Xianna Michaels's Blog, page 6

June 16, 2016

San Francisco Book Review calls Lily “A Beautiful Tribute.”

This heartfelt saga in verse form is about five generations of women’s journeys from Russia’s persecuting pogroms of the 1890s to America during the 2000s, including Ellis Island and New York’s Lower East Side sweatshops.

The story is broken up into five parts, one for each of the women’s generation. The story begins and ends with Lily. Laili is a young girl who flees Russia during the pogrom of 1890’s that persecuted Jews. Her name changed to Lily on Ellis Island. Part Two tells the tale of Lily’s daughter, Molly, who unlike her mother, survives the fire in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. Molly’s daughter, Lily, grows up during the Great Depression of the 1930s, but fortune smiles on her and she marries and has a daughter, Maxine whose tale about growing up in the 60s is told in Part Four. Maxine’s daughter Lily reaps the benefit of modern day America. But she acknowledges that her good fortune came about because of all the sacrifice and perseverance of the spirited women before her who had dreams of a better life—free of discrimination and persecution for being Jewish.

Author Xianna Michaels wastes no time diving into the theme of persecution and hope, with the first stanza explaining how the pogrom, and the attack on her mother and infant brother led to Lily and her sister, Basya, being sent on a ship, To the Goldene Medina, where life/Is free of fear and blood and strife. Michaels effectively gets to the crux of each story, maintaining the fast flow as all five generations of women trying to find their new identity while maintaining and learning about their Jewish heritage. Michaels reveals how life improves for each generation by infusing details that are also historical milestones—such as the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire that kills Molly’s mother and the mention of the G.I. Bill.

While the ababcc rhythm limits the narrative at times for the sake of rhyming, it works well at times to create a juxtaposition of light rhyme and heavy content during some of the heavier descriptions—including in the last two lines of the stanza: It was ninety two, the end had come/For this was Laili’s last pogrom. Though some of the descriptions to accommodate the rhyming scheme are simplified and don’t expound on the themes and details as much as they could; it makes this story suitable for a younger audience, and can be a spring board into rich discussion on themes about numerous events in history including Jewish immigrants in America and how they influence in New York’s culture.

Lily of The Valley—An American Jewish Journey is a beautiful tribute, not only to America—a land of opportunity and hope—but also to family, love and human spirit.

Read the full review here at San Francisco Book Review.

The post San Francisco Book Review calls Lily “A Beautiful Tribute.” appeared first on Xianna Michaels.

May 11, 2016

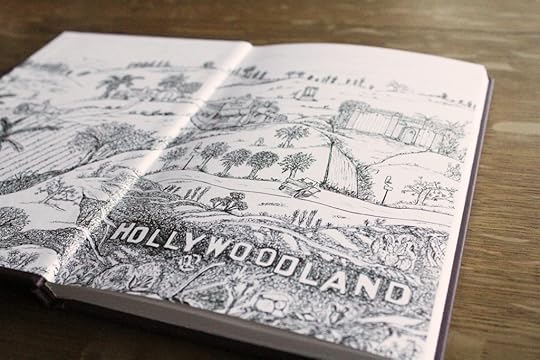

History, Symbol and Whimsy: The Story Behind the Artwork of Lily of the Valley

One of the great joys for me in creating my new book, Lily of the Valley—An American Jewish Journey, was doing the artwork. This allowed me to explore my love of history—particularly as it pertains to the gradual changes in everyday life—and the symbolism that Lily holds for me, as well as to indulge a bit of whimsy.

This book is the story of five generations of American Jewish women, and each of the five parts begins with a border vignette depicting the time in which that particular character lived. The vignettes are meant to enhance the story, set a mood, and draw the reader in, somewhat in the way that a film score does for a movie. In addition it is my hope that the drawings provide a certain delight for the eye. Books for adults are not illustrated the way children’s books are, and yet I think we never really outgrow our enjoyment of the visual.

And so the border for “Part I— Lily” shows the Statue of Liberty with the approaching ship, then a scene from the Lower East Side at the beginning of the 20th Century. “Part II—Molly” depicts the era from World War I through the 20’s, including the soldier, the trolley and the lady in the cloche hat. In “Part III—Lily” fashion has changed dramatically, and there’s a car in front of the suburban home. I drew the World War II soldier from a picture of my father, of blessed memory, in his uniform. “Part IV—Maxine” is the age of flower power, as well as the beginning of the return to observant Judaism for Maxine and many others, and “Part V—Lily” depicts modern day Los Angeles.

The vignettes at the bottom of each border give rise to all manner of lilies, including lilies of the valley. In the border for Part I the symbolism is clear, as the flame of hope in the torch of the Statue of Liberty, as well as the flames of the tragic factory fire, transform into the leaves and flowers. And the early borders hint at palm trees, a nod to one of the first Lily’s dreams. By the end the Southern California foliage shows the dream come to fruition.

The front book cover came from a vision I had of the title rising from the flower of its name in full bloom, and the back cover in a way symbolically tells the whole story. It begins with flames—a pogrom, a factory fire. The flames transform into flowers, to lilies, as Lily’s dreams take hold, and then on the top the palm leaves come together, as do all the aspects of the first Lily’s dreams for her family. I loved creating that back cover!

I also enjoyed doing the decorative initials that begin each part of the book. They harken back to medieval manuscripts, when almost all stories were told as poems. But they also are meant to be evocative of the passage of time. The sewing machine in Part I was cutting edge technology at the turn of the 20th Century, and the flames foreshadow tragedy to come. The candlestick phone and radio in Part II are more of the latest technology, as is the television in Part III. Part IV brings the psychedelic Sixties, and Part V evokes the 21st Century, complete with iPhone, high heels in the workplace, and a nod to the Twin Towers. I fully enjoyed doing these initials. Besides the process of drawing, I felt like I was creating stories within the larger story.

Finally, I indulged a bit of whimsy with the endpapers. As with all hard covered books, these are the folded sheets with one half glued to the inside of the front cover and the other forming the first free page of the book. The back endpapers do the same in reverse. I love to create scenes for my endpapers. Lily of the Valley shows a melange of images from the old-time San Fernando Valley, including a horse and cart, an old adobe house and a general store. Then there is the roadway lined with bell markers identifying El Camino Real, the original trail of Spanish missions. That eventually became the 101 Freeway and today is known as Ventura Boulevard, the longest contiguous stretch of businesses in the world. And then there’s the house with the gate nestled somewhere above the Hollywoodland sign. Perhaps some of my readers might recognize it!

There is a special magic for me in transferring a vision I have in my mind onto the page with pen and ink. This is especially true because, while I have been writing poems and stories all of my life, I did not begin drawing until I was in my 40’s. That’s a story in itself, but suffice it to say that discovering I could draw was a surprise that continues to be a source of delight for me. I hope I have communicated some of that delight to the readers of Lily of the Valley. One of the great joys for me in creating my new book, Lily of the Valley—An American Jewish Journey, was doing the artwork. This allowed me to explore my love of history—particularly as it pertains to the gradual changes in everyday life—and the symbolism that Lily holds for me, as well as to indulge a bit of whimsy.

The post History, Symbol and Whimsy: The Story Behind the Artwork of Lily of the Valley appeared first on Xianna Michaels.

May 1, 2016

What I’m Thinking About This Mother’s Day

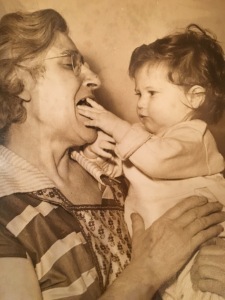

Here I am at 7 months old with my grandmother.

As Mother’s Day approaches, I’m thinking about my new book, Lily of the Valley—An American Jewish Journey, just published in March. It’s about five generations of women pursuing the American Dream and what happens to their connection to observant Judaism as they do so. The book is dedicated in memory of my father and in honor of my mother, both children of Ellis Island immigrants who imparted their faith in the American Dream to me.

This book is not autobiographical, but there are certainly parallels in my own family’s story. There was my paternal grandmother, who came here as a child and was put to work in a sweatshop at the age of nine. She would go on to have six children, and all of her grandchildren would go to college. There was my maternal grandmother, who survived a pogrom and literally kissed the ground at Ellis Island. She never tired of telling me, in her broken English and with a catch in her throat, how much she loved this country, how America had saved her. I remember all through my childhood watching her, bent over her kitchen table, braiding the golden cords that would decorate American military uniforms.

Then there is my mother, who sewed all my clothes when I was young, up to and including my wedding gown. She and my father didn’t keep the Sabbath—it simply wasn’t part of their upbringing—but they did keep a kosher house, and my mother always lit candles on Friday night. I was the Baby Boomer who came back to observant Judaism, with the confidence, shared by so many of my peers who did the same, that we could return to living a Torah life and still participate fully in the American Dream. My husband and I raised our children that way, as they are raising their’s. And as it happens one of my daughters is a dress designer and stylist, paralleling the dream of Lily’s family.

So this Mother’s Day as I think about Lily and her family, I’m also thinking about mine, and about how my grandmothers came over in steerage so we could live a life they could barely imagine, in this Golden Land we call America.

The post What I’m Thinking About This Mother’s Day appeared first on Xianna Michaels.

April 3, 2016

What do Thomas Jefferson, Oscar Hammerstein II and My High School Chemistry Class Have in Common?

So what do Thomas Jefferson, Oscar Hammerstein II and my high school chemistry class have in common? As it turns out, something rather significant, though it took me many years to figure it out. And it’s not just our third president and the lyricist half of the Rodgers and Hammerstein team that brought us such great classic musicals as Oklahoma and South Pacific—we can add Emily Dickinson, Benjamin Franklin, Lewis Carroll and a host of other luminaries into the mix.

What on earth am I talking about? I’m talking about desks, standing desks to be precise. You see, all of these extremely talented people worked at desks that were of a height that required them to stand as they wrote. Not all great writers do so, of course, but quite a few did and do. Is there a reason for this, or is it just another one of those inexplicable idiosyncrasies of the creative process? And then there are those who do sit at a desk to work but report frequently getting up to pace, stretch or even go out to retrieve the mail. Are they merely procrastinating? Why is it that if I am at a loss for the next line of poetry or the transition to my next paragraph, I instinctively get up from my desk? I may take a short walk outside, get a glass of water or replace a book on the bookshelf. Is this procrastination? Mere distraction? And if distraction is the motivation, why is it that invariably when I return to my desk, the precise words that I needed just happen to spill out of my pen?

When I was in high school and had an essay to write, I would forego the desk in my room as well as the kitchen table and retreat to our finished basement. And there I would pace around in circles, stopping to write down sentences as they came to me. I thought this a little strange on my part, and was very glad to be holed up where no one else could bear witness. I could do other kinds of homework upstairs, but I instinctively found that stories and essays seemed to flow when I could walk my endless circles. I’m no Oscar Hammerstein II, but decades later when I read that he used to pace his courtyard in circles as he composed his immortal lyrics, I was fascinated. He also, of course, used a standup desk. What was going on here?

I have long found that new stories start coming to me on my morning walk, as do stanzas of poetry, one after another, so that sometimes I find myself cutting the walk short to head home and record it all. My new book, Lily of the Valley—An American Jewish Journey, first began coming to me in snippets of rhymed poetry, day after day, on my walk.

What does any of this have to do with my high school chemistry class? Ah, well, I’m getting there. There has been a great deal of talk in recent years about the deleterious health effects of the basically sedentary lifestyle of the industrialized world. The idea of treadmill desks to combat obesity, heart disease and the like has been gaining traction for years. Then researchers started saying that walking promotes new connections between the brain cells. It makes the heart pump faster, circulating more blood and bringing more oxygen to the brain. There is plenty of anecdotal evidence of people claiming to think better on their feet, or that they do their best thinking while walking. The late Steve Jobs was famous for holding important business meetings on long walks, and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg has also held walking meetings. The writer, poet, philosopher and great walker Henry David Thoreau wrote in his journal in 1851: “Methinks that the moment my legs begin to move, my thoughts begin to flow.”

But apparently it’s not just walking; even standing has an impact on creativity. New studies have been revealing that standing desks—no treadmill in sight—can benefit not just heart health but brain health. There is growing evidence that standing itself increases blood flow to the brain, improves the ability to focus, and may stimulate neural connectivity. In other words, standing versus sitting may allow the brain cells to connect in new ways, to let new ideas come to us, to let the words flow in ways they wouldn’t otherwise. That is because when we stand, we are not perfectly still. Our feet shift. Our legs move, however slightly, however unconsciously. And as the body moves, so the brain seems to move if you will, to open to new possibilities.

I do not pretend to understand the brain chemistry, and I’m sure I’m not unique among writers to have discovered the benefits of movement for our creative process, whether it be conscious or not. The scientific studies now coming out are a gratifying corroboration of what we instinctively know. And if these studies lead to greater creativity and productivity in the workplace, then that is a fine thing. But my hope is that one day this will filter into the classroom, and our understanding of the way students learn. Which brings me, finally, to high school chemistry.

A little background is in order. I was one of those students who was considered “good” in English and history, and I enjoyed those subjects immensely. But I was not at all good in math and science, and not surprisingly, I disliked those subjects immensely. Algebra, geometry, trigonometry, et al were a form of torture to me. They were completely opaque and incomprehensible, and I twisted myself into knots trying to succeed in those classes. Not to mention that I was bored to tears. The same could be said for physics. Anything to do with numbers was my nemesis. Biology, which involved a great deal of reading and writing, wasn’t all that bad (other than the dissections, which made me ill.)

The odd exception to all of the above was chemistry. It certainly involved numbers, formulas, equations—plenty of math—and yet I rather enjoyed it. I understood it and did well in it without torturing myself. And I never knew why. Why was it that I “got” chemistry while all other such subjects were impossible for me? It wasn’t about the teacher. While I did have an excellent high school chemistry teacher, I was blessed to have gone to schools with excellent teachers all around. I knew, even at the time, that my math and science teachers were good. They really tried to help me and were as frustrated by my inability to “get” what they were teaching as I was. So what was different about chemistry?

The answer hit me only recently, like the proverbial ton of bricks, when I was reading about standing desks and the brain. You see, in school I sat at the same desks most students sit at—small desks with chairs that barely fit underneath, that allow for little movement. And sometimes we had those combination desk-chairs, one attached to the other with no movement possible at all. But in chemistry we had lab tables. High lab tables. And we had high stools on which we were meant to perch as we listened in class. I didn’t like those stools. I am five feet tall and it felt like too much of a climb to get onto them, and the swivel made me dizzy. The lab tables came up to my chest and I found it comfortable to stand. No one, including the teacher, paid much attention as I wasn’t high up and disrupting anything. I simply stood with my notebook in front of me at a comfortable height, listened and took notes. And I “got it.” No one noticed, but apparently my brain did. My brain opened, or formed connections, and allowed me to learn in a way that I could not in other math and science classes. All because of the lab table! I was able to stand, and my brain was somehow able to do chemical equations!

And so today, many years later, as I stand or walk around as needed while I write, I think about kids in school. And I cannot help but wonder how many of them sit, their young brains as confined as their legs, in furniture that may stifle their ability to learn. How many essays could be better written if students had the option of standing while writing? How many more students might pursue career paths in math or science if they could stand while in class? How many more insightful analyses and answers to questions might they generate? How many more young people might consider themselves creative?

Perhaps Thomas Jefferson, Emily Dickinson and others like them have a lot more to teach us than we ever could have imagined!

The post What do Thomas Jefferson, Oscar Hammerstein II and My High School Chemistry Class Have in Common? appeared first on Xianna Michaels.

On Losing Shoes and Finding Joy

There’s an old Chinese saying that for every child you lose a tooth. Praise G-d, that has not been my experience! But I do have a saying of my own: that for every grandchild I lose a shoe. I do not mean that I become increasingly doddering and misplace my footwear, but rather that every time I am blessed to have a new grandchild it seems that there is another category of shoes that I can no longer wear.

Allow me to explain. I was told many years ago, because of lower back issues, not to wear high heels. Fair enough. So I spent most of my adult life wearing flats for everyday and the occasional short heels for dressy occasions. No problem. My feet were happy. I used to shop in a sample shoe shop that had rows and rows of shoes in small sizes, and I would find interesting, one-of-a-kind shoes at delightfully low prices. Things like apricot suede knee-high boots, burgundy velvet sparkly flats and shoes in my favorite forest green long after the color had gone out of vogue everywhere else. I’m fairly gentle with my shoes so most of them lived happily in my closet for a long time.

This meant that, organized as I try to be, eventually I began running out of space. I should also explain that I live in an old house, built long before people had the amount of “stuff” that seems essential today. Our closets are small. The master dressing area does have a cute little built-in shoe cabinet, which fits exactly twenty pairs of shoes. Does that sound like plenty? Then you must be a male person reading this. Trust me as a female, that is not plenty. So eventually I had shoes lined up on the closet floor and the shelf above. Now, I am not a shoe-aholic. But one does need the occasional new pair of shoes, and I rarely had reason to discard any, as they were in perfectly fine condition.

As it turned out, and much to my surprise, my feet were not. Was it the broken toe that started it? The twisted ankle? The spontaneous occurrence of an Achilles tendonitis that necessitated six months in a lovely black nylon velcroed boot? All I know is that as time went on—and I am not implying any correlation other than the passage of time—and I was blessed with more grandchildren, I seemed to be cursed with more foot issues. And with the Achilles problem came the admonition that I could no longer wear flats; now I had to wear wedges—not too high, not too steep. Then somehow I couldn’t wear shoes without backs, or sandals with thongs, and on and on it went. So I needed new shoes, but one never wants to part with beautiful shoes from one’s past; there is always the hope that they can be worn again.

And then along came Uggs. Really, it wasn’t my fault. I was simply passing by the shoe department, minding my own business, and there was an Ugg bootie in the exact terra cotta color I happened to be wearing. Yes, they were somewhat flat, but had just enough support that I could wear them. And they were so warm and comfy. Yes, they looked a little wide for my small feet, but my skirts are so long that I hardly noticed. And did I mention they were terra cotta? The next thing I knew, Ugg came out with a boot in my exact teal green. Well, what’s a woman to do? Years later, I still have—and wear—every pair of Uggs I ever bought. And they have somehow appeared in my life in every one of my colors! Really, not my fault at all.

But meanwhile, though my Ugg collection grew, my closet size did not. Enter my two youngest granddaughters, E and A, ages six and eight, respectively. It all started innocently enough. They wanted to come visit and play store. Using my closet. One look and they decided it would be a shoe store. They were in charge of setting up the displays and they were the sales force. And I, as the only available adult, was the customer. I treasure my time with these little people, so I tried on myriad pairs of my own shoes and carefully made my selections, all the while wondering when I would ever be able to wear those fabulous gladiator sandals or elegant metallic wedges again.

And as they had dredged all my shoes out of the darkest depths of my closet, I was forced to acknowledge that I was not nearly as organized as I thought I was. Marie Kondo, the Japanese organizing guru and author of The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, would not approve. Nor would my dear friend Marjorie, who long ago taught me the principles of a pared down, organized house. And as my dear granddaughters had to leave before they had the chance to clear out the “store” and re-stock the closet, that task was left to me. Suffice it to say that I didn’t have much energy left to do it well.

Then one day not long after, I watched six year old E ruthlessly purge and re-arrange her sock drawer, and I asked half in jest if she would like to organize my shoes. I was rather surprised and a bit nervous when she jumped at the chance. She came to my house and stood surveying my collection of footwear, shaking her head. She began saying things like, “This is really a mish-mash, Nana. It’s a good thing we’re doing this.” Then came, “Let’s put the sneakers and slippers on these shelves, and we’ll put the sandals on the closet floor.” She proceeded to do all of that, preferring I basically stay out of it, except to arrange by color once she’d gotten the categories set up.

Then came, “Nana, these are rain boots. You know it never rains. Let’s put them all the way in the back.” And then, “Now, out of these shoes, which do you wear the most? They’re going on this side where you can see them more easily.” And on she went. Yes, she’s six. Every once in a while she would point out a pair that was really worn out and demand that I get rid of it. I dutifully got a big black garbage bag, and began to wonder why people pay professional organizers when there are little ones like this around with such skill and boundless energy! I was much relieved when she declared that my Uggs, lined up on the top shelf above the same color clothing, could stay just as they were.

So now I had a very organized, though rather crowded, closet. You know what I mean—the sort of organization that is easy to maintain as long as you never actually take out a pair of shoes and then attempt to put them back later when you’re tired or in a hurry. So as time went on…well, you can guess.

Meanwhile, Marie Kondo came out with a sequel to her best-selling book entitled: Spark Joy: An Illustrated Master Class on the Art of Organizing and Tidying Up. I confess I haven’t finished it yet, but the basic premise in the first half is that you should hold up every item you own and decide if it sparks joy, and only keep what does. (For purely utilitarian items apparently you can muse about the joy that comes from using it and accomplishing what you need to.) I further confess that I have not had time to attempt the “spark joy” test with all my possessions, but I haven’t been able to get the joy concept out of my head either. And what I’ve realized is that there is little joy in gazing at a neatly arranged collection of shoes, so many of which are torture to wear.

And then along came my little darlings, A and E again, together for an afternoon. They wanted to play board games. Now I would do anything for them, but I am not a big fan of board games. So instead I said that I had a little project in mind. Whereupon E cocked her little head, narrowed her eyes at me and said, “Nana, did you make a mish-mash of your shoes again, after all my hard work?”

I sheepishly replied, “Not exactly,” and then went on to explain that I had decided it was time to say goodbye to the shoes I never wear. Apparently this is a lot more fun than a board game because they made a bee-line for my closet. I should stop here and explain that not only is E a natural organizer, but A is no slouch herself, and is also the daughter of a stylist. She plays “empty-out-the-entire-closet-and-put-outfits-together” with her friends. For fun.

They set about the task with great gusto. E said things like, “I never see you wear these. They should go, Nana,” and “Didn’t we already get rid of these? Why are they still here?”

A was prone to saying “What were you thinking, Nana? I don’t care if the color is perfect. These toes are waaay too pointy. You can’t wear these!” She commandeered a pair of black nylon rain booties for herself. They actually fit her (though she will probably out-grow them within six months), and she reminded me that “Black is so not your color. Why do you even have these?” Why, indeed?

They made me get a roll of those big black garbage bags. Some old shoes were obviously meant for garbage, and shoes in good condition would be donated, as none of my family members share my small shoe size (nor affinity for the colors and styles I wear!) We also made a pile of sparkly shoes for them to play dress-up. So out went the wedges whose heels were too steep. Out went the flats with no arch support. Out went the pumps with the toe boxes that pinched. Out went the thong sandals that caused excruciating pain. Out, out, out! It was long past time.

Once again, my Uggs, safely high up, out of reach and arranged by color, survived the purge. We spent a delightful afternoon, and when the girls left I took a good look at our handiwork. My shoe cabinet was half empty, as was the closet floor. The empty spaces made me take a deep breath in sheer relief. This kind of activity is very cleansing and even exhilarating. Besides the Uggs, I now had exactly two pairs of sneakers, three pairs of slippers, and four pairs of dress shoes and boots. This felt good! Very good! Except… Wait a minute! I had only one pair of sandals left—super comfortable, ten year old brown-burgundy sandals. That meant that once Ugg season had passed, if I wasn’t wearing my burgundy-colored clothes, I would have no shoes to wear!

Oh no! What now? The very last thing I wanted to do was buy more shoes! Thank goodness the weather had turned cold again. That day I was wearing my terra cotta color with the very first pair of Ugg booties I ever bought. But summer was coming, and the Valley where I live is hot and dry for many months every year. I was in big trouble!

But shoes notwithstanding, and with all due respect to the Japanese organizing guru, I realized something very important. It is not this shoe or that, nor even gazing at open spaces once the work is done, that sparks joy for me. The joy comes from spending this precious time with my delightful granddaughters. One day, all too soon, they will not find this activity so engaging. In the meantime I will unabashedly take advantage of their enthusiasm and talents. Next up, my scarves and shawls…

The post On Losing Shoes and Finding Joy appeared first on Xianna Michaels.

March 16, 2016

Kirkus Reviews rates Lily of the Valley “a gorgeously designed and illustrated book.”

A verse narrative follows the fortunes of a Jewish family through five generations after it immigrates to the United States.

In 1892, a Russian Jewish couple suffer a horrifying loss when their baby is murdered by Cossacks in a pogrom. They send their two remaining children, Basya and Laili, to the United States, because “in America everyone has a chance.” With their names changed to Bess and Lily at Ellis Island, the girls toil in a Lower East Side sweatshop. Lily dreams of making beautiful clothes for rich women and moving to warm, sunny Southern California, but realizes “Not for Lily’s family, no. / But a grandchild, maybe, one day would go.” Her daughters, Molly and Anna, join her at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company, where the girls survive the factory’s notorious fire, but their mother dies. Through two world wars and the Great Depression, Molly and her husband, Max, work hard and better their circumstances. Their daughter Lily and her husband prosper, sending their daughter Maxine to college. Not very religiously observant up till then, Maxine is drawn to the Chabad movement and Orthodox Judaism. She marries young and has five children while getting her Ph.D. in costume history, and fulfills her grandmother’s dream by moving to Los Angeles County’s San Fernando Valley. Maxine’s daughter Lily continues the family interest in fashion and style by starting her own clothing line (“Lily of the Valley”) after marrying and having children. Michaels (Mindel and the Misfit Dragons, 2014) offers a gorgeously designed and illustrated book, though its appearance may outweigh its entirely familiar story (Ellis Island, sweatshops, world wars, reclamation of one’s heritage). Still, it’s told with verve and a pleasing sense of things coming out right. Michaels employs an English sestet form that works well; it’s short enough to keep things moving, while the ABABCC structure lends an air of finality to each stanza. The rhyme and the sometimes singsong rhythm might make this seem a children’s book, but the content isn’t always kid-friendly: “[The Cossacks] stomped on the baby and slashed Mama’s side.”

A beautiful volume that tells a classic American story.

Read full review here at Kirkus Reviews.

The post Kirkus Reviews rates Lily of the Valley “a gorgeously designed and illustrated book.” appeared first on Xianna Michaels.

March 15, 2016

Why a Story in Verse?

“For the land beyond the Lower East Side

And New York’s endless stone and steel,

Where the other shore was three months’ ride—

California, where the gold was real.

The north was booming, but the southern part

Was the place that captured Lily’s heart.

A place they called Los Angeles where

It never rained, was never cold,

Where the scent of orange filled the air

And palm trees lined the streets of gold.

Not for Lily’s family, no.

But a grandchild, maybe, one day would go.”

(From Part 1- Lily)

People ask me all the time why I choose to write my stories in verse. It’s a very interesting question, especially since I don’t feel that I really do the choosing. My new book, Lily of the Valley—An American Jewish Journey, is a verse novella because it came to me in verse form. What do I mean by that? I certainly do not mean to imply that it just appeared before me fully formed as a poem. Far from it—I’m certainly not Mozart taking dictation! As with most poets and writers, whatever I am working on requires working, and re-working, over and over.

However, a big part of my creative process, and something I have always taught my creative writing students, is learning to be receptive. When I am receptive, open and wiling to listen, stories come to me. Characters talk to me, just as Lily began whispering to me on my morning walk many years ago. She began telling me her story, and I felt compelled to start taking notes.

But something else happens to me when a story starts coming. It tells me the form in which it needs to be told. Sometimes my stories come as prose, but more often that not they come as poems. Even the particular verse form comes; I do not choose it. My children’s book, Mindel and the Misfit Dragons, for instance, came in the four-line ballad stanza, while Lily of the Valley, a book for adults, is in sestets of iambic tetrameter. I may start to feel the lines flow through me, almost pump through, in which case I have to stop whatever I’m doing and grab a pen. Or else they may come in spurts at unexpected times of the day. A whole story certainly does not come at once, nor even a whole chapter. But enough lines and stanzas will come—and feel right for this story, feel right for these characters and their narrative voice—that I know I have my template. I know I have the structure, or more accurately perhaps the vessel, for telling the rest of the story.

Then the real work begins. The active listening, the drawing out, the shaping and paring, the writing and revising. It can take weeks, months or years, but there is a special joy in writing poetry—the musicality of it, the unique satisfaction of having the sound and sense of a stanza click, that is absolutely exhilarating.

Though I did not consciously choose to write Lily of the Valley as a verse novella, I do believe the verse form enhances the story in several ways. One is that it plays into the allegorical nature of the story. That is, Lily can be read as a narrative but also as symbolic of the whole American immigrant story. Since poetry at its core deals with essence, this comes through more clearly than if this were, say, a 600 page family saga. I once read an interesting analogy that the difference between a novel and a poem is like the difference between an oil painting and a piece of sculpture. The oil painting is rich in detail and many-layered, but the sculpture captures essence. There cannot be an extraneous bit of clay. So, too, a novel is rich in detail and vast in scope, but a poem captures essence; there cannot be an extraneous line. Another way I believe the verse form enhances this story is that poetry by its nature is lyrical. And for me there is something lyrical and haunting about Lily, which tells me that it could not have been written any other way.

I’m well aware that modern readers are not so accustomed to reading stories as poems. But once upon a time, before the invention of the printing press, almost all stories were told as poems. They were sung in castle halls, told before the fire in great manor houses, in forests and on desert sands. The rhyme and rhythm of poetry made the narratives easier for the bards and troubadours to remember. Literature began as an oral medium, and the earliest written stories continued the poetic tradition.

For me there is a certain pleasure that poetry provides the eye and ear. One reviewer captured this when she said that the experience of reading Lily was more like watching a musical than just seeing a movie. I’ve always loved musicals, and I love the way the musicality of poetry can propel a story. But mostly, I just let a story tell itself. And so Lily of the Valley is a verse novella. I sincerely hope that everyone will experience in reading this book the same delight that I felt in writing it.

The post Why a Story in Verse? appeared first on Xianna Michaels.

March 5, 2016

What Does That Sign Say?

When you open up my new book, Lily of the Valley—An American Jewish Journey, the first thing you see are the endpapers, or fly sheets. As with all hard covered books, these are the folded sheets with one half glued to the inside of the front cover and the other forming the first free page of the book. The back endpapers do the same in reverse. Sometimes these are simply blank, or solid-colored, or they may be decorated with recurring patterns or old maps or artwork.

I love to hand-illustrate my endpapers with a fountain pen. My first book, Mindel and the Misfit Dragons, depicts scenes from a medieval landscape. My new book, Lily of the Valley, shows a melange of images from the old-time San Fernando Valley, from the horse and cart and the old adobe on the left to the roadster on the right. That car is driving on a roadway lined with the bell markers identifying it as El Camino Real, the original trail of Spanish missions, later known as the 101 Freeway and Ventura Boulevard.

You can see all of that on the endpapers, but what really seems to draw everyone’s eye is the iconic sign embedded in the hills leading to the Valley. That sign with its huge white capital letters, recognized all over the country, dare I say the world… That sign that defines a region and that to this day everyone driving up the freeway toward the Valley can see… That sign that says… HOLLYWOODLAND???

Wait, no, it doesn’t. Surely the sign says HOLLYWOOD, doesn’t it? Hollywood, as in the place where stars are born and movies are made that reverberate round the world and down through the generations. Did the artist (in this case yours truly) make a mistake? What’s the story here?

Well, it turns out there is a story, and a fun bit of LA history at that. The sign was originally erected in 1923 as an advertisement for—wait for it—a local real estate development! The sign did indeed read “HOLLYWOODLAND” and referred to a new housing development in the hills above the Hollywood district of Los Angeles. Each wooden letter was 30 feet wide and 50 feet high, and was studded with light bulbs. It would flash in segments of “HOLLY”, “WOOD” and “LAND” and then the whole thing would light up.

It was originally intended to remain up for a year and a half. But this was the beginning of the rise of American cinema in Los Angeles, and the sign came to symbolize the burgeoning new industry and was left there. It deteriorated over time, however. And in the early 1940’s the sign’s official caretaker, driving while intoxicated, drove off the cliff behind the letter “H”. While he escaped injury, his 1928 Ford and the poor letter “H” did not. In 1949 the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce and the City of LA Parks Department repaired and rebuilt the sign. The letters “LAND” were removed, so the sign would reflect the district rather than a housing development. And they scuttled the light bulbs due to cost. This new iteration lasted till the 1970’s, but as it was built of wood and sheet metal, it, too, became sadly bedraggled with time.

Interestingly, it was Hugh Hefner, founder of Playboy magazine, who spearheaded a public campaign in 1978 to have the sign replaced with a more permanent structure. Nine donors gave $27,777.77 each to sponsor replacement letters, which were made of steel supported by steel columns on a concrete structure. Among the donors were Hefner himself, Gene Autry, Andy Williams and Alice Cooper. The new letters were 45 feet tall and between 31 and 39 feet wide. The new sign with its nine letters spelling “HOLLYWOOD” was unveiled in November 1978 and was refurbished and repainted white in 2005.

As a sign of the times (no pun intended), residents in the neighborhoods around the sign complain of all the traffic congestion caused by tourist buses, vans and cars clogging the curving hillside roads, filled with people hoping to glimpse the iconic letters up close. The locals apparently post “Tourist Go Away” signs and the Hollywood Sign Trust has convinced various online mapping services to direct people to viewing platforms such as the Griffith Observatory and the Hollywood and Highland Center. The sign is actually located on steep terrain and there are now barriers to prevent unauthorized access as well as a security system surrounding the letters.

So to all those with a burning desire to view this iconic piece of local history, may I offer a suggestion? There is truly no need to disturb the residents. Just take a ride on the Hollywood Freeway (known as US Route 101 until it becomes the 170 in the Valley), from downtown LA or the Hollywood area itself north toward the San Fernando Valley. On any given day the traffic is so bad that you have all the time in the world to gaze in awe at the iconic sign that symbolizes the Dream Factory.

Meanwhile, back to the endpapers of Lily of the Valley, does anyone want to guess whose house is tucked on the upper right hand side, surrounded by palm trees and utterly at home in the Valley? Hint: It dates from 1929, when the sign did, indeed, read “HOLLYWOODLAND.”

The post What Does That Sign Say? appeared first on Xianna Michaels.

March 1, 2016

Introducing Lily

Today is the official launch date of my new book, Lily of the Valley—An American Jewish Journey. I am truly thrilled to be sharing this book with everyone, and what more fitting day for me personally to introduce you to Lily? I don’t just mean Lily, the book, but Lily the woman, the first of five generations of strong, resilient women who held tightly to dreams passed from mother to daughter for those five generations.

People ask writers all the time where their ideas come from, and there may be as many answers as there are books. Every writer has his or her own process, and every book its own path. Usually as I write a story the characters live inside of me for all the months—or even years—that it takes me to tell their story. Then they rather gracefully bow out, making way for the next group of people, the next narrative, that will fill my consciousness.

But Lily is different. From the moment she came to me she has been part of me. It’s as if she lives deep inside of me. But who is Lily?

Perhaps I ought to start at the beginning. Many years ago on my daily morning walk I began to hear snippets of a story coming in rhymed poetry. It was as if a little bird were sitting on my shoulder, whispering to me. Her name was Lily. She had barely survived a pogrom in Eastern Europe and her parents put her on a ship bound for the Goldene Medina, the Golden Land; America, the land of freedom and the promise of a better life. She came here, toiled in a sweatshop and dreamed. She dreamed of designing beautiful gowns, and of a golden valley way out West,

” …the place of palms and a mountain pass

That led to a sun- drenched valley floor

With walnut groves and golden grass—

Open space, an open door,

And unlike the valley of her birth,

Without the blood that soaked the earth.”

(Part I – Lily)

Lily knew that her dreams would not be fulfilled in her lifetime, but she held fast to them for her daughter, her granddaughter, for all those who would come. Everyday I would return from my walk and write down what she told me. But I had no idea what to do with any of it. And then I got a call from Ruchie Stillman, who was coordinating the banquet for Chabad of the Valley in Encino, California, under the direction of Rabbi Joshua Gordon, of blessed memory, and his wife Deborah. They asked if I would step in at the last minute to perform a fifteen poem for the banquet. I had no idea how I could pull off such a thing in just a few days. Then I remembered Lily, whispering in my ear. Lily, who so much wanted to be heard. It was Ruchie who helped me realize that her story—about pursuing the American Dream while losing the connection to observant Judaism and then coming back—was ultimately a Chabad story.

The story started pouring out of me. I wrote at home, on my morning walk, in elevators, in the car. Lily talked and I transcribed, then later pared and polished and created a poem that I could perform. When I finished my reading of “Lily of the Valley” at the banquet, people asked it they could buy a copy, but I knew it wasn’t time.

When I returned to Lily more than a decade later, she began whispering to me again, fleshing out her story beyond what could fit into a fifteen minute reading. But who is Lily to me? Who is she that even after all these years I cry every time I read or write or even talk about her and her dreams? The dreams that wouldn’t die, even when she did, even if they took generations to fulfill? Who is Lily?

I do not know.

One reviewer thought she was my grandmother. Not so. This book is not autobiographical. Lily came here a generation before my grandmothers and her story is different. There are parallels in this book with my family’s history, just as I’m sure there are parallels for many people whose ancestors came here through Ellis Island, desperate and hopeful, seeking a better life. But this is a work of fiction; it is not my story. It is Lily’s and that of the women who came after her. Yet my connection is soul-deep.

I do not know who Lily was, but I do know that in many ways this book is my love letter to America, the Golden Land that rescued Lily from a life of fear, persecution and near destitution, just as it did my grandparents. It is a land that promised—and still promises—immigrants from all over that if they work hard, their children’s lives will be better; that pursuing the American Dream does not mean having to give up worshipping G-d in the way of their ancestors, the way of their conscience.

I have published Lily’s story now in part as my way of expressing my gratitude to the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of blessed memory. I thank the Rebbe for his beautiful teachings and many blessings, that have helped set the trajectory of my life. It is a sad irony for me that Rabbi Joshua Gordon, whose long-ago request helped bring Lily to life, tragically passed away just weeks before the publication of this book.

And I share this story now because I’ve known from the beginning, all those years ago, that Lily’s story is meant to touch other lives in the way she has touched mine. I am honored that she chose me to tell her story. I hope that I have done right by her, and that my readers will enjoy her story, and perhaps be inspired, all over again, by the American Dream that we all share.

The post Introducing Lily appeared first on Xianna Michaels.

February 14, 2016

Foreword Reviews gives Lily of the Valley a five star review

Lily of the Valley is an elegantly bound poetic volume that celebrates the varied inheritances of Jewish American women with poignancy.

Lily of the Valley is Xianna Michaels’s graceful and affecting poetic saga, the story of five generations of Jewish American women navigating the promises of the New World.

The volume opens on a pogrom that rips through a shtetl, rending families irrevocably. Young Laili is sent with her her sister Basya to New York, with the hope that they’ll be able to enjoy more freedoms there. Laili’s name is anglicized by Ellis Island officials; now known as “Lily,” she finds work in a sweatshop sewing clothing. As she sews, she dreams of an easier life for her children, preferably in the golden valleys of the West.

Though tragedies continue to fall upon her family—a shop fire kills one matriarch; a son abandons his tradition and family to pursue life on his own; a daughter returns to Europe, too near to the Holocaust for safety—so, too, do the generations that follow Lily find their fortunes in America increasing. They become business owners, college graduates, parents, and the pursuers of old family dreams. Their Judaism ebbs and flows in proportion to the challenges they face—work on Shabbat gives way to the avoidance of the mikveh, compromises are made with the observance of mitzvot, especially around kashrut. Yet through it all, they maintain a sense of connection to their tradition, and to the family members who sacrificed so much to provide them with opportunities.

Lily of the Valley is written in English sestet form, a rhyme scheme that initially requires some getting used to; the violence of the opening pogrom fits uneasily with the apparent jauntiness of the poetic formula. Conjunctions are employed a bit too freely, and not every end rhyme is a comfortable fit. Related misgivings give way beneath the charm of Michaels’s verses, though. These lines breathe life into the women they focus on: the first Lily is a determined dreamer, her daughter Molly a believer, her daughter Lily a stylish girl who dusts off family aspirations. Each woman, in the limited lines allotted to her, is fleshed out well, particularly in relation to the decisions she makes around religious observance.

The intrafamily loyalty and support conveyed throughout Lily of the Valley is inspirational without being cloying, and the book moves from generation to generation with significant emotional prowess. This book is impressive for the balances it strikes: managing to be feminist, even as Lily’s great-granddaughter moves back toward observance, to the surprised delight of her nonobservant family; achieving a well-rounded picture of Jewish American history, though in the span of a few stanzas each on just fifty pages. The end result is a project certain to woo readers with its loveliness. Its beautiful, classic packaging, paired with the delicate, scene-setting illustrations that run throughout, make the project an all the more likely candidate for family treasure status.

Lily of the Valley is an elegantly bound poetic volume that celebrates the varied inheritances of Jewish American women with poignancy.

Reviewed by Michelle Anne Schingler

February 10, 2016

Read full review here on Forward Reviews.

The post Foreword Reviews gives Lily of the Valley a five star review appeared first on Xianna Michaels.