Max McCoy's Blog: Max McCoy, page 2

March 3, 2010

The $46 man

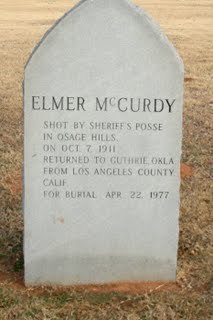

One of Doolin's neighbors in Summit View is a lesser outlaw by the name of Elmer McCurdy, killed in a gunfight with lawmen after a train robbery in the Osage Hills on Oct. 7, 1911. McCurdy's body wasn't buried for another 65 years, however -- his corpse was mummified and spent decades touring the country in carnivals and spookhouses. It was finally identified as human remains at an amusement park in Long Beach, California, in 1976, during the filming of an episode of "The Six Million Dollar Man," and returned to Guthrie for burial. Oh, and what did McCurdy get during that 1911 train robbery? Forty-six dollars and some liquor.[image error]

One of Doolin's neighbors in Summit View is a lesser outlaw by the name of Elmer McCurdy, killed in a gunfight with lawmen after a train robbery in the Osage Hills on Oct. 7, 1911. McCurdy's body wasn't buried for another 65 years, however -- his corpse was mummified and spent decades touring the country in carnivals and spookhouses. It was finally identified as human remains at an amusement park in Long Beach, California, in 1976, during the filming of an episode of "The Six Million Dollar Man," and returned to Guthrie for burial. Oh, and what did McCurdy get during that 1911 train robbery? Forty-six dollars and some liquor.[image error]

Published on March 03, 2010 19:31

Dead like Doolin

Bill Doolin, Outlaw O.T. (Oklahoma Territory), was killed by a posse led by Heck Thomas near Lawson on Aug. 25, 1896, after escaping from the federal jail at Guthrie a few weeks earlier. Accounts differ as to who fired the fatal shot, but all agree that Doolin was hit with a fatal blast of buckshot from an eight-gauge shotgun. The results were documented by the local photographer, as was the fashion, and for a quarter you could buy a postcard of Doolin in death -- with the proceeds ostensibly going to his widow, Edith, for burial expenses (although none of the money collected went for that purpose). Doolin was buried in Summit View Cemetery at Guthrie, and his grave marked with a bent buggy axle.

Bill Doolin, Outlaw O.T. (Oklahoma Territory), was killed by a posse led by Heck Thomas near Lawson on Aug. 25, 1896, after escaping from the federal jail at Guthrie a few weeks earlier. Accounts differ as to who fired the fatal shot, but all agree that Doolin was hit with a fatal blast of buckshot from an eight-gauge shotgun. The results were documented by the local photographer, as was the fashion, and for a quarter you could buy a postcard of Doolin in death -- with the proceeds ostensibly going to his widow, Edith, for burial expenses (although none of the money collected went for that purpose). Doolin was buried in Summit View Cemetery at Guthrie, and his grave marked with a bent buggy axle.Today, Doolin's grave is marked with an impressive red tombstone that is about as tall as I am (see left), in an area marked with a cheesy "Boot Hill" sign in Summit View. By all accounts, Doolin was among the most likeable of western outlaws, and claimed to have never killed anybody during any of his many robberies, at least not on purpose.[image error]

Published on March 03, 2010 18:59

December 29, 2009

Territorial prison gallery

Here's the front of the old territorial prison at Guthrie, on the northeast corner of Second and Noble. This was the place that Bill Doolin escaped from in 1896 -- and which plays a central role in my new novel, DAMNATION ROAD. Underneath that pink stucco, which was added after the local Methodists bought the building for a church in 1924, is native red sandstone. About where you see the window in this photo was the main entrance to the jail, an iron cage attached to the outside of the building that was reached by a flight of steep iron steps. In some of the literature, you see this referred to as the "black jail" of Guthrie, but that was an earlier county jail, which was built from black strap iron. After the Methodists purchased the building, they added the stucco, a peaked roof, and a church-like addition on the east end to make it appear less like a fortress. After it was abandoned by the Methodists, it was home to the Samaritan Foundation, a religious cult, until 1995. The building has been declared unsafe and is closed to the public, although there is an restoration movement planned, according to a sign on the corner of the building. The jail, as you might expect, is reported to be haunted.

Here's the front of the old territorial prison at Guthrie, on the northeast corner of Second and Noble. This was the place that Bill Doolin escaped from in 1896 -- and which plays a central role in my new novel, DAMNATION ROAD. Underneath that pink stucco, which was added after the local Methodists bought the building for a church in 1924, is native red sandstone. About where you see the window in this photo was the main entrance to the jail, an iron cage attached to the outside of the building that was reached by a flight of steep iron steps. In some of the literature, you see this referred to as the "black jail" of Guthrie, but that was an earlier county jail, which was built from black strap iron. After the Methodists purchased the building, they added the stucco, a peaked roof, and a church-like addition on the east end to make it appear less like a fortress. After it was abandoned by the Methodists, it was home to the Samaritan Foundation, a religious cult, until 1995. The building has been declared unsafe and is closed to the public, although there is an restoration movement planned, according to a sign on the corner of the building. The jail, as you might expect, is reported to be haunted.

Wide shot

Here's a shot of the entire building. The old entrance is on the left (west) side of this photo, facing west. The original prison building did not have a green peaked roof, nor did it have the church-like addition on the east side.

Original building

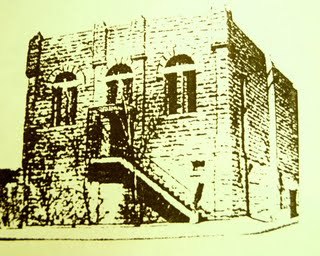

Original buildingHere's what the territorial jail originally looked like in the 1890s, from a photo in the Oklahoma Historical Society Archives. Look closely and you can see the steps leading up to the iron cage and main entrance on the second floor.

One last shot

One last shotHere's a tiny barred window that is on the ground floor of the prison, visible on the old photo just above the bottom of the steps. This was a special cell sometimes used for female prisoners, usually prostitutes, if I'm reading my sources correctly.

Did I encounter any ghosts while visiting the old territorial prison? Well, no. But there was a decidedly weird and malevolent vibe to the place -- but maybe that's just because I knew a little history. Oh, and what happened to Bill Doolin, the famous Oklahoma Territory outlaw who famously broke out in 1896? I'll save that story for my next post...

[image error]

Published on December 29, 2009 20:03

Haunted jail

Here's the front (west) side of the old federal jail at Guthrie, on the northeast corner of Second and Noble. This was the jail that Bill Doolin escaped in 1896 -- and which plays a central role in my new novel, DAMNATION ROAD. Underneath that pink stucco, which was added after the local Methodists bought the jail for a church in 1924, is native red sandstone. About where you see the window in this photo was the main entrance to the jail, an iron cage attached to the outside of the building t...

Here's the front (west) side of the old federal jail at Guthrie, on the northeast corner of Second and Noble. This was the jail that Bill Doolin escaped in 1896 -- and which plays a central role in my new novel, DAMNATION ROAD. Underneath that pink stucco, which was added after the local Methodists bought the jail for a church in 1924, is native red sandstone. About where you see the window in this photo was the main entrance to the jail, an iron cage attached to the outside of the building t...

Published on December 29, 2009 20:03

December 11, 2009

Holiday shooter

Here's something that made me smile, even though I hate this time of year (I know, I know, call me Scrooge). It's a holiday self-portrait from T. Rob Brown, my friend and former colleague at The Joplin Globe. I worked with Brown for many years at the Globe, and he often accompanied me on several investigative pieces. He was named AP Photographer of the Year for 2009. The holiday greeting wasn't taken with a fisheye, by the way -- it's his reflection in a Christmas ornament.

Here's something that made me smile, even though I hate this time of year (I know, I know, call me Scrooge). It's a holiday self-portrait from T. Rob Brown, my friend and former colleague at The Joplin Globe. I worked with Brown for many years at the Globe, and he often accompanied me on several investigative pieces. He was named AP Photographer of the Year for 2009. The holiday greeting wasn't taken with a fisheye, by the way -- it's his reflection in a Christmas ornament.

Published on December 11, 2009 21:00

December 9, 2009

All in the lead

This, from CNN today: "President Obama -- fighting wars in two countries -- will arrive in Norway on Thursday to accept the Nobel Peace Prize for 2009."

Published on December 09, 2009 10:26

November 11, 2009

Time, Date, Twitter

As if journalism students didn't have enough trouble already, there's a fake AP Stylebook on Twitter. But at least some of the 140-character entries are amusing. Consider this: The numbers one through ten should be spelled out while numbers greater than ten are products of the Illuminati and should be avoided.

Published on November 11, 2009 15:44

October 27, 2009

Pedestrian Comics

I seem to be blogging a lot, probably to keep from writing. Well, here's something I've been meaning to post for a while now -- Pedestrian Comics by Dan Spees. It's an autobiographical take on his life teaching community college at Hutchinson, Kansas. I particularly like the panels where he is sent to teach composition at a local Catholic school.

I seem to be blogging a lot, probably to keep from writing. Well, here's something I've been meaning to post for a while now -- Pedestrian Comics by Dan Spees. It's an autobiographical take on his life teaching community college at Hutchinson, Kansas. I particularly like the panels where he is sent to teach composition at a local Catholic school.

Published on October 27, 2009 19:32

October 26, 2009

A Remarkable Ego

Here's a book review I did for the Spring 2009 issue of The Great Plains Newsletter. This post is way too long, according to the blog gurus, but to hell with them. The newsletter isn't available online, so thought I'd offer it here.

Here's a book review I did for the Spring 2009 issue of The Great Plains Newsletter. This post is way too long, according to the blog gurus, but to hell with them. The newsletter isn't available online, so thought I'd offer it here.A Remarkable Curiosity: Dispatches from a New York City Journalist's 1873 Railroad Trip Across the American West. Edited and compiled by Jerald T. Milanich. Boulder: The UP of Colorado, 2008, 371 pages, with index and illustrations.

Although few have heard of him now, Amos Jay Cummings was once the most popular journalist in the United States. More than a hundred years after his death, dispatches from his 1873 railway journey across the American west have been collected by anthropologist Jerald T. Milanich.

Milanich, curator of archaeology at the Florida Museumof Natural History at Gainesville, became interested in Cummings when he read an unsigned newspaper account of a visit to Turtle Mound, a huge shell heap left by ancient Indians on the Atlantic coast. Intrigued, Malevich found phraseology similar to the Turtle Mound article in an 1875 guidebook to Florida that was authored by ���Ziska,��� an obvious pseudonym.

After what Malevich describes as a ���wild literary adventure,��� he confirmed that Ziska was in fact Amos J. Cummings ��� journalist, Civil War hero, and Congressman.

And, one might add, liar and shameless self-promoter.

Cummings was born in 1838 in a small town near border between Pennsylvania and New York. He claimed to have run away at 15 to become an ���itinerant typesetter,��� although this is certainly an exaggeration, a stretcher told by Cummings in his later years to make his life seem more romantic. He also claimed to have accompanied William Walker during the 1858 invasion of Nicaragua, but Malevich is rightly suspicious ��� neither the dates nor the details add up to allow Cummings to have been with Walker during any of his ill-fated attempts to establish a slave-holding Southern empire in Latin America.

During the Civil War, Cummings was a volunteer with a New Jersey infantry regiment, and saw action at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. Thirty years after the war ��� and following his election to Congress ��� he received the Medal of Honor for leading a charge to save a Union gun from falling into rebel hands during the battle of Salem Church on May 4, 1863.

Milanich concludes that Cummings was a ���bona fide war hero��� because about a third of the 35 New Jersey soldiers who were awarded the medal got theirs long after the war, too. But the most complete account of the feat of heroism that saved the cannon appears to have penned by ��� you guessed it ��� Cummings himself.

���One thing I soon learned,��� Milanich writes in a classic bit of understatement, ���was that Cummings and his biographers did not always provide correct or truthful information.���

The stretchers include moving his year of birth to 1841, apparently to make Cummings appear younger. The reason, Milanich, believes, was vanity. After his success as a travel writer sending back anonymous dispatches from wild and wooly Florida, Cummings (who was managing editor of The New York Sun) undertook the six-month railway journey to the west. It was during this journey that he began filing his dispatches under Ziska.

Alas, Milanich never discovered why Cummings chose the odd pseudonym.

���I���ve been trying to figure it out since I first discovered that Ziska was Cummings,��� Milanich said in an email message. ���Had I been a reasonably literate person in 1873 I probably would know immediately, but.. . .���

While such affected journalistic handles were common during the period, Ziska no longer rings like the pen name of one of his travel writing contemporaries, Mark Twain. His prose pales in comparison as well, which may be much of the reason Cummings is forgotten and Twain is not. To say that his style is dry is like saying that rain is wet.

���The trip by railroad over the plains is monotonous,��� Cummings reports from Kansas. ���It is generally understood that passengers have not a thing to do during the journey but to gaze at immense buffalo herds and shoot antelopes.

Although it was in the buffalo season, I saw none of the animals.���

Still, there is much historical value in his accounts. The best example may be an interview Cummings did in July 1873 at Salt Lake City with Brigham Young. The 78-year-old patriarch was being sued for divorce and $200,000 by his seventeenth wife, Ann Eliza.

���I had a talk with the Mormon Prophet yesterday,��� Cummings begins, and goes on to provide a detailed account of his reception: ���I saw the great Religious Chief sitting on a sofa before I entered the room. I recognized him from the pictures that I had seen hanging at the doors of the Salt Lake photograph galleries. He was looking toward the stoop, and evidently expecting me. He kept his eyes fixed upon me as I approached, then he arose, shook hands, politely offered me his seat upon the sofa, and sat down upon a chair at my side.���

A sort of transcript follows, and when Cummings asks about the divorce suit, Young explodes.

���Blackmail! Blackmail! It is not the first time they have attempted to Blackmail the Mormon Church, and I presume it will not be the last. We have never allowed them to blackmail us out of a single cent, and we don���t propose to allow them to do so now.���

A day later, he interviewed Ann Eliza Young. During the long session, he asked the 30-year-old woman why she thought Young had acquired so many wives.

���Well, we (meaning she and the other wives) think it���s vanity. He just wants to show that if he is an old man he can marry young women; and he isn���t the only one in power who does the same thing.���

About a third of the dispatches are devoted to the divorce and other Mormon issues, apparently to feed the growing American fascination with the polygamous desert sect. The remaining articles are mostly sketches of the colorful characters that Cummings met on his curious journey to San Francisco. In one, he describes a winter storm from the point of view of a rancher along Gypsum Creek in central Kansas:

���A night���s ride in a hard norther, fifty vain endeavors to get the cattle turned against the wind, and then daylight. You find you are on the banks of the Arkansas River, and have lost some twenty or thirty animals. You are cold, frost bitten, hungry, and want to sit down and die. That is Kansas winter.���

Before Cummings left San Francisco on Nov. 4, 1873, he wrote the article that would appear in The San Francisco Chronicle announcing his departure. In it, he describes himself as ���an accomplished angler as well as a brilliant and vivacious writer.���

While Cummings makes a modern journalist uncomfortable with his megalomania and casual grip on the truth, his contribution to reporting ��� and to history ��� is undeniable. Milanich has rightly restored Cummings to public consumption. He plans a follow-up volume, one dealing with Cummings and his connection to Thomas Edison ��� it was Cummings, through his pieces in The New York Sun, that first brought the inventor to national attention, when Edison was searching for a suitably durable filament during the invention of the light bulb.[image error]

Published on October 26, 2009 09:15

October 25, 2009

Writing Western Noir

At 2:30 p.m. Sunday, Nov. 1, I'll be speaking at the Alford Branch Library in Wichita. My topic is "Writing Western Noir" and I'll tell the wicked but true story of how I went from Front Page Detective to HELLFIRE CANYON -- and won the Spur and a Kansas Notable Book Award along the way. The program is part of Western Days at the Wichita Public Library system. My colleague Jim Hoy is also doing a presentation on Flint Hills Cowboys Nov. 16 at the Alford branch.

At 2:30 p.m. Sunday, Nov. 1, I'll be speaking at the Alford Branch Library in Wichita. My topic is "Writing Western Noir" and I'll tell the wicked but true story of how I went from Front Page Detective to HELLFIRE CANYON -- and won the Spur and a Kansas Notable Book Award along the way. The program is part of Western Days at the Wichita Public Library system. My colleague Jim Hoy is also doing a presentation on Flint Hills Cowboys Nov. 16 at the Alford branch.

Published on October 25, 2009 21:38