Justin Taylor's Blog, page 287

September 18, 2011

Pastors in the Classics

"Many pastors know the power of a well-chosen citation from Kierkegaard or Dostoevsky when preaching to others. But for pastors who are tired, discouraged, isolated, trapped in some lethal sin, or in danger of losing their faith, here is an ideal guide to find in the classics the deepest, most relevant, emotionally gripping wisdom to preach to oneself. May God use it to revive many of us, remind us of the height from which we have fallen, and restore us to our first love."

—Gordon P. Hugenberger, senior minister, Park Street Church, Boston

Seeing the Implied Assertions in Art

Leland Ryken, from his essay "The Creative Arts":

Works of art make implied assertions, just as history and science and philosophy do. For convenience, we can say that the arts make implied claims about the three great issues of life:

Reality: what really exists, and what is its nature?

Morality: what constitutes right and wrong behavior?

Values: what really matters, and what matters most and least?

For purposes of illustration, I turn first to a pair of nineteenth-century English painters, Constable and Turner. They both chose nature as their paintings convinces us not simply that physical nature is an important part of reality but also that it is something of great worth in human experience.

But along with these similarities we notice obvious differences in how Constable and Turner interpreted nature. What do we see as we look at Constable's famous paintings of Salisbury Cathedral?

We see the beauty and harmony of nature. We see nature in a religious light and as the friend of people. The human and natural worlds are unified. Constable himself said that he painted nature as benevolent because he sensed God's presence in nature.

Turner offers quite a different interpretation of nature. His colors are more intense, his brush strokes much broader and more passionate. There is an element of terror in many of his nature scenes. One of his paintings shows a gigantic avalanche ready to overwhelm a matchbox cabin under it furious weight.

In such a painting nature is not nurturing, as in Constable and the Dutch realists, but hostile. The one is not necessarily more Christian than the other, though we should not minimize how artists select details that suggest their overall view of human possibilities in the universe.

For a literary illustration, consider the following sonnet, entitled "God's Grandeur," by Gerard Manley Hopkins:

For a literary illustration, consider the following sonnet, entitled "God's Grandeur," by Gerard Manley Hopkins:

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil.

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man's smudge and shares man's smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights of the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs —

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World brooks with warm breast and with ah! bring wings.

The subject of the poem is the permanent freshness of nature.

The perspective from which we view that reality is the grandeur of God.

What really exists? According to this poem, the physical world of sun and tress and the spiritual world that includes the triune God are equally real.

What constitutes moral and immoral behavior? To live morally is to live in reverence before God's creation. To desecrate nature in pursuit of selfish acquisitiveness is immoral.

What values are most worthy of human pursuit? God's nature.

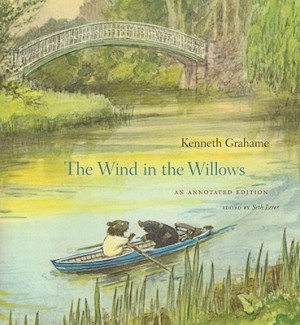

The Most Beautifully Written of All Children's Books

Alan Jacobs on Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows, published in 1908:

The Wind in the Willows is surely the most beautifully written of all children's books—it offers to the willing learner a deep course in the making of sentences. . . .

Gary Kamiya agrees:

It is apples and oranges to compare Grahame and the two other masters of genre-blurring imaginative prose, Tolkien and C.S. Lewis.

Grahame cannot rival Tolkien's epic grandeur, nor does he possess Lewis' double ability to create completely different imaginary worlds and weave vivid and intricate stories.

But neither of those geniuses handle English the way he does. Tolkien knows only the high style, and Lewis' solid prose never soars. Grahame is the inheritor of the stately style of Thomas Browne and the lyrical effusions of Wordsworth, with a little Dickens and P.G. Wodehouse thrown in as ballast.

Both Kamiya and Jacobs describe their first encounters with the book and how deeply it impacted them. For Kamiay it was as a 14-year-old:

There are certain books that become a permanent part of your life, like an old tree that stands at the bend of a favorite path. You may not notice them, but if they were taken away, the world would be less mysterious, less friendly, less itself.

"The Wind in the Willows" . . . is one of those books. I first read Kenneth Grahame's classic when I was 14, and I have been going back to it ever since. I just read it again, and its wonders seem greater than ever, its colors more glowing, its language more miraculous. Although it is uniquely mixed in style and matter, moving effortlessly from deadpan observation to piercing lyricism to raucous comedy to incantatory mysticism, it is a complete world. And like the old friend that it is, it always welcomes you back.

For Jacobs, it was as an adult:

Best of all were those winter evenings when I crawled into bed and grinned a big grin as I picked up our lovely hardcover edition of Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows, with illustrations by Michael Hague. Before I cracked it open I knew I would like it, but I really never expected to be transported, as, evening by evening, I was. After the first night (I read only one chapter at a stretch), I wanted the experience to last as long as I could possibly drag it out. It was with a sigh compounded of pleasure and regret and satisfaction in Toad's successful homecoming that I closed the book. I knew I would read The Wind in the Willows many times, but I could never again read it for the first time.

September 16, 2011

The Problem of "Angry Calvinists"

There's a part of me that's hesitant to keep banging the drum on the issue of "angry Calvinists."

There's a part of me that's hesitant to keep banging the drum on the issue of "angry Calvinists."

I'm an evangelical Calvinist—but I'm not mad about it, and my friends and role models in these theological circles aren't mean-spirited or angry. So on the one hand it feels something like a stereotype. If 10,000 people read a blog and two cranky Calvinists write a number of comments, some will cluck their tongue and conclude "there go those angry Calvinists."

Furthermore, even if a Calvinist writes with tears, a humble heart, and genuine concern that a certain position is heterodox or dangerous for the church, he can expect to hear the labels like "old guard," "obsessive," "reactionary," "highly rationalistic," "rigid" "naysayers" with a "scholastic spirit" who love nothing more than "gatekeeping," "control[ling] the switches," and "patrol[ling] the boundaries" (actual quotes from an essay).

And, it's tempting to point out that Calvinists don't have a corner on the ugly side of the blogosphere. Wade into some of the posts and comments from other traditions talking about ultimate things and you will see that every "tribe" has their cranks who can be mocking, rude, sarcastic, and nasty. Yet for various reasons people associate and expect anger with Calvinism, making the explicit connection more readily.

But none of that is to deny that there is a problem. Angry Calvinists are not like unicorns, dreamed up in some fantasy. They really do exist. And the stereotype exists for a reason. I remember (with shame) answering a question during college from a girl who was crying about the doctrine of election and what it might mean for a relative and my response was to ask everyone in the room turn to Romans 9. Right text, but it was the wrong time.

This raises an important qualifier. The "angry" adjective might apply to some folks, but it can also obscure the problem. In the example above, I wasn't angry with that girl. I wasn't trying to be a jerk. But I failed to recognize what is "fitting" or necessary (cf. Eph. 4:29) in the moment. This is the sort of thing that tends to be "caught" rather than "taught" and can be difficult to explain. But there's a way to be uncompromising with truth and to be winsome, humble, meek, wise, sensitive, gracious. There's a way of "speaking the truth in love" (Eph. 4:15) such that our doctrines are "adorned" (Titus 2:10) and our words are "seasoned" with salt and grace (Col. 4:6). To repeat, the category of "anger" is often too broad and can miss the mark. As Kevin DeYoung pointed out to me, "Some Calvinists are angry, proud, belligerent people who find Calvinism to be a very good way to be angry, proud, and belligerent. Other Calvinists are immature—they don't understand other people's struggles, they haven't been mellowed by life in a good way, they can only see arguments and not people. The two groups can be the same, but not always."

All of this prompts two questions: (1) why is this the case?, and (2) what can be done about it?

John Piper once offered some reflections on why Calvinists tend at times to be more negative.

I love the doctrines of grace with all my heart, and I think they are pride-shattering, humbling, and love-producing doctrines. But I think there is an attractiveness about them to some people, in large matter, because of their intellectual rigor. They are powerfully coherent doctrines, and certain kinds of minds are drawn to that. And those kinds of minds tend to be argumentative.

So the intellectual appeal of the system of Calvinism draws a certain kind of intellectual person, and that type of person doesn't tend to be the most warm, fuzzy, and tender. Therefore this type of person has a greater danger of being hostile, gruff, abrupt, insensitive, or intellectualistic.

I'll just confess that. It's a sad and terrible thing that that's the case. Some of this type aren't even Christians, I think. You can embrace a system of theology and not even be born again.

Another reason for Calvinists could be seen as negative is that when a person comes to see the doctrines of grace in the Bible, he is often amazed that he missed it, and he can sometimes become angry. He can become angry that he grew up in a church or home where they never talked about what is really there in Romans 8, 1 Corinthians 2, and Ephesians 2. They never talked about it—they skipped it—and he is angry that he was misled for so long.

That's sad. It's there; it's real; the church did let him down, and there are thousands of churches that ignore the truth and don't teach it. And he has to deal with that.

Another reason Calvinists might be perceived as negative is that they are trying to convince others about the doctrines.

If God gives someone the grace to be humbled and see the truth, and the doctrines are sweet to him, and they break his pride—because God chose him owing to nothing in him. He was awakened from the dead, like being found at the bottom of a lake and God, at the cost of his Son's life, brings him up from the bottom, does CPR, brings him miraculously back to life, and he stands on the beach thrilled with the grace of God—wouldn't he want to persuade people about this?

Do Calvinists want to make everybody else Calvinists? Absolutely we do! But it's not about elitism. It's about having been found by Christ and having the glory of God opened to us in the process of salvation. It's about having the majesty of God opened in all of his saving and redeeming works, wanting to give him all the glory and all the credit, and cherishing the sovereignty and preciousness of grace in our lives. Why wouldn't we want to share this with people?

If it is perceived as elitist, that is partly owing to our sinfulness in the way we go about it, and partly owing to people's unwillingness to see what is really there in the Bible.

I just want to confess my own sins in how I have often spoken, and I hope and pray that I don't have the reputation of being mainly negative, but mainly positive.

Ed Stetzer recently had an email exchange with Joe Thorn about the issue of "angry Calvinists." Joe offers some astute analysis and offers four good suggestions:

First, I think it would be fruitful for more correction to come from inside our own theological tribe. I'm not saying criticism is inappropriate if it isn't in-house. As the church we should be able to correct one another across denominational and doctrinal divides. But, we should be most critical of ourselves, and I think addressing our own problems from within our own group will generally prove more fruitful.

Second, when addressing the issue of "those angry Calvinists" we need to be careful and not make Calvinism the issue. It's not about Calvinism. The negativity, pride, and finger wagging is not about the Doctrines of Grace, but the heart. So, when we see such things coming from Calvinists we should seek to point out that this attitude is actually incompatible with Calvinism.

Third, I'd encourage people to simply model a better way. Whether you're a Calvinist or not, modeling loving patience over knee-jerk reaction, gracious discernment over assuming the worst about another's words, and gospel-founded brotherhood over needless separation, will wind up having greater influence in the Christian community than simply dropping bombs on each other.

Fourth, I'd encourage others to simply not engage the haters. There are blogs I simply do not read because it doesn't benefit me spiritually. Some people move me to examine myself, look to Jesus, and grow in grace. Others just provoke me to anger. Often times that anger is unrighteous, or even self-righteous. I can become the angry Calvinist doppelgänger to the angry Calvinist I take issue with. Really, the haters are not my problem, I am my own problem. So, I have learned to just stay away from certain places on the internet. I would encourage others to simply not engage people or personalities that aren't helpful.

Building off of the last point, I'd add a convicting point that Tim Keller says in The Prodigal God on Luke 15:28: Jesus "is not a Pharisee about Pharisees; he is not self-righteous about self-righteousness. Nor should we be. He not only loves the wild-living, free-spirited people, but also hardened religious people" (p. 76).

I think we can all work a bit harder, fully aware of which aspect we tend to neglect: "speaking the truth in love" or "speaking the truth in love."

In Sickness and in Health: A Man of His Word

Wise Thoughts on Parenting

Three posts worth reading:

Soren Gordhamer, 5 Lessons for Parenting in the Digital Age"

Technology no longer has boundaries

Know when to cut it off

The difference between preference and addiction

Focus on technology that truly connects us to our kids

Model the balance

Reb Bradley, Homeschool Blindspots

Having Self-Centered Dreams

Raising Family as an Idol

Emphasizing Outward Form

Tending to Judge

Depending on Formulas

Over-Dependence on Authority and Control

Over-Reliance Upon Sheltering

Not Passing On a Pure Faith

Not Cultivating a Loving Relationship With Our Children

Kevin DeYoung, Children and Secondhand Stress

Quoting Bryan Caplan: "Secondhand stress is one of kids' leading grievances."

HT: David Murray

5 Paradigm-Shifting Books

Michael Horton recommends five influential books that can change the way we think and live:

Athanasius, On the Incarnation of the Word

Luther, Lectures on Galatians

Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion

"The Heidelberg Catechism"

Sproul, The Holiness of God

Inerrancy and Infallibility: Truth Claims and Precision

The word inerrant means that something, usually a text, is "without error." The word infallible—in its lexical meaning, though not necessarily in theological discussions due to Rogers and McKim—is technically a stronger word, meaning that the text is not only "without error" but "incapable of error." The historic Christian teaching is that the Bible is both inerrant and infallible. It is without error (inerrant) because it is impossible for it to have errors (infallible).

In his chapter on "The Inerrancy of Scripture" in The Doctrine of the Word of God (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2010), John Frame offers some important distinctions and clarifications on the doctrine. He points out that inerrancy suggests to many the idea of precision, rather than its lexical meaning of mere truth.

Frame points out that "precision" and "truth" overlap in meaning but are not synonymous:

A certain amount of precision is often required for truth, but that amount varies from one context to another. In mathematics and science, truth often requires considerable precision. If a student says that 6+5=10, he has not told the truth. He has committed an error. If a scientist makes a measurement varying by .0004 cm of an actual length, he may describe that as an "error," as in the phrase "margin of error."

Frame then reminds us that truth and precision are usually more distinct when we move outside the fields of mathematics and science:

If you ask someone's age, the person's conventional response (at least if the questioner is entitled to such information!) is to tell how old he was on his most recent birthday. But this is, of course, imprecise. It would be more precise to tell one's age down to the day, hour, minute, and second. However, would that convey more truth? And, if one fails to give that much precision, has he made an error? I think not, as we use the terms truth and error in ordinary language. If someone seeks to tell his age down to the second, we usually say that he has told us more than we want to know. The question, "What is your age?" does not demand that level of precision. Indeed, when someone gives excess information in an attempt to be more precise, he actually frustrates the process of communication, hindering rather than communicating truth. He buries his real age under a torrent of irrelevant words.

Similarly, when I stand before a class and a student asks me how large the textbook is. Say that I reply "400 pages," but the actual length is 398. Have I committed an error, or told the truth? I think the latter, for the following reasons: (a) In context, nobody expects more precision than I gave in my answer. I met all the legitimate demands of the questioner. (b) "400," in this example, actually conveyed more truth than "398″ would have. "398″ most likely would have left the student with the impression of some number around 300, but "400″ presented the size of the book more accurately.

The relationship between "precision" and "error," Frame says, is actually more complicated than many recognize. "What is an error?" sounds like a simple question with an easy-to-find answer. But "identifying an error requires some understanding of the linguistic context, and that in turn requires an understanding of the cultural context."

A child who says in his math class that 6+5=10 may not expect the same tolerance as a person who gives a rough estimate of his age or a professor who exaggerates the size of a book by two pages.

We should always remember that Scripture is, for the most part, ordinary language rather than technical language. Certainly, it is not of the modern scientific genre. In Scripture, God intends to speak to everybody. To do that most efficiently, he (through the human writers) engages in all the shortcuts that we commonly use among ourselves to facilitate conversation: imprecisions, metaphors, hyperbole, parables, etc. Not all of these convey literal truth, or truth with a precision expected in specialized contexts; but they all convey truth, and in the Bible there is no reason to charge them with error.

How then does inerrancy relate to precision? Frame suggests "sufficient precision" as opposed to "maximal precision."

Inerrancy, therefore, means that the Bible is true, not that it is maximally precise. To the extent that precision is necessary for truth, the Bible is sufficiently precise. But it does not always have the amount of precision that some readers demand of it. It has a level of precision sufficient for its own purposes, not for the purposes for which some readers might employ it.

Frame then introduces an important aspect of propositional language: it "makes claims on its hearers":

When I say that the book is on the table, I am claiming that in fact the book is there. If you look, you will find it, precisely there. But if I say that I am age 24 (do I wish!), I am not claiming that I am precisely 24. I am claiming, rather, that I became 24 on my last birthday. Moreover, if I say, as in the previous example, that there are 400 pages in a textbook, I am not claiming that there is precisely that number of pages, only that the number 400 gives a pretty reliable estimate of the size of the book. Of course, if I worked for a publisher, and gave him an estimate of the size of the book that was two pages off, I could cost him a lot of money and myself a job. In that context, my imprecision would certainly be called an error. However, in the illustration of the professor making an estimate before his class, it would have been inappropriate to say that he was in error. Even though I use the same language in the two situations, I am making a different claim in the first situation from the claim I make in the second. Therefore, the amount of precision demanded and expected in one case is different from what is demanded and expected in the other. In the one case, I have made an error; in the other case not.

Frame points out that a "claim" in this sense can be explicit or implicit.

If someone asks me to quote a Bible passage, and I say "this is inexact," I am making an explicit claim, namely, "I will give you the gist of it, but not the exact words." Nevertheless, it is rare in language for someone to make his claims explicit in that way. When a person gives his age, he rarely says, "I am giving you an approximate figure." Rather, he simply accepts the custom of approximating one's age by the last birthday, assuming that people will understand that custom and will not be misled into thinking that his answer is absolutely precise. In following this custom, people understand that he is making an implicit claim.

Frame applies this principle to the biblical language and world:

So, in reading the Bible, it is important to know enough about the language and culture of the people to know what claims the original characters and writers were likely making. When Jesus tells parables, he does not always say explicitly that his words are parabolic. But his audience understood what he was doing, and we should as well. A parable does not claim historical accuracy, but it claims to set forth a significant truth by means of a likely nonhistorical narrative.

This leads to Frame's definition of inerrancy:

So, I think it is helpful to define inerrancy more precisely (!) by saying that inerrant language makes good on its claims. When we say that the Bible is inerrant, we mean that the Bible makes good on its claims.

Now many writers have enumerated what are sometimes called qualifications to inerrancy: inerrancy is compatible with unrefined grammar, non-chronological narrative, round numbers, imprecise quotations, pre-scientific phenomenalistic description (e.g., "the sun rose"), use of figures and symbols, imprecise descriptions (as Mark 1:5, which says that everyone from Judea and Jerusalem went to hear John the Baptist). I agree with these points, but I do not describe them as "qualifications" of inerrancy. These are merely applications of the basic meaning of inerrancy: that it asserts truth, not precision. Inerrant language is language that makes good on its own claims, not on claims that are made for it by thoughtless readers.

September 15, 2011

The Gospel-Emptying Cruelty of Pat Robertson

Sometimes I think the category of "righteous anger" was created to respond to people like Pat Robertson.

His latest cringe-inducing statement is that a man should divorce his wife suffering with Alzheimer's disease and "start all over again" if he is lonely and in need of companionship. When asked about the vow "to death due us part," Robertson responded that "if you respect that vow," then Alzheimer's can be viewed as "a kind of a death."

The best counsel is usually to ignore Robertson. But when a professing Christian says such cruel and worldly things, it also presents an opportunity to reexamine gospel truth afresh. In that regard Russell Moore has provided a wonderful service for us. He rightly writes that Robertson's statement "is more than an embarrassment. This is more than cruelty. This is a repudiation of the gospel of Jesus Christ."

At the arrest of Christ, his Bride, the church, forgot who she was, and denied who he was. He didn't divorce her. He didn't leave.

The Bride of Christ fled his side, and went back to their old ways of life. When Jesus came to them after the resurrection, the church was about the very thing they were doing when Jesus found them in the first place: out on the boats with their nets. Jesus didn't leave. He stood by his words, stood by his Bride, even to the Place of the Skull, and beyond.

A woman or a man with Alzheimer's can't do anything for you. There's no romance, no sex, no partnership, not even companionship. That's just the point. Because marriage is a Christ/church icon, a man loves his wife as his own flesh. He cannot sever her off from him simply because she isn't "useful" anymore.

Pat Robertson's cruel marriage statement is no anomaly. He and his cohorts have given us for years a prosperity gospel with more in common with an Asherah pole than a cross. They have given us a politicized Christianity that uses churches to "mobilize" voters rather than to stand prophetically outside the power structures as a witness for the gospel.

But Jesus didn't die for a Christian Coalition; he died for a church. And the church, across the ages, isn't significant because of her size or influence. She is weak, helpless, and spattered in blood. He is faithful to us anyway.

If our churches are to survive, we must repudiate this Canaanite mammonocracy that so often speaks for us. But, beyond that, we must train up a new generation to see the gospel embedded in fidelity, a fidelity that is cruciform.

You can keep reading the whole thing here.

To see the gospel-centered perspective in action and in contrast, listen to or read the story of Robertson McQuilkin's commitment to his wife Muriel.

10 Essential Classics of Western Literature

John Mark Reynolds, founder of a Great Books program and editor of The Great Books Reader, writes at TGC on 10 classics of western lit that shaped his life:

Here are 10 books that began the rebirth in my own soul of something better. Eccentric though such a list must be it at least has the benefit of actually having helped one person and I have some hope that where it helped one it may help another.

I have limited myself to one sentence to say why I read them. It is so little to say that nobody will be tempted to think I have captured the essence of any of these books. I have also eliminated works Christians are likely to know to read. If you have not read the entire Institutes or Augustine's Confessions, you are not a literate Christian whatever your piety, and you already understand this fact.

Instead, I hope to motivate you to begin, just begin, to participate in a great conversation about these ideas that will last, I trust, for all eternity.

You can read the list here.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers