David Boyle's Blog, page 56

March 20, 2014

Why 2014 was a historic budget (it isn't what you think)

In my rapidly receding youth, Budget Day was a bit like the Grand National or the FA Cup Final. You half expected the Chancellor to be led from his paddock while Jimmy Savile was being dragged out to lead everyone singing 'Abide With Me'.

In my rapidly receding youth, Budget Day was a bit like the Grand National or the FA Cup Final. You half expected the Chancellor to be led from his paddock while Jimmy Savile was being dragged out to lead everyone singing 'Abide With Me'.These days, most of the budget is leaked in advance and doesn't amount to more than a few tweaks here and there, and then there is the Autumn Statement and the Mansion House Speech and all the rest.

The Budget is important, but somehow not the spectator sport it once was. I remember people crowding round the windows of the TV shops to watch. We have Blackberrys and iPads these days, but I'm not sure we are glued to them for the Budget as we used to be.

Part of this is that, actually, it isn't very disputed. Despite the sound and fury from Balls and his colleagues, Labour is not committed to doing much different. There is no great divide in Westminster these days. The divide is between Westminster and the rest (exemplified in the strange Conservative bingo poster yesterday).

But actually I think the 2014 Budget will be recognised as a key turning point. George Osborne may have chosen the words "makers, doers and savers" because they sound conservative in the best sense (and they do) - but the very idea that budgets are supposed to support makers and doers is mildly revolutionary.

This particular budget may not actually have helped them that much. That's not the point I'm making. The point is that it has been accepted wisdom since Geoffrey Howe's first budget in 1980 that budgets are supposed to support speculators, wealth-creators and lenders. That was the logic of trickle down.

Osborne's support for makers and doers is an explicit new direction for conservatism, away from the idea that financial services was the key to the economy, the great mistake at the heart of the Lawson and Brown years.

In fact, I am comforting myself that Osborne has in fact been reading my book Broke: How to Survive the Middle Class Crisis, where you will find a pre-emptive defence of the budget. Especially its support, against the imprisonment of the middle classes by the big insurance companies, for the changes to annuity regulations (Steve Webb's important contribution).

It is still the beginning. There is still so much, nearly everything, to do to make the economy effective, balanced and humane. But in the great 30-year stand-off between the forces of Trickle Up and the forces of humanity, the other guy just blinked.

The other element of the budget to help people with families, the £2,000 for childcare, I'm not so excited about.

The money is just as likely to push up the cost of childcare and the Budget fails to do what is urgently needed - a major roll-out of self-financing co-operative nurseries, on the North American and Scandinavian model. That has the potential to halve the cost of childcare, so why are we not doing it? (more on this later).

As I say, there is still nearly everything to be done. But the rhetorical support for makers and doers, after three decades of support for those who toil not and neither do they spin (but they do speculate) is absolutely critical and potentially historic.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word subscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 20, 2014 02:20

March 19, 2014

Could austerity save public services?

In those heady days immediately after the 2010 general election, I used to argue that 'austerity' might play an urgent and vital role in rescuing public services.

In those heady days immediately after the 2010 general election, I used to argue that 'austerity' might play an urgent and vital role in rescuing public services.I doubt whether anyone paid much attention. They looked at me as they often did, as if they found it hard to place me exactly. But I argued this on the Lib Dem federal policy committee, so - who knows - it could have strengthened the ambition for austerity in small ways.

I thought that austerity might be the only way to shock services, which had been hollowed out by New Labour's targets regime and a decade or so of wrong-headed care by McKinsey and PA Consulting, into being humane and effective again.

I believed it may be the only way to force them to re-organise in innovative ways to meet people's needs. At the time, I also believed that iron central control was costing at least £48 billion just in accountability and auditing.

There have been many times since then that I have wondered whether I was right after all. I watched the best innovative ideas being cut and the most intractable, sclerotic companies taking over services by pushing the costs elsewhere in the public sector.

Yet there were also signs of hope. In the north west, particularly, there was the iNetwork of local authorities dedicated to thinking afresh. There was co-production popping up everywhere and Nesta's People-Powered Health project.

Now, for the first time, it seems to me, there is a genuine challenge emerging to the old way of doing things, and it is published this week in a Locality report called Saving Money by Doing the Right Thing - and it merges John Seddon's system thinking approach with what I would call co-production (but they call 'helping people to help themselves').

There are ambitious claims being made for th

is approach. The report claims that £16 billion can be saved delivering services on this model.

An even more ambitious way of looking at it is set out in the blog Freedom from Command and Control, which tries to turn the famous Graph of Doom on its head - explaining that, if you take Seddon's 'failure demand' into account (the excess demand on services caused by doing them badly in the first place), then the Graph of Doom goes backwards.

This is a big claim, but it is no less than what Beveridge originally claimed for his Welfare State - that it would get cheaper over time.

The question of why that hasn't happened is one of the most important unasked condundrums about public services now.

I'm not saying that austerity is right in every circumstance. Just because a little austerity kickstarts innovation, it certainly doesn't mean that the same would apply to a lot of austerity. Moderation in all things, and especially when it comes to austerity.

But our inflexible sclerotic services needed an injection of life, and the debate about how to achieve that is now joined. This blog post is my modest attempt to help it along.

More on these issues in my book The Human Element.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word subscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 19, 2014 02:18

March 18, 2014

Lego and the unlamented end of evidence-based policy

Like many people of my age, I must be an absolute expert in all things Lego. I have played with it, tidied it away, trodden on it in the middle of the night, and am doing so all over again with my own children.

Like many people of my age, I must be an absolute expert in all things Lego. I have played with it, tidied it away, trodden on it in the middle of the night, and am doing so all over again with my own children.There is a sense also that Lego is almost the last game standing. Go to the great empty echoing chamber of Toys R Us (my youngest believes it is called Toys Are Rust, and there is some truth in this), and you will see the swathes of Lego driving out the rest.

The rest is nearly all TV or movie tie-in stuff, with a very short half-life, destined for the skip. There are some plastic kits for older children, there is sports gear and there is Lego.

It is worth asking why. The answer, I think, is that - unlike all the expensive TV tie-in tat - Lego releases the imagination. The rest tries to constrain it.

But the reason I have been thinking about Lego is because there is a fascinating article in the latest Fortune magazine about how the Danish company managed to claw itself back from the brink a decade ago, when it was losing about £1m a day.

There are various versions of this in circulation. One is the precise opposite of what I'm saying here, I have to admit: it was the adoption of Star Wars tie-in Lego, with weapons - flying in the face of the company's pacifist tradition.

But here is another one, and I was interested because it seemed to me to me a little more evidence that the data glacier is finally melting, the old nonsense about evidence-based policy (actually nothing of the sort) is slowly beginning to crumble.

It describes how Lego tried focus groups to help them out of their hole, only to find that the children were just telling them what they thought they wanted to be told. They then took on a Danish consultancy called ReD, which helped them observe how children play in their own homes.

There was a lightbulb moment when they asked an 11-year-old German boy to show them his favourite toy and he came out with a battered old sneaker, where every mark showed where he had mastered a new trick on the skateboard.

It led to an important insight: children had not changed. They didn't necessarily want toys that were glitzy, shiny, hi-tech and new. They wanted to be able to experiment on their own. This is the strategy that Lego has pursued since - punters certainly relish the movie tie-ins, but they can take them apart, remould them, add in their ow stuff, mix Harry Potter and the Hobbit if they want.

But this isn't one of my homilies about authenticity. You can read one of those here if you want. It is about the collapse of the idea that you can measure your way to business and political solutions.

Of course the data helps, but it isn't enough. This is how Fortune put it:

"It was a rebuke of sorts to the traditional business consulting firms - and to the very notion that a company can understand its customers simply by crunching numbers."

Quite right, and ironically ReD's chairman Bill Hoover is a former senior director of the source of this wrong-headedness, the consultants McKinsey, authors of the famous McKinsey Fallacy ('everything can be measured and what can be measured can be managed').

If only Whitehall could grasp the idea that the data isn't enough, but they are now drowning in graphs - paralysed because they don't realise they some imagination and intuition is also required. The world and the people who live on it are much too complicated for policy to be a humming logical machine that can just manage the world by itself.

If you want to know what happens when you try that - the fearful legacy of New Labour - just look around you.

Find out more in my book The Tyranny of Numbers.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word subscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 18, 2014 03:17

March 17, 2014

Back to the Edwardians

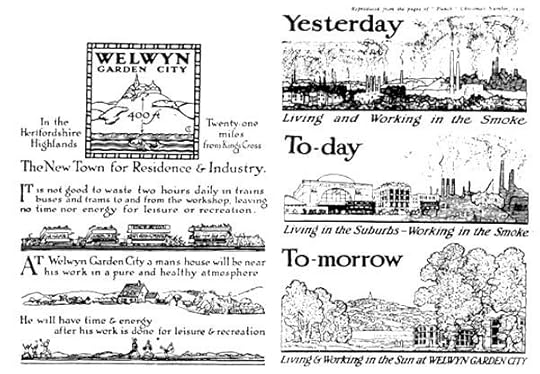

In a number of disturbing ways, the news has been worryingly reminiscent of a century ago. If it isn't the tussles over the meaning of free trade inside the Conservative Party in the UK - the Euro-sceptic debate is an echo of the painful divisions over 'imperial preference' - it is the clash between rival networks of alliances in Crimea and Serbia.

In a number of disturbing ways, the news has been worryingly reminiscent of a century ago. If it isn't the tussles over the meaning of free trade inside the Conservative Party in the UK - the Euro-sceptic debate is an echo of the painful divisions over 'imperial preference' - it is the clash between rival networks of alliances in Crimea and Serbia.Now there are also garden cities. There is a grumbling disagreement between the coalition partners about the thoroughly Edwardian idea of 'garden cities'. Lib Dem president Tim Farron just criticised the Conservatives for suppressing a report recommending two of them. Now there has been a new garden city announced for Ebbsfleet.

What really exercised the minds of our Edwardian forebears was the argument between garden cities and garden suburbs. Lo and behold, I found myself arguing exactly that debate again at the party conference in York.

I've often wondered whether I was an Edwardian born out of time (48 years too late, in fact). It begins to look as if I was born at the right time after all.

George Osborne announced that the new garden city will be organised by an urban development corporation. This was the idea, modelled on the BBC, that was conjured out of the Attlee government to build new towns in 1946. It makes sense, but there is something missing nonetheless.

Ebenezer Howard's original scheme for Letchworth Garden City was for the people who lived there to have an ownership stake in the land, and to use the rise in land values to pay for the quality of life in the new garden city - as it still does, just about, in Letchworth.

This is now, once again, as important a consideration as it was a century ago. Unless some mechanism is put in place, then the development corporation will use the rise in land values to pay for the infrastructure, but will then wind itself up - or sell itself off - and leave everything as it was before.

If it is a success, Ebbsfleet will then be owned in the normal way by landowners and developers, with no stake for the people who live there - whose children will be priced out by the ridiculous property value inflation that we allow in this country by failing to control the amount of money pouring into the housing market.

Will George Osborne have thought through any of this before making the announcement? Almost certainly not, which is a pity given that it isn't exactly new thinking. There is nothing new about the idea of separating the ownership of the land and the ownership of the buildings on it.

But if you want to see how these things might be done, you need look no further than the emerging community land trust movement in the UK.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word subscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 17, 2014 04:08

March 14, 2014

Don't you know there's a war on?

It's a funny thing, but travelling by rail is a much easier experience in the UK these days. It is one of those areas of public life that have improved dramatically - especially on the London underground. I belong in the generation when we would stand for hours, peering hopelessly up a tunnel, waiting for the old newspapers to swirl around to show there was a train on the way.

I even went on Virgin Trains to Lancashire on Monday and was bang on time, there and back. There are other reasons I don't enjoy Virgin Trains - the peculiar smell of urine in their coaches for example, and the way their staff seem disempowered and disinclined to help when things go wrong - but I'd never associated them with punctuality before.

The only place, in my direct experience, where this improvement has failed to take place is on Southern, which operates my regular commute from Norbury to Victoria.

Trains regularly disappear and I haven't caught one that was on time for weeks, since before the storms. What is most irritating is that, if you catch the 0926 you have to pay £3 more than if you catch one after 0930 - but the 0926 it hasn't arrived before 0930 for weeks.

I had a fascinating conversation recently (thanks, Paul) about the effect of the storms and floods on the rail services. Broadly, there seem to be two possible impacts on staff:

1. They are motivated to make huge efforts, beyond the call of duty, to get their passengers home.

2. The opposite happens, because the storms provide them with an excuse for poor service.

This latter effect can be summed up in the old 1940s excuse for not trying very hard: "Don't you know there's a war on?".

I've no idea if this is the reason why Southern seems unable to operate to their own timetable, but it occurs to me that the "Don't you know there's a storm on?" attitude can be a direct result of a corporate culture too dependent on targets.

We know from research into volunteering and behavioural economics that, if you offer to reward people for things they were doing before for altruistic or idealistic reasons then, after a while, the altruism disappears.

It is the same with targets. If you treat your staff like automatons, and are continually using carrots and sticks, then in the end that takes over the corporate culture. When you treat people like amoral automatons, that is what they become.

In those circumstances, storms and floods become - not so much a challenge to overcome - but an excuse not to meet targets. It is another way that McKinsey-style corporate culture has hollowed out our institutions.

Whether that explains yet another delay this morning, I have no idea. But they do have an excuse: there was a storm last month.

I even went on Virgin Trains to Lancashire on Monday and was bang on time, there and back. There are other reasons I don't enjoy Virgin Trains - the peculiar smell of urine in their coaches for example, and the way their staff seem disempowered and disinclined to help when things go wrong - but I'd never associated them with punctuality before.

The only place, in my direct experience, where this improvement has failed to take place is on Southern, which operates my regular commute from Norbury to Victoria.

Trains regularly disappear and I haven't caught one that was on time for weeks, since before the storms. What is most irritating is that, if you catch the 0926 you have to pay £3 more than if you catch one after 0930 - but the 0926 it hasn't arrived before 0930 for weeks.

I had a fascinating conversation recently (thanks, Paul) about the effect of the storms and floods on the rail services. Broadly, there seem to be two possible impacts on staff:

1. They are motivated to make huge efforts, beyond the call of duty, to get their passengers home.

2. The opposite happens, because the storms provide them with an excuse for poor service.

This latter effect can be summed up in the old 1940s excuse for not trying very hard: "Don't you know there's a war on?".

I've no idea if this is the reason why Southern seems unable to operate to their own timetable, but it occurs to me that the "Don't you know there's a storm on?" attitude can be a direct result of a corporate culture too dependent on targets.

We know from research into volunteering and behavioural economics that, if you offer to reward people for things they were doing before for altruistic or idealistic reasons then, after a while, the altruism disappears.

It is the same with targets. If you treat your staff like automatons, and are continually using carrots and sticks, then in the end that takes over the corporate culture. When you treat people like amoral automatons, that is what they become.

In those circumstances, storms and floods become - not so much a challenge to overcome - but an excuse not to meet targets. It is another way that McKinsey-style corporate culture has hollowed out our institutions.

Whether that explains yet another delay this morning, I have no idea. But they do have an excuse: there was a storm last month.

Published on March 14, 2014 03:50

March 13, 2014

The peculiar bias against 'knowledge'

I found myself delving deeper into Croydon’s peculiar library service yesterday, and I have to say I'm even more confused than I was before.

I found myself delving deeper into Croydon’s peculiar library service yesterday, and I have to say I'm even more confused than I was before.The service is flexible and human and able to order me books from anywhere and send them anywhere. Their people in libraries are brilliant and helpful. But there remains a mystery.

I was reminded of it when I was searching for a copy of Gulliver's Travels in Croydon's central Library. There wasn't one in any of the branch libraries (except one) and I had to order a battered old copy of Swift's collected works from the reserve, a dusty room evidently a long way away.

Swift has long since made way for the latest autobiography by Cheryl Cole's ghostwriter.

I ventured into Thornton Heath Library, recently revamped so that it won an architectural award. I ventured into Norbury Library only last week and the mystery is the same: where on earth are all the books?

Last time I blogged about this, I discovered that there was a whole website dedicated to solving the mystery: what has Croydon done with the books, let alone the shelves (I can't find it now)?

But, more recently, I have realised that this is actually a symptom of a deeper problem. You might call it the Flight from Facts, or perhaps an extreme scepticism about content and knowledge.

Most educationalists agree these days that the point is not to fill children’s minds with facts, but to light a fire to encourage learning. It is not to mould them into encyclopaedias but to give them the tools to find out what they need.

But you don't really have to throw out these truisms to be a little worried about where it is taking us. Because it can and does go too far – especially when the internet gurus, and corporate interests behind them, get hold of the idea and boil it down to the point of dangerous incoherence.

Why, they say, do children need to know anything very much, apart from how to use a search engine? Why not just obsess about the pathways in our brains where we connect knowledge, and forget about the knowledge itself?

It is all a bit like encouraging children to be healthy by obsessing about their intestines, but never feeding them. The two actually belong together, and if you stop giving people food their intestines shrivel up.

The result has been an undebated bias among librarians and educationalists against the basic knowledge that our children might once have learned, about history, geography, science and much else. The result is empty shelves in the libraries, while people who can't afford their own screens stare hopelessly at YouTube - and hardly anyone you meet seems to know anything much.

I'm not saying the ideology is wrong. I met a Polish historian recently who was shocked that her UK lecturers knew so few dates – Polish historians can still reel them all off. Maybe we don't need to obsess about dates.

But there is a deeper problem here, because you can't draw an absolute line between the means to get knowledge and the knowledge itself, between knowing how and knowing what. Without any knowledge, people lose the ability to tell sense from nonsense. They fall prey to any kind of rubbish.

As Chesterton once said about Christianity. When people stop believing in orthodox religion, they don't believe nothing; they start believing in anything. The same kind of thing is true of knowledge: if people don't have any, they are not free-thinkers - they become no-thinkers.

Michael Gove isn't right about everything, God knows, but he is right about this. And I'm afraid those empty bookshelves in our libraries is becoming a metaphor for our empty minds.

Published on March 13, 2014 04:05

March 12, 2014

Now I know the age of 'prevention' has begun

Harry Hopkins, the close adviser to Franklin Roosevelt as president, ran some of the key agencies of the New Deal, including the Works Progress Administration. Roosevelt asked him to run it because of the urgent need for unemployment relief during the winter, then just weeks away, and because he was capable of getting money and jobs where it was needed within a matter of weeks.

Harry Hopkins, the close adviser to Franklin Roosevelt as president, ran some of the key agencies of the New Deal, including the Works Progress Administration. Roosevelt asked him to run it because of the urgent need for unemployment relief during the winter, then just weeks away, and because he was capable of getting money and jobs where it was needed within a matter of weeks.In fact, as head of the new Civil Works Administration, Hopkins summoned the mayors and governors to see him in Washington on November 15 1933, and asked them for immediate proposals for work projects. By November 26, nearly 50,000 were in new jobs - and that was just in Indiana.

By Christmas, he was employing 2.6 million impoverished Americans.

These days, when there are still outstanding claims for compensation for damage in the 2011 riots in the UK, we are in need of a British version of Hopkins - by skill, guile and force of personality, able to make things happen.

In my rare glimpses of the coalition in action, it seems to me that the frustration that administration moves so staggeringly slow, and so many hurdles are thrown in the path of almost any measure - whether it is imaginative or hopeless- is shared by Lib Dem and Conservative ministers alike.

It is difficult, and partly - as I've written elsewhere - because of the extreme complexity of modern bureaucracies.

So I was excited by David Laws highly effective and convincing defence on The World at One of the new free school meals policy, which is - like all imaginative policies - difficult to implement. I was excited partly because he was so confident and partly because, of all the Lib Dem achievements in government, this one thrills me the most.

I mean, how many times do we get a bold and enlightened policy like that through the Whitehall maze? And now even the Daily Mail has taken umbrage over some bizarre story that one primary school is going to take three hours to serve the meals.

Of course, it isn't going to be easy. The policy was brought in for three primary school years, in only twelve months, when every effort has been made to close down school kitchens under previous governments, and to truck in meals for two hundred miles or so for re-heating at some depot.

What makes this policy so enlightened is that it marks the start of a new way forward. A measure that is designed simultaneously to feed children healthy food, help them learn, socialise them and save their parents money, all at the same time.

The age of prevention has clearly begun, and this kind of policy with multiple, overlapping objectives is a feature of the new age.

Of course there will be difficulties in some places. Headteachers and local education officials will have to be imaginative and innovative, and should be praised for being so.

Of course it will also cost money, and these kind of projects have a habit of bursting their budgets. But although education budgets have been suffering, along with all the others, the pupil premium has boosted the coffers of some of the poorer schools. So much so that the CEO of Apple pointed to the mass purchase of iPads by UK schools was a major factor in their profits last year.

This may be old-fashioned of me, but I believe that sitting down to a healthy, hot meal once a day will benefit children a good deal more than a whole truckload dose of iPads.

It isn't just a blow for health and learning. It is a blow for authenticity too.

Published on March 12, 2014 09:33

March 11, 2014

Crimea and its terrifying echoes of Munich

My great-aunt was Observer correspondent in Prague in 1938. It was said that she wept the whole way home by train after the Munich agreement, as she returned to launch a rather belated Penguin Special called Europe and the Czechs. By then, Britain and France had agreed to Nazi annexation of the Sudetenland.

My great-aunt was Observer correspondent in Prague in 1938. It was said that she wept the whole way home by train after the Munich agreement, as she returned to launch a rather belated Penguin Special called Europe and the Czechs. By then, Britain and France had agreed to Nazi annexation of the Sudetenland.I keep thinking of her as the depressing and frightening news from the Ukraine pours in, especially now it seems clear that the Russians seem intent on annexing the Crimea.

It is depressing because of the growing parallels between the two events, just 75 years apart.

The point about Munich was that it was a failure. It was intended to end Nazi expansion and it only fed the beast, but that only became apparent six months later when they annexed the whole country. Before that, there was a context of self-determination by the Sudeten Germans which made it seem as if there was a case to answer.

The key question before Chamberlain and Daladier was not whether it was right or wrong to let what seemed to be the majority have its will in the Sudetenland - but: would this be the limit of Nazi territorial ambitions?

That is the great fear about Crimea. There is clearly a slither of a case for self-determination. But would taking over the Crimea satisfy Putin, or would it just encourage him to look hungrily at Estonia, Latvia or Georgia?

That is why NATO is now patrolling the airspace in Poland and Romania. It is why this situation is so dangerous.

It is also why people like Owen Jones, who believe that it would be hypocritical for the West to complain about Russian incursions, are wrong. It is the most dangerous stand-off since the Russian invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 or the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.

We all know that European wars begin in Poland. It is possible to imagine how Poland could be the source of another one.

But Owen Jones is right that self-determination is too simple a yardstick. He is also right that we cling to it when it suits us, as it does in the Falklands or the Balkans. Yet we also promote it when it doesn't suit us. Scotland springs to mind. Self-determination is important, but it is more than just winning elections - as any observer of Northern Ireland can see over the past generation.

This is why I remember my great-aunt, Shiela Grant Duff, whose book about the period describes vividly the fake self-determination of the Saar Plebiscite, and the terrible consequences after the vote for those who had opposed unification with Germany.

The question is this: will the Crimea vote be another Saar Plebiscite, with its terrible aftermath? It begins to look like it will.

Published on March 11, 2014 04:24

March 10, 2014

The real evil is power without purpose

I am old enough to have worked in the Liberal assembly press office back in 1986, the year of the ‘ten-fingers-on-the nuclear button’ furore which tore apart the Liberal-SDP Alliance.

I am old enough to have worked in the Liberal assembly press office back in 1986, the year of the ‘ten-fingers-on-the nuclear button’ furore which tore apart the Liberal-SDP Alliance.I remember the raging arguments in the corridor after David Steel’s furious speech, tearing into his own party:

“I’m not interested in power without principles, but I am only marginally interested in principles without power.”

It will certainly be in Duncan Brack’s excellent new Dictionary of Liberal Quotations.

Looking back, now the party has power of a kind, this opposition of power and principles seems to reek of the peculiar culture of Liberals. I’m not even sure it is the right question.

The real problem in Westminster is that it is packed to the gunwhales with highly skilled professional politicians, who are adept at the techniques of gathering power to themselves. They imbibe it in their mother’s milk, have it in their tea at Eton, learn it in the corridors of power as research assistants and special advisors and finally they do it themselves.

The problem isn’t that they are power-crazed tyrants; it is altogether different. They get the power only to find that they haven’t got the foggiest idea what to do with it.

For the sake of argument, let’s call it the Blair Paradox. You might also call it the Brown Paradox, because the two great rivals shared it.

They tweaked the system so much that they were able to gather the reins of the nation’s horse in their hands.

But by then, they had become so much a part of the complex system of government that they found it next to impossible to imagine anything much outside the status quo.

This is important for the Lib Dems because they have survived the trauma of coalition – and it has been an exciting roller-coaster but deeply traumatic at times – by suffusing themselves in the science of political pragmatism.

The sheer intractability of the system drove them to become experts in the details of making things happen in Whitehall. I am impressed by it but nervous about it too.

The bitterest battle at the Lib Dem conference in York was over regionalism, which seems an appropriately Liberal cause to get cross about.

It wasn’t between the people with principles and the people with power, it was between those who wanted to think through the philosophy from first principles, and those who wanted to put up with an untidy solution because that was the only way anything would happen.

Now, it happens that I believe in untidy solutions. They are consistent with localism and with human beings.

But I felt I detected the revival of the logical thinkers at the conference, re-thinking the way the world is.

Was it that, or was it just the last throw of the old defunct causes which we clung to during the 1970s and 1980s? I don’t know.

But it is important. Liberalism will survive in the long-term by nurturing both kinds of knowledge – the purity of imagination, to see the world differently, but also the hard-headed business of making it happen.

When St Augustine urged us to be as wise as serpents and as harmless as doves, I have a feeling he was talking directly to the Lib Dems.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word subscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 10, 2014 03:25

March 7, 2014

Four decades on: the besetting sin of Liberals

Exactly forty years ago, the strange final chapter was being played out for the February 1974 general election, which saw Edward Heath holding on in 10 Downing Street while he negotiated with Jeremy Thorpe.

Exactly forty years ago, the strange final chapter was being played out for the February 1974 general election, which saw Edward Heath holding on in 10 Downing Street while he negotiated with Jeremy Thorpe.I was preparing for O Levels at the time (a strange prehistoric version of GCSEs, for those who don't remember) and I remember finding myself in instinctive sympathy with the underdog - the Liberals had won six million votes but only 14 seats. It was a travesty.

Looking back, it was the first time I identified with the Liberal Party, though I didn't actually join for another five years.

It all seems rather a long time ago, over the horizon of history. So it has been strange reading about the events on the BBC website, and hearing - by sad coincidence - of the death of Marion Thorpe in the last few days.

I was a great admirer of Thorpe's in those days, and have since been lucky enough to meet him and Marion at their home a number of times.

I still think he was, and is, an extraordinary man, despite the events that followed. But looking back, I wonder if his leadership did not fall into the classic Liberal trap: high intelligence, a compelling presence, but another Liberal ecstacy of positioning rather than anything important to say.

It has been the besetting sin of the party I joined for most of the past century.

I joined in 1979, for two reasons. One was that I interviewed the Liberal candidate for Oxford for two whole hours at the height of the election campaign, as a student journalist. By the end of the conversation, I was completely convinced.

But there was another reason. The stance of the Liberal MPs the previous year, going into the no lobby alone against the reprocessing plant at Windscale, as we called Sellafield on those days.

At least half the reason I joined the party was that it realised, when none of the other Westminster parties did, that nuclear energy would be vastly wasteful and centralising.

Looking back, I couldn't have joined any other party. I am a Liberal, despite the recent app which allows you to rate your political position, which concluded - despite all evidence to the contrary - that I was a Scottish nationalist (this was not useful advice: it is some years since the SNP fielded candidates in Croydon).

But I've been mulling over my four decades rooting for the Liberals and Lib Dems, since the aftermath of the February 1974 election - almost my entire adult life. Like most of my friends in the party, we all spend at least as much time frustrated with the party as we do campaigning for it, but usually - being Liberals - for different reasons.

Looking back, I think I came to the conclusion some years ago that - if I was to play any useful role in the party - it would be to try and tackle this besetting sin: the preference for positioning over thought.

Which brings me back to the nuclear issue. I support the coalition, but no issue has made me more enraged with my own party's besetting sins than the vote in September to back nuclear energy, but without a state subsidy.

Nothing preys on my mind more than that. The embarrassing self-delusion involved. The stupid, thoughtless positioning.

As if an industry that produces high level waste without any storage facilities, except its current temporary one on the surface at Sellafield - and without any prospect of storage facilities (three Albert Halls of it so far) - which will stay dangerous for 100,000 years.... As if we can pretend that will involve no subsidy.

So for the sake of Lib Dem positioning, we hand the next 2,000 generations the task of protecting and paying for this stuff - for millennia after the disappearance of any of the companies we are subsidising.

I find it quite staggering that we could have made a decision so transparently delusory, just to help our Secretary of State get over a little political difficulty.

Yet, here I am, four decades after my O Levels, toddling off to the party's conference York. A strange thought.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word subscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 07, 2014 03:36

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.