Michael Gray's Blog, page 13

June 13, 2013

ROYAL ALBERT HALL REVISITED: BOB IN EUROPE 2013

Bob Dylan's office has announced his autumn touring schedule in Europe. Significantly, it includes runs of consecutive nights in smaller halls - three nights at Blackpool Opera House, for example, and three nights at London's Royal Albert Hall: the first time he'll have performed there since 1966. The schedule is subject to change, but at present it looks like this:

Oct 10, 2013 Oslo, Norway: SpektrumTickets go on sale Jun 17 09:00am CEST link Oct 12 & 13, 2013 Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm Waterfront Tickets go on sale Jun 19 09:00am CEST link Oct 15 & 16, 2013 Copenhagen, Denmark: Falconer Salen Tickets go on sale Jun 19 09:00am CEST link Oct 18, 19 & 20, 2013 Hannover, Germany: Swiss Life Hall Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Oct 22, 2013 Düsseldorf, Germany: Mitsubishi Electric Halle Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Oct 24 & 25, 2013 Berlin, Germany: Tempodrom Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Oct 28, 2013 Geneva, Switzerland: Geneva Arena Tickets go on sale?? link Oct 30 & 31, 2013 Amsterdam, Netherlands: Heineken Music Hall Jun 14 09:00am CEST Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Nov 02, 03 & 04 2013 Milan, Italy: Teatro degli Arcimboldi Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Nov 06 & 07, 2013 Rome, Italy: Atlantico Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Nov 08, 2013 Padova, Italy: Gran Teatro Geox Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Nov 10, 2013 Brussels, Belgium: Forest National Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Nov 12 & 13, 2013 Paris, France: Teatro Gran Rex Tickets go on sale Jun 21 09:00am CEST link Nov 16, 2013 Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg: Rockhal Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Nov 18, 19 & 20, 2013 Glasgow, Scotland: Clyde Auditorium Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am BST link Nov 22, 23 & 24 2013 Blackpool, England: Opera HouseTickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am BST link Nov 26, 27 & 28 2013 London, England: Royal Albert Hall Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am BST link

More info here.

Oct 10, 2013 Oslo, Norway: SpektrumTickets go on sale Jun 17 09:00am CEST link Oct 12 & 13, 2013 Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm Waterfront Tickets go on sale Jun 19 09:00am CEST link Oct 15 & 16, 2013 Copenhagen, Denmark: Falconer Salen Tickets go on sale Jun 19 09:00am CEST link Oct 18, 19 & 20, 2013 Hannover, Germany: Swiss Life Hall Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Oct 22, 2013 Düsseldorf, Germany: Mitsubishi Electric Halle Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Oct 24 & 25, 2013 Berlin, Germany: Tempodrom Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Oct 28, 2013 Geneva, Switzerland: Geneva Arena Tickets go on sale?? link Oct 30 & 31, 2013 Amsterdam, Netherlands: Heineken Music Hall Jun 14 09:00am CEST Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Nov 02, 03 & 04 2013 Milan, Italy: Teatro degli Arcimboldi Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Nov 06 & 07, 2013 Rome, Italy: Atlantico Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Nov 08, 2013 Padova, Italy: Gran Teatro Geox Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Nov 10, 2013 Brussels, Belgium: Forest National Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Nov 12 & 13, 2013 Paris, France: Teatro Gran Rex Tickets go on sale Jun 21 09:00am CEST link Nov 16, 2013 Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg: Rockhal Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am CEST link Nov 18, 19 & 20, 2013 Glasgow, Scotland: Clyde Auditorium Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am BST link Nov 22, 23 & 24 2013 Blackpool, England: Opera HouseTickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am BST link Nov 26, 27 & 28 2013 London, England: Royal Albert Hall Tickets go on sale Jun 14 09:00am BST link

More info here.

Published on June 13, 2013 05:37

June 10, 2013

June 9, 2013

20 YEARS SINCE ARTHUR ALEXANDER'S DEATH

Not among his better-known tracks - it was one side of a single, coupled with ‘The Other Woman', that was largely ignored (though not by me). As on everything he did, it shines with the most affecting of voices. He'll always be one of my favourite artists, but it's 20 years since his untimely death, at the age of just 53. Here's the entry about him in The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia - for which I was given generous help from Arthur A's biographer, Richard Young:

Alexander, Arthur [1940 - 1993]

Arthur Alexander was born on May 10, 1940 in Florence, Alabama, just five miles from Sheffield and Muscle Shoals. His father played gospel slide guitar (using the neck of a whiskey bottle); his mother and sister sang in a local church choir. Dylan covers Arthur Alexander’s début single, ‘Sally Sue Brown’, made in 1959 and released under his nickname June Alexander (short for Junior), on his Down In The Groove album. You can’t say he pays tribute to Alexander with this, because he makes such a poor job of reviving it... It was really with ‘You Better Move On’ that Arthur Alexander made himself an indispensable artist. He wrote this exquisite classic while working as a bell-hop in the Muscle Shoals Hotel. And then he made a perfect record out of it, produced by Rick Hall at his original Fame studio (an acronym for Florence, Alabama Music Enterprises), which was an old tobacco barn out on Wilson Dam Highway. Leased to Dot Records in 1961, ‘You Better Move On’ was a hit and helped Hall to build his bigger Fame Studio, which later attracted the likes of Aretha Franklin and Wilson Pickett. In 1969 Fame’s studio musicians opened their own independent studio, Muscle Shoals Sound, where Dylan would later make his gospel albums Slow Train Coming and Saved. Despite this hit and its influence on other artists, however, while an EP of his work was highly sought-after in the UK, Arthur Alexander was generally received with indifference by the US public and his career stagnated. After years of personal struggle with drugs and health problems (he was hospitalized several times in the mid-1960s, sometimes at his own request, in a mental health facility in southern Alabama), he returned in the 1970s, first with an album on Warner Brothers and then with a minor hit single in 1975, ‘Every Day I Have To Cry Some’. One of Arthur Alexander’s innovations as a songwriter was the simple use of the word ‘girl’ for the addressee in his songs. When he first used it, it had a function: it was a statement of directness, it instantly implied a relationship; but soon, passed down through LENNON and McCARTNEY to every 1964 beat-group in existence, it became a meaningless suffix, a rhyme to be paired off with ‘world’ as automatically as ‘baby’ with ‘maybe’.

This couldn’t impair the precision with which Arthur Alexander wrote, the moral scrupulousness, the distinctive, careful way that he delineated the dilemmas in eternal-triangle songs with such finesse and economy. All this sung in his unique, restrained, deeply affecting voice. Rarely has moral probity sounded so appealing, so human, as in his work. Listen not only to ‘You Better Move On’ but to the equally impeccable ‘Anna’ and ‘Go Home Girl’ and the funkier but still characteristic ‘The Other Woman’. Arthur Alexander is also one of the many R&B artists whose work was happy to incorporate children’s song, as so much of Dylan’s work does (most especially, of course, the album Under The Red Sky in 1990). Alexander’s 1966 single ‘For You’ incorporates the title line and the next from the children’s rhyming prayer ‘Now I lay me down to sleep’ (the next line is ‘And pray the Lord my soul to keep’), which first appeared in print in Thomas Fleet’s The New-England Primer in 1737. The ROLLING STONES covered ‘You Better Move On’; THE BEATLES covered ‘Anna’; and it was after Arthur Alexander cut Dennis Linde’s song ‘Burning Love’ in 1972 that ELVIS PRESLEY covered that one. Add to that the fact that Dylan covered ‘Sally Sue Brown’, and you have a pretty extraordinary level of coverage for an artist who remains so far from a household name. After his 1975 hit, he went back on the road briefly but didn’t enjoy it; he felt he’d received no money from the record’s success and meanwhile he ‘had found religion and got myself completely straight’, so he quit the music business and moved north. By the 1980s he was driving a bus for social services agency in Cleveland, Ohio, when, to his surprise, Ace Records issued its collection of his early classics, A Shot Of Rhythm and Soul - which included reissue of that first (and by now super-rare) single, ‘Sally Sue Brown’. His attempt at another comeback, in the early 1990s, yielded an appearance at the Bottom Line in New York City, another in Austin, Texas, and the Nonesuch album Lonely Just Like Me, which included several re-recordings. ‘Sally Sue Brown’ was one of them. As on the original ‘You Better Move On’, the musicians included SPOONER OLDHAM. It all came too late. Arthur Alexander died of a heart attack in Nashville on June 9, 1993. A few months earlier, on February 20, his biographer, Richard Younger, went to interview him, at a Cleveland Holiday Inn. ‘He told me,’ wrote Younger, that ‘he had no old photos of himself, nor any of his old records, and had never even heard many of the cover versions of his songs. I had anticipated this and brought along a copy of Bob Dylan’s version of “Sally Sue Brown”. With the headphones pressed to his ears, Arthur moved back and forth in his seat. “Bob’s really rocking,” he said.’ It was a generous verdict. [Arthur Alexander: ‘Sally Sue Brown’, Sheffield AL, 1959, Judd 1020, US, 1960; ‘You Better Move On’ c/w ‘A Shot Of Rhythm And Blues’, Muscle Shoals AL, Oct 2 1961, Dot 16309, US, 1962; ‘Anna’, Nashville, Jul 1962, Dot 16387, 1962; ‘Go Home Girl’, Nashville, c.Sep 1962, Dot 16425, 1963; ‘(Baby) For You’ c/w ‘The Other Woman’, Nashville, 29 Oct 1965, Sound Stage 7 2556, US, 1965; ‘Burning Love’, Memphis, Aug 1971, on Arthur Alexander, Warner Bros. 2592, US, 1972; ‘Every Day I Have To Cry Some’, Muscle Shoals, Jul 1975, Buddah 492, US, 1975; A Shot of Rhythm and Soul, Ace CH66, London, 1982; Nashville, 12-17 Feb 1992, Lonely Just Like Me, Elektra Nonesuch 7559-61475-2, 1993. Special thanks for input & detail to Richard Younger, author of Get a Shot of Rhythm & Blues: The Arthur Alexander Story, Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2000; quote is p.168.]

Published on June 09, 2013 02:07

June 8, 2013

June 6, 2013

WHEN MEDGAR EVERS' BROTHER WANTED TO MEET BOB DYLAN

On May 17, ten years ago, Bob Dylan performed at the Jackson Mississippi JAM - the city's arts and music festival. (Yes, when Freddy Koella was on lead guitar.) What I missed at the time was an account in the Jackson Free Press on June 12, which concentrated not on the music, or the rain and mud, but on the attempt by Medgar Evers' surviving older brother, Charles Evers, to meet Dylan to thank him for the song

‘Only A Pawn in their Game'. I wasn't aware of this story the following year either, when I arrived by train to spend Martin Luther King Jnr. Day in Jackson MS, where I went to Medgar Evers' house and stood at the edge of the suburban lawn where he'd been gunned down just over 40 years earlier.

Now the Jackson Free Press editor, Donna Ladd, has reprinted the story of Charles Evers' attempt to meet Dylan - it was in yesterday's paper - but here I've gone back to the original account, from June 12, 2003. In neither does she explain how Charles Evers is related to Medgar, or that Charles (now 90) came back to Mississippi after his brother's death, took over the local NAACP and became the first black mayor in Mississippi since the Reconstruction period after the American Civil War - she was writing for a local readership who know who Charles Evers was and is - but here's her account:

A bullet from the back of a bush took Medgar Evers' blood.

A hand set the spark

Two eyes took the aim

Behind a man's brain

But he can't be blamed

He's only a pawn in their game.

—“Only A Pawn in their Game,"

Bob Dylan, 1963

It was raining the morning of May 17. I was in my office, worrying about what the Jubilee! JAM organizers must be going through. It's hard to make this festival pay off in good weather, not to mention in times of thunderstorms and crime hysteria. I knew the rain, coming on the JAM's big day—Cassandra Wilson, Bob Dylan and Gerald Levert were scheduled that evening—would be playing hell with the moods of the organizers.

The phone rang me out of my trance. Caller ID said it was Charles Evers, a man who, despite some political differences, has become my friend and partner in attempting to bridge racial gaps. I do his radio show, and this magazine is co-sponsoring the homecoming celebration this year, in honor of his martyred brother. He wrote an opinion piece about the Iraq war for us. “Hi, Mr. Evers."

He got to the point. “Donna, do you think you could help me meet Bob Dylan today? I want to thank him for that song he wrote for Medgar when he was killed."

Gulp. I had no clout that could help Mr. Evers meet Mr. Dylan. I also knew how media-paranoid Dylan is, and that his people had told JAM honcho Malcolm White that he would meet absolutely no one at the JAM so don't bother to ask.

But I also knew what “that song" was, and what it meant when Dylan, seemingly blinking back tears, had sung it at the 1963 March on Washington, two-and-a-half months after a bigot had executed Medgar Evers in Jackson in front of his children: “Daddy! Daddy! Please get up, Daddy!"

I shocked myself by saying, “Sure, Mr. Evers, I'll see what I can do. I bet Dylan would love to meet you." I hung up, promising to call his cell phone with updates.

Throughout the day, as the weather improved and worsened again, my quest didn't go so well. Malcolm—who understood the gravity of the request—promised to ask Dylan's manager, but reiterated the singer's demand not to meet anyone. At 6:30, a half hour before the Dylan show, I checked in again, and Malcolm told me the prospect was bleak. Dylan's manager said he might pass by Mr. Evers and shake his hand if he happened to be standing right there. No media, though. I said this wasn't about me; I'd stay a mile away if I had to; this was about Mr. Evers and Mr. Dylan.

I called Mr. Evers, and talked him into coming to the JAM, even without a guarantee that he'd meet the singer. “I have a pass for you; come watch the show with me, and then we'll see what we can do," I told him, and he said OK. I had a sinking feeling, though, that I might be raising his hopes for nothing—except a good show, of course. I met him in the JRA parking garage, and we walked to the VIP stage, with Mr. Evers stopping to shake black and white hands along the way. I remarked that he might be the biggest celebrity there that night. He laughed and slapped my arm. “No way."

The show was excellent, although truth be known the sound was better down in the mud where we watched the encore. I was a little disappointed, although not surprised, that Dylan didn't seize the opportunity to sing “Only a Pawn in their Game." Looking out at the mostly white crowd, gathered on the AmSouth lawn near where the old segregated Woolworth got its 15 minutes of fame in the 1960s, I told Mr. Evers, “I wish people like Mr. Dylan could understand the progress we're making around here these days." Mr. Evers nodded his head. We both knew that Jackson could handle hearing that song if Dylan could handle doing it for us.

Before the show ended, I checked with JAM organizer Holly Lange about where Mr. Evers should stand to get his shot to thank Mr. Dylan. She shook her head: “I'm sorry. It's just not going to happen. We tried, but they've cleared everyone out of backstage. He won't be able to get back there."

I went back and told Mr. Evers. He shrugged, saying that he'd enjoyed the show anyhow. I asked him to come back to our tent afterward to have his picture taken. He graciously said OK.

Mr. Evers was holding court at the tent, looking like he was running for office again as he waved and shook hands, when Holly appeared in the crowd. “Come. Now." she commanded, breathless from running. I pulled Mr. Evers away from a conversation mid-sentence, and she grabbed his other arm. “Mr. Evers, I'm sorry to do this to you, but we've got to hurry," she said, yanking him through the crowd, me attached to his other arm.

When they let us through the fence, the scene suddenly became quiet and reverent with everyone seemingly scared to blink. I stopped next to Malcolm and Holly. Then Bob Dylan appeared wearing his white cowboy hat. He warmly grasped Mr. Evers' hand and held it for a good five minutes while they talked eye-to-eye, heart-to-heart, man-to-man. They both nodded a lot and seemed emotional. I didn't try to get closer. This was between two giants of the Civil Rights Movement, and the man they—we—had lost to hatred. I blinked back tears.

Suddenly, Mr. Evers turned around and took my arm, pulling me forward. Mr. Dylan slowly turned his gaze to my face and reached for my hand. I shook it, just looking into his eyes, as Mr. Evers told him who I was, that I had a newspaper and that we're trying to bridge racial gaps and do good things in Jackson. My heart was in my toes. “I'm honored to meet you" is all I said.

Then Mr. Evers and I turned and walked away, with him hugging me with boyish delight. He thanked me profusely.

I'm the one who is thankful. To Malcolm and Holly and Dylan's people. And to Mr. Evers for letting me be part of his—and, by extension, Medgar's—special moment.

Another good reason to call Jackson home.[© Donna Ladd, 2003]

With thanks to Andrew Muir for alerting me to the story.

‘Only A Pawn in their Game'. I wasn't aware of this story the following year either, when I arrived by train to spend Martin Luther King Jnr. Day in Jackson MS, where I went to Medgar Evers' house and stood at the edge of the suburban lawn where he'd been gunned down just over 40 years earlier.

Now the Jackson Free Press editor, Donna Ladd, has reprinted the story of Charles Evers' attempt to meet Dylan - it was in yesterday's paper - but here I've gone back to the original account, from June 12, 2003. In neither does she explain how Charles Evers is related to Medgar, or that Charles (now 90) came back to Mississippi after his brother's death, took over the local NAACP and became the first black mayor in Mississippi since the Reconstruction period after the American Civil War - she was writing for a local readership who know who Charles Evers was and is - but here's her account:

A bullet from the back of a bush took Medgar Evers' blood.

A hand set the spark

Two eyes took the aim

Behind a man's brain

But he can't be blamed

He's only a pawn in their game.

—“Only A Pawn in their Game,"

Bob Dylan, 1963

It was raining the morning of May 17. I was in my office, worrying about what the Jubilee! JAM organizers must be going through. It's hard to make this festival pay off in good weather, not to mention in times of thunderstorms and crime hysteria. I knew the rain, coming on the JAM's big day—Cassandra Wilson, Bob Dylan and Gerald Levert were scheduled that evening—would be playing hell with the moods of the organizers.

The phone rang me out of my trance. Caller ID said it was Charles Evers, a man who, despite some political differences, has become my friend and partner in attempting to bridge racial gaps. I do his radio show, and this magazine is co-sponsoring the homecoming celebration this year, in honor of his martyred brother. He wrote an opinion piece about the Iraq war for us. “Hi, Mr. Evers."

He got to the point. “Donna, do you think you could help me meet Bob Dylan today? I want to thank him for that song he wrote for Medgar when he was killed."

Gulp. I had no clout that could help Mr. Evers meet Mr. Dylan. I also knew how media-paranoid Dylan is, and that his people had told JAM honcho Malcolm White that he would meet absolutely no one at the JAM so don't bother to ask.

But I also knew what “that song" was, and what it meant when Dylan, seemingly blinking back tears, had sung it at the 1963 March on Washington, two-and-a-half months after a bigot had executed Medgar Evers in Jackson in front of his children: “Daddy! Daddy! Please get up, Daddy!"

I shocked myself by saying, “Sure, Mr. Evers, I'll see what I can do. I bet Dylan would love to meet you." I hung up, promising to call his cell phone with updates.

Throughout the day, as the weather improved and worsened again, my quest didn't go so well. Malcolm—who understood the gravity of the request—promised to ask Dylan's manager, but reiterated the singer's demand not to meet anyone. At 6:30, a half hour before the Dylan show, I checked in again, and Malcolm told me the prospect was bleak. Dylan's manager said he might pass by Mr. Evers and shake his hand if he happened to be standing right there. No media, though. I said this wasn't about me; I'd stay a mile away if I had to; this was about Mr. Evers and Mr. Dylan.

I called Mr. Evers, and talked him into coming to the JAM, even without a guarantee that he'd meet the singer. “I have a pass for you; come watch the show with me, and then we'll see what we can do," I told him, and he said OK. I had a sinking feeling, though, that I might be raising his hopes for nothing—except a good show, of course. I met him in the JRA parking garage, and we walked to the VIP stage, with Mr. Evers stopping to shake black and white hands along the way. I remarked that he might be the biggest celebrity there that night. He laughed and slapped my arm. “No way."

The show was excellent, although truth be known the sound was better down in the mud where we watched the encore. I was a little disappointed, although not surprised, that Dylan didn't seize the opportunity to sing “Only a Pawn in their Game." Looking out at the mostly white crowd, gathered on the AmSouth lawn near where the old segregated Woolworth got its 15 minutes of fame in the 1960s, I told Mr. Evers, “I wish people like Mr. Dylan could understand the progress we're making around here these days." Mr. Evers nodded his head. We both knew that Jackson could handle hearing that song if Dylan could handle doing it for us.

Before the show ended, I checked with JAM organizer Holly Lange about where Mr. Evers should stand to get his shot to thank Mr. Dylan. She shook her head: “I'm sorry. It's just not going to happen. We tried, but they've cleared everyone out of backstage. He won't be able to get back there."

I went back and told Mr. Evers. He shrugged, saying that he'd enjoyed the show anyhow. I asked him to come back to our tent afterward to have his picture taken. He graciously said OK.

Mr. Evers was holding court at the tent, looking like he was running for office again as he waved and shook hands, when Holly appeared in the crowd. “Come. Now." she commanded, breathless from running. I pulled Mr. Evers away from a conversation mid-sentence, and she grabbed his other arm. “Mr. Evers, I'm sorry to do this to you, but we've got to hurry," she said, yanking him through the crowd, me attached to his other arm.

When they let us through the fence, the scene suddenly became quiet and reverent with everyone seemingly scared to blink. I stopped next to Malcolm and Holly. Then Bob Dylan appeared wearing his white cowboy hat. He warmly grasped Mr. Evers' hand and held it for a good five minutes while they talked eye-to-eye, heart-to-heart, man-to-man. They both nodded a lot and seemed emotional. I didn't try to get closer. This was between two giants of the Civil Rights Movement, and the man they—we—had lost to hatred. I blinked back tears.

Suddenly, Mr. Evers turned around and took my arm, pulling me forward. Mr. Dylan slowly turned his gaze to my face and reached for my hand. I shook it, just looking into his eyes, as Mr. Evers told him who I was, that I had a newspaper and that we're trying to bridge racial gaps and do good things in Jackson. My heart was in my toes. “I'm honored to meet you" is all I said.

Then Mr. Evers and I turned and walked away, with him hugging me with boyish delight. He thanked me profusely.

I'm the one who is thankful. To Malcolm and Holly and Dylan's people. And to Mr. Evers for letting me be part of his—and, by extension, Medgar's—special moment.

Another good reason to call Jackson home.[© Donna Ladd, 2003]

With thanks to Andrew Muir for alerting me to the story.

Published on June 06, 2013 04:58

May 26, 2013

JIMMIE RODGERS DIED 80 YEARS AGO

Here's my entry on Rodgers in The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia:

Rodgers, Jimmie [1897 - 1933]

Jimmie Rodgers was born in Meridian, Mississippi on September 8, 1897, disproving General Sherman’s post-march announcement of the 1860s that ‘Meridian no longer exists!’ Rodgers, looking in his publicity pictures like a cross between Bing Crosby and Stan Laurel, was ‘the father of country music’ yet was mesmerised by the blues, a genre to which he contributed and with which he became familiar from working alongside black railroad labourers. Hence his other appellation, ‘the Singing Brakeman’.

(The railroad line, and even the train, still runs through Meridian, which is built on a rise. The track crosses a wide street that climbs to tall, elderly buildings, some of which must have gone up during Jimmie’s childhood.)

Rodgers, the inventor of the Blue Yodel, had a short life and a brief career. He had already contracted tuberculosis and had to give up his dayjob by the time he was discovered and first recorded by Ralph Peer in 1927, and his last session was 36 hours before his death, which was in New York on May 26, 1933. In the five and a half years in which he recorded he cut 110 sides. You can get them all on a 6-CD set.

At least he enjoyed stardom while he lived, as well as posthumously. Recognised in his own lifetime as having initiated an important idiom, it has proved enduring since. His records were astoundingly popular, selling in huge numbers, and he became the first rural artist to match the commercial success of Northern popular singers.

His fame in segregated Mississippi sometimes had surprising results. At the huge and wanky King Edward Hotel in downtown Jackson, Rodgers, hearing marvellous Tommy Johnson and Ishman Bracey on the street, brought them up to the hotel roof to perform for his own audience. This black ragamuffin act, plucked off the street, bemused the supper-club crowd, but Rodgers knew talent when he heard it.

This is what Bob Dylan said of him in the Biograph interview of 1985: ‘The most inspiring type of entertainer for me has always been somebody like Jimmie Rodgers, somebody who could do it alone and was totally original. He was combining elements of blues and hillbilly sounds before anyone else had thought of it. He recorded at the same time as Blind Willie McTell but he wasn’t just another white boy singing black. That was his great genius and he was there first...he played on the same stage with big bands, girly choruses and follies burlesque and he sang in a plaintive voice and style and he’s outlasted them all.’

As early as May 1960, and again that fall, Dylan was recorded performing Rodgers’ ‘Blue Yodel No. 8 (Muleskinner’s Blues)’ in Minneapolis, and ‘Southern Cannonball’ in East Orange, New Jersey in February or March 1961. The Rodgers influence on the young Dylan was perhaps not wholly beneficial. The repulsively maudlin ‘Hobo Bill’s Last Ride’ (written by West Texas farm boy Waldo O’Neal, and, at his sister’s urging, submitted cold to Rodgers in 1928) influenced Dylan’s deservedly obscure ‘Only A Hobo’. Both lyrics make the same crude attempt at rhetoric, in protest-singer-saintly style: ‘just another railroad bum...’, whines Rodgers; ‘Only a hobo...’, whines Dylan. As Rodgers sings it, though, the melody for ‘Hobo Bill’s Last Ride’ shares quite a bit with that of ‘I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night’, which is, in turn, the song behind Dylan’s own ‘I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine’ - in which altogether more complex issues of saintliness, and guilt, come in for a fine, detached scrutiny, light-years ahead of either ‘Only A Hobo’ or ‘Hobo Bill’s Last Ride’.

Dylan and Johnny Cash’s duets, recorded in Nashville on February 19, 1969, included ‘Blue Yodel No.1’ and ‘Blue Yodel No.5’, and it may have been from their presence in ‘Blue Yodel No.12’, recorded a week before Rodgers’ last session, that Dylan took the essentially commonstock couplet ‘I got that achin’ heart disease / It works just like a cancer, it’s killin’ me by degrees’ and re-processed it into his own line ‘Horseplay and disease are killin’ me by degrees’ on ‘Where Are You Tonight (Journey Through Dark Heat)?’ on Street Legal.

Mules’ years later, Dylan went into the studios in Chicago in June 1992 and recorded, among other things (see Bromberg, David) Rodgers’ ‘Miss The Mississippi and You’. It is one of only four tracks from that session to have circulated. In Memphis, two years later, he recorded Rodgers’ ‘My Blue-Eyed Jane’ for a tribute album that was, reportedly, a project Dylan initiated. We first heard a tantalising snatch of one take on the CD-ROM Highway 61 Interactive in 1995, its woodsmoke guitars making it sound almost like an outtake from New Morning; a second complete take circulated among collectors in 1996, on which shared vocals by Emmylou Harris had been overdubbed in the interim; and then later that year a third version, with Dylan’s vocal re-recorded and Harris’ removed, supplanted both, and saw release on what turned out to be the first release on Dylan’s own Egyptian Records label, in the collection finally issued as The Songs Of Jimmie Rodgers - A Tribute.

More recently still, Dylan pays Rodgers the further tribute of impersonating him, in jest, on a re-recording of a Slow Train Coming song with Mavis Staples (see the entry ‘Gonna Change My Way Of Thinking’ [2003 version]); and in 2004, in Chronicles Volume One, Dylan returns us to the beginning of Rodgers’ impact upon him, which he says was back in Hibbing, in the days before his earliest performances of the material:

‘One of the reasons I liked going there [to Echo Helstrom's house], besides puppy love, was that they had Jimmie Rodgers records, old 78s in the house. I used to sit there mesmerized, listening to the Blue Yodeler, singing, “I’m a Tennessee hustler, I don’t have to work.” I didn’t want to have to work, either.’

[Jimmie Rodgers: complete recorded works, from ‘The Soldier’s Sweetheart’, Bristol TN, 4 Aug 1927, to ‘Years Ago’, NY, 24 May 1933, on The Singing Brakeman, Bear Family BCD 15540-FH, Germany, 1992. Bob Dylan: ‘Miss the Mississippi and You’, Chicago, 4-21 Jun 1992, unreleased; ‘My Blue-Eyed Jane’, Memphis, 9 May 1994, vocals re-recorded unknown location early May 1997, The Songs Of Jimmie Rodgers - A Tribute, Various Artists, Egyptian/Columbia Records 485189 2, NY, 1997. Bob Dylan: Chronicles Volume One, 2004, p.59. The book on Rodgers is Nolan Porterfield’s Jimmie Rodgers: the Life and Times of America’s Blue Yodeler, Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1979.]

Published on May 26, 2013 07:46

May 25, 2013

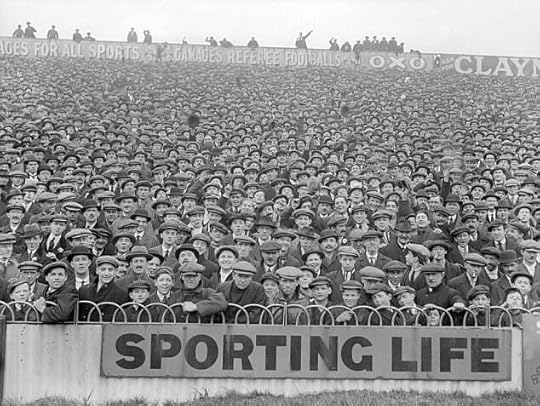

QUAINTNESS OF THE RECENT PAST NO.32

Published on May 25, 2013 07:56

May 24, 2013

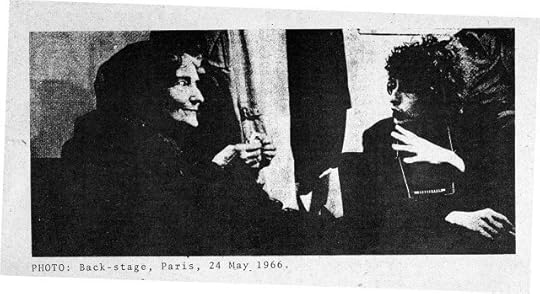

72: UPDATE ON PHOTO LOCATION

photo & caption taken from Praxis: One by Stephen Pickering, Santa Cruz, CA: No Limit Publications, 1971 - the first edition of a book, now rare, which is full of brilliant pictures - photographer uncredited. Update: since posting this yesterday, I've been told that the caption typed under the photo when published in Praxis: One is incorrect:

photo & caption taken from Praxis: One by Stephen Pickering, Santa Cruz, CA: No Limit Publications, 1971 - the first edition of a book, now rare, which is full of brilliant pictures - photographer uncredited. Update: since posting this yesterday, I've been told that the caption typed under the photo when published in Praxis: One is incorrect:Harold Lepidus of Bob Dylan Examiner shared my post on his Facebook page and received this response from a Bob Stacy:

Most definitely, it’s NOT Paris, May 24, 1966, as S. Pickering had captioned in his publication. There are several photos with Bob and the lady. I think all or most of those were taken by Barry Feinstein. There’s one in Feinstein’s Real Moments photo book. It says Birmingham, (May 12) 1966 - “This old lady who sold flowers came in and they really hit it off. He loved to gab with older people.”

The grande old dame even made the final cut in Bob’s Eat The Document film.

At one point, he asks her, “Did you like ‘Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues’? That’s what I’m asking you. Do you remember the song? Perhaps you don’t remember it?”

Flower Lady: “I never recognized you with your ... wig.”

(Closing door - end scene ... tough review, possibly one of the rare times Dylan was left totally speechless on that tour.)

So if it was Birmingham, he was “not even 25"...

Published on May 24, 2013 01:07

72

photo & caption taken from Praxis: One by Stephen Pickering, Santa Cruz, CA: No Limit Publications, 1971 - the first edition of a book, now rare, which is full of brilliant pictures - photographer uncredited.

photo & caption taken from Praxis: One by Stephen Pickering, Santa Cruz, CA: No Limit Publications, 1971 - the first edition of a book, now rare, which is full of brilliant pictures - photographer uncredited.

Published on May 24, 2013 01:07

May 22, 2013

REGINA McCRARY: HAPPY 55th

Gospel singer Regina McCrary, an old friend of Bob Dylan's, is 55 today (May 22, 2013). Here's her entry in The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia (but updated for this blogpost):

Gospel singer Regina McCrary, an old friend of Bob Dylan's, is 55 today (May 22, 2013). Here's her entry in The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia (but updated for this blogpost):McCrary, Regina [1958 - ]

Regina McCrary (sometimes billed under her previous married names Regina Havis and Regina McCrary Brown) was born May 22, 1958 in Nashville, the daughter of the late Rev. Samuel Brown, who as Sam McCrary was lead singer of the Fairfield Four gospel group in the 1940s. The group had been formed in the 1920s; re-formed in the 1980s, the Fairfield Four performs ‘Lonesome Valley’ on the soundtrack of the film O Brother, Where Art Thou?. The younger sister of gospel-singer Ann McCrary, she was encouraged to audition for a place in Dylan’s back-up singers’ group by her friend Carolyn Dennis, whom she had known since they were small children. She auditioned when the 1978 World Tour hit Nashville on December 2, almost at the end of its long run - and she was brought in for the sessions for Slow Train Coming in spring 1979, beginning with vocal overdubs in the Muscle Shoals studio in Sheffield, Alabama that May 5 and continuing on May 7, 10 and 11. Next, the very beautiful Ms McCrary Brown formed part of the back-up singing outfit on Dylan’s ‘Saturday Night Live’ appearance on October 20, 1979 and then embarked on the first Dylan gospel tour, starting with the long run of sold-out dates at the Fox Warfield in San Francisco that November 1 and finishing on December 9 in Tucson, Arizona. She had no idea how ‘big’ Bob Dylan was when she signed up with him: it was only when confronted with these audiences that she registered how important a figure he was to so many people. Her friend Carolyn Dennis was not in the group on this tour: Regina’s vocal colleagues were Mona Lisa Young and Helena Springs. The group sang some opening numbers each night before Dylan himself came on, but he plunged Regina in at the deep end by making her deliver as a monologue a particular ‘Christian homily’ story she’d known all her life and had been heard retailing backstage. In 1980 McCrary stayed on the Dylan payroll, remaining all through the year’s touring - from snowy Portland, Oregon on January 11 through to Charleston, West Virginia on February 9, and from Toronto on April 17 through to Dayton, Ohio on May 21. She was there too for the recording of the Saved album in between the two tours, beginning in the studio on February 13, along with Mona Lisa Young and Clydie King, and she sang behind Dylan on ‘Gotta Serve Somebody’ at the Grammy awards show on CBS-TV in LA that February 27. (In March, when Dylan played harmonica on Keith Green’s track ‘Pledge My Head To Heaven’, two other McCrary sisters, Charity and Linda, were the back-up singers.) On the second 1980 tour, she duetted with Dylan on his little-known song ‘Ain’t No Man Righteous, No Not One’ at Hartford, Connecticut on May 7, and two weeks later sang it solo on the tour’s last night. Again, this tour did not include Carolyn Dennis. In 1981 Regina McCrary was still with Dylan when he went into the studios in Santa Monica on March 11 to start work on the Shot of Love sessions, and towards the end of that month during one day’s session she not only sang back-up vocals but was recorded singing solo lead vocals on ‘Please Be Patient With Me’ and (as she had done live the year before) ‘‘Ain’t No Man Righteous, No Not One’. She and Dylan even co-wrote a song at these sessions, ‘Got To Give Him My All’ (though it has never circulated, by either singer). She remained at the sessions until May, though she seems to have left before the last session, at which were Carolyn Dennis and Madelyn Quebec but no Regina. On the June-July 1981 tour, Regina was there again, and sang solo lead vocal on ‘Till I Get It Right’ in an early slot at each concert, and duetted with Dylan on ‘Mary From the Wild Moor’ at the third London performance on June 28. In all, she had been with Bob Dylan on three albums and over 150 concerts. By 1999, when interviewed for the US Dylan fanzine On The Tracks, McCrary Brown was working ‘as a drug counselor in a Christian ministry’ and singing on ‘The Bobby Jones Gospel Show’, then the largest gospel TV show in the country, which went out twice each Sunday via cable TV channel BET from Nashville, her home base. McCrary’s 21-year-old son Tony was murdered in c2000, but she reportedly found peace by inwardly forgiving his killer. By 2004 she had become the Rev. Regina McCrary and was billed as a guest speaker at the Surviving Heartbreak Hotel Women’s Retreat, again in Nashville. In 2003, a circle of sorts was completed with the release of the various-artists compilation album Gotta Serve Somebody: The Gospel Songs of Bob Dylan, which features two relevant items (alongside Dylan’s own duet with Mavis Staples): here we find an a cappella ‘Are You Ready?’ by the newest incarnation of the all-male Fairfield Four - and a version of ‘Pressing On’ billed as by the Chicago Mass Choir on which the lead vocalist is . . . Regina McCrary. Since then, as part of gospel group the McCrary Sisters, she has continued to perform and record gospel albums. Our Journey, from 2010, includes a re-working of ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’.

Published on May 22, 2013 05:19