John Janaro's Blog, page 110

November 18, 2020

Thoughts on Family Life and "Apostolic Work"

Can you devote your life to serving the Lord and your neighbor, or more precisely, to a vocational path that focuses specifically on an "apostolate," on evangelization and/or works of mercy, while also being a husband and wife raising a family?

Can you devote your life to serving the Lord and your neighbor, or more precisely, to a vocational path that focuses specifically on an "apostolate," on evangelization and/or works of mercy, while also being a husband and wife raising a family? Yes, you can.

It's not an easy path, nor is it for everyone as a whole external format that determines daily work and other concrete life circumstances. Everyone can participate in apostolates and organized charitable activities, of course, according to their time and availability. But there are those remarkable families that are full-time missionaries serving in difficult places. Their are others who work with refugees or the poor.

Then there are people who develop Catholic media, publishing, music, and new forms of outreach for evangelization, catechesis, prayer and spiritual growth; and still others who dedicate their lives to the renewal of Catholic education on various levels, with a variety of methods, within long established academic venues or by founding new schools, universities, and programs. Eileen and I have done something like this, both of us being long-serving teachers dedicated to pioneering Catholic educational institutions, while also raising our own five kids. For us, the teaching vocation encompasses both the distinctive Christian apostolate of communicating the faith (teaching and writing about theological and religious subjects, and involvement in "Catechesis of the Good Shepherd") and the more general humanistic concerns associated with the overall renewal of pedagogy in our time - with classical depth, proven modern educational methods (university liberal arts and Montessori for children) and exploration of new formats for learning (a task which circumstances have forced upon us). It has been for us an enterprise involving the whole family, with our own children among the students and making their own distinctive contributions.

I'm not going to put our family out there as the stellar example of how to live this type of vocation, first of all because we're not finished raising all the kids. We're still working through it, facing new challenges and learning new lessons, praying and giving it our best, being humbled by our weaknesses and entrusting everything to Jesus, through Mary. Our kids are doing well so far (three of them are now adults), and - though we've had the perennial rough patches and awkward times and miscommunications - our family remains pretty close (thanks be to God). But we are still in the midst of "running the race." Secondly, of course, is the fact that our path has been particularly wacky and off-beat (mostly because of me), and therefore not the most regular example of how "the lay apostolate" is lived. (I can't propose myself as an example of anything. I am a wretched, incoherent mess of a human being - a sinner who, when he remembers, begs for and hopes wildly in the infinite mercy of God.)

Nevertheless, I know it can be done. I have seen inspiring examples of families who have done beautifully the tasks of this sort of life. Because I know the immensity of God's love, and because of these many other witnesses, I am willing to venture a few words about it.

The vocation to the "full-time apostolate" and family life will only develop rightly through a profound humility that pervades both parenthood and the work. This means being rooted in a personal relationship with Jesus that is sustained by prayer - but of course we need this no matter what we do, because life is realized in this way: by abandoning ourselves in trust and love to Jesus, and living as children of the Father in union with Him, led by the gift of His Spirit.

If a husband or wife, a mother or father (or both) devote themselves to an apostolate of evangelization, catechesis, or works of mercy, they do so because they have discerned that this is God's will. There are lots of different kinds of work (plumbing, engineering, information technology, construction, furniture sales, architecture, pig farming, scientific research, truck driving, etc) that are specified by their contribution to building up the temporal life of this world. These are all good and necessary kinds of work which can be (and God wants them to be) contexts for a vital Christian witness and love. Moreover work itself, offered in union with Christ and out of love for the Lord and our brothers and sisters, is "consecrated" as an effort that will ultimately bear fruit in the transfigured life of the Kingdom of God. The love of God is drawing all of the good in the course of human history toward a mysterious but real fulfillment in His glory.

So, let us remember, we can serve God wholeheartedly and do His will, witnessing to Christ and building up His Kingdom through love, in whatever circumstances He places us.

Some of us, however, are called to take up more explicitly some of the many tasks specifically involved in making Christ known and loved, by serving Him in various kinds of apostolic works and in caring for the poor and needy. These tasks are the form and content of the work of the clergy and those who collaborate directly with their ministry. But, as Vatican II emphasized so strongly, any baptized Christian can take up "the apostolate" as their particular work, form associations, and take their own initiatives - always, of couse, in communion with their bishop[s] and the bishop of Rome.

So what happens when married people with families (or people who eventually get married and have families) discern a particular calling to a "full-time ministry" or even a broader kind of work that is nevertheless defined by the explicit features of evangelizing, catechesis, pedagogical formation of the integrally Christian human person, or the particular facets of the spiritual or corporal works of mercy? It begs the question to say, "they should have become priests or religious if they wanted to do that stuff." The Lord is clearly calling and equipping lay people and married people to these tasks - often, indeed, people who are not looking for or expecting such a calling.

Indeed, in the context of today's radically secularized society, the lay apostolate can be crucial in extending the witness to Christ into realms not generally accessible to ecclesiastical ministry. It can bring the announcement of the Gospel out onto the roads of the world. Springing from the charisms given by the Holy Spirit to all the Church's members, lay apostolates can take shape with a freedom and flexibility that enable them to generate environments in which Jesus can be encountered on the margins of society, beyond the reach (and even beyond the knowledge) of the more "official" Church ministries.

But can you do these kinds of things and raise a family too? That is the challenge, the complexity of which cannot be denied. It remains possible inasmuch as God wills it and gives the grace to achieve it. The life requires ongoing discernment, and it may not be possible or appropriate for certain periods of time in a family's history. In many instances, the calling might only be temporary. At the right time, for a year or two, some mission could be taken up, after which it might be necessary to return to the stable, rooted lifestyle that is more naturally congenial to the human dimensions of family life in general, with more economic security and less demands on the work-life balance.

Apostolic work is work. It is hard work, which involves an intensive commitment, but usually brings a smaller material recompense than a "regular job" or career. On the other hand, the sense of purpose and creative personal participation inherent in apostolic work often motivate people to invest themselves very deeply in it for minimal financial compensation. It is important work! But the family also needs to eat, and they very much need the mother and father to be invested personally in the life of the home. These difficulties can be engaged in creative and fruitful ways, when the protagonists really allow Jesus the "space" to be at the center of all their endeavors. And it is true that "God provides" - sometimes in dramatic ways - what we need.

Insofar as we forget about Christ and stray off in the pursuit of our own ideas, however, we will have troubles. Our devotion to the apostolate can easily degenerate into emotional overinvolvement, controversies, partisanship, and infighting. We too easily drift into bad patterns of taking our spouse and children for granted, and neglecting our place in the family. We also cannot allow our generous and highly interested work-commitment to devolve into a timidness about making our basic financial needs known and making sure the institution takes their responsibility toward us seriously. Sometimes "God provides" by giving us the courage to insist on being paid what we need; in such circumstances an apostolate may discover that they have more resources than they realized.

Always pray and seek to do the will of God. This is all that matters.

A full-time apostolate requires making many sacrifices so as to prioritize family and service together, according to a proper order (because serving one another in the family takes precedence) but also with a loving openness to the demands this work can make on life, a capacity for a kind of "sacrificial flexibility," and a readiness to forgive one another again and again. It is necessary to discern and judge what serves the children and the family as a whole in their vocation to grow in love, and not simply what will maximize the "effectiveness" of the apostolate.

This means, emphatically, having different ambitions than the mainstream secular culture with its idolatry of external activism and material success. In this way of life, you must be doubly on guard against the vanities of celebrity for yourself or for your apostolate. You will have less of the big money but there will be other precious "riches" (in grace and in human things too). You also have to be willing to be a bit "idiosyncratic" (crazy?) for Christ. And above all you must pray pray pray pray and follow the Holy Spirit - because there is no "program" for how to do this.

This means, emphatically, having different ambitions than the mainstream secular culture with its idolatry of external activism and material success. In this way of life, you must be doubly on guard against the vanities of celebrity for yourself or for your apostolate. You will have less of the big money but there will be other precious "riches" (in grace and in human things too). You also have to be willing to be a bit "idiosyncratic" (crazy?) for Christ. And above all you must pray pray pray pray and follow the Holy Spirit - because there is no "program" for how to do this. There are tips, advice, and suggestions, yes, but every family has its unique qualities and needs, must respond to unique and ever changing circumstances, and receives the graces from God attuned to them as unique persons in that original, irreplaceable communion of love they constitute together.

It is necessary to walk with Jesus and rely on the gifts of the Holy Spirit, while also remaining obedient to the Church's shepherds and close to the sacraments.

Here there is so much that applies to every vocation to family life. Jesus in the Eucharist is central to every Christian life and vocation. Spouses, remember too that the sacrament of marriage in Christ has awesome power - we need much more confidence in what He can do through His enduring presence with us at the heart of this sacred bond. Then there is the sacramental grace of confession. We need this because we will fail fail fail again and again and again but we must never give up. God heals us according to His plan, which often doesn't "look" the way we expect it to, or unfold in the way we think it should.

Even in the most varied circumstances and places, we must live our vocation in community. Families need families, trusting in the Lord to weave together from our unity in Him the many threads that make over time the "organic," deeply human connections of friendship. And we must rely on our brothers and sisters in Christ to help support us, encourage us, and sustain us in prayer.

This is hardly and exhaustive reflection on any of these points. It's just a blog post. But let me end with one final observation: in an adventure such as this, we will discover in ourselves a great, generous sense of humor (and we will need it

November 17, 2020

"A Windy Day in Autumn" (Digital Art)

Here is my biggest, most laboriously crafted, and (perhaps?) most unusual work of digital art for the Fall season. I'm not entirely satisfied with it, but here it is.

Here is my biggest, most laboriously crafted, and (perhaps?) most unusual work of digital art for the Fall season. I'm not entirely satisfied with it, but here it is.We can call it something like "A Windy Day in Autumn."

November 16, 2020

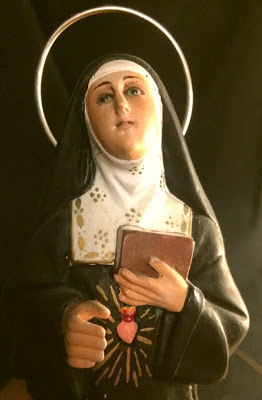

Saint Gertrude: Living in "Friendship With the Lord Jesus"

November 16 is the feast of Saint Gertrude "the Great," of the 13th century Benedictine monastery in Helfta (Germany).

November 16 is the feast of Saint Gertrude "the Great," of the 13th century Benedictine monastery in Helfta (Germany). She was one of the outstanding women of the medieval Church, a brilliant scholar, a counselor to many, and most importantly a mystic enraptured by the merciful and loving heart of Jesus.

In a vision, Jesus said to her, "My Divine Heart, understanding human inconstancy and frailty, desires with incredible ardor continually to be invited, either by your words, or at least by some other sign, to operate and accomplish in you what you are not able to accomplish yourself. And as its omnipotence enables it to act without trouble, and its impenetrable wisdom enables it to act in the most perfect manner, so also its joyous and loving charity makes it ardently desire to accomplish this end."

Reflecting on Jesus dwelling in her heart, she says, "Your sweetest humanity and unbounded love moved you to seek me in my disturbed state" and, hearing the words of the Scripture of John 14:23, "I perceived your presence in my heart, my most sweet God and my delight. It would be purified from its dross and made less unworthy of your presence.... My mind still takes pleasure in wandering and in distracting itself with perishable things. Even so, when I finally return into my heart after some hours, days, or even entire weeks, I still find you there. I cannot complain that you have left me even for a moment."

Gertrude is a wonderful witness to the merciful love of Jesus who accompanies us, who always takes the initiative to call us and move us toward a deeper relationship with him.

In his General Audience of October 6, 2010, Benedict XVI spoke of Saint Gertrude as "the only German woman to be called 'Great,' because of her cultural and evangelical stature: her life and her thought had a unique impact on Christian spirituality. She was an exceptional woman, endowed with special natural talents and extraordinary gifts of grace, the most profound humility and ardent zeal for her neighbour's salvation. She was in close communion with God both in contemplation and in her readiness to go to the help of those in need."

Although she "often says that she was negligent, she recognizes her shortcomings and humbly asks forgiveness for them. She also humbly asks for advice and prayers for her conversion. Some features of her temperament and faults were to accompany her to the end of her life, so as to amaze certain people who wondered why the Lord had favoured her with such a special love." Yet she lived with "such devotion and such trusting abandonment in God that she inspired in those who met her an awareness of being in the Lord's presence.

"In fact, God made her understand that he had called her to be an instrument of his grace. Gertrude herself felt unworthy of this immense divine treasure, and confesses that she had not safeguarded it or made enough of it... Yet, in recognizing her poverty and worthlessness she adhered to God's will, 'because,' she said, 'I have so little profited from your graces that I cannot resolve to believe that they were lavished upon me solely for my own use, since no one can thwart your eternal wisdom.'" In gratitude and charity, therefore, Gertrude dedicated herself to making God's love more widely known. She "devoted herself to writing and popularizing the truth of faith with clarity and simplicity, with grace and persuasion, serving the Church faithfully and lovingly so as to be helpful to and appreciated by theologians and devout people." And she wrote of her own experiences in prayer, in particular regarding the love of the Heart of Jesus: "'You wished to introduce me into the inestimable intimacy of your friendship by opening to me in various ways that most noble sacrarium of your Divine Being which is your Divine Heart.'"

Her mystical and prophetic gifts and her deep contemplative prayer were not experienced in isolation but always in the communion of the Church, rooted in the Benedictine tradition of liturgical worship and works of love. Therefore, Pope Benedict concludes, her story is "not only things of the past, of history; rather St Gertrude's life lives on as a lesson of Christian life, of an upright path, and shows us that the heart of a happy life, of a true life, is friendship with the Lord Jesus. And this friendship is learned in love for Sacred Scripture, in love for the Liturgy, in profound faith, in love for Mary, so as to be ever more truly acquainted with God himself and hence with true happiness, which is the goal of our life."

Prayer for the day:

in the heart of the Virgin Saint Gertrude,

graciously bring light, through her intercession,

to the darkness of our hearts,

that we may joyfully experience you present work at within us.

Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son,

who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, for ever and ever.

November 14, 2020

"Selfie, Autumn 2020"

Selfie, Autumn 2020. Just me and the leaves. Most of the first half of November has been unseasonably warm and very pretty in the Valley.

This is not something to be taken for granted. It is also not something that will last. Get ready for the COLD!

November 13, 2020

Hong Kong Opposition Leaders Resign in Protest

Democratic opposition members have resigned in protest from Hong Kong’s Legislative Council over Beijing’s new ruling that authorizes the region’s CCP-controlled “chief executive” to dismiss Council members without trial if they are deemed to be a danger to “national security.”

Democratic opposition members have resigned in protest from Hong Kong’s Legislative Council over Beijing’s new ruling that authorizes the region’s CCP-controlled “chief executive” to dismiss Council members without trial if they are deemed to be a danger to “national security.”

Once again the mainland has imposed its judgment and procedures without regard for Hong Kong's constitution, and in violation of China's international treaty obligations to respect the "One-Country-Two-Systems" agreement until at least 2047.

It has been a year since pro-Democracy candidates won a historic landslide in elections for the local-area administrative "District Council," which has no real political power. Nevertheless those elections were seen as a referendum on the Hong Kong protest movement's struggle against Beijing's encroachment.

Ever since, the CCP has continued to encroach more rapidly and openly. Dissent was outlawed by a mainland-imposed "national security law" in June, the Legislative Council election scheduled for this Fall was "postponed," and now four currently seated pro-Democracy LegCo members have been removed from office allegedly in the interests of national security. This prompted the remaining xx pro-Democracy LegCo members to resign in solidarity with their colleagues and to make clear that Beijing's abuse of power has removed every vestige of legitimacy from Hong Kong's constitutionally guaranteed legislature.

The air has been cleared of all effective pretense. This is a setback, of course, for now. It was inevitable, however, that those who favor Hong Kong's "self-determination" were going to have to play the long game. Protests have been effectively muted, but it remains to be seen how law enforcement and the judiciary will handle the many cases that have yet to be prosecuted against recent participants in the movement.

Now is the time for Hong Kong people to cultivate deeper growth and greater vision, whether they continue to live as they can within the region, or are forced into exile, or locked up in prison. Time is not exclusively the realm of those who use power to oppress the weak. Time can also strengthen the patience and widen the perspective of a concrete, non-violent, personalist and communitarian alternative for politics in Hong Kong (and elsewhere in the world of the 21st century that so desperately needs it).

Time allows the resources of the human spirit to come into play. In time, cries for justice, human dignity, and love will be heard.

November 12, 2020

Young Ronald Knox "Comes Home"

The young man who would one day be known as Monsignor Ronald Knox wrote his own account of his very moving conversion and entrance into the Roman Catholic Church at the age of 29.

The young man who would one day be known as Monsignor Ronald Knox wrote his own account of his very moving conversion and entrance into the Roman Catholic Church at the age of 29. I have written an article for my monthly published column, in which I attempt to present the broad outlines of a story that has many facets. You can read that article in the June 2021 issue of Magnificat (click HERE to subscribe).

On the blog, I wish to present a few segments from his beautifully written book, A Spiritual Aeneid (notwithstanding the fact that the more mature Monsignor Knox — who was a prolific author and translated the entire Bible — found this, his first Catholic book, inadequate and even embarrassing).

Nevertheless here he endeavors to explain the step he has just taken, with what is still the candor of youth and with the savor of the religious controversies (he had been an Oxford fellow, Anglican priest, and leader of the Anglo-Catholic movement) and the historical anguish of Europe in the midst of war in 1917. Knox's quoted text from A Spiritual Aeneid is in BOLD type. I interject a few contextual and/or explanatory notes in regular type which should appear as a medium shade of blue. Most of these notes are also contained within brackets.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------I suppose it is inevitable that, after the question “Why did you become a Roman Catholic?” Anglicans and others should proceed to the question “What does it feel like?”

In answer to this, I can register one impression at once, curiously inconsistent with my preconceived notions on the subject. I had been encouraged to suppose, and fully prepared to find, that the immediate result of submission to Rome would be the sense of having one’s liberty cramped and restricted in a number of ways, necessary no doubt to the welfare of the Church at large, but galling to the individual. The discouragement of criticism would make theology uninteresting, and even one’s devotions would become a feverish hunt after indulgences (this latter bogey is one sedulously presented to the would-be convert by Anglican controversialists).

As I say, I was quite prepared for all this: the curious thing is that my experience has been exactly the opposite. I have been overwhelmed with the feeling of liberty — the glorious liberty of the sons of God. I am speaking for myself, but I fancy not only for myself, when I say that as an Anglican I was for ever bothering about this and that detail of correctness — was this doctrine one that an Anglican could assert as of faith? Was this scruple of conscience one to be encouraged or to be fought? And, above all, was I right? Were we all doing God’s Will? or merely playing at it?

Now, this perpetual "is-my-hat-straight" sort of feeling is one that had become so inveterate with me as an Anglican that I had ceased to be fully conscious of it; just in the same way you can carry a weight so long that you cease to feel it; instead, you feel an outburst of positive relief when it is withdrawn...

[Knox felt as he had found his home in the Catholic Church.] I used once to define “home” as “a place where you can put your feet on the mantelpiece,” and I am not sure it is a bad description. That is the sense in which, especially, I felt that I had “come home.” Anglicanism (or some part of it) had, like a kind hostess, invited me to “make myself at home;” it was “Liberty Hall” [a literary reference to a place that welcomes people without imposing alien conventions]... and it was not till I became a Catholic that I became conscious of my former homelessness, my exile from the place that was my own.

It was not that, as an Anglican, I had been overscrupulous about other people’s disapproval: I always rather enjoyed being disapproved of. It was simply that I now found ease and naturalness, and stretched myself like a man who has been sitting in a cramped position.

“But,” I shall be asked, “what do you now make of Anglicanism, and of your Anglican career?”

It is not a particularly easy question to answer, but at least some misrepresentations may be worth the avoiding. I do think that I was called by God to minister to Him in the office of a priest; that I went about it the best way I knew, and was solemnly set apart as a religious person by a Body which had every human authority to do so, but lacked the spiritual qualification which is to me all-important, the direct inheritance of the Apostolic mission. The simplest way to put it is that, so far as orders go, I feel about the Church of England exactly what the Rev. R. J. Campbell (in his Spiritual Pilgrimage) says about his earlier ordination.

[Reginald John Campbell (1867-1956) was an ordained Protestant minister and notable preacher who then joined the Church of England. Campbell was "reordained" by what he believed to be valid sacramental bishops with apostolic succession in the Anglican Church (in reality, the succession had been broken in the 16th century, but he didn't know or acknowledge that fact). Campbell viewed his prior Protestant ministry as having a "charismatic" value for the leadership of the Congregationalist Christians he served, but not as possessing an objective sacramental status linked to the apostolic ministry instituted by Christ. Knox seems to be pointing to Campbell's description of his Protestant ministry as a "charismatic" gift of leadership and service ('grace-given' by the Holy Spirit, within the limits of the circumstances) for the sake of Christians entrusted to him who were honestly mistaken and in good faith in their dedication to following Christ. Ironically, Knox uses this distinction to illustrate the value of his own ministry as an Anglican priest, which he now realized was not truly linked to the apostolic succession. Nevertheless, it was "charismatic" and therefore a worthwhile service, and perhaps even — through the good-faith presumption of a validity that in fact did not exist — a ritual context that de facto provided occasions for "spiritual communion" (through intention and desire) with the Eucharistic Jesus who was really present, not at their Anglo-Catholic "Masses" but in the validly offered Masses by (validly ordained) Catholic priests all over the world. Knox himself was "reordained" (i.e. validly ordained) as a Catholic priest in 1918.]

As to the Sacraments I received, I feel as if I had in the past made a large number of spiritual Communions in circumstances where, for practical purposes, I was debarred from communicating sacramentally; that, consequently, if and in so far as I was in a position to receive grace at all, such grace was then given to me as is given in Spiritual Communion — I might have done the same if I had passed fourteen years of my life on a desert island. I have no sense of spiritual poverty — except such as we must all have.

As to the Sacraments I received, I feel as if I had in the past made a large number of spiritual Communions in circumstances where, for practical purposes, I was debarred from communicating sacramentally; that, consequently, if and in so far as I was in a position to receive grace at all, such grace was then given to me as is given in Spiritual Communion — I might have done the same if I had passed fourteen years of my life on a desert island. I have no sense of spiritual poverty — except such as we must all have. For the Church of England as an institution, my chief feeling is one of unbounded gratitude to God for having been born in circumstances where I had a schoolmaster to bring me to Christ. Or rather (for “schoolmaster” is too cold a term) I feel as if I had been left in charge of a foster-mother, who reared me as her own child.

Was it her fault if, in her affection for me, she let me think I was her own child, and hid from me my true birth and princely destiny? I have no word of complaint to make of any rough usage: rather, if anything, she gave me too much liberty, and let me put on airs when I had no right to. And if at last I have found my true parentage, as I now think it, can I forget the kindnesses she showered on me, her care and my happiness in her arms? Such is not my intention; God forgive me if through any fault of mine it should become my act.

“And so,” they go on, “you have found peace?”

Certainly I have found harbourage, the resting-place which God has allowed to His people on earth... despising the winds, not because no breath of air ever comes there, but because God himself has entrusted the command of those winds to his own Delegate, regemque dedit, qui foedere certo / Et premere, et laxas sciret dare jussus habenas.

I do not expect to escape temptations against the faith, such as the imperfect soul is bound to encounter and I have often encountered in the past. Nor do I feel cabined and cramped because intellectual speculation is now guided and limited for me by actual authority, as it has been hitherto by my own desire for orthodoxy. I find in the Church pacem veri nominis, quam mundus dare non potest, tranquillitatem scilicet ordinis; I do not see how it can be unchristian to desire that.

But if by “finding peace” you mean being laid up on a shelf and, like the housemaid of the epitaph, “doing nothing for ever and ever,” if you mean a sort of senile decay of the faculties, and a fatuous complacency in the existing order of things, then I no longer assent: then, like the irritated gentleman when a complete stranger asked him if he had found peace, I must answer “No! I’ve found War!”

Did I find, as the days of my hesitation drew to an end, the Church of Rome a smug, respectable institution much lauded by men of the world? Did I, in my morning paper, find fulsome paragraphs telling me of the debt we all owed to the Vatican for its admirable broad-mindedness?

Rather, if there was a wrong motive (for all political motives to religious action are wrong) which then encouraged me to join the Church, it was that I found the Church, as in the days of the Apostles, “a sect that is everywhere spoken against.” I found that Catholicism in Italy was condemned as denationalized, Catholicism in Germany for its nationalism, Catholicism in Switzerland because it was pacificist, Catholicism in France because it was chauvinist, Catholicism in Spain as a pillar of reaction, Catholicism in Ireland as a hotbed of revolution.

I found that the imperialist Press, both in England and in Germany, anathematized the Holy Father’s interference [i.e. Benedict XV's various efforts to mediate and help bring peace], now because he was trying to secure the winning side in its ill-gotten gains, now because he was trying to save the losing side from defeat. That [Rome's] influence should react differently in different environments was what I should have expected of the City which was built to be the world’s centre, but what did it all mean, this chorus of dissatisfaction?

In the first place, it must mean that the Church was something big, something significant — divine or diabolical, it must have some importance in the world, to evoke such antipathy. And in the second place, it had resolute and sworn enemies. The manifestations of its activity might differ, and the limits within which its influence could be traced might be narrower than many people thought, but still it had some effect, and the effect roused the world to fury.

Disagreements there might be between various sections of the Church — and its critics, heaven knows, have made the most of them — but at least it had one thing in common everywhere, common enemies..They might respect it for the moment, but in the years to come they would not be slow to join in assailing it, the indifferent, the baffled seekers after a sign, the fanatical opponents — as once before, Pilate and Herod and Caiaphas — sinking their differences in a joint attack upon this defenceless but never insignificant foe. Surely such a cause was worthy of being championed....

Disagreements there might be between various sections of the Church — and its critics, heaven knows, have made the most of them — but at least it had one thing in common everywhere, common enemies..They might respect it for the moment, but in the years to come they would not be slow to join in assailing it, the indifferent, the baffled seekers after a sign, the fanatical opponents — as once before, Pilate and Herod and Caiaphas — sinking their differences in a joint attack upon this defenceless but never insignificant foe. Surely such a cause was worthy of being championed.... Now, as I say, if such motives swayed me, they were wrong. It is cowardly to join the Church just because the Church is large, or influential: I had often had the argument put to me, and rejected it. They are slaves, who dare not be "in the right" with two or three. And it is wrong to join the Church because the Church seems to you to lack support which you can give. You must come, not as a partisan or as a champion, but as a suppliant for the needs in your own life which only the Church can supply — the ordinary, daily needs, litus innocuum, ei cunctis auramque undamque patentem.

You must join the Church as a religion, not as a party or as a clan.

[This was the religion — the fullness of the way of surrendering his will to Christ — that Knox encountered with an open heart, after much struggle and inner turmoil in the stretch of time immediately prior to the completion of his conversion: for him it was the decisive step on a road that passed from his Evangelical childhood, to his Ritualist Anglican school days, to his zealous convictions as an Anglo-Catholic priest who wanted to help liberate and bring about the (future) "corporate reunion" of the whole English Church with Rome, to — at last — his personal entrance into the fullness of faith and communion with the Catholic Church in obedience to Christ, and the successor of Peter. In the end, after all his seeking, he went on retreat to a Benedictine monastery and prayed to be able to make his decision. Soon] I knew that grace had triumphed. I neither expected nor received any sensible supernatural illumination: I did not have to take my spiritual temperature, “evaluate” my “experiences,” or proceed in any such quasi-scientific manner. I turned away from the emotional as far as possible, and devoted myself singly to the resignation of my will to God’s Will. Attulit et nobis aliquando optantibus aetas Adventum auxiliumque Dei; in the mere practice of religion, in the mere performance of these (very informal) exercises, I knew that it was all right.

I am not trying to explain it, but I must try to illustrate it by an example. It was as if I had been a man homeless and needing shelter, who first of all had taken refuge under a shed at the back of an empty house. Then he had found an outhouse unlocked, and felt more cheerfulness and comfort there. Then he had tried a door in the building itself, and, by some art, found a secret spring which let you in at the back door; nightly thenceforward he had visited this back part of the house, more roomy than anything he had yet experienced, and giving, through a little crack, a view into the wide spaces of the house itself beyond. Then, one night, he had tried the spring, and the door had refused to open. The button could still be pushed, but it was followed by no sound of groaning hinges. Baffled, and unable now to content himself with shed or outhouse, he had wandered round and round the house, looking enviously at its frowning fastnesses. And then he tried the front door, and found that it had been open all the time.

November 10, 2020

Christina Grimmie is "Never Giving Up"

It's November 10th. I was listening to this song by Christina Grimmie today. Steady Love.

In whatever mysterious way, I hear these words directed to me personally. They are a witness. They are helping to build something within my soul, something I can't make by myself.

I'm counting on that "steady love," that love stronger than hatred and evil. Stronger than death.

Christina's songs are full of "promises" like these. After four years and five months, I still find her convincing.

November 9, 2020

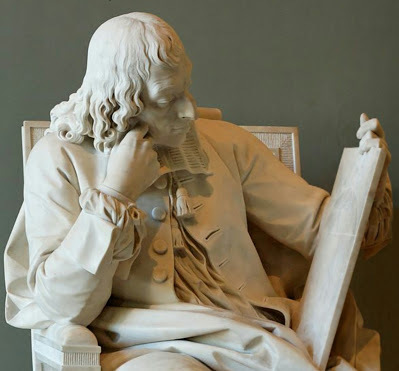

Reality and the "Thinker"

The thinker is reflective. He tries to understand the world and himself. He looks at the way things are, how they are structured, how they are distinct and how they go together. He tries to understand himself. He reflects on his own experience and he tries also to understand and appreciate from within the experience of others.

The thinker is often not the same as "the debater"...the thinker can get frustrated with arguing, especially in the combative contemporary forum in which it takes place. It is not that he lacks appreciation for disagreement, or for challenges to his own ideas. It is rather the opposite: he values them too much. If he encounters a coherent challenge to his understanding, he wants time to examine it and if necessary alter his own thinking. In the face of a bad argument, he is often more interested in what the "opponent" is really trying to get at, or what genuine insight might lie behind a poorly formulated position.

This means that the most gifted and articulate thinkers can sometimes be the best debaters. They are able to distinguish and clarify. They are not so much interested in "winning an argument" as they are in joining with their interlocutor in a search for the truth. They don't "beat" their opponent; they "win him over"--and in the process often find their own positions clarified.

Such persons are rare, however. Most thinkers are like Rodin's fellow up there. They are plodders. They are often insecure in their own ideas, and find that grappling with intellectual challenges is a painful psychological process of struggling with doubt, with feelings of weakness and incompetence, and with frustration at the sheer murkiness and dimness of the human intellect. Step by step, with many mistakes, and only with a great deal of time does the thinker begin to grasp truths that are really worth knowing.

The thinker is often a peacemaker rather than a warrior. But he has his own kind of courage: he is courageous in his willingness to suffer the long human journey to truth. There is a secret fire that sustains him.

The thinker, however, considers things in the shadow of a great temptation. It is a subtle, but devastating temptation. The thinker wants to understand everything. He craves intellectual synthesis.

He can even have it, up to a point....

He can know something about the Mystery that is the source of all reality if he is willing to yield his mind to the way of similitude and difference, the way of analogy, where knowledge humbly gives way before a certain darkness, where he adheres to and affirms a transcendent "Other" whose secrets are too great for him. What he sees is only in a mirror, and what he does not see is always the greater.

To be humble before the ultimate truth of reality is his greatest challenge. It is difficult, because the thinker has a quiet, often unacknowledged, but fiercely stubborn pride.

Perhaps this is why Rodin's fellow is looking down.

The hardest thing for the thinker is to look at reality, at the actual life that greets him every day. The real things in life are given their deepest meaning by an absolutely gratuitious Love that has freely chosen to take up and give itself from within the whole business.

Shocked by this Love, the thinker is tempted to withdraw into himself. He struggles with all his mental energy to incorporate this Love into his synthetic project. There must be categories in which this can be contained.

St. Paul spoke to the thinkers of Athens. He intrigued them with his appeal to the "Unknown," but then a strange thing happened. He pointed to an event, to gratuitous Love, to a man who has risen from the dead. Some of the philosophers just laughed at him, but I have always wondered about those who said to him, "we will hear you on this another day" (see Acts 17:32).

How typical of the thinker.

In front of the explosion of Love, he says, "can we talk about this some more? Perhaps you can explain yourself?"

But Love does not explain itself. It says, "follow Me."

There is a story about Thomas Aquinas. It is about something that happened one day while he was deep in

thought in his room at the Dominican friary in Paris - while he was pondering the highest questions and working on his manuscripts (which of course have so much value for the history of philosophy and theology). The Prior of the house told a young novice to find a friar who wasn't busy and tell him that the Prior needed him to go to the center of town and buy fish for the community.

Aquinas was the first friar that the ignorant novice saw. The great scholar, the Magister of the University of Paris, one of the great geniuses of all time, was approached by a novice, who told him that the Prior had ordered him to go out and buy fish.

Without a moment's hesitation or question, Thomas put down his pen and headed for the fish market.

November 6, 2020

"Our Citizenship is in Heaven"

November 5, 2020

Pascal: "What It Is To Be A King..."

He's paradoxical. He's provocative. Sometimes, he's a bit extreme. But Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) makes you think... and I'm not talking about mathematics or science here. I'm talking about the collection of his "Thoughts" published after his death at the age of 38.

He's paradoxical. He's provocative. Sometimes, he's a bit extreme. But Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) makes you think... and I'm not talking about mathematics or science here. I'm talking about the collection of his "Thoughts" published after his death at the age of 38. The Pensées were more like notes or fragments of a book when he died, but they were published and read widely, and continue to be admired for their brilliant French prose, and their profound religiosity.

In fact, reading them is like having buckets of existential cold water dumped on your head. When the world grows fuzzy, when everything is distracted and out of focus, Pascal can be very good reading. He speaks about the human condition with great insight, and also with hyperbole that can go too far and paradoxical articulations about human interior dividedness that draw much from his passionate Jansenism. Yet even when he stretches things thus, he always has a point. You can't simply dismiss his challenge to face the evasiveness and duplicity of your own life, and the cheap distractedness of the dominant mentality and so many cultural trends.

Pascal refuses to allow you to be comfortable with any self-sufficient worldliness, with the forgetfulness of the human need for God. With poetic eloquence, he draws a picture of the human condition according to the volcanic incoherence of human behavior, of "the grandeur and misery of man." Thus, he is existentially provoking. And he speaks to human problems today as much as those of his time.

"Man is obviously made to think. It is his whole dignity and his whole merit; and his whole duty is to think as he ought. Now, the order of thought is to begin with self, and with its Author and its end. But of what does the world think? Never of this, but of dancing, playing the lute, singing, making verses, running at the ring, etc., fighting, making oneself king, without thinking what it is to be a king, or to be a man" (Pensées 146).

Topical, indeed. We are all still taken up with the question of "who is to become king," without thinking much about what it really means to "be king," and putting it in perspective: the person who wears the crown will be neither our savior nor our ruin. We are made for God. He is in control. Our identity comes from Jesus, the King of kings, and not from our tribes or our chiefs. We follow Jesus. We trust in Him, come what may.

Pascal's text is also a finger pointing at me, certainly. I want to say that I can think of my self, God, and my end, while also giving attention - critically, of course - to the relative values of playing the "lute" (especially the "electric lute") and singing and writing verse and playing ball. I tell myself that I'm trying to recognize the human values that are all wound up with the ambivalence and excess of these activities in today's society. That's what I want to do, but I'm also lured sometimes by the distractions, the cleverness, the spectacle. Being a Christian "in the world" is a vocational duty, but I am far from doing it well. I need more prayer, more attention to the word of God, more asceticism, more remembrance of Christ, more openness to the grace of the sacraments, more awareness of belonging to God, more desire to do His will.

Pascal is a "reality check" on all pretenses to compromise, to settle for mediocre Christianity instead of striving for a greater conformity to Jesus Christ.

In another text, the great French prodigy of math and science, the genius of invention, the passionate religious penitent lays before us all the paradox and ultimate helplessness of human reason's effort to establish the measure and value of human existence. The rhetoric exhorts us to look beyond ourselves, to listen to Another...

"What a chimera, then, is man! What a novelty! What a monster, what a chaos, what a contradiction, what a prodigy! Judge of all things, imbecile worm of the earth; depositary of truth, a sink of uncertainty and error; the pride and refuse of the universe!

"Who will unravel this tangle? Nature confutes the sceptics, and reason confutes the rationalists. What, then, will you become, O men! who try to find out by your natural reason what is your true condition? You cannot avoid one of these positions, nor adhere to one of them.

"Know then, proud man, what a paradox you are to yourself. Humble yourself, weak reason; be silent, foolish nature; learn that man infinitely transcends man, and learn from your Master your true condition, of which you are ignorant. Hear God" (Pensées 434).