Justin Taylor's Blog, page 172

January 31, 2013

Did the Princetonians Neglect the Human Character of Scripture?

Here is an overlooked paragraph from Hodge and Warfield’s 1881 essay on “Inspiration“:

It must be remembered that it is not claimed that the Scriptures, any more than their authors, are omniscient. The information they convey is in the forms of human thought, and limited on all sides. They were not designed to teach philosophy, science or human history as such. They were not designed to furnish an infallible system of speculative theology. They are written in human languages, whose words, inflections, constructions and idioms bear everywhere indelible traces of human error. The record itself furnishes evidence that the writers were in large measure dependent for the their knowledge upon sources and methods in themselves fallible, and that their personal knowledge and judgments were in many matters hesitating and defective, or even wrong. Nevertheless, the historical faith of the Church has always been that all the affirmations of Scripture of all kinds, whether of spiritual doctrine or duty, or of physical or historical fact, or of psychological or physical principle, are without error when the ipsissima verba of the original autographs are ascertained and interpreted in their natural and intended sense.

January 30, 2013

If You Struggle with Evangelism

Thabiti Anyabwile shares about a recent trip home on a plane:

Thabiti Anyabwile shares about a recent trip home on a plane:

Security was easy at the Memphis airport. I dutifully boarded with the other sleepy passengers, quickly put my bag in the overhead compartment and took my seat. A few moments later a young woman asked to take her seat next to me. She carried a large bag (suitcase for the shoulder), a breakfast container and drink, and her iPad with ear phones dangling. I began reading my morning’s devotional on my iPad, secretly hoping I wouldn’t have a conversation but enough peace and quiet to read. Also heard the soft “good morning” of fear of man.

Before long I heard the announcement to turn off all electronic equipment. Still not sure why electronic gadgets cause so much trouble for pilots, I complied. Turned on the overhead light to read my book. But the yellow tint in the dark cabin was useless even when she graciously tried to turn her light in my direction as well. Nothing left to do, we began to talk. Two minutes into the conversation I knew this was an opportunity, but I wasn’t making a commitment. Maybe she was already a Christian? Maybe she would be like so many other passengers who complete the pleasantries and prefer sleep? Maybe the sun would come up or the cabin lights brighten and we’d silently expect the other to turn to their electronics? So many maybes.

But none of those things happened. Instead, she began to talk.

Read the whole thing here.

January 29, 2013

Dialoguing with a Gay Activist Who Hates the “Hate the Sin but Love the Sinner” Distinction

Peter Kreeft recalls a conversation he once had:

My teacher was an articulate homosexual activist who was arguing, at Boston College, that “Catholic” and “gay” are as compatible as ham and eggs. I respected the clarity and intelligence of his mind and the openness and apparent goodwill of his heart, so I hoped that our conversation might open and clarify both our minds and teach us something new. (This almost never happens when these two sides argue about this subject.)

I was not disappointed.

I shall try and reconstruct our dialogue with a minimum of additions and polishings, as I like to believe Plato did to Socrates in his early dialogues. For purposes of anonymity, I shall call my dialogue partner “Art.”

PETER: Art, I’m really curious about one point of your argument, one part I just don’t understand. And I believe in listening before arguing, as you said you do. So I’m not trying to argue now—that’s not the point of my question—but first of all to listen and to understand. OK?

ART: Of course. What’s the point you don’t understand?

PETER: Well, to explain that, I have to ask you to listen too, to where I’m coming from.

ART: And where’s that?

PETER: Just the teachings of the Bible and the Church, all of them. I know you don’t believe all of them, only some. But I do. So from my point of view, what you do, and what you justify doing, is a sin. That’s the label you reject, right?

ART: Right. So what don’t you understand?

PETER: Please don’t take this as a personal insult, or even an argument, but I know of no other way of phrasing it than with biblical language, which you will probably find offensive. My question is this: Why are you guys the only class of sinners who not only deny that your sin is sin but insist on identifying yourself with it? We’re all sinners, in one way or another, and I’m not assuming your sins are worse than mine, but at least I think I’m more than my sins, whatever they are. I love the sinner but hate the sin. But you don’t do you?

ART: No, I don’t. What I hate is that hypocritical distinction.

PETER: Why?

ART: Because when you attack homosexuality, you attack homosexuals. It’s that simple.

PETER: But alcoholics don’t say that the Church attacks alcoholics when she attacks alcoholism. And cowards don’t say that they are their cowardice. And murderers don’t say the church is hypocritical for condemning their sin but no them, the sinners. Adulterers don’t deny the distinction between the adulterer and the adultery. The only group of sinners I’ve ever heard of who do this is you. And it seems to me you all do that, you always say that. All gays say that. Don’t they?

ART: Yes, we do. And I forgive you for being to insensitive that you don’t realize that you’ve done right now what you defend the Church for doing: insulting and rejecting me, and not just what I do.

PETER: Wait a minute here! You’re saying that when I make that distinction between what you are and what you do, when I accept what you are as distinct from what you do, I’m rejecting what you are? How can I be rejecting what you are in accepting what you are?

ART: That’s exactly what you’re doing. In fact, you’re trying to kill me.

PETER: What? That’s crazy. Now you’re being paranoid.

ART: No, listen: In trying to separate what I do from what I am, you’re trying to separate my body from my soul, my sex life from my identity. That’s what you’re doing by insisting on that distinction. Your distinction between what you call the “sinner” and the “sin” is really death to me; it’s the separation of body and soul, deed and identity. I’m holding the two together; you’re trying to pull them apart, and that’s death.

PETER: That’s sophistical. That’s an argument that just doesn’t fit the facts. Look at the facts instead of the argument. This is what the church believes about you—what I believe about you: you can be a saint! You have dignity. The Church thinks more highly of you than you think of yourself. She loves your being more than you do; that’s why she hates your sins against your being. We believe your self is greater than your deeds, whatever they are. But you don’t.

ART: The Church and the Bible will tell me I’m an abomination to God.

PETER: No! Not in your person, only in your sins, just like the rest of us, like all of us. That’s Paul’s point in Romans 1. He’s condemning hypocritical condemnation of pagan homosexuals by straight Jews just as much as he’s condemning pagan homosexuality.

ART: The Church is my enemy.

PETER: The Church is your friend. Because the Church tells us two things about you, not just one, and she will never change either one, she never can change either one, because both are matters of unchangeable natural law, based on eternal law, based on the very nature of God. She can’t ever say that what you do is good for the same reason that she can’t ever say that what you are is bad. She defends your being just as absolutely as she attacks your lifestyle; she hates your cancer because she loves your body. It’s the same authority for both. The authority you hate when it condemns what you do is your only reliable ally in defending what you are. You want the Church to change her teaching on what you do, and you’re trying to put social pressure on her to do that, but if she did that, then she could change her teaching on what you are, too, for the same reason, under social pressures. I’m sure you know that the old social pressures to hate homosexuals are far from dead. You know what happened in Hitler’s Germany. You know how changeable and fickle mankind is—and how dangerous. When the last bastion of absolute moral law is compromised, when even the Church bends to the winds of social pressure, what shelters will you have then?

ART: I’m not worried about the Left; I’m worried about the Right.

PETER: Today, maybe, but what about tomorrow? Today the fashion is the be Leftist, but just a short time ago the fashion was from the Right, and tomorrow it may swing to the Right again, like a pendulum. You can’t rely on fashionable opinions to protect you. That’s building sandcastles. The tides always change and knock them down.

ART: I’ll take my chances, thank you. I don’t know what will happen in the future, I grant you that. But I know what’s happening now, and I can’t take that. We just can’t take your “love the sinner, hate the sin” distinction. That much we know.

PETER: You still haven’t explained to me why. I began by asking that question, and I really want an answer. I want to know what’s going on in your mind.

ART: OK, I think I can explain it to you. You say I shouldn’t feel threatened by that distinction, right?

PETER: Right.

ART: You say the Church tells me she loves me, even though she hates what I do, right?

PETER: Right.

ART: Well, suppose the shoe was on the other foot. Suppose you were in the minority. Suppose what you wanted to do was to have churches and sacraments and Bibles and prayers, and those in power said to you: “We hate that. We hate what you do. We will do all in our power to stop you from doing what you do. But we love you. We love what you are. We love Christians, we just hate Christianity. We love worshippers; we just hate worship. And we’re going to put every possible pressure on you to feel ashamed about worshipping and make you repent of your sin of worshiping. But we love you. We affirm your being. We just reject your doing.” Tell me, how would that make you feel? Would you accept their

distinction?

PETER: You know, I never thought of it that way. Thank you. You really did make me see things in a new way. You’re right. I would not be comfortable with that distinction. I would not be able to accept it. In fact, I would say pretty much what you just said: that you’re trying to kill my identity.

ART: See? Now you understand how we feel.

PETER: Yes, I think I do. Thank you very much for showing me that. But do you realize what you’ve just said? What you’ve just showed me?

ART: What do you mean?

PETER: You’ve said to me that sodomy is your religion.

Dialoging with a Gay Activist Who Hates the “Hate the Sin but Love the Sinner” Distinction

Peter Kreeft recalls a conversation he once had:

My teacher was an articulate homosexual activist who was arguing, at Boston College, that “Catholic” and “gay” are as compatible as ham and eggs. I respected the clarity and intelligence of his mind and the openness and apparent goodwill of his heart, so I hoped that our conversation might open and clarify both our minds and teach us something new. (This almost never happens when these two sides argue about this subject.)

I was not disappointed.

I shall try and reconstruct our dialogue with a minimum of additions and polishings, as I like to believe Plato did to Socrates in his early dialogues. For purposes of anonymity, I shall call my dialogue partner “Art.”

PETER: Art, I’m really curious about one point of your argument, one part I just don’t understand. And I believe in listening before arguing, as you said you do. So I’m not trying to argue now—that’s not the point of my question—but first of all to listen and to understand. OK?

ART: Of course. What’s the point you don’t understand?

PETER: Well, to explain that, I have to ask you to listen too, to where I’m coming from.

ART: And where’s that?

PETER: Just the teachings of the Bible and the Church, all of them. I know you don’t believe all of them, only some. But I do. So from my point of view, what you do, and what you justify doing, is a sin. That’s the label you reject, right?

ART: Right. So what don’t you understand?

PETER: Please don’t take this as a personal insult, or even an argument, but I know of no other way of phrasing it than with biblical language, which you will probably find offensive. My question is this: Why are you guys the only class of sinners who not only deny that your sin is sin but insist on identifying yourself with it? We’re all sinners, in one way or another, and I’m not assuming your sins are worse than mine, but at least I think I’m more than my sins, whatever they are. I love the sinner but hate the sin. But you don’t do you?

ART: No, I don’t. What I hate is that hypocritical distinction.

PETER: Why?

ART: Because when you attack homosexuality, you attack homosexuals. It’s that simple.

PETER: But alcoholics don’t say that the Church attacks alcoholics when she attacks alcoholism. And cowards don’t say that they are their cowardice. And murderers don’t say the church is hypocritical for condemning their sin but no them, the sinners. Adulterers don’t deny the distinction between the adulterer and the adultery. The only group of sinners I’ve ever heard of who do this is you. And it seems to me you all do that, you always say that. All gays say that. Don’t they?

ART: Yes, we do. And I forgive you for being to insensitive that you don’t realize that you’ve done right now what you defend the Church for doing: insulting and rejecting me, and not just what I do.

PETER: Wait a minute here! You’re saying that when I make that distinction between what you are and what you do, when I accept what you are as distinct from what you do, I’m rejecting what you are? How can I be rejecting what you are in accepting what you are?

ART: That’s exactly what you’re doing. In fact, you’re trying to kill me.

PETER: What? That’s crazy. Now you’re being paranoid.

ART: No, listen: In trying to separate what I do from what I am, you’re trying to separate my body from my soul, my sex life from my identity. That’s what you’re doing by insisting on that distinction. Your distinction between what you call the “sinner” and the “sin” is really death to me; it’s the separation of body and soul, deed and identity. I’m holding the two together; you’re trying to pull them apart, and that’s death.

PETER: That’s sophistical. That’s an argument that just doesn’t fit the facts. Look at the facts instead of the argument. This is what the church believes about you—what I believe about you: you can be a saint! You have dignity. The Church thinks more highly of you than you think of yourself. She loves your being more than you do; that’s why she hates your sins against your being. We believe your self is greater than your deeds, whatever they are. But you don’t.

ART: The Church and the Bible will tell me I’m an abomination to God.

PETER: No! Not in your person, only in your sins, just like the rest of us, like all of us. That’s Paul’s point in Romans 1. He’s condemning hypocritical condemnation of pagan homosexuals by straight Jews just as much as he’s condemning pagan homosexuality.

ART: The Church is my enemy.

PETER: The Church is your friend. Because the Church tells us two things about you, not just one, and she will never change either one, she never can change either one, because both are matters of unchangeable natural law, based on eternal law, based on the very nature of God. She can’t ever say that what you do is good for the same reason that she can’t ever say that what you are is bad. She defends your being just as absolutely as she attacks your lifestyle; she hates your cancer because she loves your body. It’s the same authority for both. The authority you hate when it condemns what you do is your only reliable ally in defending what you are. You want the Church to change her teaching on what you do, and you’re trying to put social pressure on her to do that, but if she did that, then she could change her teaching on what you are, too, for the same reason, under social pressures. I’m sure you know that the old social pressures to hate homosexuals are far from dead. You know what happened in Hitler’s Germany. You know how changeable and fickle mankind is—and how dangerous. When the last bastion of absolute moral law is compromised, when even the Church bends to the winds of social pressure, what shelters will you have then?

ART: I’m not worried about the Left; I’m worried about the Right.

PETER: Today, maybe, but what about tomorrow? Today the fashion is the be Leftist, but just a short time ago the fashion was from the Right, and tomorrow it may swing to the Right again, like a pendulum. You can’t rely on fashionable opinions to protect you. That’s building sandcastles. The tides always change and knock them down.

ART: I’ll take my chances, thank you. I don’t know what will happen in the future, I grant you that. But I know what’s happening now, and I can’t take that. We just can’t take your “love the sinner, hate the sin” distinction. That much we know.

PETER: You still haven’t explained to me why. I began by asking that question, and I really want an answer. I want to know what’s going on in your mind.

ART: OK, I think I can explain it to you. You say I shouldn’t feel threatened by that distinction, right?

PETER: Right.

ART: You say the Church tells me she loves me, even though she hates what I do, right?

PETER: Right.

ART: Well, suppose the shoe was on the other foot. Suppose you were in the minority. Suppose what you wanted to do was to have churches and sacraments and Bibles and prayers, and those in power said to you: “We hate that. We hate what you do. We will do all in our power to stop you from doing what you do. But we love you. We love what you are. We love Christians, we just hate Christianity. We love worshippers; we just hate worship. And we’re going to put every possible pressure on you to feel ashamed about worshipping and make you repent of your sin of worshiping. But we love you. We affirm your being. We just reject your doing.” Tell me, how would that make you feel? Would you accept their

distinction?

PETER: You know, I never thought of it that way. Thank you. You really did make me see things in a new way. You’re right. I would not be comfortable with that distinction. I would not be able to accept it. In fact, I would say pretty much what you just said: that you’re trying to kill my identity.

ART: See? Now you understand how we feel.

PETER: Yes, I think I do. Thank you very much for showing me that. But do you realize what you’ve just said? What you’ve just showed me?

ART: What do you mean?

PETER: You’ve said to me that sodomy is your religion.

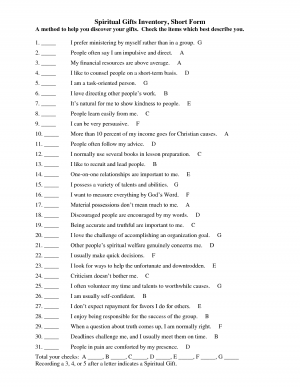

10 Reasons Why the Conventional View of “Spiritual Gifts” May Be Wrong

So argues Ken Berding in his book, What Are Spiritual Gifts? Rethinking the Conventional View.

So argues Ken Berding in his book, What Are Spiritual Gifts? Rethinking the Conventional View.

The conventional view is that the “spiritual gifts” (Eph. 4:11-12; Rom. 12:6-8; 1 Cor. 12:8-10, 28-30) are God-given special abilities that Christians are to discover and then use in ministry. Berding’s argument is that the spiritual gifts, understood contextually in Paul’s letters, are actually ministry assignments or roles, that is, the actual ministries themselves.

In an interview Dr. Berding gives some reasons for why he holds this view:

1. Many people assume that the Greek word charisma means special ability. This is a misunderstanding of how words work and confuses the discussion.

2. Paul’s central concern in Ephesians 4, Romans 12, and 1 Corinthians 12-14—the “spiritual gifts passages”—is that every believer fulfills his or her role in building up the community of faith. That’s what he’s writing about; that’s what he cares about. The Corinthians, not Paul, were the ones who were interested in special abilities.

3. Paul doesn’t use any ability concepts in his extended metaphor of the body in 1 Corinthians 12:12-27. His illustration is all about the roles—or the ministries—of the various members of the body.

4. The actual activities that Paul lists in Ephesians 4, Romans 12, and 1 Corinthians 12 can all be described as ministries, but they cannot all be described as abilities.

5. The idea of ministry assignments is a common thread that weaves its way through Paul’s letters. The theme of special abilities is not an important theme in his writings.

6. In approximately 80 percent of Paul’s one hundred or so lists, he places a word or phrase that indicates the nature of the list in the immediate context. There are such indicators in all four of Paul’s lists. This is significant because indicators such as the words appointed, functions, and equipping instruct us that we must read these lists as ministries.

7. When Paul uses the words grace and given together, he’s discussing ministry assignments—either his own or those of others—in the immediate context. This combination appears in two of the three chapters that include ministry lists.

8. Paul talks in detail about his own ministry assignments and suggests that, just as he had received ministry, all believers have also received ministry assignments.

9. The spiritual-abilities view suggests that service should flow out of our strengths; Paul says that sometimes—though not always—we’re called to minister out of weakness. The weakness theme in Paul’s letters does not work with the idea of spiritual gifts as strengths.

10. Neither Paul nor any other New Testament author ever encourages people to try to discover their special abilities; nor is there any example of any New Testament character who embarked on such a quest.

You can read the whole interview here.

January 28, 2013

Principles for Writing Clearly and Coherently

At the The Gospel Coalition 2013 National Conference in Orlando I’ll be joining editor-friends Collin Hansen and Jennifer Lyell for a “focus gathering” panel on “How to Get Published” (April 9, 2013). We’ll discuss some of the nuts-and-bolts and try to answer some questions.

Frankly, a discussion of how to get published is not worth much if you cannot write well in the first place.

Here are two suggestions if you want to improve your writing:

1. Read this collection of quotes on “20 Great Writers on the Art of Revision,” and get the principle clearly fixed in your head.

2. Buy, read, and apply Joseph Williams’s Style: The Basics of Clarity and Grace. (There’s a guidebook/workbook as well.)

Here is a summary of the main points:

Ten Principles for Writing Clearly

1. Distinguish real grammatical rules from folklore.

2. Use subjects to name the characters in your story, avoiding abstractions.

3. Use verbs to name characters’ important actions, identifying actions and avoiding nominalizations.

4. Open your sentences with familiar units of information, utilizing introductory fragments and subordinate clauses at the beginnings of sentences.

5. Get to the main verb quickly:

Avoid long, complicated introductory phrases and clauses.

Avoid long abstract subjects.

Avoid interrupting the subject-verb connection.

6. Push new, complex units of information to the end of the sentence, providing transitions to get to them.

7. Begin sentences constituting a passage with consistent topic/subjects.

8. Be concise:

Cut meaningless and repeated words and obvious implications and clichés.

Put the meaning of phrases into one or two words.

Prefer affirmative sentences to negative ones.

9. Control Sprawl:

Don’t tack more than one subordinate clause onto another.

Extend a sentence with resumptive, summative, and free modifiers.

Extend a sentence with coordinate structures after verbs.

10. Above all, write to others as you would have others write to you.

Ten Principles for Writing Coherently

1. In your introduction, motivate readers to read carefully by stating a problem they should care about.

2. Make your point clearly, the solution to the problem, usually at the end of the introduction.

3. In that point, introduce the important concepts that you will develop in what follows.

4. Make it clear where each part/section begins and ends.

5. Make everything that follows relevant to your point.

6. Order parts in a way that makes clear and visible sense to your readers.

7. Open each part/section with its own short introductory segment.

8. Put the point of each part/section at the end of that opening segment.

9. Begin sentences constituting a passage with consistent topic/subjects.

10. Create cohesive old/new links between sentences.

If you find this kind of checklist helpful here’s another list, this one from Roy Peter Clark’s book, Writing Tools: 50 Essential Strategies for Every Writer:

I. Nuts and Bolts

1. Begin sentences with subjects and verbs.

Make meaning early, then let weaker elements branch to the right.

2. Order words for emphasis.

Place strong words at the beginning and at the end.

3. Activate your verbs.

Strong verbs create action, save words, and reveal the players.

4. Be passive-aggressive.

Use passive verbs to showcase the “victim” of action.

5. Watch those adverbs.

Use them to change the meaning of the verb.

6. Take it easy on the -ings.

Prefer the simple present or past.

7. Fear not the long sentence.

Take the reader on a journey of language and meaning.

8. Establish a pattern, then give it a twist.

Build parallel constructions, but cut across the grain.

9. Let punctuation control pace and space.

Learn the rules, but realize you have more options than you think.

10. Cut big, then small.

Prune the big limbs, then shake out the dead leaves.

II. Special Effects

11. Prefer the simple over the technical.

Use shorter words, sentences, and paragraphs at points of complexity.

12. Give key words their space.

Do not repeat a distinctive word unless you intend a specific effect.

13. Play with words, even in serious stories.

Choose words the average writer avoids but the average reader understands.

14. Get the name of the dog.

Dig for the concrete and specific, details that appeal to the senses.

15. Pay attention to names.

Interesting names attract the writer—and the reader.

16. Seek original images.

Reject cliches and first-level creativity.

17. Riff on the creative language of others.

Make word lists, free-associate, be surprised by language.

18. Set the pace with sentence length.

Vary sentences to influence the reader’s speed.

19. Vary the lengths of paragraphs.

Go short or long — or make a “turn”- to match your intent.

20. Choose the number of elements with a purpose in mind.

One, two, three, or four: Each sends a secret message to the reader.

21. Know when to back off and when to show off.

When the topic is most serious, understate; when least serious, exaggerate.

22. Climb up and down the ladder of abstraction.

Learn when to show, when to tell, and when to do both.

23. Tune your voice.

Read drafts aloud.

III. Blueprints

24. Work from a plan.

Index the big parts of your work.

25. Learn the difference between reports and stories.

Use one to render information, the other to render experience.

26. Use dialogue as a form of action.

Dialogue advances narrative; quotes delay it.

27. Reveal traits of character.

Show characteristics through scenes, details, and dialogue.

28. Put odd and interesting things next to each other.

Help the reader learn from contrast.

29. Foreshadow dramatic events or powerful conclusions.

Plant important clues early.

30. To generate suspense, use internal cliffhangers.

To propel readers, make them wait.

31. Build your work around a key question.

Good stories need an engine, a question the action answers for the reader.

32. Place gold coins along the path.

Reward the reader with high points, especially in the middle.

33. Repeat, repeat, repeat.

Purposeful repetition links the parts.

34. Write from different cinematic angles.

Turn your notebook into a “camera.”

35. Report and write for scenes.

Then align them in a meaningful sequence.

36. Mix narrative modes.

Combine story forms using the “broken line.”

37. In short pieces of writing, don’t waste a syllable.

Shape shorter works with wit and polish.

38. Prefer archetypes to stereotypes.

Use subtle symbols, not crashing cymbals.

39. Write toward an ending.

Help readers close the circle of meaning.

IV. Useful Habits

40. Draft a mission statement for your work.

To sharpen your learning, write about your writing.

41. Turn procrastination into rehearsal.

Plan and write it first in your head.

42. Do your homework well in advance.

Prepare for the expected — and unexpected.

43. Read for both form and content.

Examine the machinery beneath the text.

44. Save string.

For big projects, save scraps others would toss.

45. Break long projects into parts.

Then assemble the pieces into something whole.

46. Take interest in all crafts that support your work.

To do your best, help others do their best.

47. Recruit your own support group.

Create a corps of helpers for feedback.

48. Limit self-criticism in early drafts.

Turn it loose during revision.

49. Learn from your critics.

Tolerate even unreasonable criticism.

50. Own the tools of your craft.

Build a writing workbench to store your tools.

January 25, 2013

An Interview with Steve Wellum

Jeff Purswell recently interviewed Steve Wellum on Covenant Theology, hermeneutics, and biblical theology. You can listen to the audio here.

Jeff Purswell recently interviewed Steve Wellum on Covenant Theology, hermeneutics, and biblical theology. You can listen to the audio here.What follows is a helpful time-stamp outline they’ve provided.

[0:01] Dr. Wellum: husband, father, student, pastor, and professor

[4:18] A discussion on Dr. Wellum’s latest book, Kingdom Through Covenant

[6:50] Where does Dr. Wellum’s understanding of the covenants fit among Dispensationalism and Covenant Theology?

[12:46] What is the role of the Mosaic Law?

[15:46] What about the Sabbath command?

[19:08] Is the Mosaic Law normative for us?

[22:30] A discussion on hermeneutics

[26:22] Where are people most vulnerable to misinterpretation of Scripture?

[29:38] Wisdom for the young preacher/exegete

[32:16] Wisdom for the busy pastor who recognizes his need to grow in putting the whole of the Bible’s teaching together in his preaching

[35:42] Three prioritizes for a pastor’s ongoing study

[40:05] Every pastor should read these books…

[41:48] How has Dr. Wellum’s pastoral experience influenced his academic work?

January 24, 2013

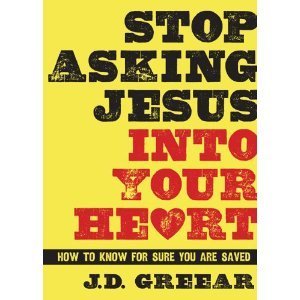

Stop Asking Jesus Into Your Heart!

Russell Moore writes the following about J. D. Greear’s new book, Stop Asking Jesus Into Your Heart: How to Know for Sure You Are Saved (B&H, 2013):

Russell Moore writes the following about J. D. Greear’s new book, Stop Asking Jesus Into Your Heart: How to Know for Sure You Are Saved (B&H, 2013):

I have to admit the title of this book made me uncomfortable. It sounded to me like a tract against the so-called “sinner’s prayer,” and I find it biblical to cry out “Lord have mercy on me, a sinner!” But as I read this book I found that is not what it is about at all. In this volume, J. D. Greear, one of the most dynamic and brilliant pastors in evangelical life today, addresses a common problem among Christians: the sense that we can never get assured enough that Jesus hears our sinners prayer and receives us, just as we are. This book throws the spotlight on Jesus as a welcoming, merciful Savior who joyously receives all who come to Him. This book could help free you, or someone you love, from the nagging fear that Jesus is trying to keep you out of His kingdom.”

A couple more commendations here:

“Salvation is a serious issue. Scripture commands us, on the one hand, to ‘work out our salvation with fear and trembling’ and, on the other, paints beautiful pictures of believers walking in great assurance. J.D. helps us see what conversion really is and what it is not. This book will be a help for those who wrestle with their position before God and a wake-up call for those with false confidence. I recommend it highly.”

—Matt Chandler, lead pastor, The Village Church, and president, Acts 29 Church Planting Network

“Warmly personal. Immensely helpful. Wonderfully practical. Thoroughly biblical. I wholeheartedly recommend this book to every Christian who longs to know, experience, and spread assurance of salvation in Christ.”

—David Platt, pastor, The Church at Brook Hills, Birmingham, AL, and author of New York Times bestselling Radical

January 23, 2013

A Message for Ordinary Pastors

Zack Eswine, author of Sensing Jesus: Life and Ministry as a Human Being, talks to pastors about significance even in ordinary things and in the midst of failure:

January 22, 2013

5 Things You Didn’t Know about “Jane Roe”

Today is the 40th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, the controversial Supreme Court ruling that progressives want to enshrine and conservatives want to overturn. Few rulings have been more consequential. According to Planned Parenthood’s Guttmacher Institute, 22% of all pregnancies now end in abortion, with 3 in 10 women terminating their pregnancy by the age of 45. There have been approximately 57 million legally induced abortions in the U.S. since 1973—nearly the current population of California and Texas combined.

Today is the 40th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, the controversial Supreme Court ruling that progressives want to enshrine and conservatives want to overturn. Few rulings have been more consequential. According to Planned Parenthood’s Guttmacher Institute, 22% of all pregnancies now end in abortion, with 3 in 10 women terminating their pregnancy by the age of 45. There have been approximately 57 million legally induced abortions in the U.S. since 1973—nearly the current population of California and Texas combined.

Yet a recent Pew study found that 4 in 10 “Millennials” don’t even know that Roe v. Wade has to do with abortion. And even fewer today know the true story of the woman who started it all, the pseudonymous plaintiff “Jane Roe.” Here are five things you may not know about her, culled from interviews and profiles along with her sworn congressional testimony and memoirs.

(1) The name “Jane Roe” was created over beer and pizza.

In 1969 Norma was 21 years old, divorced, and pregnant for the third time. (The first two children were placed for adoption.) After seeking an abortion but finding out it was illegal, and then driving to an illegal clinic only to find it closed, adoption attorney Henry McCluskey referred her to two young lawyers in Dallas, Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee. Weddington (who had traveled to Mexico a couple of years earlier to have an abortion) was seeking a class-action lawsuit against the state of Texas in order to legalize abortion. It was an unlikely party at the corner booth of Columbo’s pizza parlor in Dallas: two recent law-school grads in business suits sitting across the table from a rough and uneducated homeless woman. The lawyers needed a representative for all women seeking abortions—one who was young, poor, and white. They just didn’t want her to cross state lines to get a legal abortion, or the case would be considered moot and dismissed. Without money and five months pregnant, Norma was the ideal candidate. After downing several pitchers of beer, they agreed on using the pseudonym “Jane Roe.” (“Wade” referred to Henry B. Wade, the attorney general of Dallas.)

(2) Jane Roe didn’t know the meaning of “abortion.”

Weddington and Coffee told Norma that abortion just dealt with a piece of tissue, and that it was like passing a period rather than the termination of a distinct, living, and whole human organism. Abortion was a taboo topic in 1970, and Norma had dropped out of school at the age of 14. She knew that John Wayne movies talked about “aborting the mission,” so she thought it meant to “go back”—as in, going back to not being pregnant. She honestly believed “abortion” meant a child was prevented from coming into existence.

(3) Jane Roe never appeared in court.

Her lawyers drafted a one-page legal affidavit, which she signed but did not read. (Even today, she has not read it.) This was only the second time she would meet with her lawyers—and it turned out to be the last. She would not be called to testify and attended none of the trial. She found out about the Supreme Court ruling from the newspaper on January 23, 1973, just like the rest of the nation. Few on that day understood the implications of Justice Blackmun’s instruction that Roe v. Wade was to be read in conjunction with its companion case Doe v. Bolton, which effectively made abortion legal at any stage of pregnancy for any reason. As a result, the United States (with Canada) became the only Western country offering no legal protection for the unborn at any stage of the pregnancy.

(4) Jane Roe never had an abortion.

Norma had already given birth and placed the baby for adoption before the three-judge Texas panel ruled against her in May of 1970, long before the Supreme Court decision in January of 1973. She was in a committed lesbian relationship and would not become pregnant again. Abortion continued to be a part of her life, however. She went on to work in abortion clinics, holding the hands of women and offering reassurance as they terminated their pregnancies, and making appearances on the Roe anniversaries.

(5) Jane Roe became pro-life.

In 1995, while working at the clinic, Norma became haunted by the sight and sound of empty playgrounds in her neighborhood. Once teeming with kids, they now seemed deserted. And she began to see it was the result of what she once called “my law.” But the decisive change happened when she met Emily Mackey, a seven-year-old girl whose parents were protesting at the clinic where “Miss Norma” worked. Emily, who had almost been aborted herself, befriended Norma, showing genuine interest and love, giving her hugs and inviting her to church. Through the influence this young girl’s combination of truth and grace, along with those who shared the gospel of Jesus with her, Norma not only became convinced of the pro-life position but also converted to Christianity.

* * *

Norma McCorvey now says that “Jane Roe has been laid to rest.” Both sides in America’s most contentious debate have claimed her at one point, and both have had reason to be disappointed. But for evangelicals—the demographic most committed to overturning Roe—the case for protecting the smallest and most defenseless members of the human race does not rest with the testimony of a single individual. It does not even rest on biblical revelation; moral philosophers have pointed out that the differences between a fetus in utero and an infant outside the womb—size, location, degree of dependency, and level of development—are morally irrelevant when determining a person’s right to life.

On this fortieth anniversary of Roe v. Wade, evangelicals would do well to remember that we must not only labor to protect the unborn, but to continue reaching out with assistance and love and the good news of grace to the Norma McCorveys of the world—broken women who feel they have no other place to turn.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers