Justin Taylor's Blog, page 35

December 14, 2017

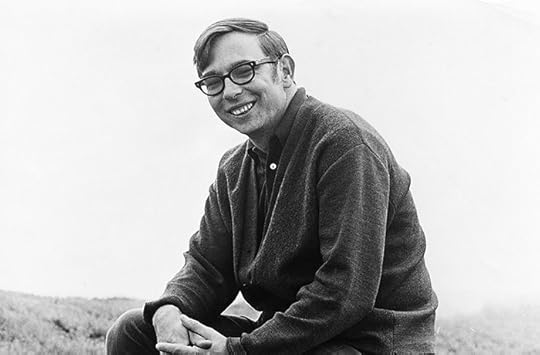

R. C. Sproul (1939–2017)

Presbyterian minister R.C. Sproul, one of the most influential popularizers of Reformed theology spanning the late 20th and early 21st centuries, entered into the joy of his Lord and Savior on December 14, 2017, following complications from emphysema. He was 78 years old.

Because he preached the whole counsel of God and had a heart to equip God’s people to live before the face of a holy God, he often taught on suffering and death over his five decades of ministry.

He once candidly admitted his fears when it came to dying:

I recently heard a young Christian remark, “I have no fear of dying.” When I heard this comment I thought to myself, “I wish I could say that.”

I am not afraid of death. I believe that death for the Christian is a glorious transition to heaven. I am not afraid of going to heaven. It’s the process that frightens me. I don’t know by what means I will die. It may be via a process of suffering, and that frightens me.

I know that even this shouldn’t frighten me. There are lots of things that frighten me that I shouldn’t let frighten me. The Scripture declares that perfect love casts out fear. But love is still imperfect, and fear hangs around.

He wrote about what it would be like to be in heaven and identified with Christ:

You can grieve for me the week before I die, if I’m scared and hurting, but when I gasp that last fleeting breath and my immortal soul flees to heaven, I’m going to be jumping over fire hydrants down the golden streets, and my biggest concern, if I have any, will be my wife back here grieving.

When I die, I will be identified with Christ’s exaltation. But right now, I’m identified with His affliction.

And in an article entitled “Death Does Not Have the Last Word,” he wrote:

When we close our eyes in death, we do not cease to be alive; rather, we experience a continuation of personal consciousness.

No person is more conscious, more aware, and more alert than when he passes through the veil from this world into the next.

Far from falling asleep, we are awakened to glory in all of its significance.

For the believer, death does not have the last word. Death has surrendered to the conquering power of the One who was resurrected as the firstborn of many brethren.

The mission, passion, and purpose of R.C. Sproul’s life was the same as Ligonier Ministries, the parachurch organization he helped to found in the 1970s: “to proclaim the holiness of God in all its fullness to as many people as possible.” He saw his work as a filling a gap between Sunday School and seminary, helping Christian laypeople renew their minds as they learned Christian doctrine, ethics, and apologetics, all in the service of living life coram Deo —before the face of God.

Robert Charles Sproul—called by his parents R. C. Sproul III—was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on February 13, 1939, the second child of Robert Cecil and Mayre Ann Sproul.

An avid Steelers and Pirates fan, sports were a big part of his life. But at the age of 15, R.C. had to drop out of high school athletics in order to help his family make ends meet, as his father, a veteran of World War II, had suffered a series of debilitating strokes. R.C. Sproul II—the most important figure in his son’s life—passed away during R.C.’s senior year of high school. His final words were, “Son, I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith.” R.C., who had watched his father faithfully read the Bible, had never read it himself and did not recognize that this was a quote from the Apostle Paul. He rebuked his father: “Don’t say that!” To his shame, it would be the last thing he ever said to father.

R.C. was reborn in September of 1957 during the first weekend of his first semester at Westminster College, a progressive Presbyterian school an hour north of Pittsburgh. Following freshman orientation, R.C. and his roommate (whom he had played baseball with in school) wanted to leave their dry campus to go to a neighboring town to drink. When they got to the parking lot, R.C. reached his hand in his pocket and realized he was all out of Lucky Strike cigarettes. They returned to the dorm, which housed a cigarette machine.

As he started to put his quarters in the machine, the star of the football team invited them to sit down at a table with him. He began asking them questions. They ended up talking for over an hour about the wisdom of God. What struck R.C. was that for the first time in his life, he was listening to someone who sounded like he knew Jesus personally. The football player quoted Ecclesiastes 11:3 (“Where the tree falls in the forest, there it lies”) and R.C. saw himself as that true: dead, corrupt, and rotting. He returned to his dorm that night and prayed to God for forgiveness. He would later remark that he was probably the only person in church history to be converted through that particular verse.

R.C. was biblically and theologically illiterate. Within the first two weeks of his Christian life, he read through the entire Bible, and was awakened for the first time to the holiness of God, especially through the Old Testament.

In February of 1958, R.C.’s girlfriend, Vesta—whom he met in first grade and had dated on and off since junior high—visited from her college in Ohio. After attending a prayer meeting with R.C., she too committed her life to Christ.

The summer after his junior year at Westminster and Vesta’s graduation from college, R.C. and Vesta were united in marriage on June 11, 1960.

The next year, Vesta worked at the school while R.C. wrote his senior philosophy thesis on “The Existential Implications of Moby Dick” and saw his beloved Pirates win the World Series.

In August of 1961 the Sprouls’ first child, Sherrie, was born, and R.C. enrolled at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, which was affiliated with the mainline United Presbyterian Church in the United States (the largest Presbyterian denomination in America at the time).

During seminary, he began taking classes with 47-year-old church history professor John Gerstner (1914–1996), a conservative Calvinist in the progressive school. R.C. was strongly opposed to Reformed theology

I challenged Gerstner in the classroom time after time, making a total pest of myself. I resisted for well over a year. My final surrender came in stages. Painful stages. It started when I began work as a student pastor in a church. I wrote a note to myself that I kept on my desk in a place where I could always see it.

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO BELIEVE, TO PREACH, AND TO TEACH WHAT THE BIBLE SAYS IS TRUE, NOT WHAT YOU WANT THE BIBLE TO SAY IS TRUE.

The note haunted me. My final crisis came in my senior year. I had a three-credit course in the study of Jonathan Edwards. We spent the semester studying Edwards’s most famous book, The Freedom of the Will, under Gerstner’s tutelage. At the same time, I had a Greek exegesis course in the book of Romans. I was the only student in that course, one on one with the New Testament professor. There was nowhere I could hide.

The combination was too much for me. Gerstner, Edwards, the New Testament professor, and above all the apostle Paul, were too formidable a team for me to withstand.

Sproul, the reluctant Calvinst, came to embrace Reformed theology and to view Gerstner as a lifelong theological mentor.

Although R.C. desired to enter pastoral ministry, Gerstner encouraged him to do doctoral work at the Free University of Amsterdam under G.C. Berkouwer (1903–1996), the leading Dutch theologian in the Reformed world. The Sprouls moved to Holland in 1964 to commence R.C.’s program.

But in just his second semester at the university, during the spring of 1965, R.C. was granted a one-year leave of absence to return to the United States, as Vesta was pregnant with her second child and R.C.’s mother was ill. He secured an appointment to teach philosophy at his alma mater, Westminster College, during this hiatus. That summer, on July 1, his mother passed into glory. And on the very same day, Robert Craig Sproul (R.C. Sproul Jr.), their only son, was born. Two weeks later, R.C. was ordained as a minister in the United Presbyterian Church in the USA. (He would join the PCA in 1975.)

Rather than returning to the Netherlands, the Sprouls stayed in the US, where he taught at Gordon College (Massachusetts) and then Conwell School of Theology (Philadelphia). He continued his studies under Berkouwer from a distance and returned in 1969 to take his matriculation exams, which enabled him to receive the “drs.” (doctorandus) degree—equivalent to a masters—which would have enabled him to begin writing a dissertation. But ministry endeavors prevailed, and he never did complete his dissertation and thus did not earn a PhD from Amsterdam. (He would later be granted a PhD from the unaccredited Whitefield Theological Seminary based upon all of his writing for the church.)

From 1969 to 1971, R.C. served as associate minister of theology and evangelism at College Hill Presbyterian Church in Cincinnati, Ohio. One person influenced by this ministry was Dora Hillman, a 65-year-old widow of an industrial tycoon in Pittsburgh.

In February of 1970, Mrs. Hillman visited R.C. and Vesta in Cincinnati to propose a plan in collaboration with other Christian leaders from the Pittsburgh area: a Christian study and conference center on 52 acres of land an hour east of Pittsburgh in the Ligonier Valley, with R.C. as the primary teaching theologian along with other staff.

The Sprouls accepted this calling and in 1971 moved to the small village of Stahlstown, an hour east of Pittsburgh. The Ligonier Valley Study Center was modeled in part after Francis Schaeffer’s L’Abri ministry in Switzerland. Students ate and slept in the Sprouls’ home and the other homes on the complex, while teaching happened both formally and informally throughout the week. A burgeoning audio ministry soon developed, and R.C. began traveling the country giving seminars and conferences.

The 1970s saw the beginning of R.C.’s writing career. The first several titles show the range of his teaching and interests: The Symbol: An Exposition of the Apostles’ Creed (P&R, 1973); The Psychology of Atheism (Bethany, 1974), Discovering the Intimate Marriage (Bethan, 1975), and The Inerrant Word, general editor (Bethany, 1975). He would go on to write or edit over 60 books, including a novel, a biography, and several children’s books.

The inerrancy volume grew out of a conference on the Inspiration and Authority of Scripture, hosted at Ligonier in the fall of 1973, with more than 100 guests. Speakers at the conference included John Gerstner, J. I. Packer, John Frame, and Clark Pinnock. R.C. penned the Ligonier Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, which was further refined and developed, culminating in the 1978 Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy.

On May 6, 1977, he Ligonier Valley Study Center launched a monthly newsletter, called Tabletalk after the informal teaching time of Martin Luther. The newsletter eventually became a magazine, with an estimated readership of a quarter of a million people across 50 countries.

In 1984, the Ligonier Valley Study Center was renamed Ligonier Ministries and relocated to Orlando, Florida. R.C., who taught four months out of the year at Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, Mississippi, became the first academic dean at the RTS Orlando campus, which began in 1989.

in 1985, Tyndale House Publishers in Wheaton, Illinois, published The Holiness of God, which may be his most important book.

In 1986, Tyndale published Chosen by God, which argued the case for a Calvinstic understanding of divine predestination.

He would later say that if someone was going to read anything by him, he would recommend these two books.

My biggest concern in writing all of the books that I’ve written is to help people understand who God is and who we are.

Those two books, I think, first of all point out the transcendent majesty of God, and second, the sovereignty of God.

Those two ideas so inform our whole understanding of God, of Christ, of ourselves, and of the whole gamut of Christian thought that it is the foundational material that I use to introduce people to these things.

One of the great distinctions of R.C.’s teaching style was his use of a chalkboard, even when technology had advanced far beyond this classroom tool. It enabled laypeople to feel as if they were in a classroom by Professor Sproul, who refused to talk down to them, peppering his lectures with Latin phrases, but doing so in such an engaging way that listeners were more likely to lean in than to tune out. A master pedagogue, he combined an earnest seriousness with an evident joy over the material and the act of convincing his audience to follow his line of argument. He often had a gleam in his eye, anticipating the “aha” moment when it all came together. He gave the impression that while he was deadly serious about the subject matter under consideration, he never took himself too seriously.

He once talked about his teaching style with Tim Challies:

When we talk about teaching style, I guess some people think about a carefully choreographed style for communication. I’ve never done that. My teaching style is just an expression of who I am. My concern is always to get my message across. The idea of walking around and using a blackboard started in my teaching of philosophy and Bible as a professor in a college.

I made ample use of the blackboard and chalk, and even to this day, I much prefer them over whiteboards and felt pens. I just like the dynamic of chalkboards. You can erase them easily, and there’s action involved.

I remember once I was lecturing in the college and my mind went blank—because I didn’t use notes, or very few notes in those lectures—and I didn’t know where I was. So I turned around and walked over to the blackboard—at that point, it was blank—and I took the chalk and wrote a long line and then put an exclamation point at the end of it.

I turned around and said to the class, “Do you know what that means?” And they looked at me with dumbfounded bewilderment. I said: “Let me tell you what it means. It means I forgot where I was, and I had to do something, so I just wrote this line on the blackboard. But now I remember, so we can continue.”

The daily radio program Renewing Your Mind first aired in 1994.

That same year, the ecumenical statement “Evangelical and Catholics Together” was unveiled, featuring not only Roman Catholic leaders like Avery Dulles and Richard John Neuhaus, but also friends of Sproul like Chuck Colson and J. I. Packer. R.C. saw the document as a compromise of the Gospel, undermining the essential truths of imputed righteousness through faith alone.

In 1995, R.C. served as the general editor of the New Geneva Study Bible (now revised and published as The Reformation Study Bible), after seven years of labor with over fifty biblical scholars.

In 1997, the new, small congregation of Saint Andrew’s Chapel called R.C. to serve as their senior minister of preaching and teaching. He later became the co-pastor with the appointment of Burk Parsons. The church sought to remain steadfast in the Reformed tradition but without the influence of denominational governance, though their pastors are ordained in the PCA. From their initial meetings within the recording studio at Ligonier, to a local movie theatre, they finally established their first sanctuary in 2001.

R.C. called this preaching ministry “the highlight of my life.” The great regret of his life was that he waited until he was 58 years old to proclaim God’s Word from the pulpit week in and week out.

In 2011, Ligonier launched Reformation Bible College, seeking to redefine what a Bible college can be by combining Reformed theology and piety with an academically rigorous curriculum.

A businessman once asked R.C. Sproul, “What’s the big idea of the Christian life?” He answered:

The big idea of the Christian life is coram Deo. Coram Deo captures the essence of the Christian life. . . .

This phrase literally refers to something that takes place in the presence of, or before the face of, God.

To live coram Deo is to live one’s entire life in the presence of God, under the authority of God, to the glory of God.

Today, R.C. Sproul—a sinner saved by grace alone through faith alone in Christ based on Scripture alone for the glory of God alone—is seeing his Savior face to face, and hearing the words we all long to hear: “Well done, my good and faithful servant. Enter into the joy of your Master.”

For further reading:

RCSproul.com

Chris Larson, “Dr. R.C. Sproul, Called Home to the Lord“

Stephen Nichols, “Remembering R.C. Sproul, 1939–2017“

W. Robert Godfrey, “A Letter from the Chairman of Ligonier Ministries“

Matt Smethurst, 40 Quotes from R.C. Sproul (1939–2017)

Burk Parsons, “R.C. Sproul: A Man Called by God“

Jack Rowley, “The Ligonier Valley Study Center Early Years“

John Piper, “Unashamed Allegiance: A Tribute to R.C. Sproul (1939–2017)“

Sinclair Ferguson, “Have You Heard of R.C. Sproul?“

Albert Mohler, “A Bright and Burning Light: Robert Charles Sproul, February 13, 1939––December 14, 2017”

John MacArthur, “A Tribute to My Friend“

Michael Horton, “R.C. Sproul: In Memoriam“

Ligon Duncan, “God’s Man, for God’s Work: A Tribute to R.C. Sproul (1939–2017)“

Mark Dever and Jonathan Leeman, “Remembering R.C. Sproul” (audio)

Jared Wilson, “The Numinous and R.C. Sproul“

Scott Swain, “In Memoriam: R. C. Sproul, Preacher and Teacher of a Thrice-Holy God“

Rick Phillips, “Lion in Our Midst: A Eulogy for R.C. Sproul“

Nicholas T. Batzig, “A Tribute to R.C. Sproul“

Tim Challies, “Next Time: A Tribute to R.C. Sproul“

Stephen Nichols, “The Launch of Ligonier’s ‘Tabletalk’ Magazine: 40 Years Later“

Stephen Nichols, “The Chicago Statement: An Interview with R.C. Sproul“

Mark Dever, “Life and Apologetics with R.C. Sproul“

Mark Dever: “Theology and Books with R.C. Sproul“

R.C. Sproul (1939–2017)

Presbyterian minister R.C. Sproul, one of the most influential popularizers of Reformed theology spanning the late 20th and early 21st centuries, entered into the joy of his Lord and Savior on December 14, 2017, following complications from emphysema. He was 78 years old.

Because he preached the whole counsel of God and had a heart to equip God’s people to live before the face of a holy God, he often taught on suffering and death over his five decades of ministry.

He once candidly admitted his fears when it came to dying:

I recently heard a young Christian remark, “I have no fear of dying.” When I heard this comment I thought to myself, “I wish I could say that.”

I am not afraid of death. I believe that death for the Christian is a glorious transition to heaven. I am not afraid of going to heaven. It’s the process that frightens me. I don’t know by what means I will die. It may be via a process of suffering, and that frightens me.

I know that even this shouldn’t frighten me. There are lots of things that frighten me that I shouldn’t let frighten me. The Scripture declares that perfect love casts out fear. But love is still imperfect, and fear hangs around.

He wrote about what it would be like to be in heaven and identified with Christ:

You can grieve for me the week before I die, if I’m scared and hurting, but when I gasp that last fleeting breath and my immortal soul flees to heaven, I’m going to be jumping over fire hydrants down the golden streets, and my biggest concern, if I have any, will be my wife back here grieving.

When I die, I will be identified with Christ’s exaltation. But right now, I’m identified with His affliction.

And in an article entitled “Death Does Not Have the Last Word,” he wrote:

When we close our eyes in death, we do not cease to be alive; rather, we experience a continuation of personal consciousness.

No person is more conscious, more aware, and more alert than when he passes through the veil from this world into the next.

Far from falling asleep, we are awakened to glory in all of its significance.

For the believer, death does not have the last word. Death has surrendered to the conquering power of the One who was resurrected as the firstborn of many brethren.

The mission, passion, and purpose of R.C. Sproul’s life was the same as Ligonier Ministries, the parachurch organization he helped to found in the 1970s: “to proclaim the holiness of God in all its fullness to as many people as possible.” He saw his work as a filling a gap between Sunday School and seminary, helping Christian laypeople renew their minds as they learned Christian doctrine, ethics, and apologetics, all in the service of living life coram Deo —before the face of God.

Robert Charles Sproul—called by his parents R. C. Sproul III—was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on February 13, 1939, the second child of Robert Cecil and Mayre Ann Sproul.

An avid Steelers and Pirates fan, sports were a big part of his life. But at the age of 15, R.C. had to drop out of high school athletics in order to help his family make ends meet, as his father, a veteran of World War II, had suffered a series of debilitating strokes. R.C. Sproul II—the most important figure in his son’s life—passed away during R.C.’s senior year of high school. His final words were, “Son, I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith.” R.C., who had watched his father faithfully read the Bible, had never read it himself and did not recognize that this was a quote from the Apostle Paul. He rebuked his father: “Don’t say that!” To his shame, it would be the last thing he ever said to father.

R.C. was reborn in September of 1957 during the first weekend of his first semester at Westminster College, a progressive Presbyterian school an hour north of Pittsburgh. Following freshman orientation, R.C. and his roommate (whom he had played baseball with in school) wanted to leave their dry campus to go to a neighboring town to drink. When they got to the parking lot, R.C. reached his hand in his pocket and realized he was all out of Lucky Strike cigarettes. They returned to the dorm, which housed a cigarette machine.

As he started to put his quarters in the machine, the star of the football team invited them to sit down at a table with him. He began asking them questions. They ended up talking for over an hour about the wisdom of God. What struck R.C. was that for the first time in his life, he was listening to someone who sounded like he knew Jesus personally. The football player quoted Ecclesiastes 11:3 (“Where the tree falls in the forest, there it lies”) and R.C. saw himself as that true: dead, corrupt, and rotting. He returned to his dorm that night and prayed to God for forgiveness. He would later remark that he was probably the only person in church history to be converted through that particular verse.

R.C. was biblically and theologically illiterate. Within the first two weeks of his Christian life, he read through the entire Bible, and was awakened for the first time to the holiness of God, especially through the Old Testament.

In February of 1958, R.C.’s girlfriend, Vesta—whom he met in first grade and had dated on and off since junior high—visited from her college in Ohio. After attending a prayer meeting with R.C., she too committed her life to Christ.

The summer after his junior year at Westminster and Vesta’s graduation from college, R.C. and Vesta were united in marriage on June 11, 1960.

The next year, Vesta worked at the school while R.C. wrote his senior philosophy thesis on “The Existential Implications of Moby Dick” and saw his beloved Pirates win the World Series.

In August of 1961 the Sprouls’ first child, Sherrie, was born, and R.C. enrolled at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, which was affiliated with the mainline United Presbyterian Church in the United States (the largest Presbyterian denomination in America at the time).

During seminary, he began taking classes with 47-year-old church history professor John Gerstner (1914–1996), a conservative Calvinist in the progressive school. R.C. was strongly opposed to Reformed theology

I challenged Gerstner in the classroom time after time, making a total pest of myself. I resisted for well over a year. My final surrender came in stages. Painful stages. It started when I began work as a student pastor in a church. I wrote a note to myself that I kept on my desk in a place where I could always see it.

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO BELIEVE, TO PREACH, AND TO TEACH WHAT THE BIBLE SAYS IS TRUE, NOT WHAT YOU WANT THE BIBLE TO SAY IS TRUE.

The note haunted me. My final crisis came in my senior year. I had a three-credit course in the study of Jonathan Edwards. We spent the semester studying Edwards’s most famous book, The Freedom of the Will, under Gerstner’s tutelage. At the same time, I had a Greek exegesis course in the book of Romans. I was the only student in that course, one on one with the New Testament professor. There was nowhere I could hide.

The combination was too much for me. Gerstner, Edwards, the New Testament professor, and above all the apostle Paul, were too formidable a team for me to withstand.

Sproul, the reluctant Calvinst, came to embrace Reformed theology and to view Gerstner as a lifelong theological mentor.

Although R.C. desired to enter pastoral ministry, Gerstner encouraged him to do doctoral work at the Free University of Amsterdam under G.C. Berkouwer (1903–1996), the leading Dutch theologian in the Reformed world. The Sprouls moved to Holland in 1964 to commence R.C.’s program.

But in just his second semester at the university, during the spring of 1965, R.C. was granted a one-year leave of absence to return to the United States, as Vesta was pregnant with her second child and R.C.’s mother was ill. He secured an appointment to teach philosophy at his alma mater, Westminster College, during this hiatus. That summer, on July 1, his mother passed into glory. And on the very same day, Robert Craig Sproul (R.C. Sproul Jr.), their only son, was born. Two weeks later, R.C. was ordained as a minister in the United Presbyterian Church in the USA. (He would join the PCA in 1975.)

Rather than returning to the Netherlands, the Sprouls stayed in the US, where he taught at Gordon College (Massachusetts) and then Conwell School of Theology (Philadelphia). He continued his studies under Berkouwer from a distance and returned in 1969 to take his matriculation exams, which enabled him to receive the “drs.” (doctorandus) degree—equivalent to a masters—which would have enabled him to begin writing a dissertation. But ministry endeavors prevailed, and he never did complete his dissertation and thus did not earn a PhD from Amsterdam. (He would later be granted a PhD from the unaccredited Whitefield Theological Seminary based upon all of his writing for the church.)

From 1969 to 1971, R.C. served as associate minister of theology and evangelism at College Hill Presbyterian Church in Cincinnati, Ohio. One person influenced by this ministry was Dora Hillman, a 65-year-old widow of an industrial tycoon in Pittsburgh.

In February of 1970, Mrs. Hillman visited R.C. and Vesta in Cincinnati to propose a plan in collaboration with other Christian leaders from the Pittsburgh area: a Christian study and conference center on 52 acres of land an hour east of Pittsburgh in the Ligonier Valley, with R.C. as the primary teaching theologian along with other staff.

The Sprouls accepted this calling and in 1971 moved to the small village of Stahlstown, an hour east of Pittsburgh. The Ligonier Valley Study Center was modeled in part after Francis Schaeffer’s L’Abri ministry in Switzerland. Students ate and slept in the Sprouls’ home and the other homes on the complex, while teaching happened both formally and informally throughout the week. A burgeoning audio ministry soon developed, and R.C. began traveling the country giving seminars and conferences.

The 1970s saw the beginning of R.C.’s writing career. The first several titles show the range of his teaching and interests: The Symbol: An Exposition of the Apostles’ Creed (P&R, 1973); The Psychology of Atheism (Bethany, 1974), Discovering the Intimate Marriage (Bethan, 1975), and The Inerrant Word, general editor (Bethany, 1975). He would go on to write or edit over 60 books, including a novel, a biography, and several children’s books.

The inerrancy volume grew out of a conference on the Inspiration and Authority of Scripture, hosted at Ligonier in the fall of 1973, with more than 100 guests. Speakers at the conference included John Gerstner, J. I. Packer, John Frame, and Clark Pinnock. R.C. penned the Ligonier Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, which was further refined and developed, culminating in the 1978 Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy.

On May 6, 1977, he Ligonier Valley Study Center launched a monthly newsletter, called Tabletalk after the informal teaching time of Martin Luther. The newsletter eventually became a magazine, with an estimated readership of a quarter of a million people across 50 countries.

In 1984, the Ligonier Valley Study Center was renamed Ligonier Ministries and relocated to Orlando, Florida. R.C., who taught four months out of the year at Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, Mississippi, became the first academic dean at the RTS Orlando campus, which began in 1989.

in 1985, Tyndale House Publishers in Wheaton, Illinois, published The Holiness of God, which may be his most important book.

In 1986, Tyndale published Chosen by God, which argued the case for a Calvinstic understanding of divine predestination.

He would later say that if someone was going to read anything by him, he would recommend these two books.

My biggest concern in writing all of the books that I’ve written is to help people understand who God is and who we are.

Those two books, I think, first of all point out the transcendent majesty of God, and second, the sovereignty of God.

Those two ideas so inform our whole understanding of God, of Christ, of ourselves, and of the whole gamut of Christian thought that it is the foundational material that I use to introduce people to these things.

One of the great distinctions of R.C.’s teaching style was his use of a chalkboard, even when technology had advanced far beyond this classroom tool. It enabled laypeople to feel as if they were in a classroom by Professor Sproul, who refused to talk down to them, peppering his lectures with Latin phrases, but doing so in such an engaging way that listeners were more likely to lean in than to tune out. A master pedagogue, he combined an earnest seriousness with an evident joy over the material and the act of convincing his audience to follow his line of argument. He often had a gleam in his eye, anticipating the “aha” moment when it all came together. He gave the impression that while he was deadly serious about the subject matter under consideration, he never took himself too seriously.

He once talked about his teaching style with Tim Challies:

When we talk about teaching style, I guess some people think about a carefully choreographed style for communication. I’ve never done that. My teaching style is just an expression of who I am. My concern is always to get my message across. The idea of walking around and using a blackboard started in my teaching of philosophy and Bible as a professor in a college.

I made ample use of the blackboard and chalk, and even to this day, I much prefer them over whiteboards and felt pens. I just like the dynamic of chalkboards. You can erase them easily, and there’s action involved.

I remember once I was lecturing in the college and my mind went blank—because I didn’t use notes, or very few notes in those lectures—and I didn’t know where I was. So I turned around and walked over to the blackboard—at that point, it was blank—and I took the chalk and wrote a long line and then put an exclamation point at the end of it.

I turned around and said to the class, “Do you know what that means?” And they looked at me with dumbfounded bewilderment. I said: “Let me tell you what it means. It means I forgot where I was, and I had to do something, so I just wrote this line on the blackboard. But now I remember, so we can continue.”

The daily radio program Renewing Your Mind first aired in 1994.

That same year, the ecumenical statement “Evangelical and Catholics Together” was unveiled, featuring not only Roman Catholic leaders like Avery Dulles and Richard John Neuhaus, but also friends of Sproul like Chuck Colson and J. I. Packer. R.C. saw the document as a compromise of the Gospel, undermining the essential truths of imputed righteousness through faith alone.

In 1995, R.C. served as the general editor of the New Geneva Study Bible (now revised and published as The Reformation Study Bible), after seven years of labor with over fifty biblical scholars.

In 1997, the new, small congregation of Saint Andrew’s Chapel called R.C. to serve as their senior minister of preaching and teaching. He later became the co-pastor with the appointment of Burk Parsons. The church sought to remain steadfast in the Reformed tradition but without the influence of denominational governance, though their pastors are ordained in the PCA. From their initial meetings within the recording studio at Ligonier, to a local movie theatre, they finally established their first sanctuary in 2001.

R.C. called this preaching ministry “the highlight of my life.” The great regret of his life was that he waited until he was 58 years old to proclaim God’s Word from the pulpit week in and week out.

In 2011, Ligonier launched Reformation Bible College, seeking to redefine what a Bible college can be by combining Reformed theology and piety with an academically rigorous curriculum.

A businessman once asked R.C. Sproul, “What’s the big idea of the Christian life?” He answered:

The big idea of the Christian life is coram Deo. Coram Deo captures the essence of the Christian life. . . .

This phrase literally refers to something that takes place in the presence of, or before the face of, God.

To live coram Deo is to live one’s entire life in the presence of God, under the authority of God, to the glory of God.

Today, R.C. Sproul—a sinner saved by grace alone through faith alone in Christ based on Scripture alone for the glory of God alone—is seeing his Savior face to face, and hearing the words we all long to hear: “Well done, my good and faithful servant. Enter into the joy of your Master.”

For further reading:

RCSproul.com

Chris Larson, “Dr. R.C. Sproul, Called Home to the Lord“

Stephen Nichols, “Remembering R.C. Sproul, 1939–2017“

W. Robert Godfrey, “A Letter from the Chairman of Ligonier Ministries“

Matt Smethurst, 40 Quotes from R.C. Sproul (1939–2017)

Burk Parsons, “R.C. Sproul: A Man Called by God“

Jack Rowley, “The Ligonier Valley Study Center Early Years“

Mark Dever, “Life and Apologetics with R.C. Sproul“

John Piper, “Unashamed Allegiance: A Tribute to R.C. Sproul (1939–2017)“

Albert Mohler, “A Bright and Burning Light: Robert Charles Sproul, February 13, 1939––December 14, 2017”

Nicholas T. Batzig, “A Tribute to R.C. Sproul“

Tim Challies, “Next Time: A Tribute to R.C. Sproul“

Scott Swain, “In Memoriam: R. C. Sproul, Preacher and Teacher of a Thrice-Holy God“

Rick Phillips, “Lion in Our Midst: A Eulogy for R.C. Sproul“

Stephen Nichols, “The Launch of Ligonier’s ‘Tabletalk’ Magazine: 40 Years Later“

Stephen Nichols, “The Chicago Statement: An Interview with R.C. Sproul“

November 22, 2017

What If We All Pitched in to Help Young Urban Adults Make More Disciples of Jesus Christ?

I’ve long been a fan of The Legacy, a ministry that “exists to equip disciples of Christ to make disciples for Christ.”

We train young, urban adults to develop life-on-life relationships through holistic discipleship.

At conferences and online, The Legacy unites diverse ministers to facilitate teaching on subjects such as disciple-making, biblical manhood and womanhood, evangelism, hermeneutics, community impact and doctrine.

Their statement of belief is the five solas of the Reformation.

Their annual conference has traditionally been in Chicago, but now they are looking to expand into five regional annual conferences by 2020 in order to make it more accessible to their target audience: young urban adults.

They are creating ongoing content to be posted on their website and through the Legacy Disciple app to continue to equip the urban church to grow as disciples of Christ and to make disciples for Christ.

If you want to help, they provide staffing and the resources to make this happen, they have just launched a Patreon, is seeking to mobilize up to 450 partners to give $10/ month or more.

For some of us, this is an opportunity to stop merely complaining or lamenting and start putting our money where our mouth is.

November 21, 2017

Serving the Families of Inmates: A Great Idea that Churches Should Try

Kudos to Matt Anderson and Holy Spirit Episcopal Church in Waco, Texas, who are throwing a community barbecue for the family members of inmates at the McLennan County jail—and inviting local law enforcement officers to help with the serving.

To raise the funds to pull this off, they need a little help. You can donate here.

Wouldn’t it be beautiful, healing, servant-hearted, and Christ-honoring if more churches caught a vision like this?

November 20, 2017

Fair-Minded Criticism Is an Acquired Taste that Can Become One of Life’s Best Pleasures

I love this article by David Powlison: “Does the Shoe Fit?” (Journal of Biblical Counseling [Spring 2002]: 2-14).

Here is how it begins:

Critics are God’s instruments. I don’t like to be criticized. You don’t like to be criticized. Nobody likes to be criticized.

But, critics keep us sane—or, by our reactions, prove us temporarily or permanently insane. Whether a critic’s manner is gracious or malicious, whether the timing is good or bad, whether the intention is constructive or destructive, whether the content is accurate, half-true, or utterly false, in any case the very experience of being criticized reveals you.

After looking at what criticism reveals about us, he also explores the great gift of fair-minded criticism:

Fair-minded criticism is one of life’s best pleasures, an acquired taste well worth the acquiring.

Someone who will take you seriously, understand you accurately, treat you charitably, and who then will lay it on the line is a messenger from God for your welfare (whether or not you end up completely agreeing).

There is nothing quite like being disagreed with intelligently, lovingly, and openly: “Faithful are the wounds of a friend” (Prov. 27:6).

If I only listen to my allies, or to yes-men, clones, devotees, and fellow factionaries, then I might as well inject narcotics into my veins. The people of God are a large work in progress. To engage and to interact with critics is to further the process—in both of our lives. We ought to offer to others the kind of criticism that is such a pleasure to receive.

Whenever we disagree with others our goal ought to be fair-minded, knowledgeable, constructive criticism (tinged with mercy, attentive to perceived strengths as well as perceived failings, openly receptive to reciprocal criticism). We all know this when doing marriage counseling. Jesus’ log-and-speck analysis and His call to clear-seeing helpfulness dig to the roots of every marital conflict. But we often ignore the log-and-speck in other spheres of controversy—or when in the midst of our own marital conflicts! Whether we write, teach, or converse, we often either succeed or derail based on the manner in which we deliver the matter. May we do as we would like it done to us.

Critics, like governing authorities, are servants of God to you for good (Rom. 13:4). He who sees into hearts uses critics to help us see things in ourselves: outright failings of faith and practice, distorted emphases, blind spots, areas of neglect, attitudes and actions contradictory to stated commitments, and, yes, strengths and significant contributions. God uses critics to help us. Even if I think that a criticism is mistaken, I shouldn’t leap too quickly to the defense.

Is there something I am doing or saying (or not doing and not saying) that makes that particular misinterpretation plausible?

Am I too easily misunderstood?

Do I leave implicit or understated something that needs to be made explicit?

Does my attitude or tone or way of treating people send a mixed message?

Do I ride my hobby horses?

Am I not answering some important question that this person is asking?

Am I not addressing some important problem that this person cares about?

In my experience, the answer to these questions is usually Yes.

You can read the whole thing here.

November 3, 2017

The Sequel to Chariots of Fire: A New Film Starring Joseph Fiennes Tells the Rest of Eric Liddell’s Story

In 1981, the Oscar-Award-winning Chariots of Fire recounted the true story of Eric Liddell (1902–1945), who refused to run in the heats for the 100-meter race during the 1924 Summer Olympics because they were held on a Sunday, which would have violated his Christian faith. Liddell ended up competing in the 400 meters, held during a weekday, and won the race.

Most people don’t know that Liddell, who was born in China to Scottish missionaries serving with the London Missionary Society, returned to China in 1925 at the age of 23. He died at the age of 43 in a Japanese civilian internment camp in 1945.

In a new film, On Wings of Eagles—which apparently releases today—Joseph Fiennes plays Liddell, portraying the second half of his life.

Information about the film is hard to find online, but here is an description from last year:

“Eric Liddell—China’s first gold medalist and one of Scotland’s greatest athletes—returns to war-torn China.

Film star Joseph Fiennes is to play the devoutly Christian Scottish runner Eric Liddell in a sequel to the multiple Oscar-winning Chariots of Fire.

On Wings of Eagles follows the life of Liddell after the 1924 Paris Olympics, when he won gold in the 400 metres but sacrificed his chance in the 100 metres because he refused to run on the Sabbath.

Joseph Fiennes, son of a Protestant father and Catholic and who is married to a Catholic, has been cast as Liddell in the film, which will include a central story line about his work as a missionary in China, where leading companies have given their backing to the film.

The script is by Chinese writer Stephen Shin, who will also direct alongside Canada’s Michael Parker. “It is not only the perfect movie theme, but it should also make younger generations more aware of their past. All around the world people gradually forget the importance of staying on alert so that dark parts of human history do not repeat themselves,” Shin told the Independent.

Liddell, the son of Rev and Mrs James Dunlop Liddell, was born in China to two Scottish missionary parents in China with the London Missionary Society. He was sent to the UK to be educated from the age of six, where he quickly showed excellence as an athlete and became known as The Flying Scotsman. After he went back to China he married another Christian, Florence Mackenzie, and helped to build an athletics stadium modelled on Chelsea’s Stamford Bridge.

After Japan invaded China in 1937 he was sent to an internment camp in 1943 where he died of a brain tumour in 1945, aged just 43. Many in China, both religious and non-religious, regard him as a hero because of his leadership during his internment as well as because of his sporting prowess.

Fienne’s co-stars will be Xiao Dou and Elizabeth Arends.”

To find theaters playing the movie in its limited release, try going here.

The post The Sequel to Chariots of Fire: A New Film Starring Joseph Fiennes Tells the Rest of Eric Liddell’s Story appeared first on The Gospel Coalition.

October 25, 2017

Do the Next Thing

Years ago, Elisabeth Elliot (1926-2015) popularized an old poem—the commonsense simplicity and clarity of which have encouraged many anxious and weary saints.

From an old English parsonage down by the sea

There came in the twilight a message to me;

Its quaint Saxon legend, deeply engraven,

Hath, it seems to me, teaching from Heaven.

And on through the doors the quiet words ring

Like a low inspiration: “DO THE NEXT THING.”

Many a questioning, many a fear,

Many a doubt, hath its quieting here.

Moment by moment, let down from Heaven,

Time, opportunity, and guidance are given.

Fear not tomorrows, child of the King,

Trust them with Jesus, do the next thing

Do it immediately, do it with prayer;

Do it reliantly, casting all care;

Do it with reverence, tracing His hand

Who placed it before thee with earnest command.

Stayed on Omnipotence, safe ‘neath His wing,

Leave all results, do the next thing.

Looking for Jesus, ever serener,

Working or suffering, be thy demeanor;

In His dear presence, the rest of His calm,

The light of His countenance be thy psalm,

Strong in His faithfulness, praise and sing.

Then, as He beckons thee, do the next thing.

The post Do the Next Thing appeared first on The Gospel Coalition.

Do the Next Thing

Years ago, Elisabeth Elliot (1926-2015) popularized an old poem—the commonsense simplicity and clarity of which have encouraged many anxious and weary saints.

From an old English parsonage down by the sea

There came in the twilight a message to me;

Its quaint Saxon legend, deeply engraven,

Hath, it seems to me, teaching from Heaven.

And on through the doors the quiet words ring

Like a low inspiration: “DO THE NEXT THING.”

Many a questioning, many a fear,

Many a doubt, hath its quieting here.

Moment by moment, let down from Heaven,

Time, opportunity, and guidance are given.

Fear not tomorrows, child of the King,

Trust them with Jesus, do the next thing

Do it immediately, do it with prayer;

Do it reliantly, casting all care;

Do it with reverence, tracing His hand

Who placed it before thee with earnest command.

Stayed on Omnipotence, safe ‘neath His wing,

Leave all results, do the next thing.

Looking for Jesus, ever serener,

Working or suffering, be thy demeanor;

In His dear presence, the rest of His calm,

The light of His countenance be thy psalm,

Strong in His faithfulness, praise and sing.

Then, as He beckons thee, do the next thing.

October 20, 2017

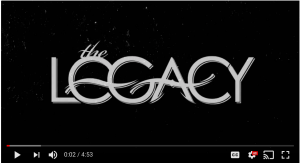

Four Smart Guys Sit Down to Talk about “How to Think”

Alan Jacobs, distinguished professor of the humanities in the honors program at Baylor University, has just published a book entitled How to Think: A Survival Guide for a World at Odds.

This morning the Wall Street Journal published an excerpt adapted from the book, asking “Can Evangelicals and Academic Talk to Each Other?”

The American Enterprise Institute recently sponsored an event where Jacobs gave a brief overview of the book, followed by a panel discussion about the book.

Jacobs is joined by two thoughtful public intellectuals—Jonathan Rauch of the Brookings Institution and Pete Wehner of the Ethics & Public Policy Center—and the discussion is moderated by the ever-thoughtful Yuval Levin of National Affairs.

After 10 minutes of introductory remarks by Jacobs, the panel chats for 35 minutes or so, followed by questions and answers from the audience.

In his TGC review of the book, Andrew Wilson reproduces some of the takeaways:

Think slowly.

When reading or listening to something you disagree with, give it five minutes before responding.

Give up trying to “think for yourself”; it’s impossible. Instead, belong to multiple communities so that your natural desire to have all your opinions validated by others is gently challenged.

Don’t underestimate, let alone try to eliminate, the emotional and relational components of thinking; they’re more important than we realize.

Recognize how your tendency to express solidarity with your “in-group” can close down critical reflection altogether.

Distinguish carefully between means and ends.

Act with the awareness that people who agree with you won’t always be in charge.

Choose your metaphors carefully; if you use military imagery for disagreement (won, lost, shot down, demolished, indefensible) or machine imagery for human brains, the metaphors will control your language and eventually your thought.

Avoid bad-faith habits like “in other wordsing” and “the false we.”

Before you critique another person’s argument, make sure you can express their argument to their satisfaction.

Spend more time with books, and less time online.

If you want to develop your thinking, develop your character.

If you are curious for what Jacobs thinks is “the number-one impediment to thinking,” here’s what he told Emma Green:

In a pluralistic society, people struggle to deal with difference. One of the ways in which we typically deal with difference is by drawing really clear lines of belonging and not-belonging. To be able to signal “who is with me” and “who is not with me”—in-groups and out-groups—is extremely significant for human beings.

(For more on the in-group, out-group, and far-group, see this post by Scott Alexander.)

Several years ago, John Frame wrote up some guidelines for his students on how to write a theological paper.

Here are a few that stand out and are worth emulating in the quest to become better writers, thinkers, and theologians.

Understand your sources.

Scripture texts ought to be fully exegeted. With other sources, I generally write out complete outlines of the ones that are most important. If I am reviewing a book (at some length, at least) I usually outline the entire volume, seeking to understand precisely the structure of the arguments, what is being said and how it is being said. Those sources which are less important, that is, those which will be referred to only in passing or of which only small portions are of interest, can be treated with proportionately less intensity; but the theologian is responsible to make correct use even of incidental sources.

Ask questions about your sources.

What is the author’s purpose?

What questions is he trying to answer, and how does he answer them? Try to paraphrase his position as best you can.

Is his position clear? Analyze any ambiguities.

What is he saying on the best possible interpretation? On the worst? On the most likely? . . .

Formulate a critical perspective on your sources.

How do you evaluate them? . . . There must always be some evaluation, positive or negative; if you don’t know what is good or bad about the source, you cannot make any responsible use of it. With a scriptural text as a source, of course, the evaluation should always be positive. With other texts, there will generally be some element of negative evaluation . . .

Ask, then, What do I want to tell my audience on the basis of my research?

Determine one or more points that you think your readers, hearers, viewers (etc.) ought to know. The structure of your presentation should be fully determined by that purpose. Omit anything extraneous. You do not need to tell your audience everything you have learned. Here are some things you might choose to do at this point.

(a) Ask questions. Sometimes a well-formulated question can be edifying, even if the theologian has no answer. It is good for us to learn what is mysterious, what is beyond our comprehension.

(b) Analyze a theological text or group of them. Analysis is not “exposition” (above) but “explanation.” It describes why the text is organized or phrased in a certain way—its historical background, its relations to other texts, and so forth.

(c) Compare or contrast two or more positions. Show their similarities and differences. (d) Develop implications and applications of the texts.

(e) Supplement the texts in some way. Add something to their teaching that you think is important.

(f) Offer criticism—positive or negative evaluation.

(g) Present some combination of the above. The point, of course, is to be clear on just what you are doing.

Be self-critical.

Before and during your writing, anticipate objections. If you are criticizing Barth, imagine Barth looking over your shoulder, reading your manuscript, giving his reactions. This point is crucial. A truly self-critical attitude can save you from unclarity and unsound arguments. It will also keep you from arrogance and unwarranted dogmatism—faults common to all theology (liberal as well as conservative). Don’t hesitate to say “probably” or even “I don’t know” when the circumstances warrant. Self-criticism will also make you more “profound.” For often—perhaps usually—it is objections that force us to rethink our positions, to get beyond our superficial ideas, to wrestle with the really deep theological issues. As you anticipate objections to your replies to objections to your replies, and so forth, you will find yourself being pushed irresistibly into the realm of the “difficult questions,” the theological profundities.

In self-criticism the creative use of the theological imagination is tremendously important. Keep asking such questions as these.

(a) Can I take my source’s idea in a more favorable sense? A less favorable one?

(b) Does my idea provide the only escape from the difficulty, or are there others?

(c) In trying to escape from one bad extreme, am I in danger of falling into a different evil on the other side?

(d) Can I think of some counter-examples to my generalizations?

(e) Must I clarify my concepts, lest they be misunderstood?

(f) Will my conclusion be controversial and thus require more argument than I had planned?

The post Four Smart Guys Sit Down to Talk about “How to Think” appeared first on The Gospel Coalition.

Four Smart Guys Sit Down to Talk about “How to Think”

Alan Jacobs, distinguished professor of the humanities in the honors program at Baylor University, has just published a book entitled How to Think: A Survival Guide for a World at Odds.

This morning the Wall Street Journal published an excerpt adapted from the book, asking “Can Evangelicals and Academic Talk to Each Other?”

The American Enterprise Institute recently sponsored an event where Jacobs gave a brief overview of the book, followed by a panel discussion about the book.

Jacobs is joined by two thoughtful public intellectuals—Jonathan Rauch of the Brookings Institution and Pete Wehner of the Ethics & Public Policy Center—and the discussion is moderated by the ever-thoughtful Yuval Levin of National Affairs.

After 10 minutes of introductory remarks by Jacobs, the panel chats for 35 minutes or so, followed by questions and answers from the audience.

In his TGC review of the book, Andrew Wilson reproduces some of the takeaways:

Think slowly.

When reading or listening to something you disagree with, give it five minutes before responding.

Give up trying to “think for yourself”; it’s impossible. Instead, belong to multiple communities so that your natural desire to have all your opinions validated by others is gently challenged.

Don’t underestimate, let alone try to eliminate, the emotional and relational components of thinking; they’re more important than we realize.

Recognize how your tendency to express solidarity with your “in-group” can close down critical reflection altogether.

Distinguish carefully between means and ends.

Act with the awareness that people who agree with you won’t always be in charge.

Choose your metaphors carefully; if you use military imagery for disagreement (won, lost, shot down, demolished, indefensible) or machine imagery for human brains, the metaphors will control your language and eventually your thought.

Avoid bad-faith habits like “in other wordsing” and “the false we.”

Before you critique another person’s argument, make sure you can express their argument to their satisfaction.

Spend more time with books, and less time online.

If you want to develop your thinking, develop your character.

If you are curious for what Jacobs thinks is “the number-one impediment to thinking,” here’s what he told Emma Green:

In a pluralistic society, people struggle to deal with difference. One of the ways in which we typically deal with difference is by drawing really clear lines of belonging and not-belonging. To be able to signal “who is with me” and “who is not with me”—in-groups and out-groups—is extremely significant for human beings.

(For more on the in-group, out-group, and far-group, see this post by Scott Alexander.)

Several years ago, John Frame wrote up some guidelines for his students on how to write a theological paper.

Here are a few that stand out and are worth emulating in the quest to become better writers, thinkers, and theologians.

Understand your sources.

Scripture texts ought to be fully exegeted. With other sources, I generally write out complete outlines of the ones that are most important. If I am reviewing a book (at some length, at least) I usually outline the entire volume, seeking to understand precisely the structure of the arguments, what is being said and how it is being said. Those sources which are less important, that is, those which will be referred to only in passing or of which only small portions are of interest, can be treated with proportionately less intensity; but the theologian is responsible to make correct use even of incidental sources.

Ask questions about your sources.

What is the author’s purpose?

What questions is he trying to answer, and how does he answer them? Try to paraphrase his position as best you can.

Is his position clear? Analyze any ambiguities.

What is he saying on the best possible interpretation? On the worst? On the most likely? . . .

Formulate a critical perspective on your sources.

How do you evaluate them? . . . There must always be some evaluation, positive or negative; if you don’t know what is good or bad about the source, you cannot make any responsible use of it. With a scriptural text as a source, of course, the evaluation should always be positive. With other texts, there will generally be some element of negative evaluation . . .

Ask, then, What do I want to tell my audience on the basis of my research?

Determine one or more points that you think your readers, hearers, viewers (etc.) ought to know. The structure of your presentation should be fully determined by that purpose. Omit anything extraneous. You do not need to tell your audience everything you have learned. Here are some things you might choose to do at this point.

(a) Ask questions. Sometimes a well-formulated question can be edifying, even if the theologian has no answer. It is good for us to learn what is mysterious, what is beyond our comprehension.

(b) Analyze a theological text or group of them. Analysis is not “exposition” (above) but “explanation.” It describes why the text is organized or phrased in a certain way—its historical background, its relations to other texts, and so forth.

(c) Compare or contrast two or more positions. Show their similarities and differences. (d) Develop implications and applications of the texts.

(e) Supplement the texts in some way. Add something to their teaching that you think is important.

(f) Offer criticism—positive or negative evaluation.

(g) Present some combination of the above. The point, of course, is to be clear on just what you are doing.

Be self-critical.

Before and during your writing, anticipate objections. If you are criticizing Barth, imagine Barth looking over your shoulder, reading your manuscript, giving his reactions. This point is crucial. A truly self-critical attitude can save you from unclarity and unsound arguments. It will also keep you from arrogance and unwarranted dogmatism—faults common to all theology (liberal as well as conservative). Don’t hesitate to say “probably” or even “I don’t know” when the circumstances warrant. Self-criticism will also make you more “profound.” For often—perhaps usually—it is objections that force us to rethink our positions, to get beyond our superficial ideas, to wrestle with the really deep theological issues. As you anticipate objections to your replies to objections to your replies, and so forth, you will find yourself being pushed irresistibly into the realm of the “difficult questions,” the theological profundities.

In self-criticism the creative use of the theological imagination is tremendously important. Keep asking such questions as these.

(a) Can I take my source’s idea in a more favorable sense? A less favorable one?

(b) Does my idea provide the only escape from the difficulty, or are there others?

(c) In trying to escape from one bad extreme, am I in danger of falling into a different evil on the other side?

(d) Can I think of some counter-examples to my generalizations?

(e) Must I clarify my concepts, lest they be misunderstood?

(f) Will my conclusion be controversial and thus require more argument than I had planned?

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers