Mark Rubinstein's Blog, page 18

April 7, 2015

“Black Scorpion” A Conversation with Jon Land

Jon Land is the prolific author of more than thirty-five books. His thriller novels include the C aitlin Strong series about a fifth-generation Texas Ranger, and the Ben Kamal and Danielle Barnea books about a Palestinian detective and an Israeli chief inspector of police. He has also penned the Blaine McCracken series, standalone novels, and non-fiction. Jon was a screenwriter for the 2005 film Dirty Deeds. He is very active in the International Thriller Writers Organization.

aitlin Strong series about a fifth-generation Texas Ranger, and the Ben Kamal and Danielle Barnea books about a Palestinian detective and an Israeli chief inspector of police. He has also penned the Blaine McCracken series, standalone novels, and non-fiction. Jon was a screenwriter for the 2005 film Dirty Deeds. He is very active in the International Thriller Writers Organization.

His latest thril...

March 25, 2015

'The Stranger' A Conversation with Harlan Coben

Harlan Coben has gone on to write eleven more standalone novels. His books regularly appear on the New York Times bestseller list, and more than 60 million have been sold internationally. He was the first writer to receive the Edgar, Shamus and Anthony Awards.

His latest thriller-mystery is The Stranger. Adam Price is an attorney married to Corinne. They have two sons and enjoy a wonderful life, living in Cedarfield, New Jersey. One evening, a stranger approaches Adam at an American Legion Hall. He stuns Adam with the revelation his wife faked a pregnancy, and tells him how to confirm this deception. Soon after Adam confronts Corinne with this secret, she disappears, sending him a cryptic text message. As Adam searches for his wife, it becomes apparent he is enmeshed in something far more sinister and all-encompassing than just his wife’s deception. In usual Harlan Coben fashion, the plot has multiple twists and a completely unanticipated ending.

The plot of The Stranger, like your other novels, is quite intricate with many twists. How do you structure them?

When I start to write, I know the beginning and the end, but I don’t know much in between. I’ve often compared it to travelling from my home state of New Jersey to California. I could take Route 80—the most direct route—but chances are I’ll go via the Suez Canal, and stop at Tokyo. But, I always end up in California.

E.L. Doctorow once said, ‘Writing is like driving at night. You can see no farther than your headlights, but you make the journey.’

Sometimes, I’ll outline one or two chapters ahead as I go along, but generally, I don’t outline.

The Stranger, as do many of your novels, involves someone who’s gone missing. I view you as the Master of the Missing Person. What draws you to this scenario?

A missing person could be alive or dead. There’s hope. I love writing about hope. Hope can make your heart soar, or can crush your heart like an egg shell. For me, missing people ratchet up the emotion. Unlike in a murder mystery, there’s more than justice being served in solving the crime; you can have full redemption when the person is found. I love the possibilities disappearances present.

What do you think makes your thrillers so appealing?

I don’t know. It’s something for someone else to say. I aim to make the story gripping and the characters compelling, without wasting any words. I think the key is the emotional layer beyond simply stirring the reader’s pulse; I want to stir the heart. I try to make the reader really care about what happens to the people in the book.

Your thrillers don’t involve the usual protagonists—soldiers, detectives, lawyers, CIA agents, or spies. They’re about ordinary people whose lives change in a few dramatic moments. Will you talk about that?

I enjoy writing about that sort of Hitchcockian ordinary man who finds himself in extraordinary circumstances. That situation is more compelling and the reader can relate more readily than if the character is some kind of superhero. I want the reader to be immersed in the protagonist’s world, and not be able to leave it. In The Stranger, I want you to be in Adam’s shoes, to feel what Adam’s feeling and thinking. It helps if he’s the kind of guy who lives down the street, and is less classically heroic. I try to keep the reader up all night, wanting to know what’s going to happen.

Do you feel the most frightening things are those that could actually happen?

Almost all my ideas come from something that happens in my regular life. I then think, ‘What would happen if…?’ For The Stranger, I didn’t make up the Fake-A-Pregnancy website. There are sites that actually sell “bellies” and fake sonograms, along with bogus pregnancy tests. That being the case, my mind says, ‘What would happen if someone found out his wife was never pregnant and just faked it?’ It’s basically the real-life ‘what ifs?’ That’s how all my books start.

You once said reading William Goldman’s novel, Marathon Man, was a life-changing event. Tell us about that.

I was fifteen or sixteen. I hadn’t read many adult novels; mostly, I read the classics and school readings. My father gave me Marathon Man. I found myself racing through it. You could have put a gun to my head, and I wouldn’t have been able to put that book down.

While I didn’t try to become a novelist until years later, I think sub-consciously, there was something inside me that said, ‘What a cool job it would be to be able to make people feel the way I’m feeling right now, reading Marathon Man.’

What has surprised you about the writing life?

It’s been a very interesting climb for me. I didn’t hit it right away. I took all the steps along the way—being published by a small house; then by a slightly larger one; then came a bit of recognition; then a little bit more sales; then more, until the last seven novels have debuted as number one on the New York Times list.

I have a true appreciation of how lucky I am. I think one of the surprises is that as a bestselling author, I can still have a normal life with my wife and four kids, living in the suburbs.

What do you love about the writing life?

I think the short answer would be ‘What don’t I love about it?’ There’s no downside for me. I guess I’d rather not have to do so much travelling; and writing never gets any easier. It always torments you. There’s that insecurity, the feeling I’ll never be able to do it again. Unlike some other jobs, you can never, for a second, just show up. But really, for me, there’s very little downside, and I love what I do. It’s been a dream come true.

What would you be doing if you weren’t writing?I have no other marketable skills. I’m disorganized, forgetful, and easily distracted. I don’t know what I would be doing. Frankly, that’s part of what makes me a writer. Writing is a form of desperation. Most writers aren’t capable of handling a real job in society. This is all we have. So, this is what I do.

If you could have any five people from any walk of life, living or dead, join you at a dinner party, who would they be?

Well, I’d love to have my parents with me. If I chose writers, I’d invite those I’ve known personally, who have passed away: David Foster Wallace, Elmore Leonard, Donald Westlake, and Ed McBain. They were writers whose work I admired greatly, and whom I personally admired enormously.

Congratulations on writing The Stranger, another suspenseful thriller whose gripping and intricate plot is completely plausible, and chillingly frightening.

Inspector of the Dead by David Morrell

Inspector of the Dead by David MorrellMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

David Morrell's sequel to Murder as a Fine Art is a thrilling, high-stakes tale about murder, detective work, social class, and very much more in Victorian London. I found this novel even more compelling than the first one. Someone is killing off the elite in London, and Thomas DeQuincey and his daughter become involved in solving the mystery of who is doing this and why it's being done. In fact, as each murder occurs, it becomes evident that Queen Victoria herself is going to be the ultimate target of the serial killer. Written in a style that takes you back to London in the mid 1850s, Inspector of the Dead is one of the best books I've read in a very long time. David Morrell has gone from First Blood (Rambo) to Victorian England, and in doing so, demonstrates his wide range of creative ability with these latest novels.

If you enjoy mystery, suspense, beautiful prose, and an atmospheric rendering of another time and place, this is the book to read.

Mark Rubinstein

‘The Stranger': A Conversation with Harlan Coben

Harlan Coben is known to readers everywhere. His first novel was published wh en hewas twenty-six, and after two stand-alone thrillers, Play Dead in 1990 and Miracle Cure in 1991, he began writing the popular Myron Bolitar series. His 2001 standalone novel, Tell No One, was hugely popular. In 2006, Film director Guillaume Canet made the book into the French thriller, Ne le dis a personne. The movie was the top box office foreign-language film of the year in the U.S.; won the Lumiere (French Go...

en hewas twenty-six, and after two stand-alone thrillers, Play Dead in 1990 and Miracle Cure in 1991, he began writing the popular Myron Bolitar series. His 2001 standalone novel, Tell No One, was hugely popular. In 2006, Film director Guillaume Canet made the book into the French thriller, Ne le dis a personne. The movie was the top box office foreign-language film of the year in the U.S.; won the Lumiere (French Go...

March 24, 2015

‘Inspector of the Dead': A Conversation with David Morrell

After receiving a doctorate in American literature at Pennsylvania State University, in 1970, Davi d Morrell became an English professor at the University of Iowa. In 1972, his debut novel, First Blood was published; and by 1982, was made into the blockbuster movie, Rambo, First Blood, the first in the wildly successful series bearing the iconic Rambo name. David kept writing novels while teaching literature, but eventually devoted himself to full-time writing. He was a finalist for the Edgar...

d Morrell became an English professor at the University of Iowa. In 1972, his debut novel, First Blood was published; and by 1982, was made into the blockbuster movie, Rambo, First Blood, the first in the wildly successful series bearing the iconic Rambo name. David kept writing novels while teaching literature, but eventually devoted himself to full-time writing. He was a finalist for the Edgar...

March 20, 2015

'World Gone By' A Conversation with Dennis Lehane

A Drink Before the War won the Shamus Award. Mystic River won both the Anthony and the Barry Awards for Best Novel, and the Massachusetts Award in Fiction. Live by Night won the Edgar Award for Best Novel, and the Florida Book Award Gold Medal for Fiction.

World Gone By continues the saga of Joe Coughlin, who made his debut in The Given Day, and returned in Live by Night. It’s now the height of World War II. Having lost his wife in a hail of gunfire ten years earlier, Joe is consigliore to the Bartolo crime family in Tampa. He lives peacefully with his son, Tomas, and moves easily among the various underworld figures of the time. Joe finds out someone has mysteriously placed a contract on his life. Trying to learn more, Joe goes on a chilling journey through the black, white, and Cuban underworlds where he crosses paths with the Lansky-Luciano mob, Tampa’s social elite; and also with the mob-backed Cuban government of Fulgencio Batista.

You once said you knew with the publication of A Drink Before the War, you would be labelled a genre writer. You said, "And there's no way out of that, so let's just go all the way. And I'm so glad I did. It's been the greatest accident of my life." Will you talk about that?

I don’t know if it’s still true of me, now, but it was certainly true when I came out of graduate school in 1993. The genre was very much ghettoized. Sometimes it was for good reasons; in some cases it was unfair. What I and others were rebelling against was the notion that literary fiction was literature. It was its own ghettoized genre, or should have been, according to that kind of thinking. I was growing very tired of what a writer once referred to as ‘stories about the vaguely dissatisfied in Connecticut.’ At the time, it was dominating literary fiction. I became enamored of writing about what Cormack McCarthy called ‘fiction of mortal events.’ That’s why I drifted into crime fiction. I think crime fiction has social value, and I was very interested in writing about social issues such as race, class—you know, the haves and have-nots in American society. It seemed like a natural fit with the crime novel.

Now, twenty years later, while we may not have knocked the genre gate down, we’ve stormed it. Some lines of distinction between so-called literature and crime fiction have become a bit blurred. Now, some crime fiction is allowed into the club. (Laughter).

Tell us about the Irish-American storytelling culture in which you grew up.

My parents came from Ireland and moved to a section of Boston where they were surrounded by their siblings and in-laws. We grew up with all our uncles and aunts nearby. They gathered every Friday and Saturday at one or another’s house. They would sit around and just tell stories. My brother and I began noticing every six or seven weeks, the same story would come back into the rotation. But, it was tweaked. We began to understand—whether consciously or not—a good story wasn’t necessarily concerned with facts. It was concerned with a basic truth. As an adult, I realize what my parents, uncles and aunts were doing by telling these stories again and again—all about the old country. They were trying to make sense of the diaspora; to make sense of having left the place they loved.

Do you think they romanticized the old country?

Oh, of course. When I went to Ireland, I expected to step back into the 1930s. You know, nobody got divorced; no one ever said a cuss word; and everything was just perfect. That image was calcified in my home in Boston. But in Ireland, time had moved on. They were living their lives.

When I was in graduate school, my mentor would describe storytelling as ‘the lie that tells the truth.’

Many of your novels, including World Gone By, are filled with moral ambiguity. Tell us about that.

The vast majority of what we call morality is simply fear of being caught. Just look at any comment section in articles on the Internet, where people remain anonymous and say whatever they think. Or, watch people when they’re driving their cars. Maybe a small percentage of us with moral fiber will categorically not do certain things, even if we’re not being watched, but with the vast majority, all bets are off.

I don’t know too many really bad people; and I don’t know too many saints. I think most people fall in-between. And, that’s what I write about. Bad people don’t wake up each morning thinking ‘I’m a bad person.” They think, ‘I’m a good person in my heart, even if I have to do some bad things.’ That’s true of bankers, and it’s true of stockbrokers who short stock. And that’s true of gangsters, who short people (Laughter).

In 2001, Mystic River was your first novel outside the Kenzie-Gennaro series. It wasn’t until 2010, when you brought the duo back in Moonlight Mile. Did you get pressure from fans to return to that series?

I didn’t really get pressure; I got wishes. Fans continue to show up at nearly every signing and want to know if Patrick and Angela will ever come back. My answer is, ‘I don’t know.’ I haven’t retired them. They’ve sort of taken these longer and longer vacations from me.

It seems to me you’ve taken a more expansive path in the last few years. Is that a fair statement?

Yes. I would say that path began after Mystic River. For the first time in my life, I became aware of other people’s expectation about what I would do next. I didn’t respond well to that pressure. It wasn’t why I got into writing in the first place. So, I made a conscious choice to zig when everyone thought I would zag. That’s when I wrote Shutter Island. Writing that book was really fun. I was able to do what I’d wanted to do for a very long time, which was to write about the Boston police strike. I’ve stayed on that independent path, despite knowing I’ve lost some fans along the way, but that’s okay.

So, Mystic River changed your writing life?

Yes. It changed the perception of me as a writer—almost overnight. Suddenly, I was viewed as a literary writer. Until that point, people thought, ‘He produces really well-written genre novels.’ That was my label. So, after Mystic River, I was suddenly writing literature. A lot of debates began after that. It was a strange and wonderful place to be.

So, you’re right, it led me to decide to follow a more idiosyncratic path.

I saw the film Mystic River and then read the novel. As fine as the film was, the book was even more powerful. Did the film have an impact on your writing life?

No. I don’t ever, ever, ever think of films when I write. To me, writing a book is a very intimate conversation I’m having with an imagined reader. It’s not a film script. A film script is just a blueprint—like an architectural diagram.

You once said, ‘Character is action. It’s the oldest law of writing. It goes back to Aristotle. Plot is just a vehicle in which your characters act.’ Will you amplify that?

I think a book is a journey by which a main character, or several characters, ultimately reach a reckoning with themselves. The plot is just the car driving them down the road on that journey. I don’t need a spectacular car. I just need one that’s serviceable. I’m not a car guy. With the exception of Shutter Island, I never wrote an original plot. All I do is make the plot serviceable, like the car. I work really hard on a plot, because you need to work hardest at the things that don’t come naturally. I don’t work hard at dialogue. It just flows. I barely rewrite it. Plot takes up the majority of my worry when I write a book because it’s the last thing I consider.

What has surprised you about the writing life?

That it’s as cool as I hoped it would be. (Laughter). You know, one of my favorite movies is Broadcast News. One scene describes my own life. There’s an interchange where William Hurt says to Albert Brooks, ‘What do you do when your reality exceeds your dreams?’ Albert Brooks say, ‘Keep it to yourself.’

That’s where I find myself. I go on book tours; I’m interviewed by people; and it gets put in newspapers. Even twenty years down the line, it still seems surreal to me. Surreal in a wonderful way. You know, last night at a book signing, someone asked me if I’d sign a paperback. I said, ‘Of course.’ And he said, ‘Some authors don’t sign them.’ I said, ‘What the hell did they get into writing for?’ I mean, there was a time when you were a complete nobody, and in your fantasy life you thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool if somebody actually wanted me to sign one of my books?’ I still live in that place—where it all seems like a fantasy.

The thing is: I get paid to make shit up. I’d be doing it for free. I walk around thinking, ‘These lunatics actually pay me to do this.’ If a planeload of money was dumped on me, I’d continue doing what I do.

I was going to ask what you love about the writing life, but you’ve already answered that.

They pay me to make shit up and I can keep my own hours. (Laughter).

If you weren’t writing, what would you be doing?

Everybody has some fantasy about this kind of thing. I’m thinking I would be a carpenter. There’s no reason for me to think that since I’ve never shown I can do anything with my hands. But I feel that’s what I’d like to do if I wasn’t writing.

You would certainly see the results of your labor.

Yes. I need to see the results of anything I do, whether it’s a book or a cabinet.

If you could have five people to a dinner party, from any walk of life, living or dead, who would they be?

First, I’d have Gabriel Garcia Marquez. I’d also invite FDR and Bill Murray. And then…Keith Richards. I would also like to have dinner with Joan of Arc.

What would you be talking about?

With that group? What a party it would be. There would be no problem with conversation.

Congratulations on writing World Gone By, described by Kirkus as “a multilayered, morally ambiguous novel of family, blood and betrayal.” And I agree completely with that assessment.

March 19, 2015

‘World Gone By’ A Conversation with Dennis Lehane

Dennis Lehane is known to millions of readers. His novels Mystic River, Gone, Baby,  Gone, and Shutter Island became blockbuster movies, with the most recent film being The Drop, which is based on his short story, Animal Rescue.

Gone, and Shutter Island became blockbuster movies, with the most recent film being The Drop, which is based on his short story, Animal Rescue.

A Drink Before the War won the Shamus Award. Mystic River won both the Anthony and the Barry Awards for Best Novel, and the Massachusetts Award in Fiction. Live by Night won the Edgar Award for Best Novel, and the Florida Book Award Gold Medal for Fiction.

World Gone B...

March 18, 2015

‘The Stolen Ones’ A Conversation with Owen Laukkanen

Owen Laukkanen’s debut novel, The Professionals, received high praise and was nominate d for many honors, including the International Thriller Writers’ Award, the Anthony, the Barry, and the New Voices Awards. He graduated from the University of British Columbia’s creative writing program, and before turning to fiction, spent three years reporting on the world of professional poker.

d for many honors, including the International Thriller Writers’ Award, the Anthony, the Barry, and the New Voices Awards. He graduated from the University of British Columbia’s creative writing program, and before turning to fiction, spent three years reporting on the world of professional poker.

The Stolen Ones is the fourth novel in the series featuring Kirk Stevens and Carla Windermere, partners in the M...

March 15, 2015

‘Phantom Limb': A Conversation with Dennis Palumbo

Dennis Palumbo is a thriller writer and psychotherapist in private practice. He’s the author of the non-fiction book, Writing from the Inside Out and a collection of mystery stories, From Crime to Crime. He has also been writing the Daniel Rinaldi mystery series. He was formerly a Hollywood screenwriter, whose credits include the film My Favorite Year, which was nominated for a Writers Guild of America Award for Best Screenplay. He was a staff writer for the TV series Welcome Back, Kotter. Cu...

March 9, 2015

“Endangered”: A Conversation with C.J. Box

J. Box is the bestselling author of 16 Joe Pickett novels, four standalone novels, and a col lection of short stories called Shots Fired. He’s won multiple awards including the Edgar, the Anthony, the Gumshoe, and the Barry awards. He lives with his family outside Cheyenne, Wyoming.

lection of short stories called Shots Fired. He’s won multiple awards including the Edgar, the Anthony, the Gumshoe, and the Barry awards. He lives with his family outside Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Endangered begins with Wyoming game warden Joe Pickett learning his 18-year old adopted daughter, April, has disappeared. She’s found in a ditch along a highway. April, the victim of blunt force trauma, is in a coma...

March 5, 2015

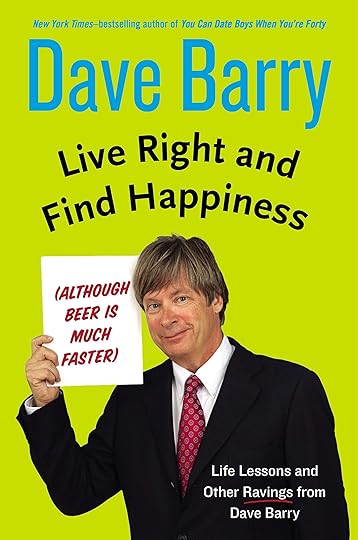

“Live Right and Find Happiness” A Talk with Dave Barry

Dave Barry is a Pulitzer Prize-winning humorist and New York Times bestselling auth or of Insane City and You Can Date Boys When You’re Forty. From 1983 to 2005, he wrote a nationally syndicated humor column for The Miami Herald.

or of Insane City and You Can Date Boys When You’re Forty. From 1983 to 2005, he wrote a nationally syndicated humor column for The Miami Herald.

In Live Right and Find Happiness (Although Beer is Much Faster), Dave articulates certain life truths to his new grandson and to his daughter Sophie, who will be getting her learner’s permit this year (“So you’re about to start driving! How exciting! I’m going to kill...