Justin Taylor's Blog, page 177

December 17, 2012

I Bet You’ve Never Seen “Carol of the Bells” Like This Before

Joy to the World

Jamie Barnes and Brooks Ritter, preforming Sojourn Music’s arrangement of “Joy to the World” from their Advent Songs album.

HT: Matthew Robbins

A Reminder for Those Who Have Ministry Regrets at the End of 2012

Jeff Vanderstelt:

December 16, 2012

Screwtape’s Three-Step Plan for a War on Christmas

Image credit: thedailybeast.com

Michael Horton, penning a Screwtape letter to Wormwood:

You can’t do it all at once and you can’t do it one by one. You’ll have to work very hard to change the whole framework of a generation’s assumed convictions. The way you should do this won’t make sense at first, but I assure you that it works. You have to shift their habits of thinking from the more serious to the more trivial (without blowing your cover and provoking the opposite reaction). Affirm the second-best thing against the first-best, then the third-best against the second-best, and so on. Here’s what I mean.

First, encourage them to take their faith for granted, by relying on what others believe. Distract them from explicit concern to a foggy memory of slogans and phrases they learned in their nurseries. This shouldn’t be difficult. They’ve grown up in it, after all. The Enemy uses that to his benefit, so we should too. It doesn’t really matter if they assent to beliefs about the Trinity, the Incarnation, Atonement, Resurrection, and all, as long as they don’t know why they believe it or why it matters. Get them somehow to think that the Enemy is either too far away to really care about them or so near that he’s a harmless pet—even better, their own inner voice. But the important thing here is to dissuade them from reflecting on what happened—you know, the stuff you’ve heard about “Immanuel: God with us.”

Second, now that they have begun to take it all for granted and wear it lightly, affirm the importance of spirituality, feeling, and doing good to others. That’s already there in the Enemy’s speeches, of course, but separate all of this from the question of truth. If possible (and it is, I assure you), use these very “virtues” celebrated by the Enemy as weapons against the doctrine. As long as they keep him in their private experience, but don’t really think of the Enemy entering history and bringing “salvation” to “sinners,” we should have less trouble with them spreading their nonsense. Help them to shift the burden of their religion from public truth to personal experience and happiness. Then, once they run into some rough patches they’ll realize it doesn’t work. The key: just keep it all light and superficial. There should be plenty of good resources already available for that sort of thing. Soon, they’ll forget it altogether.

Third, now they’ll be ripe for an outright offensive strategy on your part. Now that the “weightiness” of the Enemy’s speeches have been drained from their daily routines, and they think, feel, and live more like us, attack the beliefs straight-on. They already wear them lightly, so, with a little sophistry, they shouldn’t be likely to hold onto them too dearly. At this point, though, while you’re doing this, be careful to assure them of the good that religion can do in the world. I know that it works against your grain, but it does work in the end. For example, make them deeply concerned to celebrate Christmas and Easter as cultural holidays. They really love Christmas. Puff the holiday, but add in all sort of other things that make it sentimental rather than serious. They can still have the trappings; the important thing at this stage is that they let go of what it meant. Maybe they’ll start thinking of the Enemy’s so-called “achievements” no longer as an announcement but as a philosophy for living, cultural values, and that sort of thing. Just get it out of the sphere of “Good News,” as some of them still call it. Again, there should be plenty of resources near at hand for you to use—especially look for ones that they produce themselves!

December 15, 2012

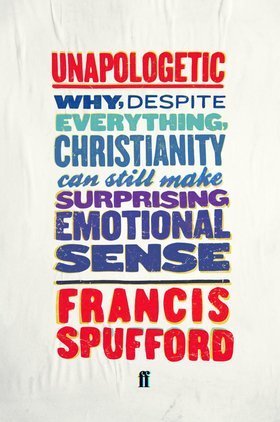

An Atheist Philosopher’s Book of the Year (by a Christian) and a Christian Theologian’s Book of the Year (by an Unbeliever)

Popular philosopher Alain de Botton writes that his favorite book of the year was a defense of Christianity:

Popular philosopher Alain de Botton writes that his favorite book of the year was a defense of Christianity:

This year, I was touched by Francis Spufford’s Unapologetic: Why, Despite Everything, Christianity Can Still Make Surprising Emotional Sense (Faber & Faber, £12.99). As a non-Christian, indeed a committed atheist, I was worried about how I’d feel about this book but it pulled off a rare feat: making Christianity seem appealing to those who have no interest in ever being Christians. A number of Christian writers have over the past decade tried to write books defending their faith against the onslaughts of the new atheists – but they’ve generally failed. Spufford understands that the trick isn’t to try to convince the reader that Christianity is true but rather to show why it’s interesting, wise and sometimes consoling.

I can’t figure out why the print and eBook remain unavailable from Amazon, but here is the link in case you want to secure it through a reseller.

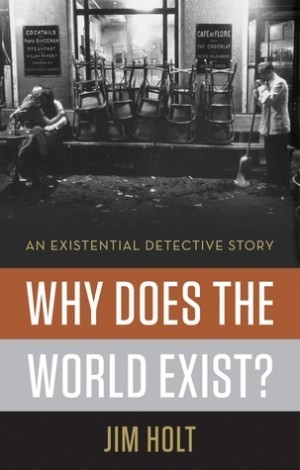

Christian pastor, author, and theologian Sam Storms, names Jim Holt’s Why Does the World Exist? An Existential Detective Story his book of the year. He writes:

Christian pastor, author, and theologian Sam Storms, names Jim Holt’s Why Does the World Exist? An Existential Detective Story his book of the year. He writes:

I wrestled for some time over how I should describe this book, and finally decided to let it describe itself. Here is the description it provides:

Of all the mysteries that humankind has confronted, the deepest and most persistent is the mystery of existence. Why should there be a universe at all, and why are we a part of it? Why is there Something rather than Nothing? . . . In Why Does the World Exist? Jim Holt takes on the role of cosmic gumshoe, exploring new and sometimes bizarre angles to the mystery of existence. His search for the ultimate explanation begins with the usual suspects—God versus the Big Bang. But as he proceeds to interrogate a distinguished and colorful series of witnesses—including the Nobel Laureate in Physics Steven Weinberg, the Christian theologian Richard Swinburne, the mathematical Platonist Roger Penrose, and even the late novelist John Updike—the list of ontological suspects begins to lengthen. Holt’s metaphysically intrepid investigation takes him from New York’s Greenwich Village to unlikely spots in Pittsburgh and Texas, and thence to London and ultimately to Oxford’s hallowed All Souls College. . . . Why Does the World Exist? is a rollicking medley of physics and philosophy, of theology and mathematics, of travel reportage and personal memoir.”

I know it seems strange that I should think so highly of a book written by an unbeliever, a man who at the end of his investigation refuses to acknowledge the existence of the God of the Bible as the only answer to his question. But this book actually turns out to be a marvelous, though unintended, apologetic for Christian monotheism. The reason is that again and again throughout his search Holt finds the explanations of philosophers, mathematicians, and physicists to be utterly devoid of consistency and persuasive power.

The simple fact is that such intellectuals have no way to account for why there is something rather than nothing. They know, and must finally admit, that their theories don’t work. So why won’t they (and Holt) simply concede the obvious: that a self-sufficient and eternal God created the Something? Because they don’t like Him! To acknowledge his existence and creative power is to come under his Lordship, both intellectually and morally, and they can’t bear the thought of it.

Holt is a long-time contributor to The New Yorker and is an excellent writer. I plan on reading this book several more times in the years to come. I hope you do too.

You can read the rest of Dr. Storms’s top 10 list after the jump:

(10) It all begins with a tie! I simply couldn’t bring myself to exclude either of these books, so I expanded my list from ten to eleven. Oddly enough, these two volumes both address the state of “religion” in America, but from differing perspectives.

In his book, Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics (New York: Free Press, 2012), 337 pp., New York Times columnist Ross Douthat makes a compelling case that our problem in the U.S. is neither too much religion nor intolerant secularism but rather bad religion, “the slow-motion collapse of traditional faith and the rise of a variety of pseudo-Christianities that stroke our egos, indulge our follies, and encourage our worst impulses. . . . Christianity’s place in American life has increasingly been taken over, not by atheism, Douthat argues, but by heresy: debased versions of Christian faith that breed hubris, greed, and self-absorption” (from the dustcover). The only bad thing about this book is that Douthat is right.

The other “tenth-best” book of the year is T. M. Luhrmann’s, When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012), 434 pp. There is a bit of a misnomer in the title, insofar as this massive and meticulous investigation into the dynamics of prayer and biblical spirituality focuses largely on the way it has come to expression in churches affiliated with the Vineyard. Other, non-charismatic, evangelicals will take umbrage at being identified with those whom she analyzes.

Tanya Luhrmann is a psychological anthropologist who teaches at Stanford. In order to write this book she attended two different Vineyard congregations (one in Chicago, the other in San Francisco), each for two years, and was deeply involved in the small group life at both churches. This isn’t a book review, but something needs to be said about what she does in its pages. Luhrmann seeks to account for the spiritual life, emotions, attitudes, and actions of charismatic Christians from a strictly psychological and social-scientific point of view. Her analysis of the claim of these believers to having heard the voice of God (hence the title) is based on hundreds of interviews and can be, at times, quite cynical. She critically parses out every word, belief, and cliché in the Vineyard world (although she also examines mainstream evangelicals such as Rick Warren and his Purpose Driven Life). Many will find her approach and conclusions offensive, but I was fascinated by this “confession” on the final page:

I have said that I do not presume to know ultimate reality. But it is also true that through the process of this journey, in my own way I have come to know God. I do not know what to make of this knowing. I would not call myself a Christian, but I find myself defending Christianity. (325)

(9) Jonathan Edwards, Charity and Its Fruits: Living in the Light of God’s Love, edited by Kyle Strobel (Wheaton: Crossway, 2012), 348 pp.

Wait a minute! Isn’t this supposed to be about books written in 2012, not in the 18th century? Well, yes, but this volume is more than merely what Edwards wrote. Kyle Strobel has provided us with a running commentary on Edwards’ famous exposition of 1 Corinthians 13 that makes this volume worth re-visiting time and time again. Although I chafe when I read Edwards’ failed attempt to defend cessationism, this is one of his best yet most neglected works. If for no other reason, get it to immerse yourself in the incomparable chapter, “Heaven Is a World of Love.” Here is what I wrote as an endorsement for the book:

As best I can tell, this is a first in Edwardsean studies. No one has done with Charity and Its Fruits what Kyle Strobel accomplishes here—providing us with an enlightening commentary and a readable text of one of Edwards’s most important, though highly neglected, treatises. All who love Edwards (and everyone should) will profit immensely from this exceptional volume.

(8) Journeys of Faith: Evangelicalism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Catholicism, and Anglicanism, edited by Robert L. Plummer (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2012), 256 pp.

This is a fascinating book that I highly recommend. If you want to know what these faiths entail, and especially why an individual who is committed to one makes the monumental decision to “convert” to another, this is the book for you. I enjoyed this book for another reason: I’m personally acquainted with several of the contributors. Wilbur Ellsworth, former pastor of First Baptist Church in Wheaton, Illinois, became an acquaintance of mine when I taught at Wheaton College. I had the privilege of preaching in his church (after he had left FBC) before he embraced Eastern Orthodoxy. Gregg Allison, who writes in response to Francis Beckwith (who returned to the Roman Catholic Church after many years as an evangelical Protestant), is a close personal friend. And I’m especially close to Lyle Dorsett who describes his journey into Anglicanism. I attended for four years the church where Lyle was senior pastor. Yes, I used to attend a charismatic Anglican church, and loved it (even though I was then, and remain to this day, a credo-baptist).

The contributors are all fair and balanced in their treatment of the others. I especially recommend this book to any Protestant who is being lured by Catholicism. Please get it and read Allison’s chapter.

(7) The Man Christ Jesus: Theological Reflections on the Humanity of Christ, by Bruce A. Ware (Wheaton: Crossway, 2012), 156 pp.

Although short, this book is long on fascinating insights into the humanity of Jesus. As evangelicals who rightfully defend the deity of Christ, we have at times acted as though any focus on his humanity was tantamount to yielding ground to theological liberals who believe he is nothing more than man. Ware’s book will go a long way in reversing this obvious gap in evangelical thinking about the person of Christ.

I should also mention that this book is not without controversy. Ware tackles the thorny question of whether or not Jesus could sin, which is to say, was he impeccable or peccable? All Bible-believing folk acknowledge that Jesus didn’t sin, but was it possible that he might have? Ware says no. I’m not so sure. Yet another volatile issue is the matter of Jesus being male. Could our Savior have been female? What role, if any, did the gender of Jesus play in our salvation? And the best part of this book is Ware’s defense of the thesis that Jesus lived and ministered not in the strength of his divine nature as God but through the Holy Spirit with whom he was filled, on whom he depended, and by whom he was empowered. You’ll love reading this book, even if you end up on the other side of such questions.

(6) The Hole in Our Holiness: Filling the Gap between Gospel Passion and the Pursuit of Godliness, by Kevin DeYoung (Wheaton: Crossway, 2012), 160 pp.

Here’s another short one from Crossway, but like Ware, DeYoung has hit a biblical home run. DeYoung writes with clarity and conviction and his prose is a delight to read. His ideas are, as Piper notes, “ruthlessly biblical” and, in my opinion, altogether persuasive. So what is the “hole” in our holiness? “The hole in our holiness,” says DeYoung, “is that we really don’t care much about it” (10). Yes, he explains why we don’t care and provides a plethora of biblical and practical reasons why we must. I loved this book! By the way, don’t hold your breath waiting for a year in which one of DeYoung’s books doesn’t appear on my top ten list!

(5) Engaging the Written Word of God, by J. I. Packer (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2012), 331 pp.

This book from J. I. Packer was published in 2012, but not written in it. It is a collection of Packer’s writings on Scripture drawn from a lengthy and incredibly productive ministry over the past forty years (Packer refers to it as a “mass of fugitive pieces”). These essays were first published in one volume in 1999 by Paternoster Press and I’m tremendously grateful to Hendrickson Publishers for releasing this newer and updated edition.

The book brings together the best of Packer on three primary topics relating to the Bible: biblical inerrancy (nine chapters), interpreting Scripture (seven chapters), and preaching the Word (seven chapters). Packer recently turned 86 years old and is still actively writing. If you are looking for a book that will cover the most essential themes relating to the Bible, you can do no better than to start with this one. Highly recommended!

(4) Sojourners and Strangers: The Doctrine of the Church, by Gregg R. Allison (Wheaton: Crossway, 2012), 494 pp.

Every time I ran into Gregg over the past several years I asked the same question: “When is your book on the church coming out?” Well, it’s finally here, and it was well worth the wait. Whereas the volumes by Ware and DeYoung, also from Crossway, were brief, this one is a substantive 494 pages. It covers virtually everything you’d want to know about the doctrine of the church, from church discipline to government, from Elders to ordinances, together with an excellent treatment of how spiritual gifts function in the body of Christ.

Perhaps the most controversial and intriguing part of the book is Allison’s rigorous (convincing?) defense of the multisite church model. I was honored when Gregg asked me to write an endorsement. Here is what I said:

No longer can one regard “evangelical ecclesiology” as a contradiction in terms. Among the many recent evangelical volumes on the doctrine of the church, Allison’s will undoubtedly prove to be the standard treatment for years to come. This excellent book is biblically faithful, historically informed, and pastorally relevant. One need not agree with Allison on every point of interpretation to profit immensely from his insights. I struggle to think of another volume on the subject that combines both theological depth and practical wisdom in such readable fashion as does Allison. I cannot recommend it too highly.

(3) The Intolerance of Tolerance, by D. A. Carson (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2012), 186 pp.

My greatest fear about this book by Carson is that it will go largely unread by many evangelicals, and especially by those non-evangelicals who most stand in need of its penetrating truths. It is a challenge to read but please don’t give up on it. The rich harvest is well worth the initial plowing.

So what does Carson mean by the “intolerance” of “tolerance”? He is using these terms to refer to a not so subtle shift in how people envision and define “tolerance”. The older “tolerance” referred to “accepting the existence of different views” (italics mine), whereas the newer “tolerance” has in mind the “acceptance of different views” (italics mine). Please don’t miss the distinction. Carson is pointing to the shift “from recognizing other people’s right to have different beliefs or practices to accepting the differing views of other people” (3). Again, “to accept that a different or opposing position exists and deserves the right to exist is one thing; to accept the position itself means that one is no longer opposing it. The new tolerance suggests that actually accepting another’s position means believing that position to be true, or at least as true as your own. We move from allowing the free expression of contrary opinions to the acceptance of all opinions; we leap from permitting the articulation of beliefs and claims with which we do not agree to asserting that all beliefs and claims are equally valid” (3-4).

Don’t think that Carson’s book is merely theoretical. He provides a vast array of examples and disturbing illustrations of this shift as seen in virtually every sphere of human activity. This is Carson at his best. Don’t pass it by.

[Choosing between number two and number one wasn't easy. After I go back and read both of them again (which I fully intend on doing), I may well flip-flop on my decision.]

(2) Jonathan Edwards on God and Creation, by Oliver D. Crisp (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 260 pp.

All I can say is “Wow!” Well, not really. I can actually say much more about this book. Oliver Crisp may well be the most informed and articulate theologian writing on Edwards in our day. He is Professor of Systematic Theology at Fuller Theological Seminary in California.

This is a demanding book, and those not already familiar with Edwards may find it a rough go. But Crisp is amazingly crisp (!) in his prose and has a remarkable knack at taking complex theological and philosophical ideas in Edwards and making sense of them for his readers. For those up-to-date on Edwardsean scholarship, Crisp both dedicates the book to Sang Hyun Lee and then proceeds to take him to task! I won’t go into what is involved here, other than to say that Crisp takes dead aim at and, in my opinion, successfully slays the interpretation of Edwards popularized by Lee. [I suppose it is important for you to know that the book on Edwards by McClymond and McDermott, which last year was number one on my list, defends Lee!]

On the back cover, Ken Minkema (Executive Editor and Director of the Jonathan Edwards Center at Yale University) writes the following: “Once every generation or so a book comes along that redefines prevailing interpretation of a figure or event. This is just such a book for understanding Edwards . . .” So, if you love Edwards, as I do, get this volume. You may not agree with how Crisp engages with Edwards (he actually has problems with Edwards’s concept of the Trinity) but you will, I trust, be challenged and led into breathless worship of the God whom Edwards proclaimed.

December 14, 2012

Why Do So Few Atheists Take Their Faith Seriously?

Last night at the Iron Works Church there was a moderated debate between Augustine and Bertrand Russell—more more accurately, Carl Trueman representing Augustine’s worldview of Christian orthodoxy vs. Chad Trainer (chairman of the board of the Bertrand Russell Society) representing Russell’s agnostic/atheistic worldview. This is a brilliant idea, and I’ll link to the video of the event when it’s available.

During the audience Q&A, a homeschooling mom asked how she could find satisfaction though she struggles with depression.

Trainer/Russell responded that the lady was doing valuable work, and that in 20 years she might well be satisfied with what she has accomplished.

But on the Reformation21 blog today, Trueman asks, “what basis had the man who said the following to claim that this mother was doing anything worthwhile at all?”

That man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins — all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand. Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built.

Trueman writes:

On Russell’s account, this mother is just one random bunch of atoms caring for some other random bunches of atoms. If so, any meaning is purely subjective. Why is satisfaction even an issue? To says she does something worthwhile is to assume some kind of fairy story that gives dignity to the whole and . . . simply makes life more bearable.

This is one reason why I find atheism so implausible. If Russell could dismiss Christianity in part because he had met so few Christians who seemed to take the faith seriously, I consider atheists to be much the same. Do not tell me that we are a random bunch of atoms and then try to impose your myths on me. Do not create a morality in your own image and then try to give it some objective, transcendent status. A random world does not give privileged status to the moral myths of an upper class English proto-hippy. Do not tell me that serial killers are morally worse than aid workers. At best, you might say that you find them personally more distasteful. If you are an atheist, have the courage to take heed of the words of Nietzsche’s Madman:

Have you ever heard of the madman who on a bright morning lighted a lantern and ran to the market-place calling out unceasingly: ‘I seek God! I seek God!’ As there were many people standing about who did not believe in God, he caused a great deal of amusement. Why! is he lost? said one. Has he strayed away like a child? said another. Or does he keep himself hidden? Is he afraid of us? Has he taken a sea-voyage? Has he emigrated? the people cried out laughingly, all in a hubbub. The insane man jumped into their midst and transfixed them with his glances. ‘Where is God gone?’ he called out. ‘I mean to tell you! We have killed him, you and I! We are all his murderers! But how have we done it? How were we able to drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the whole horizon? What did we do when we loosened this earth from its sun? Whither does it now move? Whither do we move? Away from all suns? Do we not dash on unceasingly? Backwards, sideways, forwards, in all directions? Is there still an above and below? Do we not stray, as through infinite nothingness? Does not empty space breathe upon us? Has it not become colder? Does not night come on continually, darker and darker? Shall we not have to light lanterns in the morning? Do we not hear the noise of the grave-diggers who are burying God? Do we not smell the divine putrefaction? –for even Gods putrefy! God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him! How shall we console ourselves, the most murderous of all murderers? The holiest and the mightiest that the world has hitherto possessed, has bled to death under our knife–who will wipe away the blood from us? With what water could we cleanse ourselves? What lustrums, what sacred games shall we have to devise? Is not the magnitude of this deed too great for us? Shall we not ourselves have to become Gods, merely to seem worthy of it? There never was a greater event–and on account of it, all who are born after us belong to a higher history than any history hitherto!’–Here the madman was silent and looked again at his hearers; they also were silent and looked at him in surprise. At last he threw his lantern on the ground, so that it broke in pieces and was extinguished. ‘I come too early,’ he then said, ‘I am not yet at the right time. This prodigious event is still on its way, and is traveling–it has not yet reached men’s ears. Lightning and thunder need time, the light of the stars needs time, deeds need time, even after they are done, to be seen and heard. This deed is as yet further from them than the furthest star–and yet they have done it!’

December 13, 2012

Why Brick-and-Mortar Research Libraries Still Matter in a Digital Age

The Law Library of the Iowa State Capitol (Des Moines)

Thomas Mann:

First, what significant research resources will you miss if you confine your research entirely, or even primarily, to sources available on the open Internet?

And second, what techniques of subject searching will you also miss if you confine yourself to the limited software and display mechanisms of the Internet?

As I will demonstrate, bricks-and-mortar research libraries contain vast ranges of printed books, copyrighted materials in a variety of other formats, and site-licensed subscription databases that are not accessible from anywhere, at anytime, by anybody on the Web. Moreover, many of these same resorouces allow avenues of subject access that cannot be matched by “relevance ranked” keyword searching.

One can reasonably say that libraries today routinely encompass the entire Internet—that is, they will customarily provide terminals allow free access to all of the open portions of the Net—but that the Internet does not, and cannot, contain more than a small fraction of everything discoverable within library walls.

—Thomas Mann, The Oxford Guide to Library Research: How to Find Reliable Information Online and Offline, 3d ed (Oxford University Press, 2005), xiii.

Calvin’s Pastoral Theology

Scott Manetsch, professor of church history at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, gave a lecture in June 2012 at the RCA Integrity leadership conference in Chicago. You can watch below his talk on “Calvin’s Pastoral Theology.”

HT: @TonyReinke

Here’s an outline of the talk:

1. Calvin: Reformer of the Genevan Church

2. Calvin: The Architect of the Genevan Church

3. Calvin’s Principles for Pastoral Ministry

The word of God is essential for spiritual reformation

Christian ministers have equal authority under Christ

Christian ministers are called to unceasing prayer

Christian ministers have primary responsibility to preach the gospel

Christian ministers must know and care for their people

Christian ministers employ church discipline as one important form of pastoral care

Dr. Manetsch is the author of the new book, Calvin’s Company of Pastors: Pastoral Care and the Emerging Reformed Church, 1536-1609 (Oxford University Press, 2013)—an expensive but groundbreaking tome full of primary research, using the unpublished (and rarely consulted) registers of Geneva’s Consistory.

Dr. Manetsch is the author of the new book, Calvin’s Company of Pastors: Pastoral Care and the Emerging Reformed Church, 1536-1609 (Oxford University Press, 2013)—an expensive but groundbreaking tome full of primary research, using the unpublished (and rarely consulted) registers of Geneva’s Consistory.

OUP’s description is below:

In Calvin’s Company of Pastors, Scott Manetsch examines the pastoral theology and practical ministry activities of Geneva’s reformed ministers from the time of Calvin’s arrival in Geneva until the beginning of the seventeenth century.

During these seven decades, more than 130 men were enrolled in Geneva’s Venerable Company of Pastors (as it was called), including notable reformed leaders such as Pierre Viret, Theodore Beza, Simon Goulart, Lambert Daneau, and Jean Diodati. Aside from these better-known epigones, Geneva’s pastors from this period remain hidden from view, cloaked in Calvin’s long shadow, even though they played a strategic role in preserving and reshaping Calvin’s pastoral legacy. These “forgotten” reformed pastors, together with Calvin himself, are the central characters of this book.

Making extensive use of archival materials, published sermons, catechisms, prayer books, personal correspondence, and theological writings, Manetsch offers an engaging and vivid portrait of pastoral life in sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Geneva, exploring the manner in which Geneva’s ministers conceived of their pastoral office and performed their daily responsibilities of preaching, public worship, moral discipline, catechesis, administering the sacraments, and pastoral care.

Along the way, a variety of important subsidiary questions are explored, including:

In what ways did the practice of preaching and church discipline change in Geneva after Calvin?

What were some of the different ways that lay people in Geneva responded to the ministers’ sermons and corrective discipline?

In what ways were the structure and practice of pastoral ministry in Geneva similar to or different from other Protestant churches during the period?

What can be learned about the ministers’ religious priorities and pastoral concerns from their published writings?

To what extent did Geneva’s religious leaders such as Beza, Daneau, and Goulart remain faithful to Calvin’s theological legacy and religious program?Manetsch demonstrates that Calvin and his colleagues were much more than “talking heads,” dispensing theological information to the people in their congregations. Rather, they saw themselves as spiritual shepherds of Christ’s Church, and this self-understanding shaped to a significant degree their daily work as pastors and preachers. This careful study of religious life in Geneva from 1536 to 1609 also shows that the clerical office in Geneva changed in subtle ways during the half-century after Calvin’s death, even as the Company of Pastors remained committed to the reformer’s pastoral vision.

Here is the table of contents:

Introduction

Geneva and Her Reformation

The Company of Pastors

Vocation and Ordination

The Pastor’s Household

Pastoral Rhythms

The Ministry of the Word

The Ministry of Moral Oversight

Pastors and their Books

The Ministry of Pastoral Care

A Theology of God’s Emotion

Kevin Vanhoozer on Rob Lister’s new book, God Is Impassible and Impassioned: Toward a Theology of Divine Emotion:

Kevin Vanhoozer on Rob Lister’s new book, God Is Impassible and Impassioned: Toward a Theology of Divine Emotion:

Rob Lister boldly goes where few evangelicals have gone before in this very helpful study of how best to make sense of what Scripture says about God’s emotions.

Lister does away with caricatures of the Patristic tradition as having sold out to Greek philosophy, surveys contemporary evangelical positions on divine impassibility, and provides a constructive hermeneutical method and theological model for doing justice both to the impassibilist tradition and to biblical language about divine emotions.

As G. K. Chesterton observes, ‘an inch is everything when you’re balancing,’ and to Lister’s credit he completes his routine without falling off the balance beam that is systematic theology.

You can read a sample of chapter 7 here: “Impassible and Impassioned: Toward a Theological Hermeneutic.”

December 12, 2012

10 Misconceptions about the New Testament Canon

Michael Kruger identifies 10 common misconceptions (or misunderstandings) about the origins and development of the NT Canon:

These are misconceptions that are not only held by the average layman, but are often shared by those in the academic community as well. It is always difficult to know how such misunderstandings develop and are promulgated. Sometimes they are just ideas that are repeated so often that no one bothers (anymore) to see if they have merit. In other cases, these ideas have been promoted through popular presentations of the canon’s origins (e.g., The Da Vinci Code). And in other cases, scholars have made sustained arguments for some of these positions (though, in my opinion, those arguments are not, in the end, convincing). Either way, it is time for these issues to be dusted off and reconsidered.

Here is his top 10:

The term “canon” can only refer to a fixed, closed list of books

Nothing in early Christianity dictated that there would be a canon

The New Testament authors did not think they were writing Scripture

New Testament books were not regarded as scriptural until around 200 A.D.

Early Christians disagreed widely over the books which made it into the canon

In the early stages, apocryphal books were as popular as the canonical books

Christians had no basis to distinguish heresy from orthodoxy until the fourth century

Early Christianity was an oral religion and therefore would have resisted writing things down

Athanasius’ Festal Letter (367 A.D.) is the first complete list of New Testament books

Dr. Kruger’s books include Canon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament Books, The Heresy of Orthodoxy: How Contemporary Culture’s Fascination with Diversity Has Reshaped Our Understanding of Early Christianity (co-authored with Andreas Kostenberger), and The Early Text of the New Testament (co-edited with Charles Hill).

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers