Robin R. Cutler's Blog, page 5

July 25, 2016

Such Mad Fun Prologue — All the Things You Were

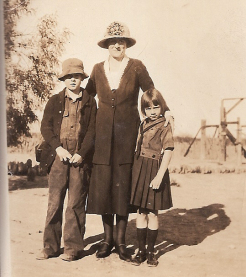

Daysie Hall with Dick Wick Hall Jr. (Dickie) and Jane in Salome 1925.

I picked up the book carefully, wary of the mold on its faded cover. Rodents had gnawed through the corners and the edges of its pages. On this oppressive June day when the humidity intensified all sweet and sour odors, the book smelled terrible. It was headed for the landfill, but the playful inscription to Jane Hall and the bold signature on the front endpaper caught my attention: F. Scott (“Pretty Boy”) Fitzgerald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer 1938.

My mother was twenty-three when Fitzgerald brought her this copy of Tender is the Night. She’d been an art student and aspiring author on its publication date in 1934. Three years later, the snappy dialogue in her short stories caught the interest of celebrated Hollywood agent, H. N. (“Swanie”) Swanson; within a few months she was hard at work at MGM. Before long, Jane Elizabeth Hall and F. Scott Fitzgerald were colleagues in adjoining offices at Hollywood’s most successful studio.

I carefully tore out the page with the inscription and filed it with other papers that seemed to be worth keeping for another day. It was 1987 and Jane, as I will call her in this book, had died on April 18, the Saturday before Easter. I had tried to telephone her on that brilliant April morning to let her know when we would arrive at Poplar Springs. After the fourth attempt I began to panic; she always answered the phone. But she was there, lying peacefully on her double bed, her hands clasped on her chest, surrounded by books, papers, half empty boxes of Milk Bone dog biscuits, a small television on the bureau that was always on, and eleven anxious German shepherds trying to wake her up. Her loaded .38 revolver— a gift from the local sheriff because she was so alone in that sprawling stone manor house out in the Fauquier County countryside—was still in the nightstand drawer.

Until a heart attack ended her life, Jane had a special cachet in Virginia as a former Cosmopolitan cover girl who had worked in Culver City for Louis B. Mayer. Jane married during her years as a screenwriter, and I had no idea that she had known Fitzgerald. Though she rarely spoke about her career, a few weeks before she died, she mentioned to me that she’d had a chance at real happiness between 1935 and 1942, when she’d been productive as an author. For so much of my life, she’d seemed preoccupied by money worries and swamped with business problems; in her later years she struggled with physical pain from a back injury. I wanted to learn more about the days when her green eyes sparkled, she laughed often, and her wit was razor sharp. What was it like to work as a writer in Hollywood? How did she end up there? Why did she leave? I didn’t expect to postpone my search for the answers to these questions for twenty-two years.

On a chilly October morning in 2009, I began, finally, to look through my mother’s papers that I’d kept in storage for so long. As a historian, I naturally focused on the years before I was born. As I pored through a scrapbook filled with poems, stories, articles, editorials, and book reviews that she’d published before she was fifteen years old, my heart went out to the young tomboy from an Arizona mining town who wanted passionately to be a novelist. Often she’d described people on the fringe of life — an elderly lady ignored by a bus driver; the son of a laundress spurned by a pretty wealthy girl; a lonely street sweeper at midnight; or an alcoholic confined to a hospital bed. Her hard work was driven in part by the premature death of her father and idol, Dick Wick Hall, then Arizona’s favorite humorist. Jane’s fierce ambition and success as a juvenile author led the press to call her a “literary prodigy.” But her determination would be diluted for a time after her mother succumbed to breast cancer in 1930.

Once she became an orphan, Jane’s circumstances — and, therefore, the subjects she wrote about — changed dramatically. She and her brother traveled east to live with an aunt and uncle as part of a rarefied segment of Manhattan and Virginia society. Jane brought an outsider’s perspective to her new life among the debutantes and party girls of the Depression years. And she used what she learned to portray and parody this privileged world in her fiction and screenplays. Her diaries and scores of letters provide an appealing look at what it was like be a “womanwriter” in Depression America. Her voice is candid, refreshing, and at times disturbing as she describes her response to the demands of editors, producers, studio executives, and the watchdog of the production code administration, Joseph Breen. Her published stories, articles, and screenplays depict an absorbing if narrow slice of popular culture in New York City and Hollywood during the turbulent 1930s.

At MGM Jane’s days “belonged only to Louis B. Mayer.” She worked long hours for some of his top producers dreaming up scenarios and clever dialogue that drew on her experiences in Manhattan. In August 1939, eight months after Cosmopolitan published her “book length novel,” These Glamour Girls, the movie of the same name premiered in New York City. The trailer announced “Jane Hall’s blistering expose” of the “platinum-plated darlings of the smart set;” The New York Times called it the “best college comedy” and the “best social comedy of the year.”

Jane not only wrote stories and screenplays, she reported from Culver City for Good Housekeeping and Cosmopolitan. Her editors there (William Bigelow and Harry Burton) loved the way her buoyant personality came through in her lighthearted interviews with MGM celebrities, and in her account of her visits to the sets of The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind. Her letters home reveal the fun she had lunching with Rosalind Russell, dining with Walter Pidgeon, dancing with Jimmy Stewart and sailing to Catalina on Joe Mankiewicz’s schooner.

I became intrigued by the way Jane participated in and observed the “culture of elegance” that magazine readers and movie audiences yearned for during the Depression. Historian Morris Dickstein finds that “a culture’s forms of escape, if they can be called escape, are as significant and revealing as its social criticism.” The 1930s, a decade often defined by the suffering and poverty that decimated millions of lives, was also “rich in the production of popular fantasy and trenchant social criticism.” Jane’s storytelling, laced with insight and satire, is a window into a world that was inaccessible to most Americans then and remains so today.

What determines who a woman will become? It was only after she died that I discovered the album of photos from my mother’s childhood. In one image a tall, proud woman stands with her arms around her two children in the brilliant sun near Salome, a hardscrabble mining town in western Arizona.

The woman, Daysie Sutton Hall, is the grandmother I never met. On her right is thirteen-year-old Dickie, Jane’s brother, in scruffy overalls and an oversized sweater, a cloth fedora pulled down low to shade his eyes. The ten year old girl on Daysie’s left wears a pleated skirt and middy, scuffed shoes, and knee socks pulled up tight. The light brown bangs of her cropped hair almost reach her eyebrows. It is the girl’s “don’t-mess-with-me” expression that stands out in this 1925 sepia photograph. For she is fearless, funny, mischievous, and proud to be a tomboy who can ride “Killer,” the wildest horse in the desert hamlet that her father cofounded. What thrills her most is that she has just had her first story accepted by the Los Angeles Times.

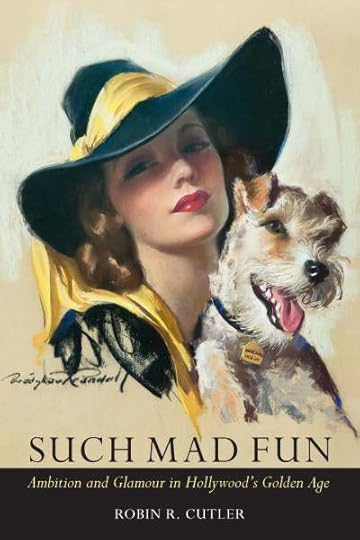

I grew up with a different image of Jane. The centerpiece of our living room was Bradshaw Crandell’s full-length portrait of Mrs. Robert Cutler (Jane’s married name). There she is a stunning platinum blonde in a long black velvet evening dress with a white ermine neckline. She appears to be a tall woman with a movie-star figure, perfect features, and ruby lips and nails. The large emerald that sparkles on her left hand matches her green eyes. The woman in this portrait is as inaccessible as classic-era stars in publicity photos. The black wool carpet and ivory upholstered furniture that defined the large paneled room complemented Crandell’s work. Many people loved the exquisite painting — movie stars and numerous prominent men and women sat for Crandell who, in 2006, was inducted posthumously into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame. But it reminds me of the P. D. Eastman book that I once read to my grandsons: Are You My Mother?

Such Mad Fun follows a talented small-town girl with grand ambitions who sought to be independent at a time when her family, her friends, and her social and cultural milieu had other expectations for her. It is also a behind-the-scenes look at the messages that popular culture conveys to its audiences. Feminist Betty Friedan underscores the critical role that magazines played between the 1930s and the 1950s in defining women’s sense of who they were meant to be. Who was the ideal young woman — more specifically the ideal young white, middle and upper-middle-class woman — targeted by so many magazines and movie houses? Whether for print or for the screen, Jane’s stories brim with class conflict while providing guidance for her peers on how to navigate in the eternal search for the perfect mate.

In the 1950s, my mother was often a mystery to me — if her bedroom was not off-limits, I headed straight for her mirrored dressing table just to look, not to touch, the artist’s tools that allowed her to transform herself into a glamour girl before she could be seen in public. She rarely came out of her room without her “face on”; I don’t recall ever seeing her with wet hair. I must have sensed that her life was not what she thought it should be. And after her death I wondered how the plucky tomboy in the photo album became the woman in Crandell’s portrait. What was lost and gained in the process? Something dramatic happens to little girls as they approach adolescence — many lose their voice. This book is both a coming-of-age story and a cautionary tale set in the cultural and social context of a decade that has surprising parallels with American life today.

Such Mad Fun is now available on Amazon and other sites for pre-order. The release date is September 8.

For additional images click here. For reviews click here.

Filed under: Such Mad Fun Tagged: "These Glamour Girls", 1930s, Arizona History, Bradshaw Crandell, Cosmopolitan Magazine 1930s, Dick Wick Hall, Good Housekeeping 1930s, Jane Hall, Louis B Mayer, MGM, popular culture

June 28, 2016

Chicken Soup for the Stars

Well the good news is Such Mad Fun is almost ready to launch. Thanks in part to the stellar team freelancing for View Tree Press, we received a starred Kirkus review a few days ago. And I’m so grateful for the encouragement of advance readers. So far only one typo has turned up, but then there’s this dilemma that every author dreads after a book has gone to press. Did I make a mistake by attributing the chicken soup recipe in MGM’s famous commissary to the wrong woman? Martin Turnbull, who knows more than most about what was really going on in Hollywood in the 1930s, pointed out that the chicken soup recipe that was so popular at MGM’s famous commissary came not from Louis B. Mayer’s wife, as I had written, but from his mother. Now that’s an error that needs attention.

Well the good news is Such Mad Fun is almost ready to launch. Thanks in part to the stellar team freelancing for View Tree Press, we received a starred Kirkus review a few days ago. And I’m so grateful for the encouragement of advance readers. So far only one typo has turned up, but then there’s this dilemma that every author dreads after a book has gone to press. Did I make a mistake by attributing the chicken soup recipe in MGM’s famous commissary to the wrong woman? Martin Turnbull, who knows more than most about what was really going on in Hollywood in the 1930s, pointed out that the chicken soup recipe that was so popular at MGM’s famous commissary came not from Louis B. Mayer’s wife, as I had written, but from his mother. Now that’s an error that needs attention.

I checked my sources and discovered that a terrific book, MGM: Hollywood’s Greatest Backlot, by Stephen Bingen, Steven X. Sylvester and Michael Troyan, has this to say: “believing that excellent, well-prepared food would keep his employees on the lot and avoid long lunch breaks, L. B. Mayer originally put his wife in charge here. Margaret Mayer trained the chef herself, supplying him with a recipe for her husband’s favorite chicken soup (‘take nine fat, two-year-old kosher hens for every three gallons of liquid, stewing them overnight, then separating the broth from the chicken. Add chunks of chicken and delicate matzoh balls’) for 35 cents a bowl.” This was great chicken soup, loaded with “‘big chunks of chicken and noodles,'” according to one lucky person who got to taste it. So was Martin right?

My other go-to person for everything in classic Hollywood is Scott Eyman, author of THE biography of Louis B. Mayer. Uh oh, Eyman’s book confirms that L. B.’s mother was the source of the recipe. Her name rarely comes up, but she was Sarah Meltzer Meir, and I’m sure she would like proper credit. Can’t you just imagine her fixing that soup for little Lazar and his two sisters in Minsk, and then eventually in Rhode Island where his brothers were born in 1888 and 1891.The pot no doubt got much bigger for this family of seven when they lived in St. John, New Brunswick, Canada. How great those matzoh balls must have tasted when Lazar came home after roaming the streets to collect scrap metal. (He left school at about the age of 12 to help support his family.)

Of course, Jane Hall knew nothing about this history when she used that chicken soup at MGM to soothe one of her frequent sore throats on a damp February afternoon in 1938. And as for the book, just in the nick of time, thanks to ever- patient designer Elliot Beard, I changed the reference to give Sarah credit. But maybe both sources are right. Margaret Mayer’s recipe may have come from her mother-in-law. If you have one of the advance copies, just enjoy the soup and don’t worry about the source.

Filed under: Such Mad Fun Tagged: 1930s Hollywood, Elliott Beard, Jane Hall, Louis B Mayer, Martin Turnbull, MGM, Sarah Meltzer Meir, Scott Eyman

May 6, 2016

“I want to be famous” — Jane Hall says farewell to her father’s mentor

Jane Hall and Margaret Gregory, New York Times, November 16, 1933.

It did not take Jane long to plunge right back into juggling school and her social life once she returned to Manhattan at the end of September 1933. At the newly coeducational Day Art School at Cooper Union (no longer called the Woman’s Art School), Jane signed up for Ornamental Modeling, Advanced Composition, Perspective, Advanced Design and, her favorite class, Life Drawing and Painting. She felt good about her second year—”I’m drawing much better, it seems to me, than I did last year. But I have to,” she told her diary. At least there were few distractions from boys at the day school– they all had jobs and continued to enroll in the Night Art School.

Jane would do her best work over the next two years in Life Drawing, taught by the well-known American regionalist painter, John Steuart Curry. A Kansas farm boy, Curry shared Jane’s love for animals and nature. After studying at the Art Institute of Chicago as well as in Paris, Curry worked as an illustrator for The Saturday Evening Post between 1921 and 1926, the years when Tom Masson saw to it that Dick Wick Hall’s stories were featured in the magazine. As her second year at Cooper Union began, Jane knew she should try extra hard in Mr. Curry’s class.

But once again, school did not have her undivided attention. The elaborate process of being introduced to Society enthralled Jane as she entered a world fueled by publicity and filled with spectacle. Between October 1933 and April 1934, Jane supplemented her diary with “an authentic and unexpurgated record of the haps and mishaps attendant on ‘Coming Out.'” This “Debutante’s Year Book” is the chronicle of a participant observer – a reporter and party girl who yearns to have her own story matter. It’s a tale of seduction by the temptations that are integral to a life of glamour – and of Jane’s reaction to the young men who, once she was “out,” competed mightily with her mission to become an artist or a writer or both. Jane did not write in the year book every day. Instead, she recounted a series of incidents, some of which would inspire her future stories and screenplays.

One of these memorable experiences occurred at the end of the last weekend of October 1933. She’d been the guest of Doug Frank and his parents in East Orange, New Jersey. They’d gone to the Rutgers-Lehigh football game (Rutgers won 27 to 0), and a party afterwards. On the way back to the city on Sunday afternoon, Jane stopped to see an ailing Thomas Masson and his wife, Fannie, at their home in Glen Ridge. The 66-year-old humorist and editor, now bedridden, was much smaller than she remembered. But she was touched that Masson agreed to see her because “I am my father’s daughter.”

The Massons, Jane reported, “had the Navajo rugs Daddy gave them on their sun porch. Masson and I were discussing Daddy’s temporary fame and his untimely death and he said, ‘so, it all goes back into Limbo. But that doesn’t matter.’ Well I think it does matter. I want to be famous and stay famous and have everybody and everybody’s great-grandchildren know I am and was famous.” Eighteen-year-old Jane knew this line of thought was presumptuous, but she didn’t care. She was still incensed by the fact that her Daddy’s life had been cut short just as he became well known.

Tom Masson died eight months after Jane’s visit. Her job over the next few years would be to channel her ambition and anger into deciding what she wanted to accomplish. In the fall of 1933, plenty of people would see her pictures in newspapers as a debutante; Jane knew what a laugh her father would have had over that way of getting attention. Still it was great fun at the time.

More fun starts soon! Such Mad Fun is about to be launched. The next post will have the details.

Questions or comments welcome through the Contact Tab. For more on Dick Wick Hall check out, The Laughing Desert.

Filed under: Such Mad Fun Tagged: 1930s debutante life, Cooper Union, Dick Wick Hall, Jane Hall, John Steuart Curry, Such Mad Fun, The Laughing Desert, Thomas Masson

March 30, 2016

Debutante Distractions in 1933

In light of all the current crises affecting Americans, who would believe that during the fall and winter season the tradition of holding debutante balls still continues in major cities? Yet look how many of us loved immersing in the pageantry of Downton Abbey. The practice of presenting marriageable daughters to eligible young men from prosperous families dates back to Babylonian times.* Though most modern young women find the deb scene old-fashioned and elitist, the privileged young ladies and their beaux who still participate in these elegant festivities become stars for a time; their pictures even appear in newspapers such as The New York Times. [They come from all over the world; check out the video here.]

In the depths of the Depression in 1930s Manhattan, debutantes were not only popular, they were a source of fascination to many people who struggled with a new grim economic reality. As it turned out, learning her way around this narrow social world would one day provide Jane Hall’s ticket to literary success.

Rose and Randolph Hicks were eager for Jane to marry well as their savings had been decimated by the Wall Street crash. It was clear that Jane was not likely to find a financially secure mate at her all-scholarship art school, The Cooper Union. So the Hickses teamed up with the parents of one of Jane’s former classmates, Margaret Gregory. “Muggy” and Jane would “come out” together in the fall 1933 season at a tea dances in New York and in Virginia.

When she heard the plans, Jane was thrilled. She’d had a “grand old time” that spring tempered only by the memories that haunted her on April 28 (the seventh anniversary of her father’s death), and on May 12 as she lit a candle for her late mother at St. Ignatius Loyola Catholic Church on Park Avenue. For the first time in her life she was popular with boys. But Jane saw her dates as pals; she took none of them seriously and that was dispiriting to those who fell hard for her. Nevertheless, on evenings and weekends, they all had plenty of fun. When they were not at parties, they danced to the sound of big bands, tried out restaurants in Greenwich Village and Coney Island, went to the theater, or drove around the city with the top down on snazzy convertibles. The most popular pastime was the movies, some of which (such as those starring Mae West), were quite risqué in the years before 1934 when the Hollywood Production Code was strictly enforced.

For some of Jane’s crowd the big news in early April was “Beer is back!” At least 3.2% beer was (though the legal age in New York was 21). Always wary of alcohol as her mother had been, Jane now acknowledged that Prohibition, which would not officially end until 5:32 p.m. on December 5, 1933, was an “asinine law.” Although Jane rarely tried alcohol, abstention was never the case with her dates. At a beer party at 535 Park Avenue, one of the boy’s fathers bet them five dollars each that “they couldn’t drink a soup plate of warm beer with a teaspoon. They all won.”

In the summer of 1933 there was much to look forward to. Jane on the terrace at Poplar Springs.

As Jane prepared to spend the summer in Virginia, having just made it through her first year of art school, she hoped she would be productive despite the many distractions of her new social life. Would this serious young author and artist who once had such strong career ambitions be seduced by the revelry that awaited her in the summer and fall of 1933? She recorded it all in her diary and in a “Debutante Yearbook” that she kept between October 1933 and April 1934.

*For a useful survey of this age-old tradition see Karal Ann Marling, Debutante: Rites and Regalia of American Debdom (2004).

Filed under: Such Mad Fun Tagged: Central Park 1933, debutantes history, debutantes of 1933, end of prohibition, Jane Hall, Randolph Hicks, Rose Sutton Hicks, social life and customs United States

March 13, 2016

An Artist or Writer or Both?

For decades Cooper Union had been directed by a Ladies Advisory Council, “whose members drove to the monthly meetings in early American Pierce-Arrows.”* In 1931, these prominent matrons decided to modernize the school. They found a new director, Austin Purves, Jr., who convinced the ladies of the value of coeducation – eventually 40% of the students would be men; he also got the go-ahead to let the male students work in their shirt sleeves. By the time Jane started her classes, students could also draw from nude models.

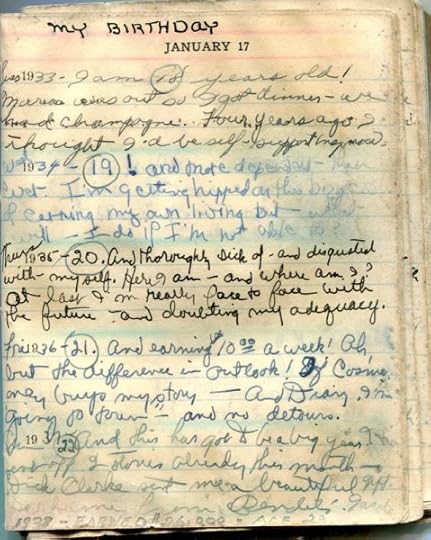

In her first year, Jane took free hand drawing, modeling (in clay), elementary design, composition and lettering. She loved Cooper in spite of the old building’s poor ventilation and the fact that she caught several nasty colds and pneumonia during the winter months. The school was open to everyone, regardless of race, creed or color, and her fellow students’ personalities and accents were a constant source of fascination. She kept a five-year diary between 1933 and 1937 that reveals how she struggled with teachers who expected a lot from their students. Jane grappled with whether or not she should be an artist or writer or both. When the going got tough, she also thought about being an actress as her Nightingale pals had predicted she would be. And all through these years her aunt and uncle worried about how their niece would support herself unless she married well.

Jane’s Birthday Page from the Five-Year-Diary (It was damaged in a fire in 1957.)

Five-year diaries are organized to encourage reflection. Each page for a day in the year is split into five one year sections with about four lines for a single day. At the end of each month is a memo page. On the January 1933 memo page Jane reminded herself: “When I get to the bottom of this page I certainly ought to be somewhere in art. I’ll be 22 years old.” Throughout the winter and spring of 1933 she was absorbed by working hard for Austin Purves. Clearly a hard taskmaster, he was probably the first male mentor Jane had had since she’d lived in California.

By her second year at Cooper Union, Jane’s social life on the Upper East Side would become a distraction that did not impress her fellow students. For most of Jane’s Nightingale-Bamford classmates had become debutantes, participating in an elite ritual that still exists in several major cities today.

Filed under: Such Mad Fun Tagged: Austin Purves Jr., Cooper Union, Cooper Union Art School 1933, Jane Hall

February 4, 2016

A New World at The Cooper Union

Whatever happened to the Nightingale-Bamford Class of 1932? Jane and one of her classmates described what they’d been up to for the school’s 1933 Year Book: Five of the sixteen girls entered women’s colleges: two were at Vassar, two at Sweet Briar and one at Sarah Lawrence. Two others were on a European trip with one of their mothers, one had married, and Betty Pearl, one of Jane’s good friends, “finds time between proms and bridge for an active interest in hospital work—she may end up as a sister of mercy yet!” Alice Drake, Jane’s co-author on the report, was “learning to punish a Remington, Corona, Underwood, Royal, or anything else available at Miss Conklin’s Secretarial School.” As for Jane, she “has been spending her time studying art in its Higher Aspects and writing letters of condolence to Mr. Hoover,” who had just turned the White House over to Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

In the early summer of 1932, the stock market hit bottom. Financial reverses and unexpected expenses in Virginia and New York had depleted Randolph Hicks’s savings. Although Jane had always dreamed of going to college, the costly private colleges that appealed to a handful of her classmates seemed impractical and unnecessary to him. The women the Hickses knew were supported by their husbands. But Randolph admired Jane’s sketches and drawings, so he and Rose encouraged her to try art school. How relieved they must have been when she was accepted at the all-scholarship Woman’s Art School of Cooper Union. Admission to the full-time four year course was by competitive examinations in spatial relations,vocabulary (reading comprehension), art judgment, and drawing. But the first year was provisional; each student would be evaluated again in the spring to see if the school was a good fit. In 1932, the Day Art School was still known as a “school for respectable females.” An aging Edith Wharton served on its Advisory Council; J.P. Morgan was one of the trustees.

Cooper Union Foundation Building

The Foundation Building of Cooper Union is an Italianate masonry brownstone that dominates a triangular-shaped pocket of Manhattan on Seventh Street between Third and Fourth Avenues. It was home to the arts and engineering schools, one of the best public reading rooms and libraries in Manhattan, and the Great Hall, the site of famous lectures including one by Abraham Lincoln that had set him on the path to the presidency. Most Cooper students worked during the day and studied at night, giving the school its “proletarian” atmosphere; even in the Day Art School, according to a lengthy 1937 New Yorker profile of the campus, there were “no wealthy pupils.” Founded in 1869, Cooper Union remains dedicated to the advancement of science and art, to the principle that education should be available to the average (talented) person at no cost.

The students dressed in what today would be considered business attire, with the women wearing skirts, blouses, or dresses, and the young men jackets and slacks. Even so, the atmosphere could not have been more different on the Lower East Side than it had been on Carnegie Hill. Jane Hall began her daily commute to Cooper Union on the Lexington Avenue IRT (or possibly the Fifth Avenue bus) to Astor Place, perhaps with warnings from her aunt to stay clear of the Bowery. There the unemployed congregated, and questionable types populated the sidewalks and shops, desperate to pawn, sell or exchange whatever they could for an illicit beer or something more nourishing.

Jane was intrigued by the energy of the neighborhoods that surrounded Cooper, filled as they were with the scents of ethnic food and people of different national origins—Italians, Slavs, East European Jews, Russians, Poles, Greeks and Hungarians. These were the merchants, grocers, machinists, and the bus and taxi drivers whose labor built New York and kept it moving, and whose wives’ and daughters’ sewing machines made the clothes that filled the city’s department stores. Manhattan’s Lower East Side was a mix of pushcarts, tiny shops and larger industrial buildings, squalid cold-water flats, tenements, and a few elegant homes that remained near Astor Place. Cooper Union was also an easy walk to the East Village, Washington Square and Union Square, to several secondhand bookstores, Wanamaker’s Department Store and McSorley’s Old Ale House where no women would be served until 1970.

But Jane joined the Class of 1936 at a time of transition.The art school had just hired a new director and the Day Art School was about to become coeducational – at least in name. (The men would prefer the Night Art School as they no doubt all held jobs or wanted to find them.) The school year began at the beginning of October and ended in the middle of May; classes started promptly at 9 A.M. and ended at 4 P.M. with a one hour break for lunch at noon.

Jane’s adventures there begin in the next post.

Postscript: I am grateful to David Chenkin and Carol Salomon at Cooper Union for helping me get the facts right about the Day Art School in the mid-1930s. There are no annual reports for these years.

Filed under: Such Mad Fun Tagged: Cooper Union 1932, Jane Hall, Lower East Side Manhattan 1932, NIghtingale Bamford Class of 1932, R. Randolph Hicks, Woman's Art School Cooper Union

January 11, 2016

From Tomboy to Glamour Girl

“A valuable, absorbing contribution to the history of women, golden-age Hollywood, and America’s magazine culture of the 1930s and ’40s.” KIRKUS starred review.

SUCH MAD FUN RELEASES 9/8 FOR ADVANCE REVIEWS CLICK HERE.

What determines who a woman will become?”Jane Hall was an orphan at fifteen and a “literary prodigy” according to the press. How did this daughter of Arizona’s most popular humorist become a Depression-era debutante, a successful author of magazine fiction, and a screenwriter at Hollywood’s most glamorous studio? Jane soon found that her ambition conflicted with the expectations of her family, her friends and the era in which she lived. Devastated by the loss of her parents, how long would it take Jane to trust her emotions and love again? Share some of her adventures by starting on the overview page for Such Mad Fun or scrolling through the posts. And be sure to check out the Gallery.

Such Mad Fun: Ambition and Glamour in Hollywood’s Golden Age

Review copies: Angelle Barbazon

JKS Communications

angelle@jkscommmunications.com

(615) 928-2462

Filed under: Such Mad Fun Tagged: 1930s, Bradshaw Crandell, Cosmopolitan, featured, Hollywood, Jane Hall, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, MGM, Poplar Springs, Such Mad Fun

January 10, 2016

Dick Wick Hall – “A man who made the whole world laugh”

To learn more about Jane’s father, Arizona’s favorite humorist in the 1920s, scroll through to earlier posts. Check out the Such Mad Fun Gallery. And see The Laughing Desert: Dick Wick Hall’s Salome Sun. Available on Amazon, this replica of the syndicated 1925-1926 news sheet is packed with stories, poems, humor, hometown philosophy, and engaging illustrations that made the town of Salome famous. The book, which was part of Arizona’s Centennial celebration in 2012, includes family photographs that have never been seen before and some of Dick’s love poems to his wife Daysie. Arizona’s Official State Historian and a popular entertainer, Marshall Trimble, provides the Foreword. Or click on this post and you will find out why his life story almost became a movie starring Will Rogers.

Filed under: Such Mad Fun Tagged: Dick Wick Hall, featured, Salome Arizona, The Laughing Desert, Will Rogers

Watch the Trailers for Movies Featured in Such Mad Fun

Watch for movies Jane worked on including HOLD THAT KISS, THESE GLAMOUR GIRLS, IT’S A DATE AND NANCY GOES TO RIO on TCM. (Open this post and click on the titles to see the trailers here.) Often they are for sale on TCM, Amazon or Ebay especially THESE GLAMOUR GIRLS which features Lana Turner in her first starring role. The movie is based on Jane’s book-length Cosmopolitan novel. At MGM she was hired by top producers like Sam Zimbalist and Joe Pasternak.

Filed under: Such Mad Fun Tagged: "Nancy Goes to Rio", "These Glamour Girls", featured, Hold That Kiss, It's a Date, Jane Hall, Lana Turner, TCM Classic Films

May 26, 2015

“In Righte Gude Fellowshipe . . .”

The Hickses were thrilled that Dick Wick Hall, Jr., would attend Randolph’s alma mater, The University of Virginia. Once he was settled in Charlottesville, Jane and her aunt and uncle returned to New York and moved to a new apartment at 1100 Park Avenue near Jane’s new school. At the beginning of October, Jane put on a blue or grey shirtwaist dress and headed just four blocks away to The Nightingale-Bamford School. She joined a class of just 15 other young ladies from privileged backgrounds in a much smaller setting than she had known at Redondo Union High School. In 1930 the girls were quite sheltered from the problems faced by the city’s public schools where 1,250,000 students had begun their academic year on September 8.

The Nightingale-Bamford School Today

A year earlier, the school had reopened in its brand-new six-story neo-Federal style red-brick building designed by Delano and Aldrich, one of the city’s foremost architectural firms. Frances Nicolau Nightingale and Maya Stevens Bamford had worked tirelessly to build a school that emphasized truth, friendship and loyalty (Veritas Amicitia Fides remains the motto), as well as academic excellence, the arts, and physical education– including good posture. They put education first; the parent-driven social life of their pupils was something they lived with reluctantly.

Between Monday and Thursday the girls were not allowed “to give a party, go to a party, or to the theater or moving pictures” after school. For despite the worsening economy, more Nightingale graduates in the Class of 1932 would be presented to Society than went to college—hopefully, as debutantes, they would meet young men from prominent families with promising futures. At least that’s what their parents had in mind.

Though the formal program ended at 1:15, art classes, dramatics, glee club, supervised study hours, and athletics filled the afternoons. On four days of the week, students could buy a hot lunch for $.75. Opposite the day school was a house used as a “very small Boarding Department” for up to ten young women who needed a place to stay during the week, but lived near enough to Manhattan to return home on the weekends.

Jane plunged right into activities at which she excelled – her talent as an amateur artist and wordsmith attracted notice right away. She became assistant editor of Chirps, a literary magazine, and was art editor of the 1932 Year Book. (Two of her poems and her art work came out in Chirps.) The seniors in the Class of ‘31 named Jane the “friendliest” girl in the school; tall, poised Jane (“Jamie”) Voorhees gladly bequeathed her “a few inches from her height” in the annual tongue-in-cheek Senior Will. Jane’s performance in A. A. Milne’s “The Ivory Door” and her role as the lamp in “And the Lamp Went Out, a Pantomime in One Act” inspired her fellow juniors to predict she would be another Lynn Fontanne, the celebrated stage and screen actress who often worked with her husband Alfred Lunt.

But the challenge of being a writer would now be more difficult. Just before leaving California for New York, Jane had bought Where and How to Sell Manuscripts – a Directory for Writers by William B. McCourtie. It was full of practical advice and an annotated list of periodicals in every conceivable category. Carefully, she checked off the names of magazines that might accept what she wrote and penciled in a list of her submissions at the back of the book. During the summer of 1931—one of a half-dozen she would spend at Poplar Springs– sixteen-year-old Jane mailed her poems, stories, articles and humor from the tiny Casanova post office to several of these magazines. At first, her efforts did not make it into print. As she competed in this new adult literary world, accolades from her teachers and her friends became vital to her fluctuating morale.

Jane Hall’s 1932 Year Book Photo

So Jane must have been pleased when four samples of her work appeared in the 1932 Nightingale Year Book. There was also a page for each of the 16 graduating seniors. Quotations under their profiles drew attention to the girls’ personalities. “In righte gude fellowshipe could she laughe and carpe all day,” read Jane’s, source unknown. The rest of her page sums up her two years: “Jane blew in from California last year, late as usual. However, on account of her numerous talents, this lapse of temperament can and must be overlooked. Jane draws and writes amazingly well, but sometimes throws us all . . .into fits of extreme melancholy, by means of her distressing talent for puns. Yet Jane and her artistic ability have saved the Year Book more than once this year from utter destruction. And what a sense of humor girl possesses.”

And now she would be off to The Womans’ Art School at Cooper Union on Manhattan’s Lower East Side–what a change that would be.

Filed under: Such Mad Fun Tagged: 1930s, Jane Hall, Manhattan 1930s, New York Private Schools 1930s, Nightingale-Bamford, Poplar Springs