Michael Gray's Blog, page 5

November 22, 2014

HOAGY AND BOB AND LUCY ANN POLK

On this, the 115th anniversary of Hoagy Carmichael's birth, here's his entry in The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia:

Carmichael, Hoagy [1899 - 1981]Hoagy Carmichael was born Hoagland Howard Carmichael on November 22, 1899 and raised in Bloomington Indiana. He grew up to be a singer and actor but primarily a popular songwriter. His very first composition was called ‘Freewheeling’, and he also wrote a song titled ‘Things Have Changed’. More famously he wrote or co-wrote, among many, many others, ‘Stardust’ and ‘Georgia On My Mind’. Carmichael is one of the many improbable people whose work and persona Dylan admires, possibly just to be perverse. Hoagy’s photo is pinned up on the wall of the shack behind him on the photo by DANIEL KRAMER planned for the US hardback of Dylan’s Tarantula but rejected (it’s reproduced in Kramer’s book Bob Dylan) and in the Empire Burlesque song ‘Tight Connection To My Heart’ Dylan names a Hoagy Carmichael composition. Dylan sings: ‘Well, they’re not showing any lights tonight / And there’s no moon. / There’s just a hot-blooded singer / Singing “Memphis in June”’. ‘Memphis In June’ was composed by Carmichael with lyrics by Johnny Mercer (who also wrote the lyric to ‘Moon River’, which Dylan sang one night on the Never-Ending Tour in tribute to the late STEVIE RAY VAUGHN). Dylan’s ‘hot-blooded singer’ is a neat small joke about Hoagy, whose many assets include a calculatedly lizard-like presence. It was a joke Dylan had retained from an earlier version of the song, then called ‘Someone’s Got A Hold Of My Heart’, which he’d recorded at the sessions for Infidels, the album before Empire Burlesque. At least two performances of this have floated around, but the one eventually released officially, on The Bootleg Series Vols. 1-3 in 1991, offered these alternative lines: ‘I hear the hot-blooded singer / On the bandstand croon / “September Song”, “Memphis in June”’. Clearly Dylan was determined to retain Hoagy, whatever other changes he made. (‘September Song’ was written by Maxwell Anderson and composed by Kurt Weill for the 1938 Broadway play Knickerbocker Holiday.) ‘Memphis’ was written for the 1945 George Raft film Johnny Angel, in which Carmichael played a philosophical singing cab driver. (‘After that I was mentioned for every picture in which a world-weary character in bad repair sat around and sang or leaned on a piano’). Subsequent film roles included being the pianist who sings ‘Hong Kong Blues’ in the Bogart-Bacall film To Have And Have Not, one of Dylan’s favourite hunting-grounds for lyrics in the Empire Burlesque period. The least hot-blooded cover version of ‘Memphis In June’ may be by Matt Monro, from 1962; the best (and ‘on a bandstand croonin’’) may be by Lucy Ann Polk, cut in July 1957 in Hollywood. Hoagy himself recorded the song in 1947 with Billy May & His Orchestra and again in 1956 with a jazz ensemble that included Art Pepper. Carmichael and Mercer also wrote that great song ‘Lazy Bones’ - in twenty minutes, in 1933 - which was revisited magnificently in the 1960s by soul singer James Ray (who made the original US hits of ‘If You Gotta Make A Fool Of Somebody’ and ‘Itty Bitty Pieces’; in the UK he was unlucky enough to find these savaged in unusually distressing ways, even by the standards of British cover versions of the time, by Freddie & The Dreamers and Brian Poole in the first case and by The Rockin’ Berries and Chris Farlowe in the second). Carmichael played ranch-hand Jonesey in the 1959-60 season of the TV series Laramie. In 1972 he was given an Honorary Doctorate by Indiana University back in Bloomington (which is where BETSY BOWDEN got her doctorate for a study of Bob Dylan’s performance art that became her book Performed Literature). Hoagy Carmichael died two days after Christmas, 1981. When a retrospective 4-LP box set of his work, The Classic Hoagy Carmichael, was issued in 1988, with copious notes by John Edward Hasse, Curator of American Music at the Smithsonian Institution, it was released and published jointly by the Smithsonian and the Indiana Historical Society. (American hobbyists are so lucky: there’s always plenty of places to go for funding. Imagine trying to get funds to research, compile and write an accompanying book about Billy Fury from the British Museum and the Birkenhead Historical Society.) The Carmichael box-set notes say this, among much else, and might just remind you of someone else (not Billy Fury): ‘At first listeners may be distracted by the flatness in much of Carmichael’s singing, and turned off especially by his uncertain intonation. The singer himself said, “my native wood-note and often off-key voice is what I call ‘Flatsy through the nose’”. But... one becomes accustomed to these traits and grows to appreciate and admire other qualities of his vocal performances, specifically his phrasing... intimacy, inventiveness and sometimes even sheer audacity. Also, many... evidence spontaneous and extemporaneous qualities, two important ingredients in jazz.’_________

So here's 'Memphis In June' by Hoagy:

And by Lucy Ann Polk:

[Hoagy Carmichael: The Classic Hoagy Carmichael, 4-LP set compiled & annotated by John Edward Hasse; issued as 4 LPs or 3 CDs, BBC BBC 4000 and BBC CD3007, UK, 1988; Johnny Angel, , dir. Edwin L. Marin, written Steve Fisher, RKO, US, 1945. Daniel Kramer: Bob Dylan, New York: Citadel Press edn, 1991, p.127. Betsy Bowden: Performed Literature, Bloomington: Indiana University Pres, 1982.]

Carmichael, Hoagy [1899 - 1981]Hoagy Carmichael was born Hoagland Howard Carmichael on November 22, 1899 and raised in Bloomington Indiana. He grew up to be a singer and actor but primarily a popular songwriter. His very first composition was called ‘Freewheeling’, and he also wrote a song titled ‘Things Have Changed’. More famously he wrote or co-wrote, among many, many others, ‘Stardust’ and ‘Georgia On My Mind’. Carmichael is one of the many improbable people whose work and persona Dylan admires, possibly just to be perverse. Hoagy’s photo is pinned up on the wall of the shack behind him on the photo by DANIEL KRAMER planned for the US hardback of Dylan’s Tarantula but rejected (it’s reproduced in Kramer’s book Bob Dylan) and in the Empire Burlesque song ‘Tight Connection To My Heart’ Dylan names a Hoagy Carmichael composition. Dylan sings: ‘Well, they’re not showing any lights tonight / And there’s no moon. / There’s just a hot-blooded singer / Singing “Memphis in June”’. ‘Memphis In June’ was composed by Carmichael with lyrics by Johnny Mercer (who also wrote the lyric to ‘Moon River’, which Dylan sang one night on the Never-Ending Tour in tribute to the late STEVIE RAY VAUGHN). Dylan’s ‘hot-blooded singer’ is a neat small joke about Hoagy, whose many assets include a calculatedly lizard-like presence. It was a joke Dylan had retained from an earlier version of the song, then called ‘Someone’s Got A Hold Of My Heart’, which he’d recorded at the sessions for Infidels, the album before Empire Burlesque. At least two performances of this have floated around, but the one eventually released officially, on The Bootleg Series Vols. 1-3 in 1991, offered these alternative lines: ‘I hear the hot-blooded singer / On the bandstand croon / “September Song”, “Memphis in June”’. Clearly Dylan was determined to retain Hoagy, whatever other changes he made. (‘September Song’ was written by Maxwell Anderson and composed by Kurt Weill for the 1938 Broadway play Knickerbocker Holiday.) ‘Memphis’ was written for the 1945 George Raft film Johnny Angel, in which Carmichael played a philosophical singing cab driver. (‘After that I was mentioned for every picture in which a world-weary character in bad repair sat around and sang or leaned on a piano’). Subsequent film roles included being the pianist who sings ‘Hong Kong Blues’ in the Bogart-Bacall film To Have And Have Not, one of Dylan’s favourite hunting-grounds for lyrics in the Empire Burlesque period. The least hot-blooded cover version of ‘Memphis In June’ may be by Matt Monro, from 1962; the best (and ‘on a bandstand croonin’’) may be by Lucy Ann Polk, cut in July 1957 in Hollywood. Hoagy himself recorded the song in 1947 with Billy May & His Orchestra and again in 1956 with a jazz ensemble that included Art Pepper. Carmichael and Mercer also wrote that great song ‘Lazy Bones’ - in twenty minutes, in 1933 - which was revisited magnificently in the 1960s by soul singer James Ray (who made the original US hits of ‘If You Gotta Make A Fool Of Somebody’ and ‘Itty Bitty Pieces’; in the UK he was unlucky enough to find these savaged in unusually distressing ways, even by the standards of British cover versions of the time, by Freddie & The Dreamers and Brian Poole in the first case and by The Rockin’ Berries and Chris Farlowe in the second). Carmichael played ranch-hand Jonesey in the 1959-60 season of the TV series Laramie. In 1972 he was given an Honorary Doctorate by Indiana University back in Bloomington (which is where BETSY BOWDEN got her doctorate for a study of Bob Dylan’s performance art that became her book Performed Literature). Hoagy Carmichael died two days after Christmas, 1981. When a retrospective 4-LP box set of his work, The Classic Hoagy Carmichael, was issued in 1988, with copious notes by John Edward Hasse, Curator of American Music at the Smithsonian Institution, it was released and published jointly by the Smithsonian and the Indiana Historical Society. (American hobbyists are so lucky: there’s always plenty of places to go for funding. Imagine trying to get funds to research, compile and write an accompanying book about Billy Fury from the British Museum and the Birkenhead Historical Society.) The Carmichael box-set notes say this, among much else, and might just remind you of someone else (not Billy Fury): ‘At first listeners may be distracted by the flatness in much of Carmichael’s singing, and turned off especially by his uncertain intonation. The singer himself said, “my native wood-note and often off-key voice is what I call ‘Flatsy through the nose’”. But... one becomes accustomed to these traits and grows to appreciate and admire other qualities of his vocal performances, specifically his phrasing... intimacy, inventiveness and sometimes even sheer audacity. Also, many... evidence spontaneous and extemporaneous qualities, two important ingredients in jazz.’_________

So here's 'Memphis In June' by Hoagy:

And by Lucy Ann Polk:

[Hoagy Carmichael: The Classic Hoagy Carmichael, 4-LP set compiled & annotated by John Edward Hasse; issued as 4 LPs or 3 CDs, BBC BBC 4000 and BBC CD3007, UK, 1988; Johnny Angel, , dir. Edwin L. Marin, written Steve Fisher, RKO, US, 1945. Daniel Kramer: Bob Dylan, New York: Citadel Press edn, 1991, p.127. Betsy Bowden: Performed Literature, Bloomington: Indiana University Pres, 1982.]

Published on November 22, 2014 08:37

November 21, 2014

TRAMPLED BY TURTLES ON THE INTERSTATE

I thought this was too soft - too sentimental - but found there was something compelling about it (helped, perhaps, by the romance of the evocative title) from this bluegrass band from the town of Bob Dylan's birth, Duluth MN. And the sound quality, for a live performance, is formidably good:

Published on November 21, 2014 02:39

November 13, 2014

November 6, 2014

GRACELAND AND ITS "HOUSE NIGGER"

from www.elvispresleyfansofnashville.com

from www.elvispresleyfansofnashville.comIn a recent book-review-based article about Elvis in London Review of Books(accessible here if you’re a subscriber), Ian Penman was in full and fascinating flow - especially in advancing the argument that rather than Elvis having offered, as generally claimed, “black carnality sieved through white restraint” maybe it was more like the opposite: a fusing of “black politeness and white carnality”. He argues that Elvis was essentially placid and biddable - and quotes this from Pamela Clarke Keogh, in her 2004 book Elvis: The Man. The Life. The Legend : “Beneath his extraordinary politeness he has the docility of a house servant”. Penman adds that “it’s hard not to hear in Keogh’s ‘house servant’ the echo of a far less neutral phrase: ‘house nigger’.”

They get there by building far too much on Elvis’ famous politeness - his saying “yes ma’am” and “no sir” to reporters. It wasn’t “extraordinary politeness” and it wasn't particularly black. Every white southerner still talks like that: I was a guest in a home in Georgia only six years ago and its teenage boys, truculent enough in general, called their father “sir” and their mother “ma’am” at the end of every dinner-table sentence. As for Elvis, well yes: he almost never defied the Colonel, and he agreed to record all kinds of crap; yet early on in his career, when he might have been expected to defer to all those record-biz professionals, it was Elvis who took charge at those first recording sessions for RCA, for instance demanding, as Peter Guralnick reports, 31 takes of ‘Hound Dog’ before he was satisfied. He knew exactly what he wanted, from himself and from Scotty Moore, and he insisted on achieving it.

But Penman makes many another point, and with great eloquence, and it’s only in the concluding flourish of his piece, when he envisages Presley’s last days, that he gets careless and makes a mistake that’s often made, describing Elvis as lost, malfunctioning and stranded in “the huge echoing mansion”. A letter in the next issue of London Review of Books corrects this misdescription of Graceland briefly, but I should like to offer rather more detail, from a feature I wrote for the Sunday Telegraph in 2001.

Everyone thinks they know about Graceland. How tacky it is, how redneck vulgar and gross. As a true Elvis fan - who therefore finds it hard to recommend anything he recorded after 1961 - I too came to scoff. I expected it to emanate a lethal mix of Colonel Parker’s Las Vegas Elvis and the stultifying buddy-buddyism of his “Memphis Mafia”, and that my fellow visitors would be obese women in Babar trousers tottering on white high heels under nosecones of sticky hair.

Driving out from downtown along bleak Elvis Presley Boulevard, the first thing you see is Heartbreak Hotel: “A new place to dwell… heart-shaped swimming-pool… affordable rates”. Then the car-parks and an airport terminal’s worth of “facilities”: a vast reception area with Elvis soundtrack, Elvis video screens and long queues for tickets. You file past the Post Office and Burger & Soda Bar to the shuttle buses. Many punters are well-dressed, articulate, young and even black: no odder a crowd than for Alan Bennett (and its average age lower too).

The 42-seater buses arrive incessantly. Headsets guide you on your journey. You can repeat bits and pause at will (though few senior pilgrims manage more than clamping them to their ears). Snippets of hits chime in resourcefully. Setting the unabashed tone, a Deep Heat Rub voice intones: “Just across the street, beyond the stone wall” - it’s brick - “is Graceland Mansion. The shuttle will take you through the famous gates and up to the house.” Here El breaks into “Welcome to my world - won’t you come on in?”, retreating before the narrator’s “You’re about to hear the story of Elvis’ life and phenomenal career. He’ll tell you some of the story himself.” As comically ghoulish as you could wish.

Through the gates and up the hill, you de-bus, thrilled to stare up at those antebellum pillars. The house is so small! It’s a delight. Far from being enormous, enormously vulgar and 1970s, it proves modest and demure - and so strongly redolent of the 1950s that the Elvis whose presence you feel inside is not the bloated figure in the rhinestone jumpsuit but the lithe 22-year-old who first moved in.

It was built by a doctor in 1939 and, excepting those pillars, is altogether restrained: smaller than any Edwardian vicarage and seriously less grandiose than anything Tom Jones or Michael Heseltine would live in.

The entrance hall is ten foot wide, and a few steps in is the five-foot-wide plain staircase. You are not allowed upstairs, “because Elvis never invited visitors up there himself.” It’s a sensible rule - best not to think how people might behave in that death-scene bathroom.

Turn right and you stand in the roped-off entrance to the sitting-room: a modest room with muted pale cream carpet. There’s a 15-foot-long sofa, but it’s neither florid nor overstuffed. Blue closed curtains guard the windows. Cream armchairs sit opposite, flanking a large fireplace with mirrored panels above. The middle of the room is uncluttered space. There’s a long coffee-table, a table-lamp, a tall glass-fronted cabinet. OK, the open double-doorway through to the music room is framed by lurid stained-glass panels depicting peacocks, but the music room itself is small, almost diffident, accommodating an elderly TV set, small sofa, side table and a Story & Clark baby grand as baby as could be.

Off the hall in the other direction is the dining-room, 22 feet by 16. “Around this table,” proclaims the headset, “Elvis shared many evenings of warmth, laughter and storytelling. Everyone at Graceland liked the same downhome southern cooking they grew up with.” Impossible not to contemplate Elvis’ notorious obesity - and that of so many Americans. Yet the room holds no frisson of underclass gross-out. We are at the humble end of Dynastyculture here: gold and purple chairs - but only eight - around an oval metal-edged table sitting on streaked black marble, the mirrored table top matching the walls. A chandelier holds eighteen electric candles.

Down the hallway is Vernon and Gladys’ bedroom: purple clothed headboard and coverlet, bad landscape paintings, old chests of drawers, pink and mauve tiled bathroom, small sad stains on the pale carpet. How little time most visitors spend peering into each room! “Beautiful bedroom.” “Beautiful chandeliers”. “Beautiful.”

It’s not, but it isn’t as bad as millions of American interiors. 1970s unpleasantness hovers, of course: it was the last decade available to him. But the recurrent surprise is how much the Presleys kept faith with 1950s suburbia: their aspiration when Elvis first made it and could rescue them all from their public-housing tenement downtown (itself a climb up from the shotgun shack in Tupelo, Mississippi where Elvis was born in 1935) and the temporary home on Audubon Drive. It’s an unassuming dream and I’m moved by his lifetime loyalty to it.

The kitchen (cue El singing “Get into that kitchen make some noise with the pots ’n’ pans”) is a long slender room with muted wood cabinets and undesigner toaster, coffeepot and eggtimer. It has 1950s simple solidity, and little touches like a small cheery wall-clock, its green face showing limes and lemons. No dentist’s wife would find it good enough if she moved into Graceland today.

Down a narrow staircase with walls and ceiling mirrored we reach the basement TV room, “professionally decorated in 1974 in bright yellow and navy blue”. Again, ’70s ghastliness is undercut by ’50s naivété. The huge white porcelain monkey with black toenails squatting on the coffee table is magicked away by Elvis’ disarmingly inexpensive record-player on a shelf alongside about thirty LPs (the front one by gospel group the Stamps) and lovely old racks of singles not in their sleeves. Three television screens sit side by side, apparently because Elvis read that President Johnson watched all three network news programmes at once.

The basement also holds the den, where 350 yards of multi-coloured fabric entirely cover the walls and ceiling, reminding me of Central Park’s Nirvana Indian restaurant and hippie-tent sumptuousness. Dark blue carpet, red leather chairs, smoky blue snooker table, ostrich feathers, Toulouse-Lautrec poster, Tiffany lighting - its deliberate bombardment confesses that Elvis was touched by the 1960s too. “Wow!”, people exclaim here, “Oh Jesus!…”, “This is wild!” and “Boy, this is a cosy place!”

There’s a bad patch after this: back to ground level via green shagpile-covered stairs with shagpile walls and ceiling. These were once the back steps accessing the yard; but Presley added a family room. In 1974 it got the Indonesian jungle treatment. That monkey belongs here. Dark fur-covered Far Eastern sofas. An ugly teddy on an enormous round chair. Floor and ceiling in, er, green shagpile. Exaggeratedly highbacked chairs carved to look like you’re on drugs when you see them. Ruched curtains. A bare brick wall with dribbling waterfall under red spotlights. This room holds all the later Elvis’ dark paranoid misery. This is what he sank to, fat and isolated in a vortex of self-loathing boredom. Unable to face the world but obliged to record, this room became a makeshift studio. Here in this hell-hole in 1976 he made his last LP.

It’s a relief to get outside, via an annexe converted from the 4-car garage for a special display: a 1960 stereo console; a gold sofa once in the music room; the slightly famous white fake-fur round bed; a model of the Tupelo shack (in the headset, too briefly, Vernon sings “Jimmie Rodgers was born in Dixie”: an eerie authentic hillbilly prefiguring of very early Elvis). Here too is the 1950s desk and furniture from Elvis’ office, touching as well as risible, with its bible, Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet and a consoling Roosevelt quotation about how “it is not the critic that counts, not the man who points out how the strong man stumbled…” The TV shows home-movie footage of Elvis diving incompetently into the pool, and Priscilla doing it perfectly.

Across the homely little yard, past Lisa-Marie’s swings, the garden-shed office where Vernon dealt with fan-mail is another time-warp, with ancient filing-cabinets, a small fridge covered in brown leather like the sofa, and the oldest photocopier I ever saw. This room should be in a proper museum.

Another TV runs Elvis’ post-Army press-conference. He says proudly: “No, sir, I have NO plans for leaving Memphis.”

The back of the house is white and well-proportioned, standing peacably in its several acres of pasture with well-judged trees and horses. The swimming pool is small and pretty; it isn’t shaped like a guitar or a heart and doesn’t shout money or ego. You move on to the chic Italianate meditation garden with its circle of graves where the family now lies oblivious to the constant earthly turmoil.

A shuttle bus returns you to where you began. You head into the black hangar of the car museum. A screen plays the car bits from all his worst films. The cars are excellent, and so is the detailed printed information.

Here is his 1962 Lincoln Continental with gold alligator-hide roof; a black 1975 Dino Ferrari he bought second-hand; the red 1960 MG 1600 used in Blue Hawaii; the batmobile that was his 1971 black Stutz Blackhawk. How nice, if true, that Sinatra had ordered it and Elvis charmed them into reassigning it. Then also a 1973 for which he paid $20,000 up front, leaving, bizarrely, $10,000 owing in instalments. Best of all is the legendary 1955 pink Cadillac Fleetwood, a wondrous colour and gigantic.

You exit, of course, through one of the giftshops. Get your Elvis lunch-box here. Don’t forget your boarding-pass for the Lisa Marie®, Elvis’ aeroplane. It was being readied for another concert date on August 16, 1977, when he died. What sort of plane is it? No executive Lear Jet, nothing state of the art: an ex-Delta Airlines Convair 880 passenger plane. It won’t surprise you that it was manufactured in 1958.

_____© Michael Gray

Published on November 06, 2014 06:05

October 24, 2014

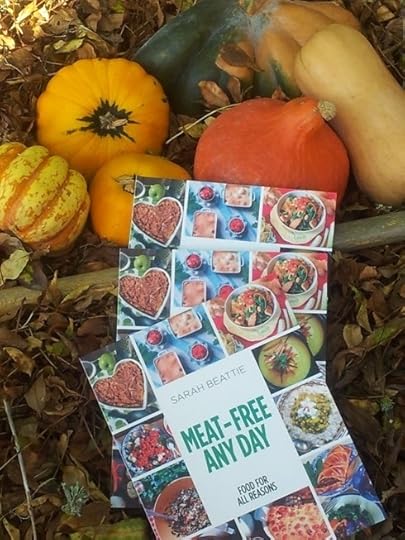

BOB DYLAN WEEKENDS - THE FOOD BOOK

It's Friday, October 24 - which means it's official publication day for Sarah Beattie's new, seventh book, Meat-Free Any Day: Food For All Reasons, published by Select, UK (978-1908256508).

For anyone open-minded about, and truly interested in, food and its great pleasures, this is a compelling collection of imaginative, innovative writing and photography.

It's also a sampler of the food our guests have eaten at the Bob Dylan Discussion Weekends here in Southwest France - food which those guests have written afterwards to rave about like this:

"the food sublime""Wonderful food""delicious meals""Sarah's cooking was brilliant""Sarah's fantastic food""Lovely food""absolutely outstanding""The food was divine"

Obviously I'm not disinterested, but I'm sincere in saying - and I say this as a omnivore - that this is an exceptional book from a superb cook, and you should buy it.

For anyone open-minded about, and truly interested in, food and its great pleasures, this is a compelling collection of imaginative, innovative writing and photography.

It's also a sampler of the food our guests have eaten at the Bob Dylan Discussion Weekends here in Southwest France - food which those guests have written afterwards to rave about like this:

"the food sublime""Wonderful food""delicious meals""Sarah's cooking was brilliant""Sarah's fantastic food""Lovely food""absolutely outstanding""The food was divine"

Obviously I'm not disinterested, but I'm sincere in saying - and I say this as a omnivore - that this is an exceptional book from a superb cook, and you should buy it.

Published on October 24, 2014 05:46

October 5, 2014

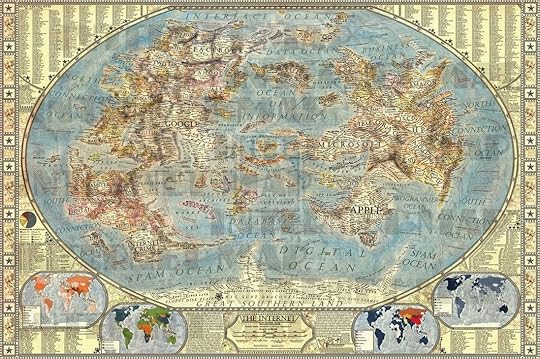

MAP NO. 25: YE OLDE INTERNETE

Published on October 05, 2014 04:06

September 20, 2014

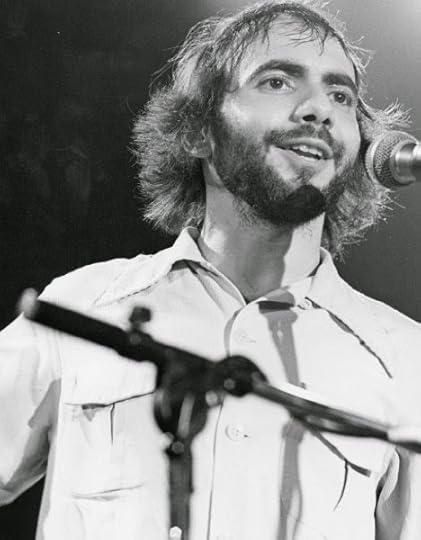

STEVE GOODMAN: 30 YEARS GONE

September 20, 2014: Today it's 30 years - 30 years! - since the sweet-natured, self-deprecating singer-songwriter Steve Goodman died.

Here's the entry on him in The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia:

Goodman, Steve [1948 - 1984]Steve Goodman was born on Chicago’s North Side on July 25, 1948, the son of a used car salesman, about whom Steve eventually wrote the song ‘My Old Man’. He started learning guitar and writing songs as a young teenager and while at Lake Forest College and the University of Illinois he began to perform in a local club, soon dropping out of college (in 1969) to make music his career. In this he was never financially successful, though he survived early on by writing and singing advertising jingles. He returned to Chicago after a short stint trying his luck in Greenwich Village and in 1971 was recorded performing live on a local album, Gathering at the Earl of Old Town. A support spot to KRIS KRISTOFFERSON that April led to a record deal with Buddah and a first album, Steve Goodman, in 1971. Typically, as soon as Goodman had Kristofferson’s attention, he insisted he go and hear another performer who deserved to be discovered too - his friend JOHN PRINE, whose song ‘Donald and Lydia’ Goodman would cover on his own début album. That album also offers Goodman’s signature song, ‘City of New Orleans’, which was a hit not for Goodman but for ARLO GUTHRIE - and then again, the year of Goodman’s death, a hit for WILLIE NELSON. Also on Steve Goodman’s first album is the good-naturedly parody of a country song ‘You Never Even Call Me By My Name’ (which Prine had co-written but wouldn’t take credit for); this too would become a hit, a couple of years later and for David Allen Coe. All this tells the Goodman story: he wrote songs others had hits with, and he was, as writer and performer too, much admired by big-name fellow performers. He was a fine guitarist (he plays on all Prine’s early albums, just as Prine plays on his) and it’s said that when, in solo performances, he broke a guitar string, which was often, he would keep singing while getting a new string out of his pocket, fitting and tuning it, and would then resume his playing unphased - yet he never broke through as a performer himself. In September 1972, with Arif Mardin as producer, Goodman went into Atlantic’s studios in New York to make his second album, Somebody Else’s Troubles, and a single, ‘Election Year Rag’, and for that single, and for the album’s title track, Bob Dylan was a participant. It’s said that Goodman was frustrated at Dylan’s turning up hours and hours late, and perhaps this is why he doesn’t appear on the rest of the material, but he plays piano and sings harmony vocals on these two tracks (both penned by Goodman), along with DAVID BROMBERG on dobro and mandolin, and Prine, among others. The album also included the song that Goodman would come nearest to having a hit with, ‘The Dutchman’ - the one song he didn’t write. When the album was issued, in early 1973, Dylan was credited as Robert Milkwood Thomas. Though Buddah issued The Essential Steve Goodman in 1974 (which also featured ‘Election Year Rag’), it was 1975 before Goodman made his next album, when a label switch gave him greater encouragement and saw an increase in his output. The 1975 album was Jessie’s Jig & Other Favorites; then came Words We Can Dance To (1976), Say It In Private (1977) and High and Outside (1978), which included a duet with then-newcomer Nicolette Larson, and Hot Spot (1980). ‘Chicago Shorty’, as he was dubbed by friends, had also acted as a producer, notably of John Prine’s 1978 album Bruised Orange, and formed his own label, Red Pajama Records, for which he duly recorded Artistic Hair and Affordable Art (both 1983) and his last album, Santa Ana Winds, which reached record stores the day after his death. Goodman had been suffering from leukemia all his adult life, and from Chicago made regular and frequent trips to New York for treatment. He moved to the West Coast (to Seal Beach, just below Long Beach, in Southern California) at the beginning of the 1980s, and received treatment in Seattle. The Artistic Hair album cover depicted him standing in front of a hairdressing salon of that name, his own head bald from the effects of chemotherapy. On August 31, 1984 underwent a bone marrow transpant. Twenty days later he died of the liver and kidney failure brought on by his leukemia in hospital in Seattle. He was 36.

[Steve Goodman: ‘Eight Ball’, ‘Chicago Bust Rag’ & ‘City of New Orleans’, Chicago 1970-71, on Various Artists, Gathering at the Earl of Old Town, Dunwich 670, Chicago, 1971, CD-reissued Mountain Railroad, US, 1989; Steve Goodman, NY, 1971, Buddah BDS-5096, US, 1971-2; Somebody Else’s Troubles, NY, Sep 1972, Buddah BDS-5121, US, 1973; ‘Election Year Rag’, Buddah BDA-326, 1973; Artistic Hair, Red Pajama 001, US, 1983; Affordable Art, Red Pajama 002, 1983; Santa Ana Winds, Red Pajama 003, 1984. Many posthumous recordings have been issued, and CD-reissues of the original LPs, some remastered and with extra tracks. There is also a video, Steve Goodman Live From Austin City Limits…And More!, including Prine, Guthrie & Kristofferson, nia, US, 2003.]

Here's the entry on him in The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia:

Goodman, Steve [1948 - 1984]Steve Goodman was born on Chicago’s North Side on July 25, 1948, the son of a used car salesman, about whom Steve eventually wrote the song ‘My Old Man’. He started learning guitar and writing songs as a young teenager and while at Lake Forest College and the University of Illinois he began to perform in a local club, soon dropping out of college (in 1969) to make music his career. In this he was never financially successful, though he survived early on by writing and singing advertising jingles. He returned to Chicago after a short stint trying his luck in Greenwich Village and in 1971 was recorded performing live on a local album, Gathering at the Earl of Old Town. A support spot to KRIS KRISTOFFERSON that April led to a record deal with Buddah and a first album, Steve Goodman, in 1971. Typically, as soon as Goodman had Kristofferson’s attention, he insisted he go and hear another performer who deserved to be discovered too - his friend JOHN PRINE, whose song ‘Donald and Lydia’ Goodman would cover on his own début album. That album also offers Goodman’s signature song, ‘City of New Orleans’, which was a hit not for Goodman but for ARLO GUTHRIE - and then again, the year of Goodman’s death, a hit for WILLIE NELSON. Also on Steve Goodman’s first album is the good-naturedly parody of a country song ‘You Never Even Call Me By My Name’ (which Prine had co-written but wouldn’t take credit for); this too would become a hit, a couple of years later and for David Allen Coe. All this tells the Goodman story: he wrote songs others had hits with, and he was, as writer and performer too, much admired by big-name fellow performers. He was a fine guitarist (he plays on all Prine’s early albums, just as Prine plays on his) and it’s said that when, in solo performances, he broke a guitar string, which was often, he would keep singing while getting a new string out of his pocket, fitting and tuning it, and would then resume his playing unphased - yet he never broke through as a performer himself. In September 1972, with Arif Mardin as producer, Goodman went into Atlantic’s studios in New York to make his second album, Somebody Else’s Troubles, and a single, ‘Election Year Rag’, and for that single, and for the album’s title track, Bob Dylan was a participant. It’s said that Goodman was frustrated at Dylan’s turning up hours and hours late, and perhaps this is why he doesn’t appear on the rest of the material, but he plays piano and sings harmony vocals on these two tracks (both penned by Goodman), along with DAVID BROMBERG on dobro and mandolin, and Prine, among others. The album also included the song that Goodman would come nearest to having a hit with, ‘The Dutchman’ - the one song he didn’t write. When the album was issued, in early 1973, Dylan was credited as Robert Milkwood Thomas. Though Buddah issued The Essential Steve Goodman in 1974 (which also featured ‘Election Year Rag’), it was 1975 before Goodman made his next album, when a label switch gave him greater encouragement and saw an increase in his output. The 1975 album was Jessie’s Jig & Other Favorites; then came Words We Can Dance To (1976), Say It In Private (1977) and High and Outside (1978), which included a duet with then-newcomer Nicolette Larson, and Hot Spot (1980). ‘Chicago Shorty’, as he was dubbed by friends, had also acted as a producer, notably of John Prine’s 1978 album Bruised Orange, and formed his own label, Red Pajama Records, for which he duly recorded Artistic Hair and Affordable Art (both 1983) and his last album, Santa Ana Winds, which reached record stores the day after his death. Goodman had been suffering from leukemia all his adult life, and from Chicago made regular and frequent trips to New York for treatment. He moved to the West Coast (to Seal Beach, just below Long Beach, in Southern California) at the beginning of the 1980s, and received treatment in Seattle. The Artistic Hair album cover depicted him standing in front of a hairdressing salon of that name, his own head bald from the effects of chemotherapy. On August 31, 1984 underwent a bone marrow transpant. Twenty days later he died of the liver and kidney failure brought on by his leukemia in hospital in Seattle. He was 36.

[Steve Goodman: ‘Eight Ball’, ‘Chicago Bust Rag’ & ‘City of New Orleans’, Chicago 1970-71, on Various Artists, Gathering at the Earl of Old Town, Dunwich 670, Chicago, 1971, CD-reissued Mountain Railroad, US, 1989; Steve Goodman, NY, 1971, Buddah BDS-5096, US, 1971-2; Somebody Else’s Troubles, NY, Sep 1972, Buddah BDS-5121, US, 1973; ‘Election Year Rag’, Buddah BDA-326, 1973; Artistic Hair, Red Pajama 001, US, 1983; Affordable Art, Red Pajama 002, 1983; Santa Ana Winds, Red Pajama 003, 1984. Many posthumous recordings have been issued, and CD-reissues of the original LPs, some remastered and with extra tracks. There is also a video, Steve Goodman Live From Austin City Limits…And More!, including Prine, Guthrie & Kristofferson, nia, US, 2003.]

Published on September 20, 2014 12:58

September 18, 2014

MEAT-FREE ANY DAY

MEAT-FREE ANY DAY is the new book from food writer Sarah Beattie. As some of you may know, Sarah is my wife, so yes, this is a plug - but it truly is a fine book, so allow me to tell you a bit about it...

It contains over 150 recipes, and dozens of colour photographs, all genuinely of the food itself. No glue or plastic, no food-stylist tricks. It's an authentic cookbook for every day, for everyone.

Instead of the usual Starters / Main Courses/ Desserts, the book is, brilliantly, divided into ideal recipes for Sunny Days, for Busy Days, for Sundays, for Hanging on 'til Paydays, for High Days & Holidays, etc., etc.

MEAT-FREE ANY DAY is based on Sarah’s monthly feature in Vegetarian Living magazine, but there’s nothing Worthy or Hair-shirt or Preachy about it. This is modern, imaginative, richly satisfying food, not only for people who never eat meat but for those of us who just like to reduce our meat consumption now & then yet still want quality cuisine when we do.

I've eaten this food - I know how good it is.

MEAT-FREE ANY DAY is published in large-format paperback in the UK on Friday October 24th, at £14.99. You can advance-order it here now: http://tinyurl.com/mpvnmm9 or through your local bookshop. (The ISBN is 978-1908256508.)

PS. You can find Sarah Beattie's Facebook page here .

Published on September 18, 2014 03:24

September 17, 2014

QUAINTNESS OF THE RECENT PAST NO. 39

Published on September 17, 2014 03:05

August 22, 2014

SALE! "BOB DYLAN ENCYCLOPEDIA GREATEST HITS" CD HALF PRICE

Sale! From today the beautifully digipackaged CD Bob Dylan Encyclopedia Greatest Hits is half price for a limited period: £5 + p&p instead of £10 + p&p.

Sale! From today the beautifully digipackaged CD Bob Dylan Encyclopedia Greatest Hits is half price for a limited period: £5 + p&p instead of £10 + p&p.The running-time is 56 minutes 34 seconds. Tracklist is of the author (ie me) reading this varied selection of entries from The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia:

1. 1965-66: Bob Dylan, Pop & the UK Charts [6:19]2. Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat [3:33]3. Being Unable to Die, and Howbeit [3:00]4. Blood On The Tracks [10:49]5. Telegraphy and the Religious Imagination [4:40]6. Eat The Document [4:38]7. Frying An Egg On Stage [0:52]8. Duluth, Minnesota [3:52]9. Musicians' Enthusiasm for Latest Dylan Album, Perennial [0:52]10. Dylan in Books of Quotation [3:31]11. “Love and Theft" [13:35]

Buy it now! from www.michaelgray.net/shop.html

Published on August 22, 2014 08:24