Nicola Griffith's Blog, page 25

May 22, 2023

Charlie and George are 4

Charlie and George had their birthday while we were attending the Nebula conference, so we’ve decided to celebrate today. Here is Charlie explaining his year in interpretive dance.

“It was awesome!”

“It was awesome!” “There were raccoons but I *punched* em!”

“There were raccoons but I *punched* em!” “And then it was spriiiing!”

“And then it was spriiiing!”According to the vet he is a “Fit young cat.” He weighs about 10 pounds, a very sinewy 10 lbs under that deliciously soft and fuzzy fur. If I hadn’t held him and fed him and flinched every time he ran into a wall he couldn’t see after his brain injury three years ago I might not believe that ever happened. He’s happy, healthy, very fit. He’s always doing, always investigating, always leaping up and dashing off. For Charlie, Year 4 was a good one.

Year 4 was also most excellent for George, too, though he is more cautious about expressing it. Though he’s always been bigger and stronger than Charlie he’s also always been much more cautious. He does not like change. At all. He still won’t eat cat food rather than kitten food, and he refuses to accept that his cat tree platform is too small.

“No, no. It still fits.”

“No, no. It still fits.”He weighs his choices carefully. He likes to consider options—very much a thinker first. While Charlie in repose has what we describe as Resting Demon Face, George has Resting Sad Face. But he isn’t sad. He’s just pondering imponderables. My guess? He’s writing a philosophy book.

“Be glad you don’t understand the things I have seen…”

“Be glad you don’t understand the things I have seen…”He is a big cat. Last time we took him to the vet he weighted a hair under 13 lbs. The vet was surprised: she thought he would weigh more given his length and height. “But it’s all muscle,” she said. And it is—he’s heavily muscled and his bones are thick and dense. His affect is slow and deliberate but take it from me he’s wicked smart and very fast. I’m sad to report that earlier this year he caught and ate a hummingbird. (We’ve since moved the feeder to make this less likely.)

He will sleep with Charlie, and, like Charlie, he is very affectionate with me and Kelley. (Every other being on the planet, two legged and four, is either hidden from or hunted.) Unless he’s ill, though, he will never sit on a lap except mine, and then only in bed. Oddly, Charlie will never sit on a lap in bed but loves draping himself all over us any other time (Kelley more than me—she sits more still). When they’re not on us, they tend to stay near us when they’re home. In bed, they both tend to sleep snugged-up next to—but not on—Kelley (because she likes to sleep warmer then me so adds a fuzzy blanket to the duvet—also, she sleeps more and so disturbs them less).

George sleeps

George sleepsThey go through phases when they can sleep companionably together and phases when they can’t seem to bear each other. And then times when you can just tell each is biding his time…

“No, no, nothing’s about to happen here…”

“No, no, nothing’s about to happen here…”They have developed routines. Kelley—working largely on East Coast time because of her dayjob—feeds them early while I’m still in bed. When I get up we let them out—it has to be fully light but that timing varies by season. They’re out for about 20 minutes, then George comes in as I’m eating breakfast, jumps up, gives me a perfunctory head bump, jumps down and positions himself for a quick game of chase-the-treat. Then he’s outside again. A few minutes later Charlie comes home—he blasts through the cat door like a clash of cymbals—jumps up, gets a head bump, a purr and a rub, magnanimously permits me to hand feed him four or five treats one at a time. (They are spoiled.) Then, blam!, outside again. Rinse and repeat in various combos for the next hour or two—including yowls (George) or trills and chirrups (Charlie) if I’m not in the kitchen to provide treats according to their preference. When I’m really focused and working I ignore them (they are not that spoiled); otherwise it’s a good excuse to get up and wander into the kitchen.

Right around midday they come in together, sharking about the kitchen like fuzzy velociraptors. They accept more treats then stuff themselves to bursting with actual food. At this point, depending on the weather, sometimes they nap, sometimes they want to play, sometimes they go back out and start slaughtering (sigh).

Just in the last year or so they’ve reliably settled into an average nine-to-five workday. In winter this shrinks to 10-to-3 and in spring and summer can stretch from 7-to-8. But they are home, with us, cat door securely locked and portcullis down, every night when it gets full dark—except for a brief, two- or three-week period in late summer when George wants to roam and can sometimes stay out until midnight. No one (except George) enjoys this phase. But he does always come home and we’ve learnt to accept it and be grateful it’s self-limiting.

So, bottom line: Charlie Bean, aka Best and Brightest, and Handsome George, aka Murgatroyd, are fit, healthy young cats at home in their world. Life, they tell me, is good.

I’m not really bothering to do Kitten Reports (there are about two dozen of them now) anymore but do occasionally post pix on Instagram or Twitter. Meanwhile, if you’re new to the Toothsome Twosome, check out the link to catch up.

May 19, 2023

Nebula Awards Weekend

Me at the Nebula Awards Red Carpet—in reality a kind of nasty beige—just before the banquet and ceremony. Photo by Richard Man Photo

Me at the Nebula Awards Red Carpet—in reality a kind of nasty beige—just before the banquet and ceremony. Photo by Richard Man PhotoSpear didn’t win the Nebula Award for Best Novel—but I hadn’t expected it to, so I wasn’t crushed. Disappointed? Oh, yep. Winning is always fabulous! But it’s really not a problem for me when the award goes to a good book written by a fine person, which is what happened this year (Babel, by R.F. Kuang). Actually, I would have been fine to lose to any of this year’s finalists.

Best of all, Kelley and I had a fabulous weekend, reconnecting with people we hadn’t seen for years, finally meeting in person those I’ve been talking to online for a while, and meeting brand new people. It was a really diverse crew this year in terms of age, experience, background, identity, and art form. The hotel had a lovely courtyard with plenty of tables so you could choose sun or shade for conversations, and if you just wanted to chill lots of pretty flowers to look at and singing birds to listen to. All just a 20-minute drive from the airport.

One unfortunate thing: lots of people gave me business cards so that I could text or email when I got home but, er, my little stack of cardboard seems to have vanished somewhere between here and there. So if we chatted and you gave me a card and I promised to get in touch, please email or DM me. Yeah, I’m a dimmock—it’s been so long since someone’s given me a business card that I sort of forgot how to deal with them.1

Anyway, here’s a photo of the finalists who were there in person (many more attended virtually). I talked to most of the people in the picture at some point or other (and if I didn’t: Next time!). And today, just as I was about to post this I realised that, for the first time, I was easily the oldest person in the group. I don’t generally think about age much but, wow, that realisation was an interesting moment…

Finalists for the 2023 Nebula Awards, taken in Anaheim, CA by Richard Man.

Finalists for the 2023 Nebula Awards, taken in Anaheim, CA by Richard Man.1 Pro tip: take a photo of them immediately! I mean, I *know* to do this. But for some reason I just…didn’t. Oh, well.

May 11, 2023

Hild’s totems and banners

Over on my research blog I talk a bit about visible tokens of allegiance among armed groups, and make some guesses of the kind of thing Hild’s people in Elmet might have carried into a fight.

Lot of hand-made pictures!

May 3, 2023

Nebula Conference and Awards Ceremony, May 12-14

Kelley and I will be in Anaheim from 12-15 May attending SFWA’s Nebula Awards weekend. I’ll be doing one panel and one book signing, both on Saturday. And of course I’ll be at the awards banquet on Sunday, and any and all of the receptions and parties. And when I’m not at those, I’ll probably be in the bar. So please do come and say hello! I haven’t been to an in-person Nebula weekend for nine years so I might not know your face but I’ve probably read your stuff and I’ll definitely want to meet you—so come and say hello!

About the book signing. The books will be supplied by Octavia’s Bookshelf in Pasadena. I’ll sign whatever you bring—tatty old paperback or glossy new hardcover. Octavia’s presence is being billed as a ‘Pop-Up Bookstore’ so I’m guessing their inventory will have to be pretty focused. Which might mean they’ll be bringing mostly recent and/or best-known books—but that’s just a guess, so if you want to buy a relatively obscure book of mine and get it signed you might want to check with Octavia’s beforehand that what you want will be available.

Autographing Session

— Sat 10:00 – 10:30 am

— Anaheim, signing table A

Career Metamorphosis: Shifting or Expanding Genre, Formats, or Focus as a Writer

— Sat 4:30 – 5:30 pm

— Anaheim in-person and streamed

— Walt Boyes, Sarah Branson, Erin Roberts, Nicola Griffith

“Writers who have successfully changed or added to their original areas of focus (e.g., going from novels to short stories or vice versa; going from writing for kids/YA to adult or vice versa) discuss their experiences and challenges and offer advice for other writers looking to transform or expand their own writing endeavors.”

I’ve no idea what I’ll talk about—hey, that’s what moderators are for—but I’ve made a lot of gear changes over the last few years—in terms of fantastical genre and not, series vs standalone, and short books and monster books. But also there are more nebulous things like being positioned differently by different publishing imprints, the perils of publishing a three-book series with three different publishers, and even more subtle choices like whether to make the Othering of a protagonist overt and explicit or simply Norm that Other. Hopefully it will be an interesting conversation.

April 29, 2023

Spear is a Locus Award Finalist

FANTASY NOVEL

The Grief of Stones , Katherine Addison (Tor; Solaris UK) When Women Were Dragons , Kelly Barnhill (Doubleday; Hot Key) Spear , Nicola Griffith (Tordotcom) The World We Make , N.K. Jemisin (Orbit US; Orbit UK) Nettle & Bone , T. Kingfisher (Tor; Titan UK) Babel , R.F. Kuang (Harper Voyager US; Harper Voyager UK) Nona the Ninth , Tamsyn Muir (Tordotcom) The Golden Enclaves , Naomi Novik (Del Rey US; Del Rey UK) Fevered Star , Rebecca Roanhorse (Saga; Solaris UK) Siren Queen , Nghi Vo (Tordotcom)Locus announced their Top Ten Finalists last night. Spear is a finalist in the Fantasy Novel category. I am smiling.

If you go read the whole Locus Award Top Ten Finalists list you’ll see that fellow Ray Bradbury nominees Ray Nayler and Alex Jennings are finalists for First Novel and Horror respectively, and fellow Nebula finalists Ray Nayler (again!) and Travis Baldtree (First Novel) and T. Kingfisher, Tamsyn Muir and R.F. Kuang (Fantasy Novel) are there, as are two writers who blurbed Spear, John Scalzi (Science Fiction Novel) and Alix E. Harrow (Novella and Novelette).

Winners will be announced June 24 in Oakland.

April 28, 2023

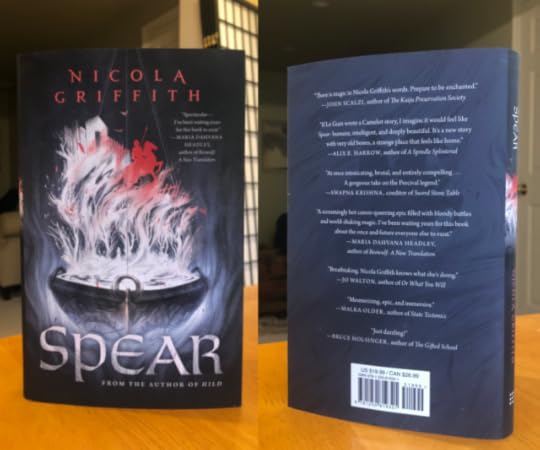

Spear’s first year #4: Beautiful Process ➔ Beautiful Book!

The three best-designed trade novels of mine (so far)1 are Stay, Hild, and Spear. They are all very different, but what they had in common was a smooth publication process, an efficient, transparent workflow overseen by editorial, design and production departments working in tandem to make the story and the package it is presented in match in terms of seriousness and heft. And the most important part? Communication: everyone knowing who is doing what and when, and consulting every step of the way.

When I sign a contract the first thing I tell an editor is that what makes me happy is information. An informed author, a consulted author is a happy author. I tell the editorial, publicity, marketing and sales teams—I rarely have contact with production, sadly—that I need information. All the information—the buzz, the scuttlebutt; the yeses and nos; the good numbers, the bad numbers—and, most of all, a workflow calendar. This really matters to me: I need to know schedules for copyedits, proofs, ARCs, bookseller letters blurb deadlines, finished copies… All of it. This is important for any novel; it’s doubly important for huge, linguistically complicated novels like Hild or Menewood.1

Why? Because I need more planning time than most writers: I have MS. Disability and chronic illness are in and of themselves part- to full-time jobs. Add to that the lack of energy reserves and I simply can’t always just turn a copyedits/proof/publicity plan around in 5 days. I need to plan my energy expenditure. And the last two years I also have another part- verging on full-time job: family responsibilities.2 The math barely works with careful planning; with no planning all is chaos.

For the last two decades I’ve worked with one editor, Sean Macdonald. We’ve moved together from Nan A. Talese to Riverhead to Farrar, Straus and Giroux (and now FSGxMCD). I know what to expect. Mostly. (No relationship is perfect.) But Sean did not think he was the right editor for Spear, so he suggested an unusual editorial/production partnership with Macmillan sister imprint Tordotcom: One of his new MCD editors, Lydia Zoells, was a historical fiction and Arthurian geek so she would edit, and Tordotcom would handle production and publication.

I was a bit wary—”Change is, of course, to be deplored”3—but also aware that this was an opportunity to finally bring together the two parts of my writing life: the SFF of Ammonite, Slow River and every piece of sort fiction I’ve ever published, and the novels I’ve written in the last 25 years. I was cautiously optimistic.

And it turned out brilliantly. I had my first meeting with Lydia and explained my optimal work environment: give me everything, all the time, immediately, good or bad. And—wonder of wonders!—she believed me. Within a week she was passing through to me all the info I needed. Then I had a meeting with Tordotcom—one of those meetings where there are so many people you can’t get all the tiles on your screen at once—and, again, wow! they listened!

It was great—just as it should be. I was consulted and informed every single step of the way. No one had to get grumpy at anyone about anything because there were no surprises. (Publishing is like surgery: You never, ever want to hear someone say, “Uh-oh…”) As a result Spear (like Hild, like Stay) is an integrated whole whose exterior packaging reflects the story within. And the marketing hit exactly the right tone. It worked beautifully. As a result, Spear is a beautiful book. (Let me be clear—though I love Spear and think I wrote a fine book—from her on when I talk about the beauty and fabulousness of Spear I’ll be talking about the physical object, not the words inside.)

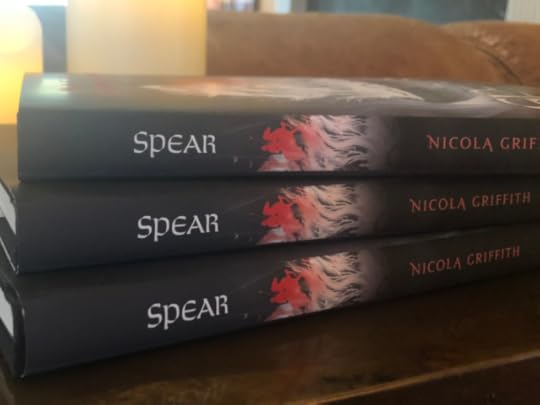

Spear is a very handsome book. In the design department it punches way above its weight. Obviously it looks fabulous—and I’ll talk more about that—but what really struck me when I first picked it up is how it feels in the hand. The jacket has a seriously matte, tactile feel, with a little process on my name and title—not a lot; it’s subtle, just enough to feel substantial. But what’s really lovely is the size and weight.

When I was a teen I preferred reading library hardcovers; paperbacks were okay but they felt flimsy. Over the years, though, I’ve found my preference changing to trade paperbacks and I realise it’s a size issue. Many modern hardbacks are massive and heavy, too unwieldy for comfortable reading unless you have big hands, which I don’t.4 This book is perfect! I could hold it for hours—which of course no one needs to because it’s only 184 pages long. Given its length I worried the book might feel too thin, but look: it’s beautifully proportioned. And the spine of the jacket is very attractive. (Whenever I hold it I just want to stroke it.)

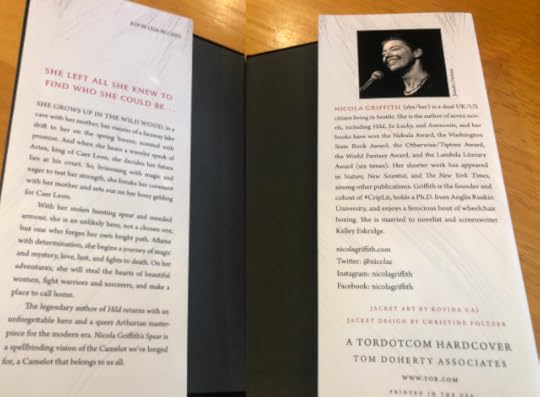

We’re always told not to judge a book by its cover but, hey, we all do. (The cover art is by Rovina Cai and design by Christine Foltzer. I talk about the cover in the cover reveal here and at greater length in a discussion of its conception and execution here). But I can tell you, this book just gets better and better the more you explore.

The front flap is nice—nothing massively special but nice. Ditto the back, and here I’m pleased by the colour coordination: Black and white photo with black end papers; red titles to match the red title and author name on the front. And of course the flaps make perfect bookmarks when you pause mid-read:

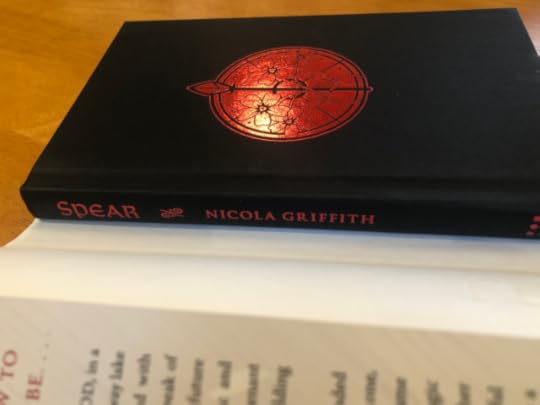

But it’s when you start to take the jacket off that you start to get a sense of the glories within:

Just look at that foil stamping—see how it glows! You can see the individual rivets on the shield. The spine is shiny, too, but I couldn’t get as good a picture of it.

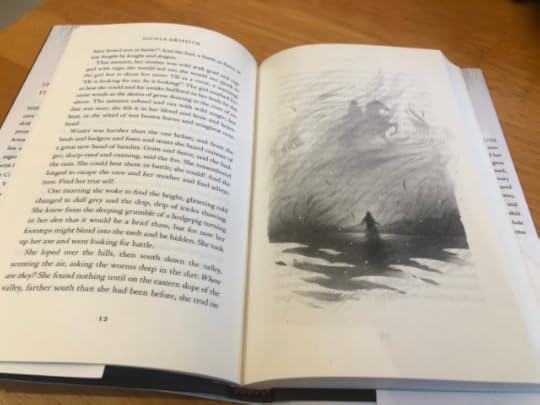

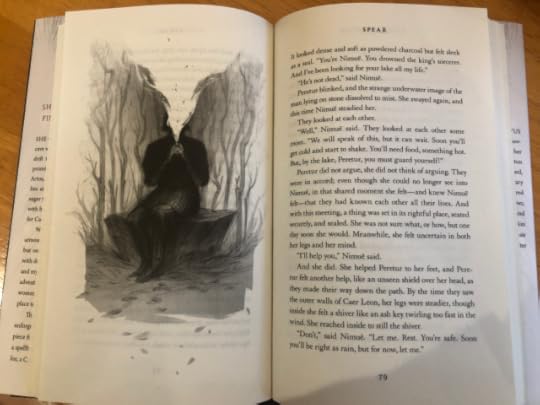

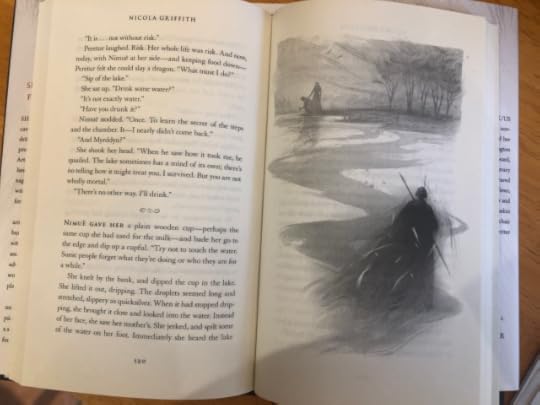

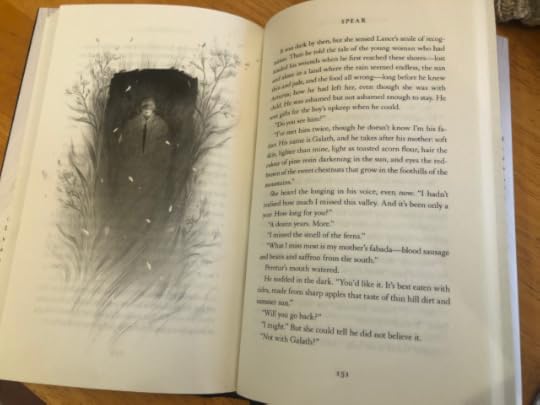

Then there are the interior illustrations by Rovina Cai, five altogether: the perfect moody complement to the text. I’ve put them in a slideshow in the order in which they appear in the book:

The whole book is a design delight, exactly what a hardcover should be. The ebook also looks nice, of course—and the audio sounds good (even if I do say so myself)—but for me there’s nothing like the tactile, memory-evoking joy of a real book: the heft of it in my hand, the sense memory of where a particular moment appears on the page, and the specific weight in one hand vs the other that tells you how far through the book you are when it happens. Plus, of course, you can get physical copies signed by the author.

Tordotcom did a beautiful job with Spear. If and when there’s another installment in the lives of Peretur and Nimuë I hope that comes in just as lovely a package.

IndieBound | Amazon.com | Bookshop.org | Barnes & Noble | Apple | Amazon.co.uk

[1] Hild and Menewood between them are longer than The Lord of the Rings—and uses at least as many languages, and those languages are changing all through the text. The way a word is used at the beginning of Hild is not necessarily the way it’s used at the end. Do you have any idea how much time it takes to get those copyedits right? AndI don’t count And Now We Are Going to Have a Party, my memoir, because that design is a whole other, amazing thing: a signed and numbered limited edition boxed collector’s set. I don’t count And Now We Are Going to Have a Party, my memoir, because that design is a whole other, amazing thing: a signed and numbered limited edition boxed collector’s set. And of course Menewood is yet to come…

[2] My sister in the UK has serious mental health issues; emergency phone calls and consultations in the wee hours are not unusual. Kelley has two sets of ill and ageing parents who have no one else to rely on. And of course we have two cats who have both already nearly died twice

[4] This, apparently, surprises people. Perhaps because I have big shoulders and muscled arms people expect big shovel hands at the end of those arms, but, no; my hands are small.

April 27, 2023

Spear’s first year #3: Rich research, circular as the seasons

An imaginary moment in which three seasons coexist: blossom in spring, green green grass of summer, and the falling leaves of autumn—blending and never-ending, like research.

An imaginary moment in which three seasons coexist: blossom in spring, green green grass of summer, and the falling leaves of autumn—blending and never-ending, like research.Image description: A book, Spear by Nicola Griffith, standing upright in the grass under the trees. Against it lean an enamel pin, sized to look like a shield, and a large boar spear. A small hedgehog noses through the grass at lower left. It could be spring, summer or early autumn.

Over on Instagram, OliviaKRobinson asks;

I was struck by how incredibly rich and well-researched the world of Spear felt – what sources did you use to develop and research it?

Much of the foundational early-medieval research—the things I need for world-building: language, archaeology, climate, material culture, agriculture, etc—I’d already done1 in service of Hild (2013) and Menewood (October 2023). And those sources are so numerous and spread over so many years—many before I started keeping track of my sources—that I wouldn’t really know where to start.2

Much of the Arthuriana, in all its (almost) infinite variety, I’d absorbed by osmosis over the years, first through story—everything from Mallory to Tennyson to Sutcliff to Treece to Stewart to Bradshaw—and then through the sources I encountered in those books’ paratext.3 For example, when I first read Mary Stewart’s The Crystal Cave in my late teens/early twenties, I read her Author’s Note and encountered for the first time mention of the Historia Brittonum (HB) by Nennius (or, as I discovered many years later, the ‘Nennian compiler’). In the course of researching Hild I discovered that Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (HE) probably relied to an extent on De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (DEB) by Gildas—but possibly also on a lost source referred to as the Northern Memorandum. Which turned out to perhaps also have been part of the inspiration for HB—as were DEB and HE. I was beginning to figure out that much of what we think of as history has no definitive source, just endlessly circular references and revisionist interpolations. For a while I thought everything we thought of as history was actually just legend, or even myth. It was at that point that I gave up history and relied instead of archaeological research and material culture. Only to discover that this was often interpreted through the lens of standard historiology.

Round and round with no beginning. (Maybe you’re beginning to understand why there’s no simple answer to an apparently simple question.) Don’t get me wrong—I absolutely love this stuff! It’s my crack. I can get so lost in tracing the connections that I forget why I was researching in the first place; the research becomes its own purpose and joy.

Anyway back to Spear. When I first pondered the possibility of working with Arthurian legend I was in this liminal space: poised between the absolute knowledge that it couldn’t be done—that nativist, supremacist Manifest Destiny was essential to what makes the legend so attractive—and the dawning realisation that there was…something, some tiny clue glimmering in the mist if I could only get to it… And the etymological research I’d been doing in service of place names was part of it.

I’ve been writing fiction long enough to understand when a thought, and idea is so delicate it has to be ignored for a while so it can solidify. So instead of running down the etymological link I started thinking about the Matter of Britain and how it has been used as a rationale for English/Anglo-Saxon/Germanic supremacy for almost a millennium. And that’s when I started thinking about legend and its relation to myth, about cosmology, eschatology, and ontology. I read all sorts of seriously odd stuff that was part philosophy and part religion with a dash of lit theory which led me in circular fashion (this research always ends up being circular, repeating as endlessly as the seasons) back to Tolkien’s notions of myth and story. At which point I felt I’d reached a precarious balance that would topple if I added one more thing, so I sat back, left everything mulch in that black box that is the writer’s subconscious, and did something else (I wrote some more Menewood).

And then one day the vision of a rider on a bony gelding emerging from the mist, both exhausted, both wounded, the rider in tattered and mended armour and holding a red spear, and Boom! it all came together: I could see how Arthurian legend had to end the way it did in order to create its own beginning, and that the rider was Peretur, that I could set this story in the sixth century and, through the person and name of Peretur herself, could tie together Welsh history, English legend, and Irish myth and absolutely fucking destroy that rich white straight nondisabled male Manifest Destiny crap.4

So my sources? Everything I’ve ever read and loved and hated, everything I’ve yearned for and wanted to change. Will it change the world? No. Might it crack the legend open just enough for others to enter? Maybe a little. But if the only real result is one small book that pleases me very much, that’s enough.

[1] And am still doing

[2] It includes all stages of early-medieval (or ‘Anglo-Saxon’ or even ‘Dark Ages’) historiography starting with early to mid-20th century standards such as Trevelyan, to Stenton and on, through the archaeological emphasis in the 70s, to popular TV shows like Time Team to cultural histories to Big History and now to academic pre-prints and conference papers and—importantly—research blogs. If I could somehow go back in time and take notes, I have no doubt the working bibliography would run to several hundred pages. But it also includes constant current research into the natural world: which trees flower first? What do hedgehogs eat? When do certain birds migrate?

[3] Paratext is just a fancy term for the fiddly bits, the delicious extras some writers generously include with their novels: the Author’s Notes about history, historicity, process, and so on; maps; glossaries; family trees…

[4] Insert emoji of writer standing on her desk, head tipped back, positively yodelling in triumph.

April 26, 2023

Spear’s first year #2: Page and voice

On left, reading Spear, photo by Kelley Eskridge, and on the right, reading So Lucky, photo by Eric Johnson

On left, reading Spear, photo by Kelley Eskridge, and on the right, reading So Lucky, photo by Eric JohnsonImage description: Two photos of the same short-haired white woman sitting in front of hideously expense-looking microphones in two different sound studios. On the left, she wears a grey cashmere sweater, headphones around her neck, and is looking directly at the camera. On the right she sits before an iPad placed on a music stand which is covered with sound-deadening old carpet. To one side is a wheelchair and a small table. She’s wearing headphones and a tee-shirt printed with a tangle of charging cords that look like an electric jellyfish, and is looking to one side at someone off-camera.

In a comment Simon asks:

Something I found very special about Spear was listening to you voice the audiobook. I seem to remember you saying in an interview or maybe here on your website that you pushed hard to be the audiobook narrator. To my ears at least, you were wonderful to listen to, and your thoughts on reading to your audience would be great to hear

And over on Facebook Cat asks:

How was that audiobook narration experience? Would you do it again?

The short answers are: fabulous, loved it, and absolutely. But I’m guessing you’dlike more detail.

I’ve narrated two of my books now, So Lucky and Spear. Both times were great experiences, but in very different ways. So Lucky was my first time (read Recording the So Lucky audiobook for more on that) whereas with Spear I felt confident.

What follows is a lot of detail (taken from other blog posts)—but if detail isn’t what you want, skip directly to the section labelled ‘ ‘All the Feels’.

Detail: PREPRODUCTIONWith So Lucky, set in contemporary Atlanta, I didn’t have to worry about pronunciations or (with one exception) accents. Spear, on the other hand, is set in 6th-century Wales, with Primitive and/or Old Welsh (standing in for Brythonic), Primitive and/or Old Irish, and Asturian dialogue, names, and general vocabulary, not to mention the Old French, Middle High German, and Old English words in the Author’s Note.

I decided early on that there was no point trying to figure out how real really early Welsh would have sounded, so I substituted modern Welsh. Ditto for Primitive/Old Irish to modern Irish. The Astures of northern Spain supposedly used a p-Celtic language very similar to Brythonic, so for that accent I just used a very light and precise version of modern Welsh (much as a northern Spaniard fluent in modern English might sound today). Then I made a list of words and phrases I’d have to get right; it came to 73.

So then I sent the list to the Macmillan producer and said, Help! Three weeks later I had over seventy individual sound files of flawless pronunciation from native speakers. I listened to them over and over, until I was confident I could pronounce them correctly. Then (because I’m not familiar enough with the IPA—International Phonetic Alphabet—symbol system) I had to figure out my own system of writing them down phonetically.1 Here’s what that looked like:

Then I started marking up the text itself. Here’s an example of the markup of an early page.

However, just because I know precisely how to pronounce a thing doesn’t mean that I should. To take a modern example, the French pronunciation of Paris sounds perfectly fine when a Frenchwoman in France is using it, but if an American pronounces it that way during a conversation in a sports bar it sounds ridiculous. And of course working folk never pronounce things the same way nobility do—every class has its own accent. How then would a 6th-century Greek quartermaster/military logician speaking Welsh pronounce something? Or a Briton with a northern accent? On top of that, I had to think about how to differentiate people of the same class, and then fold gender into the mix. It all took a while to sort out but by the time I arrived at the studio I was ready!

Except, of course, no plan survives contact with the director…

Detail: RECORDINGWhen you narrate an audiobook it’s not just you and a microphone. It’s you in a locked, soundproof room before a microphone, with an engineer in the mixing booth behind glass, and a director from New York on Zoom audio—with all three audio feeds mixed into your headphones. The engineer for this project was Joel Maddox. His job was to make sure I sounded good—to use the right microphone in the right position and hooked into the right interface at the right setting; to point out and note on his iPad for the editor if he hears any extraneous noise—weird feedback, a belly growl, clicky mouth noise, a faint thud of my hand pounding on my thigh during an emotive moment (oops)—and to note, too, whenever I stopped.

My director was Caitlin Davies. I think I was pretty lucky to get her. She’s not only an award-winning voice actor and narrator herself but also a theatre director and a very experienced audio director—her work has been nominated for and won a variety of awards. I learnt a lot. The book you will eventually hear will be orders of magnitude better than anything I could have done on my own.

The first thing we did was decide on method. There are two basic ways to record narration. One is free roll, where the narrator just reads, stops when they make a mistake, back up to the nearest clean punctuation break—a full stop, a comma—and starts again, all without stopping the recording. The other is punch and roll, which is to actually wind back the recording to the bad word/phrase (doesn’t have to be punctuated) and punch in to record at the right moment. I plumped for free roll: it’s quicker, easier, and much less tiring.

On that first Wednesday, I began pretty confidently and we rolled along seamlessly—until Caitlin said, Good, now you’re in it. Let’s go back to the beginning. Give me a storyteller’s voice. I thought I had been. I tried again. Faster, she said. And then *click* there it was: That smooth, warm, lean-in-and-listen note I realised had been missing. And now I was excited! This was going to sound awesome!

We cracked right along. Then we started getting to multiple character voices. I’d spent some time figuring out accents and tones and weights to differentiate people—only it turned out Caitlin thought some of it didn’t work, particularly the women. So I had to go back and work out different voices. It was a bit unsettling; I wasn’t sure these women sounded the way I imagined them. But Caitlin was the director with the vision, so I followed her lead.

The rest of the session went well. The only problem was the heat in the studio, or lack of it. By the time we finished—at 1:00 pm, ahead of schedule—I was frozen in place. My hands were purple and my leg muscles utterly spastic. I asked Joel to please, pretty please crank the heat early the next day so it would be warm when we began. I went home full of energy.

Thursday was hard. The studio was warmer, but every time I read a couple of sentences my voice would crack and scratch and I’d cough. It turned out the heat had kicked up dust and other particles. I’m wicked allergic to dust, also to tree pollen, and February is the start of pollen season. Day Two was sheer bloody stubbornness on my part, and patience and sympathetic-but-hard-task-masterliness on Caitlin’s. Again and again she said, No, go back to the beginning of the paragraph, and I would. Or, Now go back to the beginning of the scene, with more energy. And I did. The last page took fifteen minute because I could hardly manage a phrase without coughing. It was brutal. By 1:00 pm I was toast; I couldn’t read another sentence.

Because of a conflicting gig on Friday—I was delivering Opening Remarks for the Annual Historical Fictions Research Network Conference in Salzburg—we had scheduled a 3-day break from recording and planned to return on Monday and finish Tuesday.

Monday I went in wondering how it would go: brilliant, like Wednesday or brutal, like Thursday? It turned out to be brilliant: fast, smooth, easy, and exciting. It felt as though we’d hardly started when *boom* we were done. It was only 12:30. As I blinked and shut down my iPad, Caitlin warned me there might have to be a pick-up session once the editors had worked on it and found those swallowed words or odd noises the three of us in the studio had missed. But, woo hoo, I was done! I was tired but happy.

All the feelsI finished recording Spear at lunch time on a glittery bright day, and despite Covid Kelley and I decided to risk going to the pub for a pint—my first pint of Guinness for four months. It tasted wonderful and I felt wonderful. So I had another.

It’s hard to describe how reading this book felt. It would be easy to say it felt Amazing or Marvellous or Wonderful, and it would be true, but it’s not the whole story or perhaps not the real story. Reading Spear felt right. It felt sure. It felt as though it was meant to be. Am I the world’s best narrator? No. Am I the world’s best narrator for this book? Yes.

From the moment I wrote the first sentence of the story that grew into Spear I knew this book was different. Each sentence purled out, free and joyous, absolutely and unselfconsciously one with itself. It felt almost ecstatic, as close to a perfect writing experience as I might ever get. I knew how it would feel to read it aloud, how it would sound. It felt incantatory, and there’s something about the particular rhythm matched to the kind of words I was using to try to evoke the living wildness of nature that… Ah, and now this may well sound extreme—overboard and possibly even grandiose—but if you really want to know how it felt to read Spear aloud to an imaginary audience then you’ll just have to accept it: it felt like worship. I don’t mean adoration and obedience but that feeling you get at a huge arena gig (or, yes, in a full church) when the whole crowd is swaying and singing and giving it up, giving over solitariness and apartness and riding the sound of the human voice up, up into a communion of love and joy offered, received, shared and multiplied. That’s what it feels like—a communion. And that’s what finding just the right words to tell a story feels like, too, that possibility that someone you’ve never met—in a place you never been, and perhaps during a time you will never live to see—will one day read what you wrote and so know what you knew and feel what you felt. And that, when it comes down to it, I why I do this thing.

IndieBound | Amazon.com | Bookshop.org | Barnes & Noble | Apple | Amazon.co.uk

1. My system wouldn’t work for others. For example I know in this context that when I write -alk, it means to use the guttural sound a bit like the one that comes at the end of loch, or the beginning of Hanukah—because /x/ wouldn’t mean much to me in the moment—though perhaps no one else would.

April 25, 2023

Spear’s first year #1: Wild Magic

Questions and requests related to Spear are beginning to trickle in on various platforms. If you have a question, drop a comment. Meanwhile here’s one from Facebook:

I loved Peretur’s detailed and concrete connection with the natural world (I loved that about Hild too) … I’d be very interested to hear about how you conceived that

Stacey B, Facebook

Before I wrote a word of Hild I’d been dwelling in the world of seventh-century Britain for years—researching language and landscape, flora and fauna, weather and wyrd, metal-smithing and military hardware, cloth and culture—building the world Hild would be born into and so, inevitably, the world that had given birth to that world, that had come before: the sixth century. Peretur’s world. For years as I read and dreamed I wasn’t thinking about plot, and not much about character; I was building—one stream, tree, horizon, winter, and bird at a time—the worlds they would be born into, the worlds they would interact with and would shape and be shaped by.

Every novel I have ever written—and almost all my short fiction—begins outdoors. It’s just how I think, how I work, who I am as both a human being and a writer. I’m a creature of the body. And any major character I create will be, too. Add to that the fact that both Spear and Hild are set in early medieval Britain: after the industrialised agricultural production of the Roman occupation and before the literate proto-states that followed the Conversion Age. Both Peretur and Hild are born into worlds recovering from at least one major cataclysm—cultural, natural, political—and, unbeknownst to them, heading straight into another. It was a time of turmoil and change, a series of upheavals interspersed with moments of safety and respite. Those who survived lived close to nature: they had to. Guess wrong about planting or harvesting time, about when to take the flock upland, about when to coppice what part of the wood, and you starved. Pay attention or die.

So when you ask me to explain how I conceived of Hild’s and Peretur’s connections to nature, I’m not sure I can. With both Hild and Spear I sat down to write one day and the approach unfurled before me like a path through the glimmering wood. I didn’t stop and wonder whether it was a good path or the right, it was the path, the only path, and it would take me where I needed to go.

In both cases, then, the character’s connection to nature just…was. They live in nature, they swim in it, they breathe it. They are wholly immersed in the natural world and very much in tune with it. And they love it—and therefore love themselves because they feel absolutely part of the world around them. A sense of ownership and belonging. Obligation and gratitude. They might both say nature was their first teacher. They might both say that nature is magical and mystical, ineffable and illimitable. They both have an almost ecstatic relationship with the living landscape.

The big difference of course is that while Hild’s connection to nature appears to be preternatural it isn’t—whereas Peretur’s actually is. Hild is wholly mortal and wholly of this naturalistic, realistic world. Peretur is not wholly mortal but partly of the Overworld and the landscape she moves through runs with real magic. Both books start with Hild and Peretur as children, and by page two we can already make out the difference in how they learn from nature.

Here’s a short passage from the first page of Hild:

She lay at the edge of the hazel coppice, one cheek pressed to the moss that smelled of wormcast and the last of the sun, listening: to the wind in the elms, rushing away from the day, to the jackdaws changing their calls from ‘Outward! Outward!’ to ‘Home now! Home!’, to the rustle of the last frightened shrews scuttling under the layers of leaf fall before the owls began their hunt. From far away came the indignant honking of geese as the goosegirl herded them back inside the wattle fence, and the child knew, in the wordless way that three year-olds reckon time, that soon Onnen would come and find her and Cian and hurry them back.

Hild, p1 (FSG, 2013)

Three year-old Hild feels absolutely at home in nature. She feels part of it, and safe. Living things to her have personalities. She is imagining what the jackdaws are saying, and when she hears the geese she knows Onnen will come soon—not because the geese are actually telling her so but because she’s already in tune with the human rhythms of her community: the goosegirl brings in the geese when the light starts to fail—which is also usually the point at which Onnen comes to find her and bring her home. In the way of smart children of any time and place she is learning to piece together disparate clues, build a pattern, and interpret the result.

Now here’s an excerpt from the beginning of Spear:

She roams the whole of Ystrad Tywi, the valley of the Tywi who fled Dyfed in the Long Ago. In this valley, where there is a tree she will climb it; it will shelter her; and the birds that nest there in spring will sing to her warning of any two-legged approach. In May, as the tree blossom falls and herbs in the understorey flower, she will know by the scent of each how it might taste with what meat, whether it might heal, who it could kill. From its nectar she will know which moths will come to drink, know too of the bats that catch the moths, and what nooks they return to where they hang wrapped in their leather shrouds as the summer sun climbs high, high enough to shine even into the centre of the thicket. Before harvest, when the bee hum spreads drowsy and heavy as honey she tastes in their busy drone a tale of the stream over which they skim, the falls down which the stream pours, the banks it winds past where reeds grow thick and the autumn bittern booms. And when the snow begins to fall once again, she catches a flake on her tongue and feels, lapping against her belly, the lake it was drawn from by summer sun, far away—a lake like a promise she will one day know.

Spear, p2 (Tordotcom, 2022)

Peretur also feels absolutely at home in nature. She feels part of it and safe. Living things have personalities. The difference is that in Peretur’s world, living things do actually talk to Peretur and, as we find out later, she can talk back. In other words, while they both learn from nature, Hild’s learning is mediated by her reasoning, her thinking mind. Peretur’s, on the other hand, are visceral, unmediated, and direct.

Hild loves and feels at home in nature but her gift is the purely naturalistic ability to spot patterns and extrapolate. Peretur also loves and feels at home in nature but her gift is the preternatural ability of a not wholly-mortal being to communicate directly with all aspects of nature—to her everything is alive, not just trees and bats and bees but the wind, the water, the sun on her face.

Did I know all this before I sat down to write either of these books? No. But I knew it by page two of my first draft of each. I hope that answers your question.

Tomorrow: How I feel about narrating the audiobook.

April 23, 2023

Happy Birthday to Spear!

Last week—Thursday 19th to be exact—marked the one-year anniversary of Spear‘s publication. I forgot because I had a lot of other stuff to think about. But I’m proud of my Little Book That Could. And given that Menewood’s publication in less than six months will inevitably push Spear to one side, I thought I’d do a series (3? 5? I don’t know, let’s see where this takes us) of posts to both celebrate what I enjoyed about Spear‘s publication—these might be a little eccentric and certainly all about what *I* liked, not necessarily what the rest of the world might consider important (y’know, to the extent that the world thins about my book at all) and to thank those who made the book and its success possible.

If there’s anything in particular you’d like me to talk about—about the writing, editing, publishing, supporting, narrating, tools and process, or publicising of Spear—let me know in the comments.

I’ll start with what I was doing last spring, a month or so before Spear came out, which was indulging myself making pictures and videos using stacks of ARCs. Getting the ARCs is always a thrilling moment—the first time I really know my chunk of words will be a book, a real book that exists outside my own imagination, that other people will hold in their hands. It’s the moment I understand that soon the world I made and the people I populated it with will no longer belong to me but to readers. It’s a weird mix of exciting and wistful. Creating things peripheral to that world feels good. I had such a good time making them, in fact, that I could post an example every day for a year and not repeat myself. The amount of time spend on each was hugely variable. So, for example, this first video took less than ten minutes, including editing.

Monstrous Good!Whereas the one below took dozens of hours. First I had to take and edit the photo of the ARCs. Then take a separate photo of the shield-and-spear pin and edit that. Then draw the picture of the horse. Then build the composite image with shadows in the right places, a certain colour coherence, etc. Why spend so long on something that makes no difference to sales, no difference to anyone or anything? Because it was fun. Because I liked doing it. Because it’s a good way to learn Photoshop and Procreate. But mainly because when I’ve finished writing a book it can be hard to let the people and places go, and this way I get to stay connected, working in its world, for a little while longer.

This next picture for example, is the direct result of my affection for Bony, the gelding that Peretur rescues, and who in turn teaches Peretur how to ride, and through his bravery—facing a horse much bigger than him—saved her life.

Bony was a warrior…

Some of the stuff I did did have purpose. Here for example is the Zoom background I made for the virtual book tour, designed for good colour balance and with a space in the middle for my talking head. (I ended up not using it very often because setting up the greenscreen was such a hassle. But it was interesting to make.)

Zoom!

And here’s a selection quote tiles I built as both clues for the adjective competition and adverts for the book on Instagram.

Raving…

I could keep adding things all day but I’ll stop here. Tomorrow perhaps I’ll talk about the book itself—the physical object, the design and illustrations (none of the work here would have been possible without the marvellous illustrations by Rovina Cai), and perhaps a bit about how I wrote it, and why, and how it all felt..

If there’s anything about Spear you want me to talk about this week, drop a comment