Justin Taylor's Blog, page 226

March 22, 2012

Flee Youthful Passions—Like Arguing Too Much

Phillip Jensen on some of the mistakes he's made:

Phillip Jensen on some of the mistakes he's made:

The first is that as a young man I enjoyed a fight too much. I grew up in a family of brothers. We fought a lot, and I grew up through debating and arguing, and I liked a good argument. A very kind senior academic came and talked to me years ago, and pointed out that when the Bible urges us to "flee the passions of youth", it's not talking about sex. It's talking about argumentativeness, if you look at the context (in 2 Tim 2). The Lord's servant must not be argumentative, but teach patiently and pray that God may change your heart. So as a young man, my own personality and argumentativeness was too strong. So that was a lesson to learn.

And a balancing word from his advice to those starting in ministry:

You've got to take up your cross and follow Jesus. So this is no career move for the faint-hearted. This is no career move for someone who wants an easy life or a nice life. You're not going to be accepted, and you're not going to be liked: you are following the crucified one.

So grasp that reality before you start. That's not an invitation for nasty people to join the ministry. If you enjoy conflict you have a spiritual problem. But if you withdraw from conflict, or think you're going to win people over by niceness, you have a major problem because you're not actually dealing with Christianity. People like using the suffering servant of the cross as an image of loving service. It is that. But it is also an image of painful martyrdom and alienation and rejection. That's what Christian ministry is always going to be about.

You can read the whole thing here.

Sin Is Satanic

Sin is not a thing we can just sweep under the rug. It's not a little this or that. Oh no. Sin is most fundamentally our acting like Satan instead of reflecting the glory of God. . . .

Fudging on the truth, spinning things a bit, ignoring God's word, elevating our reason above what he's said — these are neither struggles nor foibles, they are Satanic. It is to deny the most fundamental purpose we exist: to glorify God and bear the imprint of his holiness.

Read the whole thing, which includes G.K. Beale's exposition of how Adam, in his fall, began to resemble the Serpent.

March 21, 2012

An Interview with Daniel B. Wallace on the New Testament Manuscripts

As Craig Blomberg has written, "Dan Wallace has clearly become evangelical Christianity's premier active textual critic today." In addition to teaching New Testament at Dallas Theological Seminary, he serves as executive director of the cutting-edge Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (CSNTM). He recently made quite a stir when he announced that next year an academic publication will reveal the discovery of a first-century fragment from the Gospel of Mark. (See, for example, this interview with Hugh Hewitt.)

As Craig Blomberg has written, "Dan Wallace has clearly become evangelical Christianity's premier active textual critic today." In addition to teaching New Testament at Dallas Theological Seminary, he serves as executive director of the cutting-edge Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (CSNTM). He recently made quite a stir when he announced that next year an academic publication will reveal the discovery of a first-century fragment from the Gospel of Mark. (See, for example, this interview with Hugh Hewitt.)

He was kind enough to answer some questions about the discipline of textual criticism, the number of manuscripts, the earliest manuscripts (including the soon-to-be famous fragment), why the process of copying is nothing like the "telephone game," and other questions.

What is "textual criticism?"

Textual criticism is the discipline that attempts to determine the original wording of any documents whose original no longer exists. There are other, secondary goals of textual criticism as well, but this is how it has been classically defined.

This discipline is needed for the New Testament, too, because the originals no longer exist and because there are several differences per chapter even between the two closest early manuscripts. All New Testament manuscripts differ from each other to some degree since all are handwritten manuscripts.

How many NT manuscripts do we know of?

As far as Greek manuscripts, over 5800 have been catalogued. The New Testament was translated early on into several other languages as well, such as Latin, Coptic, Syriac, Armenian, Georgian, Gothic, etc. The total number of these versional witnesses has not been counted yet, but it certainly numbers in the tens of thousands.

At the same time, it should be pointed out that most of our manuscripts come from the second millennium AD, and most of our manuscripts do not include the whole New Testament. A fragment of just a verse or two still counts as a manuscript. And yet, the average size for a NT manuscript is more than 450 pages.

At the other end of the data pool are the quotations of the NT by church fathers. To date, more than one million quotations of the NT by the church fathers have been tabulated. These fathers come from as early as the late first century all the way to the middle ages.

What's the earliest manuscript we have?

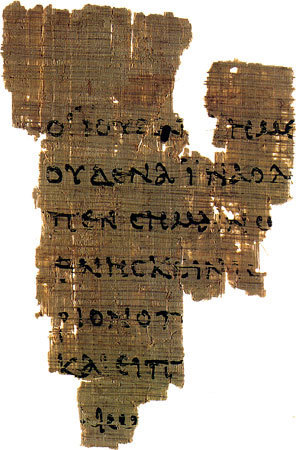

Up through the end of 2011, the following would be the answer: A papyrus fragment that had been sitting in unprocessed ancient documents at the John Rylands Library of Manchester University, England, is most likely the earliest NT document known today. Known as P52 or Papyrus 52, this scrap of papyrus has John 18:31-33 on one side and John 18:37-38 on the other.

Up through the end of 2011, the following would be the answer: A papyrus fragment that had been sitting in unprocessed ancient documents at the John Rylands Library of Manchester University, England, is most likely the earliest NT document known today. Known as P52 or Papyrus 52, this scrap of papyrus has John 18:31-33 on one side and John 18:37-38 on the other.

It was discovered in 1934 by C. H. Roberts. He sent photographs of it to the three leading papyrologists in Europe and got their assessment of the date—each said that it was no later than AD 150 and as early as AD 100. A fourth papyrologist thought it could be from the 90s. Since the discovery of this manuscript, as many as eleven NT papyri from the second century have been discovered.

On February 1, 2012, I made the announcement in a debate with Dr. Bart Ehrman at UNC Chapel Hill, that as many as six more second-century papyri had recently been discovered. All of them are fragmentary, having only one leaf or part of a leaf. One of them rivals the date of P52, a fragment from Luke's Gospel. But the most significant find was a fragment from Mark's Gospel, which a leading paleographer has dated to the first century!

What makes this so astounding is that no manuscripts of Mark even from the second century has surfaced. But here we may have a document written while some of the first-generation Christians were still alive and before the NT was even completed. All seven of these manuscripts will be published by E. J. Brill sometime in 2013 in a multi-author book. Until then, we should all be patient and have a "wait and see" attitude. When the book comes out it will be fully vetted by textual scholars.

How does the number of NT manuscripts compare to other extant historical documents?

NT scholars face an embarrassment of riches compared to the data the classical Greek and Latin scholars have to contend with. The average classical author's literary remains number no more than twenty copies. We have more than 1,000 times the manuscript data for the NT than we do for the average Greco-Roman author. Not only this, but the extant manuscripts of the average classical author are no earlier than 500 years after the time he wrote. For the NT, we are waiting mere decades for surviving copies. The very best classical author in terms of extant copies is Homer: manuscripts of Homer number less than 2,400, compared to the NT manuscripts that are approximately ten times that amount.

What are the different kinds of variants, and how do they affect the meaning of the texts?

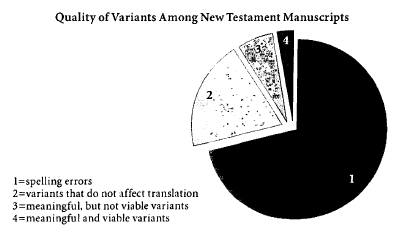

The variants can be categorized into four kinds:

Spelling and nonsense readings

Changes that can't be translated; synonyms

Meaningful variants that are not viable

Meaningful and viable variants

Let me briefly explain each of these.

Spelling and nonsense readings are the vast majority, accounting for at least 75% of all variants. The most common variant is what's called a movable nu—that's an 'n' at the end of one word before another word that starts with a vowel. We see the same principle in English with the indefinite article: 'a book,' 'an apple.' These spelling differences are easy for scholars to detect. They really affect nothing.

The second largest group, changes that can't be translated and synonyms, also do not affect the meaning of the text. Frequently, the word order in the Greek text is changed from manuscript to manuscript. Yet the word order in Greek is very flexible. For the most part, the only difference is one of emphasis, not meaning.

The third group is meaningful variants that are not viable. By 'viable' I mean a variant that can make a good case for reflecting the wording of the original text. This, the third largest group, even though it involves meaningful variants, has no credibility. For example, in Luke 6:22, the ESV reads, "Blessed are you when people hate you and when they exclude you and revile you and spurn your name as evil, on account of the Son of Man!" But one manuscript from the 10th/11th century (codex 2882) lacks the words "on account of the Son of Man." That's a very meaningful variant since it seems to say that a person is blessed when he is persecuted, regardless of his allegiance to Christ. Yet it is only in one manuscript, and a relatively late one at that. It has no chance of reflecting the wording of the original text, since all the other manuscripts are against it, including quite a few that are much, much earlier.

The smallest category by far is the last category: meaningful and viable variants. These comprise less than 1% of all textual variants. Yet, even here, no cardinal belief is at stake. These variants do affect what a particular passage teaches, and thus what the Bible says in that place, but they do not jeopardize essential beliefs.

Isn't the process of copying a copy of a copy somewhat akin to the old "telephone game"?

Hardly. In the telephone game the goal is to garble an original utterance so that by the end of the line it doesn't resemble the original at all. There's only one line of transmission, it is oral rather than written, and the oral critic (the person who is trying to figure out what the original utterance was) only has the last person in line to interrogate.

When it comes to the text of the NT, there are multiple lines of transmission, and the original documents were almost surely copied several times (which would best explain why they wore out by the end of the second century).

Further, the textual critic doesn't rely on just the last person in the transmissional line, but can interrogate many scribes over the centuries, way back to the second century.

And even when the early manuscript testimony is sparse, we have the early church fathers' testimony as to what the original text said.

Finally, the process is not intended to be a parlor game but is intended to duplicate the original text faithfully—and this process doesn't rely on people hearing a whole utterance whispered only once, but seeing the text and copying it.

The telephone game is a far cry from the process of copying manuscripts of the NT.

One of Ehrman's theses is that orthodox scribes tampered with the text in hundreds of places, resulting in alterations of the essential affirmations of the NT. How do you respond?

Ehrman is quite right that orthodox scribes altered the text in hundreds of places. In fact, it's probably in the thousands. Chief among them are changes to the Gospels to harmonize them in wording with each other.

But to suggest that these alterations change essential affirmations of the NT is going far beyond the evidence. The variants that he produces do not do what he seems to claim. Ever since the 1700s, with Johann Albrecht Bengel who studied the meaningful and viable textual variants, scholars have embraced what is called 'the orthodoxy of the variants.' For more than two centuries, most biblical scholars have declared that no essential affirmation has been affected by the variants. Even Ehrman has conceded this point in the three debates I have had with him. (For those interested, they can order the DVD of our second debate, held at the campus of Southern Methodist University. It's available here.)

For those who want to explore further, could you give us a reading list of some of the chapters/papers you have written on textual criticism, from the most basic on up?

First, I would recommend my chapter, "The Reliability of the New Testament Manuscripts," in Understanding Scripture: An Overview of the Bible's Origin, Reliability, and Meaning (published by Crossway). It's a brief introduction, very user-friendly, to the issues involved. The rest of the book has excellent chapters on various aspects of biblical interpretation, reliability, and canon.

Next, I would recommend Reinventing Jesus, a book I co-authored with Ed Komoszewski and Jim Sawyer. This book wrestles with a number of issues—such as the historical reliability of the Gospels, the reliability of the manuscripts as witnesses to the original text, whether the ancient Church got the canon right (the 27 NT books), and whether they were right about the divinity of Christ. It's a solid primer on many of the hot topics about the New Testament today.

Finally, a book that came out last October called Revisiting the Corruption of the New Testament, which I edited and contributed to, takes head-on Bart Ehrman's Orthodox Corruption of Scripture. My essay is essentially the transcript of my debate with him at the Fourth Annual Greer-Heard Forum, held at New Orleans Baptist Seminary in April 2008. (For a more truncated version of my lecture, along with Ehrman's lecture, see The Reliability of the New Testament: Bart D. Ehrman and Daniel B. Wallace in Dialogue.) The rest of the chapters were written by my students and deal with various aspects of Ehrman's hypothesis.

New Ethnics in Christ

An encouraging and challenging talk from Leonce Crump II , lead pastor of Renovation Church in downtown Atlanta, on Colossians 3:11.

Is the Eternal Generation of the Son Really a Biblical Idea?

The early church held to the eternal generation of the Son of God, which can be defined as "the unique property [characteristic, attribute] of the Son in relation to the Father. Since God is eternal, the relation between the Father and the Son is eternal" (Robert Letham, The Holy Trinity, 499). Augustine provided a helpful analogy: it's not like "water flowing out from a hole in the ground or in the rock, but like light flowing from light" (De trin. IV.27, 172).

The early church held to the eternal generation of the Son of God, which can be defined as "the unique property [characteristic, attribute] of the Son in relation to the Father. Since God is eternal, the relation between the Father and the Son is eternal" (Robert Letham, The Holy Trinity, 499). Augustine provided a helpful analogy: it's not like "water flowing out from a hole in the ground or in the rock, but like light flowing from light" (De trin. IV.27, 172).

Keith Johnson summarizes the teaching in a bit more technical detail: "the Father eternally, necessarily, and incomprehensibly communicates the divine essence to the Son without division or change so that the Son shares an equality of nature with the Father yet is also distinct from the Father" ("Augustine, Eternal Generation, and Evangelical Trinitarianism," TrinJ 32 [2011]: 141-163).

This understanding is reflected in the original wording of the Nicene Creed (325 AD):

[We believe] in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten of the Father, the only-begotten; that is, of the essence of the Father, God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father.

If you want a very careful summary and introduction to Augustine's De trinitate (On the Trinity), see Johnson's Rethinking the Trinity and Religious Pluralism: An Augustinian Assessment (IVP, 2011). For those, like me, who aren't actively interesting in the issue of pluralism as it relates to the Trinity, I would recommend simply reading his summary exposition of Augustine's work.

The doctrine has fallen on hard times, however, and some of the evangelical theologians I admire the most don't think that the idea is biblical.

A full exegetical defense is obviously beyond the scope of a blog post, but I thought it might be helpful to excerpt a couple of sections from those who do think the idea is biblically defensible and theologically indispensable. These selections provide some helpful angles on this ancient doctrine.

First, in his new systematic theology—written with no footnotes except for biblical references!—Gerald Bray writes in God Is Love: A Biblical and Systematic Theology (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2012):

The framework within which we must understand the true meaning of "generation" with respect to the second person of the Trinity is established by the discipline of law, not by biology or grammar. As a legal principle, "generation" is fully consistent with the covenant principle and the structure of Old Testament revelation that provides the basic framework for understanding God's saving work. The relationship of the first to the second person of the Trinity is based on the concept of inheritance. The Son has been appointed the heir of all things, and it is in this sense that he is described as the firstborn of all creation [Col. 1:15-16; Heb. 1:2; see also Gal. 4:7]. By the law of primogeniture, the firstborn is the one who receives the inheritance, as the story of Esau and Jacob reminds us [Gen. 27:18-35; Jacob (the younger son) stole his brother's inheritance by impersonating him in the presence of his blind father Isaac].

In human affairs the language of inheritance is normally attached to the process of birth and human reproduction, but not always—it is quite possible to leave a legacy to someone totally unrelated to the donor, or to adopt others with the intention of giving them an inheritance, as God has done with us [Gal. 3:29; Eph. 3:6]. The concept is flexible and can be applied to different situations by choice, not merely by necessity, which makes it so valuable for understanding both our relationship to God and the relationship of the Son to the Father.

The use of Father-Son language serves the additional purpose of emphasizing the underlying unity of being that binds them together and makes it possible for us to say that the Son is the Father's natural heir, whereas we are heirs only by the grace of adoption. "Like father, like son" is a well-known popular expression that conveys the essence of this and reminds us that, just as a human child shares the nature of his parents, so the Son of God must share the nature of his Father if he is to be a genuine Son. The shared being and nature are inherent in the terminology used to describe them. It is true that angels, and perhaps other heavenly beings, are occasionally called "sons of God" in the Old Testament, but this refers to their spiritual nature, which is like that of God himself, and is not connected to any inheritance that might be reserved for them [Gen. 6:2-4; Job 1:6; 2:1]. In that sense, the Son is the only begotten, as the prologue to John's Gospel specifies and as the creeds of the early church repeat [John 1:14].

D. A. Carson, writing in his Gospel according to John Pillar commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990), looks at a very interesting verse: "For as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself" (John 5:26). Carson writes:

The logical For (gar) is important: this verse explains how it is that the Son can exercise divine judgment and generate resurrection life by his powerful word. It is because, like God, he has life-in-himself. God is self-existent; he is always 'the living God'. Mere human beings are derived creatures; our life comes from God, and he can remove it as easily as he gave it. But to the Son, and to the Son alone, God has imparted life-in-himself.

This cannot mean that the Son gained this prerogative only after the incarnation. The Prologue has already asserted of the pre-incarnate Word, 'In him was life' (1:4). The impartation of life-in-himself to the Son must be an act belonging to eternity, of a piece with the eternal Father/Son relationship, which is itself of a piece with the relationship between the Word and God, a relationship that existed 'in the beginning' (1:1). That is why the Son himself can be proclaimed as 'the eternal life, which was with the Father and has appeared to us' (1 Jn. 1:2).

Many systematicians have tied this teaching to what they call 'the eternal generation of the Son'. This is unobjectionable, though 'the eternal generation of the Son' should probably not be connected with the term monogenēs (sometimes translated 'only begotten': cf. notes on 1:18). In the immediate context, it is this eternal impartation of life-in-himself to the Son that grounds his authority and power to call the dead to life by his powerful word.

Arriving Early for T4G?

If you're going to T4G and arriving on Monday, there's an event that evening that may be of interest: Russell Moore will host a panel on Christ-centered theology and ministry with Josh Harris, Carl Trueman, Matt Pinson, and J.D. Greear. Dinner will be from Chuy's Tex Mex.

It's from 6:00-8:00 p.m., with dinner served in Heritage Hall and the dialogue held in Alumni Chapel. The cost is $15 and you have to register by April 5.

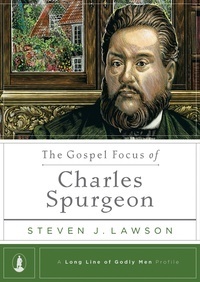

The Gospel Focus of Charles Spurgeon

Given the influence of Charles Spurgeon's preaching and gospelcentric theology, I'm surprised there aren't more books on him.

Given the influence of Charles Spurgeon's preaching and gospelcentric theology, I'm surprised there aren't more books on him.

Reformation Trust has now published a new introduction that looks very helpful: Steve Lawson's The Gospel Focus of Charles Spurgeon. Spurgeonophile Phil Johnson writes:

I own at least three dozen different biographies of the prince of preachers, but Steve Lawson's new book on Charles Spurgeon will from now on have a key place of prominence in my short list of favorites. Dr. Lawson understands what made the great preacher's heart beat: it was the gospel, charged with a passion for the souls of lost people and kept steady by the doctrines of grace.

You can preview it below:

Open publication – Free publishing – More evangelism

Economics for Everybody

Ligonier Ministries and Compass Cinema are partnering together to produce a new video curriculum on economics from a biblical perspective, called Economics for Everybody. they write, "We want it to be fun, interesting, and perhaps even a bit controversial."

You can follow Thomas Purifoy's blog on the project here, and watch the first lesson below:

A Kony 2012 Response

This video cost $0 to make. There is no kit for sale. No bracelet to wear. No poster to put up. There is no one to make famous.

Charles is a former abducted child soldier who through the grace of God has chosen to forgive his captors rather than seek revenge. We believe that the weapon that will change the issue of Kony and the many children affected by his atrocities is the releasing power of forgiveness.

You may wonder if we believe Kony should be brought to justice. Absolutely! We praise God that Invisible Children has helped bring these atrocities into the light once again, and we pray that this campaign will help end Kony's efforts to steal, kill and destroy. But more importantly is the transformation only God can bring to the lives of the numerous children scarred by the actions of Kony and the LRA. Truthfully, if healing and forgiveness doesn't take precedence in the hearts of these former child soldiers, then we can expect revenge and hatred to rule and Kony's own victims to rise up in his place.

For more, read Keith McFarland's response to the video and campaign.

March 20, 2012

The Fear of Baptizing Children

As a credobaptist (one who believes in baptizing only professing believers), I find paedobaptism (baptizing the covenant children of believers) unpersuasive for numerous reasons: (1) there is no explicit mention of or instruction for paedobaptism in the NT; (2) paedobaptists assume without warrant that "household baptisms" mean that that there must have been infants in the households and ignore the fact that Peter "spoke the word to all . . . who were in his house" (Acts 16:32); (3) the practice of baptism was routinely connected with repentance and faith; (4) the theology of baptism requires repentance and faith—as Paul says, we are "buried with [Christ] in baptism" and "raised through faith" (Col. 2:12), and Peter virtually defines baptism as "as an appeal to God for a good conscience" (1 Pet. 3:21); (5) entrance into the covenant people of God is by spiritual birth, not physical birth—the design of which is that all who belong to God's covenant people truly know him (Heb. 8:11).

But that's not the point of this post. If we assume that credobaptism is the NT understanding of baptism, then we are faced with the question of the age at which our children should be baptized.

A recent post by Julian Freeman expresses my own position. He argues that in these intra-credobaptist discussions, we are fearing the wrong thing: namely, the fear that we might be wrong. As he expresses the question: "What if we baptize someone who ends up not really being converted? Then what?'

He gives two reasons that this is the wrong question to ask:

First, we should not be afraid of getting it wrong, because even the apostles did. Have you ever noticed how many people apostasize in the New Testament? How many of Paul's partners in ministry turned away (1 Tim 1.18-20; 2 Tim 4.10, 16)? And what of the disaster that was Simon Magus (Acts 8.9-24)? Certainly all of these had been baptized.

Second, we should not be afraid of getting it wrong because we are not charged with 'getting it right' in the first place. We're never called to be the police of baptism, ensuring that only those who give good enough proof get in the pool. We're called to baptize and disciple all who give profession of faith in Jesus as the risen Lord and Master of their lives.

Think about it; how much credible evidence could the people in Acts have given who heard one gospel message and were saved? Yet, they were baptized. Then discipled. And those who, in the process of discipleship, proved that their conversion was not genuine were disciplined out of the church. The answer is not to make sure people are converted before baptism, but after, in the context of local church membership, where they can be discipled and taught to obey King Jesus, with a strong dose of accountability, as part of a community.

This is where I think our ecclesiological paradigms can take us down the wrong path. A certain position fits the paradigm, but the exegetical evidence is completely lacking. I would put "do not baptize someone until you have years of observing fruits of repentance" in that category. I'd also put "do not share the Lord's Table with someone who has not been baptized as a believer" in this category. In the "system," these make sense. But they cannot be squared, in my opinion, with bigger and clearer principles in the NT (namely, baptize upon a credible profession of faith; share the Table with all who have been baptized in Jesus).

Julian goes on to identify some of the things we should be fearing in our practice of baptizing people:

Rather than a fear of 'getting it wrong' with someone (and then introducing somewhat arbitrary qualifications of age and genuine proof of conversion), we should be fearing suffocating baby Christians. And this is a real danger.

Here's what I mean: The enjoyment of means of grace in the life of a Christian are like breathing and the grace itself is the believer's oxygen. Without means of grace there will be no intake of oxygen. What we seriously need to ask ourselves is this: Is baptism a means of grace or not? Because if it is, we're essentially telling the youngest of baby Christians (new converts of whatever age) to continue living without breathing, without taking in grace through God's appointed means.

And it gets worse. Since proper baptist doctrine withholds participation in the Lord's Supper, membership, and pastoral oversight to those who have already been baptized as believers, we're withholding just about every corporate means of grace from this infant believer. And then we tell them to 'prove' their life in Christ, all the while denying them the oxygen their growth and life so desperately needs.

That is something we should genuinely fear.

At the end of the day, we have to remember that Jesus told his adult disciples to have faith like a child. Then many of us turn around and tell our children that their faith is not worthy of baptism until they have faith like an adult.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers