Samir Chopra's Blog, page 19

August 27, 2017

Hannah Arendt On Our Creations’ Independent Lives

In ‘Remarks to the American Society of Christian Ethics’ (Library of Congress MSS Box 70, p. 011828)¹, Hannah Arendt notes,

Each time you write something and send it out into the world and it becomes public, obviously everybody is free to do with it what he pleases, and this is as it should be. I do not have any quarrel with this. You should not try to hold your hand now on whatever may happen to what you have been thinking for yourself. You should rather try to learn from what other people do with it.

In a post responding to David Simon‘s complaints about viewer’s ‘misinterpretations’ of his The Wire, I had written:

[T]here is something rather quaint and old-fashioned in the suggestion that viewers are getting it wrong, that they misconceived the show, that there is, so to speak, some sort of gap between their understanding and take on the show and the meaning that Simon intended, and that this is a crucial lacunae….once the show was made and released, any kind of control [Simon] might have exerted over its meaning was gone. The show doesn’t exist in some autonomous region of meaning that Simon controls access to; it is in a place where its meaning is constructed actively by its spectators and in many ways by the larger world that it is embedded in.

Arendt’s remarks obviously apply to the business of interpreting artistic works–just like they do to other creations of the human mind like philosophical theories of politics and morality. Once ‘made,’ once theorized, and sent ‘out there,’ they have a life of their own, now subject to the hermeneutical sensibilities and strategies of those who come into contact with them; these encounters are mediated by the interests and inclinations and prejudices of the work’s interpreters (as Gadamer would have noted), by the history of the world that has intervened in the period between the creation of the work and its reception by others. To attempt to reclaim the work, to insist on the primacy of the creator’s vision at the cost of others, to regulate how the work may be thought of and more ambitiously, modified to produce derivative works–these are acts of hubris, of vainglory. The openness of such works to a series of rebirths and reinvigorations prepares it for its encounter with greatness; its ability to entertain multiple ‘readings,’ to provide room for fertile exploration with every new generation, these mark a work out as a ‘classic’ one; indeed, such fecundity in the face of repeated exegesis is perhaps the most enduring condition of the ‘classic.’

Arendt’s remarks are cited by Margaret Conovan in her ‘Introduction’ in Arendt’s The Human Condition (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1998, p. xx) as he claims that this difficult but rich work will continue to endure precisely because it affords its readers so much opportunity for their own idiosyncratic encounters with the text and its theses. My discussions with my students this semester–as we read Arendt’s book together–will, I think, bolster Conovan’s assertions.

August 26, 2017

Acknowledging Reported Emotions Before ‘Explaining’ Them

Suppose you say, “I’m because of X .” As an example, “I”m sad because my brother ignored my birthday this year.” Now, suppose your respondent immediately launches into an ‘explanation’ of, or ‘apologia’ for, X: your brother didn’t really ignore your birthday, it’s just that he was traveling and didn’t have WiFi, and so wasn’t able to call you on the day. Or something like that. This response by your interlocutor attempts to fit the actions or events that have caused you some measure of emotional pain into some causal arrangement that makes your acquaintances’ behavior more explicable; it makes the case that the action was not personally directed, that it was not malevolent, and so on. Your interlocutors are attempting to defuse and remove the sting of the hurt; they are attempting a therapeutic maneuver, devising a narrative that will allow you–as if in the clinic–to tell a story that ‘works better’ for you.

This, more often than not, turns out to be a mistake; such ‘explanations’ and attempts to ‘mitigate’ the hurt, the anger, the pain, simply do not work; you remain as angry, perplexed, or irate as before; indeed, these emotions might have been exacerbated, and you might have an entirely new conflict, one with your interlocutor, on your hands. The problem, of course, is that the original statement has been misinterpreted; it is a confusion to think these statements are attempts to assign causal blame; rather, they are reports of feelings. When the person we are talking to starts to address the causal relationship they think they have detected, they have moved on past the original emotions that actually prompted the report. Contextualizing the reported emotion so that it fits into a wider nexus of actions and reactions and emotions is a worthwhile task; it may indeed make the sufferer feel they are not being persecuted, that they are not alone, and so on. But this sort of amelioration is best carried out after an acknowledgment of the feelings at play. These sorts of reports are calls for help; they report discomfort; they seek relief. But like any good healer, we must first make note of the symptom reported and only then attempt a diagnosis. To begin by offering apologia is a surefire method of negating and dismissing the initial report, which seeks, first and foremost, a hearing.

This kind of interaction is exceedingly common; I have participated in many myself, both as offender and victim. It is often reported as the kind of conversational play between men and women that sets the two genders apart distinctively i.e., men jump to ‘solving the problem presented’ while women ‘process the emotions reported’ (though I think gender lines cannot be so clearly drawn here; there are exceptions aplenty on both sides.) It derails more conversations than might be imagined; and it only needs the simplest of conversational maneuvers, an acknowledgment that we have been listening, to ameliorate it.

August 25, 2017

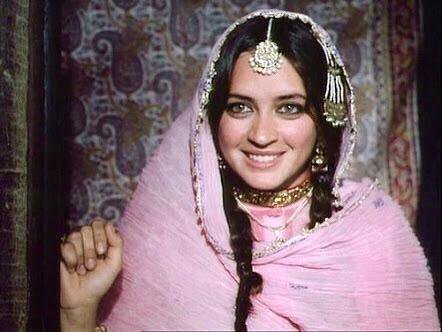

Childhood Crushes – I: Nafisa Ali In ‘Junoon’

I was eleven years old when I saw Nafisa Ali, then all of eighteen years old, play the part of Ruth Labadoor in Shyam Benegal‘s 1978 art-house classic Junoon–Ruth is a young Englishwoman, living on an English military cantonment in colonial India with her family. As the Indian Mutiny of 1857 breaks out, Ruth’s family is attacked in the church by rebels; her mother, grandmother, and her find shelter, first with a loyalist to the English, and then, later with a Pathan obsessed with Ruth, who wants to marry her and make her his wife. He does not succeed; Ruth’s fate is cleverly tied to the fate of the Mutiny by her mother; when the Mutiny fails, so does Javed Khan’s ‘claims’ on Ruth. But Ruth has–despite her early fear of the ‘mad Pathan’–fallen in love with the man who has pursued her and confessed to his obsessions; in the movie’s final scene at a church where Ruth and her mother are hiding, and where Javed has come to find them, as Javed prepares to ride off into battle to face the rampaging and revengeful English troops, Ruth rushes out to see Javed despite her mother’s disapproval, and blurts out a single word, “Javed!” Their eyes meet; their hearts have too. Then fade to black, as the movie’s epigraph informs us that Javed died in battle while Ruth died fifty-five years later in London. Unwed.

Nafisa Ali in Junoon:

I walked out of the theater that night, heartsick and crushed. I had fallen in love with Nafisa Ali. Madly, heartbreakingly so. It was the crush to end all crushes. Over the next few months, I wondered if even the fictional Javed Khan’s obsession could rival mine. Nafisa was drop-dead gorgeous; she was stunningly beautiful, a sportswoman, India’s national swimming champion, a long-legged beauty who had been cast in this art-house movie, thanks to her family’s connections in India’s film industry. She was only seven years older than me, a fact that somehow made her more real; she could have been that girl in the twelfth grade that I had a crush on (and I had had a few desperate ones already.) That movie’s final scene completed the legend of Ruth Labadoor for me; I had come to believe that such a girl had actually existed, that she had actually been love-lorn, and had indeed, died alone, of a broken heart, pining over a love that could not dare speak its name. That magical blending of reality and artifice, whereby I had come to believe that a fictional character had actually walked the earth was complete, made so by my adolescent pining for a beautiful young woman; on screen, she was vulnerable, heartachingly so, and I longed to somehow comfort her, to reach out and hold her hand, and tell her it was going to be OK. And ask her out for a movie, of course.

I went looking for Nafisa; I found her in the odd magazine or two, but nowhere else. She made one movie, and then little else; she faded from public life, and then, stunningly she was married, to an older man, an Army officer. All was ashes. My crush faded, like all crushes do. But I never forgot the phenomenology of that heartache she induced in me.

PS: Nafisa went on to act in a few movies, but never made a career in Bollywood; she is now a social activist in India. And she is still stunningly beautiful:

August 24, 2017

Lionel Trilling As Philosopher Of Culture

In Freud and The Crisis of our Culture, Lionel Trilling writes:

The idea of culture, in the modern sense of the word, is a relatively new idea. It represents a way of thinking about our life in society which developed concomitantly with certain ways of conceiving the self. Indeed, our modern idea of culture may be thought of as a new sort of self-hood bestowed upon the whole of society….Society in this new selfhood, is thought of as having a certain organic unity, an autonomous character and personality which it expresses in everything it does; it is conceived to have a style, which is manifest not only in its unconscious, intentional activities, in its architecture, its philosophy, and so on, but also in its unconscious activities, in its unexpressed assumptions–the unconscious of society may be said to have been imagined before the unconscious of the individual….Generally speaking, the word “culture” is used in an honorific sense. When we look at a people in the degree of abstraction which the idea of culture implies, we cannot but be touched and impressed by what we see, we cannot help being awed by something mysterious at work, some creative power which seems to transcend any particular act or habit or quality that may not be observed. To make a coherent life, to confront the terrors of the inner and outer world, to establish the ritual and art, the pieties and duties which make possible the life of the group and the individual–these are culture and to contemplate these efforts of culture is inevitably moving.

Trilling here offers two understandings of ‘culture’: first, in a manner similar to Nietzsche’s, he suggests it is a kind of society-wide style, a characteristic and distinctive and particular way of being which permeates its visible and invisible, tangible and intangible components; we should expect this to be only comprehensible in a synoptic fashion, one not analyzable necessarily into its constituent components. Second, Trilling suggests ‘culture’ is even more abstract, a kind of plurality of thing and feeling and sensibility that organizes the individual and society alike into a coherent whole. (This union can, of course, be the subject of vigorous critique as well c.f. Freud in Civilization and its Discontents.) This plural understanding of Trilling’s is a notable one: many activities that we would consider acts of self-knowledge and construction are found here, thus suggesting culture is a personal matter too, that the selves of many contribute to the societal selfhood spoken of earlier. Here in culture too, we find the most primeval strivings to master the fears and uncertainties of our minds and the world; religion and poetry and philosophy are rightly described as cultural strivings. Ultimately, culture is affective; we do not remain unmoved by it, it exerts an emotional hold on us, thus binding ever more tightly that indissoluble bond of rationality and feeling that makes us all into unique ‘products’ of our ‘home’ cultures. When culture is ‘done’ with us, it provides us with habit and manner and a persona; it grants us identity.

August 22, 2017

The Trump-Republican Legacy: Institutional Capture And Degradation

There might be some disputation over whether the Donald Trump-Republican Party unholy alliance is politically effective in terms of the consolidation of executive power or actual legislative activity–seasoned political observers consider the Trump administration to have been an utter failure on both fronts–but there can be little doubt about the extent of the damage the combination of the Trump administration and the Republican Party have done to American political institutions. They have done so in two ways: first, they have systematically captured components of the electoral and legislative process, exploiting their structural weaknesses and their dependence on good-willed political actors (which the Republicans most certainly aren’t); second, they have engaged in a wholesale rhetorical condemnation and ridicule of central and peripheral political institutions like the judiciary and the press.

In the former domain, we find a bag of dirty tricks that includes gerrymandering of state electoral districts, wholly fraudulent investigations into voter fraud, repression of voter registration, filibusters, supermajority requirements to call bills to vote on the floor, the stunning refusal to vote on a Supreme Court nominee following the death of Antonin Scalia, and so on. In the latter domain, we find the ceaseless vilification of judges who do not align their votes in the ideological dimensions preferred by Trump, an utter disregard for all manner of ethical proprieties (c.f. the absence of any sensitivity to the non-stop conflicts of interest that are this administration’s trademark political maneuver), and a wholesale rejection of any standards of truth or evidence in the making of substantive factual political claims.

The American polity will be rid of the Trump administration via resignation or electoral rejection soon enough; perhaps it will even remove the Republican Party from power from all three branches of government. It will not, however, be rid of the damage caused to its political institutions any time soon; it will take a long time to for this damnable stain to be removed, if at all. Cynicism about political institutions and practices is as American as various species of fruit pies; it is the natural result of a systematic effort by the political class to bring about widespread disengagement with national and state-level political processes, thus clearing the field for those seeking greater control over them. That effort has been spectacularly successful over the years; low voter turnout is its most visible indicator. The efforts of this administration and the Republican Party, aided and abetted, it must be said, by the Democratic Party, have pushed that cynicism still further, into realms where the abdication of political responsibility and the loud proclamation of moral bankruptcy has come to seem a political and intellectual virtue. So overt has the abuse of the political system been that a collective weariness with politics has prompted an ongoing and continuing abandonment of the field; better to walk away from this cesspool than to risk further contamination. That abandonment clears the way for further capture and degradation, of course; precisely the effect intended (see above.)

August 20, 2017

The Indifferent ‘Pain Of The World’

In All the Pretty Horses (Vintage International, New York, 1993, pp. 256-257), Cormac McCarthy writes:

He imagined the pain of the world to be like some formless parasitic being seeking out the warmth of human souls wherein to incubate and he thought he knew what made one liable to its visitations. What he had not known was that it was mindless and so had no way to know the limits of those souls and what he feared was that there might be no limits.

The ‘pain of the world’–its irreducible melancholia and absurdity, its indifference to our fortunes and loves and fears–can indeed feel like a malevolent being, a beast of a kind, one that may, if provoked, swat us about with a terrible malignity. Here, in these impressions, we find archaic traces of an older imagination of ours; the formless fears of the child’s world have congealed into a seemingly solid mass, serving now as foundations for our anxious adult being. It is unsurprising that we have found ways to pay obeisance to this beast through prayer and fervent wishing and day dreaming and fantasy and incantations and magic and potions; we hope to pass unnoticed through its gauntlet, afraid to set astir the slumbering beast and provoke its attentions and wrath. As John Grady Cole, McCarthy’s character, notes, we fear two things especially about this beast: we suspect ourselves to be particularly vulnerable to its depredations, a particularly attractive prey for this predator; we fear we sport a bull’s eye on our backs, a scarlet letter that marks us out as an offender to be dealt with harshly; we fear there may be no limits to its appetites; we sense that lightning might strike not once, not twice, but without no constraint whatsoever; perhaps we ain’t seen nothin’ yet, and much more misfortune awaits us around the corner on life’s roads.

In our darkest moments we attribute a malevolent intelligence to this beast, but we know the worst eventuality of all would be a mindless beast, one whose ignorance of us and our capacity to tolerate pain could cause us to plumb unimaginable depths, to experience pain whose qualities defy description. (The fears of these sorts of mental chasms are expressed quite beautifully in Gerard Manley Hopkins’ mournful poem ‘No worst, there is none. Pitched past pitch of grief.’) McCarthy also seems to suggest the possibility of a presumption of ‘too much’ knowledge on Cole’s part–a la Oedipus, a possible arrogant claim to know the ways and means and methods and mind of the beast; but as McCarthy goes on to note, there is no mind here to be known, no rationale to be assessed, no strategy or tactic to be evaluated; there is merely being and man, caught up in its becoming. It is this irrelevance of man and his capacities and attributes to the working of this beast which is Cole’s deepest fear; it is ours too, the root and ground of the absurdist existentialist vision.

August 19, 2017

On Being In A Quandary On Quandary Peak

On July 19th, my wife, my daughter (aged four and a half years), and I set off to hike Quandary Peak in Colorado–one of the state’s fifty-three fourteeners. We awoke at four a.m., left at five a.m. and after a longer-than-expected drive, were on the trail at 7:50AM. By Colorado standards this was a tad bit late for hiking a 14’er; the truly wise depart the trailhead a little after six so that they can be safely off the mountain in case of an afternoon thunderstorm–a very common occurrence in the Rockies. The hike up to Quandary’s summit is considered an ‘easy’ one by 14’er standards; there are no scrambles, no technical climbing is required, just a hike up to the top.

But that hike still requires you to gain some three thousand feet of elevation in a little over three miles, which can be a reasonably sized task if you are: a) not used to the altitude; b) a young human being with short legs. Both these conditions were true of my daughter, so our progress up the trail, and especially on Quandary’s East Ridge which offers a rocky path over talus, was markedly slower than the other folks heading on up. On several occasions, as my daughter complained of tiredness, and as I glanced up at the imposing East Ridge, I wondered if our plan to hike the mountain was truly practical. At about noon or so, we ran into some acquaintances heading down after having reached the summit. We stopped to chat; their closing remarks were, “You’ve got glorious weather today even if you’re a bit late!”

Famous last words.

We finally made it to the summit around 1:30 PM. Between 1 and 1:30 dark clouds rolled in as we ascended the final few steps to the summit; I reached first, my wife and daughter followed. My heart sank as we ate a hasty lunch; we were late, and our fortunes had changed for the worse, all too quickly. A storm was brewing, and we needed to get down, off the ridge, down among the trees, quickly. Thunder and lightning were threatening and an exposed ridge was no place to be.

Unfortunately, and entirely expectedly, our descent down the ridge was tediously slow; my daughter was exhausted and spent; her mood had changed for the worse. Getting her down a rocky trail with big steps was hard work; it was made harder by the rain and by a whipping wind that chilled us quickly. Up and around us, thunder rumbled, and lightning flashed. We continued on down, slowly, nervously, trying to keep our daughter’s spirits up as best as we could. She was not shivering, but did complain about the cold; we quickly threw on all the layers we had on her and continued walking. A bearded hiker walking down past us issued a chilling warning; he had noticed my wife’s hair standing up on end, a sign of static electricity in the air, and advised us to throw away our hiking poles if we heard a buzzing sound ‘like bees’–a warning of an impending lightning strike. We hurried on as best as we could through the intermittent sharp rain and wind, casting longing glances at the pine trees and sundry bushes below at treeline. At 5:30 PM, I started to wonder if we would be able to get to the trailhead before it turned dark; our place was glacial and daylight was not unlimited.

Finally, once we made it to the treeline and as the weather improved, and temperatures rose, our pace quickened, and my daughter’s mood improved. She became receptive to humor again, and we even indulged in some horseplay as we approached the trailhead. We made it to our car at 6:30PM, damp and bedraggled and exhausted. But safe. A hot meal in Frisco restored our mood; my daughter dozed off in the restaurant, and only awoke once we had reached ‘home’ in Louisville.

We made several miscalculations: a) we should have done a ‘warm-up’ hike to ease into the rigors of this ascent, especially because we were hiking with my daughter, who has hiked a bit before but would have still found the learning curve steep on a hike that involved three thousand feet elevation gain; b) we should have found a way to start earlier; c) we should have made a snap decision sometime between 1 and 1:30 PM to have turned back–we were definitely guilty of a little ‘summit fever,’ perhaps understandable for we were very close to the summit when the bad weather did show up.

Still, in the end, like all ‘good’ adventures, the hard times ended safely, and we had a stock of stories for the future. And my daughter has bragging rights to her first 14’er.

August 17, 2017

The Republicans Will Ride Out This Latest ‘He Can’t Survive This’ Moment

As usual, anxious liberals and American citizens all over the nation are waiting, with bated breath and a dollop of some old-fashioned American optimism, for the Great Abandonment: that crystalline moment when the Republican Party will decide that enough is enough, issue a condemnation–with teeth–of Donald Trump, begin scurrying away from his sinking ship, and for good measure, initiate impeachment proceedings. There’s been many moments like this: grab-their-pussy and the various bits of La Affaire Russia have served to provide the best examples of these in the recent past. Neo-Nazis in Charlottesville, and their usual brand of toxic racism and violence have now provided the latest instance of a possible ‘he can’t survive this’ moment–‘this is when the Republicans grow a vertebra, denounce Nazism–oh, how difficult!–and its sympathizers and enablers, and bring this particular Trump Tower crashing down.

Unfortunately this Godot-ish vigil will have to persist a little longer. Perhaps till the end of the Trump presidency. Condemnation of the President has been issued by some: Mitt Romney and Marco Rubio for instance. But there is no party-level move to censure; there is no sign that there is widespread movement among the Republicans to either distance themselves from Trump or do anything more than issue the easiest political statement of all regarding disapproval for Nazis.

The electoral calculus, the bottom-line politically, is that Republican voters care little about Trump’s being in bed with white supremacists, the KKK, and sundry other deplorables; they elected him to assuage their racial anxieties, and he continues to do that by standing up even for cross-burning, swastika tattooed, hooded folk. A Republican Congressman or Senator who denounces Trump risks electoral suicide; the Trump ‘base’ will turn on him or her with indecent haste. Under the circumstances, far better to issue generic denouncements and move on, hoping and knowing this storm will blow over. When private business corporations dump offensive employees–perhaps for racist, abusive speech or other kinds of socially offensive behavior–they do so on the basis of a calculus that determines the nature and extent of the economic loss they will have to bear if they persist in supporting their offending employee; when it is apparent that customers will not tolerate that behavior, the decision is made for the employer. That same calculus in the case of Republican voters suggests there is no loss forthcoming–the strategy suggested is precisely the one on display: a little bluster, a little obfuscation, some hemming and hawing, a few offensive suggestions that the offensive behavior was in response to other behavior ‘asking for it’ and so on. Still riding on S. S. Donald Trump, sailing right on over the edge to the depths below–even as the merry band of carpetbaggers on board keep their hands in the national till.

I’ve made this point before on this blog (here; here; here; here); I repeat myself. Repetition is neurotic; I should cease and desist. But it is not easy when neurotic repetition is visible elsewhere–in this case, in the American polity.

August 16, 2017

Toppling Confederate Statues Does Not ‘Erase’ The Confederacy From ‘History’

News from Baltimore and Durham suggests a long-overdue of cleaning American towns and cities of various pieces of masonry known as ‘Confederate statues’; young folks have apparently taken it upon themselves to go ahead and tear down these statues which pay homage to those who were handed a rather spectacular defeat in the American Civil War. News of these evictions has been greeted with a familiar chorus of pearl-clutching, teeth-gnashing, and chest-beating: that such acts ‘erase history’ and contribute to an unwillingness to ‘move on,’ ‘let go,’ or otherwise ‘move on,’ all the while keeping our eyes firmly fixed on the rearview mirror, bowing and scraping our heads to those who laid their arms on the ground and accepted unconditional terms of surrender. This offence against memory and history should not be allowed to stand; but those statues sure should be. It’s the way we get to be are truly grown up, mature, adult Americans.

This is an idiotic argument from start to finish; no amendment will redeem it.

Toppling the statues of Confederate leaders–the ones who prosecuted and fought the Civil War on the wrong side, who stood up for a racist regime that enslaved, tortured, and killed African-Americans–does not erase those leaders from American history; it merely grants them their rightful place in it. The stories of John C. Calhoun and Robert E. Lee–to name just two worthies whose names have been in name-changing and statue-toppling news recently–will continue to live on in history books, television documentaries, biographies, movies, Civil War reenactments, autobiographies, and battlefield monuments. Generations of American schoolchildren will continue to learn that the former was a segregationist, a racist, an ideologue; they will learn that the latter, a ‘noble Virginian,’ was a traitor who fought, not for the national army that granted him his station and rank, but for his own ‘home state,’ a slave-owning one. The toppling of their statues will not prevent their stories being told, their faults and strengths being documented.

What the toppling of their statues will achieve is bring closer the day when these men will no longer be treated as heroes of any kind, tragic or otherwise. The toppling of statues will make it harder for young schoolchildren in the South and elsewhere to think that those memorials in their town serve to recognize courage or praiseworthy moral principles; it will prevent racists in the US from using them as rallying points, as faux mementos of a faux glorious past.

History is far more capacious than the defenders of the Confederacy might imagine; it holds many stories all at once, and it lets us sort them a;; out. The defenders of the Confederacy are not afraid that their heroes will be erased from history; they are afraid that a history which has no room for their statues will have considerably increased room for alternative historical accounts of the men who were once so commemorated.

Let’s take out the trash and replace the statues of racists with statues, instead, of those who fought to emancipate the slaves–in any way–and to erase the terrible blot of slavery from America.

August 15, 2017

Thirty Years After: Reflections On Migration

Thirty years ago on this day, I migrated to the US. At New Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport, I boarded a British Airlines flight to London Heathrow from where I would board a connection to New York City, and set off. My mother and my best friend dropped me off at the airport; my grandmother had bought me a one-way ticket with her savings as a farewell gift. I ran to the gates; I was eager to leave, eager to move on to a new life. Thirty years later, in at least one measure, I haven’t gone too far; I’ve only moved from John F. Kennedy International Airport to Brooklyn in New York City; I’ve remained stuck on the East Coast, only able to make a short hop across the Hudson River from New Jersey to New York City–with a short, two-year stint in between in Sydney, Australia. But much–besides the progression of visas and residency permits from F-1 to H-1 to ‘green card’ to ‘US passport’–has changed.

Then, I was twenty; now, I’m fifty. Then, I was single, about to commence a graduate program in computer science and go on, hopefully, to a ‘respectable’ job. Now, I’m a husband and a father, a professor of philosophy at one of America’s largest urban public universities. Then, I would speak of a ‘home’ left behind; now, I can only write ‘home’ in scare quotes, even as I acknowledge that I have found one on this side of the world, one in which my daughter will grow up and find her way about, one whose well-being and future concerns me more than other places elsewhere; it is the place in the world to which I’m the most committed, emotionally and politically.

I’m a mongrel now; I sound funny to both Indians and Americans because my accent has morphed; both ‘sides’ have accused me, on occasion, of being insufficiently ‘genuine,’ of not being ‘the real thing’; immigrants can never be the McCoy; we will always be ‘outsiders’ no matter where we go; more than one group can tell us to ‘go back where we came from.’ Back in India, I feel like a tourist who can speak the local language really well; that land too has changed while I was ‘away.’ My in-laws live in the US; my daughter will find grandparents only here. She will know little of India and where ‘I came from’; she will not speak an Indian language. Children are always strangers to their parents (and vice-versa); the children of immigrants perhaps even more so.

In an essay I wrote recently, I made note of my aspiration at one time to be an ‘American immigrant’–it was a description that spoke of both success and a virtuous kind of work, one that elevated the very being of those who undertook it; it was how I understood the American immigrant experience from afar. Like all things observed from a distance, many of its most crucial features became visible on closer inspection; the life I was to undertake in the US would be considerably different from what I had imagined it to be. I was often found wanting; as was, it seemed, my home of choice. I considered myself prepared for this new life; I was not. But those shortfalls, those gaps, those mismeasures, they all added up to a new understanding of myself and this place. ‘America’ and ‘I’ both acquired new contours thanks to this encounter of ours. America acted on me, and I on it; it was bound to be an asymmetrical relationship; I changed more than America did in response to my presence here. But I like to think I’ve made this little patch of mine distinctive too, and brought to it my own peculiar and particular stamp, my own unique influence and signature. My childhood in India colored my sense of time and space and still influences the way I see the world; but America, and its landscapes and light and air and skies have crept into my being too; they too, now, afford me the lenses with which I sense and experience the world.

In these three decades past, I learned, in America, all over again, that I was not and could not be, a self-made man; that I would always rely on the aid and succor provided by others. Sometimes they were other immigrants; sometimes they were Americans, of all stripes, kinds, and colors. They all helped me, all loaned a helping hand. Some loaned me money, others bought and cooked me meals, gave me a place to sleep, told me where to go, what to do, spoke up for me, taught me, loaned me books, read my writings–this list could go on. I’m not a self-made man; I’ve relied, unashamedly, on others, on friends, family, and strangers. An immigrant’s story can never just be about the immigrant; it must also be about all those who made that life possible. I’m glad that others have helped write the book of my life; and I’m glad that so much of it has been written in America, by Americans.

My political stance often casts me as hyper-critical; it is an anxious one, eager to make this land into a better one for my family and my friends and for the communities that have given me a home over the years in this land. My concerns for my former homeland are far more limited; my political ambit is circumscribed by my location and my available commitment; I have become an American by dint of where I live, and what I care about the most.

I have not stopped moving yet; I sense more displacement in my future. I am reconciled to it; it seems like a way of being. Indeed, I feel restless now, astir again. Migration induces a restlessness that will not cease; the initial inertia of our first home is never regained. I used to bemoan the lack of a resting place; now, I could not abide the absence of motion, possible or actual. Other migrations might lie yet in my future.