Justin Taylor's Blog, page 28

December 31, 2018

Martin Luther’s Personal Letter to a Close Friend Struggling with Spiritual Despair

The following is from a letter written in July 1530 to Jerome Weller, a 31-year-old friend who had previously lived in the Luther home, tutored his children, and was now struggling with spiritual despair:

. . Excellent Jerome, You ought to rejoice in this temptation of the devil because it is a certain sign that God is propitious and merciful to you.

You say that the temptation is heavier than you can bear, and that you fear that it will so break and beat you down as to drive you to despair and blasphemy.

I know this wile of the devil. If he cannot break a person with his first attack, he tries by persevering to wear him out and weaken him until the person falls and confesses himself beaten.

Whenever this temptation comes to you, avoid entering upon a disputation with the devil and do not allow yourself to dwell on those deadly thoughts, for to do so is nothing short of yielding to the devil and letting him have his way.

Try as hard as you can to despise those thoughts which are induced by the devil. In this sort of temptation and struggle, contempt is the best and easiest method of winning over the devil.

Laugh your adversary to scorn and ask who it is with whom you are talking.

By all means flee solitude, for the devil watches and lies in wait for you most of all when you are alone. This devil is conquered by mocking and despising him, not by resisting and arguing with him. . . .

When the devil throws our sins up to us and declares we deserve death and hell, we ought to speak thus:

“I admit that I deserve death and hell.

What of it?

Does this mean that I shall be sentenced to eternal damnation?

By no means.

For I know One who suffered and made a satisfaction in my behalf.

His name is Jesus Christ, the Son of God.

Where he is, there I shall be also.”

Yours,

Martin Luther

Martin Luther, Letters of Spiritual Counsel, trans. and ed. Theodore G. Tappert (orig., 1960; reprint, Vancouver, BC: Regent College Publishing, 2003), 84–87.

December 16, 2018

An Interview with Dallas Jenkins on the First Multi-Season Drama about the Life of Christ

I recently caught up with the talented filmmaker Dallas Jenkins, who has just wrapped up shooting the first several episodes of a show that I think readers will be very interested in. Here was our conversation, followed by the pilot episode.

For those who haven’t heard yet, what is “The Chosen“?

“The Chosen” is the first ever multi-season drama about the life of Christ. There’s been movies and mini-series, but never a binge-watchable show where you can really invest in the characters. We also focus a lot on the characters Jesus encountered, giving them and their stories fresh life and backstory.

Can you tell us a bit of background about how this all came about?

It actually came out of failure.

My last feature film, The Resurrection of Gavin Stone, did poorly at the box office, and the Hollywood companies I’d partnered with backed out of future plans to do more.

I honestly didn’t know if I had a future in films.

So I focused on an idea I’d had about the birth of Christ from the perspective of the shepherds.

I made a short film for my church’s Christmas Eve service, and while I was doing it, it was clear this was where I should be. And I thought, “What about a show? Why hasn’t that been done before?”

Long story short, the short film was seen by a streaming service, they flipped out and loved the idea of the show, and the short film [below] went viral online.

It’s now got about 20 million views in ten languages around the world.

What are some of the challenges in producing something that is simultaneously fresh (given how many other films have been done on it) and faithful (given the limited historical data to work with)?

The challenge is in the original decision to do this. Do we believe it’s okay to tell Bible stories and fill in all those gaps with historical data and artistic imagination? Some people don’t. We do (obviously).

I’m a Bible-believing evangelical, I have zero desire to mess with Scripture or make some sort of new theological point. This is about telling these stories in a way that makes the moments in Scripture even more impactful.

For example, when a good pastor preaches about a gospel story and gives you the historical context and expounds on the personalities of the people involved, it puts you there. And I’ve had so many emotional moments thinking, “That person is me.”

Joni Earecksen Tada, after seeing the Christmas special episode and sobbing, said, “Thank you for telling the old, old story in an impossible fresh way.” That’s my goal. And I believe we can do that by showing Jesus to the audience through the eyes of those he surrounded himself with.

The challenge comes in making sure we do it right. We’ve chosen a New Testament scholar and a Messianic Jewish rabbi as our primary consultants, both of them conservative theologians and historians.

You have partnered with VidAngel to produce this. Who are they and why did you guys decide to link up?

VidAngel is a steaming service primarily known for filtering. Basically, you watch Netflix and Amazon shows through their service and you can literally filter out whatever you find offensive. What’s cool is that it’s in your hands, you choose. So my younger kids can now watch Stranger Things on Netflix with us because we filtered out the language and blasphemy.

They’re wanting this to be their big new piece of original content.

We’re with them for two primary reasons:

One, it was their idea to finance this through crowd-funding, an idea I laughed at at first. But their efforts have led to $6 million so far. We’re already the number one highest crowd-funded media project in history.

Two, they believe in this project and want this show to impact the world; plus, they’re giving us complete control of the content. That wouldn’t happen anywhere else.

You guys have devised a unique crowdfunding platform for this project that actually is a form of investment. How’s it going so far? How can folks get involved?

Most crowd-funding efforts involve people donating and getting something like a t-shirt or name in credits. Which is fine. But VidAngel’s approach is partnership. This is investment. If the show succeeds, you succeed.

Of course, most of our investors are doing this for Kingdom purposes, as we are. And if you want to just keep investing back into the show so we can expand our impact, that’s awesome. But that’s your choice. Either way, we’re all providing our loaves and fishes, and we’ll watch Jesus feed the five thousand.

So what’s next? And how can readers pray about the project if they feel so led?

We are currently working on the first four episodes. We still have a lot of fundraising to do. We need finances for writing the rest of season one, and of course for marketing so we can get this show around the world. But if people aren’t interested in partnering with us financially, we just ask two things.

One, watch and share the special Christmas episode [below]. We believe if people can see Jesus through the eyes of those who encountered him, they can be impacted in the same way.

And two, pray that we remain humbled and broken throughout this project so that we are letting God tell his story and not getting in the way. I don’t want my own bias or vision to impede what He’s doing. So far, so good.

December 14, 2018

If They Weren’t Taking Notes, How Did the Disciples Remember Jesus’s Exact Teaching? The 3-Step Process for Formulating the 4 Gospels

Brant Pitre’s The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ is creative and compelling. Read along with Peter Williams’s Can We Trust the Gospels? readers will have an outstanding one-two punch.

Pitre includes a helpful summary of how oral tradition, memory, and discipleship played into the formation of the Gospels.

Stage 1. The Life and Teaching of Jesus

As a Jewish “rabbi” (rabbi), Jesus “taught” (didaskō) his “students” (mathētai) in the context of a rabbi-student relationship. His students lived with him and learned from him for some three years.

During this time, Jesus expected his students to “remember” (mnēmoneuō) what he said and instructed them to begin “teaching” (didaskō) others while he was still alive (see Mark 4:1-20; 6:1-13, 30; 8:18; 9:5; 11:21; and parallels).

Stage 2. The Preaching of Jesus’s Students

After Jesus’s death, the students of Jesus “remembered” (mnēmoneuō) what he had said and done, and they “taught” (didaskō) others about what they had seen and heard.

Their preaching was based on the skilled memories of trained students and the rehearsed memories of disciples who repeatedly preached about what Jesus said and did (see John 2:22; 12:16; 15:20; 16:4; Acts 4:2-20; 20:35).

Stage 3. The Writing of the Gospels

Eventually, the evangelists “wrote” (graphō) either what they themselves “witnessed” (martyreō) or what was “handed on” (paradidōmi) to them by “eyewitnesses” (autoptai) who were present with Jesus “from the beginning” (see Luke 1:1-4; John 21:24).

Pitre points out that to be a “disciple” is literally to be a student (Greek mathētēs; Hebrew talmid).

Being a student in the ancient world was radically different from what it is like today, when it simply means you may (or may not) listen to a fifty-minute lecture three times a week for a semester. Being one of Jesus’s students meant following him everywhere, and listening to him all the time, for anywhere between one and three years. As the Gospels make clear, it also meant remembering what he said (Matthew 16:9; Mark 8:18; John 15:20; 16:4).

He quotes John Meier:

Jesus called individuals to follow him literary, physically, as he undertook various preaching tours of Galilee, Judea and surrounding areas. . . . Following Jesus as his disciple meant leaving behind one’s home, parents, and livelihood. One could not follow Jesus simply by staying at home and studying his teachings or by going to his school-house and attending his lectures.

In another section he shows that there is virtually no evidence for the common claim that the Gospels were originally anonymous. But if we take seriously the evidence for their apostolic origin, it means one of two things:

They either contain the memories of Jesus’s students (the Gospels of Matthew and John) or are based on the memories of Jesus’s students that were passed on to their followers (such as Mark’s record of Peter’s preaching). Even Luke’s Gospel claims to be based on the testimony of those who were eyewitnesses “from the beginning” of Jesus’s public ministry (Luke 1:1).

He continues:

Notice how different this is from the now widespread theory that our information about Jesus is primarily based on decade after decade of anonymous storytelling. Of course uncontrolled stories about Jesus circulated; the Gospel of Luke even mentions anonymous “reports” (Greek ēchos) making the rounds during Jesus’s lifetime (Luke 4:37).

However, as I have argued in earlier chapters, that’s not what the four Gospels claim to be. They are not the last links in a long chain of anonymous rumors and stories. They are ancient biographies and authoritative accounts of the life of Jesus based on the testimony of his students. As such, they function in part precisely as controls over what was being said about Jesus.

He also highlights the fact that the disciples would have frequently rehearsed their memories, starting in Jesus’s lifetime. He quotes Richard Bauckham, “Frequent recall is an important factor in both retaining the memory and retaining it accurately,” and comments:

Anyone who is a teacher knows this to be true. I might not be able to tell you what I did last week, but I could give you a three-hour lecture about Jesus and the Jewish roots of the Last Supper with zero preparation because I have been talking about it all the time for the last ten years. That’s one key difference between rehearsed memories and incidental memories.

Pitre’s point is not about inspiration per se, but rather about the historical and cultural practice of moving from the original events to the written records.

For how divine inspiration relates to all of this, I have found J. I. Packer’s work to be clear and clarifying:

[For] the didactic inspiration of the biblical historians, wisdom teachers, and New Testament apostles. . . . the effect of inspiration was that after observation, research, reflection, and pray they knew just what they should say in God’s name, as witnesses and interpreters of His work. . . .

God so controlled the process of communication to and through His servants that, in the last analysis, He is the source and speaker . . .

Whether spoken viva voce or written, and whether dualistic or didactic or lyric in its psychological mode, inspiration—that divine combination of prompting and control that secures precise communication of God’s mind by God’s messenger—remains theologically the same thing. (Packer, “The Adequacy of Human Language,” in Inerrancy, ed. Normal L. Geisler [Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1980], pp. 198, 199.

Stop Saying 81 Percent of White Evangelicals Vote for Trump (It Was Probably Less Than Half)

I know I’m fighting a losing battle with this post. It won’t go viral. It probably won’t change many minds.

But I’ll give it a shot anyway.

No matter how many times people make the claim, it is simply wrong to say that 81 percent of white evangelicals in the United States voted for Donald Trump to become president.

First (and I know this is quibbling), the number that people are meaning to cite is actually 80 percent.

(Media originally reported 81 percent, but that was based on initial reports of the exit poll before the tabulations were complete.)

Second, the statistic was not purporting to measure the total percentage of all white self-identified evangelicals.

Rather, the number is supposed to indicate the number of white voters who self-identify as born-again or evangelicals and voted for Trump.

That sounds like mere semantics, but it actually represents a significant difference. Evangelical historian Thomas Kidd uses recent statistical analysis to estimate that 40 percent of white evangelicals didn’t vote in this election (see, e.g., this).

If we then grant the 80 percent figure for the remaining 60 percent who did vote ended up casting their ballot for Trump, then it would be the case that less than half (48 percent) of white self-identified evangelicals voted for Donald Trump.

Third, we know almost nothing about the 80 percent beyond a religious label they affirm or an experience they claim.

Do they go to church? Are they Protestant? Unless we are willing to say that “an evangelical is anyone who says he or she is an evangelical or says he or she has been ‘born again,'” then we have to admit that we are talking more about a label of self-designation than an actual movement or network, much less a reflection of theological belief or religious practice.

For example, an array of theological traditions outside of the traditional evangelical movement have adherents who say they are “evangelical” or have been “born again,” including:

mainline Protestants (27 percent)

Roman Catholics (22 percent)

Orthodox (18 percent)

Mormons (23 percent)

Jehovah’s Witness (24 percent)

spiritualist Christians (24 percent)

[As an aside: some people rightly point out that 35 percent of those who self-identify as evangelical are minorities:

19 percent black

10 percent Hispanic,

6 percent combination of Asian, mixed race, or other ethnicities

But the 80 percent number was specifically limited to white voters who self-identify as evangelical/born again, not to all who identify with these religious markers.]

Finally, it is reasonable to estimate that less than half of the 80 percent actually hold to traditional evangelical beliefs.

As researchers have discovered serious limitations in how to identify and measure evangelicals beyond the exit-poll data that merely asks this as a yes-or-no self-identification question, more sophisticated polling data has recently been used, revealing that fewer than half (45 percent of respondents) who self-identify as evangelical strongly hold to evangelical beliefs as articulated by the Bebbington Quadrilaterial (with its emphases on conversionism, biblicism, activism, and crucicentrism).

This is not a defense of evangelicals and their relationship to Donald Trump. (I have been a critic regarding that relationship, especially with regard to what historian John Fea calls the Court Evangelical leaders who serve as his acolytes.) This says nothing about what his current level of support may or may not be. It’s simply a little plea for more accuracy about how we describe the role of evangelicals in the 2016 election. Criticize them all you want—but let’s first define our terms and strive for accuracy.

December 12, 2018

‘Much of the Story Has Never Been Told’: Slavery and Racism in the History of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

Albert Mohler, president of the The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, has written a letter introducing a historic report being released by the school, completing a year-long investigation into and reckoning with their own institutional history with respect to racism and slavery.

Here is an excerpt:

A year ago, I asked a team of Southern Seminary and Boyce College faculty members to spend twelve months conducting a thorough investigation of these questions. Some of our own students were asking these questions. We all should have been asking these questions. How can a school like Princeton University face the truth while we, holding to the truth of the gospel, would refuse to do the same?

The chairman was Dr. Gregory A. Wills, professor of church history and former dean of the School of Theology. Author of our sesquicentennial history, published by Oxford University Press, and a skilled historian, Dr. Wills convened the meetings and wrote the draft of the report. Others serving with him include Dr. Jarvis J. Williams, associate professor of New Testament interpretation; Dr. Curtis A. Woods, assistant professor of applied theology and biblical spirituality and associate executive director of the Kentucky Baptist Convention; Dr. Matthew J. Hall, dean of Boyce College; Dr. John D. Wilsey, associate professor of church history; and Dr. Kevin Jones, associate dean of Boyce College at the time of commissioning and now interim chair of the School of Education and Human Development at Kentucky State University. To each of them we owe a great debt. Their year of labor is now an important contribution to Southern Seminary’s history.

With this letter, I release this entire report to the public. Nothing has been withheld. At the onset, I made a pledge to this team that I would hold nothing from the public and would release their report in full.

What does all of this mean? We are faced with very hard questions, but they are not new to historic Christianity. When I arrived as a student at the Seminary in 1980, I came ready to make the history of this school my history, even as the history of the Southern Baptist Convention is my history. Over time, I had to think some hard thoughts. How could Christians hold, simultaneously, such right and wrong beliefs? How could a heroic figure like Martin Luther, that great paragon of the Reformation, teach, defend, and define the glorious truths of the gospel while expressing vile medieval anti-Semitism? The questions come again and again.

Eventually, the questions come home. How could our founders, James P. Boyce, John Broadus, Basil Manly Jr., and William Williams, serve as such defenders of biblical truth, the gospel of Jesus Christ, and the confessional convictions of this Seminary, and at the same time own human beings as slaves—based on an ideology of race—and defend American slavery as an institution?

Like Luther, they were creatures of their own time and social imagination, to be sure. But this does not excuse them, nor will it excuse us. The very confessional convictions they bequeathed to us reveal that there is only one standard by which Christians must make such judgments, and that is the sole authority of the Bible. They preached the gospel of Jesus Christ to all people, slave and free. We hold to that same gospel, pointing sinners to the promise of salvation through faith in Jesus Christ. Like our founders, we believe that repentance, which they confessed as an “evangelical grace,” is essential to the gospel. The very gospel truths that they taught, defined, and handed down to us are the very truths that allow us to release this report with both lament and conviction.

We must repent of our own sins, we cannot repent for the dead. We must, however, offer full lament for a legacy we inherit, and a story that is now ours. But this report is not the shattering of images. Boyce, Broadus, Manly, and Williams would be first to make that clear. As Christians, we know no total sanctification or perfection in this life. We await something better, our future glorification by Christ.

We also rejoice in knowing that Christ is creating a new humanity, purchased with his precious blood. Thanks be to God, we are seeing the promise of that new humanity, right here on the campus of Southern Seminary and Boyce College. Right here, right now, we see students and faculty representing many races and nations and ethnicities. Our commitment is to see this school, founded in a legacy of slavery, look every day more like the people born anew by the gospel of Jesus Christ, showing Christ’s glory in redeemed sinners drawn from every tongue and tribe and people and nation.

We are particularly humbled by the grace and love of the many African-Americans who are counted among our alumni, students, faculty, and trustees. Our commitment is that this school will honor you, cherish you, and welcome you—everyday, evermore. You are many and you are precious to this school. You are helping us to write the present and the future, by God’s grace and to God’s glory.

In light of the burdens of history, some schools hasten to remove names, announce plans, and declare moral superiority. That is not what I intend to do, nor do I believe that to be what the Southern Baptist Convention or our Board of Trustees would have us to do.

We do not evaluate our Christian forebears from a position of our own moral innocence. Christians know that there is no such innocence. But we must judge, even as we will be judged, by the unchanging Word of God and the deposit of biblical truth.

Consistent with our theology and the demands of truth, we will not attempt to rewrite the past, nor can we unwrite the past. Instead, we will write the truth as best we can know it. We will tell the story in full, and not hide. By God’s grace, we will hold without compromise to the faith once for all delivered to the saints.

The following 13 points constitute a summary of the findings in the 66-page report:

The seminary’s founding faculty all held slaves.

The seminary’s early faculty and trustees defended the righteousness of slaveholding.

Upon Abraham Lincoln’s election, the seminary faculty sought to preserve slavery.

The seminary supported the Confederacy’s cause to preserve slavery.

After emancipation, the seminary faculty opposed racial equality.

In the Reconstruction era, the faculty supported the restoration of white rule in the South.

Joseph E. Brown, the seminary’s most important donor and chairman of its Board of Trustees 1880-1894, earned much of his fortune by the exploitation of mostly black convict-lease laborers.

The seminary faculty urged just and humane treatment for blacks.

Before the 1940s, the seminary faculty generally approved the Lost Cause mythology.

Until the 1940s, the seminary faculty supported black education and the segregation of schools and society.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the seminary faculty appealed to science to support their belief in white superiority.

The seminary admitted blacks to its degree programs in 1940 and integrated its classrooms in 1951.

The seminary faculty supported civil rights for blacks but had mixed appraisals of the Civil Rights Movement.

You can read the entire narrative here.

December 11, 2018

C. S. Lewis on the Enchantment and Disenchantment of Riding a Bicycle

Only C. S. Lewis could take a common experience—the various ways in which we think throughout life about the riding of a bicycle—and use it as an illustration of the four universal phases of life, and how they point above and beyond themselves to something that nothing in this world can satisfy.

In October 1946, in a publication called Resistance, Lewis wrote a short piece called “Talking about Bicycles,” describing a (perhaps fictional) conversation with a friend about the various phases of life as illustrated through his approach to riding a bicycle.

In the excerpt below, I’ve added headings to discuss the time period being described.

[1. Unenchantment]

I can remember a time in early childhood when a bicycle meant nothing to me: it was just part of the huge meaningless background of grown-up gadgets against which life went on.

[2. Enchantment]

Then came a time when to have a bicycle, and to have learned to ride it, and to be at last spinning along on one’s own, early in the morning, under trees, in and out of the shadows, was like entering Paradise. That apparently effortless and frictionless gliding—more like swimming than any other motion, but really most like the discovery of a fifth element—that seemed to have solved the secret of life. Now one would begin to be happy.

[3. Disenchantment]

But, of course, I soon reached the third period. Pedalling to and fro from school (it was one of those journeys that feel up-hill both ways) in all weathers, soon revealed the prose of cycling. The bicycle, itself, became to me what his oar is to a galley slave. . . .

[4. Re-enchantment]

I have had to go back to cycling lately now that there’s no car. And the jobs I use it for are often dull enough. But again and again the mere fact of riding brings back a delicious whiff of memory. I recover the feelings of the second age. What’s more, I see how true they were—how philosophical, even. For it really is a remarkably pleasant motion. To be sure, it is not a recipe for happiness as I then thought. In that sense the second age was a mirage. But a mirage of something. . . . Whether there is, or whether there is not, in this world or in any other, the kind of happiness which one’s first experiences of cycling seemed to promise, still, on any view, it is something to have had the idea of it. The value of the thing promised remains even if that particular promise was false—even if all possible promises of it are false.

Lewis’s “friend” (who sounds a lot like Lewis!) goes on to apply this to several areas of life, including love:

We all remember the Unenchanted Age—there was a time when women meant nothing to us.

Then we fell in love; that, of course, was Enchantment.

Then, in the early or middle years of marriage there came—well, Disenchantment. All the promises had turned out, in a way, false. No woman could be expected—the thing was impossible. . . .

I don’t think I could explain to a bachelor how there comes a time when you look back on that first mirage, perfectly well aware that it was a mirage, and yet, selling all the things that have come out of it, things the boy and girl could never have dreamed of, and feeling also that to remember it is, in a sense, to bring it back in reality, so that under all the other experiences it is still there like a shell lying at the bottom of a clear, deep pool—and that nothing would have happened at all without it—so that even where it was least true it was telling you important truths in the only form you would then understand.

You can find the whole essay in Lewis’s book Present Concerns.

December 4, 2018

How Liberal New Testament Scholarship Is Being Left Behind

Craig Blomberg, New Testament Theology, pp. 5–6:

Particularly noteworthy is how little attention is paid in more liberal circles (even more so in the United States today than in Germany!) to the growing body of literature spawned in varying ways by Larry Hurtado and Richard Bauckham, which has demonstrated that a high, divine Christology was pervasively present throughout the earliest church in ways that are best explained as the vindication of the very claims and ministry of Jesus himself.

So much of the parceling out of the various books of the NT to the last decades of the first and even the early second centuries depends on the perception of various forms of evolutionary trajectories of theological development and vice versa.

The scholarship in this tradition can easily get caught up in a hermeneutical circle without realizing it.

Why do we date a certain book later than early Christian tradition uniformly did (and therefore determine it to be pseudonymous)?

Because it contains theology that developed only at a later point.

How do we know that it developed only at a later date (and therefore that the books that contain it have to be pseudonymous)?

Because it contains later theology!

The possibility of revolutionary developments occurring very quickly after Jesus’ death, if not entirely discounted, is at the most given very limited attention.

And assumptions about pseudonymity continue to be taken as demonstrated, despite increasingly numerous rebuttals both to the concept being acceptable in early Christianity in general and to the reasons for applying it to individual NT documents.

Along these lines, Blomberg cites the following works that liberal NT scholarship has failed to catch up with:

Larry W. Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity

Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the God of Israel: God Crucified and Other Studies on the New Testament’s Christology of Divine Identity

Terry L. Wilder, Pseudonymity, the New Testament, and Deception: An Inquiry into Intention and Reception

Jeremy N. Duff, “A Reconsideration of Pseudepigraphy in Early Christianity” (D.Phil. thesis, Oxford University, 2008).

December 3, 2018

Songs of Common Prayer: An Interview with Greg LaFollette

Greg LaFollette is a musician and producer in Nashville, Tennessee. He is the resident artist at a local church plant, Grace Story Church, and serves as their director of arts and liturgy.

His sophomore album, Songs of Common Prayer, featuring artists Sara Groves, Sarah Masen, and Taylor Leonhardt, was recently released, and I caught up with him to ask a few questions about it and to share some samples.

The lyrics for this album are either taken directly from or inspired by the Book of Common Prayer. Some readers won’t know what that is. Can you explain?

The Book of Common Prayer, written and compiled in the 16th century by Thomas Cranmer, was a centerpiece in the decades following the English Reformation and is still used widely across many denominations all around the world.

It offers a structure for corporate worship services as well as daily devotion and structured Bible reading.

Its prayers are affecting and beautiful. Here’s an example:

Almighty and eternal God, so draw our hearts to you,

So guide our minds, so fill our imaginations, so control our wills,

That we may be wholly yours, utterly dedicated unto you;

And then use us, we pray you, as you will,

And always to your glory and the welfare of your people;

Through our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.

Amen.

Is there a tradition within Anglicanism of taking the liturgy and turning it into song?

I think so. The church has always set her prayers and confessions to music. In creating Songs of Common Prayer, I wanted to join the cloud of witnesses who have contributed art to the Church for the purpose of bringing people together in worship.

I have a bunch of Eagles and Steely Dan songs that I just know. I didn’t try to learn them, I just did. They come on the radio and I sing along . . . somehow. I wrote this album with that formational intention in mind, pairing the Book of Common Prayer’s time-honored poetry (which is often taken from the lavish language of Scripture) with melodies that can be embodied, lived into, and passed on to future generations.

You are currently serving as the director of arts and liturgy in a Baptist church plant. In what ways do you see Baptists increasingly open to the beauty and power of the liturgical tradition?

A friend was just telling me about a Baptist church where, during the Scripture reading, the reader of the Gospel processes down from the stage and walks into the middle of the sanctuary where the people turn and reorient themselves to hear the words. This liturgical act mirrors Jesus’s incarnation: emptying himself and coming to dwell among his people. After growing up in a Baptist church, this sort of intention and symbolism makes a meaningful impact on me.

At Grace Story Church we incorporate many of these liturgical practices into our weekly gatherings. We often sing the Lord’s Prayer, and every week we recite the Apostles’ Creed and confess our sin corporately following the sermon. These communal actions remind us that we are not alone in our faith. We as individuals are not alone, and we as a small church plant are not alone.

One of the primary issues with liturgy is that it can become rote and uninhabited, and it is important to remain vigilant around that danger. But there is also a great benefit to constancy and declaring things to be true even when they don’t seem like they are or we don’t feel like it. Liturgy allows us to bring our honest emotions, true desires, and ordinary offerings to God while enjoying the freedom of its inherent boundaries. It can bring us closer to authenticity in worship; and that’s what I find people to be open to—real, authentic, intimate relationship with God.

What was the the most meaningful song on the album to write?

I wrote a song called “We Cry Mercy” that features Sara Groves. It’s a simple lyric with a call and response treatment.

“Lord, have mercy. Christ, have mercy. O Lord, have mercy on us. We cry mercy.”

That’s it.

I wrote this song for the person who shows up at church in frustration, confusion, or pain; who feels like all they can genuinely offer God is lip service. I sing this song as someone who has exhausted his capabilities to manage life and is desperately hoping that God is real and that what the Bible says about his love is true.

I wept as I performed this song, considering my suffering and asking God to take it easy on me—to give me a break. With the psalmists before me, I want to create safe spaces for those who might feel similarly; places where honesty and vulnerability will invite communion and healing; the ground where relationship deepens.

As you have dreamed and labored on this album, and now that it is available, in what ways do you pray and envision churches and individual Christians using and benefiting from this beautiful album?

I pray these songs will be a reminder that what unites us is greater than what divides us; that every denominational difference is not an insurmountable division. I hope that, even as we hold steadfastly to right doctrine, perfect love would drive out fear, and we would enjoy greater unity in the church.

I pray that Songs of Common Prayer would cause us to slow down and open our hands to receive and accept reality; open our hearts to trust and worship God; and open our eyes to our brothers and sisters beside, behind, and before us.

Last, I want to inspire the Church toward rich, intimate relationship with God.

For readers who want to sample and purchase the songs, where can they go?

They can click here to listen.

Nyk + Cali Wedding Photography

Nyk + Cali Wedding Photography

November 28, 2018

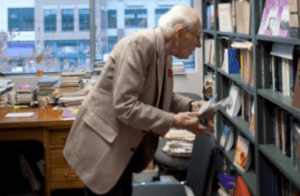

Why J. I. Packer Reads Mystery Novels (Or, In Defense of Light Reading)

A well-read public figure was recently asked about what modern fiction he reads, and he replied that he only makes time for older fiction in his life right now—books that have stood the test of time. Not surprisingly, his preference was criticized. One person even claimed that this choice was a failure of neighbor love (despite the fact that the figure is actively involved in his own community).

Alan Jacobs, in his book on The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction, pushes against this line of thinking when he urges us to “read at whim.” In a CT interview, John Wilson asked him about the background to this counsel:

Where this really got started was with the many, many students who have come to me over the years after graduating from Wheaton. And they think, Oh, there are so many important books I haven’t read. They come to many teachers, but I get my fair share of them. They come to me and say, “Give me 10 books that I should read over the next year.” Or: “Give me 10 books that you think everyone should read.” I always find myself thinking, Read what you want to read. Since you were 6 years old you’ve been reading things that people told you to read. Now you don’t have to do that anymore, unless you’re going to graduate school. Go out and read what strikes you as being fun.

I don’t think these students trust themselves to be readers on their own. They want to continue the sort of reading under direction that they have experienced ever since they started school. Over the years I’ve gotten absolutely stiff-necked about it. I refuse to give any recommendations. I say, “Go and read for fun,” because that sense of reading as a duty is not going to carry you through. It’s not going to sustain you as a vibrant reader, as you will be if you read what gives you delight. You may have actually lost some of that sense of delight over the years reading primarily for school. So go out there and have fun with it.

My friend Tony Reinke recently came across an old editorial from J. I. Packer, written in 1985, talking about his leisure reading. Anyone who has met Packer probably knows that he used to devour mystery novels. But this may be the only place where he explains why—and in the process, encourages the act of light reading for fun.

The cat came out of the bag at a recent CT senior editors’ meeting. To avoid scandal, I give no names; but it emerged that for relaxation one of us reads westerns (Louis L’Amour), another goes for espionage thrillers (Frederick Forsyth), and I devour mysteries. (’Tecs I call them.) [Note from JT: I think ‘tec is short for detective.]

I started young, ingesting my first Agatha Christies when I was seven. Since then I have read, among others, all the Sherlock Holmeses, Father Browns, and Peter Wimseys; all the Ellery Queens, Agatha Christies, and Carter Dicksons; all the John Dickson Carrs and Dick Francises except one; all the full-length stories of Hammett, Chandler, James, and Crispin; and all the work of new arrivals Amanda Cross, Antonia Fraser, Simon Brett, and Robert Barnard; not to mention most of Margery Allingham, Austin Freeman, Freeman Wills Crofts, Erle Stanley Gardner, Rex Stout, Ruth Rendell, and Julian Symons.

What have I gained?

Fun, to start with. Where else could I have made the acquaintance of characters like Stout’s Nero Wolfe (world’s heaviest genius and largest ego), Dickson’s Sir Henry Merrivale (the Old Man, but no gentleman), Gardner’s Perry Mason (incompetent, irrelevant, and immaterial), Christie’s Miss Marple (mesmeric village knit-wit), and the prewar Poirot, who bounced and burbled like Maurice Chevalier?

I have also gained some elementary instruction, learning chemistry from Freeman’s Dr. Thorndyke, railway operation from Crofts’s Inspector French, basic Christianity from Chesterton’s Father Brown, Reformed Judaism from Kemelman’s Rabbi Small, post-Vatican II Catholicism from Kienzle’s Father Koesler, and up-to-date liberal Methodism from Merrill Smith’s Reverend Randollph.

But it is not for general education that I read ’tecs, nor for examples of life and instruction of manners, for which the Thirty-nine Articles say that Anglicans read the Apocrypha. What I enjoy is the poignant perplexity of the puzzle, the sleuth’s superior brainwork, and the doing of justice by clearing the innocent and exposing the guilty.

Ought my fellow senior editors and I repent of time wasted in our light reading? Not necessarily. If overloaded academic and literary people never read for relaxation, their brains will break. And ’tecs, thrillers, and westerns, while not great literature, are among the most moral fiction of our time. Goodies and baddies are distinguished and killers finally get it in the end. Writing that upholds fundamental morality is neither degenerate nor corrupting.

Also, these are stories of a kind that would never have existed without the Christian gospel. Culturally, they are Christian fairy tales, with savior heroes and plots that end in what Tolkien called a eucatastrophe—whereby things come right after seeming to go irrevocably wrong. Villains are foiled, people in jeopardy are freed, justice is done, and the ending is happy. The protagonists—detectives, Secret Service agents, noble cowboys and sheriffs, or whatever—are classic Robin Hood figures, champions of the needy, bringers of merited judgment and merciful salvation. The gospel of Christ is the archetype of all such stories. Paganism unleavened by Christianity, on the other hand, was and always will be pessimistic at heart.

Do I urge everyone to read detective and cowboy and spy stories? No. If they do not relax your mind when overheated, you have no reason to touch them. Light reading is not for killing time (that’s ungodly), but for refitting the mind to tackle life’s heavy tasks (that’s the Protestant work ethic, and it’s true).

You must find what refreshes you, as your senior editors have found what refreshes them. And if you will not accuse us of being wicked worldlings for our light reading, I will not accuse you for watching all those TV sitcoms and sports programs that so bore me. Fair? Surely—and Christian, too.

[J. I. Packer, “From the Senior Editors: ’Tecs, Thrillers, and Westerns,” Christianity Today (Carol Stream, IL: Christianity Today, 1985), 12.]

November 27, 2018

The First Christmas: God’s Mission to Earth

A new film from SpeakLife UK.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers