Justin Taylor's Blog, page 295

August 29, 2011

Four Things for Journalists to Remember in Covering Religious Beliefs They Disagree With

First, conservative Christianity is a large and complicated world, and like other such worlds — the realm of the secular intelligentsia very much included — it has various centers and various fringes, which overlap in complicated ways. Sometimes teasing out these connections tells us something meaningful and interesting. But it's easy to succumb to a paranoid six-degrees-of-separation game, in which the most radical figure in a particular community is always the most important one, or the most extreme passage in a particular writer's work always defines his real-world influence.

Second, journalists should avoid double standards. If you roll your eyes when conservatives trumpet Barack Obama's links to Chicago socialists and academic radicals, you probably shouldn't leap to the conclusion that Bachmann's more outré law school influences prove she's a budding Torquemada. If you didn't spend the Jeremiah Wright controversy searching works of black liberation theology for inflammatory evidence of what Obama "really" believed, you probably shouldn't obsess over the supposed links between Rick Perry and R. J. Rushdoony, the Christian Reconstructionist guru.

Third, journalists should resist the temptation to apply the language of conspiracy to groups and causes that they find unfamiliar or extreme. Republican politicians are often accused of using religious "code words" and "dog whistles," for instance, when all they're doing is employing the everyday language of an America that's more biblically literate than the national press corps. Likewise, what often gets described as religious-right "infiltration" of government usually just amounts to conservative Christians' using the normal mechanisms of democratic politics to oust politicians whom they disagree with, or to fight back against laws that they don't like.

Finally, journalists should remember that Republican politicians have usually been far more adept at mobilizing their religious constituents than those constituents have been at claiming any sort of political "dominion." George W. Bush rallied evangelical voters in 2004 with his support for the Federal Marriage Amendment, and then dropped the gay marriage issue almost completely in his second term. Perry knows how to stroke the egos of Texas preachers, but he was listening to pharmaceutical lobbyists, not religious conservatives, when he signed an executive order mandating S.T.D. vaccinations for Texas teenagers.

This last point suggests the crucial error that the religious right's liberal critics tend to make. They look at Christian conservatism and see a host of legitimately problematic tendencies: Manichaean rhetoric, grandiose ambitions, apocalyptic enthusiasms. But they don't recognize these tendencies for what they often are: not signs of religious conservatism's growing strength and looming triumph, but evidence of its persistent disappointments and defeats.

You can read the whole thing here.

HT: Matt Anderson

Heaven in a Nightclub: The Roots and Theology of Jazz

In the video below Dr. William Edgar, Professor of Apologetics at Westminster Theological Seminary, gives a combination of piano concert and historical-theological lecture on the African-American musical heritage of pain and joy expressed through spirituals, jazz, ragtime, gospel, and blues. It was delivered at the Gordon College Convocation on February 20, 2009.

You can listen to an audio version of the same lecture delivered at the Chesterton House in 2007. In that version he plays with his quartet.

For a CD of the full concert, go here.

For related materials, see also Edgar's essay "The Deep Joy of Jazz" and Stephen Nichols's Getting the Blues: What Blues Music Teaches Us about Suffering and Salvation.

August 28, 2011

Three Things to Remember When Critiquing Someone's Theology

Critique—done well—is a gift to the one being criticized. We should welcome the opportunity to have our thinking corrected and clarified. We see through a glass dimly, and God has gifted the church with teachers who often see things more clearly than we do at present. In God's providence and through the gift of common grace he may also use unbelievers to critique our views, showing our logical mistakes or lack of clarity.

Critique done poorly—whether through overstatement, misunderstanding, caricature—is a losing proposition for all. It undermines the credibility of the critic and deprives the one being criticized from the opportunity to improve his or her position.

It's impossible in a blog post to set forth a comprehensive methodology of critique—if such a thing can even be done. But there are at least three exhortations worth remembering about criticism: (1) understand before you critique; (2) be self-critical in how you critique; (3) consider the alternatives of what you are critiquing.

1. Understanding Before You Critique

Mortimer Adler makes the important point in How to Read a Book:

Every author has had the experience of suffering book reviews by critic who did not feel obligated to do the work of the first two stages first. The critic too often thinks he does not have to be a reader as well as a judge. Every lecturer has also had the experience of having critical questions asked that were not based on any understanding of what he had said. You yourself may remember an occasion where someone said to a speaker, in one breath or at most two, "I don't know what you mean, but I think you're wrong."

There is actually no point in answering critics of this sort. The only polite thing to do is to ask them to state your position for you, the position they claim to be challenging. If they cannot do it satisfactorily, if they cannot repeat what you have said in their own words, you know that they do not understand, and you are entirely justified in ignoring their criticisms. They are irrelevant, as all criticism must be that is not based on understanding. When you find the rare person who shows that he understands what you are saying as well as you do, then you can delight in his agreement or be seriously disturbed by his dissent. (pp. 144-145)

I do think we have to add at least one caveat to Adler's perspective here. He is assuming goodwill upon the part of the one being criticized. In the last decade or so I've noticed theologians with novel interpretations or positions who perpetually protest that they are being misunderstood. At some point, we think the theologians doth protest too much. If not even the most careful and considerate critiques can understand one's point, it may be that there is some incoherence to the point itself. The idea that understanding and critiquing the theology of some folks is "like trying to nail jello to a wall" has now become a cliche—but the metaphor is apt and exists for a reason.

Nevertheless, Alder's perspective is one we need to hear and to heed in so far as it depends on us. Viewed from a biblical perspective, there are moral imperatives bound up with the act of reading and critiquing. Jesus tells me to do unto others as I would have done unto me, and he tells me to love my neighbor as I love myself—and this includes how I interact and critique.

2. Be Self-Critical

John Frame, in a piece on "How to Write a Theological Paper," makes the second point:

Be self-critical.

Before and during your writing, anticipate objections. If you are criticizing Barth, imagine Barth looking over your shoulder, reading your manuscript, giving his reactions. This point is crucial. A truly self-critical attitude can save you from unclarity and unsound arguments. It will also keep you from arrogance and unwarranted dogmatism—faults common to all theology (liberal as well as conservative).

Don't hesitate to say "probably" or even "I don't know" when the circumstances warrant. Self-criticism will also make you more "profound." For often—perhaps usually—it is objections that force us to rethink our positions, to get beyond our superficial ideas, to wrestle with the really deep theological issues.

As you anticipate objections to your replies to objections to your replies, and so forth, you will find yourself being pushed irresistibly into the realm of the "difficult questions," the theological profundities.

In self-criticism the creative use of the theological imagination is tremendously important. Keep asking such questions as these.

(a) Can I take my source's idea in a more favorable sense? A less favorable one?

(b) Does my idea provide the only escape from the difficulty, or are there others?

(c) In trying to escape from one bad extreme, am I in danger of falling into a different evil on the other side?

(d) Can I think of some counter-examples to my generalizations?

(e) Must I clarify my concepts, lest they be misunderstood?

(f) Will my conclusion be controversial and thus require more argument than I had planned?

3. What's the Alternative?

Millard Erickson, in his Christian Theology (p. 61) makes the third point

In criticism it is not sufficient to find flaws in a given view. One must always ask, "What is the alternative?" and, "Does the alternative have fewer difficulties?" John Baillie tells of writing a paper in which he severely criticized a particular view. His professor commented, "Every theory has its difficulties, but you have not considered whether any other theory has less difficulties than the one you have criticized."

Good criticism is hard work, and it's necessary work until Christ returns. The above three points won't prevent us from making every mistake, but they will help us be better critics and therefore better servants of God and truth.

August 27, 2011

Who Cares?

Perception vs. reality:

"Look to the right and see:

there is none who takes notice of me;

no refuge remains to me;

no one cares for my soul."

—Psalm 142:4

"Humble yourselves . . . under the mighty hand of God,

casting all your anxieties on him,

because he cares for you."

—1 Peter 5:6-7

August 22, 2011

How Do We Handle the Lurid and Crude Passages of Scripture

Ray Ortlund, who wrote a book on God's Unfaithful Wife: A Biblical Theology of Spiritual Adultery, answers, along with Sam Storms at the Clarus Conference in 2009:

The Freshman 15

Jeff Brewer offers wise counsel: "Dining hall food gets a bad rap, but incoming college freshmen don't seem to have a problem packing on the infamous 'freshman 15.' Honoring that tradition, here are 15 ways incoming freshmen (or upperclassmen for that matter) can seek to glorify God as they head off to college this month."

How Does the Gospel Speak to Suicide, Miscarriages, Abortion, and Abuse?

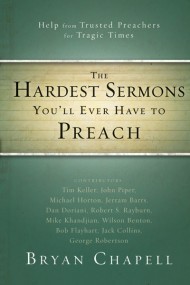

I am looking forward to reading this new book edited by Bryan Chapell, The Hardest Sermons You'll Ever Have to Preach: Help from Trusted Preachers for Tragic Times.

I am looking forward to reading this new book edited by Bryan Chapell, The Hardest Sermons You'll Ever Have to Preach: Help from Trusted Preachers for Tragic Times.

Cancer. Suicide. The death of a child. As much as we wish we could avoid tragedies like these, eventually they will strike your church community. When they do, pastors must be ready to offer help by communicating the life-changing message of the gospel in a way that offers hope, truth, and encouragement during these difficult circumstances. Those asked to preach in the midst of tragedy know the anxiety of trying to say appropriate things from God's Word that will comfort and strengthen God's people when emotions and faith are stretched thin. This indispensable resource helps pastors prepare sermons in the face of tragedies by providing suggestions for how to approach different kinds of tragedy, as well as insight into how to handle the theological challenges of human suffering. Each topic provides a specific description of the context of the tragedy, the key concerns that need to be addressed in the message, and an outline of the approach taken in the sample sermon that follows.

Topics addressed include:

abortion;

abuse;

responding to national and community tragedies;

the death of a child;

death due to cancer and prolonged sickness;

death due to drunk driving;

drug abuse; and

suicide.Bryan Chapell, author of Christ-Centered Preaching, has gathered together messages from some of today's most trusted Christian leaders including:

John Piper,

Tim Keller,

Michael Horton,

Jack Collins,

Dan Doriani,

Jerram Barrs,

Mike Khandjian,

Robert Rayburn,

Wilson Benton,

Bob Flayhart, and

George Robertson.Each chapter provides you with the resources you need to communicate the life-giving hope of the gospel in the midst of tragedy. In addition, the appendices provide further suggestions of biblical texts for addressing various subjects as well as guidance for conducting funerals.

Go here to read the full table of contents, Dr. Chapell's introduction, and his sermon on abortion.

The Unbelieving, Suffering Poor Deserve Better Than Bad Exegetical Arguments

John Piper: "This is a plea for the sake of the unbelieving, suffering poor. They should have better than bad arguments. Don't defend them with careless exegesis. Don't support them with pillars that cannot hold. Give them your best defense."

He looks briefly at three typically misplaced biblical pillars (Matt. 25:40; 1 John 3:17-18; James 2:15-16) a number of strong biblical pillars (Luke 6:27-31; Matt. 7:12; Matt. 5:16; Luke 10:25-37; Gal. 6:10; 1 Thess. 5:15).

August 21, 2011

The Critical Question for Our Generation

John Piper:

The critical question for our generation—and for every generation—is this:

If you could have heaven, with no sickness, and with all the friends you ever had on earth, and all the food you ever liked, and all the leisure activities you ever enjoyed, and all the natural beauties you ever saw, all the physical pleasures you ever tasted, and no human conflict or any natural disasters, could you be satisfied with heaven, if Christ were not there?

And the question for Christian leaders is: Do we preach and teach and lead in such a way that people are prepared to hear that question and answer with a resounding No?

J. C. Ryle:

But alas, how little fit for heaven are many who talk of going to heaven, when they die, while they manifestly have no saving faith and no real acquaintance with Christ. You give Christ no honor here. You have no communion with Him. You do not love Him. Alas, what could you do in heaven? It would be no place for you. Its joys would be no joys for you. Its happiness would be a happiness into which you could not enter. Its employments would be a weariness and a burden to your heart. Oh, repent and change before it be too late!

—John Piper, God Is the Gospel: Meditations on God's Love as the Gift of Himself (Wheaton, I: Crossway, 2005), p. 15.

—J. C. Ryle, from his sermon "Christ Is All" (on Col. 3:11), chapter 20 in Holiness: Its Names, Hindrances, Difficulties, and Roots (1877; reprint, Moscow, ID: Charles Nolan, 2001), p. 384.

August 20, 2011

Only Jesus

v1

When the trial comes

And all hope seems lost

I will find my strength

In the mighty cross

(chorus)

Only there

Only Jesus

Only there can i cast my burdens down

Only Him

Only Jesus

Only there is joy in sorrow found

v2

If my love grows cold

And my faith feels lost

I will find my heart

In the healing cross

words & music by marc heinrich

©2005 further up & further in music

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers