Kate Elliott's Blog, page 21

April 17, 2013

Publishers’ Weekly reviews COLD STEEL (with a star)

The first review of COLD STEEL (publication date: June 25*) has appeared in the wild, and I’m thrilled to say that it is a starred review from Publishers Weekly.

Here is a link to the actual review (it has mild spoilers).

And here a pair of quotes:

Elliott wraps up her marvelous Spiritwalker trilogy (Cold Magic; Cold Fire) with triple helpings of revolution, romance, and adventure on an alternate Earth where elemental fire and cold mages vie for power, and revolution is in the air.

. . . .

Elliott pulls out all the stops in this final chapter to a swashbuckling series marked by fascinating world-building, lively characters, and a gripping, thoroughly satisfying story.

* It is probable that print copies will show up in bookstores a bit earlier, based on the drop for Cold Fire, but ebooks will drop on 25 June.

Mirrored from I Make Up Worlds.

April 15, 2013

Katharine Kerr’s Deverry sequence (Spiritwalker Monday 10)

Starting with Daggerspell (1986), this epic fantasy series of fifteen novels follows events in the land of Deverry over hundreds of years while maintaining a storyline that wraps tightly around itself in the manner of Celtic interlace.

Rather than describe the plot or characters, let me explain why I believe those of you who have not read this series should absolutely pick up the first book.

1) After reading through fifteen volumes with many characters, I can still name and describe ALL of the major characters and many of the minor ones because I became so invested in their stories. Memorable characters with compelling story-lines equals a gripping series.

2) Kerr’s world is not static. Her technique is subtle but assured as she unfolds how a culture changes over time. Villages become towns become cities. Warbands expand into armies. The political structure of the early kingdom shifts from more localized centers of regional power to a more centralized kingship. The spinning wheel is invented. When my spouse, an archaeologist, read Daggerspell, he said, “This is the best depiction of a chieftain-level society I’ve ever read.”

3) In other words, the world feels real and acts real. As with the world in Sherwood Smith’s Inda series, I believe Deverry could exist somewhere. After reading the books, I feel as if I have been there. I still think about events and dramatic moments in this series frequently, rather as I do memories from my actual life. That’s how much the narrative worked its way into my mind and heart.

4) This series offers a master class in how to use third person omniscient narration.

5) Not only has Kerr done her linguistics homework but she has fun with it. Do enjoy the asides in the prefaces that discuss pronunciation and language. Names and pronounciations change over time, and different societies have different languages and thus different names and different ways of speaking. It’s all woven seamlessly into the whole, not at all intrusive or awkward.

6) An extremely well drawn and workable magic system whose practitioners become adepts because of the degree of study and work they put in rather than through “natural talent.” While it is true that some people have an affinity for magic, you can’t become powerful through “chosen-ness.”

7) Dragons.

Dwarven women. Not at all what you think.

Dwarven women. Not at all what you think.

9) Some of the societies we meet in Deverry are patriarchal and yet Kerr continually gives women important roles and a variety of roles. Her women characters have agency.

10) Not all of the societies we meet in the series are patriarchal. They are varied, and unique, and interesting, with their own histories and languages (see 5, above)

11) The way she creates the institution of the “silver daggers” (disgraced men forced to “hire themselves out for coin”–which is seen as dishonorable in this society) and then threads it through the entire sequence. Brilliant.

12) In the early books especially, all politics are local, and lords’ warbands are fairly small groups of fighting men. Kerr, a football (NFL) fan, used her observations of the dynamics of football teams and games as part of the way in which she created the relationships between the warriors and the way battles — before, during, and after — are fought. It’s not noticeable. I just happen to know she did it, and for me the way she delves into the psychology and tactics and strategy of warfare in this type of society comes across as quite realistic and never cliched or stereotyped.

13) Which Deverry hero is the hottest? A lengthy discussion (may contain spoilers). This post was part of deverry15, an online tribute to the Deverry sequence upon publication of the final volume.

14) You can read through deverry15′s posts and links HERE.

15) The Deverry sequence is probably my favorite post-Tolkien epic fantasy series.

WHAT ARE YOU WAITING FOR?

[I would love to do a read-through of the entire series (the kind of thing they've been doing for a while not at Tor.com with other epic fantasy series, mostly by men) but at the moment I do not have time to administer it.]

Mirrored from I Make Up Worlds.

April 13, 2013

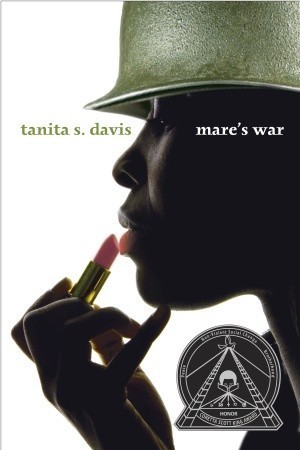

Tanita S Davis: MARE’S WAR

Two teen sisters who don’t really get along that well are forced by their parents to accompany their eccentric grandmother on a cross country trip, thus ruining their summer vacation plans.

Along the way, their grandmother begins telling them the story of how and why she left home and joined the Women’s Army Corps (WACs) in World War II with the 6888th, the only “all-African-American, all female unit to serve overseas.”

I really adored Mare’s War, which is a Young Adult contemporary fantasy (combined with a YA historical) There are two narrators: Younger sister Octavia tells the “Now” story and Mare (the grandmother) tells the “Then” story. This is not a dark, grim novel although it deals with serious subject matter. It’s sometimes funny, always humane, and the ending packs an emotional punch. (It brought good tears to my eyes.)

The dynamic between the sisters felt real to me and never became tedious or overwhelming. Their relationship with their grandmother, whom they do not quite understand or appreciate, is believably developed. Mare’s “then” story is engaging and vivid, and meanwhile Davis pulls off the difficult trick of educating the reader about a much overlooked piece of history without ever once making it feel didactic or educational.

I’m not particularly comfortable “reviewing” books. All I can say is that I highly recommend this novel. It’s an “easy read” without being simplistic (harder to pull off than it may seem), and a lovely story.

Mirrored from I Make Up Worlds.

April 9, 2013

On the efficacy of cold magic (Spiritwalker Monday 11)

By Habibah ibnah Alhamrai, natural philosopher and lecturer at the University of Expedition

It is well known that the great mage Houses are anathema to the technologies developed and developing in the Amerikes, especially those so abundantly useful in Expedition and other areas where the technologies have been employed. One might assume that the cause of this antipathy might be that much of these technologies are the handiwork of the Trolls, and that the mage have, in general, an inborn hatred or even natural dislike for their species. One would be totally mistaken.

The mages do not care about the Trolls except that they create and perpetrate many new technologies that the mages find repulsive, or rather that they find unuseable and from which they are repulsed. Part of this is undoubtedly physical, but some may be psychological in the sheer inescapability of their being cold mages. A common example of this physical repulsion can be seen in nearly any locale where gas light has been installed and is currently enhancing the environs of most normal citizens. We know that gas light is produced in lamps designed specifically to allow small amounts of gas to expand inside the globe and ignite and burn, thereby providing light and a bit of heat. The heat in this case is useless as the globes are high above the street, but the light, because of that height, shines down upon the ground and illuminates the surrounding area.

But watch a carriage carrying a cold mage through the streets and it is easy to see the problem. As the carriage approaches the light, the light dims. When the carriage is beneath the lamp, the light is nearly invisible. And when the carriage passes, only then does the light begin to brighten and eventually burn to its natural state.

It is widely known that cold mage houses are heated by an indirect method originally invented and employed by the Romans. It might be thought that they use this old style through some propensity toward ancient knowledge. That thought would be wrong. While it is unclear if the cold mages themselves would actually suffer much from the coldness, their spouses and children are not possessed of their abilities and certainly will. Therefore, cold mage manors must be heated in some way. This indirect method, though in some ways less efficient than direct heating by stove or fireplace, is nonetheless the only method available in an abode where cold mages reside. These Roman heat pipes are just that, pipes beneath the floors of the rooms that carry hot water or air. The heat source must be located somewhere away from the main house so that the cold magic cannot reach it, as not only will a cold mage put out a fire in near proximity, but it will also be impossible to relight the fire until the cold mage has departed. Generally, the mage houses place the fire building up hill from the house at a spring location so that water can be heated and then flow naturally down to the manor house itself. As far as can be understood, cold mages have had difficulty with fire for their entire existence, but, since little is known about the early days of the cold mages, little can be said as to how they adapted to their difficulties and adopted the Roman methods.

On the essence of cold magic, its spontaneous generation and use.

Cold magic is not an old ability. It did not exist during the height of the Roman hegemony. During that time, while various magics undoubtedly existed, cold magic did not. It is only due to the Salt Plague that cold magic could come into existence. One need not repeat here the history of the salt plague or the ghouls that emerged and destroyed entire civilizations. Nor the subsequent migrations and resettlements. The history may be read in any one of many treatises, but a simple explanation may be found in the workman-like discourse found in “Concerning the Mande Peoples of Western Africa Who Were Forced by Necessity to Abandon Their Homeland and Settle in Europe Just South of the Ice Shelf,” by Catharine Hassi Barahal of the famous Hassi Barahal Kena’ani lineage.

Let it be said that one fortuitous result of the plague, or rather the migration caused by the plague, is that the Mande from Africa met the Celtic druids of the north. Obviously, not all Mande were equal in either wealth or magic. The wealthy of the Mande married into the princely Celtic houses of the north, while those possessing magic found the Celtic druids to be of a kind, joined together with their societies and their houses. The combination led to the emergence of strong mages who had the ability to wield the power of the ice. This merging of two disparate elements formed the mage Houses.

However, not all or every merging of Mande with Celt produced or to this day produce cold mages and not all cold mages are equal. Because cold magic does not show up at birth, and because all joining does not produce a cold mage, the current mages have taken to occasionally plowing somewhat far from home and only reaping the outcome if it seems favorable. At this point, the lineages of the Celtic druids and the Mande run throughout many of the villages and towns within their realms so where a cold mage will appear is unknown. The biology of this phenomenon is undoubtedly fascinating but is not yet understood.

It is widely known that scholars believe that magic could be explicated on scientific principle if only those who handle magic were not so secretive. It is my thesis that much of cold magic can be explicated using only the principles of natural history and the sciences without the aid of the mages. In fact, help from the mages would probably serve only to further confuse.

For example, it is widely held by the mages and others that the source of cold magic is in the spirit world. That the source of the vast energies available to the mages is somewhere hidden in that world. The path to that energy may be in the spirit world, but the source of the power is the ice that covers the entire northern portion of our planet and on whose edge we settle. It is doubtful that if the Celtic druids had been the ones forced from their homes to settle in the Mande area of Africa that cold mages would today exist. Perhaps in that environ, the essence and control of fire magic might have become dominant. However, the vagaries of the gods forced the Mande to the north to sit on the edge of the source of their great power.

“The history of the world begins in ice, and it will end in ice.”

The Celtic bards and Mande djeliw of the north say this, but they do not know how correct they are. The Romans may have believed the world began in fire, but now, ice rules, as do the cold mages. The power of cold is extraordinary. Anyone in the proximity of a cold mage releasing his power will attest to this. Area wide storms of wind, ice and snow rain down upon those in the path of a cold mage’s ire. Liquid freezes and solid objects become so cold they brittlize and shatter. Through the spirit world and into the ice the mages reach, releasing the power. The ice is the ultimate source.

This is why one of the few things that a powerful cold mage fears is the Wild Hunt. The Wild Hunt will identify mages who overstep their bonds, who use their power too much, too often or too impulsively, and sweep down and remove that mage from the mix. We can not know the machination of those in the Wild Hunt nor the rest of their ilk, but they monitor and punish not just simple mortals, but the cold mages, for those of the Wild Hunt own the ice.

While I can not explain to you how the mages channel their power from the ice, nor whether that power is limited or limitless, I can explain their use of that power and why they themselves have a repulsion to fire and technology. We all know how fire can change metals in the forge or pottery in the kiln, but cold can do the same if wielded by a skilled mage. Take glass for example. For most of us, a broken pane of glass can only be repaired by remelting and pouring a new pane, but a cold mage can take those shards and knit them into a whole. How can this be done with cold rather than heat? We know that glass is amorphous, if the two edges are held together, the mage can make the components at the edges move and intertwine thereby fusing them together with intense cold. In this case, there are no crystals to reunite or layers to re-adhere. Just as the masses of ice on the glaciers move, melt and reform under the great mass of the ice, so a mage’s touch can cold press the glass into reforming.

One does not often see a mage re-forming glass, but one does see the effects of a mage’s presence on fire and technology. The principles of fire are well understood, but a short explanation is appropriate here. In general, heat, from a fire, friction of rubbing, concentrated sunlight or striking of flint on steel warms the material to be burned, and when the temperature rises sufficiently for the substance to become gaseous, the material ignites. The material remains lit and burns because the fire of burning itself provides more gaseous fuel for the fire. An easy example to see is a candle. An ember transferred from the fireplace ignites the wick which burns rapidly until it approaches the wax. The wax melts, moves up the wick, evaporates and ignites and the process continues until there is no wax left.

When mages enter areas where there is fire of any kind, the intense cold presence around them sucks all the warmth from the area. The flame can no longer consume the material, be it wood, candle wax or gas, because the heat is drawn into the mage and the fire dies. Fires cannot be lit in the presence of a mage because the cold aura prevents any of the materials from igniting. Even if a spark from flint can be created, the materials will not burn.

The effect of this sucking of energy on a fireplace fire or candle are transient and while the mages dislike them, they are merely annoying. The presence of large furnaces, like the ones created in Expedition to run the boilers that power the factories, contain much more energy, and while the mages have a similar effect on a factory as they do on a candle, the great heat absorbed by the mages is no longer simply annoying, but can begin to eat into their very essence. This, I believe, is why the mage Houses are so opposed to the new technologies. They fear first, that the presence of so much technology producing so much heat will interfere with their magic, but they fear foremost that the technology will become all pervasive and interfere with their well being, melting them and eroding them from inside.

###

@ A’ndrea Messer 2010

Science writer A’ndrea Messer wrote this piece “in the style of” an early 19th century paper or lecture. The character Habibah ibnah Alhamrai appears in Cold Fire.

A’ndrea and her colleagues at the Research Communications unit of The Pennsylvania State University have a blog: Research Matters.

Mirrored from I Make Up Worlds.

April 4, 2013

COLD MAGIC on sale (Kindle & Nook)

Today only (April 4) Cold Magic is on sale for $1.99 on at Amazon/Kindle and at B&N/Nook. AND at iBooks.

If you haven’t read it or if you read it from the library and want a copy or even just TELL YOUR FRIENDS (or enemies–whatever): Now’s your chance.

Now is a good time to start the series regardless if you’ve not read it yet, with COLD STEEL coming out in June. [And while the official publication date is June 25, if I go by the example of Cold Fire's soft launch back in Sept 2011, there's a chance the trade paperback will start hitting stores earlier although the ebook won't drop until the official day.]

Mirrored from I Make Up Worlds.

April 2, 2013

From: The Secret Journal of Beatrice Hassi Barahal (Spiritwalker Monday 12)

Cat Barahal, in the fencing salon (preliminary sketch by Julie Dillon)

I’m collaborating with fabulous (& now Hugo-nominated!) artist Julie Dillon on a chapbook (she’s illustrating, I’m writing) titled “The Secret Journal of Beatrice Hassi Barahal.” It will be published by Crab Tank.

If all goes well the chapbook should be available by the June 25, 2013 release of Cold Steel.

More details and information (including bonus art) forthcoming.

Please feel free to signal boost this, as I’m practically beside myself with excitement about Julie’s gorgeous art.

Also, if you think it is something you would buy either as a print or digital copy, please let me know in the comments.

Mirrored from I Make Up Worlds.

April 1, 2013

Spiritwalker Monday waits for Tuesday

My usual Spiritwalker Monday post will go up on Tuesday because of April Fools’ Day.

Mirrored from I Make Up Worlds.

March 27, 2013

Where Goeth Epic Fantasy?

There’s been a rush of talk recently about epic fantasy, as is usual, but between Twitter and blogs I’ve read a number of opinions and discussions and longer essays that focus on such issues as gritty, grimdark, rape, sexual violence, consensual sex, realism, gender, history, invisibility of women and people of color, marketing and store placement favoring male writers, and my old favorite excoriating the “crushing conservatism” of fantasy.

I wonder how great a range of voices I can hear and if I’m just hearing the same voices over and over (not that I mind them; they’re great).

(In fact, while I linked to a few above, please let me know of further links below)

The point of this post is to ask questions:

1) Do you read epic fantasy? Never, sometimes, often, depends?

2) What do you think epic fantasy does well? What do you think is missing from epic fantasy today? What would you like to see more of? Less of? What does epic fantasy mean to you, and where is it reaching its potential and where falling short?

One caveat. For those who give authors as example (which is fine) I’m going to count up how many references to men writers vs women writers because the one thing I can say for certain is that every conversation I have seen about epic fantasy skews heavily to references to men writers of the sub genre. I realize that this has a lot to do with sales and the simple fact that the bestselling authors in the subgenre are, by miles, men writers (and white male Western writers at that), but I just throw that out there.

Mirrored from I Make Up Worlds.

March 25, 2013

The Creole of Expedition: Part Two: Creating the Creole (Spiritwalker Monday 13)

As I worked on Cold Fire, I asked myself this question: Do I use a creole to represent the local language of Expedition or do I write people’s speech to be indistinguishable from Cat’s own?

There’s a lot more about how and why I asked and answered the question in Part One, which you can find here.

Ultimately I decided to use a creole to represent the speech of Expedition. At this point I had to ask myself a second question: Given that I am not a native speaker of nor intimately familiar with any of the actual Caribbean creoles spoken today or in historical times, how do I write a creole that will seem authentic within the text without being a clumsy imitation or offensive parody of actual creoles?

Let me first give a couple of quick definitions.

Oxford Dictionaries defines a pidgin as “a grammatically simplified form of a language, used for communication between people not sharing a common language. Pidgins have a limited vocabulary, some elements of which are taken from local languages, and are not native languages, but arise out of language contact between speakers of other languages.”

A creole, on the other hand, is “a mother tongue formed from the contact of two languages through an earlier pidgin stage.” (I would add “two or more” because that was certainly the case in Hawaii. Lest you wonder, Hawaiian Pidgin is a creole.)

A dominant culture: Taino.

My friend and fellow writer Katharine Kerr has done a great deal of research in linguistics (her Deverry epic fantasy series is a superb example of what you can do with language in a fantasy sequence that spans hundreds of years), so I asked for her advice. We both knew I could not possibly replicate any of the existing or historical Caribbean creoles and, in any case, given that the Spiritwalker Trilogy posits an extremely alternate history, the actual historical creoles would not fit regardless.

She suggested that I devise a creole unique to Expedition

Kerr wrote, “The dominant language in any creole is that of the dominant culture. What is your dominant culture?”

The city of Expedition was founded by a Malian fleet supplemented by Phoenician navigators and sailors. The fleet’s chief language would be a variant of modern day Bambara with some Punic loan words. But any trans-Atlantic trade and intercourse with Europa would be heavily influenced by the presence of Latin as the lingua franca (trade language) of continental Europa. However, because Expedition is a small territory on the island of Kiskeya (Hispaniola), the regional dominant culture in which it exists would that of the Taino because the Antilles (Caribbean) in this alternate universe is ruled by the Taino.

Therefore the first thing I decided was that a number of Taino words and phrases would be present as part of the every day language. These would be reinforced (insofar as I could) with elements of Taino culture that would have become part of the society of Expedition in that way cultures adapt, adopt, and blend to become something unique to a specific place. I could only pick a couple of things to give Taino names lest the plethora of new words become overwhelming for the reader, so besides words we already use in English that are of Taino derivation such as hurricane, hammock, and papaya, I highlighted Taino elements which would matter to the plot.

Taino words that are part of Expedition’s creole include:

maku (foreigner)

opia (spirit of an ancestor)

areito (dance, song, or festival)

batey (ceremonial plaza often associated with a local version of the ball game that was known throughout the Caribbean and Central American region). As an historical note I should mention that in the Dominican Republic the word batey came to mean the company towns associated with sugar cane fields and processing.

cemi (a sacred object)

behique/behica (shaman)(also used as meaning a fire mage)

cacique/cacica (chief; ruler; king/ female king of the same)

cobo (queen conch)

Some fish: pargo, cachicata, cajaya, anolis, carite, guinchos, barracudas

Bahama is a Taino place name. So possibly (likely) is Cuba (a shortened form of an older name), Habana, Boriken (Puerto Rico), and Kiskeya itself (the island we know as Hispaniola divided now into Haiti (from the Taino Ayiti) and the Dominican Republic).

The creole continuum.

However, the creole could not just be a peppering of words foreign to the English I was writing in. The creole as Cat heard it would have not just differences in vocabulary but differences in grammar, in word choice, and in the rhythms of its speech.

Fortunately through the miracle of the internet I had previously made the acquaintance of Dr. Fragano Ledgister, a professor at Clark Atlanta University and himself Anglo-Jamaican. In a similar way to Dr. Kustis Nishimura allowing me to pick his brains about the physics of cold magic and fire magic, Dr. Ledgister was exceedingly generous in answering my questions, offering insight both into language and into the Caribbean as he knows it, and it is really through his offices that I was able to develop the creole as it appears on the page.

As well, many details of the Caribbean are present because of things he shared with me, and while that is a subject for another post I will briefly mention that he introduced me to the many varieties of fruit commonly enjoyed on the islands that are not as well known elsewhere and which play such an important role in Andevai’s courtship of Cat.

Dr. Ledgister discussed the work of Mervyn Alleyne.

Alleyne’s classification of Jamaican English is that it operates at three levels: the hierolect, Standard Jamaican English, that differs from the international (British or American) standard primarily in terms of minor differences of vocabulary and usage. The mesolect, or generally understood creole, spoken by most people and heavily influenced by the standard language. The basilect, “di real raw-chaw Patwa” as my friend Hugh Martin put it, spoken by rural people and the less educated. Each level of language is going to be used in different social contexts.

Therefore there are three versions of the creole, an acrolect (the term that has replaced Alleyne’s hierolect), a mesolect, and a basilect.

Abby, on Salt Island, is a country gal. She speaks the basilect. She (and her brother, met on the airship) are the only people Cat encounters who speak the basilect. It is characterized by having a simpler grammar and more archaic elements. Besides including all the features of the mesolect, it drops linking verbs (except ‘shall’) and drops the “th” sound to “dat” and “di” and so on. Also, basilect speakers do not use past tense, only present tense (more on verb use below).

Almost all the people of Expedition speak the mesolect, the most common form that Cat hears. I’ll elaborate on its development below.

The acrolect is spoken by the most high status families in the old city of Expedition; technically, the Taino nobles speak the acrolect since they speak what might be termed “formal Latin”–that is, Taino who are not Expeditioners never speak in the creole. For instance, at the dinner party at townhouse in Expedition where General Camjiata is staying, the son of a Keita merchant house speaks mostly with “correct english” but ‘yee’ and ‘shall’ are still present in his speech.

People of Taino ancestry who are Expeditioners speak the creole the same as any other Expeditioners.

“Maku” (foreigners) are usually distinguished by not speaking the creole, although I allowed a few usages to creep into the speech of foreign-born residents of Expedition, most commonly the use of “gal” for “girl” or “woman,” the use of “yee” for “you,” and the generic use of “shall” as an all purpose verb (more on those below).

The building blocks.

I wanted to write a simplified creole that would not be too difficult for readers to parse or too distracting.

Dr. Ledgister pointed out that

A creole has a streamlined grammar because it starts out as a pidgin or lingua franca before becoming a birth tongue. (Pidgins combining a language of rule and vocabulary and grammar elements from several subordinate languages encourages simplicity.) It’s also liable to contain archaisms because it will retain terms from when it was first formed (Jamaican speech still has words last used in standard English in the 17th century, like peradventure).

With his help I focused on four elements (besides the presence of Taino words) to highlight which would thus distinguish the Expedition creole (in its mesolect form) from the language Cat speaks:

1. verbs and verb tenses

2. pronouns

3. word choice (substitute words and archaisms)

4. speech rhythms

Verbs

Simplifying grammar meant simplifying verb tenses. I need to emphasize that a simplified grammar used in a creole does not mean that the speakers of creole are ignorant, stupid, ill-educated, or demeaned; it is an element of the creole.

Dr. Ledgister: “One example of this is that verbs don’t decline. You have Abby say [in an early draft] “I does not like it that this man Drake, this maku, decides so quickly to make yee his sweet” where a Jamaican would say “Me doh like it dat dis man Drake decide so fas/ to make you his gyal” and a Trinidadian would say “Ah don’ like it dat dis man Drake decide so quick dat you his sweet girl.” My point here is that the verbs don’t decline.”

In the final published draft, Abby says, “I don’ like dat dis man Drake decide so quick to make yee he sweet gal.”

I came up with a simplified set of rules for myself to follow as I wrote:

1. Present tense should use the infinitive in all cases (without the “to” unless the “to” is called for). So: “we have” “he have” “you have”

2. While technically it should be “we be” and “you be,” I use “is” (because it is easier for speakers of standard English to read).

“I am” becomes “I’s.” “You are” becomes “you’s.”

We and they “is” depends but is often “We’s” or “they’s.”

“It is” and “It was” are contracted into “’tis” and “’twas”

3. Simple past works pretty much as in English.

I could have done more with the verbs but I figured that was enough.

Pronouns

Originally I had this challenging and exciting idea that the basilect (as spoken by Abby) would use Bambara pronouns to reflect the Malian ancestry of the majority of the early settlers in Expedition. But when I tried to write it, it just became impenetrable.

Instead I adapted the Bambara ‘you’–rendered as “i” (ee) in English transcription–by turning “you” into “yee.” Yee is used throughout all forms of the creole, my one hat tip to Bambara pronouns. I left all other subject pronouns the same as they are in American English.

Object pronouns I left generally the same, although on a case by case basis and depending on the rhythm of the sentence, the object pronoun could be replaced with the subject pronoun.

The possessive is generally replaced by the subject pronoun — “his book” becomes “he book” except in the case of “I” in which the object pronoun “me book” is used.

Word Choice (replacement words & archaisms):

Replacements words (words commonly used differently than we might use them):

GAL: “girl” (as in old enough to have sex) or “young woman” is always replaced by “gal” which becomes the local equivalent of an all-purpose term for girls/women in the general ages of 15 – late 20s.

Older people will usually refer to young adult males (ages circa 15 – 25, depending on the age of the older person) as “lad.” Young men refer to other young men as “men” and to young women their own age as “gals.” Young women, the same.

SHALL: this is an all purpose verb used where appropriate and often in place of verbs like “would” “ought” and so on.

DON’ : replaces “don’t” or “do not”

In general I tried to avoid “do” (and Abby, using the basilect, never uses “do”) but sometimes I left it in because it got too convoluted or hard to understand or choppy to take it out.

Instead of THINK people generally use RECKON

Archaisms:

People use some older locutions and/or regional words like “peradventure” and “arseness.”

In case you are wondering where “arseness” comes from, here a quote from our correspondence: “I just grabbed my copy of (Richard) Allsopp and was struck as I opened it by the Trinidadian term “arseness” for “stupidity” (or as most West Indians would say “stupidness”), that’s worth using!” And indeed it was!

Rhythm

When I had all these things in place, the rhythm took care of itself.

The grammatical patterns, the pronouns, and the adapted words themselves began to structure how people spoke. Once that happened, the rhythm of their speech took on a distinctive flavor and inflection. By the time I had finished writing Cold Fire, the people of Expedition had a way of speaking that sounded “natural” to my ear and that, more importantly, did not have the same rhythm as the speech used by Cat and other Europans.

Conclusions

There is a lot more detail I could go into but this post is already quite long. One of the best parts about corresponding with Fragano Ledgister was getting to read his anecdotes. [If you ever get a chance, ask him about meeting C. L. R. James.]

Not everyone will agree that the creole in Cold Fire works, nor need they do so. But for my part, considering it as an experiment and as a challenge for me as a writer, I felt good about the final result. Whatever else and no matter how it holds up, I am glad to have pushed myself past what I was comfortable attempting to write. In certain ways, making the effort was its own reward.

Mirrored from I Make Up Worlds.

March 18, 2013

Repeat, Recapitulate, Revision: What Patterns Can Be Seen In A Writer’s Work? (Spiritwalker Mo

Often an author is the wrong person to ask when a reader has a question about that author’s work. This is one reason I find conversations between readers so illuminating, as people throw ideas and interpretations back and forth about what they saw or did not see in a particular piece of fiction (or other art).

It is a truism that every reaction to a piece of art will be unique to the individual. One of the things I most love about the reading experience both as a reader–and as a writer listening to what readers have to say–is this diversity of reaction.

Reader A may pick up on a clever allusion that I intended while Reader B may draw a comparison or see thematic content that never once occurred to me as I was writing. Likewise if I am discussing with another reader a book that I as a reader loved or hated, we may both have loved–or hated–it but for different reasons or for similar reasons or we may disagree entirely and stand on opposite shores of love and hate.

For me that makes the act of reading not only a creative act but also (and perhaps more importantly) an act of creating a relationship with a book, for good, for bad, for indifference, for ambivalence, for whatever complex feelings the book may engender in you.

I can’t recall who said it but somewhere somewhen a writer opined (and I paraphrase) that “each writer has only one story that they tell over and over again, and if they are lucky, it is a big story” (that is, one with lots of room for internal variation rather than one that is all too clearly repetitive).

Now I don’t buy that statement but I do think each writer (and any artist) brings to the creative table a unique set of variables, their personality, their life experience, their knowledge, their cultural background, their individual way of looking at the world, their interests, their passions, their intensity, their rawness or their smoothness, their flaws and strengths, and so on.

If a reader reads along the career of a writer then certain patterns, certain ways of approaching the creative vision, certain familiar themes or narrative quirks or a particular way of using voice may emerge as characteristic of that writer’s work. Certain subjects or questions or concerns or fixations or narrative structures or prose styles may come up in more than one project. Or maybe it’s just that there is always a Manic Pixie Dream Girl Variant in one writer’s work and a sarcastic cynical misanthrope in another.

So here is a great question asked of me by a reader on Facebook:

MK asked:

ok. so I have a question I’ve always wanted to ask you. I’m just not sure if I can ask it properly… well, anyway here it comes: how come you’ve written so many, so different books starring the same guy?? because for me Bakhtiian, Bulkezu and Anji are like different studies of the same person. so, am I right or is it only my imagination??

Perhaps I am the wrong person to answer the question. As mentioned above, the author isn’t always the right person to talk about their own work.

My answer would be No, but also Yes.

Yes, all three of the characters mentioned are leaders from steppe nomad nations with expansionist tendencies. [My children have in the past teased me about having to put steppe nomads in all my projects.]

No, I don’t see the three characters as the same person at all. I see them as individuals who have distinct personalities and distinct plot arcs. If any one of them were (as it were) put into the place of one of the others in the other book(s), the plot would fall out very differently because that individual would deal in an entirely unique way with the circumstances and parameters they are presented with. They each have different goals and different ways of reaching those goals and of interacting with other people as allies or obstacles.

Also, as it happens, because I used 9th and 10th century European history as the inspiration for Crown of Stars, Bulkezu and his plot arc are adaptations of actual invasions into Eastern Europe by steppe nations whose names are not commonly known to us now because they did not linger in the more commonly-known historical imagination the way the Huns and Mongols have done.

However:

Yes, the three characters do have similarities. I would even go so far as to say that in some ways Bulkezu and Anji were a way for me to comment on and think about the Jaran books and the way I characterized and portrayed Bakhtiian as the hero.

People sometimes say that science fiction and fantasy is a genre in conversation with itself. I think there is truth to that, and I know that I certainly examine, investigate, interrogate, celebrate, and confront elements of the genre through my own writing.

In addition, however, I am always in conversation with myself about my earlier work.

My views are not static.

There are plot elements or characters or details I wrote twenty years ago that I would not write now (and a few that I wish I had written differently). As I have more time in the world I may begin to look at an idea from a different angle than I did before simply because my perspective has shifted or because I now see a broader vista or around corners that used to block my vision. Perhaps I reach a point where I believe I have the chops to write something in a more challenging way that I wasn’t able to pull off before.

My development as a writer happens in my fiction over time and through projects. It reflects my development as a human being. I hope I have learned, and that any experience and sensitivity and compassion and knowledge I have gained can more fully inform what I write as I continue to write.

As readers and writers, what do you see when you consider patterns and repetition in any given writer’s work? In your own?

As readers are you aware of small and large, subtle or obvious, ways in which writers have created a body of work that has something in common with itself as a whole piece–that is, not just as discrete works but as a larger tapestry of a creative vision? How do you reflect on your own changing creative vision?

Mirrored from I Make Up Worlds.