Justin Taylor's Blog, page 107

May 2, 2014

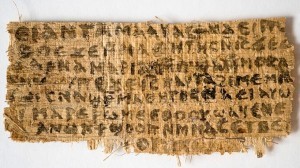

Why the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife Fragment Is a Forgery

Brad Green, writing at Tyndale House in Cambridge:

Brad Green, writing at Tyndale House in Cambridge:

Much of the New Testament scholarly world is abuzz concerning a purportedly ancient Coptic fragment, which has been called The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife. Is it truly ancient? A forgery? The most recent volume of Harvard Theological Review is devoted to this fragment with articles by Dr Karen King of Harvard Divinity School, who has been the driving force behind the announcement and dissemination of this fragment.

Dr Christian Askeland, who earned his Ph.D. at Cambridge University while living at Tyndale House, has recently written what Mark Goodacre calls a ‘devastating‘ critique of the authenticity of The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife. Askeland has helpfully summarized the issues.

May 1, 2014

Free Audiobook of the Month: J.I. Packer’s “Evangelism and the Sovereignty of God”

An Interview with James K. A. Smith on How (Not) to Be Secular and How (to) Read Charles Taylor

The latest book by James K. A. Smith, professor of philosophy at Calvin College, releases today and is entitled How (Not) to Be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor (Eerdmans, 2014), interacting with and applying Charles Taylor’s magisterial volume, A Secular Age (Harvard University Press, 2007).

The latest book by James K. A. Smith, professor of philosophy at Calvin College, releases today and is entitled How (Not) to Be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor (Eerdmans, 2014), interacting with and applying Charles Taylor’s magisterial volume, A Secular Age (Harvard University Press, 2007).

Of Smith’s book Tim Keller writes, “As a gateway into Taylor’s thought, this volume (if read widely) could have a major impact on the level of theological leadership that our contemporary church is getting. It could also have a great effect on the quality of our communication and preaching. I highly recommend this book.”

Professor Smith was kind enough to answer a few questions.

Who is Charles Taylor and why should we care about what he has written?

Taylor (b. 1931) is a Canadian philosopher who taught for decades at McGill University in Montreal, though he also held appointments at Oxford and Northwestern over the years. Over the past several years, his work has made a significant impact on my own. I think this is because he sort of “contains multitudes,” as Whitman might say. He is a unique blend of scholar. Taylor is a philosopher who is equally at home in both “analytic” and “continental” camps. But he also puts his philosophical expertise to work on cultural analysis, ranging into history, theology, psychology, economics, and more. Of course, this also gets him into trouble with the specialists, but that’s the price one pays for being a fox and not a hedgehog.

Finally, Taylor is a serious Christian public intellectual. He is a Catholic philosopher who is willing to take a stand for his faith, and also willing to argue that his faith perspective makes a difference for theorizing. Indeed, Taylor is an “apologist” of sorts, one who is nuanced, complex, humble, with right-sized expectations of what one can hope to accomplish. Lots of evangelicals are quite fascinated with “apologetics”; I wish more of them were interested in apologists like Taylor.

What makes his writing inaccessible for many readers?

Ha, good question! I think it’s a combination of things. First, there is just the sheer daunting size of big books like Sources of the Self and especially A Secular Age (900 pages!). Not for the faint of heart. Second, in later books like these, Taylor’s “method” is essentially narratival: he’s helping us make sense of our present by offering an account of our past. He’s kind of a genealogist. So his arguments wend and wind through nooks and crannies of cultural history that can often be foreign to us.

I have a couple of my own idiosyncratic hypotheses about his difficulty. For example, I wonder if there’s something about Taylor’s bilingual fluency that actually generates English prose that is kind of tortured. (I find the same experience reading Dutch philosophers for whom English was a second language.) And, to be honest, I think Taylor’s editors at Harvard University Press were just somehow too intimidated by him or something (or maybe Taylor was stubborn!). Because A Secular Age could have been a much better book if it was 2/3 the length.

That said, it’s not like he’s unreadable. I suggest reading him while listening to Arcade Fire’s “The Suburbs.” There’s something mutually illuminating in the Quebec connection and their shared sense of “the malaise of modernity”! If that doesn’t work, trying reading some Derrida for a while, and then pick up Taylor. That’ll make Taylor seem clear as day!

What is Taylor’s thesis on secularism?

Taylor offers a different taxonomy for understanding “the secular,” secularism, and secularity. Most of us, including those who touted “secularization theory,” identify secularization with a-religiosity. In other words, something or someone is “secular” in the sense that they “don’t believe,” are not “religious.” I think this is one of the reasons why outlets like the New York Times or The New Republic can just talk about about religious people as “believers,” whereas everyone else—that is, the editors of NYT and TNR!—are not.

If you buy this sort of notion of secularization, then modernity is what Taylor calls one big “subtraction story”: modern Enlightenment rationality is what’s left over when you subtract the superstition of religious belief. Subtract religion, and what you’re left with is “secular” rationality.

Taylor doesn’t buy this because, as he tries to show, modernity was not just about the subtraction of God and religious belief; it also required the substitution of something to take its place—what he calls “exclusive humanism,” the belief that one can find meaning and significance without any recourse to the gods of transcendence. For Taylor, even though he ultimately disagrees with it, this is the productive accomplishment of modernity: exclusive humanism is a remarkable feat of addition, not the remainder of some subtraction.

You’ll note what’s embedded in his point: exclusive humanism is something you have to believe. So the world is not carved up into “believers” and “secular” rational knowers. It’s a complicated array of different sorts of believers. And that’s why Taylor calls ours a “secular” age: not that we are a-religious or no longer believe, but that we live in an age in which no belief system is axiomatic. Our beliefs are contestable, and we know it.

What motivated you to write this book about a book?

I taught a senior seminar on A Secular Age with a group of intrepid Calvin College philosophy majors who ploughed through the book with me. In the course of our discussions, it was clear that something in Taylor’s analysis struck an existential chord for them: it helped them make sense of the fraught world they inhabit. As I spent more time with Taylor’s book, I also realized that this would help lots of pastors and church planters better understand “secular” environments like New York or Seattle or Austin. But I realized—and completely understand!—that pastors and practitioners don’t have the time to wade through Taylor’s huge book, so I wanted to try to crystallize and compress his analysis and tie it to some contemporary cultural hooks in a way that could help those who find themselves immersed in such contexts.

I’ve talked elsewhere about the necessity for pastors to be ethnographers; I think Taylor’s argument—and hopefully my book—can equip them to do that a little better. I also hope it reframes what it means to engage a “secular” context. If Taylor is right, this shouldn’t be seen as a battle. Instead, we should recognize all the persistent longings for transcendence that characterize our secular age. To proclaim the Gospel in such a context is not a matter of guarding some fortress; it’s an opportunity to invite our neighbors to meet the One they didn’t even realize they’d been longing for.

How does Taylor, as a Catholic, understand the Reformation in light of his thesis on secularism, and what do you think about his understanding in light of your own Reformed theology?

This is an important question. The answer is, “It’s complicated.”

On the one hand, Taylor is quite laudatory about the Reformation and deeply sympathetic. On his account, the Protestant Reformation is part of a broader, late-medieval “Reform” movement that calls into question versions of “two-tiered” Christianity that devalued the faith of laypeople. In Taylor’s formulation, part of the Reformation’s renewal was “the sanctification of ordinary life”—a sense that all of life would be lived coram Deo, before the face of God. So it wasn’t just priests and nuns who had “sacred” vocations; the same could also be true of butchers, bakers, and candlestick makers. Domestic, family life was just as “sacred” as cloistered celibacy, and so forth. For a Kuyperian like me, this sings of “every square inch,” if you know what I mean.

On the other hand, Taylor also argues that the Reformation introduced trajectories that would later lead to the “disenchantment” of the world. The story here is “Frankenstein-ish” in the sense that he sees this as an unintended outcome of what were good motives. (Dr. Frankenstein had the best of intentions!) While the Reformers rightly sought to reject superstition, the result was that they sort of de-sacramentalized creation and Christian worship. The world become ontologically “flat” rather than, as Gerard Manley Hopkins put it, “charged” with the grandeur of God. In other words, we’re all Zwinglians now. (Taylor is not the only one to make point this out; consider also the careful argument of historian of science, Peter Harrison, in his important book, The Bible, Protestantism, and the Rise of Natural Science.)

As a Protestant, I take this criticism very seriously, even if I might ultimately disagree. But before I defend Protestantism, I think it’s important to hear this and consider in what ways it is true. It should occasion some self-reflection for us. I think the work of J. Todd Billings, for example, is an example of a Reformed, Protestant theologian who, in some ways, is sympathetic to Taylor’s point, but then who shows that the Reformed tradition has resources—right there in Calvin—to counter this picture.

April 30, 2014

When We Are Not Robustly Trinitarian, Our Gospel Will Not Be Robustly Christian

Mike Reeves, author of Delighting in the Trinity: An Introduction to the Christian Faith, delivers a short and delightful talk on the necessary relationship between the gospel and the Trinity:

April 29, 2014

Why Some Teachers Are Banning Laptops from the Classroom

From the FAQ page of Alan Jacobs, Distinguished Professor of the Humanities in the Honors Program at Baylor University in Waco, Texas:

Is it okay if I bring my laptop to class to take notes?

No, sorry, not any more. Now that Baylor offers wireless internet access in most classrooms, the university has provided you with too many opportunities for distractions. Think I’m over-reacting? Think you’re a master of multitasking? You are not. No, I really mean it. How many times do I have to tell you? Notes taken by hand are almost always more useful than typed notes, because more thoughtful selectivity goes into them; plus there are multiple cognitive benefits to writing by hand. And people who use laptops in class see their grades decline — and even contribute to lowering the grades of other people. Also, as often as possible you should annotate your books.

Here’s another report of a new study on this:

A new study in Psychological Science, though, suggests there’s even more to laptops’ negative effects on learning than distraction. Go old school with a pen and paper next time you want to remember something, according to Pam Mueller and Daniel Oppenheimer of Princeton and the University of California-Los Angeles, respectively, because laptops actually make note-taking too easy.

The researchers ran a series of studies that tested college students’ understanding of TED Talks after they took notes on the videos either in longhand or on Internet-less laptops. Even without Facebook, the computer users consistently did worse at answering conceptual questions, and also factual-based ones when there was a considerable delay between the videos and testing.

You can read the whole thing here.

HT: @MatthewJHall

April 28, 2014

Why Does God Care Whom I Sleep With?

King’s Church in Eastbourne (East Sussex, England) has put together an excellent resource addressing the big objections.

Below is one of the talks delivered from Andrew Wilson (with a cameo from Sam Allberry). Wilson makes a three-step argument by asking three questions:

1. Everyone cares who people sleep with, so why would God be any different?

2. If there is a God and he has a timeless ethical standard, wouldn’t you expect it to challenge every society somewhere?

3. Finally, why do we care so much whom we sleep with?

You can watch the rest of the talks here.

April 25, 2014

Ethical and Theological Discourse in an Age Dominated by Advertising

And this is a key point, one which, having been raised without a television, it took me a while to recognize: the overwhelming majority of people today were trained in the process of making up their minds by advertisers. They also picked up the art of persuasion, not from classic texts of reason, but from advertising. As a result, many people fail to demonstrate genuine literacy in understanding and creating reasoned arguments, but are adept at producing advertising copy for their impressions. They have been taught both to process and to persuade using impressions. I think that Josh Strodtbeck expresses this well (I’ve quoted this before):

Then there’s this other type of person. As nearly as I can tell, they seem to create collages in their mind as they read. Turns of phrase here and individual metaphors there get thrown into different places in the collage until they have what appears to them to be a fairly complete picture, then they react to the picture in more of a qualitative way (this reaction is usually emotional since they don’t really do “critiquing logic” or “refuting ideas”). This sort of person really doesn’t do very well at all with complex writing, especially writing that goes in directions they’re not used to. In my experience, explaining what I wrote to a person like this is a lost cause. I inevitably find myself repeating ideas over and over, quoting my own text, and dissecting my own grammar to prove to this sort of person that I said what I actually said. If your audience is this sort of person, you need to be extremely careful in how you choose your individual words and phrases, or you will set off a negative emotional reaction that makes further communication impossible.

If you read many blogs, especially from a certain brand of progressive evangelical, you will notice similar styles of writing and thinking in operation. Sentences are brief, there are numerous single sentence paragraphs, sentences in bold, or fragmented statements. Anecdotes and engaging narratives are consistently employed. Rhetorical questions, potent images, and controlling metaphors are used extensively. Such writing typically persuades by getting the reader to feel something. The responses to such pieces are almost always emotive and affirming, very seldom critical (and critical responses are hardly ever interacted with carefully).

In an age dominated by advertising and the manipulation of feelings for the purpose of persuasion, the proliferation of conversational and self-revelatory styles of discourse, designed to capture people’s feelings, where logical argumentation once prevailed, shouldn’t surprise us. Where persuasion occurs through feeling, truth becomes bound up in the authentic communication of the ‘self’ and its passion, rather than in the more objective criteria of traditional discourses, where truth was tested by realities and practices outside of ourselves. This is truth in the mode of sharing one’s personal ‘sacred story’.

It is for this reason that narrative, anecdote, metaphor, and potent images are so important for such approaches. All of these are non-argumentative ways of drawing and inviting you, the reader, into the feelings of the text. They also serve as ways of avoiding direct ideological confrontation and engagement. By couching what would otherwise have to be presented as a theological argument in an impressionistic narrative they make it very difficult to frame disagreements. The most effective communicators of this type tend to be those who elicit and direct feelings most consistently. It can almost be as hard to have reasonable argument with such people than it would be to argue with an advert.

You can read the whole thing here (it’s excellent but very long!).

A Biblical and Theological Analysis of Near Death Experiences

A thoughtful outline from David W. Jones of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary:

Near Death Experiences by David Jones

April 24, 2014

A Conversation with Peter Williams on the Future of the Church

Peter Williams, head of Tyndale House in Cambridge, England, sits down to talk about the future of the church and the challenges it faces, how Christians should present God to others, Church unity and oneness within denominational diversity, the requirements for biblical scholarship, why Jesus was a carpenter, what faithfulness looks like in the Western world, how to identify false teaching, and encouragement to pastors:

Fading and Perishable Beauty vs True and Growing Beauty

From Carolyn Mahaney and Nicole Whitacre’s new book, True Beauty:

From Carolyn Mahaney and Nicole Whitacre’s new book, True Beauty:

While women in our culture thirst after what few drops of glory and goodness they can drain from physical beauty, they look older even as they try to look younger, more hollow and hardened even as they chase after an elusive happiness.

By contrast, the woman who pursues the godly woman’s True Beauty Regimen grows radiant as she looks to God in adversity (Ps. 34:5). She lights up the faces of those she serves, and most precious of all, she pleases our Savior.

Christ is the beautiful One. His glory and splendor, his sacrifice and salvation, define true beauty. It is not the world that defines beauty. It is not the latest fashions, or a photoshopped image, or an ideal body type. True beauty is, to the world, as incomprehensible as it is undeniable. . . .

For the Christian woman, each day brings us one step closer to true beauty. As earthly beauty fades away, imperishable beauty grows stronger and lovelier, and the most beautiful vision we will ever see draws nearer—the day when we will “behold the king in his beauty” (Isa. 33:17), when we will see our beautiful Savior face-to-face.

Until that beautiful day, let us gaze upon the beauty of the Lord all the days of our lives, and pursue a beauty that is precious in his sight.

True beauty is to behold and reflect the beauty of God.

You can find more information about this insightful and encouraging book here.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers