012

Children need help understanding illness, dying, and death

Children need help understanding illness, dying, and death. Forty percent of all children will experience at least one traumatic event before they become adults. Death, loss, and trauma are common experiences for children, but the challenge is usually not addressed until after the crisis has occurred. Let’s not give children a crash course in grief! The opportunities for growth embedded within any crises are too important to leave as after-thoughts. The ramifications to our children of not having the skills or support to deal with personal change of this magnitude are dangerous. As adults and caregivers, we need to discuss the inevitability of loss, and teach coping skills before they are needed, and during a time that is not so emotionally volatile. Children need help if they are to navigate and successfully adjust to circumstances they do not understand and for which they have not developed skills.

This means using appropriate vocabulary and find “teachable moments” to talk about the reality of living things decaying and dying. There are opportunities every day, all around us, to point out the inevitability and universality of death. All living things die.

We can model and show our children how to respond to loss. Show your child that tears are normal and acceptable. Give them the language to talk about their feelings, and let them listen to you as you share your reactions and response to the loss of a job, a dream, a friend, a move to a new home.

From the beginning of my daughter’s life, I invited her to be with me as I cried about a death saying, “I’m sad and I’m okay. It’s okay to be sad.” It is an important lesson to show children that one can feel sad/angry/confused while still feeling safe and whole. To share and show a child that “this too shall pass” is to give them a roadmap through challenge.

Lani Leary's Blog

- Lani Leary's profile

- 1 follower