Justin Taylor's Blog, page 102

June 21, 2014

What’s Wrong with “The Wrong Side of History” Argument

The appeal to history is thus a nifty little piece of rhetorical violence, a ‘performative utterance’ that seeks to bring about the fate that it announces and to excuse the opposition’s loss of agency as the inevitable triumph of justice.

Upon inspection, “X is on the right side of history” turns out to be a lazy, hectoring way to declare, “X is a good idea,” by those evading any responsibility to prove it so.

We invoke the future’s verdict of guilt precisely because we’d like to smuggle back into our politics the moral force of Divine judgment. But our appeals to progress are a pathetic substitute for the concept of Providence. The former stifles critical reflection about the past. The latter is at least flexible enough to account for the sudden flowering of great evil, even in an age as advanced as ours.

What we do know from history is that the future often rejects the past. Political ideals are often abandoned, rarely refuted.

And so we are thrown back on ourselves. If your cause is just and good, argue that it is just and good, not just inevitable.

June 20, 2014

The Three Essential Characteristics of Marriage Universally Agreed Upon Until Recently

Up until very recently, marriage had been universally thought of as consisting of three essential characteristics: conjugality, permanence, and exclusivity. This had been more or less reflected in our laws.

Conjugality refers to the way by which a marriage is consummated: coitus between the male and female spouses.

Permanence means that the marriage cannot be dissolved (or annulled) unless certain specific conditions are met or one of the partners dies.

Exclusivity refers to the sexual relationship and means that neither party in the marriage is free to engage in extra-marital intimacies.

Even polygamous unions may fulfill these criteria, for the husband is married to each wife while the women are not married to each other and thus do not have “wives.” For this reason, upon the husband’s death, each of the marriages in a polygamous cluster is immediately dissolved.

Conjugality is only a condition because of the nature of sexual intercourse: it is ordered toward bringing into existence offspring of the union of the two parties. This is why handshakes, hugs, kisses, or other forms of bodily touching, penetration, or intimacy can never count as conjugality.

But this is also why it is wrong to say that the latter are indistinguishable from conjugal acts that cannot bring forth offspring due to illness or age. For such conjugal acts, though sterile, do not cease to be conjugal acts, just as a man in a coma does not cease to be a rational animal simply because he is not able to exercise his rational faculties.

Just as the comatose man still possesses human dignity even though he is not able to exercise his unique human powers, the conjugal act between a husband and wife that is incapable of conceiving possesses no less dignity precisely because it actualizes the same profound and mysterious union that is by nature ordered toward bringing into existence a unique and irreplaceable person that literally embodies that union.

You can read the whole thing here.

HT: Matt Franck

June 19, 2014

How to Maintain Pastoral Zeal While Avoiding Pastoral Burnout

Christopher Ash, director of Cornhill Training Course, speaking on May 13, 2014, at Truth for Life’s Basics conference, shares out of personal experience and from the Word:

How can burnout be a problem in ministry when Christ Himself encouraged His followers to give up everything for the sake of the Gospel? Christopher Ash explains that there is a vital difference between living sacrificially for Jesus and pursuing our calling in a way that leads to mental and physical exhaustion. When Christian leaders bear in mind that we are created by God from dust and that all of our endeavors are dependent on Him for success, we are reminded that Gospel ministry is a humbling privilege and enabled to rejoice that we are recipients of God’s grace in Christ Jesus.

You can watch the whole thing here:

For the audio, go here.

Ash mentions several books that may be helpful:

Peter Brain, Going the Distance: How to Stay Fit for a Lifetime of Ministry

John Hindley, Serving without Sinking: How to Serve Christ and Keep Your Joy

Paul Tripp, Dangerous Calling: Confronting the Unique Challenges of Pastoral Ministry

Vaughn Roberts, True Friendship: Walking Shoulder to Shoulder

Kent and Barbara Hughes, Liberating Christianity from the Success Syndrome

Marjory Foyle, Honourably Wounded: Stress Among Christian Workers

June 18, 2014

Why We Need to Teach Our Kids Poetry

William Logan, writing in last Sunday’s New York Times:

Poetry was long ago shoved aside in schools. In colleges it’s often easier to find courses on race or class or gender than on the Augustans or Romantics. In high schools and grade schools, when poetry is taught at all, too often it’s as a shudder of self-expression, without any attempt to look at the difficulties and majesties of verse and the subtleties of meaning that make poetry poetry. No wonder kids don’t like it — it becomes another way to bully them into feeling “compassion” or “tolerance,” part of a curriculum that makes them good citizens but bad readers of poetry. My blue-sky proposal: teach America’s kids to read by making them read poetry. Shakespeare and Pope and Milton by the fifth grade; in high school, Dante and Catullus in the original. By graduation, they would know Anne Carson and Derek Walcott by heart. A child taught to parse a sentence by Dickinson would have no trouble understanding Donald H. Rumsfeld’s known knowns and unknown unknowns.

You can read his whole op-ed here.

Anyone can make a child read a poem. But how can he or she learn to understand it? Further, how do we teach children to write poetry? Here is a new classical course on poetry:

The Grammar of Poetry homeschool curriuclum is a video course and textbook that teaches the mechanics of poetry by using the classical approach of imitation. It is designed for the 6-9th grade level, but is also appropriate for older children and adults seeking to achieve a better knowledge of how poetry works.

Its goal is to teach your child to analyze not only poetry, but words and language in general. Just as an English course would teach a student the different parts of speech, so also the Grammar of Poetry teaches a student the building blocks of poetry, enabling the student to effectively engage in the language of poetry, in literature, and in non-literal language.

This is the ideal introductory poetry course for students and teachers discovering the art of poetry. As a “grammar,” it teaches the fundamentals of poetry from scansion and rhyme to more advanced concepts like spatial poetry and synecdoche.

Using the classical methodology of imitation (advocated by educators like Quintilian and Benjamin Franklin), this text makes students become active participants as they learn the craft of writing poems.

It also offers practical tips and helps, including how to use a rhyming dictionary, how great writers use figures of speech effectively, and even when to break the rules of poetry. Its goal is to show students how to capably interact not just with poems, but with language in any situation.

Developed and used at Logos School with great success, the thirty lessons in Grammar of Poetry contain instruction on ten powerful tropes, student activities for every chapter, riddles to solve, a glossary of terms, a list of over 150 quality poems to integrate, and real-life examples from Shakespeare to traditional tongue twisters.

The teacher, Matt Whitling, is the principal of Logos School (one of the first classical Christian schools to resurface in the United States), and the author of the best-selling Grammar of Poetry textbook. He and his wife Tora live in Moscow, Idaho and have seven children.

Find out more here.

11 Theses on the Revelation of the Trinity

As I’ve been working on a large writing project on the doctrine of the Trinity (The Triune God in Zondervan’s New Studies in Dogmatics series), one of the things that has increasingly called for attention is the peculiarity of the way this doctrine was revealed. It’s simply not like other doctrines. I think the doctrine ought to be handled in a way that takes account of the way it was made known. More strongly: the mode of the revelation of the Trinity has structural implications for the right presentation of the doctrine. Here, in compressed form (propounded but not defended), are guidelines I’ve been working with for handling the doctrine.

Here are his theses (click through to read an explanation of each):

1. The Revelation of the Trinity is Bundled With The Revelation of the Gospel.

2. The Revelation of the Trinity Accompanies Salvation.

3. The Revelation of the Trinity is Revelation of God’s Own Heart.

4. The Revelation of the Trinity Must Be Self-Revelation.

5. The Revelation of the Trinity Came When the Son and the Spirit Came in Person.

6. New Testament Texts About the Trinity Tend to Be Allusions Rather than Announcements.

7. The Revelation of the Trinity Required Words to Accompany It.

8. The Revelation of the Trinity is the Extending of a Conversation Already Happening. 9. The Revelation of the Trinity Occurs Across the Two Testaments of the Canon.

10. The Revelation of the Trinity in Scripture is Perfect.

11. Systematic Theology’s Account of the Trinity Should Serve the Revelation of the Trinity in Scripture.

Leland Ryken’s Christian Guides to the Classics

The Crossway Christian Guides to the Classics series:

In these short guidebooks, popular professor, author, and literary expert Leland Ryken takes you through some of the greatest literature in history while answering your questions along the way.

Each book:

Includes an introduction to the author and work

Explains the cultural context

Incorporates published criticism

Defines key literary terms

Contains discussion questions at the end of each unit of the text

Lists resources for further study

Evaluates the classic text from a Christian worldview

Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress

This volume leads readers through John Bunyan’s classic Christian allegory, The Pilgrim’s Progress, offering insights into the nature of faith, the reality of temptation, and the glory of salvation.

Dickens’s Great Expectations

In this volume, Ryken guides readers through Dickens’s quintessential coming-of-age novel, Great Expectations. Exploring perennial themes such as love, justice, and heroism, this book stands as the preeminent example of Dickens’s unrivaled ability to conjure realistic characters and palpable settings.

Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter

This guide opens up the signature book of American literature, Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter, and unpacks its universal themes of sin, guilt, and redemption.

Homer’s The Odyssey

This guide opens up Homer’s The Odyssey and highlights the universal themes of endurance and longing for rest as displayed in this epic tale of a man trying to find his way home.

Milton’s Paradise Lost

This guide opens up the paramount epic in the English language, Milton’s Paradise Lost, and showcases Milton’s understanding of crime and punishment in the events of creation, paradisal perfection, the fall, and redemption.

Shakespeare’s MacBeth

This guide opens up the last of Shakespeare’s magnificent tragedies, Macbeth, and explores the themes of temptation, sin, and guilt, as well as the keys to virtuous behavior.

The Devotional Poetry of Donne, Herbert, and Milton (forthcoming in August 2014)

This particular volume will help readers understand and engage with the devotional poetry of three seventeenth-century poetic geniuses—John Donne, George Herbert, and John Milton.

Shakespeare’s Hamlet

(forthcoming in August 2014)

This volume will help readers understand and engage with William Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy: Hamlet.

June 17, 2014

Classic Literary Works to Challenge the Thinking Christian

Literature is one of the most effective—and enjoyable—ways to engage the culture.

Reading great literary works allows us to “test all things” (1 Thess. 5:21). Even reading works reflecting mindsets that deviate from a biblical worldview can spur on spiritual growth, allowing us to imitate Daniel and Paul who were learned in their surrounding pagan cultures and used that knowledge to point to the Creator of the universe. Furthermore, reading works that convey worlds of experience different from our own allows us to walk a mile in our neighbor’s shoes, thereby assisting us in loving them better.

Toward these ends—as well as for the sheer pleasure of reading a good book—I’ve chosen a short list, ranging from classics written centuries ago to works from more recent years, all of which offer (in addition to a rich literary experience) various kinds of challenges to most contemporary Christians. Sometimes the challenge is in disturbing material or notions that counter the comfort of commonplace ideas and experiences. Some of the works offer a direct challenge against Christianity or the church. Sometimes the challenging aspect is simply in the work’s level of reading difficulty.

But I’ve chosen all the works because I believe the returns offered by their challenges are well worth the reader’s investment. These works—presented in no particular order—are among my own personal favorites and by no means reflect any comprehensive or universal list of great books. I simply believe that these are works that offer edifying reading for the Christian who is willing to be challenged and stretched in a variety of ways. I would consider all of these works to be most suitable for mature readers.

Each work here has helped me, in one way or another, to love the Lord my God with all my soul, all my strength, and all my mind—and to be a better steward of this world in which God has placed us. I pray they do the same for you.

You can read her list, with explanations, here.

Perhaps for the rest of the week I’ll do some post on other works of literature highly recommended by Christian literary scholars and thinkers. Stay tuned.

There Is No Book Like the Bible

John Piper exults over God’s revelation to us in his Word, and explains why he is excited about Desiring God’s new venture in teaching the Bible online:

June 13, 2014

World Magazine’s Book of the Year in Popular Theology

John Frame calls it “the most creative apologetic book in many years” and Michael Kruger says is is simply “one of the best apologetics books in years.” Now World Magazine has named James Anderson’s What’s Your Worldview? their book of the year in the category of popular theology.

John Frame calls it “the most creative apologetic book in many years” and Michael Kruger says is is simply “one of the best apologetics books in years.” Now World Magazine has named James Anderson’s What’s Your Worldview? their book of the year in the category of popular theology.

Marvin Olasky writes:

THE ORIGINALITY and conciseness of James Anderson’s What’s Your Worldview? An Interactive Approach to Life’s Big Questions (Crossway) make it our Book of the Year in this category. Structured like a “Choose Your Own Adventure” interactive story, the outcome depends on the choices readers make. What’s Your Worldview? should appeal especially to teens and college students.

For example, answering yes to a question about the existence of objective truth takes the reader to the Knowledge question: “Is it possible to know the truth?” A yes answer there leads to the Goodness question: “Is anything objectively good or bad?” That yes answer leads to the Religion question, “Is there more than one valid religion?” A no answer leads to “Is there a God?” followed by “Is God a personal being?” and “Is God a perfect being?” Answering yes to both leads to questions about God communicating with humans, then to questions about Jesus, and eventually to Christianity.

Other answers start the reader down paths to many other worldviews, including atheistic dualism or idealism, deism or finite godism, Islam or Judaism, materialism or monism, mysticism or nihilism, pantheism or polytheism, relativism or skepticism, Platonism or Unitarianism, and so forth—21 options in all. When readers hit the end of the trail they have chances to think again: For example, those whose answers bring them to deism may reconsider the Communication question by going to page 34, the Perfection question by going to page 32, or the Personality question by going to page 29.

Some “Choose Your Own Adventure” storylines do not end happily—choose poorly and belligerent goblins await. What’s Your Worldview? demonstrates that most endings are self-contradictory or hard to live with. For example, Anderson asks readers who end up at pantheism, “Are you willing to say that ultimately everything is good and nothing is evil? Perhaps you are. But can you walk the talk as well? Can you live consistently with that result of your worldview?”

You can read the runners-up in this category as well as their other selections here.

June 11, 2014

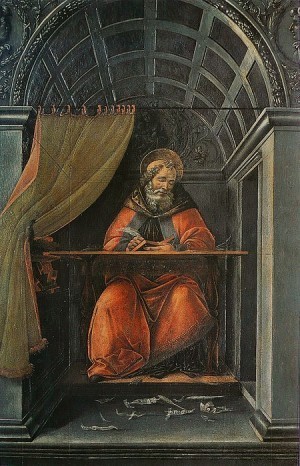

Should Augustine’s Name Be Pronounced *AW*-gus-teen or aw-*GUS*-tin?

David Horner, professor of biblical and theological studies at Biola University, seeks to answer the age-old dispute:

David Horner, professor of biblical and theological studies at Biola University, seeks to answer the age-old dispute:

[W]hile consideration of the Latin original of Augustine’s name does not determine a single, grammatically obligatory English pronunciation, it does suggest that aw-GUS-tin is the more fitting or appropriate pronunciation. This is because the latter most closely preserves the distinctive placement of the accent in the original. As we have seen, Augustine’s Latin name is properly pronounced ow-goost-EE-nus, with the accent on the penultimate syllable. The pronunciation of aw-GUS-tin preserves that accent pattern: when the final syllable is dropped from the Latin name in forming the anglicized name, aw-GUS-tin retains the accent on the penult rather than wrenchingly shifting it to the antepenult, as in the case of AW-gus-teen. In this way aw-GUS-tin is closer to the original pronunciation pattern, and it thus constitutes a more natural and appropriate pronunciation. For this reason, the Oxford Encyclopedic English Dictionary, recognized universally as authoritative in things most fine and fitting, lists aw-GUS-tin as the single recommended pronunciation.

You can read the whole thing here, humorously written in the style of a medieval disputation in response to a piece in a similar vein written by his colleague Garry DeWeese.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers