John Janaro's Blog, page 273

August 6, 2014

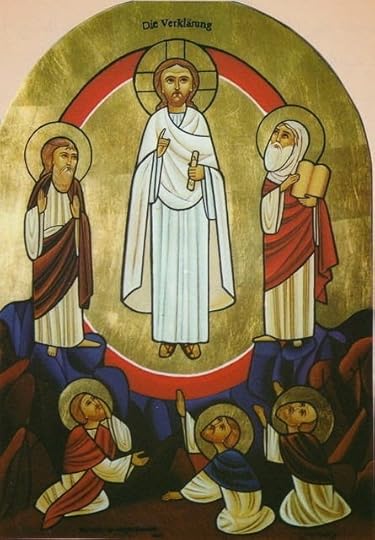

Transfiguration

"A bright cloud cast a shadow over them,

then from the cloud came a voice that said,

'This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased;

listen to him'" (Matthew 17:5).

May "his grace transforms us into his image, so that living in the spirit of the beatitudes we are light and consolation to our brothers" (Pope Francis, August 6, 2014).

TRANSFIGURATION icon by nuns of St. Damiana Monastery, Egypt.

TRANSFIGURATION icon by nuns of St. Damiana Monastery, Egypt.

then from the cloud came a voice that said,

'This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased;

listen to him'" (Matthew 17:5).

May "his grace transforms us into his image, so that living in the spirit of the beatitudes we are light and consolation to our brothers" (Pope Francis, August 6, 2014).

TRANSFIGURATION icon by nuns of St. Damiana Monastery, Egypt.

TRANSFIGURATION icon by nuns of St. Damiana Monastery, Egypt.

Published on August 06, 2014 19:00

August 4, 2014

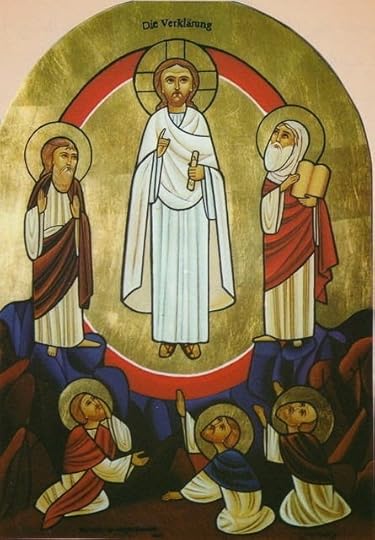

The Lamps Go Out in Great Britain

Today was a remarkable day of remembrance all across the United Kingdom. After evening vigils, lights were turned off in public places and all were encouraged to observe the hour before 11:00 PM GMT by turning off all lights and leaving only a single lamp or candle burning.

Today was a remarkable day of remembrance all across the United Kingdom. After evening vigils, lights were turned off in public places and all were encouraged to observe the hour before 11:00 PM GMT by turning off all lights and leaving only a single lamp or candle burning.100 year ago today, on August 4, 1914, Great Britain declared war against Germany. The previous day, foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey gave his famous speech to the House of Commons revealing England's attitude toward the war on the Continent. His memorable and symbolically prophetic words were the motive of today's observance, when he said, "The lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our lifetime."

There had been hope that England might maintain neutrality, as statesmen in London and Berlin worked right until the end attempting to reach a settlement regarding the status of Belgium. The British government insisted on upholding the 1839 treaty guaranteeing Belgian neutrality, while the Germans insisted that they had no interest in Belgian territory, but that their own (preemptive) defense (strategy) required their troops to pass through Belgium to head off the French before the Russians mobilized. German chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg expressed his amazement to the British ambassador that his country was ready to go to war "over a scrap of paper."

The two modern empires had been struggling to find some mode of peaceful coexistence in the first years of the twentieth century even as they sought strategic advantages and economic dominance in European and world trade and manufacturing. Belgian neutrality became England's war cry, though Grey had made it clear in his speech that British interests could not endure a German victory on the Continent. Meanwhile the war party in Berlin, having already used duplicity to egg on the Austrians and light the fires in the East, would now have their way by driving an unconscionably ruthless and destructive path through Belgium.

The two modern empires had been struggling to find some mode of peaceful coexistence in the first years of the twentieth century even as they sought strategic advantages and economic dominance in European and world trade and manufacturing. Belgian neutrality became England's war cry, though Grey had made it clear in his speech that British interests could not endure a German victory on the Continent. Meanwhile the war party in Berlin, having already used duplicity to egg on the Austrians and light the fires in the East, would now have their way by driving an unconscionably ruthless and destructive path through Belgium.On the morning of August 5, 1914, England awoke and found herself at war. The players on the field were now complete, and the monstrous game was on.

"Please God it may soon be over," King George V wrote in his diary. Many of the English, convinced that the war would be over by Christmas, rushed to the recruitment offices to volunteer lest they miss their chance for battlefield glory. How terribly wrong they were in their expectations of brevity and of glory.

Indeed, the awful, impossible game was on.

Published on August 04, 2014 18:50

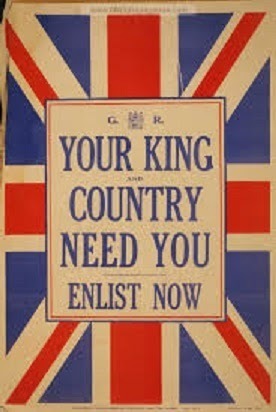

August 1, 2014

The War of the World

August 1, 1914. 7:30 PM. Germany declares war on Russia.

August 1, 1914. 7:30 PM. Germany declares war on Russia.Both armies are mobilizing, bringing weapons to the field that are exponentially more powerful and more ruthless than anything before in human history.

It was clear that this was a momentous step, unleashing a catastrophic war in Europe. They knew it would be terrible when it began, but they did not know the dimensions of the horror that was being unleashed.

Armies of volunteers and conscripts poured into the field (and soon, the trenches) over the next four years, and massacred one another by the millions for reasons none of them really understood.

Terrible battles lay ahead, in which hundreds of thousands on both sides would be slaughtered, with no purpose being achieved, no ground taken, no advance, no retreat, nothing. The soldier who fell was anonymous, and his dead body would be replaced by another and another and another....

This conflict would bring the dehumanization of war to a new level, and would sow poisonous seeds of discouragement in the hearts of people in Europe and the West. The Great War raised the dramatic question of that last century: "Does the life of the individual human person have value for its own sake? Or is it merely part of a mass of humanity that is manipulated by those in power?"

This is still the urgent question for us today.

Published on August 01, 2014 19:57

July 30, 2014

A Prayer at Day's End

Lord give us all good sleep

and heal the wounds of this day.

Refresh our spirits

and let us awake

to praise You in the freshness

of tomorrow's youth.

One day is enough for us.

One day's troubles suffice for our strength,

for we are small and weak

and wilt with the coming of night.

More than the span of a day

is beyond our power.

So take us, Lord, into Your Heart

and let us know the promise

of Your rest.

and heal the wounds of this day.

Refresh our spirits

and let us awake

to praise You in the freshness

of tomorrow's youth.

One day is enough for us.

One day's troubles suffice for our strength,

for we are small and weak

and wilt with the coming of night.

More than the span of a day

is beyond our power.

So take us, Lord, into Your Heart

and let us know the promise

of Your rest.

Published on July 30, 2014 18:30

July 28, 2014

"I Ask With All My Heart: STOP! PLEASE!"

When he gave his message yesterday after the Angelus, Pope Francis remembered that today is the 100th anniversary of the beginning of World War I. As he addressed the current conflicts in the world of the 21st century -- especially those in Ukraine, Iraq, and Israel/Palestine -- the Pope pleaded for us to remember the past and learn the lessons of history.

Those lessons pertain primarily to the devastation of war that can arise so quickly when human passions triumph over reason and love. The effort to resolve differences by what he calls "courageous dialogue" is a process that must be taken up again and again, and carried through with perseverance.

"May God give the people and their leaders the wisdom and strength to carry along the path of peace with determination, resolving all disagreements with the tenacity of dialogue.... I hope the mistakes of the past will not be repeated."

"Let us remember that all is lost when there is war but nothing is lost when there is peace. Brothers and sisters: no more war, no more war. I think above all of the children, whose hope of a respectable life and of a future are wrenched away from them; dead children, mutilated children, children who play with remnants of the war instead of toys. Please stop, I ask you this with all my heart, stop, please" (Pope Francis, Angelus, July 27, 2014).

"I ask you this with all my heart: STOP! PLEASE!"

Why is the Pope pleading for peace on this day?

Why is the Pope pleading for peace on this day?World War I was the beginning of a terrible lesson for humanity regarding the monstrous destructive possibilities of technological power. The ever greater possession of such power today corresponds to an urgent responsibility for us to become peacemakers: as individuals and communities, peoples and political entities. Francis's passionate words -- "No more war! No more war!" -- merely echo the tremendous plea of Paul VI before the United Nations on October 4, 1965: "Jamais plus la guerre!" (War never again!)

The Popes of recent times do not intend to establish pacifism as an absolute moral principle. We know that the Catechism (see, e.g., ##2302-2317) recognizes the justice of legitimate and proportionately restrained defense, and honors those who serve their countries and humanity -- those who stand ready to defend innocent, vulnerable people against violence and aggression. The Popes are not promoting an ideology of "pacifism." They are praying for something very concrete, a real peace based on the common effort for justice, solidarity, mutual understanding, restraint, and love.

In a world of globalized interdependence and unprecedented power, peace is imperative. Human beings must not look to war as a means of resolving conflicts or securing their own selfish interests. Too often, war has been "politics by other means." This has always been wrong, but the 20th century has taught us how horribly wrong it can be. We must be vigilant, because this horror begins within our own hearts, and today more than ever we possess the power to externalize our own violence in a way that brings catastrophe and unimaginable misery to whole peoples, and possibly the whole world. If we are to be peacemakers, we must grow in vigilance and responsibility.

But have we grown? Is the human race more vigilant and more responsible today than the people of a hundred years ago who initiated and cooperated in an explosive nightmare? No one wanted "the Great War" in 1914. It was pride and fear that sparked it, and stubbornness that kept it going after it had spiraled out of control beyond everyone's wildest imagination.

What happened a hundred years ago today? When we look at the events, we recognize a certain familiarity. We have these same kinds of struggles today, in different contexts. We have local tensions between peoples in specific places. We have great powers with complex interests, who want to control spheres of influence. We are afraid of one another. Have we learned anything?

What happened? Tensions in Central Europe between Serbia and the Austro-

What happened? Tensions in Central Europe between Serbia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire rapidly escalated to the war declared by Austria at dawn, July 28, 1914.

Europeans still hoped that the conflict might be contained. Perhaps this would be "just another war in the Balkans." But as soon as the shooting began, the gravity of the danger became evident. Standing behind Serbia was the Russian Empire. The Tsar was under pressure from revolutionary movements and divisions within his own government. Russia's strong stand would unite the nation... though it would only be for the short term. Meanwhile the crumbling Hapsburg Empire, seemingly unable to adapt its traditional multinational organism to the exigencies of the 20th century, could not have shaken the rest of Europe on its own. But their neighbor had found success in establishing a powerful and prosperous nation-state. Germany felt strong, but also new, and nervous. They were uncertain about the growing strength of the French on their Western border and the Russians on the Eastern border. The German government and military command would decide that their alliance with Austria and a looming confrontation with Russia represented an ideal pretext for them to establish their own security by a preemptive war against their competitors on both borders. But then there was Belgium, and England's promise to protect Belgian neutrality....

On July 28, however, there was still hope for containing the conflict that had just broken out. There was hope for mediation, for mutual understanding between the parties. It would not have been easy to reach this understanding, and it is foolish to be naive about it. Nothing is more difficult that dialogue and reconciliation, which has to build step by step. It requires tenacity and a kind of inner heroism that perhaps has not yet been seen in the political sphere. It is a heroism we need very much.

Today, a hundred years later, there is still hope. Let us be vigilant. Let us pray for heroes to arise in our midst. Let us pray that we might become heroes, peacemakers, sons and daughters of God.

Published on July 28, 2014 18:36

July 24, 2014

The News: How Can I Know What to Worry About?

Tensions, conflicts, disagreements, arguments, violence, destruction. I find it every morning when I read the news on the Internet. July 24, 2014 is full of such stories, with details of facts, unconfirmed rumors, analysis, predictions, hopes, fears.

In more than thirty years of reading/watching the news, I have seen many "decisive moments" that were unimaginable and inconceivable before they suddenly happened. (Only in retrospect could we trace the lines building up to these moments.)

I've also seen huge amounts of attention and analysis poured out over events that never rose to their expected significance. Other issues have built up slowly over the years, and I know from the study of history that great changes often happen gradually, without drawing much attention to themselves.

Still, these times we live in today -- with so much admirable achievement and so much dissipation and chaos -- seem to point to the inevitability of a shattering conflict. Yet rarely has there been an age in history when thoughtful people haven't had expectations of imminent perils arising out of what has always been called "the evil of the times."

Human history is always ambivalent, because the human heart is ambivalent. As Solzhenitsyn says, "the line between good and evil passes through the human heart." We so often look at the day's events and wonder, "When is the great crisis coming?"

We don't know where events are leading. All of us have the responsibility, in different ways, to be attentive to our environment and our circumstances and seek to foster the good as much as we can, even as we work for victories of goodness within ourselves.

Still, there is so much that is beyond our control.

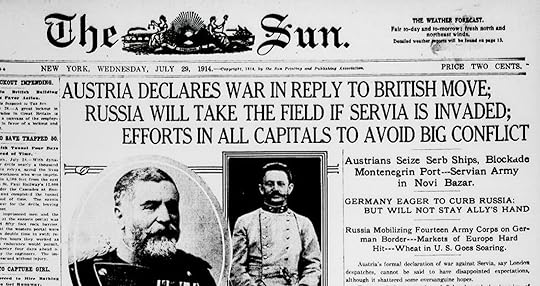

Allow me for a moment to use a homey, "old media" analogy: I could have read the newspaper today. Read about more escalation in Ukraine, more Gaza, more "Islamic State," more suffering, more refugees. But my newspaper would not come with red markings indicating that here is the big story. Here is the story that signals the beginning of the end of an epoch, a gigantic catastrophe, a great crisis that is apocalyptic at least in the sense that a world (if not the world) is coming to an end.

There are no red markings in the paper today that say, "a hundred years from now, this is what everyone will remember." It's eerie, reading the archives of the London Daily Telegraph from a hundred years ago, from July 24, 1914. Seven columns on every page packed with the news of the times. An English reader would not have guessed that the kerfuffle in Central Europe was about to put his nation at war with the Dual Monarchy and Germany, that a generation of Europe would be hurled into an abyss, that a world that began with the imperial ideal of Rome was entering its final days.

The English reader could not have known this, nor could he have done anything about it. However, he might have been very nervous about a growing confrontation that was the urgent talk of that day. Irish "Home Rule" had finally been granted by Parliament, but the controversy only seemed to grow. The Protestants of Ulster were furious, while Irish nationalists were not ready to trust what would have been "Dominion" status right under England's shadow and still opposed by powerful opposition in the English Parliament.

The page above notes the continued growth of opposition militias, the Ulster Volunteers and the Irish Volunteers. There was talk of civil war in Ireland, and in the next couple of days there would even be skirmishes. Ironically, both militias turned to Germany to purchase arms.

But then came the Great War. Home Rule was suspended and the men from both militias joined up with the rest of Great Britain's fighting generation to face a new and unexpected enemy. Only a few of the most radical of the Irish republican volunteers refused to join with the British army. They remained behind, apparently insignificant in 1914. However, their moment would come. Ireland would have civil war, independence, and continued conflict in the North that would still be writing headlines at the end of the century, and that today holds together only by a fragile peace.

Thus, the decisive moments of history continue to unfold, and our times are not different insofar as the struggle between good and evil continues in the world and in the daily challenges that our hearts face.

Only at the end will we see everything, at the true decisive moment -- a moment that is already ours in hope -- a moment when the world and all hearts will pass through the fires of Mercy.

Published on July 24, 2014 20:55

July 22, 2014

It's Not a Smiley Face

No, this is not a cyclops with a smiley face.

If only this sad similarity could make it so. What is this thing? It looks "familiar," in a way, as if it were just another instance of graffiti on a wall. Out of its context, there is little about this cartoonish marking that would cause us to suspect the sinister intent behind it.

This is the letter nun in the Arabic alphabet, corresponding to the Western letter "N" -- in standard typography it looks like this:

Thus we have an "N" with a circle around it, spray-painted on a wall. The circle with the letter nun, however, is found on walls and doors all over a town in the Middle East. The town is Mosul, in the province of Nineveh, in a country that -- for now, at least -- still bears the name of "Iraq."

The "N" stands for Nasara. Nazarene. It marks the dwelling places and the property of "the Nazarenes." This is a derogatory Muslim term for those who follow "the Nazarene," the man from Nazareth.

Jesus of Nazareth.

A violent Islamic jihad organization that styles itself (most recently) as "the Islamic State" is marching toward Baghdad. There they hope to realize the bizarre and destructive fantasy of restoring the Islamic Empire. There is a grim, grey bearded lunatic among them who has already proclaimed himself Caliph.

The I.S. is a revolutionary force born from the tumult in Syria. Their success in Iraq is due primarily to alliances with disaffected Sunnis who feel oppressed by the Shiite dominated government in Baghdad, and to the incoherence of the Shiite government, which has accomplished little beyond oppressing the Sunnis.

The world groans at these wars that won't go away. A passenger airline shot down over Ukraine. Israel and Gaza. And this too; what is one to make of it? Iraq is falling apart, and Kurdistan is beginning to look like the safest place in the region.

But there is a deeper violence at work here. The Islamic State gave the followers of the Nazarene an ultimatum: Convert to Islam, pay a crippling "religion tax," go into exile, or be put to death.

The "N" marks the property of Christians. It indicates, ironically, that this property no longer belongs to them.

In fact, the Chaldean Christians have been in this region since the time of Jesus of Nazareth. They are the ancient inhabitants of this region, the children of Abraham's cousins. They have remained distinct from the Arabs who conquered them in the first millennium, but they have lived with them. Along with other ancient Christian communities, they have contributed to the formation of complex societies in the lands of Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq (and also Egypt). These societies built up centuries of religious tolerance.

But these societies could not endure the political exigencies of globalization. It is an atmosphere where radicals flourish, and ancient peoples are worn down relentlessly.

The West has experienced terrorism at the hands of radical jihadists. Chaldean Christians, however, are being subjected to the horror of genocide.

The mad Caliphate is not likely to last, but it may last long enough to finish the work of dispersing and destroying the heritage of one of the world's most ancient communities. The Christians of Mosul have fled to Kurdistan. Their churches are being burned.

The Mass is no longer offered in Mosul. The people who have given continuous witness in the land of Abraham to Him who is the son of Abraham are perhaps finishing the long journey into exile that began a decade ago, when radical groups emerged following the downfall of the secular dictatorship.

We must pray and make sacrifices for our suffering brothers and sisters. We must remember them. We must embrace them in our hearts, in solidarity.

We pray, above all, that their faith will endure. A heritage may pass away. A people may disappear from history. But they will rise again, by the power of the One who dies no more, over whom death has no power. Because the Man from Nazareth is risen from the dead.

Published on July 22, 2014 21:44

July 18, 2014

The Brothers Janaro

Left: Walter and John Janaro (with Santa), around 1967. Right: At Dean's Steakhouse, around 2013. People say we have

Left: Walter and John Janaro (with Santa), around 1967. Right: At Dean's Steakhouse, around 2013. People say we havethe same facial expressions in these two pictures. I think they may be right! But we definitely have different hairstyles. :)

Happy Birthday to my older brother, Walter Janaro!

I'm sure he doesn't want to appear on this blog, but I'm also sure that my two biggest and most faithful readers (our parents!) would enjoy these two photographs that span most of the years of our lives. And indeed it has been a special blessing that, for the great majority of those years, we've lived near each other.

Reading with Jojo and TeresaThese day's he's known around our house as "Uncle Walter," and he belongs so much to our family that it's hard to imagine our life without him. I know that it is a real grace to have a brother who is a person of faith, who is close to me and who more than gets along with Eileen and the family. He is my only sibling, and his personality is very different from mine in many ways, although we also have much in common too. The strongest bond between us, however, is our faith in Jesus and our commitment to Him in the life of the Church.

Reading with Jojo and TeresaThese day's he's known around our house as "Uncle Walter," and he belongs so much to our family that it's hard to imagine our life without him. I know that it is a real grace to have a brother who is a person of faith, who is close to me and who more than gets along with Eileen and the family. He is my only sibling, and his personality is very different from mine in many ways, although we also have much in common too. The strongest bond between us, however, is our faith in Jesus and our commitment to Him in the life of the Church.My brother has always been a man with an amazing capacity for friendship. For many years, he has been a mentor for college students (he is the registrar at Christendom College), and also for high school kids in his CCD class, and for all sorts of people who pass through this little part of the world -- friends of friends, family members of students, neighbors, people from the parish, and from many other places.

This genial and loyal man has a great memory and a great heart for all the people he has known. College alumni have grown up and sent their kids to school, knowing that Walter would be there to make them feel at home. Walter has never married, but I think he finds himself called to play the special role that he plays in the lives of so many other people.

He has been a great friend to me, always a source of help, a voice for common sense, a loving brother. Thank God for him. Ad Multos Annos!

Published on July 18, 2014 10:03

July 16, 2014

July 16, 1914: THE ULTIMA RATIO

One hundred years ago, July 16, 1914, there was lots of important news in the London Daily Telegraph (which cost one penny).

One hundred years ago, July 16, 1914, there was lots of important news in the London Daily Telegraph (which cost one penny).After a couple of pages of stock and banking figures we arrive at the big news of the day: the scandalous divorce trial of an actress known as Queenie Merrill. Meanwhile, Parliament is buzzing about election reform, budgets, and what is clearly Britain's most pressing political problem: "Irish home rule." An advertisement for skin creme assures us that "it is justifiable for every lady to regularly use" to "render herself more attractive and her skin more lovely." There is much excitement over an upcoming international boxing match. Theatre listings are on page 10. More articles on page 11. Seven tight columns of this and that. Foreign news. Parliamentary debt. Ulster again.

What's this?

Next to a column on the formation of a new society for musical composers we have news of some sharp remarks from the Premier of the lower house of the Hungarian Parliament. "Austria-Hungary's relations with Servia [Serbia] must be made clear." There were reports of Bosnian revolutionary agitation (although "the reports turned out to be baseless") and reported fears for the safety of Imperial citizens in Belgrade; he had asked the Serbian government to insure their safety with appropriate "precautionary measures."

Clearly, the six paragraph article conveys some significant stress way over there in Continental Europe. There has been "agitation" in the region for the past two weeks, ever since a Serbian terrorist (possibly linked to elements of the Serbian government) assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

This is serious business; any unrest "must be repressed with the utmost energy." However, it doesn't appear that the good Count Tisza wanted anyone to worry at this point. He assured the House that "the responsible authorities were fully conscious of the interests bound up with the maintenance of peace."

Nevertheless, the Premier wanted to make sure not to rule out what might become necessary as the LAST RESORT in the clarification of things. He said that "the State that did not consider war as the ultima ratio could not call itself a State."

After this statement -- the London Daily Telegraph of July 16, 1914 informs us -- the Hungarian Assembly broke out in cheers.

Two weeks and five days later, Britain declared war on Germany and Austria-Hungary, joining in alliance with France and Russia. World War I was about to begin. History was about to go totally off the rails, but I wouldn't have known it from reading the newspaper from 100 years ago today.

Published on July 16, 2014 19:35

July 15, 2014

Saint Bonaventure Shows Us How It's Done

"He, therefore, who is not illumined by such great splendor of created things is blind; he who is not awakened by such great clamor is deaf; he who does not praise God because of all these effects is dumb; he who does not note the First Principle from such great signs is foolish. Open your eyes therefore, prick up your spiritual ears, open your lips, and apply your heart, that you may see your God in all creatures, may hear Him, praise Him, love and adore Him, magnify and honor Him" (Saint Bonaventure, The Journey of the Mind to God I:15).

"He, therefore, who is not illumined by such great splendor of created things is blind; he who is not awakened by such great clamor is deaf; he who does not praise God because of all these effects is dumb; he who does not note the First Principle from such great signs is foolish. Open your eyes therefore, prick up your spiritual ears, open your lips, and apply your heart, that you may see your God in all creatures, may hear Him, praise Him, love and adore Him, magnify and honor Him" (Saint Bonaventure, The Journey of the Mind to God I:15).As has become my habit, I have celebrated the feast of St. Bonaventure by "doing some theology." Or rather, to put it more simply, I have read, pondered, and written a bit, and I will offer a few ramblings here.

When reading St. Bonaventure, I am inspired by his meditations, in which the mystery of the Trinity is found everywhere, and the origin and destiny of all things resonate deeply. Bonaventure's Journey of the Mind to God is full of illumination until the point of the final abandonment of self in an ecstasy of love that leaves everything "behind," even the understanding. It is the darkness of losing one's self, of being conformed to the Cross of Jesus.

I also read with all the proper interest -- and all the strange, ambivalent instincts -- of the professional theologian. I am perplexed by Bonaventure's philosophical anthropology, where Augustine, Anselm, and Aristotle all meet and mix. The presence of God to the soul (and therefore to the intelligence) appears to be the presupposition for all knowledge. Yet this is not ontologism, surely. This is something else: something like Augustinian divine illumination and Anselmian apriori certainty of God, combined to serve as the light that bathes the mind and everything else with a wisdom that grows brighter and brighter for those who seek it. St. Bonaventure is describing how a human mind redeemed by Jesus and following Jesus experiences reality. He is describing how he experiences reality.

Nevertheless, the Seraphic Doctor is practitioner of the medieval scholastic method. He speaks with the ordered discourse of the University of Paris. We can't resist the urge to "take him apart," and isolate theoretical presuppositions, and perhaps we're not entirely wrong in this effort. Is Bonaventure advocating a dynamic intellect with some sort of "a-priori" luminousness of Divine presence and action impelling the mind to go out to meet reality (and return to itself)?

Karl Rahner and young colleague Joseph

Karl Rahner and young colleague JosephRatzinger at Univ. of Munich, mid 1960sI can be forgiven, I think, if I find some affinity here with the epistemology of the enormously significant twentieth century German Catholic theologian Karl Rahner (1904-1984). I'm not the only one to compare Rahner with Bonaventure. Rahner appears to clarify how an approach like Bonaventure's can avoid ontologism by presenting this presence of God not as an innate object of knowledge, but as the (a-priori) condition of possibility for the knowledge of everything else. Rahner took in many directions his highly original effort to bring together classical Christian thought and modern philosophical approaches. His work was brilliant, yielding fascinating insights, opening new and fruitful perspectives, but also weighed down by an ambivalent project to rescue from itself the subjectivism of post-Kantian philosophy.

It has been argued (by, among others, his fellow German theologian Joseph Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI) that Rahner's intellectual system led him in the direction of certain theories and tendencies that gave priority to subjective experience over the objective encounter with Christ in the Church. The ultimate effect of Rahner's project on Catholic thought remains to be assessed, but in Europe and North America (at least) there hasn't been much to applaud so far (hashtag #Understatement).

Unlike many Rahnerians and post-Rahnerians, St. Bonaventure doesn't end up in a metaphorical cul-de-sac (or off a metaphorical cliff). Why is that? I think it's because Bonaventure didn't worry (the way we do) about "Bonaventurianism." He didn't care about his "thought;" he cared about Christ! He was attentive to his task: he preached the faith, he taught it, he pondered it... because he loved Jesus.

We may try to tease out Bonaventure's theory of knowledge, but we must remember that for him it was never a matter of bare epistemology; it was always part of the Christ-centered, graced and mystical journey of the soul to union with God. It was always about his journey to God. As Gilson points out, the context of mystical theology shapes all of Bonaventure's thinking. Hermeneutics are important.

A mystical hermeneutic may be what we need to draw out the profound and enduring insights of Karl Rahner, the fruits of his own attention to his task over forty years, and his own journey to God, his love for Christ and the Church, his sorrow for the great alienation of the human being in the twentieth century. He found it necessary to enter into the "dark night of the world," to preach that the love of God draws close to the human person in the darkness. People are obsessed with the things of the world, and yet these things fall short of their desire; these things say, "go beyond us" but people do not see anything in this "beyond" -- our society has buried God and left him in the past. What, then, is this abyss beyond all things?

Here Bonaventure might say that the darkness seems like nothingness because people have allowed themselves to forget God -- that they only fear "darkness" because it is an absence of the "light" that they (somehow) already "know" and therefore expect to find and want to possess forever. "Non-being is the privation of Being," Bonaventure says, and therefore "it cannot enter the intellect except through Being" (Journey V:3). As in Bonaventure's time, so also in ours, "when [the mind distracted by limited things] looks upon the light of the highest Being, it seems to see nothing, not understanding that darkness itself is the fullest illumination of the mind" (Journey V:4). Rahner would agree, and he sought ways to communicate this to people in a darkness deep and thick, an abyss that stretches beyond all of the unparalleled frenzy of dissatisfying activity and disorientation.

It is not my intention here to write an intellectual tribute to Karl Rahner, a theologian with whom I have significant disagreement, and about whom I've written and spoken with criticisms that I think are valid (even though they have not always been entirely fair to the complexity of his thinking). Rather, I am celebrating the feast of St. Bonaventure by studying and pondering this work we call "theology," a work that I have been called to lay aside for a time, for reasons that I do not understand but that I believe are good. In this darkness there is a light.

There is Jesus, who helps us by being present in the places where we seem to see nothing. He fills these places with His wounds.

For "one cannot enter into the heavenly Jerusalem through contemplation unless one enter through the blood of the Lamb as through a gate..., by the cry of prayer, which makes one groan with the murmuring of one's heart..., the cry of prayer through Christ crucified" (Journey Prologue:3-4).

Published on July 15, 2014 20:37