Justin Taylor's Blog, page 260

December 2, 2011

Jerram Barrs on Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

Jerram Barrs—Professor of Christian Studies and Contemporary Culture at Covenant Theological Seminary, and Resident Scholar of the Francis A. Schaeffer Institute—talks about his love for the book Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. (Warning: contains spoilers!)

Struggling to Learn Greek?

If you're a seminary student struggling to learn Greek, this testimony from a fellow struggler may encourage you:

In my first year of Greek at Biola University, I nearly failed the subject. The professor, Dr. Harry Sturz, had compassion on me and gave me a passing grade. I took a different professor in second-year Greek. He gave us a battery of exams at the beginning of the semester. One exam each week. I failed the first exam. I failed the second exam. I failed the third exam. I failed the fourth exam, but it was a high F! And I got a D on the fifth exam. "Hey," I thought, "I'm really getting this Greek thing down!"

The professor called me into his office and told me that I should check out of Greek. That was the wake-up call I needed. I went down to my dorm room, got on my knees, and confessed to the Lord that I had dragged his name through the mud. I reasoned that since I am in Christ and he is in me, he was failing Greek, too. And even though I was at a Christian school, I was soiling his reputation. I repented of my sin—the sin of mediocrity because I was surrounded by Christians, the sin of thinking that I did not need to do my best since I was a Christian.

I went back to the professor and asked for one more chance. He granted that to me. I ended up getting an A in the class both semesters. It still took me two more years of Greek at Biola before I even felt moderately comfortable with the language, but I had learned my lesson. Now, to be sure, my experience is not everyone's. But, for me, learning Greek became a matter of spiritual discipline. And even though I was very sick in my fourth semester of Greek-so that I missed five and a half weeks of school-I still did well in the course.

I don't consider myself good at languages, but I do consider myself a steward of the life that God has given to me. And I have never recovered from the impact that the Greek New Testament has made on my walk with Christ.

The author? Dan Wallace, who went on to write a standard intermediate textbook, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics.

(You can also read an interview I did with Professor Wallace back in 2008, where he recounts how a bizarre strain of viral encephalitis led to memory loss, with the result that he no longer knew Greek and had to reread his own grammar to learn it over again!)

The quote above is from Constantine Campbell's Keep Your Greek: Strategies for Busy People, which looks like a very practical and down-to-earth motivational guide to retaining Greek.

D.A. Carson's Theological Method

Below is an outline of Andy Naselli's essay, "D. A. Carson's Theological Method" (PDF), published in the Scottish Bulletin of Evangelical Theology 29 (2011): 245-74:

1. Carson's Background: Some Factors That Influence His Theological Method

1.1. Carson's Family

1.2. Carson's Education

1.3. Carson's Professional Experience

1.4. Some Other Background Factors

2. Carson's Corrigible Presuppositions

2.1. Carson's Metaphysics: God

2.2. Carson's Epistemology: Chastened Foundationalism

2.3. Carson's Bibliology

3. Carson's Understanding of the Tasks of the Theological Disciplines

3.1. Exegesis

3.2. Biblical Theology (BT)

3.3. Historical Theology (HT)

3.4. Systematic Theology (ST)

4. Carson's Understanding of the Interrelationships of the Theological Disciplines

4.1. Theological Hermeneutics

4.2. Exegesis and BT

4.3. Exegesis and HT

4.4. Exegesis and ST

4.5. HT and ST

4.6. BT and HT

4.7. BT and ST

4.8. Exegesis, BT, HT, ST, and Practical Theology (PT)

4.9. Spiritual Experience and the Theological Disciplines

5. Conclusion

What Is Unbelief?

St. Hilary of Poitiers (c. AD 315-67):

"All unbelief is foolishness, for

it takes such wisdom as its own finite perception can attain,

and measuring infinity by that petty scale,

concludes that what it cannot understand must be impossible.

Unbelief is the result of incapacity engaged in argument."

—De Trinitate, III.24, cited in Douglas Kelly, Systematic Theology, vol. 1, p. 19.

December 1, 2011

An Interview on "The Theology of Jonathan Edwards"

Michael McClymond (associate professor of theological studies at Saint Louis University) and Gerald McDermott (Jordan-Trexler professor of religion at Roanoke College) were kind enough to answer some questions about their new book, The Theology of Jonathan Edwards (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Michael McClymond (associate professor of theological studies at Saint Louis University) and Gerald McDermott (Jordan-Trexler professor of religion at Roanoke College) were kind enough to answer some questions about their new book, The Theology of Jonathan Edwards (Oxford University Press, 2011).

How did each of you come to be interested in Edwards and his theology?

Gerry: I had intended to write my dissertation on the civil religion of JE and the New Divinity back in the mid-80s, and then realized the public theology of JE was plenty big for a book. Besides, I soon realized that Edwards had a far greater mind than his disciples' and was worthy of a lifetime of study.

Michael: My interest in Edwards started while I was studying at Yale Divinity School. David Kelsey did a seminar on "The Reformed Tradition," giving special attention to John Calvin, Jonathan Edwards, and Karl Barth. You might say that I got stuck in the middle. The in-between guy seemed to have gotten a lot of attention from American historians and literary analysts, but less from theological readers. Then in 1985 I received a Christmas gift of the two-volume, Banner of Truth edition of The Works of Jonathan Edwards. Christian Book Distributors offered it, as I recall, for only $35. Given the number of pages, and the size of the font, these two volumes had more theological bang for the buck than any other book I ever got. I read End of Creation and was hooked by this conceptually sophisticated and yet spiritually edifying account of God. I was drawn in by that great vision of God's glory that also drew Edwards in. My University of Chicago dissertation centered on End of Creation. Later I was pleased to see John Piper republish this work, and assign it great importance.

How did the two of you team up to write this book together?

Gerry: Mike approached me several years ago with the idea, and came up with an initial Table of Contents which we then revised. It just so happened that I was due for a sabbatical. As it turned out, I spent a whole year doing nothing else but work on this book, and Mike spent nearly the same amount of time.

Michael: The timing of Gerry's academic leave and mine—in retrospect—seems providential. With the completion of The Works of Jonathan Edwards, it struck me that it was high time for someone to do a fresh examination of the whole of Edwards's theology. Yet it struck me that this might be a very lonely task for any one person. So I feel extremely fortunate to have been able to collaborate with Gerry on this. Our earlier publications on Edwards seemed to juxtapose—like the alphabetization of our names. If placed into a directory, "McClymond" and "McDermott" would land very near one another.

How long did it take to write such a sizable volume, and how did you go about it?

Gerry: It was a gargantuan task, larger than either of us imagined. As we said, it took a full year for both of us, doing little besides. We divided the chapters between us, edited all of them together, and sent them out to many JE experts for feedback.

Michael: I give Gerry credit for keeping the project moving at some points where I was getting bogged down with one or another chapter. I admit to having perfectionistic tendencies, and that can be a fatal thing when one is dealing with 73 volumes of primary text, as well as some 5000 secondary books, articles, and dissertations. He who hesitates is lost. When it comes to Edwards, one could always spend more time in reading and reflection. In the preface to our book we say that "we hope the book will serve as a starting point for many new lines of inquiry and investigation." There is so much more to say about Edwards. Perhaps our book will help to encourage a rising generation of scholars on Edwards—not to mention the preachers and Christian leaders and activists we also hope to inspire with this book.

Has anything like this—a comprehensive theology of Edwards—been attempted before?

Gerry: Not on this scale. This is the largest single-volume treatment of JE's theology ever attempted. John Gerstner did a 3-volume overview of Edwards's theology, but much of it was primary source material, and his perspective was more rationalistic and less comprehensive than ours. Another difference is that ours is based on what was not available to Gerstner or anyone else before now—the full 73-volume corpus prepared by the Yale edition. Furthermore, we have reviewed all the secondary literature produced in the last twenty years that has appeared since Gerstner's death.

Michael: The Princeton Companion to Edwards included nineteen chapters on Edwards's thought, and yet ours includes forty-five chapters. What is more, an edited volume—like the Princeton Companion—is not able, so to speak, to connect the dots in Edwards's thinking. Attentive readers will find that our book contains literally hundreds of internal cross-references—"(see ch. 13)," "(ch. 4, 8, 19)," etc. These are points in our exposition of Edwards where it would be tedious to repeat the argument presented in another context. Our book on Edwards is in fact a single argument, stretching from chapter 1 to chapter 45.

Assuming it's possible to speak of the "center" of Edwards's theology, how would you summarize it?

Gerry: We think it is misleading to speak of one center. Therefore our book speaks of multiple aspects—Trinitarian communication, creaturely participation, necessitarian dispositionalism, theocentric voluntarism, and harmonious constitutionalism. Like Augustine, Luther, and Calvin, it is dangerous to speak of one center, for such description necessarily misses much of the density and diversity of a great thinker's vision. On the other hand, we do suggest throughout the volume that Edwards's aestheticism—and its centrality to his vision of God—is singular in the history of Christian thought.

Michael: I echo Gerry's point. The history of scholarship on Edwards has shown the danger of locating any one central idea, theme, or motif—as though Edwards's thought was like a bicycle wheel in which every spoke linked to a single center. The opening pages of our book, using the symphony analogy, suggests that the different parts of the orchestra—strings, woodwinds, horns, etc.—are all playing at the same time. The major themes move back and forth from the acoustical foreground to the background, and then reverse themselves once again as the music continues. Does every thinker have to have a single "center"? Not necessarily. If one examines the literature on the Apostle Paul, one finds competing ideas as to what is the true "center" of Paul's thought. Was it eschatology? Justification? Union with Christ? Freedom in Christ? The uniting of Jew and Gentile? Scholars have made a reasonable case for each of these. In a complex thinker like Paul, it isn't necessary to focus on a single center. So it is for Edwards too.

Calvin doctrinal rule of "modesty and sobriety" was that we should not "speak, or guess, or even to seek to know, concerning obscure matters anything except what has been imparted to us by God's Word" (Inst. 1.14.4). What advantages and drawbacks might there be to Edwards's more speculative and imaginative approach in certain areas?

Gerry: The greatest advantage of course is that Edwards is more theological than many, if by theology we mean reflection on the meaning and implication of divine revelation. The consequent disadvantage is the danger of going beyond biblical testimony in ways that confuse Christ and culture, or bind the church too closely to one philosophy or temporal framework. But all theology necessarily goes beyond repeating the mere words of Scripture, and should! So the real question is not whether we should discuss what is obscure, for all theology must do so in order to be theology, but whether it does so in disciplined ways. For the most part, I think, Edwards shows biblical and traditional discipline without letting the latter prevent him from seeing things in new and helpful ways.

Michael: This is a challenging question! I am tempted to answer with the immortal slogan of the National Enquirer newspaper: "Enquiring minds want to know." Of course, for tabloid readers this slogan means a need to know the gossip about the latest Hollywood scandals, mishaps, and divorces. Yet Edwards's burning curiosity turned toward the being of God, the will of God, the ways of God, the works of God, and the final purposes of God. John Piper refers to Edwards as "God-besotted." It is hard to fault him for having this particular passion—even if at time his thinking verges toward the outer limits of what human beings can possibly know about God. Regarding Calvin, I am not completely convinced that Calvin himself consistently followed his own rule of "modesty and sobriety." When challenged on the topic of predestination, it seems to me that Calvin may have expatiated further and said more than he should have said. This is not, however, to minimize or detract from Calvin's vast contributions to biblical interpretation, theology, and Christian practice.

For those who know Edwards, there's widespread agreement that the common picture of Edwards as only the morbid, graceless preacher of "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" is a caricature. But I wonder if there are other pictures of Edwards—in the evangelical Calvinist world, or in the scholarly community—that you might want to correct, even if the distortions aren't nearly as grotesque as the pop culture version.

Gerry: We think we correct a number of scholarly distortions and misrepresentations, such as the notions that 1) Edwards never changed in his basic outlooks or theological approaches, 2) his idea of sola scriptura dismissed the use of tradition in both principle and practice, 3) his use of "affections" meant that true religion is rooted in emotion, 4) Edwards departed from Calvinist covenantalism, 5) Edwards perpetuated traditional Calvinist uses of the covenant, 6) his doctrine of justification is what has been considered traditionally Protestant, 7) his theology can rightly be deployed against the basic structures of Catholic and Eastern Orthodox theology, 8) his eschatology was provincial and Americanist, predicting the imminent outbreak of the millennium in New England, 9) Edwards had little or no sacramental theology, 10) he had little or no concern for those outside the church, 11) he was uninterested in world religions, and 12) the principal distinctiveness of his theology is that it is for America and by a proto-American.

Michael: Gerry has already summarized the principal points. I would also call attention to the element of desire and delight. Edwards was not so much compelled by moral obligation as drawn by divine beauty. I recall an incident many years ago, when I was walking around the old city of Jerusalem, and I accidentally stumbled across the Russian Cathedral in Jerusalem. The church door, just cracked open, revealed the most beautiful frescoes depicting Christ and the saints. I simply had to go in. Edwards's life was like that. Very early on, he had a glimpse of something so beautiful that he chose to spend the rest of his life exploring it. This picture of an enraptured Edwards is poles apart from the popular misconception of a narrow, parsimonious, judgmental person.

I know that this is an academic tome, and that there must be an element of academic detachment associated with a project like this, but I wonder if you could relay to readers the personal effect that living with Edwards' theology has had upon you?

Gerry: I have become more overwhelmed than ever by the massive mind and sensitive spirit of Jonathan Edwards. His work has challenged me to think ever more with him before I settle on my own theological conceptions, and to try to imitate his hungry heart for God. Furthermore, his determination to sacrifice anything and everything in his pursuit of deeper intimacy with the Triune God continues to challenge me.

Michael: Edwards's complete consecration of his life and thought to the glory of God is a great challenge to me—as I know it has been to so many others. Only a holy person can write books that stir others to holiness. What is more, the completion of the book feels to me like a graduation ceremony. Now I am ready to launch into whatever new thing God might have in store. And with Edwards, I want to say: "Resolved, to live with all my might, while I do live."

In your view, what is the greatest lesson that Edwards's theology has for today's church and academy?

Gerry: We believe (and argue in our book) that Edwards's theology is perfectly suited for global Christianity in the 21st century. For it is a bridge (as we try to show) between Protestants and Catholics, East and west, charismatics and non-charismatics, and liberals and conservatives. It exalts not only the Word in ways that evangelicals hold dear, but also the Spirit in ways that Pentecostals appreciate, and the Trinity in ways that resonate with both Catholics and Orthodox.

Michael: When reading Edwards, I sometimes think: "What a brilliant mind!" But more often than not, something else comes to mind: "What an awesome God!" To me, this is the highest testimonial that one could give to Edwards, and the one that he would most appreciate. Edwards ultimately does not call attention to himself but to the God he served so diligently and indefatigably.

The Complementarian Publishing Conundrum

An insightful comment from Tom Schreiner:

Sometimes I wonder if egalitarians hope to triumph in the debate on the role of women by publishing book after book on the subject. Each work propounds a new thesis which explains why the traditional interpretation is flawed. Complementarians could easily give in from sheer exhaustion, thinking that so many books written by such a diversity of different authors could scarcely be wrong. Further, it is difficult to keep writing books promoting the complementarian view. Our view of the biblical text has not changed dramatically in the last twenty five years. Should we continue to write books that essentially promote traditional interpretations? Is the goal of publishing to write what is true or what is new? One of the dangers of evangelical publishing is the desire to say something novel. Our evangelical publishing houses could end up like those in Athens so long ago: "Now all the Athenians and the strangers visiting there used to spend their time in nothing other than telling or hearing something new" (Acts 17:21, NASB).

Discerning the Good and Bad in Technology

From an interview with media ecologist Read Schuchardt:

What's bad and good about technology?

It's fast, cheap, effective, and cool. That's the good part.

The bad part is that it's fast, cheap, effective, and cool.

If we become what we behold, my concern with technology is not what we do with it, but what it does to us.

The analogy I've been using most recently is the question of prostitution. What's wrong with prostitution is fairly obvious, but in general it's always going to be there, from being the world's oldest profession to being increasingly legalized all around the globe. The answer to the "problem" of prostitution is, I believe, not actually to be engaged on the mass or group level, but on the individual level. This is why neither Jesus nor Thomas Aquinas (for example) argue against prostitution, but do argue against the personal effects. The Ten Commandments obliges the individual to "not commit adultery"—it never suggests that thou shalt outlaw prostitution. Jesus forgives the woman caught in adultery, on the one hand, but on the other he doesn't makes light of her sin and he gives a far sterner warning to men: if you have lusted after a woman internally then this is tantamount to adultery. So he both raises the personal bar and lowers the group cost.

And this gets to the heart, I think, of both real freedom and how real freedom in the face of technological determinants should be conceived—we don't want sobriety by outlawing alcohol, we want sobriety by achieving self-control while in a bar with friends. Which is to say, freedom comes on the individual level, which is always highly contextualized, contingent, and culturally framed.

People in Singapore aren't free from the negative effects of chewing gum; they are free from the temptation of chewing gum because the whole country has outlawed it. That's not real freedom, which always involves a choice. In the same way, there is no technology, even those that are inherently "bad," that should be eliminated (okay: maybe nuclear weapons could go), but there are collective effects of technology that individuals can be made aware of and can personally resist.

So I can walk while texting and call it multitasking, but if it makes me bump into things or people I can also be conscious of this likely effect and thereby choose to text only when I'm not moving so I don't pose a risk to myself or others.

What technologies are good and helpful?

This is an unanswerable question, because it forces a non-existent dichotomy. All technologies have a "good and helpful" aspect and they also have a harmful and debilitating effect. I like chairs, which seem utterly neutral or positive as a technological invention—especially nice big, comfy chairs. But cultures that sit on chairs experience more colon cancer than cultures that squat. Neil Postman argued that all technologies are a "Faustian bargain"—they give something, and they take something away. Freedom, I think, comes in knowing what these two things are, and in making the choice of which you value more. In our household, we're still not squatting.

One of my favorite technologies is the bicycle, since I can hardly think of anything bad that could come from it, and since it increases, health, happiness, and enjoyment of the outdoors in almost all its uses. But if you're Lance Armstrong, chances are good you know precisely what can go wrong if you ride a bike too much.

How does one discern between good and bad technology? Discernment is the key, and it is discernment not that tells you which is good and which is bad, but tells you that every technology has both a good and a bad side, and then lets you discern whether or not you want to use it.

My favorite example of this is the Bruderhof community who noticed that after using television for a year, their children had stopped singing the community songs and spiritual hymns they used to sing on the playground. So the decision was not over the question, "Is television good or bad?" The question became, "Which do we value more: good television or singing children?" And that to me is true discernment.

(HT: First Things)

Darwin on Trial: 20 Years Later

In the latest issue of Touchstone Phillip E. Johnson reflects on the state of the conversation twenty years after the publication of his landmark book Darwin on Trial.

In the latest issue of Touchstone Phillip E. Johnson reflects on the state of the conversation twenty years after the publication of his landmark book Darwin on Trial.

Here is his hopeful conclusion:

"I am confident that when we finally get a fair hearing before a scientific community that concurs with the principle that important terms must be defined clearly and used consistently, then the better logic will prevail and Darwinism will be relegated to intellectual history. My effort is not aimed at getting a popular majority to overrule the scientific community, but at appealing to the community of scientists to strive for freedom from those prejudices that interfere with clear-headed, logical thinking. In this era of springtime liberations, surely intellectual freedom will be restored in science."

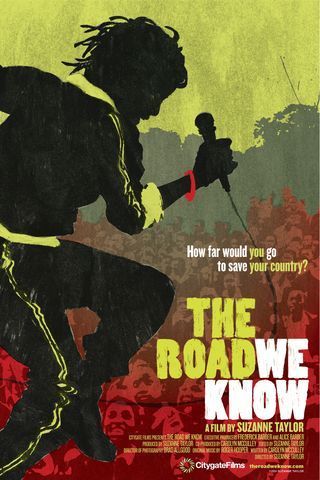

Filmanthropy: Watch a Movie, Save a Life!

So, my friends, it's World AIDS Day, which actually kicks off AIDS Awareness Month. I know this isn't usually the topic people want to consider during the holidays, but I'm actually kind of excited myself. The reason is because for the past year, I've been immersed in the topic of HIV prevention and the AIDS pandemic in Africa, thanks to Citygate Films' newest film, THE ROAD WE KNOW. More importantly, there's actually some good news on the horizon about reducing HIV infections!

And that's the message of THE ROAD WE KNOW. This film follows seven college students in Botswana who are boldly challenging conventional wisdom about AIDS in Africa to bring the low-cost, dignified message of sexual restaint to their younger peers. They were filmed in 2009 by my colleague, Suzanne Taylor, who directed and edited this production. Suzanne found out about them through the global missions fund of Johnson Ferry Baptist Church in Marietta, GA. These Botswana college students are all Christians who are motivated by their faith to intervene in a crisis where one in four adults (ages 15 to 49) are infected with HIV. Can you imagine living among such an epidemic? It's almost unthinkable.

Yet as we were finishing the post-production on this project, we read a special report from the UNAIDS organization that talked about how young adults are leading the revolution in HIV prevention. In this 2010 report, UNAIDS could point to a 25 percent drop or more in new infections for young adults ages 15 to 24 in 15 of the most infected nations–primarily due to sexual behavior change! This confirmed that what we had documented in Botswana was not an isolated trend.

Today we are releasing this film. It won't be in theaters near you. It will, in fact, be even closer than that. Citygate Films has the privilege of participating in the beta project of an exciting innovation in online video viewing. We have teamed up with European technology company UbicMedia™ and its proprietary PUMit tool to allow audiences to digitally share our film, while simultaneously contributing to a fund to further develop youth HIV/AIDS prevention programs in Botswana. UbicMedia actually approached our film promotion team, CrowdStarter, to find an independent film to pioneer this technology and we were very pleased to be selected to be part of this beta project.

"Ubicmedia is working with leading U.S.-based entertainment networks and file-sharing and content management companies," says UbicMedia's Olivier Pfeiffer. "The global importance of the theme addressed by Suzanne Taylor in THE ROAD WE KNOW is a perfect fit to showcase the flexibility and the virality of our solution. We're all very happy to potentially increase the awareness around the cause and the amount of collected funds through the use of UbicMedia's technology."

So I'm asking you to check out our "Watch the Film, Save a Life" campaign–and then spread the good news about both the film and the youth revolution in HIV prevention!

You can read more about it here.

Tim Keller Talks to Google on the Meaning of Marriage

On November 14, 2011, Tim Keller visited Google to talk about his book The Meaning of Marriage:

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers