Nicola Griffith's Blog, page 76

March 25, 2015

Leigh Brackett’s The Long Tomorrow

This is an essay that was published in 2012 by the Library of America as part of their American Science Fiction: Classic Novels of the 1950s series (edited by Gary Wolfe). The other links on that page—an audio interview with Brackett, essays on other writers by people like Tim Powers, Michael Dirda, and Connie Willis, and more—are well worth following.

I read The Long Tomorrow for the first time in 2005. Five pages in, I wondered why I’d never heard of this novel. Twenty pages later, I was wondering why it wasn’t universally acknowledged as the first Great American SF Novel.

The opening of The Long Tomorrow reads like a King James Bible for the American myth: rhythmic, certain, implacable. It says: This is how it was. It leaves no room for dissent. Brackett sets up her major theme in the first sentence: “Len Colter sat in the shade under the wall of the horse barn, eating pone and sweet butter and contemplating a sin.” The sin is knowledge, and with that one sentence we’re right there with fourteen year-old Len, seeing for the first time the limit of his experience, standing on the edge, about to take the step that will lead to his loss of Eden.

Brackett’s themes are those of the Bildungsroman: loss of innocence, change, and the journey from safety into the unknown in pursuit of knowledge. But because her ambition was enormous, her setting is that of a post-nuclear Ruined Earth. She aimed for no less than the first serious novel of character set in an sfnal landscape.

In mid-century North America, I doubt there was anyone better equipped for the challenge.

Before Brackett wrote The Long Tomorrow (published in 1955), she was expert in two disparate traditions: swashbuckling planetary romance (for the sf pulps) and hard-boiled crime narrative (a novel, and several screenplays, e.g. The Big Sleep). In 1949 she tried to mix aspects of these previously immiscible traditions. She added the grit, realism, and noirish interiority of hard-boiled fiction to the exoticism of an elegiac Mars dreaming of long-forgotten technology.

The result was The Sword of Rhiannon, a smooth planetary romance startlingly cabled with gristle. But Rhiannon fails as literature: the hero doesn’t grow and change. So Brackett tried again, and this time she chose a landscape that Huck Finn might have recognised. (Though peopled, it must be noted, entirely by white characters—with one exception.)

She flung herself into territory both old and strange. Into a base composed of tropes familiar to any reader of the Great American Novel—the young hero seeking his place in the world, a farmland America of rich dirt and strong faith—she poured a healthy dose of sfnal anti-anti-intellectualism, and, perhaps inevitably, the refusal of the hero’s expected return—older, wiser, and reconciled to his place in society—to his beginnings.

The first third of the novel is undeniably brilliant. Len Colter is part of his world, steeped in it, thinking in the same rhythm with the same vocabulary as his community. By the simple expedient of constitutional prohibition against cities and deeply faithful leadership, Brackett shows the reader the clear connection between religion and the maintenance of cultural taboo. We see how technology has become taboo. We are introduced to the notion of a possibly mythical pariah elite of Bartorstown—who, naturally, are technologists. We watch the inevitable fall from grace of Len and his friend Esau, and the beginning of the long, long journey to self-understanding.

Brackett, like Len, is a product of her age. While the religion is beautifully handled—it is shown in a variety of sects, and held with varying depth of feeling—it is entirely Christian, white, and run by and for men. She shows men, though not women, struggling to be good people inside their constraints.

She also handles the antagonism of science and religion honestly. She melds the classic noir cri de coeur, Why me?, with Len’s sfnal anti-anti-intellectual crisis: “Oh God, you make the ones like Brother James who never question, and you make the ones like Esau who never believe, and why do you have to make the in-between ones like me?” In an even more impressive feat, she uses what would be a literary novel’s denouement, Len’s realisation that faith is just another word for fear, to disguise a classic sfnal move: a vertiginous focus pull in which he understands that he is nothing, a speck, immaterial to continuing existence of the world.

It’s fascinating to watch Brackett lay out her chainsaws and clubs and flaming torches and add them, one by one, to the performance. Every now and again she falters—in the third section, when she has the most in the air, her voice veers into an unconvincing present-tense stream-of-consciousness, her characters lose focus, and this reader at least doubts the viability of Bartorstown’s sfnal mission—but then she drives a brilliant spike through the confusion and pins us to the here and now. I defy you to get through the moment of Joan walking through that doorway in her red dress and not be right there inside Len’s skin, feeling him swallow and his world turn, just as it did on page one.

In the 1950s, this book must have turned its readers inside out like a sock. It wouldn’t surprise me to discover that this novel was a formative influence on the young Carl Sagan, the genesis of his notion that spacefaring nations would be rare because they would tend towards destruction before they escaped the gravity of their planet.

In the twenty-first century, we have an inkling that this may not be true. Perhaps we have writers like Leigh Brackett to thank.

March 20, 2015

Two blog posts on Gemæcce

I forgot to mention, I just did two posts over on Gemæcce, my research blog. Both full of pretty maps. The first is about the battle of Hatfield Chase. The second a few thoughts—questions, really—about the recent Nature piece in the genetic structure of the population of Britain.

Quick follow-up

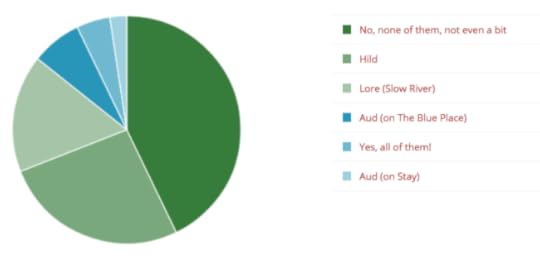

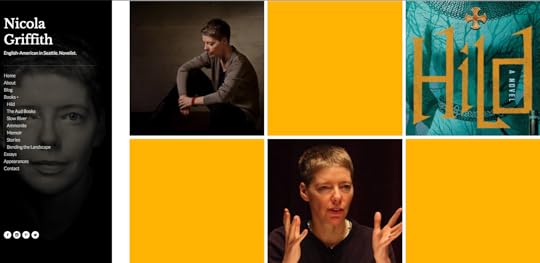

So, I asked you if I looked like my protagonists. The results are in.

So: I win! That is, those answering “No, none of them, not even a bit,” are 42.6% of the total, as much as the next two largest sets combined…

…Which just goes to show how you can make statistics say anything, because if you look at it another way, more of you think I do look like at least one of my protagonists (57.14%) than those who don’t (42.86%). So: I lose!

But it was fun. Thanks for playing.

March 16, 2015

Protagonists who look like their authors

I’ve lost count of the number of readers who have suggested I look like one of the protagonists of my books, as illustrated on their covers. The first time it happened was with Slow River. I was surprised, but then came The Blue Place*, and Stay, and I became progressively less surprised. With Hild I expected it.

But I think you’re all on crack: I don’t think I look like any of my protagonists. Lore, for example, is glossy as a racehorse with perfect teeth. Aud is six feet tall with eyes the colour of cement (though I admit we did both have white-blonde hair for a while). Hild has chestnut hair—and is even taller. I don’t see it. But by now I’ve become so used to the confusion that when readers comment on it I smile blandly, say, “I get that a lot,” and move on.

However, at a recent literary festival—the first time for a while I’ve done public Hild stuff—several people mentioned it. And a couple of days ago a reader, Cheryll, asked me if the fact that the painting of Hild looked “exactly like my author photo” was intentional or “just a remarkable coincidence.”

So I’ve decided to approach the question again with an open mind.

First, though, let me be quite clear about one thing: it was not my intent that the Balbussos’ painting of Hild look like me. I didn’t want Hild on the cover at all. I can’t speak to the artists’ intent but I suspect it wasn’t theirs, either. For one thing, if they even saw the author photo, which was shot by Jennifer Durham in January 2013, they must have worked blindingly fast: the cover was ready at the end of February.

Cheryll said:

Look at the eyebrows. Look at the front of the nose and the way the light catches it. Most of all, check out the coolly appraising yet open and curious gaze. Maybe you can’t see the resemblance because you’re comparing what you see in the mirror with the image on the book cover. I and the others who’ve noticed this resemblance are comparing the cover with a photograph. So I think that’s what inspired the Balbussos. Certainly they’d read the book. So perhaps it’s not so much that you look like your protagonist; it’s that they’ve made your protagonist look like (the image of) you.

Yes, in the painting Hild’s eyes and hair colour are as described in the book. But they’re not like mine. I don’t think. It’s actually hard to say what colour my eyes are, exactly; blue, yes, but they tend towards green when I wear green, and grey when I wear grey. (Compare the colours in my two author photos.) My hair colour is quite different. My stylist describes it as “dark blonde” (stylist-speak for “light brown”) and when I was younger it was blonde. Now it’s flecked with grey, and after a few hours in the sun bits can turn gilt-bronze. But chestnut (red-brown)? No.

However, it’s clear that some readers see a resemblance even if I don’t. So I asked Cheryll if that perceived resemblance helped or hindered her connection with Hild while she read. She told me neither—that she hadn’t noticed it until she was halfway through the book and had already formed her opinion.

I was glad about that. I can get irritable when readers of any stripe think my protagonist is just a Mary Sue. I’ve talked about this a bit before, for example in an interview a few years ago for Always:

What’s your relationship to Aud? How does her personality relate to your own? Is she the character in these books who’s most similar to you?

Who is the Mary Sue character? Aud, with her martial arts, foreignness, and self-defence? Yes. Kick, with her size and shape, her MS, her love of food? Yes. Dornan, with his optimistic entrepreneurship, hypothetical questions and love of philosophy? Yes. Else, with her need to change the world and adherence to simple design principle? Yes. Eric, with his cheerful love of wine and fast cars and pop culture? Yes. Corning with her hope she can get away with bending the rules and getting what she wants? Yes. Rusen, with his need to make something good even though he doesn’t really know everything he needs to? Yes.

They’re all me. The more minor the character, the more minor the facet of my own character I’ve chosen and sharpened and polished. I love them all, even the not-so-nice ones.

Aud is a path-not-taken character. I’m not American. I do understand self-defence. I do care about justice. I am practical. I have studie martial arts. I can imagine a universe where I might have ended up a bit like her if I hadn’t fallen in love when I was fifteen, if I were six feet tall and rich and Norwegian and physically able. Kick has MS and small hands; so do I. But she’s American and an ex-stunt actor. And she didn’t run a mile when she met Aud. I think I would have done.

All my fictional characters, major and minor, are infused with me and my experience to some degree. Like the people in our dreams, they have to be: imagination begins in experience. My hope, though, is that they take on their own personality.

To settle the question once and for all (also to continue my quest to learn all of WordPress’s nifty tools) I’ve created a poll. I want you to give your opinion (you will be anonymous to me, so don’t be shy); I’m braced for any result.

Take Our Poll

* A twist on this with The Blue Place: I also had a zillion readers (well, scores anyway) ask if I had the phone number/email address/name of the woman on the cover. For years I had no idea…and then I did.

March 14, 2015

Doing the Work

Written just before the publication of Stay, the second Aud Torvingen novel, this essay was first published in BoldType in March 2002.

Even though I can list in my sleep the questions I’ll get when Stay comes out, I’ll still be struck dumb when they’re asked because the answers are all connected and about as easy to explain as why being alive is a good thing. People will ask, Where do your ideas come from? Why do you write what you write? Why do you write about the kind of people you write about? Why did you choose to work in the noir genre? Why make your main character a woman? but what they’ll really want to know—and will be too polite to ask—is, Don’t you think Aud, her personality and attitude to violence, is a bit, you know, unrealistic and over the top? As far as I’m concerned, life’s too short to sidestep around anything so I’ll just cut to the chase, and begin with this matter of Aud.

Aud is my commitment to excellence made flesh/word and walking around; she uses whatever it takes to get the job done. She is the tension between the joy and discipline that is my art (or craft or life or bane, depending) filed to a point and stabbed into the tabletop. She is a public challenge—to me and from me—because there’s no way to disguise the meaning of a naked blade quivering in the wood: the game is serious, the personal stakes high.

Before I wrote, I sang, and before that I played various sports, studied martial arts and other things, but no one ever asked me why I sang (or loved using my body) because the answer is self-evident: it feels good. Singing is a visceral act: vocal cords thrum in the throat and set up a resonating hum in the diaphragm, muscles squeeze and air flows from lungs to throat to mouth to atmosphere. Get it right and you can feel the vibration in your bones—a sort of internal massage. Lovely. When I studied martial arts it was the sheer physical thrill—adrenalin, sweat, speed, balance—that made me want to throw back my head and laugh. Writing is no different. Sometimes I wake up in the morning and I fizz and itch with my eagerness to write. I get to that keyboard and zzzsst, it’s like sliding down a greased ramp into white water. There’s nothing but light and liquid and weightlessness. If something hurts I no longer feel it; my music playlist ends but I don’t notice. I’m riding the turbulence, bringing to bear every mind muscle I possess, flexing, leaping, diving, cleaving the water like an Olympic swimmer. It’s a rush, an absolute joy.

Joy can take a swimmer, or singer or writer or karateka, a long way but at some point, if you’re serious, you have to accept the discipline of work—which is of a different order than mere effort. An Olympic swimmer doesn’t win gold by just swimming a long way every morning. She spends a mind-numbing number of hours setting her toes just-so on the starting block, bending, diving, taking two strokes, pulling herself out of the pool and back onto the block, bending at a very slightly different angle, and diving again. And again. Over and over. And if the angle thing doesn’t work, she’ll swear, and shrug, and start messing with the toe placement, then the arm angle, and the hand shape, all in the quest to shave another two hundredths of a second from her time. This kind of work is unglamourous, frustrating, repetitive and occasionally heartbreaking. It requires a discipline and commitment that, until I accepted that I’m a novelist, I’d never needed.

My first novel was published in 1993 but I didn’t really understand what it meant to be a writer until the summer of 1998. My third novel, The Blue Place, was a couple of months from publication and I had no idea what I wanted to write next. Or should I say I had many ideas but I couldn’t settle to anything. I’d prepared a collection of short stories and essays, started research for a historical novel, started editing an original anthology series. I bought a couple of books about screenwriting. I began to study aikido. I considered learning to draw or to speak Spanish. And every now and again I’d think about Aud. There was a great deal still to write about her, if I chose, but the idea sent me into a kind of panic. One summer evening I was sitting on the porch in the sun, drinking beer, nodding at passersby in the neighbourhood, mind on nothing in particular, when I found myself imagining not writing anymore. I was picturing going back to school to study ancient history, or going back to teaching self defense, even going back to England. I remember one minute wondering idly how much we could put the house on the market for, and the next blinking at my beer, thinking: Put the house on the market? Move? Why? Well, because we’d bought it three years ago and I’d never lived anywhere longer than three years, so it was time to move. QED. After all, if I stayed, I’d have to make some choices like…like, oh, what color to paint the walls, and what sort of furniture to put in my office, and what to plant in the garden. I’d have to stop living in the house we’d bought and start living in the home we’d made. That would mean making some choices. The house would lose the potential to be perfect because I would have to start dealing with specific, real, practical limitations. I realised that what I was contemplating was running away: from writing, from doing the work.

I don’t like work. I’ve spent most of my life avoiding it, picking up singing or karate or a course of academic study, finding it easy, and then walking away the minute friends or teachers or fellow students began expecting things and dropping unsubtle hints about practice schedules and rehearsal times and future intentions. Now, staring at my empty beer bottle on the porch, I began to understand. It wasn’t the effort I was afraid of but what making that effort meant. I always walked away when I reached the stage where I would graduate from being a beginner to a serious student. This is the point where the speed with which I learned something would mean less than how deeply I learned it, and what I might do with it, where I might take it on my own. To progress meant having to do the work. It meant that if I failed it wouldn’t be because I hadn’t bothered to try but because I had limitations. I can’t tell you how much I hated that realisation.

I got another beer and thought about Aud. There was a lot more to discover about her, and I was afraid I wasn’t good enough to get it right. I’m still afraid.

I don’t like the idea of failure, of discovering limitations, or of work, but when I write I face all three every day. I keep doing it because it feels good and because, for the first time, the work—product and process—is worth it.

One of the things I wanted to write about in Stay is grief. My little sister, Helena, died in 1988. When I began the novel in 1998 I intended to use Aud and her grief to talk about me and mine. I wanted to write out, finally, all the things I’d learned in ten years of mourning. I finished the first draft at the end of 1999. It was not good. My grief—for a sister to whom I’d been a surrogate mother, whom I’d known every single day of my conscious life and lived with for a great proportion of it—was not and could not be remotely like that of a Norwegian woman of twisted emotional development who had lost a lover she’d known only six weeks. Except that I knew deep down that grief is one of those universal human emotions, like fear or love or anger, whose essence is the same no matter what the individual circumstances. So what I had to try figure out is what about my grief was particular to me, and what was universal. To do that I had to revisit my sister’s death in detail. Then I had to take what I understood of that essence and shine it through Aud to see how the lens of her particularity would diffract its colour and shape. I began the first rewrite. A year later, as I began my seventh rewrite, I discovered that another sister, Carolyn, had only six months to live. I was on my tenth rewrite when she died. I was on my twelfth when the Twin Towers collapsed.

I rewrote Stay thirteen times. It got harder each time. I was tempted on two separate occasions to stick the manuscript in a drawer and forget Aud, go back to that historical novel I’d been toying with. It felt awful, working on that book, as though I was tearing open a wound over and over, as though I was damaging myself. It’s possible that I was, of course, but it’s just as likely that the pain was simply the equivalent of stretching a tendon shortened by disuse. It hurts, but it’s not harmful; it’s just work. Work, frankly, sucks. Like failure it’s no fun. Unlike failure, though, it feels good afterwards.

The annoying part of all this is that one of the ways I know I’ve done a good job is that no one sees how hard I’ve worked. When a television audience is watching that Olympic swimmer, they don’t want to know about the tens of thousands of hours he spent perfecting his start or the physical therapy he’s had to have on his shoulder or the deprivations of diet and social life. When those viewers turn off their televisions and go to the theatre to watch Hamlet they don’t want to see Laertes screwing up his face in an effort to get the meter right; they don’t want to know how difficult it is to make that iambic pentameter sound like natural speech, or the fact that Ophelia has a sprained ankle from throwing herself too enthusiastically at Hamlet’s feet during dress rehearsal. The theatergoer or reader might not object to doing a little work, in fact most of the time I think they like it, but they don’t want to have to watch it. What the reader wants—what I want as a reader, anyway—is a seamless experience. I don’t mind admiring the work afterwards but when I’m in the middle of a novel I don’t want to be thinking, Wow, you can really see how much effort she’s put into this research, or He must have spent a days figuring out that tricky time-shift sequence. When I’m in the middle of reading I want to be thinking (and feeling) Oh, god, I wonder what I’d do if it were my child dying, or Huh, I never thought of responsibility in quite that light before, what an interesting way to look at it. The first time I read a novel I want the author’s technique to move like a vast iceberg beneath my consciousness: unseen, felt only in passing.

Nine times out of ten, if you see how hard the writer is working it means he hasn’t worked hard enough. I believe that if technical mastery is a feather then it should be on the writer’s arrow, not in her cap. Admiration for flashy and obvious writerly technique on the part of critics who should know better is one of my (many) pet peeves. Having said that, I admit that as a reader I love to catch just one fleeting glimpse of exuberance from the author, a just-for-the-hell-of-it paradiddle because I believe feeling good is integral to art, both to the creator and consumer. It’s important for me to be able to sense on some level that the writer had a great time doing her job, that it mattered: she burned to describe this interface between the character’s interior and exterior worlds and how each impacts the other, or he was just so enthusiastic about plainchant that he couldn’t wait to impart his love and knowledge of the subject to his reader, or whatever. Whether the book ends happily is immaterial, but somewhere, even in the grimmest novel, there must be a gleam of rough joy. A whole novel without it is unbearable (and pointless).

Joy is one of the reasons I don’t see Stay as a noir novel. Noir, the way I understand it, is all about being trapped by circumstance. It is about ordinary people leading small lives who make one mistake and, phht, that’s it, it’s all over, because when they try to correct their mistake they just end up digging themselves a deeper hole. At every moment of the novel they and the reader know that their eventual downfall is inevitable. They struggle against this inevitable end not out of a need to hold onto something good in their lives, but because they are so mired in their own circumstance they don’t know what else to do. On those occasions where they appear to avoid punishment for their deeds (Highsmith’s Ripley, Hammett’s Spade), they and we know that it doesn’t matter: their own essential nature dooms them to repeat their mistakes. Noir is the horror fiction of the crime genre.

The joy of a good novel can be as varied as the joy of dance: the stately precision of a pavane, the raw vitality of flamenco, the familiar pleasure of an old married couple fox-trotting on their anniversary. When we dance, what we feel is not ordinary and everyday; we feel bigger, brighter, more vital. In much the same way, a fictional character does not have to be ordinary to be psychologically real. Sappho and Stalin, Janis Joplin and Jesse Owens, the Marquis de Sade and Mother Teresa all lived extraordinary lives; all were real. Aud is not ordinary, either—Aud and ordinary don’t even live on the same planet—but she’s as real, as true emotionally and psychologically as I can make her. She is herself.

Aud is not my puppet but she is my living message, my envoy (it’s just a shame she’s not much of a diplomat). She embodies the long journey towards reconciliation of all those parts of our culture that have been artificially levered apart: mind and body, nature and civilization, art and science, man and woman, tenderness and brutality. She reflects the endless building and dismantling of human understanding: learning, and unlearning, then relearning differently. She is the work. Like art, she is a contradiction and a bridge: between me and you, past and present, moral and amoral, change and stability. She’s a tender, violent woman who has never been a victim; she understands but remains unmarked by cruelty or gender. She can both do and be, viscerally and intellectually. She is mercurial and implacable; she deceives herself then sees clearly. Like life, she is fragile and impossibly resilient. She is willfully individual and in so being becomes my knife in the table, my reminder that the public challenge has been made and there’s no way to back down and walk away. I’ve committed us both. She and I will make mistakes and get knocked down, and when that happens we’ll get up, give the world a bloody, half-crazed grin and set to work again with an even tighter focus. We’ll do the work because it’s worth it. It will even feel good.

March 11, 2015

Girls of lost subcultures

After my last post, a nostalgia piece for International Women’s Day and Janes Plane, I found out* that I’m apparently one of the “girls from lost subcultures” in a photography exhibit, Visible Girls, by Anita Corbin.

In the summer spring of 1981, when I was 20, I went down to London with my partner, Carol (we lived together for ten years before I moved to the US to be with Kelley), for the first UK Lesbian Conference. It was academic and political. Carol and I were there, though, to party. And at the social we got seriously wasted on magic mushrooms. If I recall correctly (and that’s a big if—in those days I took a lot) Carol began to freak out a bit—those of you who are familiar with the psilocybin cycle know that this can happen to some people; it generally doesn’t last long—and I led her to a dark wall and put my arm around her to shelter her from the worst of the noise and light until she found her equilibrium. Just as she was breathing and calming down (but was not quite out of the woods) a woman with a camera appeared and asked if she could take our picture. I was a bit fretful behind my euphoria—mushrooms are like that—worried about Carol, feeling super-protective, and was about to say no when Carol beamed and said, “Yeah, let’s do it!”

At which point the photographer, Anita, took this picture.

Photo “Nicola and Carol, The Tabernacle, Notting Hill Gate, April 1981″ by Anita Corbin

Photo “Nicola and Carol, The Tabernacle, Notting Hill Gate, April 1981″ by Anita Corbin

Then I thought no more about it and got on with the serious business of reducing my mind to a microdot. Apparently, though, we signed a release, and gave her our address in Hull, because one day a few months later a book of photos, Girls Are Powerful, showed up in the post. We were in it.

I marvelled for a day or two, then I forgot about it again. And now I find out it was part of an exhibit in London. Anita is trying to find the other “lost girls” to reshoot for a where-are-they-now? follow-up. So far she’s found me in the US—I’ve told her about Carol in the UK—and two women in Australia. So if you think you might know any of those long-ago young women, pass along the link. And meanwhile don’t even think about saying I look like Harry Potter…

Also of interest: Anita has embarked on a fascinating project, First Women UK, a plan to photograph—brilliantly beautifully, archivally—100 portraits of women in the UK who were “first” in their field of achievement. The full collection will go on show in 2018 to mark 100 years of women’s suffrage. Here’s video of Anita talking about it.

First Women UK – an interview with photographer Anita Corbin

So if you have ideas about who should be part of the First Women project, or if you think you can help find any of the young women of Visible Girls, talk to Anita.

* I heard from three people I haven’t talked to for more than 30 years…

March 8, 2015

International Women’s Day

International Women’s Day seems like a good time to begin a series of posts about women in the arts, or, more specifically, about discrimination of all kinds in same1. But hey, it’s Sunday, so I’m going to do a nostalgia post instead. It’s a version of a piece I posted a while ago, but, given that I have this spiffy new site and need to play with all its media settings, today seemed a good time to revisit it.

When I lived in Hull, the women’s community—and it really was a community; we were in each others lives to an extent I think most Americans would find amazing, amusing, or appalling—really went to town on International Women’s Day: big parties, blowout celebrations, demonstrations (in every sense).

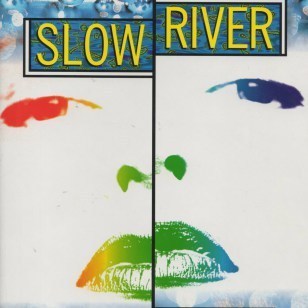

I remember one IWD in particular because it was the day my band, Janes Plane, debuted: 33 years ago today. Just nine months later we were in London, playing at the Ace in Brixton.

Dead Kennedys, The Damned, The Undertones, Cocteau Twins, Killing Joke, Stiff Little Fingers…and Janes Plane. We all played at the Ace that year. (Also, uh, Kajagoogoo, though I will point out that this was before their pop hit, “Too Shy.”)

On December 9, 1982, Janes Plane, the little band that could, found itself on stage one night in front of a sell-out crowd2 and four TV cameras. I had a blast. Sex, drugs, and rock and roll was not a metaphor.

If you’ve read my memoir, And Now We Are Going to Have a Party, you’ll have heard some of the Janes Plane songs. You can read an excerpt about the band’s formation, and how singing brought me to writing, here. Or, ah fuck it, just listen to “Bare Hands”

https://nicolagriffith.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/01-barehands1.m4a

That song was recorded in August 1982, which was also when a UK TV show called Whatever You Want came to town to film us.3 Here’s video of part of that Ace gig. We were woefully under-rehearsed4 and this was the song we’d played least. (It was the last song we wrote; you won’t find it on the CD in the memoir.) Also, Jane’s guitar was horribly out-of-tune. It was always out of tune; even pooling our resources, we couldn’t afford to replace the machine heads.

We were incredibly poor. That white shirt I was wearing cost 20p in a jumble sale and I cut the collar off with a knife—didn’t have scissors. The waistcoat was knitted for me by a lover’s mum. The pink trousers were hand-me-downs that I wore all the time. I was reminded just the other day that on the day of the gig I didn’t have tube fare to get there and had to borrow it. But, hey, we got paid in cash—union rates—right after the show. That night we partied. The only snag is, I don’t remember a thing about it. Eh, I was 22; I thought I ruled the world. I remember that young person fondly.

Enjoy.

1 I’ll be starting that series soon.

2 I’m just guessing but somewhere right around 1,500.

3 You can watch that here. I’m not posting it because the video makes my toes curl. I was 21, trying to hard to look laid back and world-weary, but stressed out about that kitten—you’ll see what I mean if you watch it—and with a wicked hash hangover: the night before I’d smoked Nepalese Temple Ball for the first time; I smoked a lot. Note, too, that my nose looks different: this was two years before I got it broken in a fight.

4 Our drummer left the band not long after the demo recording and the TV filming. She went to London to take a job as a sound engineer for an animated TV programme and we couldn’t find another woman who a) had her own kit and b) could play it. We recruited a couple of guest drummers for a handful of gigs but then the band just…stopped. But, hey, the Ace was in London, so we reformed for one night only. After that gig we could have done so much. But that’s another story…

March 5, 2015

Essay section of the site

I am more amazed every day at just how hamstrung I allowed myself to become by keeping the old ng.com site for so long. (Definitely a case of Perfect being the enemy of Good.) The pre-social media, pre-cloud era design influenced my use. For example, think of all the essays I had listed there. Not all of them, not quite (I’ve written over fifty), but way too many.

I spent yesterday afternoon thinking about how to present essays here and have decided to start small. Half a dozen is probably a good number to begin with. The archived pieces I’ve posted so far are:

Palimpsest — My Review of Jeanette Winterson’s memoir, in which I discuss how Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? is a palimpsest of her first novel, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit; Winterson’s discovery that books are extra-somatic culture; why constraint is necessary for all forms of literature; the way poetry works emotionally; and why narrative grammar is every writer’s friend.

War Machine, Time Machine (co-written with Kelley Eskridge) — The golden age of queer sf is 20. Or maybe it was the 1970s. Or perhaps it was in France. It’s all relative, like the notion of ‘queer’ itself.

Branding: It Burns — According to an Economist review of his posthumous Brand New: The Shape of Brands to Come (Thames & Hudson, 2014), branding is “about knowing who you are…and showing it.” It sounds simple, but, for a novelist, it is not.

The Language of Hild — In which I talk about Old English poetry, the writer’s Black Box, and language—lots and lots of lovely language.

I may or may not rotate them. I may or may not open comments except on brand new pieces. I may or may not turn some of my most viewed posts from the old AN site into essays. I just don’t know yet. For one thing, I’m not sure there’s any meaningful distinction between an essay and a blog post anymore.

Tell me what you think, tell me what you’d like to see: a rotating list of carefully curated pieces, an encyclopaedic list, old posts as essays (things like Who Owns SF? and Lame is So Gay and my Writer’s Manifesto, for example), or some option I haven’t thought of.

March 3, 2015

A reminder: no blurbs or signal boosts for a while

A reminder: I’m not reading other people’s work right now for blurbs; I’m not signal boosting; I’m not coming to your library/school/bookclub/radio show to chat. Sorry. I’m not doing anything, really, except having a life and working on Menewood.

Here’s why, with more details.

March 2, 2015

New and shiny website

With any luck, this will one of the last* posts on Ask Nicola and the first new post of my brand new web site. The previous design went up 13 years ago, created before blogging software. It was the kind of thing one had to lick clean w’ tongue code by hand, definitely uphill both ways a pain in arse. It's why I started this blog here on Blogger in the first place—as a temporary solution. But, well, seven years later...

So, I’ve been meaning to do this for years. There was always something more urgent in the queue. Last autumn, just before I embarked on the Hild tour, I'd had enough. I drew a dozen delicious wireframes for a site would do everything exactly the way I wanted it to.

Then it became clear to me just how much work it would be to actually make happen. For one, it would require a custom design and build for which I do not—have never had—the skills. I don't have the kind of money to pay market rate for someone good enough, either. And those friends I do have who could do this for me, well, it wouldn't be fair to even ask. (We're talking a lot of work.) Besides, even if a friend had been willing to labour over it for an age, it was so close to perfect (in my love-starred eyes) that I would have got completely lost in getting it exactly right. That kind of obsessive fussing can't co-exist with writing Menewood. And even if it could, that would be only the beginning; once the mad and beautiful site was built then the real hassle would begin.

WordPress won't host custom-made themes (only its own themes, customised). Building the perfect site would have meant self-hosting, which, fine, I've done for years, only now with endless, thankless backend update drudgery on top. So I thought, Ah, fuck it! and chose a theme: Studio.

That was three days ago. At which point a good friend began to customise it for me. (All photos are, of course, by Jennifer Durham.) And on Saturday night, after a lovely dinner (there might have been wine...) I looked at the dev site and thought, Even unfinished it's a billion times better than my lumbering Mondrian-esque monstrosity! In other words, again, Fuck it! And we went live. Mostly. (It won't propagate everywhere immediately.)

So here it is, still under construction. You will see changes over the next wee while; don’t be alarmed! Meanwhile, please point your feed readers, bookmarks etc to:

http://nicolagriffith.com/blog/

Soon I will discontinue Ask Nicola. It’s served me well. The Mondrian Monstrosity served me well, too. But, oof, it should have been retired a decade ago.

Questions? Comments? Leave them on the new blog.

* I've imported all these Blogger posts to the new WordPress site, but all the links will, I assume, be screwed. So I'll keep this one up for a while, but as I'll be updating from the new site this could get a bit dusty...