Justin Taylor's Blog, page 154

June 5, 2013

Ira Glass on How the Media Portrays Christians

Interesting thoughts from Jewish atheist Ira Glass, host of “This American Life”:

Via Lore Ferguson and Luma Simms

So Why Are Performance-Enhancing Drugs Wrong?

ESPN’s Outside the Lines reports that “Major League Baseball will seek to suspend about 20 players connected to the Miami-area clinic at the heart of an ongoing performance-enhancing drug scandal, including Alex Rodriguez and Ryan Braun. . . . If the suspensions are upheld, the performance-enhancing drug scandal would be the largest in American sports history.”

ESPN’s Outside the Lines reports that “Major League Baseball will seek to suspend about 20 players connected to the Miami-area clinic at the heart of an ongoing performance-enhancing drug scandal, including Alex Rodriguez and Ryan Braun. . . . If the suspensions are upheld, the performance-enhancing drug scandal would be the largest in American sports history.”

It’s worth thinking through the ethics of performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs). If everyone is doing it, is it still wrong? Would they be okay if they were regulated and administered safely? Do our answers say say something about the nature of the game itself? Do they say something about our view of human nature?

Justin Barnard—director of the Carl F.H. Henry Institute for Intellectual Discipleship and associate professor of philosophy at Union University—has done some helpful work on this and related questions. Here is an excerpt:

Thole point of using performance-enhancing drugs is to hit the ball harder and hence, farther. But while the ability to hit the ball well (e.g., hard) is a good, it is only one good, among many, in the game of baseball considered as a whole. And among those for whom it is morally bothersome, this is precisely what bothers fans when heroes are exposed for having violated the purity of the game.

Specifically, the use of performance-enhancing drugs in baseball violates the integral relationship that exists among all of the game’s goods considered as a whole by virtue of employing means (i.e., performance-enhancing drugs) which, by their very nature, treat a single good as though it were an exclusive end in itself (i.e., the good of hitting the ball a very long distance or even more basically, the good of raw athletic power or strength). By their very nature, performance-enhancing drugs work so as to maximize a single good (e.g., muscles that are bigger, faster, stronger, etc.). Moreover, the use of such drugs in baseball (or in any other sport for that matter) implicitly treats the single good at which the drug aims as though it were the most important or only good of the game considered as a whole. That this is false about home-run-hitting is illustrated by the robotic baseball thought experiment. If merely hitting the ball (very far!) were the most important or only good of the game of baseball considered as a whole, why not get rid of the players and replace them with machines? After all, we already have the technology to create machines capable of hitting baseballs farther than most steroid-enhanced players alive!

Of course, the thought experiment helps us to realize that home-run-hitting, exciting and important as it is, is merely one good among many in the game of baseball considered as a whole. Activities like the use of performance-enhancing drugs trouble us morally—not merely because of the conventions of the game—but more significantly because they violate the overarching goodness of the unity of the game’s goods, considered as a whole.

June 4, 2013

A World without God

In a universe of blind physical forces and genetic replication, some people are going to get hurt, other people are going to get lucky, and you won’t find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice. The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference.

—Richard Dawkins, River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life (Basic Books, 1995), 95.

Such, in outline, but even more purposeless, more void of meaning, is the world which Science presents for our belief. Amid such a world, if anywhere, our ideals henceforward must find a home.

That Man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving;

that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms;

that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave;

that all the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system,

and that the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins—

all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand.

Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built.

—Bertrand Russell, “A Free Man’s Worship” (1903); emphasis added.

The Bible Is Not Your Supermarket

D. A. Carson’s excellent book How Long, O Lord? Reflections on Suffering and Evil is, by his own admission, not the best book to give someone in the midst of grief and suffering. He explains his view that this book is “preventative medicine.” “Quite frankly,” he writes, “this little book . . . may not be of assistance to those whose despair is so bleak that they cannot bring themselves to read, think, and pray. But I shall be satisfied if it helps some Christians establish patterns and habits of thought that are so strong that when the hardest questions batter the soul there is less wavering and more faith, joy, and hope” (p. 10).

At the end of chapter 6, he returns to the question of a young woman who wanted to know how she should think of her father, who, as far as she knew, was now in hell.

There were, of course, and are, many important things to say.

I could say that none of us knows for certain what transpires between any person and God Almighty before that person is ushered into eternity.

I could say that the final proof of the love and goodness of God is the cross.

I could say that we know far too little of the new heaven and the new earth to have any idea what consciousness we shall there have of those who have chosen to live and die independently of God.

I could add that there are times when, in the confusion, it sometimes helps to think of all that we know of the character of God and ask, with Abraham, the rhetorical question, “Will not the Judge of all the earth do right?” (Gen. 18:25).

All this I could say, and more.

But it will not do to opt for a sub-biblical system, a selectively biblical system.

Shall we opt for absolute universalism? Then what do we do with the countless texts that foreclose on this speculation? Does God treat those who trust his Son and those who disobey the Son the same way, even though his Word insists, “Whoever believes in the Son has eternal life, but whoever rejects the Son will not see life, for God’s wrath remains on him” (John 3:36)?

Shall we assume that truth and revelation are not the discriminating factors, but human sincerity? What purpose, then, the cross? And what value?

However hard some things are to understand, it is never helpful to start picking and choosing biblical truths we find congenial, as if the Bible is an open-shelved supermarket where we are at perfect liberty to choose only the chocolate bars.

For the Christian, it is God’s Word, and it is not negotiable. What answers we find may not be exhaustive, but they give us the God who is there, and who gives us some measure of comfort and assurance.

The alternative is a god we manufacture, and who provides no comfort at all. Whatever comfort we feel is self-delusion, and it will be stripped away at the end when we give an account to the God who has spoken to us, not only in Scripture, but supremely in his Son Jesus Christ.

—D. A. Carson, How Long, O Lord?: Reflections on Suffering and Evil (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1990), 105-106.

Remind God about His Son

In a sermon, Spurgeon quotes an unnamed pastor who spoke on why God hears our prayers:

Remember, the Lord will not hear you, because of the arithmetic of your prayers; he does not count their numbers.

He will not hear you because of the rhetoric of your prayers; he does not care for the eloquent language in which they are conveyed.

He will not listen to you because of the geometry of your prayers; he does not compute them by their length, or by their width.

He will not regard you because of the music of your prayers; he does not care for sweet voices, nor for harmonious periods.

Neither will he look at you because of the logic of your prayers; because they are well arranged and compartmentalized.

But he will hear you, and he will measure the amount of the blessing he will give you, according to the divinity of your prayers. If you can plead the person of Christ, and if the Holy Spirit inspires you with zeal and earnestness, the blessings which you shall ask, will surely come to you.

In another sermon, he picks up on this theme:

You may ring that bell as long as you ever will—the Father will never weary of it.

Tell Him what His Son has done.

Remind Him of Gethsemane.

Bring up before the Father’s mind the Cross of Calvary.

Tell Him of His promise to His Son—that He shall see His seed and have a full reward.

You cannot by any possibility displease God by dwelling upon this topic. Hold Him with it, yes, hold Him with the resolution of a Jacob, and say, “I will not let You go until You bless me, for I plead the name and merit of Your only begotten Son.”

June 3, 2013

Wolterstorff on Christian Scholarship and the Love of Understanding

Anyone encouraged in the life of the mind—especially those who are students, teachers, scholars, or aspire to scholarship—would do well to spend an hour listening to this lecture by Nicholas Wolterstorff: “Fides Quaerens Intellectum,” delivered at a conference for the Biola University Center for Christian Thought (May 18-19, 2012):

The first hour is Professor Wolterstorff’s lecture, followed by a half hour of interaction with the audience. This is rich material drawn from a lifetime of scholarship in the service of love. One doesn’t need to agree with all of it to profit from it.

Wolterstorff defines “the project of being a Christian scholar” as “the project of thinking with a Christian mind and speaking with an appropriate Christian voice within your chosen discipline and within the academy more generally.”

You can see written versions of portions of the remarks here and there.

Here is his advice to aspiring Christian scholars:

First, be patient. The Christian scholar may feel in his bones that some part of his discipline rubs against the grain of his Christian conviction, but for years, and even decades, he may not be able to identify precisely the point of conflict; or, if he has identified it, he may not know for years or decades how to work out an alternative. Once he does spy the outlines of an alternative, the Christian scholar has to look for the points on which, as it were, he can pry, those points where he can get his partners in the discipline to say, “Hmm, you have a point there; I’m going to have to go home and think about that.” He doesn’t just preach. He engages in a dialogue—or tries to do so. And that presupposes, once again, that he has found a voice.

Second, to arrive at this point, the Christian scholar will have to be immersed in the discipline and be really good at it. Grenades lobbed by those who don’t know what they are talking about will have no effect. Only those who are learned in the discipline can see the fundamental issues.

Third, to be able to think with a Christian mind about the issues in your discipline, you have to have a Christian mind.

As I see it, three things are necessary for the acquisition of such a mind.

First, you have to be well acquainted with Scripture—not little tidbits, not golden nuggets, but the pattern of biblical thought. Let me add here: beware of the currently popular fad of reducing acquaintance with scripture to worldview summaries.

Second, you need some knowledge of the Christian theological tradition.

And third, you have to become acquainted with the riches of the Christian intellectual tradition generally, especially those parts of it that pertain to your own field. Too often American Christians operate on the assumption that we in our day are beginning anew, or on the assumption that nothing important has preceded us. You and I are the inheritors of an enormously rich tradition of Christian reflection on politics, on economics, on psychology, an enormously rich tradition of art, of music, of poetry, of architecture—on and on it goes. We impoverish ourselves if we ignore this. Part of our responsibility as Christian scholars is to keep those traditions alive.

Fourth, Christian learning needs the nourishment of communal worship. Otherwise it becomes dry and brittle, easily susceptible to skepticism.

Glimpses of Grace: Treasuring the Gospel in Your Home

Gloria Furman explains the vision of her excellent new book, Glimpses of Grace: Treasuring the Gospel in Your Home

You can preview the book below, or download an excerpt here.

There Are Worse Things Than Dying

I do not know how many times I have sung the words, “O let me never, never / Outlive my love for Thee,” but I mean them.

I would rather die than end up unfaithful to my wife; I would rather die than deny by a profligate life what I have taught in my books; I would rather die than deny or disown the gospel.

God knows there are many things in my past of which I am deeply ashamed; I would not want such shame to multiple and bring dishonor to Christ in years to come.

There are worse things than dying.

—D. A. Carson, How Long, O Lord? Reflections on Suffering and Evil (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1990), 120.

May 31, 2013

Louis Berkhof’s Systematic Theology: Now Free as an eBook

Thanks to BiblicalTraining.org, Berkhof’s classic theology text is now freely (and legally) available here.

Thanks to BiblicalTraining.org, Berkhof’s classic theology text is now freely (and legally) available here.

Berkhof (1873-1957) was born in the Netherlands, and his family moved to Grand Rapids when he was 9.

After graduating from Calvin Theological Seminary and Princeton Theological Seminary, he returned to Calvin and joined the faculty. For the first two decades he taught biblical studies, and then for almost two decades after that he taught systematic theology. He also became president of the seminary in 1931 and continued so until his retirement in 1944.

His Systematic Theology was published in 1932 and revised in 1938.

Wayne Grudem has said Berkhof’s Systematic Theology is “a great treasure-house of information and analysis . . . probably the most useful . . . systematic theology available from any theological perspective.” Richard Muller calls it “the best modern English-language introduction to doctrinal theology of the Reformed tradition.”

It tends a bit toward proof-texting‚ which is not to say that Scripture is regularly misused but that he does not generally show his exegetical work. Further, the book is not very original or creative. In many ways, it is an English summary of Bavinck and a compendium of mainstream Reformed theology.

But having read every word of this influential work, I have no hesitation in warmly commending it as one of the most useful ways to get an excellent summary of virtually all areas of systematic theology.

May 30, 2013

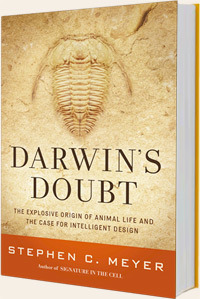

Darwin’s Doubt: An Interview with Stephen C. Meyer

Dr. Stephen C. Meyer, author of Signature in the Cell: DNA and the Evidence for Intelligent Design and director of the Discovery Institute’s Center for Science and Culture, has a new book being published June 18 by HarperOne: Darwin’s Doubt: The Explosive Origin of Animal Life and the Case for Intelligent Design.

Dr. Stephen C. Meyer, author of Signature in the Cell: DNA and the Evidence for Intelligent Design and director of the Discovery Institute’s Center for Science and Culture, has a new book being published June 18 by HarperOne: Darwin’s Doubt: The Explosive Origin of Animal Life and the Case for Intelligent Design.

(For the best discount and free shipping, you can pre-order the book here, and they’ll also send you four free eBooks on intelligent design.)

Dr. Meyer argues that the mysterious features of the Cambrian explosion are better explained by intelligent design than purely undirected evolutionary processes. He was kind enough to answer a few questions.

What is the “Cambrian Explosion”?

The Cambrian explosion is an important event in the history of life where nearly all of the major animal body plans appear abruptly in the fossil record without any apparent evolutionary precursors.

Why is that significant?

What this means, in essence, is that virtually all of the major animal groups (called “phyla”)—vertebrates like fish, to arthropods (e.g., trilobites and shrimplike creatures), to various types of worms (e.g., earthworm-like annelid worms), to mollusks (e.g., shellfish), and many other types of animals—appear in a geological “blink of an eye,” without any direct ancestors in the fossil record. Even Richard Dawkins has observed that the Cambrian animals looked as if “they were just planted there without any evolutionary history.”

Do you believe it was a real event?

Yes, we take the Cambrian explosion to have been a real event. And we aren’t alone in taking that view. Most leading evolutionary paleontologists who are top authorities on the Cambrian period—people like Douglas Erwin, James Valentine, and Simon Conway Morris—agree that the evidence shows the Cambrian explosion was a real event, and is not merely an artifact of the fossil record.

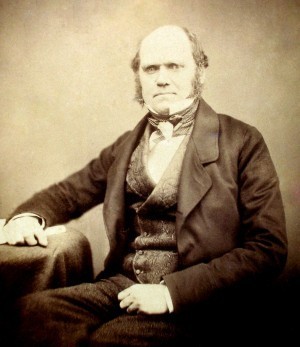

Did Darwin know about the Cambrian explosion? Did he see problems with it?

Did Darwin know about the Cambrian explosion? Did he see problems with it?

Darwin himself knew that the abrupt appearance of animals in the ancient fossil record posed a problem for his theory. In his time, it was called the Silurian period, but later it was renamed the Cambrian.

Darwin knew that his theory of evolution by natural selection worked gradually, and required that structures and organs be built by “numerous, successive, slight modifications.”

But the Cambrian explosion contradicted that pattern, since it showed diverse and complex animal body plans appearing abruptly, without any fossil record of their evolution.

Darwin confessed that this was not something his theory could explain. He acknowledged that doubt in Origin of Species, and said it was a “valid argument against the views here entertained.”

Have the last century of fossil discoveries resolved or aggravated Darwin’s doubt?

Fossil discoveries since Darwin’s time have only made the Cambrian explosion problem worse for his theory.

Darwin believed that the fossil record was woefully incomplete, and he predicted that the problem of abrupt appearance of animals in the Cambrian would be alleviated by future discoveries.

But the opposite happened. Scientists have combed the Precambrian strata for the alleged precursors to the Cambrian animals, and they haven’t found the direct evolutionary ancestors that Darwinian theory predicts. Instead, they have made new discoveries which confirmed that the Cambrian explosion was real event—and a worldwide one—and that the animal phyla really did appear abruptly.

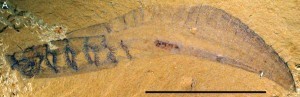

The first major Cambrian-era fossil discovery after Darwin’s time took place over a hundred years ago now, in 1909, when Charles Doolittle Walcott (then the head of the Smithsonian Institution) discovered the Burgess Shale Cambrian deposit in the Canadian Rockies. This deposit showed many diverse soft and hard-bodied organisms which were preserved in exquisite detail. They all appeared in the Cambrian, with no clear evolutionary ancestors.

The first major Cambrian-era fossil discovery after Darwin’s time took place over a hundred years ago now, in 1909, when Charles Doolittle Walcott (then the head of the Smithsonian Institution) discovered the Burgess Shale Cambrian deposit in the Canadian Rockies. This deposit showed many diverse soft and hard-bodied organisms which were preserved in exquisite detail. They all appeared in the Cambrian, with no clear evolutionary ancestors.

The question remained, however, whether the Burgess Shale Cambrian animals were a lucky isolated event, or evidence of a worldwide pattern. Over the next decades, additional discoveries of Cambrian animals were made in other parts of the world, including Russia, Greenland, and Australia.

But the most spectacular find of all took place in 1984, with the discovery of Cambrian fossils in Chengjiang, China. This deposit confirmed that the Cambrian explosion was a worldwide event, with many of the same creatures found in Canada being present in beautiful detail.

But the most spectacular find of all took place in 1984, with the discovery of Cambrian fossils in Chengjiang, China. This deposit confirmed that the Cambrian explosion was a worldwide event, with many of the same creatures found in Canada being present in beautiful detail.

So as more and more fossils have been discovered, we’ve found the same pattern over and over around the world: diverse types of animals appear abruptly in the Cambrian, without clear evolutionary precursors. This has accentuated the “dilemma” that Darwin faced.

How do you respond to the argument that humans can trace their evolutionary ancestry to the Cambrian fish since both share backbones and dorsal nerve cords?

How do you respond to the argument that humans can trace their evolutionary ancestry to the Cambrian fish since both share backbones and dorsal nerve cords?

Sure, humans and fish both share backbones and nerve codes. That’s no surprise to anyone. In fact, humans also share genes with bananas and bacteria. That organisms share genes or structural parts does not necessarily reflect common ancestry, because it could indicate that they were built upon a common body plan. After all, it’s a good design principle to re-use parts that work in different designs—this is exactly why mechanical engineers put wheels on both cars and airplanes, or why technology designers put keyboards on both computers and cell phones. That different organisms share some of the same parts could easily reflect common design rather than common descent.

In fact, when evolutionary biologists have tried to construct evolutionary trees (called “phylogenetic trees”) to show how the animal phyla are related, they have encountered great difficulties. An evolutionary tree based on one gene or body part, will sharply conflict with an evolutionary tree based upon another gene or body part. A paper just published in the journal Nature last week acknowledged that the genetic data has caused a lot of problems for those trying to construct a “tree of life.” One of the study’s co-authors, Antonis Rokas of Vanderbilt University, stated: “It has become common for top-notch studies to report genealogies that strongly contradict each other in where certain organisms sprang from, such as the place of sponges on the animal tree or of snails on the tree of mollusks.”

To see how Dr. Meyer connects all of this to intelligent design, check out the book: Darwin’s Doubt.

You can also watch below a trailer for an earlier documentary that began to explore these issues:

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers