Bob Batchelor's Blog, page 11

August 21, 2019

The Bourbon King, The Inside Story: Why Write about George Remus

How did you discover the story of George Remus, and why did you decide to write a book about him?Imagine having a topic in your head for 17 years!I stumbled across George Remus about 17 years ago when Stanley Cutler, an esteemed American historian and scholar, asked me to write about bootlegging for the Dictionary of American History . Remus’s story was so epic that I couldn’t get it out of my mind. The “Bootlegging” entry had to be concise, so I didn’t get much of an opportunity to expand on the Remus story, but I snuck him in, as well as mentions of Cleveland and Pittsburgh.Here’s that bit from the essay:

Although researched and written so long ago, I still see bits of my personal writing style that persists. “Pervasive lawlessness” is a stylistic point, as well as the pacing of the sentence. Later, in 2013, I published a biography of The Great Gatsby , which I had been researching and writing for years. Obviously, the work on the book forced me to continue thinking about this crazy bootleg king, particularly since so many people began writing that he was the inspiration for Jay Gatsby, rather than just one of several.Given the pervasive lawlessness during Prohibition, bootlegging was omnipresent. The operations varied in size, from an intricate network of bootlegging middlemen and local suppliers, right up to America's bootlegging king, George Remus, who operated from Cincinnati, lived a lavish lifestyle, and amassed a $5 million fortune. To escape prosecution, men like Remus used bribery, heavily armed guards, and medicinal licenses to circumvent the law. More ruthless gangsters, such as Capone, did not stop at crime, intimidation, and murder.

— “Bootlegging” Dictionary of American History, 2003

[Spoiler alert: the link between Jay Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and George Remus is an important discussion in The Bourbon King and the beginning of one of America’s great literary mysteries that readers will really enjoy.]The more I thought about the bootleg king, the more it seemed that no one had really fully captured Remus or put him within the context of American history. His epic tale illuminates and interrogates the early twentieth century, Prohibition, Constitutionality, and many other topics that continue to confound people today. George Remus also fit neatly into my cultural historian and biographer wheelhouse: big topic, historically significant, and interesting links from that era to what we are experiencing today. I found that there were still many undiscovered aspects to Remus’s story and there were untapped archives, so I barreled ahead.

July 10, 2019

Starred Review in Publishers Weekly!

The Bourbon King: The Life and Crimes of George Remus, Prohibition’s Evil Genius received a starred review in Publishers Weekly, one of the essential publications in the publishing industry.

Larger-than-life characters take the reins of this story, a rip-roaring good time for any American history buff or true-crime fan.

Batchelor’s action-packed narrative both entertains and informs with its tales of the corruption of President Warren G. Harding’s attorney general, the bootlegging trade, and the public’s oscillating views of Remus and Prohibition in general.

You can find the complete review at this link!

February 21, 2019

George Remus, King of the Bootleggers: Insanity and Murder

Atlanta Constitution, February 22, 1928

A single shot…a fatal “gutwound”…murder in coldblood…

George Remus, the “King of the Bootleggers,” killed his wife Imogene on October 6, 1927, in Cincinnati’s Eden Park. The Queen City became the stage for one of the most sensational and media-saturated trials of the Jazz Age. Proving himself worthy as the evil genius of the Roaring Twenties, George devised a strategy to outwit the jury, convincing them that he had done society a favor by killing his wife. Remus claimed that she had wrecked his home, not only stealing his fortune, but taking on a lover.

At the time viewed as more a folk hero than confessed murderer, Remus and his co-counsel, the legal wunderkind Charles Elston, convinced the jurors that George had been insane when he pulled the trigger, driven mad by Imogene’s duplicity. “Temporary maniacal insanity,” was what Remus called it.

While George’s life would be spared, the state of Ohio would not let him go free. He was committed to the Lima State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, where he would — ironically — battle the courts to prove that he was no longer insane and not a threat to society. On February 21, 1928, he and Elston had Dr. P. I. Tussing testify that George was sane. The alienist even went so far as to assert that the murder was “what a large percent of normal persons would do under similar circumstances.”

The wrangling would continue…insane for an instant…sane ever after… The saga of George Remus and his fight for freedom would continue.

Read more in Bob Batchelor’s The Bourbon King: The Life and Crimes of George Remus, Prohibition’s Evil Genius, coming soon from Diversion Books.

November 13, 2018

Stan Lee: A Life Well-Lived -- Excelsior!

At the conclusion of Captain America: Civil War (2016), a FedEx delivery driver appears at the Stark Enterprises headquarters of the Avengers. Knocking on the glass, he asks, “Are you Tony Stank?”

James “Rhodey” Rhodes, Tony Stark’s best friend, points to his buddy, and exclaims: “Yes, this is Tony Stank…You’re in the right place. Thank you for that!”

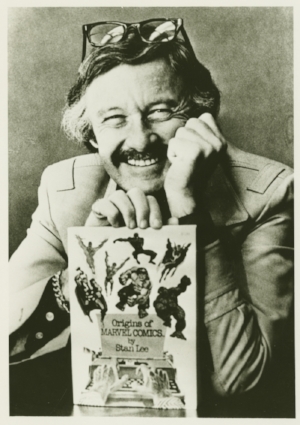

Stan Lee holding Origins of Marvel Comics

The FedEx employee is played by Stan Lee, his 29th cameo in superhero films. The scene ends the movie on a humorous note and, more importantly, demonstrates Lee’s place in the Marvel Universe. The package contains a letter from Captain America to Iron Man, turning over leadership of the Avengers to him, but also letting Stark know that he will still show up if the Earth faces peril. Lee’s cameo may seem a throwaway, but the moment is central to the plot, and points to how the Marvel Universe unfolds in the future. As Rhodes explains, Lee’s character is definitely “in the right place” – at the center of the action.

The cheerful conversation between Stark and Rhodes counterbalances the previous scene in which Rhodey – veteran military hero and War Machine combatant – struggles to walk again after breaking his back in the earlier superhero melee. Despite the dramatic edge, the tone and voice sounds as if Lee wrote the exchange in the early 1960s. Rhodes and Stark trade smirks and jokes, with Rhodes laughing, “Please, table for one for Mr. Stank, preferably by the bathroom.” The dialogue is a Lee line, set during a Lee cameo, in Lee’s Marvel Universe – his personality imprinted on a grand scale. Lee certainly fulfilled Martin Goodman’s early directive – create a bunch of superheroes. No one realized that the order would transform storytelling and American popular culture.

When Stanley Lieber became Stan Lee, he was hiding his real identity behind a pseudonym that he thought protected him from the disdainful scorn of those who looked down on the meaningless work he did in a trivial industry. Lee explained, “Early in my career, before The Fantastic Four, I struggled. I felt I was never going to get anywhere. Even afterward, I was embarrassed to say I wrote comic books for a living. I had a lot of shame about that.”[1] He carried that concept – the notion that what he did each day didn’t really matter – for decades.

Then, rising from his own anguish (and with goading from wife Joanie), Lee took ownership of who he was and what he might create if he changed his outlook and wrote what he wanted. Then, he turned the ideas over to some of the greatest artists to ever work in comics to create them visually. The Fantastic Four came to life…he birthed The Hulk…and soon Thor dropped down from the heavens. Countless additional characters endowed with otherworldly powers and unfathomable evil joined the early superheroes. Most significantly, Lee created the least likely hero around: a geeky teenager with a boatload of personal problems and whose life changes when a supercharged spider bites him. The Amazing Spider-Man was born.

The Marvel Universe did not begin with Spider-Man, but he was the one fans gravitated to the most – as did Lee. For Lee,

Spider-Man is more than a comic-strip hero. He’s a state of mind. He symbolizes the secret dreams, fears, and frustrations that haunt us all. We all have our hidden daydreams, daydreams in which we’re stronger, swifter, and braver than we really are – than we can ever hope to be. But, to Spider-Man, such dreams are reality.”[2]

Spider-Man sparked a revolution in comic books and storytelling by giving readers a fresh way of viewing superheroes. Finally, they seemed real, with feet of clay, just like people everywhere. Marvel’s characters possessed emotional weaknesses. They had to deal with their human emotions, not simply like Superman’s vulnerability, which came from magic rocks from a destroyed planet that bad guys stumbled over. In the final frame of his debut in Amazing Fantasy #15, Lee wrote the famous line that Spider-Man becomes: “Aware at last that in this world, with great power there must also come – great responsibility!” The way Spider-Man has since been popularized and immortalized across American culture, this line alone might have forever cemented Lee as an iconic writer.

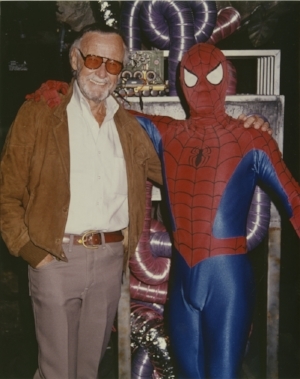

Stan Lee standing with Spider-Man (1994)

In short order, Lee created an interlocked network of superheroes and supporting characters that reflected the way people with extraordinary powers might actually live in the real world. Long before people could look back and realize Lee’s influence on the broader culture, they had to read the comic books. The genius he brought to the business, which launched the Marvel Age, centered on the way the characters spoke, their feelings, and the convincing issues they faced. The equation seemed almost too simple: if superheroes can be like you, then you can be like a superhero. Readers responded to Lee’s ideas and his authorial imprint developed into a central facet of popular culture.

Co-creating the characters and writing the stories with Marvel’s gifted artists, inkers, letterers, and colorists, however, did not end the process or Lee’s influence. He served other critical functions at Marvel that expanded his role far beyond the creative staff he worked with, including editing the comics, approving the artwork, and keeping the full-time staff and freelancers on task to meet the deadlines the publishing industry demanded. Then, realizing that his duties did not end there, he stumbled into serving as a mouthpiece for Marvel, first in the press, and then barnstorming the nation’s (and later the world’s) college campuses and public stages. The superhero stories went global and Lee told them again and again to whoever would listen.

On many occasions, Lee wondered when the superhero craze would wear off and he’d be onto another genre, fully expecting the boom-and-bust cycle to continue. From this perspective, the creative aspects of the job were tightly wound to the financial. “If Spider-Man hadn’t sold, we’d have forgotten about it,” Lee said. “To us they were just scripts. We were making them up, and we’d hope they’d sell, and some sold better than others, so those we kept.”[3]

There is no shortage of controversy or crisis in the entertainment industry. Often it seems as if these forces – not talent or success – fuel popular culture. Lee has faced various levels of condemnation for decades. To his critics, many of Lee’s actions have seemed inauthentic, centered on his own fame at the expense of others who should have been included in the spotlight’s glow. Even now, some antagonists have found his recent work focused mainly on making him money, not creating anything of lasting value. And, as well, the sides are tightly drawn in the pro-Kirby and pro-Ditko camps regarding who actually created the Marvel Universe.

Despite the challenges Marvel faced as an organization, the answer often came back to Spider-Man. The character’s enduring popularity saved the day. Lee’s willingness to keep the superhero top-of-mind ensured that Marvel also stayed securely on the nation’s popular culture radar. In turn, the effort solidified Lee’s own place in the cultural pantheon.

While people often credit Lee for his role in gradually turning comic books into a more respected medium and establishing Marvel’s place among the world’s great brands, he is rarely given enough credit simply as a writer. Just like novelist and filmmakers had always done, it is as if Lee put his hands up into the air and pulled down fistfuls of the national zeitgeist. As a writer, Lee did what all iconic creative people do – he improved on or perfected his craft, thus creating an entirely new style that would have broad impact across the rest of the industry, and then around the globe.

At the time Spider-Man appeared, Lee had already been working in the industry for more than 20 years. By this point, his writing process grew out his fascination with dialogue. He explained, “Whenever I write a story of any sort, I usually recite all the dialogue aloud as I’m writing it…I act it out, with all the emotion and corny emphasis that I can must.” What this kind of writing and narration forces is what all great writers understand: “It’s got to sound natural.”[4] These innovations – focusing on realistic dialogue, speaking directly to the reader, and allowing the reader into the character’s thinking via thought bubbles – created the Marvel style that would soon dominate the comic book industry and then gradually extend to film, television, literature, and other forms of storytelling.

Generations of artists, writers, actors, and other creative types have been inspired, moved, or encouraged by the universe Lee voiced and birthed. While he did not invent the imperfect hero (one could argue that such heroes had been around since Homer’s time and even before), Lee delivered the message to a generation of readers hungry for something new. The nerd-to-hero storyline seems like it must have sprung from the earth fully formed, Lee gave readers a new way of looking at what it meant to be a hero and spun the notion of who might be heroic in a way that spoke to the rapidly expanding number of comic book buyers. Spider-Man’s popularity revealed the attraction to the idea of a tainted hero, but at the same time, the character hit the newsstands at the perfect time, ranging from the growing Baby Boomer generation to the optimism of John F. Kennedy’s Camelot, this confluence of events resulting in a second golden age for comic books. Fans gobbled up his superheroes with their dimes, nickels, and quarters.

Regardless of the opinions of nay-sayers, there is something heroic in Lee himself. Like others at the apex of American popular culture, Lee transformed his industry, which then had much broader implications. Lee became Marvel madman, mouthpiece, and all-around maestro – the face of comic books for six decades. The man who wanted to pen the Great American Novel did so much more. Without question, Lee became one of the most important creative icons in contemporary American history.

Endnotes:

This essay is drawn from my 2017 book, Stan Lee: The Man Behind Marvel, published by Rowman & Littlefield

Images courtesy of Stan Lee Papers, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming

[1] Lee, interview by Hochman.

[2] Memo, Marvel Comics Group – Manuscript Information, 1974, Box 6, Folder 8, Stan Lee Papers, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

[3] Stan Lee, interview by Jeff McLaughlin, “An Afternoon with Stan Lee,” 2005, in Stan Lee Conversations, ed. Jeff McLaughlin (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2007), 211.

[4] Lee and Mair, 135.

September 15, 2017

5 Questions for Stan Lee Biographer and Cultural Historian Bob Batchelor

Stan Lee at the typewriter, circa 1950. Courtesy of Stan Lee Papers, Box 145, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming

Why did you feel that Stan Lee needed a full-scale biography?

Ironically, when I interviewed self-professed Marvel and Lee fans, what I realized is that most didn’t know much about him (and much of what they thought they knew wasn’t the whole story). From this research I realized that my best bet would be to write a biography deeply steeped in archival research that provided an objective portrait that would give readers insight and analysis into Lee’s life and career. The research provided a deeply nuanced view of Lee’s life that I then conveyed to the reader. This commitment to the research and uncovering the man behind the myth is the driving force in the book.

In looking at a person’s life, especially one as long as Lee’s (he’ll turn 95 at the end of the year), context and historical analysis provides the depth necessary to create a compelling picture. So, for example, Lee grew up during the Great Depression and his family struggled mightily. I saw strains of this experience at play throughout his life that I then emphasized and discussed. As a cultural historian, my career is built around analyzing context and nuance, so that drive to uncover a person’s life within their times is at the heart of the narrative.

What would people find most surprising about Stan Lee’s career?

What many people don’t know about Stan Lee’s career is that he was the heart and soul of Marvel the publishing company, not just a writer as we might think of it today, toiling away in solitude. In addition to decades of writing scripts for comic books across many genres, like cowboy stories, monster yarns, or teen romances, Lee served as Art Director, head editor, and editorial manager, while also keeping an eye on publication and production details. The totality of his many roles, including budgeting for freelance writers and artists, necessitated that he keep his freelancers active, while also engaging them differently than other comic book publishers.

Lee worked with his artists, like the incomparable Jack Kirby and wonderful Steve Ditko, to co-create and produce the characters we all know and love today. The process that Lee created out of necessity because he had to keep the company efficient and profitable came to be known as the “Marvel Method.” It gave the artists more freedom in creating stories, since traditionally they worked off a written script. The Marvel Method blurred the definition of “creator,” but when Lee, Ditko, and others were creating superheroes, no one thought that they would become such a central facet of contemporary American culture. The line in the sand between who did what has become important to comic book aficionados and historians, but back then, they were just trying to make a living. So, if we want to fully understand Stan Lee and Marvel’s Silver Age successes, then we have to look at his myriad responsibilities in total.

How does your biography add to our understanding of Stan Lee?

Popular culture is so much more prevalent in today’s culture almost to the point of chaos. People feel pop culture – for better or worse – much more, since it is always blasting away at us. We feel that we “know” celebrities like Lee, because we engage with them much more than ever before. For example, Lee has 2.71 million Twitter followers.

Given that Lee is a mythic figure to many Marvel fans, I think what I’ve done well in the biography is present a full portrait of Lee as a publishing professional, film and television executive, cultural icon, and family man. One gets the sense of Lee as all these things when examining his archive at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Lee is so much more than the much-anticipated film cameos and the biography attempts to reveal his family background, sorrows, triumphs, and successes in a way that hasn’t been done before.

What keeps you writing?

Regardless of the topic, storytelling is my foundation. Trying to figure out what makes a fictional character like Don Draper or Jay Gatsby tick versus an actual person like Lee or Bob Dylan, I am putting the storytelling pieces together to drive toward a better understanding. Phillip Sipiora, who teaches at the University of South Florida, is famous for saying that there aren’t really definitive answers, rather that the goal of the critic should be interrogation and analysis. I am not searching for the right answer, rather hoping to add to the body of knowledge by looking at a topic in a new or innovative way.

Throughout the process, I reserve time to just think deeply about the subject. I find that meditative time is essential. The fact that most people can no longer stand quiet, reflective time is one of the great tragedies to emerge from the web. I create basic outlines to guide my writing and thinking and constantly edit and revise. When I coach writers, I urge them to find a process that works for them, and then to hone it over time. My process fuels my work and enables me to work efficiently.

You’ve written or edited 29 books, what’s next?

In the near term, I think I have some things to say about early twentieth century American literature and its significance. Many people think they know the story, but there are still ideas to uncover there that are important to us 100 years later. I am also interested in working more in both film and radio. I’ll never give up writing and editing, but I would like to pursue some documentary projects and possibly create a radio show or some other way to reach larger audiences. Despite our current political climate, I think people still yearn for smart content, and I would like to fill that need.

May 22, 2017

Stan Lee in World War II: The Signal Corps Training Film Division

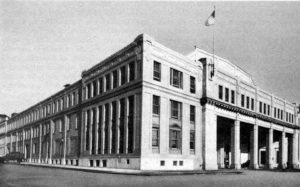

The Signal Corps Photographic Center -- Astoria, Long Island

After Stan Lee enlisted in November 1942, his basic training took place at Fort Monmouth, a large base in New Jersey that housed the Signal Corps. The Signal Corps played a significant military role. Research played a prominent role in the division and on the base. Several years earlier, researchers had developed radar there and the all-important handheld walkie-talkie. In the ensuing years, they would learn to bounce radio waves off the moon.[i]

At Fort Monmouth, Lee learned how to string communications lines and also repair them, which he thought would lead to active combat duty overseas. Army strategists realized that wars were often determined by infrastructure, so the Signal Corps played an important role in modern warfare keeping communications flowing. Even drawing in numerous talented, intelligent candidates, the Signal Corps could barely keep up with war demands, which led to additional training centers opening at Camp Crowder, Missouri, and on the West Coast at Camp Kohler, near Sacramento, California.

On base, Lee also performed the everyday tasks that all soldiers carried out, like patrolling the perimeter and watching for enemy ships or planes mounting a surprise attack during the cold New Jersey winter. Lee claimed that the frigid wind whipping off the Atlantic nearly froze him to the core.

The oceanfront duty ended, however, when Lee’s superior officers realized that he worked as a writer and comic book editor. They assigned him to the Training Film Division, coincidentally based in Astoria, Queens. He joined eight other artists, filmmakers, and writers to create a range of public relations pieces, propaganda tools, and information-sharing documents. His ability to write scripts earned him the transfer. Like countless military men, Lee played a supporting role. By mid-1943, the Corps’ consisted of 27,000 officers and 287,000 enlisted men, backed by another 50,000 civilians who worked alongside them.

The converted space that the Army purchased at 35th Avenue and 35th Street in Astoria housed the Signal Corps Photographic Center, the home of the official photographers and filmmakers to support the war effort. Col. Melvin E. Gillette commanded the unit, also his role at Fort Monmouth Film Production Laboratory before the Army bought the Queens facility in February 1942, some nine months before Lee enlisted. Under Gillette’s watchful eye, the old movie studio, originally built in 1919, underwent extensive renovation and updating, essentially having equipment that was the equivalent of any major film production company in Hollywood.

[image error]

Col. Melvin E. Gillette, the "architect of Military Pictorial Service"

Gillette and Army officials realized that the military needed unprecedented numbers of training films and aids to prepare recruits from all over the country and with varying education levels. There would also be highly-sensitive and classified material that required full Army control over the film process, from scripting through filming and then later in storage. The facility opened in May 1942 and quickly became an operational headquarters for the entire film and photography effort supporting the war.

The Photographic Center at Astoria, Long Island, was a large, imposing building from the outside. A line of grand columns protected its front entrance, flanked by rows of tall, narrow windows. Inside the Army built the largest soundstage on the East Coast, enabling the filmmakers to recreate or model just about any type of military setting.

Lee found an avenue into the small group of scribes. “I wrote training films, I wrote film scripts, I did posters, I wrote instructional manuals,” Lee recalled. “I was one of the great teachers of our time!”[ii] The illustrious division included many famous or soon-to-be-famous individuals, from three-time Academy-award winning director Frank Capra and New Yorker cartoonist Charles Addams to a children’s book writer and illustrator named Theodor Geisel. The world already knew Geisel by his famous penname “Dr. Seuss.”

Although Lee often jokes about his World War II service, even a passing examination of the work he and the other creative professionals performed for the nation reveals the significance of the division across multiple areas. According to the official history of the Signal Corps effort during World War II:

Even before Pearl Harbor the demand for training films was paralleling the growth of the armed forces. After war came the rate of demand rose faster than the rate of growth of the Army, because mass training of large numbers of men could be accomplished most effectively through the medium of films. For fiscal year 1942 the sum of $4,928,810 was appropriated for Army Pictorial Service, of which $1,784,894 was for motion picture production and $1,304,710 for motion picture distribution, chiefly of training films. More than four times that sum, $20,382,210, was appropriated for the next fiscal year, 1943, and half went for training films and for training of officer and enlisted personnel in photographic specialist courses.[iii]

The stories that must have floated around that room during downtime or breaks!

[i] During the time Lee was stationed at Fort Monmouth, Julius Rosenberg carried out a clandestine mission spying for Russia. He also recruited scientists and engineers from the base into the spy ring he led in New Jersey and funneled thousands of pages of top-secret documents to his Russian handlers. In 1953, Rosenberg and his wife Ethel were arrested, convicted, and executed.

[ii] Stan Lee, interview by Steven Mackenzie, “Stan Lee Interview: ‘The World Always Needs Heroes,’” The Big Issue, January 18, 2016, http://www.bigissue.com/features/inte....

[iii] Thompson, George Raynor, Dixie R. Harris, et al. The Signal Corps: The Test (December 1941 to July 1943). (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, 1957), 419.

May 18, 2017

The Black Knight Debuts in 1955

“Strike, black blade! The Black Knight challenges Modred the Evil!”

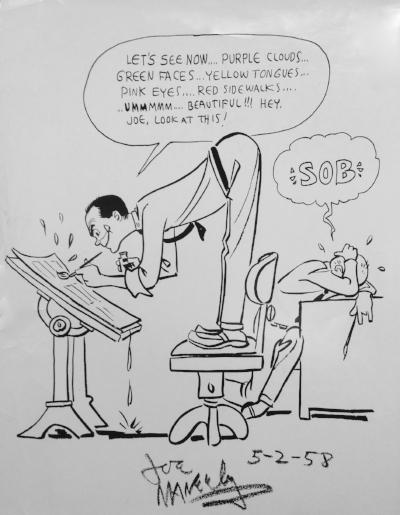

The Black Knight, created by Stan Lee and Joe Maneely for Marvel Comics (then known as Atlas Comics)

Mixing the legendary tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table with elements from superhero lore, Stan Lee and his favorite artist Joe Maneely cocreated The Black Knight for Atlas Comics, debuting in May 1955.

Lee and Maneely took a risk in bringing out the new hero, despite the enduring popularity of King Arthur for centuries. Superhero comic books were basically out of favor in the 1950s, thanks to the ravings of lunatic psychiatrist Frederic Wertham and countless adults who believed his diatribes against the industry, particularly that reading comic books paved the path to juvenile delinquency.

Wertham’s backlash had sent the publishing industry reeling, forcing many companies into bankruptcy. If you didn’t work at a publisher named DC or have characters like Superman and Batman, then turning to other genres proved the only way to stay afloat.

The artistic duo’s creation featured a powerful, armored hero who hid behind a secret identity (the meek Sir Percy of Scandia) so that he could thwart wrongdoers. The Black Knight worked with famed magician Merlin to protect and defend King Arthur's Camelot from the schemes of Modred the Evil.

In the post-Wertham environment, publisher Martin Goodman and editor Lee fiddled with the comic book lineup, attempting to find the right mix that readers would buy. At that time, however, superheroes were out at Atlas. Even the mighty Sub-Mariner would be cancelled in October 1955 with Sub-Mariner #45.

Despite how much the artistic duo of Lee and Maneely loved the Black Knight character, the series only lasted five issues, folding with the April 1956 cover dated copy. Instead, the company moved to cowboy comics, suspense series, and Hollywood tie-ins in an attempt to wrangle the fickle marketplace. Atlas' place on the newspaper stands would feature titles like World Of Fantasy, World of Mystery, and old favorites like Millie The Model.

May 15, 2017

University of Marvel Comics

Marvel University Diploma, 1993

A fun "diploma" uncovered in the Stan Lee Papers at The American Heritage Center (AHC) at the University of Wyoming. Countless young comic book readers would have loved to attend "Marvel University" and affix that college seal to their diplomas.

But, how would they ever decide who would be the school mascot?

The Marvel certificate is one of countless rarely seen treasures at The American Heritage Center (AHC), the unique library and archive at the University of Wyoming in the Western town of Laramie. AHC is the university’s repository of manuscript collections, rare books, and university archives. One of its many fine collections focuses on the Comic Book Industry.

The Stan Lee Papers comprises one of AHC's strongest collections (others include the papers of Private Snafu writer/editor Harold Elk Straubing and Superman editor Mort Weisinger). The Stan Lee collection is a seemingly endless archive of Lee’s work at Marvel, particularly valuable in the era from the 1940s to 1970s.

The Stan Lee Papers contain a wide range of documents and items, not just papers, though the archive has box after box of Lee’s business correspondence, fan mail, and Marvel internal memos.

May 11, 2017

Spider-Man (2002) Film Sets Box Office Record!

Stan Lee worked in Hollywood for decades in hopes of seeing a Spider-Man film to fruition. Yet, various misfires, failed scripts, and skepticism on the part of film executives derailed the work time and time again.

[image error]

Stan Lee posing with "Spider-Man" in 1994

Lee remained vigilant, believing that a well-crafted Spider-Man film would capture the hearts of moviegoers, just as it had comic book readers and people who snapped up the merchandise that featured the teen superhero. Spidey had starred in numerous animated series, in addition to the appearances on The Electric Company and in video games. Yet, despite the evidence of the character's enduring significance and popularity, Hollywood did not beat down Lee's door to make the film version.

Finally, under director Sam Raimi's watchful eye, Spider-Man started taking shape, which would star Tobey Maguire as the Web-Slinger and Kirsten Dunst as Mary Jane Watson. The film concentrated on the Spider-Man origin story and feature Willem Defoe as the Green Goblin, one of Spidey's most sinister foes.

After a comprehensive marketing campaign leading up to the film's release, Spider-Man set a box office record for a weekend opening, taking in about $115 million, besting Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, the previous number one at $90 million.

Lee, who appeared in the film as a bystander to a battle between Spider-Man and the Green Goblin in Times Square, had to feel vindicated after the tremendous financial success of the film, making about $820 million worldwide and at the time the most successful comic book movie ever made.

May 8, 2017

Stan's First Team-Up: Stan Lee and Artist Joe Maneely

Sketch of Stan Lee fiddling with artwork by Joe Maneely -- courtesy of Stan Lee Papers, Collection Number 8302, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming

History if full of "what if" moments.

Comic book history changed forever the early hours of June 7, 1958, when artist Joe Maneely fell between moving commuter railway cars on the way to his New Jersey home.

Maneely and Stan Lee were close friends and artistic teammates at Atlas Comics, the name publisher Martin Goodman used during the 1950s. Lee and Maneely had worked on a syndicated newspaper strip -- Mrs. Lyons' Cubs -- then as Lee's favorite artist to work with, Maneely penciled and inked countless comic book covers and issues. The two shared a common sensibility and manic energy.

The drawing from May 1958, just a little more than a month before the artist's untimely death, captures Lee's spirit and Maneely's reaction to "purple clouds" and "red sidewalks."

The "what if" question for Lee and Maneely would have centered on what role the eminent artist would have had on the superhero genre and Lee's trajectory if he had lived. In interviews, Lee has mentioned that he and Maneely may have gone into partnership and left Goodman's operation.

If Maneely would have survived, perhaps Lee feels less inclined to turn to Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko when the superhero craze caught fire. Maneely's recollection of working with Lee in the 1950s would also provide comic book historians and aficionados insight into the writer/editor's work habits, scripts, and other topics during the extreme challenges the comic book industry faced in the 1950s.

The Maneely sketch is one of many rarely seen treasures at The American Heritage Center (AHC), the unique library and archive at the University of Wyoming in the Western town of Laramie. AHC is the university’s repository of manuscript collections, rare books, and university archives. One of its many fine collections focuses on the Comic Book Industry.

The Comic Book Industry collection is “unique in documenting the editors and writers of this industry increasingly recognized by scholars as having significant impact on the nation’s popular culture.”

One of the most noteworthy collections at AHC is the Stan Lee Papers (others include Private Snafu writer/editor Harold Elk Straubing and Superman editor Mort Weisinger). The Stan Lee collection is a seemingly endless archive of Lee’s work at Marvel, particularly strong in the era from the 1940s to 1970s.

The Stan Lee Papers contain a wide range of documents and items, not just papers, though the archive has box after box of Lee’s business correspondence, fan mail, and Marvel internal memos.