Justin Taylor's Blog, page 136

October 2, 2013

15 Biography Recommendations: D.G. Hart, Sean Lucas, Kevin DeYoung

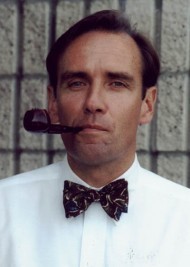

D. G. Hart is visiting professor of history at Hillsdale College and the author of the standard biography of J. Gresham Machen, and most recently, a history of Calvinism.

D. G. Hart is visiting professor of history at Hillsdale College and the author of the standard biography of J. Gresham Machen, and most recently, a history of Calvinism.

Here are five biographies he recommends:

1. Roland Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (1950).

A colorful treatment of an even more colorful figure that captures the central dynamic of the Reformation, namely, how to be right with God.

2. Stewart Brown, Thomas Chalmers and the Godly Commonwealth in Scotland (1982).

A scrupulously researched inquiry that situates a hero of Scottish Calvinism within the political, educational, and ecclesiastical complexities of nineteenth-century Scotland.

3. Harry S. Stout, The Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism (1991).

A provocative account that looks past hagiography to capture the human (and sometimes unflattering) aspects of Protestantism’s greatest evangelist.

4. Terry Teachout, The Skeptic: A Life of H. L. Mencken (2002).

Arguably the best biography of the infamous literary critic in part because the author, a music critic, takes into account the subject’s love of music.

5. Bruce Gordon, Calvin (2009).

A smartly conceived narrative that allows Calvin’s “greatness” to emerge not from hindsight but from the accidents of sixteenth-century Europe.

Sean Michael Lucas is senior minister at The First Presbyterian Church, Hattiesburg, MS, and previously taught church history at Covenant Theological Seminary. Among his books is a biography of Robert Lewis Dabney: A Southern Presbyterian Life (P&R, 2005).

Sean Michael Lucas is senior minister at The First Presbyterian Church, Hattiesburg, MS, and previously taught church history at Covenant Theological Seminary. Among his books is a biography of Robert Lewis Dabney: A Southern Presbyterian Life (P&R, 2005).

Here are his top five picks:

1. D. G. Hart, Defending the Faith: J. Gresham Machen and the Crisis of Conservative Protestantism in Modern America (Johns Hopkins, 1994; reprint, P&R).

2. Allen Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President (Eerdmans, 1999).

3. Bruce Gordon, Calvin (Yale, 2009).

4. Harry S. Stout, A Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism (Eerdmans, 1991).

5. George Marsden, Jonathan Edwards: A Life (Yale, 2003).

“This is an odd list. I think the one common thread is that these are all intellectual biographies that pay attention to the way that their ideas or actions operated within their cultural systems. Another is that they all (except for Gordon) influenced the way I thought about biography when I went to write my Robert Lewis Dabney: A Southern Presbyterian Life (P&R, 2005).”

Kevin DeYoung is senior pastor at University Reformed Church in East Lansing, MI, and a PhD candidate at the University of Leicester, studying John Witherspoon under John Coffey.

Kevin DeYoung is senior pastor at University Reformed Church in East Lansing, MI, and a PhD candidate at the University of Leicester, studying John Witherspoon under John Coffey.

Here are his picks:

1. Allen C. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President (Eerdmans 1999).

This book shines because Guelzo is an excellent writer, with a knack for penetrating insights and fresh interpretations. I felt like I got to know Lincoln, so much so that by the end I was terribly sad when he showed up at Ford’s Theater.

2. Paul C. Gutjahr, Charles Hodge: Guardian of American Orthodoxy (Oxford 2011).

While I don’t agree with every conclusion in the book, it is a great example of an academic biography that is eminently readable. The chapters are short and the story moves at a good pace. Gutjahr is sympathetic to Hodge without being uncritical.

3. David McCullough, John Adams (Touchstone 2001).

The guy can flat-out write. No one does popular (yet substantive) biography as well as McCullough.

4. Paul Johnson, Churchill (Viking 2009).

Johnson demonstrates that you can write meaningfully about a massive subject in a short biography (181 pages). This book is especially strong in the lessons it draws from Churchill’s life.

5. D.G. Hart, Defending the Faith: J. Gresham Machen and the Crisis of Conservative Protestantism in Modern America (P & R Publishing, 2003).

Hart writes lucid prose about a figure he knows inside and out. By helping us understand Machen, we come to understand an entire era in American church history.

October 1, 2013

Live Like a Narnian: Christian Discipleship in C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles

Joe Rigney, Assistant Professor of Theology and Christian Worldview at Bethlehem College and Seminary and the author of the new book, Live Like a Narnian: Christian Discipleship in C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles, gave a compelling breakout talk at the Desiring God National Conference on this theme:

Audio here.

15 Biography Recommendations: Thomas Kidd, John Fea, and Doug Sweeney

Thomas Kidd is professor of history at Baylor University and Senior Fellow at the Institute for Studies of Religion. Among other works, he is the author of Patrick Henry: First Among Patriots and a major biography due out next year from Yale University Press on George Whitefield (marking his 300th birthday).

Thomas Kidd is professor of history at Baylor University and Senior Fellow at the Institute for Studies of Religion. Among other works, he is the author of Patrick Henry: First Among Patriots and a major biography due out next year from Yale University Press on George Whitefield (marking his 300th birthday).

He writes, “I am focusing on biographies from the colonial and Revolutionary eras of American history. I heartily agree with Mark Noll’s recommendation of my doctoral adviser George Marsden and his Jonathan Edwards biography, which would otherwise be at the top of my list. Since he’s already mentioned it, here’s the next five.”

1. David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride (Oxford University Press, 1994).

Fischer not only offers an evocative treatment of Revere and his world—which was more interesting than what Longfellow’s “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” told us—but one of the best books on the American Revolution, period.

2. Kenneth Silverman, The Life and Times of Cotton Mather (Harper and Row, 1984).

A Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of one of the most intense (some might say neurotic), prolific, and tragic of all the American Puritans. Reading this will help you understand why one of his opponents once firebombed Mather’s house!

3. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812 (Knopf, 1990).

Another Pulitzer Prize-winner, Ulrich’s remarkable recreation of Ballard’s compelling life is perhaps the best American social history biography ever written.

4. John Demos, The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America (Knopf, 1994).

This is a biography of the Williams family, especially of Eunice Williams, who fell victim to a 1704 Native American raid on Deerfield, Massachusetts. Demos tells the poignant story of how the seven year old Eunice grew up among the Mohawks, married an Indian man, accepted Catholicism, and never returned to the Puritan fold in spite of fervent appeals by generations of her family.

5. Catherine Brekus, Sarah Osborn’s World: The Rise of Evangelical Christianity in Early America (Yale University Press, 2013).

As I wrote in my review for The Gospel Coalition, Brekus’s extraordinary portrait of Osborn may be the best biography we have of an American evangelical woman.

John Fea is associate professor of American history and chair of the history department at Messiah College in Grantham, PA, and the author most recently of Why Study History? Reflecting on the Importance of the Past (Baker Academic, 2013).

John Fea is associate professor of American history and chair of the history department at Messiah College in Grantham, PA, and the author most recently of Why Study History? Reflecting on the Importance of the Past (Baker Academic, 2013).

1. Debby Applegate, The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher.

A vivid portrayal of 19th-century culture through the life of a member of one of the century’s most famous families.

2. Richard Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling.

Bushman brings the founder of Mormonism to life with elegant prose and scholarly insight.

3. Robert Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York.

Caro is known today for his biographies of Lyndon B. Johnson, but this earlier biography of the urban planner and landscape architect who “built” 20th century New York City reads like a novel.

4. George Marsden, Jonathan Edwards: A Life.

The best biography of Edwards ever written and a model for religious biography.

5. Eric Miller, Hope in a Scattering Time: A Life of Christopher Lasch.

Miller’s bio of late-twentieth century cultural critic and historian Christopher Lasch is one of the best intellectual biographies I have read.

Douglas Sweeney is professor and chairman of church history and history of Christian thought at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, as well as director of their Jonathan Edwards Center. Among his books is the very helpful Jonathan Edwards and the Ministry of the Word: A Model of Faith and Thought.

Douglas Sweeney is professor and chairman of church history and history of Christian thought at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, as well as director of their Jonathan Edwards Center. Among his books is the very helpful Jonathan Edwards and the Ministry of the Word: A Model of Faith and Thought.

1. Roland Baiton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther.

It remains the most widely read bio of Luther for good reason. It is a wonderful read on the most important Protestant pastor in history.

2. Skevington Wood, The Burning Heart: John Wesley: Evangelist.

Readers can feel Wesley’s heart burning on almost every page.

3. Peter Brown, Augustine of Hippo: A Biography.

Brown has spent his career recreating the world of late antiquity. This biography places our most fecund doctor of the church in that context beautifully.

4. George Marsden, Jonathan Edwards: A Life.

This is the definitive biography of our most important evangelical intellectual.

5. Alister McGrath, C. S. Lewis—A Life: Eccentric Genius, Reluctant Prophet.

This brand-new book makes great use of the recently released correspondence of Lewis, making this late-modern evangelical hero come to life (warts and all) for his fans.

Carl Trueman: 5 Recommended Biographies

Carl R. Trueman is the Paul Woolley Professor of Church History at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia.

Carl R. Trueman is the Paul Woolley Professor of Church History at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia.

He is the author (among other books) of Histories and Fallacies: Problems Faced in the Writing of History and the forthcoming Luther on the Christian Life.

Here are the top 5 biographies he recommends:

1. Simon Sebag Montefiore, The Young Stalin (Vintage, 2008).

A prequel to Montefiore’s Stalin: Court of the Red Tsar, this is a fascinating study of the early development of the later Soviet dictator and proof of the maxim that the child is father of the man, even when the man is named Joseph Stalin.

2. Michael Korda, Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia (Harper Perennial, 2011).

The most readable of many biographies of T.E. Lawrencs, the ultimate intellectual man of action and a personal hero.

3. Sheridan Gilley, Newman and His Age (Darton, Longman and Todd, 2002).

Ian Ker’s is surely the definitive biography of John Henry Newman but I give this the edge as being more readable and as offering a fascinating portrait not simply of the most influential religious thinker of the nineteenth century but also of the era in which he lived.

4. D.G. Hart, Defending the Faith: J. Gresham Machen and the Crisis of Conservative Protestantism in Modern America (P & R Publishing, 2003).

An important study of a key figure in the fundamentalist-modernist debate which also helps to demonstrate why the simple polarities of liberal/conservative are incapable of capturing the nuances of what actually happened.

5. Heiko Oberman, Luther: Man Between God and Devil (Yale, 2006).

Oberman’s most brilliant, speculative, flawed, and thought-provoking book is a fascinating study of the Luther as a late medieval figure. Blending social history, textual study, theology, philosophy, and psychology in a fascinating mix, this is the book which transformed my own thinking about Luther.

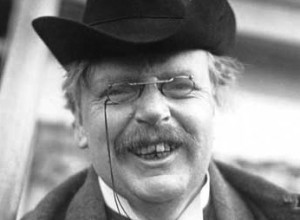

The Puritans Were More Chestertornian than Their Catholic Adversaries

So says C. S. Lewis:

So says C. S. Lewis:

[T]here is no understanding the period of the Reformation in England until we have grasped the fact that the quarrel between the Puritans and the Papists was not primarily a quarrel between rigorism and indulgence, and that, in so far as it was, the rigorism was on the Roman side.

On many questions, and specially in their view of the marriage bed, the Puritans were the indulgent party; if we may without disrespect so use the name of a great Roman Catholic, a great writer, and a great man, they were much more Chestertonian than their adversaries.

—C.S. Lewis, “Donne and Love Poetry” [1938], in Selected Literary Essays (Cambridge University Press, 1979), p. 116.

HT: Doug Wilson

September 30, 2013

Fred Sanders: 5 Recommended Biogragraphies

Fred Sanders, a theologian who teaches the Great Books in the Torrey Honors Institute at Biola University and is the author most recently of Wesley on the Christian Life, offers his five recommended biographies (with a few runner ups).

Fred Sanders, a theologian who teaches the Great Books in the Torrey Honors Institute at Biola University and is the author most recently of Wesley on the Christian Life, offers his five recommended biographies (with a few runner ups).1. Richard Heitzenrater, The Elusive Mr. Wesley (2nd edition).

In a feat of editorial bravura, Heitzenrater gives the reader first John Wesley in Wesley’s own words, then Wesley as reported by diverse contemporaries, and finally Wesley as reported by previous biographers (hagiographers and haters alike). There are a lot of good Wesley biographies, some more comprehensive, more theologically alert, or more narratively compelling than this one. But Heitzenrater uniquely accomplishes his goal of making you feel like you’ve encountered John Wesley himself.

2. Peter Brown, Augustine of Hippo (2nd edition).

Exquisitely well written, Brown’s book rises above merely reporting the stages along the way of Augustine’s life—though it narrates them well, so readers who need the basic facts can use this as an introduction—and somehow lets the reader empathize with Augustine at each of his different ages. They’re all here: the wild youth who wanted “chastity . . . but not yet,” the ladder-climbing young professor of rhetoric, the idealistic convert, the pastor who had to adapt his theology to the needs of the masses, the celebrity bishop pushed into more and more responsibility, and the consolidator of Christian orthodoxy as the lights of Rome were winking out.

3. Handley Moule, Charles Simeon

Reading Moule on Simeon is a double dose of spiritual insight. Moule was the great evangelical bishop of Durham and a Cambridge don. His telling of the life of Charles Simeon is deeply sympathetic, yielding wonderful insights into the character and spirituality of the preacher whose fifty-year pastorate transformed the ministry of preaching among British evangelicals and beyond. I admit, Moule can occasionally wander a bit and let the timeline become obscure. But I pretend I’m listening to a conspicuously saintly grandfather, and let him ramble. A better biography wouldn’t be able to impart what Moule can, so it wouldn’t be better.

4. Rudolph Nelson, The Making and Unmaking of an Evangelical Mind: The Case of Edward Carnell

This is an example of a biography that imposes a strong interpretive agenda on its subject: the author, Nelson, has apparently seen right through conservative evangelicalism and come out the other side into a space that may be minimal faith or no faith at all. He views the life and tragic death of Fuller Seminary president Edward Carnell as a case study in how evangelical thinkers are forced to engage in high-stakes “cognitive bargaining” with the massive plausibility structures of modernity, and are doomed to defeat. Why would I recommend a book that starts from all the wrong premises and risks distorting its subject so much? Because I can’t remember a biography I’ve argued more vigorously with, and the argument, perhaps despite itself, forces the reader to confront what were after all the main issues Carnell set himself to address.

5. Genevieve Foster, Augustus Caesar’s World

This is a book for young people, and yes, it’s illustrated. Foster focuses on the life of Augustus, but she also looks all over the world and describes what’s happening elsewhere during the years that Augustus is rising and ruling Rome. Foster emphasizes interconnections and simultaneity, and may have been a believer in synchronicity. But what you get in all her history books is an accessible, entertaining, and informative presentation of the things you vaguely feel you should have learned in high school.

Honorable Mentions

Honorable mention goes to the massive, exhaustive, definitive biographies that are too easy to get lost in the details of: Bethge on Bonhoeffer, Torrell on Aquinas, MacCulloch on Cranmer. They tell more than I wanted to know!

Approaching but not crossing that line are the exhaustive-but-readable Marsden on Edwards and Busch on Barth.

Bruce Gordon: 5 Recommended Biographies

Bruce Gordon, Titus Street Professor of Ecclesiastical History at the Divinity School of Yale University, is the author (among other books) of a major biography simply entitled Calvin (Yale University Press, 2009), “a biography that seeks to put the life of the influential reformer in the context of the sixteenth-century world. It is a study of Calvin’s character, his extensive network of personal contacts and of the complexities of church reform and theological exchange in the Reformation.”

Here are five biographies he recommends:

1. Peter Russell, Prince Henry “the Navigator”: A Life (Yale, 2001).

Russell’s command of every detail, from ship construction to tribes in Senegal, is evident at every point in this beautifully written and compelling tale.

2. Claire Tomalin, Samuel Pepys: The Unequalled Self (2002).

The book captures the vivacity, wit, and debauchery of Pepys through a sympathetic account of his life in the fast-paced world of Restoration England.

3. George M. Marsden, Jonathan Edwards: A Life (2003).

From start to finish, pure elegance of prose and a magisterial command of Edward’s thought and character.

4. Rüdiger Safranski, Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography (2002).

Focuses on a brilliant and tortured mind while telling the life of a remarkable man: a rare balance of narrative and philosophical discussion.

5. Jonathan Bate, John Clare: A Biography (2003).

An extraordinary nineteenth-century English poet from the laboring class who achieved brief fame in London before descending into the hell of mental illness.

An Interview with Andy Crouch about the Idol and Gift of Power

Andy Crouch, executive editor of Christianity Today and the author of Culture Making: Recovering Our Creative Calling (IVP, 2008), has a new book: Playing God: Redeeming the Gift of Power (IVP, 2013).

He was kind enough to answer some questions about his new book and the neglected topic of power—and what we can learn about it from the painting of a banjo lesson.

How would you describe the relationship between your books Culture Making and Playing God?

They definitely have a family resemblance. Both of them, at heart, are about what it means to be a human being, especially a flourishing human being. Both of them are informed by sociology more than any other academic discipline (outside the theological disciplines). And I hope both of them manage to treat huge topics (culture and power, respectively) in ways that apply to “ordinary” people. One theme of Culture Making was that all of us, not just cultural elites, have the opportunity and responsibility to cultivate and create culture; a key theme of Playing God is that all of us, not just the “powerful,” have real power and the responsibility to use it well.

That being said, there are some pretty big differences. Playing God has a bit more of a critical edge to it. With Culture Making, I felt it was important to counter a pervasive Christian pessimism about culture with a positive, hopeful account. Playing God certainly is a hopeful book—because there is also a pervasive Christian pessimism about power that I am trying to counter—but it deals much more directly, and at more length, with exactly what has gone wrong in the human story. Idolatry and injustice are the biblical categories for the failure of human cultures and human beings’ misuse of power, and I spend quite a bit of time unpacking them and examining both ancient and contemporary forms of the most disturbing kinds of idolatry and injustice. That’s just what comes with the territory if you want to be honest about how far astray our use of power has diverged from God’s original intent.

Playing God also goes deeper, I think, into the theological matters at the heart of both culture and power. The overarching argument of the book is that we will never understand power—either its possibilities or its distortions—until we understand the significance of human beings being created in the image of God. This idea of bearing the image is so incredibly theologically fruitful, and has so many profound resonances and implications, that it ended up taking over the book, in a good way I think.

I have heard a lot of sermons, and read a lot of books, articles, and blog posts, on imitating certain attributes of God and the incarnate Christ (e.g., compassion, love, goodness, mercy, humility). And I have heard a lot and read a lot about avoiding certain vices that are contrary to the kingdom (e.g., selfishness, envy, pride, lust). But I can’t recall offhand hearing much of anything about power—either as a gift to be redeemed or an idol to be rejected. You’ve invested a significant amount of time now thinking about the redemption of power to promote flourishing for the common good. Why do you think the Church has neglected this topic in particular?

That is what prompted me to write this book: a dawning awareness that I was almost never hearing Christians—especially in the dominant culture—directly address power as either a gift or an idol. Now, that is not at all the case in many minority-culture communities. I’ve spent perhaps 50 Sunday mornings of my life, cumulatively, in African-American church settings, and I’d bet that at least a third of sermons I’ve heard in those settings have directly addressed power and powerlessness in the context of American society, and how Christians should respond to those realities.

But of the couple thousand Sundays I’ve spent in majority-culture church settings, I could count on one hand the times the teaching directly addressed those topics. But the privilege of being in a majority is you rarely have to examine your own power closely. You often are not even aware that you have it. Oddly, power is frequently most invisible to the powerful—especially the form of power that I call privilege. So perhaps it is not surprising that majority-culture Christians rarely address it.

Power is a truly tricky topic, and that’s another reason you don’t hear a lot about it directly. Like the Holy Spirit, which in turn is like the wind, it is much easier to perceive power’s effects than the thing itself—in fact, you only know power by its effects.

The concept of flourishing is crucial for your book. What does it mean to flourish, and why is power such a key means and threat for the promotion of human flourishing?

I think of flourishing as fullness of being—the “life, and that abundantly” that Jesus spoke of. Flourishing refers to what you find when all the latent potential and possibility within any created thing or person are fully expressed. In both Culture Making and Playing God I talk about the transition from nature to culture as a move from “good” to “very good.” Eggs are good, but omelets are very good. Wheat is good, but bread is very good. Grapes are good, but wine is very good. Et cetera. And the Bible has a third category, which is glory, which I would define as the magnificence of true being, a kind of ultimate flourishing. It is significant that the New Jerusalem will be full both of the glory of God—the magnificence of God’s true being fully known, experienced, and worshipped—and “the glory and honor of the nations”—which I take to mean the fruits of human culture brought to their deepest and fullest expression.

The interesting thing is that flourishing never happens by accident. Intentionality is always involved. And for most parts of creation, intelligent, attentive cultivation is required for things to flourish. If wine is one “very good,” flourishing expression of the grape, well, you don’t get wine if you just let it ferment on its own—you get vinegar, or worse. Wine only comes with tremendous skill, patience, and indeed creativity.

And this is why power is so intimately connected to flourishing—flourishing requires the exercise of true power, power that is bent on creating the best environment for someone or something to thrive. And while human flourishing is of paramount importance, the witness of Scripture seems to be that we human beings are here not just for our own flourishing, but for the flourishing of the whole created order. I think this is why Paul says the creation is “groaning for the revealing of the sons of God”—that phrase “sons of God” (which of course includes redeemed image bearers both male and female) is meant to signal true authority and dominion. If the true “sons of God” were to be revealed, the creation would flourish in ways we only dimly glimpse now.

In the book you illustrate the gift of power by reflecting on your ongoing and awkward attempt to learn to play the cello as an adult as you observe the dynamic interplay of information and power in the relationship between you and your teacher. Even though you don’t use this illustration in the book itself, I know you have found Henry Ossawa Tanner’s painting, “The Banjo Lesson” (1893), to be instructive.

When did you first come across this painting, and when did you begin to make the connection between Tanner’s vision and the meaning of true power?

I’ve ended both books with a reflection on a painting (in Culture Making it was Rembrandt’s “The Artist in His Studio”). I had planned to end Playing God with “The Banjo Lesson”—and then Rublev’s “Trinity” took over!

But Tanner’s painting is an amazing portrait of true power, in the context of a music lesson. I first seriously encountered “The Banjo Lesson” in a seminar I led at the Glen Workshop in Santa Fe in 2009. One of the participants, Doug Learned, gave an amazing presentation about Tanner’s work—Tanner was not only the first African-American painter of international renown but arguably the last American painter of that stature to be a serious and devout Christian.

What really got me thinking about Tanner’s painting is the two levels on which it operates. At one level, it is simply a portrait of the exchange of power that happens in all musical instruction (and instruction more generally), where the student acquires power without the teacher giving up any of their own power. Teaching is a paradigmatic example of how power can multiply and lead to flourishing without anyone being diminished or dominated. The teacher has real, asymmetrical power, capacity, and authority—something we too easily automatically associate with domination—but that authority is all devoted to the flourishing of the student. And yet the teacher also flourishes in that relationship, precisely by exercising power. Tanner captures the intimacy, trust, love, and patience involved in the true use of power for flourishing—and by including a jug and loaf on the golden-lit table in the background, suggests that what is happening here is not just mundane culture but a foretaste of glory.

At another level, Tanner was operating within a profoundly broken system of power, the system that sustained (and sustains) racism in the United States. The banjo was not a neutral cultural artifact—it was a kind of shorthand in the dominant culture for African-American (“Negro”) culture. The banjo was the instrument of vaudeville and blackface, of Sambo-style jovial entertainment offered up for the consumption of white audiences.

By painting a banjo lesson, Tanner was taking this visual symbol of the exploitation of his own culture and rescuing it from caricature and diminishment. He infuses this humble musical instrument and art form with all the artistry of the salons of Paris and all the dignity of “classical” instruments (like, say, the cello). I see this painting as a kind of restoration of image-bearing possibility—it restored dignity, agency, and beauty to a culture and a people who had been robbed of them.

And if you know African Americans of a certain age, almost all of them had an aunt or grandmother who had a print of Tanner’s Banjo Lesson in her home—it became incredibly popular in the Black community. For good reason—it is an African American artist, at the height of his talents, restoring the image of his own community. Tanner never wanted to be limited to painting “African-American” scenes, and in a way that makes this painting more powerful. He was not a genre painter. But when he turned to this subject, he brought all his skill and power to restoring others’ image-bearing capacity. That is true power.

What do you see in this painting that teaches us about the relationship of power to teaching, learning, and knowing?

At the first level, it says that power is meant to be shared, just as it is shared in this painting the older man and the young boy, with the beautiful depiction of cooperation—the man’s hand supporting the banjo’s neck while the boy plays; the boy on the older man’s lap, legs dangling down; their heads bent in attentive listening.

True power seeks relationship. Idolatrous, dominating power avoids and fears relationship. But true power is meant to be embedded in relationships of mutual trust, submission, and creativity—which is surely why we get that amazing “Let us make” at the climax of Genesis 1, the opening chapter of the founding document of monotheism! The true God is not a solo god. The true God is Trinity. And so all power, to be true and life-giving power, is exercised in the context of love.

At the deeper level, it says that in the world we have, broken and distorted as it is, one of the best uses of our power (like Tanner’s artistic power) is to restore the image-bearing capacity of the vulnerable, the least, and the poor. You can see the whole mission of God from Genesis 12 onward through Scripture as an image-restoring mission: calling forth a people who would image him, and restore his image, in a world full of idols and injustice; coming among them in incarnate, human form, the form of the “image of the invisible God” (Col. 1); and pouring out his Spirit on the church so that we, too, now bear the image and redeeming power of Christ in a world full of broken images.

You contrast the vision of non-idolatrous redemptive power with the Nietzschean zero-sum understanding of power often exemplified in Western movies. Though learning to play an instrument may seem like a minor thing—especially if we will not go on to play it professionally—you see it as a way in which power can be expanded if it is shared. Can you explain?

Nietzsche had a relentlessly zero-sum conception of power as domination: if you have more power, I have less. And ultimately he thought the goal of every body was to utterly fill and control all space, to the exclusion of other bodies.

I think we, as Christians, have to insist that Nietzsche’s vision is ultimately false—though it rings all too true in the world that we have. And in music we get hints, at so many levels, that true power is not exclusive, does not require domination and control to be fully expressed. There is the remarkable property of musical notes to coexist, as Jeremy Begbie pointed out in Theology, Music and Time: a chord is a set of notes sounding simultaneously and harmonizing in ways that make the chord much more than just the sum of its parts.

I studied the piano extensively, and eventually played it professionally, but the cello has introduced me to something you rarely experience as a pianist. In my cello lessons, I’ll be sitting side by side with my teacher, and when he plays a note or scale, my cello starts resonating even if I’m not playing. It’s just how the physics works—strings start vibrating in harmony with one another. When we play a piece together, in unison or harmony, the complex interaction between the two instruments, not to mention the two persons bringing their skill (at different levels!) to the performance, leads to a rich, flourishing sound you cannot get with a single instrument.

It might seem foolish to put music up against Nietzsche or Machiavelli, as if that experience of harmony is enough of a counterweight to the terrible reality of violence and coercion used in our world to master and dominate. But music is one of the deepest and most profound expressions of human culture (and was, oddly and incidentally, one of Nietzsche’s great loves). It is a cultural universal—present in some form in every culture. Few things can reach or move us the way music can—for all its invisibility and insubstantiality, it has power in a very real sense. So why wouldn’t it be a clue to the nature of true reality, a reality deeper and realer than Nietzsche’s world of competition and domination?

Obviously, to use power well in this world we have to move beyond just music lessons. But music lessons, with their harmony, cooperation, mutual submission, discipline—and joy and delight—are not a bad place to start reconceiving what we think power is about, what it is for, and just how good and even glorious it was meant to be, and one day will be.

September 27, 2013

George Marsden: 5 Recommended Biographies

George M. Marsden is Professor of History, Emeritus, at the University of Notre Dame.

George M. Marsden is Professor of History, Emeritus, at the University of Notre Dame.

Among other books, he is the author of the award-winning, definitive biography on Jonathan Edwards: A Life (Yale University Press, 2003).

Here is his list of recommended biographies, in alphabetical order of subject:

1. Peter Brown, Augustine of Hippo.

A classic work and a great exposition of the man and of his era.

2. Robert Caro, Master of the Senate: The Years of Lyndon Johnson.

Wonderful example of the art of great story telling.

3. Walter Lowrie, A Short Life of Kierkegaard.

Probably dated by now, but a great brief introduction to a most complex figure

4. James D. Bratt, Abraham Kuyper: Modern Calvinist, Christian Democrat.

New biography. Wonderfully balanced account about a multifaceted thinker and leader still important for today.

5. Richard Westfall, Never at Rest: A Biography of Isaac Newton.

Excellent at presenting Newton’s thought in the context of its times.

Allen Guelzo’s Top 5 Biographies

Allen C. Guelzo is the Henry R. Luce Professor of the Civil War Era and Director of the Civil War Era Studies Program at Gettysburg College. He began his scholarly career working on Jonathan Edwards (Edwards on the Will: A Century of Theological Debate [1989] was a revision of his doctoral dissertation). His 1999 biography of Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President won the prestigious Lincoln Prize, as did his Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America. More recently he has written a new history of the Civil War, and his latest book is on the battle of Gettysburg.

Allen C. Guelzo is the Henry R. Luce Professor of the Civil War Era and Director of the Civil War Era Studies Program at Gettysburg College. He began his scholarly career working on Jonathan Edwards (Edwards on the Will: A Century of Theological Debate [1989] was a revision of his doctoral dissertation). His 1999 biography of Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President won the prestigious Lincoln Prize, as did his Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America. More recently he has written a new history of the Civil War, and his latest book is on the battle of Gettysburg.

Here are five biographies he believes represent the genre at its best.

1. Perry Miller, Jonathan Edwards (1949).

Although lopsided in its effort to place Edwards in the stream of John Locke, Miller’s Edwards is a work of real literary genius.

2. Richard S. Westfall, Never at Rest: A Biography of Isaac Newton (1980).

A glowingly comprehensive and sympathetic biography of one of the greatest of scientific minds.

3. Peter Brown, Augustine of Hippo (1967).

A stupendously erudite re-creation, not only of Augustine, but of the entire world of late antiquity.

4. Edmund S. Morgan, The Puritan Dilemma: The Story of John Winthrop (1962).

A short but wickedly-well-written biography of the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay colony, done with surprising sympathy.

5. Henry D. Rack, Reasonable Enthusiast: John Wesley and the Rise of Methodism (1989).

No other single work on Wesley and 18th-century England captures the times and the man so well.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers