Justin Taylor's Blog, page 185

October 24, 2012

Obscure Writing Is Not Evidence of Profound Thinking

The two main principles of Joseph Williams’ Style: The Basics of Clarity and Grace are (1) it is good to write clearly and (2) anyone can.

But not everyone agrees with the first premise.

One of the reasons this happens is that when we “read about a complex subject written in a complex style, we too easily assume that such complexity signals deep thought, and so we try to imitate it, compounding our already confused writing.”

Take for example, the following quote from theologian John Milbank. Now it may actually be “deep”—but it’s hard to know because this 128-word sentence is almost incomprehensible in its verbosity and complexity:

But since “return to self” is not after all quite perfectly reflexive at that point at which it must also seek to be a return to its own higher origin, which is inseparable from its inner selfhood, one can see that self reflection (as Plotinus already taught) is equally a “failed” attempt (though this failure has the positive value of apophasis) at perfection reflection, which in its “failure” constructs the world beneath the psyche and it thereby the “giving” to be of material reality in its diverse modes—even though, for Proclus already, this is the work of higher not human souls, since the latter are rather “fully descended” into the body (and therefore have their realm of donation within the realm of the imagination, culture and history).

But the “turgid style” is by no means unique to theologians. Williams also cites laments from critics of several disciplines.

On the language of the social sciences

“A turgid and polysyllabic prose does seem to prevail in the social sciences. . . . Such a lack of intelligibility, I believe, usually has little or nothing to do with the complexity of thought. It has to do almost entirely with certain confusions of the academic writer about his own status.”

—C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination

On the language of medicine:

“It now appears that obligatory obfuscation is a firm tradition within the medical profession. . . . [Medical writing] is a highly skilled, calculated attempt to confuse the reader. . . . A doctor feels he might get passed over for an assistant professorship because he wrote his papers too clearly—because he made his ideas seem too simple.”

—Michael Crichton, New England Journal of Medicine

On the language of the law:

“In law journals, in speeches, in classrooms and in courtrooms, lawyers and judges are beginning to worry about how often they have been misunderstood, and they are discovering that sometimes they cannot even understand each other.”

—Tom Goldstein, New York Times

Why not follow the counsel of intellectuals like C.S. Lewis and George Orwell who knew how to communicate with clarity and grace? Lewis wrote in Letters to Children, p. 64:

Always try to use the language so as to make quite clear what you mean and make sure your sentence couldn’t mean anything else.

Always prefer the plain direct word to the long, vague one. Don’t implement promises, but keep them.

Never use abstract nouns when concrete ones will do. If you mean “More people died” don’t say “Mortality rose.”

In writing. Don’t use adjectives which merely tell us how you want us to feel about the things you are describing. I mean, instead of telling us the thing is “terrible,” describe it so that we’ll be terrified. Don’t say it was “delightful”; make us say “delightful” when we’ve read the description. You see, all those words (horrifying, wonderful, hideous, exquisite) are only like saying to your readers “Please, will you do my job for me.”

Don’t use words too big for the subject. Don’t say “infinitely” when you mean “very”; otherwise you’ll have no word left when you want to talk about something really infinite.

And here are Orwell’s elementary rules for using non-literary use of “language as an instrument for expressing and not for concealing or preventing thought.”

Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

Never use a long word where a short one will do.

If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

Never use the passive where you can use the active.

Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

October 23, 2012

Theology Is for Everyone

John Frame defines theology as “the application of the Word of God by persons to all areas of life.”

He defines application as “teaching” in the biblical sense of “the use of God’s revelation to meet the spiritual needs of people, to promote godliness and spiritual health.”

He sees five advantages to defining theology in this way:

“It gives a clear justification for the work of theology. . . . to remedy defects in ourselves, the hearers and readers of Scripture.”

“Theology in this sense . . . has a clear scriptural warrant: Scripture commands us to ‘teach’ in this way [Matt. 28:19f, etc.].”

“Despite its focus on human need, this definition does full justice to the authority and sufficiency of Scripture. Sola scriptura does not require that human needs be ignored in theology, only that Scripture have the final say about the answers to those needs (and about the propriety of the questions presented.)”

“Theology is thus freed from any false intellectualism or academicism. It is able to use scientific methods and academic knowledge where they are helpful, but it can also speak in nonacademic ways, as Scripture itself does—exhorting, questioning, telling parables, fashioning allegories and poems and proverbs and songs, expressing love, joy, patience . . . the list is without limit.”

“This definition enables us to make use of data from natural revelation and from man himself, not artificially separating the three ‘perspectives’ [normative, situational, existential].”

But if application basically means “teaching,” why doesn’t Frame just use that word? He admits there is nothing sacrosanct about the term application, but he wants “to discourage a certain false distinction between ‘meaning’ and ‘application’” that he believes “has resulted in much damage to God’s people.” He explains:

Every request for “meaning” is a request for an application because whenever we ask for the “meaning” of a passage we are expressing a lack in ourselves, an ignorance, an inability to use the passage.

Asking for “meaning” is asking for an application of Scripture to a need; we are asking Scripture to remedy that lack, that ignorance, that inability.

Similarly, every request for an “application” is a request for meaning; the one who asks doesn’t understand the passage well enough to use it himself.

Frame also writes that “the work of theology is not to discover some truth-in-itself in abstraction from all that is human; it is to take the truth of Scripture and humbly to serve God’s people by teaching and preaching it and by counseling and evangelizing.”

He is not seeking to disparage theoretical work done by professional theology, but he is “seeking to discourage the notion that theology is ‘properly’ something theoretical, something academic, as opposed to the practical teaching that goes on in preaching, counselling, and Christian friendship.”

For his full discussion and defense, see The Doctrine of the Knowledge of God (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1987), pp. 81-85.

Three New Podcasts Worth Listening To

The Gospel Coalition’s Going Deeper with TGC has two goals: (1) to follow up on the most widely read, controversial, helpful, insightful resources produced by our council members, writers, editors, and bloggers; (2) to serve you by using a different medium, audio, to provide the same quality of gospel-centered content we publish in blogs, essays, and reviews. Co-hosted by Collin Hansen (editorial director of TGC) and Mark Mellinger (news anchor of WANE-TV in Fort Wayne, IN).

Authors on the Line connects listeners to today’s best Christian writing. The podcast explores significant theological themes and relevant current events with the authors of important Christian books. Produced by Desiring God, hosted by Tony Reinke, author of Lit! A Christian Guide to Reading Books.

Theology Refresh is a podcast for Christian leaders hosted by David Mathis, executive editor for John Piper and Desiring God. The podcast aims to refresh and sharpen spiritual leaders on key aspects of Christian theology for application to everyday ministry.

October 22, 2012

It’d Be Nice to Hear a Pro-Life Politician Answer the Religion and Abortion Question This Way

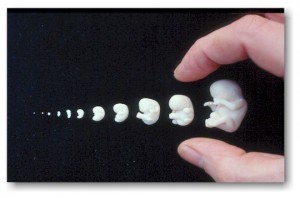

Saying that life begins at conception isn’t a controversial statement. It’s a question of science. Ask any embryologist and he can tell you that what’s growing in the mother’s womb is a whole, living, human boy or girl at his or her earliest stage of development, with his or her own unique DNA that will remain the same through all stages of development, from conception to death.

What’s controversial is that I think every human being is valuable simply because he or she is a member of the valuable human race. I don’t think human beings have to earn their rights by having certain characteristics like the “correct” race, or gender, or size, or ability, or age.

In other words, it’s the fact that I think we ought to be upholding universal human rights that’s the controversial position.

Now as a Christian, I do believe it’s my duty to protect the natural rights of human beings—to protect universal human rights—because human beings are the kind of being that’s valuable. But one doesn’t have to be a Christian to agree with universal human rights. There are many people of other religions, or no religion, who also want to uphold universal human rights.

The idea that we’re all created equal and equally possess unalienable rights regardless of our differences (race, size, age, ability, etc.) is a founding principle of this nation. Sadly, in the past, we allowed the government to define some human beings out of the human family by requiring they have certain preferred characteristics (like white skin) in order to qualify for protection.

Our failures in the past to hold our government accountable to our professed principle of unalienable rights for every human being led to serious human rights violations. I don’t want to repeat that same mistake. Instead, I would like to hold us to that founding principle.

You asked for a personal answer, and I agree that there are many emotions involved on all sides of this question. But I don’t want to confuse the issue by giving the impression that this is a matter of personal preference. Regulating subjective preferences is not the role of government, so answering as if the abortion issue were merely personal wouldn’t clarify what’s at stake. The issue of human rights is a public issue, and the protection of the lives of human beings is an area of public life that requires the government’s involvement.

Amen.

October 19, 2012

A New Great Books Program from a God-Centered Perspective

John Piper and Joe Rigney talk about the new “History of Ideas” undergraduate major at Bethlehem College & Seminary:

In the following video, John Piper explains his dream for BCS, his role at the school, and his plea for others to support the school (and note the 2012 Challenge Grand Initiative).

I happily serve on the board of trustees for this school because I believe so strongly in its vision and the people behind it, which makes it easy to commend to others for serious consideration.

The Apple Argument against Abortion

Peter Kreeft argues from a non-controversial premise to a controversial conclusion:

1. We Know What an Apple Is

Our first principle should be as undeniable as possible, for arguments usually go back to their first principles. If we find our first premise to be a stone wall that cannot be knocked down when we back up against it, our argument will be strong. Tradition states and common sense dictates our premise that we know what an apple is. Almost no one doubted this, until quite recently. Even now, only philosophers, scholars, “experts,” media mavens, professors, journalists, and mind-molders dare to claim that we do not know what an apple is.

2. We Really Know What an Apple Really Is

From the premise that “we know what an apple is,” I move to a second principle that is only an explication of the meaning of the first: that we really know what an apple really is. If this is denied, our first principle is refuted. It becomes, “We know, but not really, what an apple is, but not really.” Step 2 says only, “Let us not ‘nuance’ Step 1 out of existence!”

3. We Really Know What Some Things Really Are

From Step 2, I deduce the third principle, also as an immediate logical corollary, that we really know what some things (other things than apples) really are. This follows if we only add the minor premise that an apple is another thing.

This third principle, of course, is the repudiation of skepticism. The secret has been out since Socrates that skepticism is logically self-contradictory. To say “I do not know” is to say “I know I do not know.” Socrates’s wisdom was not skepticism. He was not the only man in the world who knew that he did not know. He had knowledge; he did not claim to have wisdom. He knew he was not wise. That is a wholly different affair and is not self-contradictory. All forms of skepticism are logically self-contradictory, nuance as we will.

All talk about rights, about right and wrong, about justice, presupposes this principle that we really know what some things really are. We cannot argue about anything at all—anything real, as distinct from arguing about arguing, and about words, and attitudes—unless we accept this principle. We can talk about feelings without it, but we cannot talk about justice. We can have a reign of feelings—or a reign of terror—without it, but we cannot have a reign of law.

4. We Know What Human Beings Are

Our fourth principle is that we know what we are. If we know what an apple is, surely we know what a human being is. For we aren’t apples; we don’t live as apples, we don’t feel what apples feel (if anything). We don’t experience the existence or growth or life of apples, yet we know what apples are. A fortiori, we know what we are, for we have “inside information,” privileged information, more and better information.

We obviously do not have total, or even adequate, knowledge of ourselves, or of apples, or (if we listen to Aquinas) of even a flea. There is obviously more mystery in a human than in an apple, but there is also more knowledge. I repeat this point because I know it is often not understood: To claim that “we know what we are” is not to claim that we know all that we are, or even that we know adequately or completely or with full understanding anything at all of what we are. We are a living mystery, but we also know much of this mystery. Knowledge and mystery are no more incompatible than eating and hungering for more.

5. We Have Human Rights Because We Are Human

The fifth principle is the indispensable, common-sensical basis for human rights: We have human rights because we are human beings.

We have not yet said what human beings are (e.g., do we have souls?), or what human rights are (e.g., do we have the right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”?), only the simple point that we have whatever human rights we have because we are whatever it is that makes us human.

This certainly sounds innocent enough, but it implies a general principle. Let’s call that our sixth principle.

6. Morality Is Based on Metaphysics

Metaphysics means simply philosophizing about reality. The sixth principle means that rights depend on reality, and our knowledge of rights depends on our knowledge of reality.

By this point in our argument, some are probably feeling impatient. These impatient ones are common-sensical people, uncorrupted by the chattering classes. They will say, “Of course. We know all this. Get on with it. Get to the controversial stuff.” Ah, but I suspect we began with the controversial stuff. For not all are impatient; others are uneasy. “Too simplistic,” “not nuanced,” “a complex issue”—do these phrases leap to mind as shields to protect you from the spear that you know is coming at the end of the argument?

The principle that morality depends on metaphysics means that rights depend on reality, or what is right depends on what is. Even if you say you are skeptical of metaphysics, we all do use the principle in moral or legal arguments. For instance, in the current debate about “animal rights,” some of us think that animals do have rights and some of us think they don’t, but we all agree that if they do have rights, they have animal rights, not human rights or plant rights, because they are animals, not humans or plants. For instance, a dog doesn’t have the right to vote, as humans do, because dogs are not rational, as humans are. But a dog probably does have a right not to be tortured. Why? Because of what a dog is, and because we really know a little bit about what a dog really is: We really know that a dog feels pain and a tree doesn’t. Dogs have feelings, unlike trees, and dogs don’t have reason, like humans; that’s why it’s wrong to break a limb off a dog but it’s not wrong to break a limb off a tree, and that’s also why dogs don’t have the right to vote but humans do.

7. Moral Arguments Presuppose Metaphysical Principles

The main reason people deny that morality must (or even can) be based on metaphysics is that they say we don’t really know what reality is, we only have opinions. They point out, correctly, that we are less agreed about morality than science or everyday practical facts. We don’t differ about whether the sun is a planet or whether we need to eat to live, but we do differ about things like abortion, capital punishment, and animal rights.

But the very fact that we argue about it—a fact the skeptic points to as a reason for skepticism—is a refutation of skepticism. We don’t argue about how we feel, about subjective things. You never hear an argument like this: “I feel great.” “No, I feel terrible.”

For instance, both pro-lifers and pro-choicers usually agree that it’s wrong to kill innocent persons against their will and it’s not wrong to kill parts of persons, like cancer cells. And both the proponents and opponents of capital punishment usually agree that human life is of great value; that’s why the proponent wants to protect the life of the innocent by executing murderers and why the opponent wants to protect the life even of the murderer. They radically disagree about how to apply the principle that human life is valuable, but they both assume and appeal to that same principle.

8. Might Making Right

All these examples so far are controversial. How to apply moral principles to these issues is controversial. What is not controversial, I hope, is the principle itself that human rights are possessed by human beings because of what they are, because of their being—and not because some other human beings have the power to enforce their will. That would be, literally, “might makes right.” Instead of putting might into the hands of right, that would be pinning the label of “right” on the face of might: justifying force instead of fortifying justice. But that is the only alternative, no matter what the political power structure, no matter who or how many hold the power, whether a single tyrant, or an aristocracy, or a majority of the freely voting public, or the vague sentiment of what Rousseau called “the general will.” The political form does not change the principle. A constitutional monarchy, in which the king and the people are subject to the same law, is a rule of law, not of power; a lawless democracy, in which the will of the majority is unchecked, is a rule of power, not of law.

9. Either All Have Rights or Only Some Have Rights

The reason all human beings have human rights is that all human beings are human. Only two philosophies of human rights are logically possible. Either all human beings have rights, or only some human beings have rights. There is no third possibility. But the reason for believing either one of these two possibilities is even more important than which one you believe.

Suppose you believe that all human beings have rights. Do you believe that all human beings have rights because they are human beings? Do you dare to do metaphysics? Are human rights “inalienable” because they are inherent in human nature, in the human essence, in the human being, in what humans, in fact, are? Or do you believe that all human beings have rights because some human beings say so—because some human wills have declared that all human beings have rights? If it’s the first reason, you are secure against tyranny and usurpation of rights. If it’s the second reason, you are not. For human nature doesn’t change, but human wills do. The same human wills that say today that all humans have rights may well say tomorrow that only some have rights.

10. Why Abortion Is Wrong

Some people want to be killed. I won’t address the morality of voluntary euthanasia here. But clearly, involuntary euthanasia is wrong; clearly, there is a difference between imposing power on another and freely making a contract with another. The contract may still be a bad one, a contract to do a wrong thing, and the mere fact that the parties to the contract entered it freely does not automatically justify doing the thing they contract to do. But harming or killing another against his will, not by free contract, is clearly wrong; if that isn’t wrong, what is?

But that’s what abortion is. Mother Teresa argued, simply, “If abortion is not wrong, nothing is wrong.” The fetus doesn’t want to be killed; it seeks to escape. Did you dare to watch The Silent Scream? Did the media dare to allow it to be shown? No, they will censor nothing except the most common operation in America.

11. The Argument From the Nonexistence of Nonpersons

Are persons a subclass of humans, or are humans a subclass of persons? The issue of distinguishing humans and persons comes up only for two reasons: the possibility that there are nonhuman persons, like extraterrestrials, elves, angels, gods, God, or the Persons of the Trinity, or the possibility that there are some nonpersonal humans, unpersons, humans without rights.

Traditional common sense and morality say all humans are persons and have rights. Modern moral relativism says that only some humans are persons, for only those who are given rights by others (i.e., those in power) have rights. Thus, if we have power, we can “depersonalize” any group we want: blacks, slaves, Jews, political enemies, liberals, fundamentalists—or unborn babies.

A common way to state this philosophy is the claim that membership in a biological species confers no rights. I have heard it argued that we do not treat any other species in the traditional way—that is, we do not assign equal rights to all mice. Some we kill (those that get into our houses and prove to be pests); others we take good care of and preserve (those that we find useful in laboratory experiments or those we adopt as pets); still others we simply ignore (mice in the wild). The argument concludes that therefore, it is only sentiment or tradition (the two are often confused, as if nothing rational could be passed down by tradition) that assigns rights to all members of our own species.

12. Three Pro-Life Premises and Three Pro-Choice Alternatives

We have been assuming three premises, and they are the three fundamental assumptions of the pro-life argument. Any one of them can be denied. To be pro-choice, you must deny at least one of them, because taken together they logically entail the pro-life conclusion. But there are three different kinds of pro-choice positions, depending on which of the three pro-life premises is denied.

The first premise is scientific, the second is moral, and the third is legal. The scientific premise is that the life of the individual member of every animal species begins at conception. (This truism was taught by all biology textbooks before Roe and by none after Roe; yet Roe did not discover or appeal to any new scientific discoveries.) In other words, all humans are human, whether embryonic, fetal, infantile, young, mature, old, or dying.

The moral premise is that all humans have the right to life because all humans are human. It is a deduction from the most obvious of all moral rules, the Golden Rule, or justice, or equality. If you would not be killed, do not kill. It’s just not just, not fair. All humans have the human essence and, therefore, are essentially equal.

The legal premise is that the law must protect the most basic human rights. If all humans are human, and if all humans have a right to life, and if the law must protect human rights, then the law must protect the right to life of all humans.

If all three premises are true, the pro-life conclusion follows. From the pro-life point of view, there are only three reasons for being pro-choice: scientific ignorance—appalling ignorance of a scientific fact so basic that nearly everyone in the world knows it; moral ignorance—appalling ignorance of the most basic of all moral rules; or legal ignorance—appalling ignorance of one of the most basic of all the functions of law. But there are significant differences among these different kinds of ignorance.

Scientific ignorance, if it is not ignoring, or deliberate denial or dishonesty, is perhaps pitiable but not morally blame-worthy. You don’t have to be wicked to be stupid. If you believe an unborn baby is only “potential life” or a “group of cells,” then you do not believe you are killing a human being when you abort and might have no qualms of conscience about it. (But why, then, do most mothers who abort feel such terrible pangs of conscience, often for a lifetime?)

Most pro-choice arguments, during the first two decades after Roe, disputed the scientific premise of the pro-life argument. It might be that this was almost always dishonest rather than honest ignorance, but perhaps not, and at least it didn’t directly deny the essential second premise, the moral principle. But pro-choice arguments today increasingly do.

Perhaps pro-choicers perceive that they have no choice but to do this, for they have no other recourse if they are to argue at all. Scientific facts are just too clear to deny, and it makes no legal sense to deny the legal principle, for if the law is not supposed to defend the right to life, what is it supposed to do? So they have to deny the moral principle that leads to the pro-life conclusion. This, I suspect, is a vast and major sea change. The camel has gotten not just his nose, but his torso under the tent. I think most people refuse to think or argue about abortion because they see that the only way to remain pro-choice is to abort their reason first. Or, since many pro-choicers insist that abortion is about sex, not about babies, the only way to justify their scorn of virginity is a scorn of intellectual virginity. The only way to justify their loss of moral innocence is to lose their intellectual innocence.

If the above paragraph offends you, I challenge you to calmly and honestly ask your own conscience and reason whether, where, and why it is false.

13. The Argument from Skepticism

The most likely response to this will be the charge of dogmatism. How dare I pontificate with infallible certainty, and call all who disagree either mentally or morally challenged! All right, here is an argument even for the metaphysical skeptic, who would not even agree with my very first and simplest premise, that we really do know what some things really are, such as what an apple is. (It’s only after you are pinned against the wall and have to justify something like abortion that you become a skeptic and deny such a self-evident principle.)

Roe used such skepticism to justify a pro-choice position. Since we don’t know when human life begins, the argument went, we cannot impose restrictions. (Why it is more restrictive to give life than to take it, I cannot figure out.) So here is my refutation of Roe on its own premises, its skeptical premises: Suppose that not a single principle of this essay is true, beginning with the first one. Suppose that we do not even know what an apple is. Even then abortion is unjustifiable.

Let’s assume not a dogmatic skepticism (which is self-contradictory) but a skeptical skepticism. Let us also assume that we do not know whether a fetus is a person or not. In objective fact, of course, either it is or it isn’t (unless the Court has revoked the Law of Noncontradiction while we were on vacation), but in our subjective minds, we may not know what the fetus is in objective fact. We do know, however, that either it is or isn’t by formal logic alone.

A second thing we know by formal logic alone is that either we do or do not know what a fetus is. Either there is “out there,” in objective fact, independent of our minds, a human life, or there is not; and either there is knowledge in our minds of this objective fact, or there is not.

So, there are four possibilities:

The fetus is a person, and we know that; The fetus is a person, but we don’t know that; The fetus isn’t a person, but we don’t know that;

The fetus isn’t a person, and we know that. What is abortion in each of these four cases?

In Case 1, where the fetus is a person and you know that, abortion is murder. First-degree murder, in fact. You deliberately kill an innocent human being.

In Case 2, where the fetus is a person and you don’t know that, abortion is manslaughter. It’s like driving over a man-shaped overcoat in the street at night or shooting toxic chemicals into a building that you’re not sure is fully evacuated. You’re not sure there is a person there, but you’re not sure there isn’t either, and it just so happens that there is a person there, and you kill him. You cannot plead ignorance. True, you didn’t know there was a person there, but you didn’t know there wasn’t either, so your act was literally the height of irresponsibility. This is the act Roe allowed.

In Case 3, the fetus isn’t a person, but you don’t know that. So abortion is just as irresponsible as it is in the previous case. You ran over the overcoat or fumigated the building without knowing that there were no persons there. You were lucky; there weren’t. But you didn’t care; you didn’t take care; you were just as irresponsible. You cannot legally be charged with manslaughter, since no man was slaughtered, but you can and should be charged with criminal negligence.

Only in Case 4 is abortion a reasonable, permissible, and responsible choice. But note: What makes Case 4 permissible is not merely the fact that the fetus is not a person but also your knowledge that it is not, your overcoming of skepticism. So skepticism counts not for abortion but against it. Only if you are not a skeptic, only if you are a dogmatist, only if you are certain that there is no person in the fetus, no man in the coat, or no person in the building, may you abort, drive, or fumigate.

This undercuts even our weakest, least honest escape: to pretend that we don’t even know what an apple is, just so we have an excuse for pleading that we don’t know what an abortion is.

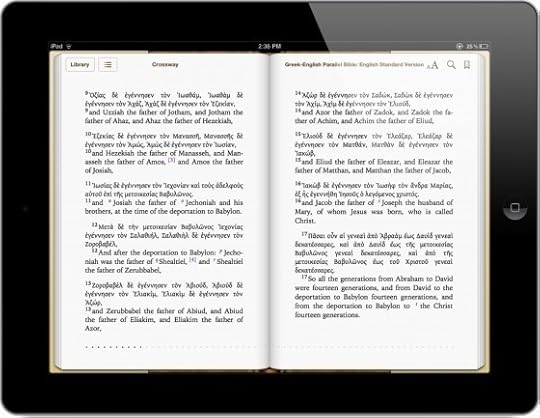

Two New Greek-ESV New Testaments from Crossway

Crossway will soon be carrying the new Nestle-Aland Greek text, 28th edition, with the English Standard Version (ESV) on facing pages.

Crossway will soon be carrying the new Nestle-Aland Greek text, 28th edition, with the English Standard Version (ESV) on facing pages.

It’s been 20 years since NA27 was released with a revised critical apparatus.

Amazon’s discount is currently listed as 40% off.

You can see a sample spread here.

Crossway is also publishing an e-Book only version of a Greek (NA27)-ESV Parallel New Testament. Instead of facing pages, the Greek and English are on parallel lines. It’s currently available.

You can see a screenshot below of what this might look like on your digital device:

October 18, 2012

Proof-Texting vs. Wise Application

CCEF’s David Powlison:

The phrase “Trust the Lord” is the deepest of all wise counsels. (The Scriptures call, invite, and command us to trust God in a hundred different ways. And God’s show-and-tell gives innumerable reasons to trust him. And the sins and sorrows of life are such that trust in God is our only hope.) But these words can be misused by “proof-texting” with a person who is struggling. Most of us have heard or overheard someone saying to a struggler, “You just need to trust the Lord,” as if that were all that needs to be said or can be said. Usually, more needs to be said for the relevance of this sweetest of counsels to be understood. Consider how this call, command, and exhortation can be used in a richer way that avoids the pitfall of “proof-texting.”

For example, scores of psalms call us to trust the Lord. As they do so, they always “locate” that call, so that it does not hang in a vacuum. They portray life’s troubles, inviting us to map our experience onto the psalmist’s experience. They recognize our temptation to forget God, to sin, or to be crushed under awareness of suffering or guilt. They reveal things about God that invite our heartfelt trust. They walk out how trusting God thinks, feels, talks, and acts. These details of how God meets us in our internal struggles and external troubles give the command a context. This makes the call to “trust the Lord” directly relevant and life-rearranging.

Or consider how Proverbs 29:25 puts things: “The fear of man lays a snare, but he who trusts the Lord is safe.” This sentence orients us to one of the heart’s instinctive disloyalties (we tend to take our cues from the opinions of other people). It orients us to the negative consequences of a false trust (life gets very complicated, tangled, and confused). It orients us to the Lord as the person in whom we will find flourishing and safety (the backdrop of promises and revelations of God in the rest of Scripture). And, by implication, many other significant factors can be reckoned with in learning how to take this passage to heart, e.g.,

the particular people or situations that you find difficult or intimidating,

the particular destructive emotions, thoughts, words, and actions that come forth when you misplace your core loyalty,

the particular ways that faith can now respond constructively to intimidating people and situations,

an understanding of your past that illumines when, how, and where patterns of fear of man became fixed characteristics,

an ability to anticipate future situations so that you can wisely and prayerfully plan how you want to respond,

the reasons for exceeding joy and gratitude as your Savior and Lord works to set you free of crippling patterns of fear.The application of this call to trust the Lord becomes meaningfully located in your entire life context.

Read the full thing, which contains definitions of both positive and negative proof-texting and how we should think about this.

Read the Same Biblical Passage from Multiple Perspectives

Luke 18:35-43:

As he drew near to Jericho, a blind man was sitting by the roadside begging. And hearing a crowd going by, he inquired what this meant. They told him, “Jesus of Nazareth is passing by.” And he cried out, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” And those who were in front rebuked him, telling him to be silent. But he cried out all the more, “Son of David, have mercy on me!” And Jesus stopped and commanded him to be brought to him. And when he came near, he asked him, “What do you want me to do for you?” He said, “Lord, let me recover my sight.” And Jesus said to him, “Recover your sight; your faith has made you well.” And immediately he recovered his sight and followed him, glorifying God. And all the people, when they saw it, gave praise to God.

Vern Poythress writes in Symphonic Theology:

[Ethics]

Suppose first that we read the passage to see what it says about ethics. There are no direct ethical statements in the passage, but we would certainly detect some general principles. We can say that (1) we ought to ask Jesus to supply our needs, as the blind man did; (2) we ought to have mercy on people in need as Jesus had mercy on the blind man; (3) we ought not to turn people away or discourage them from coming to Jesus, even if they are being a nuisance; (4) we ought to have faith in Jesus, as the blind man did; and (5) like the blind man and the crowd, we ought to praise God for his mighty works.

[Devotion]

Now suppose that we read the same passage again, this time with a devotional interest. We will probably recognize that Jesus’ healing of blindness is symbolic of his healing spiritual blindness (see especially John 9:39-41). Jesus has had mercy on us in saving us from spiritual blindness. As Christians we come to him again and again in prayer, just as the blind man did. We ask Jesus to take away our remaining blindness and cause us to see him as we should.

[Doctrine]

We might next read the passage for its theological doctrines. When we do so, we notice particularly what it reveals about Christ. His healing miracles testify to the fact that he is the divine Messiah. They also show the immeasurable power of God to work miracles in the physical world, as well as to work the miracle of spiritual sight and regeneration.

[Different Focuses of Attention]

And so we may go on to still other readings of the same passage, each time with a different focus of attention. Consequently, each time we may notice something new or something that did not realyy capture our attention before. If we are to sound the depths of a passage, we need to come back to it again and again.

If we read the passage from ten different perspectives, we still should not feel as if we are reading ten distinct passages. If we are reading carefully, we notice many of the same things each time. But each time certain different things stand out. Each time we force ourselves to pay direct attention to something new in order to make sure that we do not miss anything.

Thus, when we use a multitude of perspectives on a passage, we do not expect a conflict or contradiction between perspectives. Rather, we use each perspective to reinforce and enhance our total understanding.

October 17, 2012

Is an Embryo Like a Bean?

The New Yorker‘s Adam Gopnik, critiquing the metaphysics of a nickname used by Paul Ryan in talking about human life:

The New Yorker‘s Adam Gopnik, critiquing the metaphysics of a nickname used by Paul Ryan in talking about human life:

Ryan then went on to say something oddly disarming in its inherent lack of self-awareness. He talked about how, looking at a first sonogram of his daughter, he was thrilled by the beating heart in the tiny “bean” on the image, so much that he and his wife still call that child “Bean.”

As someone who is not often accused of being indifferent to the joys of fatherhood, I recognize the moment—and in fact still have that same early ultrasound picture, two of them. But Ryan’s moral intuition that something was indeed wonderful here was undercut, tellingly, by a failure to recognize accurately what that wonderful thing was, even as he named it: a bean is exactly what the photograph shows—a seed, a potential, a thing that might yet grow into something greater, just as a seed has the potential to become a tree. A bean is not a baby.

Ross Douthat responds with a model of how to cut through bad logic:

Gopnik is taking the congressman’s nickname for his unborn child and literalizing it—not, as he thinks, in the service of delivering some hard facts about the nature of life in utero, but in the service of obscuring those facts in the service of the pro-choice cause. On the one hand, calling an embryo a “bean” makes embryonic human life sound like a form of vegetative life — not an uncommon rhetorical move in these debates, but also one that collapses on the barest scrutiny. A bean is not remotely like a baby, certainly, but neither is a baby remotely like a full-grown bean plant, and that difference has a more obvious bearing on the debate over embryonic and fetal rights than the facile comparison between plant embryos and human ones. Outside of the world of level five veganism, neither the bean nor the plant have a strong moral claim on us, and it’s their essence as vegetables, rather than their level of development, that makes all the moral difference. Not even the most ardent enthusiast for the idea that ontology-recapitulates-phylogeny has ever argued that developing human life passes through a vegetablephase on its path toward full adulthood. Biologically speaking, we begin as we end up — which is one reason why any normal person would be rightly horrified to find the beans switched out for human embryos in their favorite cassoulet.

What’s more, even as a more indirect analogy the “bean” line is misleading, because it invites the reader to imagine the embryo in a kind of stasis — like a kidney bean in your cupboard or an acorn on the ground, awaiting favorable conditions to actually crack its shell and grow. It’s an image that evokes the old folk wisdom about “quickening,” which informed English common law on abortion in days before we knew much about what actually happens inside the womb. But if there’s anything that ultrasound technology has demonstrated beyond a shadow of a doubt, it’s that an embryo is “quick” long before the mother feels its movements. What Ryan saw on in the ultrasound photo is rather obviously a growing life—a shoot or a sapling, if you insist on pushing the tree analogy further, which doesn’t just have the “potential” to “grow into something greater.” No less than a newborn or a teenager, albeit at a much earlier stage, it is already in the process of growing into full maturity, and that process will necessarily continue unless someone intervenes to put a stop to it.

The rest of Gopnik’s piece offers a variation on the conventional pro-choice argument about the impossibility of knowing when a human life is finally “fully grown and when it isn’t”—or phrased more philosophically, when “the formed consciousness that distinguishes human life from bean life arises”—and why this uncertainty requires us to err on the side of (his words, not mine) “every woman for herself.” The broader argument-from-uncertainty is less implausible than the direct comparison of embryo to an acorn, but for a supposed champion of enlightenment the combination is still a strange one. In the name of science and progress, Gopnik is offering dubious embryology plus a view of human rights that’s essentially mysterian—abstracted from biological identity, agnostic about its own parameters, more comfortable evoking folk wisdom than reckoning with the science that’s replaced it. He’s draping himself the mantle of secular reason even as he talks misleadingly about biology and declares that some of the most crucial questions about justice, the law and human rights are eternally inaccessible to reason.

You can read the whole post here, which also gets into issues of the relationship between church and state, belief and policy.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers