Justin Taylor's Blog, page 159

May 8, 2013

The Other Lord’s Prayer

Mike Reeves looks at John 17, where we get to eavesdrop on the Trinity praying for us:

Spurgeon on Why You Should Read Wesley on the Christian Life

Calvinistic Baptist preacher Charles Spurgeon grew tired of the John-Wesley haters of his day:

Calvinistic Baptist preacher Charles Spurgeon grew tired of the John-Wesley haters of his day:

To ultra-Calvinists his name is as abhorrent as the name of the Pope to a Protestant: you have only to speak of Wesley, and every imaginable evil is conjured up before their eyes, and no doom is thought to be sufficiently horrible for such an arch-heretic as he was. I verily believe that there are some who would be glad to rake up his bones from the tomb and burn them, as they did the bones of Wycliffe of old—men who go so high in doctrine, and withal add so much bitterness and uncharitableness to it, that they cannot imagine that a man can fear God at all unless he believes precisely as they do.

But he also had little patience for the Wesley fanboys:

Unless you can give him constant adulation, unless you are prepared to affirm that he had no faults, and that he had every virtue, even impossible virtues, you cannot possibly satisfy his admirers.

Spurgeon had a different posture toward Wesley: critical appreciation.

I am afraid that most of us are half asleep, and those that are a little awake have not begun to feel. It will be time for us to find fault with John and Charles Wesley, not when we discover their mistakes, but when we have cured our own. When we shall have more piety than they, more fire, more grace, more burning love, more intense unselfishness, then, and not till then, may we begin to find fault and criticize.

I think he would have liked and recommended Fred Sanders’s forthcoming Wesley on the Christian Life. We can learn from the truth that he saw and the mistakes that he made. I know I profited from the book, and I think the same will be true for many readers.

May 7, 2013

10 Reasons Why Hymnals Have a Future

John D. Witvliet outlines ten reasons:

John D. Witvliet outlines ten reasons:

Hymnals are especially well suited to good group singing of many kinds of songs (though not all).

Hymnals are portable.

Hymnals are splendid for home piano or keyboard devotional playing.

Hymnals are an efficient one-stop worship planning resource.

Hymnals make it relatively easy to stumble on and fall in love with good music you never thought you would like.

Well-designed hymnals offer a vision of a balanced thematic diet.

Hymnals help connect songs with elements of worship.

Hymnals give people access to a “cultural memory bank” that many desperately want.

Hymnals can be appealing to seekers.

A hymnal can be a surprisingly effective catechism for both brand-new and lifelong Christians.

You can read the whole thing here to see an explanation of each point.

He concludes:

In summary, hymnals are a good resource, not the only good resource. And they may not be even the best single resource for every one of these functions. But for overall value, it’s pretty hard to beat a single book that does so many things at once:

provides a comprehensive reference resource for finding songs and one technological mode of presenting songs;

functions as a musical collection and a worship book, with prayers and liturgies for congregational use;

presents a single-volume snap-shot of the diversity of the church throughout time and space, a kind of working experiment in the “catholicity” or “universality” of the church; and

acts as a single source for strengthening devotional, pastoral care, educational, and liturgical ministries, making it possible to integrate these dimensions of the Christian life.And hymnals like Lift Up Your Hearts do all this while providing almost one thousand songs for around twenty dollars, or a mere two cents per song.

HT: Bobby Giles

How a Writer of Words Recognized the Author of the Word

Novelist Larry Woiwode writes in Words for Readers and Writers:

The pages I’ve composed as a writer, millions of finished sentences, attempt to embody through words aspects of the Word in people and their actions, or to amplify its traditions to include human beings attempting to live out lives of belief or unbelief in the world we all experience daily.

In Acts you will find,

For me, a writer aware of how much more complex each book becomes with each sentence added, it was the clarity of the patterns and structure in Scripture and their ability to intermesh with one another through as many levels as I could imagine that convinced me that the Bible couldn’t be the creation of a man or any number of men, and was certainly not the product of separate men divided by centuries, but was of another world: supernatural.

I was forced to admit under no pressure but the pressure of the text itself that it could be only what it claimed it was, the Word of God.

h

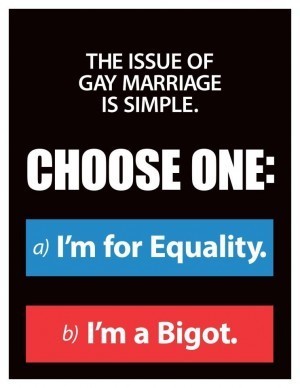

The Gay Marriage Campaign and the Despotism of Conformism

Journalist Brendan O’Neill, who is an atheist (in terms of religion) and a libertarian (in terms of politics), recently wrote about “the peculiar non-judgmental tyranny of the gay-marriage campaign, which judges harshly those who dare to judge how people live.” He writes, “Opponents of gay marriage are now treated by the press in the same way queer-rights agitators were in the past: as strange, depraved creatures, whose repenting and surrender to mainstream values we await with bated breath.”

Journalist Brendan O’Neill, who is an atheist (in terms of religion) and a libertarian (in terms of politics), recently wrote about “the peculiar non-judgmental tyranny of the gay-marriage campaign, which judges harshly those who dare to judge how people live.” He writes, “Opponents of gay marriage are now treated by the press in the same way queer-rights agitators were in the past: as strange, depraved creatures, whose repenting and surrender to mainstream values we await with bated breath.”

He thinks this is more “conformism” than “consensus”:

I don’t think we can even call this a ‘consensus’, since that would imply the voluntaristic coming together of different elements in concord. It’s better described as conformism, the slow but sure sacrifice of critical thinking and dissenting opinion under pressure to accept that which has been defined as a good by the upper echelons of society: gay marriage. Indeed, the gay-marriage campaign provides a case study in conformism, a searing insight into how soft authoritarianism and peer pressure are applied in the modern age to sideline and eventually do away with any view considered overly judgmental, outdated, discriminatory, ‘phobic’, or otherwise beyond the pale.

Later in the piece he writes:

In truth, the extraordinary rise of gay marriage speaks, not to a new spirit of liberty or equality on a par with the civil-rights movements of the 1960s, but rather to the political and moral conformism of our age; to the weirdly judgmental non-judgmentalism of our PC times; to the way in which, in an uncritical era such as ours, ideas can become dogma with alarming ease and speed; to the difficulty of speaking one’s mind or sticking with one’s beliefs at a time when doubt and disagreement are pathologised. Gay marriage brilliantly shows how political narratives are forged these days, and how people are made to accept them. This is a campaign that is elitist in nature, in the sense that, in direct contrast to those civil-rights agitators of old, it came from the top of society down; and it is a campaign which is extremely unforgiving of dissent or disagreement, implicitly, softly demanding acquiescence to its agenda.

And here’s his conclusion:

The conformism around gay marriage cannot be put entirely down to handfuls of campaigners, of course, and certainly not to any conscious attempt on their part to enforce political and moral obedience. The fragility of society’s attachment to traditional marriage itself, to the virtue of commitment, has also been key to the formulation of the gay-marriage consensus. Indeed, it is the rubble upon which the gay-marriage edifice is built. That is, if lawyers, politicians and our other assorted ‘betters’ have successfully kicked down the door of traditional marriage, it’s because the door was already hanging off its hinges, following years of cultural neglect. It is society’s reluctance to defend traditional views of commitment, and its relativistic refusal more broadly to discriminate between different lifestyle choices, that has fuelled the peculiar non-judgmental tyranny of the gay-marriage campaign, which judges harshly those who dare to judge how people live. Through a combination of the weakness of belief in traditional marriage and the insidiousness of the campaign for gay marriage, we have ended up with something that reflects brilliantly John Stuart Mill’s description of how critical thinking can cave into the despotism of conformism, so that ‘peculiarity of taste, eccentricity of conduct, are shunned equally with crimes, until by dint of not following their own nature, these [followers of conformism] have no nature to follow’

You can read the whole thing here.

HT: Mike Reeves

May 6, 2013

Spurgeon on Worry and Prayer

A farmer stood in his fields and said,

I do not know what will happen to us all.

The wheat will be destroyed if this rain keeps on.

We shall not have any harvest at all unless we have some fine weather.

He walked up and down, wringing his hands, fretting and making his whole household uncomfortable.

And he did not produce one single gleam of sunlight by all his worrying—he could not puff any of the clouds away with all his petulant speech, nor could he stop a drop of rain with all his murmurings.

What is the good of it, then, to keep gnawing at your own heart, when you can get nothing by it? . . . .

In the same sermon Spurgeon offers another illustration:

I have often used the illustration (I do not know a better) of taking a telescope, breathing on it with the hot breath of our anxiety, putting it to our eye and then saying that we cannot see anything but clouds!

Of course we cannot, and we never shall while we breathe upon it.

The Foreignness of Biblical Metaphors

Years ago Raymond Van Leeuwen, professor of biblical studies Eastern College, wrote a helpful piece on Bible translation in Christianity Today, explaining why it is important to retain biblical metaphors as much as possible:

Metaphors grab us and work on us and in us. . . . Biblical metaphors drop into our hearts like a seed in soil and make us think, precisely because they are not obvious at first. . . . [I]t is the foreignness of metaphors that is their virtue. Metaphors make us stop and think, Now what does that mean? It is not clear to me that replacing metaphors with abstractions makes it easier for readers. . . . Metaphors are multifaceted and function to invoke active thought on the part of the receiver. Receivers must think and feel their way through a metaphor, and it is this very process that gives the metaphor its power to take hold of receivers as they take hold of it. . . . [I]f the original is mysterious, ambiguous, complex, rich in metaphorical suggestiveness, or just foreign and shocking to our sensibilities, so be it.

Alan Jacobs, in a piece on Bible translation for First Things, explains that we have to understand the difference between a metaphor and an idiom, applying this to the image that David is said to be “sleeping with his fathers” (1 Kings 2:10).

It is a distinction both simple and vital. It is highly unlikely that a Jew of David’s time, or at any time in Israel’s history, would have found a family member’s dead body and run to tell everyone that grandpa was now sleeping with his fathers. Hebrew has words to express quite directly that someone has died; the chronicler of Kings chooses here to eschew them in favor of a particularly hieratic and formal way of describing the death of David. When (in 2 Samuel 1) a man comes from the camp of Israel’s army to report to David, he says simply that Saul (along with his son Jonathan) has died. The deaths of Saul and Jonathan are given no cultural or political meaning, because by the time this history was written the people of Israel no longer identified Saul as having special importance for their national identity.

David, by contrast, is for the Israelites their first true King, the head of a proper dynastic line; therefore he does not merely die, he “sleeps with his fathers” in Jerusalem, the “city of David.” The phrase is not an idiom—a common phrase lacking an evident literal meaning—instead, it is a carefully chosen image of David’s place in the culture of Israel.

For more thinking on meaning and metaphors in general, here’s a recent conversation with Tony Reinke and Doug Wilson on the subject.

The Curious Incident of Modern Evangelicalism

Francis Chan and David Platt, in the foreword to a redesignd edition of John Piper’s A Hunger for God:

As we look out at the church today, there is so much that encourages us and fills us with gratitude. There is renewed zeal among God’s people for the spread of God’s glory across the earth. Like never before we hear brothers and sisters in different circles and different streams of contemporary Christianity talking about the gospel and mission, about transforming cities and reaching unreached people groups. These conversations are essential, and we hope they will continue with even greater intensity and intentionality in the days ahead.

But sometimes what we are not hearing can be as illuminating as what we do hear. It reminds us of an exchange in an old Sherlock Holmes mystery, where Holmes refers to “the curious incident of the dog in the night-time” during a robbery. A fellow detective, confused at Holmes’s comment, responds that “the dog did nothing in the nighttime” — to which Holmes responds: “That was the curious incident.” Despite the proliferation of Christian publishing and Christian conferences, J. I. Packer’s observation of our own curious incident still rings true:

When Christians meet, they talk to each other about their Christian work and Christian interests, their Christian acquaintances, the state of the churches, and the problems of theology — but rarely of their daily experience of God.

Modern Christian books and magazines contain much about Christian doctrine, Christian standards, problems of Christian conduct, techniques of Christian service — but little about the inner realities of fellowship with God.

Our sermons contain much sound doctrine — but little relating to the converse between the soul and the Saviour.

We do not spend much time, alone or together, in dwelling on the wonder of the fact that God and sinners have communion at all; no, we just take that for granted, and give our minds to other matters.

Thus we make it plain that communion with God is a small thing to us.

Think about it. Where are the passionate conversations today about communing with God through fasting and prayer? We seem to find it easier to talk much of plans and principles for proclaiming the gospel and planting churches, and to talk little of the power of God that is necessary for this gospel to be proclaimed and the church to be planted.

You can read the whole foreword here, and get the book here.

May 3, 2013

What Is the Difference between Affections and Emotions?

As Gerald McDermott explains, Jonathan Edwards saw affections as “strong inclinations of the soul that are manifested in thinking, feeling and acting” (Seeing God: Jonathan Edwards and Spiritual Discernment, p. 31).

A common confusion is to equate “affections” with “emotions.” But there are several differences, as summarized in this chart from McDermott (p. 40):

Affections

Emotions

Long-lasting

Fleeting

Deep

Superficial

Consistent with beliefs

Sometimes overpowering

Always result in action

Often fail to produce action

Involve mind, will, feelings

Feelings (often) disconnected from the mind and will

He explains why affections are different than emotions:

Emotions (feelings) are often involved in affections, but the affections are not defined by emotional feeling. Some emotions are disconnected from our strongest inclinations.

For instance, a student who goes off to college for the first time may feel doubtful and fearful. She will probably miss her friends and family at home. A part of her may even try to convince her to go back home. But she will discount these fleeting emotions as simply that—feelings that are not produced by her basic conviction that now it is time to start a new chapter in life.

The affections are something like that girl’s basic conviction that she should go to college, despite fleeting emotions that would keep her at home. They are strong inclination that may at times conflict with more fleeting and superficial emotions. (pp. 32-33)

Here is how Sam Storms explains the difference in Signs of the Spirit: An Interpretation of Jonathan Edwards’ “Religious Affections:

Certainly there is what may rightly be called an emotional dimension to affections. Affections, after all, are sensible and intense longings or aversions of the will. Perhaps it would be best to say that whereas affections are not less than emotions, they are surely more.

Emotions can often be no more than physiologically heightened states of either euphoria or fear that are unrelated to what the mind perceives as true.

Affections, on the other hand, are always the fruit or effect of what the mind understands and knows. The will or inclination is moved either toward or away from something that is perceived by the mind.

An emotion or mere feeling, on the other hand, can rise or fall independently of and unrelated to anything in the mind.

One can experience an emotion or feeling without it properly being an affection, but one can rarely if ever experience an affection without it being emotional and involving intense feelings that awaken and move and stir the body. (p. 45)

May 2, 2013

Martin Bashir Explains the Gospel to Bill O’Reilly

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers