Justin Taylor's Blog, page 307

July 28, 2011

An Interview with Nancy Guthrie

Nancy Guthrie will be live tonight for an hour on DG Live, from 7:00-8:30 EDT.

She will talk about their family's tear-inducing but hope-giving testimony and her latest book, The Promised One: Seeing Jesus in Genesis (Crossway, 2011), the first volume in the Seeing Jesus in the Old Testament Series. The 10-week Bible study will also be available on DVDs in August.

Hermeneutical Crucifixion and Salvation

Vern Poythress:

The growth of technique and of technical detail in interpretation may snare us into idolatry. We want interpretation without crucifixion. We trust in technical expertise and in method, in order to free ourselves from the fear of the agony of hermeneutical crucifixion. That is, we do not want to crucify what we think we already know and have achieved. We want painless, straightforward progress toward understanding, rather than having to abandon a whole route already constructed.

But the way of Christ is cross bearing. Christ offers us resurrection power, and hence the hope of renewing rather than losing the old. But the renewal always involves crucifixion. Many of us are too comfortable to be willing. . . .

Hermeneutical salvation, like all other aspects of salvation, is by grace alone. We act with hermeneutical responsibility only because God has acted on us, through the Spirit of Christ, the Redeemer (John 15:16; 6:37-40, 65). The beginning of the Christian life comes through God's grace, but progress after that beginning also comes through God's grace (Gal. 3:3). Far from eliminating work and excusing laziness, grace is the basis for vigorous and fruitful work, the work of scholarship, the work of meditation, the work of loving God, and the work of painful obedience in the world!

—Vern S. Poythress, God-Centered Biblical Interpretation (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1999), pp. 191-192, 222.

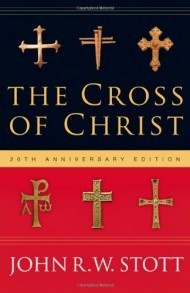

If You Can Only Read One of John Stott's Books

When a significant figure dies, for whatever reasons, his or her book sales often see an immediate spike.

When a significant figure dies, for whatever reasons, his or her book sales often see an immediate spike.

Some readers of this blog may feel that way, having come of age and come to Christ after John Stott had already retired from public ministry and wanting to taste for yourself the fruits of his labors.

If you feel that impulse, I'd encourage you to consider Stott's The Cross of Christ, republished a few years ago by InterVarsity Press in a 20th anniversary edition.

Endorsers can sometimes sound a bit hyperbolic, but you can tell from the commendations below that there is an earnestness and realism about the message and the ministry of this masterpiece.

"John Stott rises grandly to the challenge of the greatest of all themes. All the qualities that we expect of him—biblical precision, thoughtfulness and thoroughness, order and method, moral alertness and the measured tread, balanced judgment and practical passion—are here in fullest evidence. This, more than any book he has written, is his masterpiece."

—J. I. Packer, Regent College

"Rarely does a volume of theology combine six cardinal virtues, but John Stott's The Cross of Christ does so magnificently. It says what must be said about the cross; it gently but firmly warns against what must not be said; it grounds its judgments in biblical texts, again and again; it hierarchizes its arguments so that the main thing is always the main thing; it is written with admirable clarity; and it is so cast as to elicit genuine worship and thankfulness from any thoughtful reader. There are not many 'must read' books—books that belong on every minister's shelf, and on the shelves of thoughtful laypersons who want a better grasp of what is central in Scripture—but this is one of them."

—D. A. Carson, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School

"As relevant today as when it first appeared, The Cross of Christ is more than a classic. It restates in our own time the heart of the Christian message. Like John the Baptist, John Stott points us away from the distractions that occupy so much of our energies in order, announcing, 'Behold, the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!'"

—Michael Horton, Westminster Seminary California

"Biblical, clear and cogent are the words that came to mind on first reading this book. The passing of time has also made it indisputable that this book is a classic which is profound in a way that few evangelical books have been in recent years. It is compelling in its simplicity and comprehensive in its grasp of the way in which God conquers our sin, our rebellion, our ghastly evil through the person of Christ. Here is truth which is true, not just because it works for me, but because it is grounded in the very being and character of God, revealed and authenticated by him, worked out in the very fabric of our history, and therefore it is truth for all time."

—David F. Wells, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary

"I have no hesitation in saying that this is the most enriching theological book I have ever read. I read it slowly and devotionally over a period of several months. I found that it edified and challenged me, thrilled me with the glory of the cross, and equipped me to answer some of the questions non-Christians and skeptics ask about the cross. I am happy that a new thrust is being made to introduce this great book to a new generation of Christians."

—Ajith Fernando, Youth for Christ, Sri Lanka

July 27, 2011

Keith Green

29 years ago today the 28-year-old Christian singer and songwriter Keith Green went to be with the Lord, along with his two young children and another family.

Here's an hour-long documentary on his life:

It Is Not Death to Die

A hymn only Christians can sing and only because of Jesus:

It is not death to die,

To leave this weary road,

And midst the brotherhood on high

To be at home with God.

It is not death to close

The eye long dimmed by tears,

And wake, in glorious repose,

To spend eternal years.

It is not death to bear

The wrench that sets us free

From dungeon chain, to breathe the air

Of boundless liberty.

It is not death to fling

Aside this sinful dust

And rise, on strong exulting wing

To live among the just.

Jesus, Thou Prince of Life,

Thy chosen cannot die:

Like Thee, they conquer in the strife

To reign with Thee on high.

According to Cyberhymnal, the original words to this hymn were written in French by H. A. César Malan in 1832 (Non, ce n'est pas mourir que d'aller vers son Dieu). George W. Bethune translated them into English in 1847. The hymn was sung at Bethune's funeral, per his request.

Bob Kauflin wrote a contemporary rendition of the song on the Sovereign Grace Music album Come Weary Saints. You can listen to it below, followed by the revised lyrics:

It is not death to die

To leave this weary road

And join the saints who dwell on high

Who've found their home with God

It is not death to close

The eyes long dimmed by tears

And wake in joy before Your throne

Delivered from our fears

O Jesus, conquering the grave

Your precious blood has power to save

Those who trust in You

Will in Your mercy find

That it is not death to die

It is not death to fling

Aside this earthly dust

And rise with strong and noble wing

To live among the just

It is not death to hear

The key unlock the door

That sets us free from mortal years

To praise You evermore

John R. W. Stott (1921-2011)

John R. W. Stott, at the age of 90, went home to be with the Lord earlier today (3:15 PM London time, 9:15 AM CST).

Ten years ago Timothy Dudley-Smith, his longtime associate at All Souls Church, Langham Place, wrote the following about the essence of the man:

To those who know and meet him, respect and affection go hand in hand. The world-figure is lost in personal friendship, disarming interest, unfeigned humility—and a dash of mischievous humour and charm. By contrast, he thinks of himself, as all Christians should but few of us achieve, as simply a beloved child of a heavenly Father; an unworthy servant of his friend and master, Jesus Christ; a sinner saved by grace to the glory and praise of God. ("Who Is John Stott?" All Souls Broadsheet [London], April/May 2001)

Stott was confirmed in the Anglican Church in 1936, but was not converted until February 13, 1938, when he heard Rev. Eric Nash deliver an address to the Christian Union at Rugby School. Stott recalls:

His text was Pilate's question: "What then shall I do with Jesus, who is called the Christ?" That I needed to do anything with Jesus was an entirely novel idea to me, for I had imagined that somehow he had done whatever needed to be done, and that my part was only to acquiesce. This Mr Nash, however, was quietly but powerfully insisting that everybody had to do something about Jesus, and that nobody could remain neutral. Either we copy Pilate and weakly reject him, or we accept him personally and follow him.

After the address Stott was able to talk to Nash (who would become a mentor), who pointed Stott to Revelation 3:20. Nash asked him, "Have we ever opened our door to Christ? Have we ever invited him in?"

Stott later recalled:

This was exactly the question which I needed to have put to me. For, intellectually speaking, I had believed in Jesus all my life, on the other side of the door. I had regularly struggled to say my prayers through the key-hole. I had even pushed pennies under the door in a vain attempt to pacify him. I had been baptized, yes and confirmed as well. I went to church, read my Bible, had high ideals, and tried to be good and do good. But all the time, often without realising it, I was holding Christ at arm's length, and keeping him outside.

Later that night, at his bedside, Stott

made the experiment of faith, and "opened the door" to Christ. I saw no flash of lightning . . . in fact I had no emotional experience at all. I just crept into bed and went to sleep. For weeks afterwards, even months, I was unsure what had happened to me. But gradually I grew, as the diary I was writing at the time makes clear, into a clearer understanding and a firmer assurance of the salvation and lordship of Jesus Christ.

Stott went on to study at Trinity College, then Ridley Hall Theological College, at the University of Cambridge.

He was ordained in 1945, and became a curate at All Souls from 1945-50. He then served as rector at All Souls from 1950-75, becoming Rector Emeritus in 1975.

He also served as chaplain to the Queen from 1959 to 1991. In 1974 he founded Langham Partnership International and was one of the principal author of the Lausanne Covenant that same year.

He retired from public ministry in April of 2007 and had been living in a retirement community for Anglican clergy.

He never married and remained celibate his entire life, considering celibacy a vocation.

John Stott penned dozens of influential books and commentaries, the bestselling one being Basic Christianity, which was written in 1958 when Stott was 37 years old, and has sold over 2.5 million copies.

His outstanding book on preaching, Between Two Worlds, was published in 1982.

His most substantial book is probably The Cross of Christ (1986), about which J. I. Packer says, "No other treatment of this supreme subject says so much so truly and so well."

His final published words came at the end of his last book, The Radical Disciple, published in 2010:

As I lay down my pen for the last time (literally, since I confess I am not computerized) at the age of eighty-eight, I venture to send this valedictory message to my readers. I am grateful for your encouragement, for many of you have written to me. Looking ahead, none of us of course knows what the future of printing and publishing may be. But I myself am confident that the future of books is assured and that, though they will be complemented, they will never be altogether replaced. For there is something unique about books. Our favorite books become very precious to us and we even develop with them an almost living and affectionate relationship. Is it an altogether fanciful fact that we handle, stroke and even smell them as tokens of our esteem and affection? I am not referring only to an author's feeling for what he has written, but to all readers and their library. I have made it a rule not to quote from any book unless I have first handled it. So let me urge you to keep reading, and encourage your relatives and friends to do the same. For this is a much neglected means of grace. . . . Once again, farewell! (pp. 136-137)

Much more will be written in the days ahead about this servant of the Lord. (The first obituary has been penned by Tim Stafford at Christianity Today.) But no words of commendation will be as significant as the words John Stott heard earlier today: "Well done, my good and faithful servant. Enter into the joy of your master."

What It May Have Been Like to Hear the Letter to the Philippians for the First Time

Ray Ortlund:

. . . we can reconstruct in our imaginations the key moment in Philippi when this Christ-exalting outlook came home to those who first heard these words.

It is the Lord's Day in that great Macedonian city sometime in A.D. 62.

During the previous week Epaphroditus has returned from Paul in Rome, with this letter from the apostle in hand. The buzz has gone around the Christian network in town, and everyone is excited to hear the letter read aloud when the church gathers for worship.

They meet in Lydia's home this Sunday, seated together throughout the inner courtyard.

[Note: A virtual tour of such a house is available online.]

Euodia is there, as is Syntyche, but not yet sitting together (cf. Phil. 4:2).

This is a lovely but imperfect church.

As the believers gather, exchanges of greetings and small talk draw each one into the circle of fellowship.

Eventually, an elder stands and welcomes them all, prays, and leads them in a hymn of praise.

Then he asks Epaphroditus to step forward and join him at the front. Everyone claps and cheers, receiving him in the Lord with all joy (2:29). Epaphroditus, after giving a brief account of his journey and of Paul and his situation, relays Paul's greetings and formally presents the letter to the elders of the church. He resumes his seat.

The presiding elder then reads aloud Paul's letter, which requires only about fifteen minutes—less than a typical sermon in our churches today.

As the letter is read to everyone, in rapt attention, the Holy Spirit is speaking to their hearts. They start changing, at least a little, under the ministry of this letter. They become more willing than ever before, some of them dramatically more willing, to offer themselves to God by faith as a Christlike sacrificial offering. A hush settles over that courtyard, a solemn happiness, as the Spirit imparts a wonderful sense of the glory of Christ. They are worshiping.

Paul knew this would happen. He meant it to happen. He wanted to share in it.

Back in Rome, Paul is sitting in his prison cell on that same Lord's Day. He and Epaphroditus have discussed how long the return journey to Philippi may take. Paul figures that Epaphroditus is likely there by now. He goes there himself in memory and joins the meeting of his dear Philippian friends in heart and mind. Their faces—elders, deacons, members, children—pass before his mind's eye. He longs for them. He prays for them. And his deepest emotion, having years before settled the matter in his own heart that he is himself a living sacrifice—his deepest thought and feeling at this moment constitute a drink offering upon the sacrificial offering of their faith. The humility of the poured-out life has taken its rightful place of happy authority at the center of Paul's soul.

The great apostle does not feel that he is the important figure around which the Philippians ought to rally. They are the important ones. Their sacrifices seem to him greater than his own. He views their daily faith with awe, as they stand firm in one spirit, striving for the gospel, not running from conflict but engaged in it, shining as lights in their world, holding fast to the word of life.

Paul remembers how he first met them—pagans living as pagans must. He has watched the gospel transform them into "the saints of Christ Jesus who are at Philippi" (Phil. 1:1). Though Paul has witnessed these gospel miracles over and over again around the Mediterranean world (Col. 1:6), he is always moved by the saving power of God.

At this moment of quiet thought in his cell, his heart is swallowed up with a sense of privilege that he is being drawn into the only sacred and saving thing on the face of the earth. That he, a former blasphemer, persecutor, and insolent opponent (1 Tim. 1:13), is directly and personally participating in the outspreading grace of God in the world, raising up a bright new church out of the former human devastations of pagan Philippi—his sense of amazement exceeds his powers of utterance. Oh, that he would indeed be a drink offering on such a holy sacrifice!

Sitting there in his prison cell that day, Paul too is worshiping, as only a pastor can. Far from this removing him from his people, he feels bound to them profoundly.

Ray Ortlund, "The Pastor as Worshipper," in For the Fame of God's Name, ed. Sam Storms and Justin Taylor (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2010), pp. 414-416.

The Relationship Between "Love" and "Commandments" in the Writings of John

Jesus keeps his Father's commandments and abides in his Father's love

"I have kept my Father's commandments and abide in his love." (John 15:10b)

Jesus keeps his Father's commandments so that the world will know Jesus loves his Father

"I do as the Father has commanded me, so that the world may know that I love the Father." (John 14:31)

Jesus' new commandment: Love one another as you are loved by Jesus

"A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another: just as I have loved you, you also are to love one another." (John 13:34) "This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you." (John 15:12) "And this is his commandment, that we believe in the name of his Son Jesus Christ and love one another, just as he has commanded us." (1 John 3:23) "And now I ask you, dear lady—not as though I were writing you a new commandment, but the one we have had from the beginning—that we love one another." (2 John 1:5)

If you love Jesus you will keep Jesus' commandments

"If you love me, you will keep my commandments." (John 14:15)

Whoever keeps Jesus' commandments loves Jesus and is loved by the Father

"Whoever has my commandments and keeps them, he it is who loves me. And he who loves me will be loved by my Father, and I will love him and manifest myself to him." (John 14:21)

If you keep Jesus' commandments you will abide in Jesus' love

"If you keep my commandments, you will abide in my love. . ." (John 15:10a)

If you do what Jesus commands you will be his friend and will love one another

"You are my friends if you do what I command you. . . . These things I command you, so that you will love one another." (John 15:14, 17)

If you love God you must also love your brother

"And this commandment we have from him: whoever loves God must also love his brother." (1 John 4:21)

We know we love God's children when we love God and obey his commandments

"By this we know that we love the children of God, when we love God and obey his commandments." (1 John 5:2)

The love of God entails keeping his non-burdensome commandments

"For this is the love of God, that we keep his commandments. And his commandments are not burdensome. (1 John 5:3)

Love entails walking in and according to his commandments

And this is love, that we walk according to his commandments; this is the commandment, just as you have heard from the beginning, so that you should walk in it. (2 John 1:6)

How an Introvert Was Forced to Have Friends

An excerpt from Noël Piper's helpful article in Tabletalk:

I was sixty years old when this story began — when I was forced to have friends. I am ashamed that, until then, I could have remained so ignorant of what God intended friendship to be. At the same time, I am filled with gratitude that God didn't leave me alone.

Good things can happen in solitude. Quietness can be a sweet place to meet God. But there's a dark side to solitude when I crave it above all. The I comes to mean not "introvert" but literally only "I": I don't want you around, because I am the one who makes me happy. I can solve my own problems. I am all I need.

Right now as I lay those thoughts out so bluntly, I recoil from my arrogance. Do we really think, "I am all I need?," as if we were God?

O Lord, protect me from myself. Please help me to be still and know that you are God.

I am still an introvert. My dream day still is a day by myself, but only once in a while. I thank God for the women he gave me when I needed to receive friendship. I pray that God will shape my heart to give friendship like they do — like Jesus told us to: "By this all people will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another" (John 13:35).

Jesus said, "I have called you friends, for all that I have heard from my Father I have made known to you" (John 15:15). He is the one I most want as a friend. I don't want ever to be totally alone, without Jesus. I thank God for friends who have shown me Jesus' kind of love. They have been an appetizer for the feast of Jesus' friendship.

You can read the whole thing here.

See also Kevin DeYoung's blog series on "The Gift of Friendship and the Godliness of Good Friends":

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

July 26, 2011

Run, John, Run!

John Bunyan (1628-1688) is usually attributed with the following:

Run, John, run, the law commands

But gives us neither feet nor hands,

Far better news the gospel brings:

It bids us fly and gives us wings

I'm not sure, however, Bunyan ever wrote this profound and pithy summary. (I welcome any primary source documentation readers might have.)

It probably originated with the 18th century Scottish preacher Ralph Erksine (1685–1752):

A rigid matter was the law,

demanding brick, denying straw,

But when with gospel tongue it sings,

it bids me fly and gives me wings

—The Sermons and Practical Works of Ralph Erksine, vol. 10 (Glasgow: W. Smith and J. Bryce, 1778), 283.

Charles Spurgeon—who certainly knew his Bunyan—credits the more familiar version to English revivalist and hymnist John Berridge (1716–1793):

Run, John, and work, the law commands,

yet finds me neither feet nor hands,

But sweeter news the gospel brings,

it bids me fly and lends me wings!

—Cited in Charles H. Spurgeon, The Salt-Cellars: Being a Collection of Proverbs, Together with Homely Notes Thereon (London: Passmore and Alabaster, 1889), 200.

These references are owing to Jason Meyer's historical digging cited in his book The End of the Law: Mosaic Covenant in Pauline Theology (B&H, 2010), p. 2 n. 3.

Don't let the historical spadework distract you from this gospel jewel!

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers