Gillian Bradshaw's Blog, page 2

June 4, 2012

Pageants

Ancient cities were fond of pageants and processions. Athena, Demeter, Dionysos, Zeu, Isis--they all seemed to have liked elaborate parades. Statues of the gods would be dressed gorgeous draperies and carried throughout the city, accompanied by handsome young horsemen got up in their best on neighing steeds; priests in magnificent robe;, musicians playing lyres, flutes, sistra; celebrants crying 'euoi, euoi!' or 'ite Bacchai, ite Bacchai', as the case might be; sacrificial cattle with gilded horns, garlanded with roses or ivy; incense and offerings. Hellenistic kings paid for floats on wheeled carts, showing scenes from mythology or of battles where they'd defeated their enemies; crowds would be showered with coins, or flowers, or nuts and sweetmeats. The Rhodians, and other naval powers, went in for naval processions, with their magnificently decorated ships processing past the cheering crowds on shore. The Romans were as eager as the Greeks: their triumphal processions were probably the most elaborate of all ancient pageants, and were so intoxicating to the triumphing generals that a slave had to be appointed to whisper in the victorious ear, 'Remember that you are mortal!'

When the Roman Empire went Christian, the processions carried on, though the excuse for them switched from gods and glory to God's glory: North Africans used to celebrate saints' days by processing round the churches, drinking heartily at each, a kind of sanctified pub crawl which drew occasional criticism from their bishops. Byzantine basileis and medieval kings eagerly seized any excuse for show and display, and Renaissance geniuses contributed mechanical contrivances, playlets, and painted backdrops; gunpowder allowed fireworks.

It all seems very jolly, but recent experience has left me wondering how much the average woman in the street actually saw of all this cheerful vainglory. We went down to London yesterday to watch the Diamond Jubilee river pageant, but the crowds were so thick I couldn't even see the river. I did just about glimpse the queen, because the royal barge was tall enough that the top was briefly visible through binoculars as it departed downstream. All the rest--the flotilla of rowboats; the barges of bells and musicians; the fire brigade's working boat imitating a moving fountain, the Dunkirk little ships--was hidden behind a wall of backs. I only know about them because I looked at the BBC website afterwards.

I'm not really sorry I went, though. It's something, to be able to say 'I was there' at what may prove to be the monarchy's last hurrah, and there was entertainment in looking at the crowds--the girls with the union jack lipstick; the children waving flags; the people in the queen and Prince Charles masks; the man opening a bottle of beer against the curb. A brass band emerged twice from a private party on a moored boat and played 'Rule Britannia', 'Land of Hope and Glory', and 'God Save the Queen', which the crowd sang lustily. I just wonder how many people at, say, Augustus's triumph, saw no more than the top of the model of the Pharos going slowly past above a sea of heads.

When the Roman Empire went Christian, the processions carried on, though the excuse for them switched from gods and glory to God's glory: North Africans used to celebrate saints' days by processing round the churches, drinking heartily at each, a kind of sanctified pub crawl which drew occasional criticism from their bishops. Byzantine basileis and medieval kings eagerly seized any excuse for show and display, and Renaissance geniuses contributed mechanical contrivances, playlets, and painted backdrops; gunpowder allowed fireworks.

It all seems very jolly, but recent experience has left me wondering how much the average woman in the street actually saw of all this cheerful vainglory. We went down to London yesterday to watch the Diamond Jubilee river pageant, but the crowds were so thick I couldn't even see the river. I did just about glimpse the queen, because the royal barge was tall enough that the top was briefly visible through binoculars as it departed downstream. All the rest--the flotilla of rowboats; the barges of bells and musicians; the fire brigade's working boat imitating a moving fountain, the Dunkirk little ships--was hidden behind a wall of backs. I only know about them because I looked at the BBC website afterwards.

I'm not really sorry I went, though. It's something, to be able to say 'I was there' at what may prove to be the monarchy's last hurrah, and there was entertainment in looking at the crowds--the girls with the union jack lipstick; the children waving flags; the people in the queen and Prince Charles masks; the man opening a bottle of beer against the curb. A brass band emerged twice from a private party on a moored boat and played 'Rule Britannia', 'Land of Hope and Glory', and 'God Save the Queen', which the crowd sang lustily. I just wonder how many people at, say, Augustus's triumph, saw no more than the top of the model of the Pharos going slowly past above a sea of heads.

Published on June 04, 2012 07:01

May 21, 2012

The Netherlands

I've just returned from a weekend in the Netherlands. Every time I visit that fortunate country, I'm struck afresh by what a nice place it is.

The first time I visited was in March 1984. I had two very small children in tow, one in a pushchair and one in a babysling. I was amazed and delighted by the Dutch response: they liked small children. In restaurants, instead of frowning or saying 'we don't admit children', they would ask 'May we give the little boy an ice cream?' (yes!) I did a lot of travelling on trams and buses, and not once did I carry the pushchair onto the bus: if there was no one else waiting beside me to pick it up and carry it carefully aboard, a passenger would leap off the tram to do the office, grinning at the suspicious toddler and trying to talk to him. It was no wonder, I thought, that the Dutch grow up so sensible and well-adjusted.

I've been back several times since. I've even read up quite a lot of the history for the stalled next book. (Now I know where they get it from: they were founded by a guy who was in favour of religious toleration despite living in the 17th C., and they had the most developed social care in the world, with a comprehensive system of welfare back in 1650--which, pace the right wing, was a Golden Age economically as well as culturally.) Every time I go I'm struck by:

I've been back several times since. I've even read up quite a lot of the history for the stalled next book. (Now I know where they get it from: they were founded by a guy who was in favour of religious toleration despite living in the 17th C., and they had the most developed social care in the world, with a comprehensive system of welfare back in 1650--which, pace the right wing, was a Golden Age economically as well as culturally.) Every time I go I'm struck by:

1) bicycles! They seem to outnumber cars ten to one. All the civic amenities that other countries build only for cars the Dutch build for cycles as well: parking at station and in city centres, tracks and roads, etc.

2) public transport. Trains and buses are frequent, cheap, and reliable.

3) cleanliness. The air and water are so unpolluted that during the last visit--to South Holland--I saw in the city centres, breeding wildfowl that included crested and little grebes, white storks, herons, tufted ducks, coots, moorhens, barnacle and greylag and Canada geese, as well as a couple of exotics and ubiquitous mallard.

4) the way everybody speaks perfect English. It's uncanny. I don't speak perfect Dutch. I speak some French, a bit of German and modern Greek--but nothing of it as well as everybody spoke English.

5) how livable it all seems. In fact, the question I'm always left with after I return from the Netherlands is why other countries aren't more like them.

The first time I visited was in March 1984. I had two very small children in tow, one in a pushchair and one in a babysling. I was amazed and delighted by the Dutch response: they liked small children. In restaurants, instead of frowning or saying 'we don't admit children', they would ask 'May we give the little boy an ice cream?' (yes!) I did a lot of travelling on trams and buses, and not once did I carry the pushchair onto the bus: if there was no one else waiting beside me to pick it up and carry it carefully aboard, a passenger would leap off the tram to do the office, grinning at the suspicious toddler and trying to talk to him. It was no wonder, I thought, that the Dutch grow up so sensible and well-adjusted.

I've been back several times since. I've even read up quite a lot of the history for the stalled next book. (Now I know where they get it from: they were founded by a guy who was in favour of religious toleration despite living in the 17th C., and they had the most developed social care in the world, with a comprehensive system of welfare back in 1650--which, pace the right wing, was a Golden Age economically as well as culturally.) Every time I go I'm struck by:

I've been back several times since. I've even read up quite a lot of the history for the stalled next book. (Now I know where they get it from: they were founded by a guy who was in favour of religious toleration despite living in the 17th C., and they had the most developed social care in the world, with a comprehensive system of welfare back in 1650--which, pace the right wing, was a Golden Age economically as well as culturally.) Every time I go I'm struck by:1) bicycles! They seem to outnumber cars ten to one. All the civic amenities that other countries build only for cars the Dutch build for cycles as well: parking at station and in city centres, tracks and roads, etc.

2) public transport. Trains and buses are frequent, cheap, and reliable.

3) cleanliness. The air and water are so unpolluted that during the last visit--to South Holland--I saw in the city centres, breeding wildfowl that included crested and little grebes, white storks, herons, tufted ducks, coots, moorhens, barnacle and greylag and Canada geese, as well as a couple of exotics and ubiquitous mallard.

4) the way everybody speaks perfect English. It's uncanny. I don't speak perfect Dutch. I speak some French, a bit of German and modern Greek--but nothing of it as well as everybody spoke English.

5) how livable it all seems. In fact, the question I'm always left with after I return from the Netherlands is why other countries aren't more like them.

Published on May 21, 2012 10:14

May 15, 2012

Conventions that suspend reality: 1 Injury and illness

There are some conventions in popular fiction that are so well-established that we don't even notice how much they defy real-life experience unless we sit down and think about it.

My favourite is the knock on the head. There are any number of books, films and television programs where the hero is knocked on the head, and, after a spell of unconsciousness, climbs to his feet, defeats the bad guy, and gets the girl--or, alternatively, where he knocks a couple of bad guys on the head, who get up a bit later, rub their skulls, and set off in hot pursuit. Nobody blinks at this--despite the fact that in real life we regard being knocked unconscious as a very serious matter, one that requires a trip to hospital and an X-ray and bed-rest. We know very well that head injuries are dangerous, but we do not apply that knowledge to the world of fiction.

Of course popular fiction has a strange attitude to illness and injury in general. Try to imagine James Bond catching a cold! Infected cuts, conjunctivitis, piles, diarrhea and the other ills that flesh is heir to are, I am sure, found far more frequently in real life than in fiction. Even more interesting is the way characters are unimpeded by injuries which I, for one, would find disabling. I have to take the evening off if I have a tooth out, but some heroes can scale a cliff after being shot through the shoulder--and, of course, operatic sopranos and tenors can sing gloriously while suffocating to death or dying of tuberculosis.

There are, of course plenty of books that deal honestly with injury and illness and make every effort to get medical details right. What is strange is that the books which don't get away with it so easily. The world of these books is, after all, ostensibly our own--but we don't apply our own rules to it, and usually don't even notice that omission.

My favourite is the knock on the head. There are any number of books, films and television programs where the hero is knocked on the head, and, after a spell of unconsciousness, climbs to his feet, defeats the bad guy, and gets the girl--or, alternatively, where he knocks a couple of bad guys on the head, who get up a bit later, rub their skulls, and set off in hot pursuit. Nobody blinks at this--despite the fact that in real life we regard being knocked unconscious as a very serious matter, one that requires a trip to hospital and an X-ray and bed-rest. We know very well that head injuries are dangerous, but we do not apply that knowledge to the world of fiction.

Of course popular fiction has a strange attitude to illness and injury in general. Try to imagine James Bond catching a cold! Infected cuts, conjunctivitis, piles, diarrhea and the other ills that flesh is heir to are, I am sure, found far more frequently in real life than in fiction. Even more interesting is the way characters are unimpeded by injuries which I, for one, would find disabling. I have to take the evening off if I have a tooth out, but some heroes can scale a cliff after being shot through the shoulder--and, of course, operatic sopranos and tenors can sing gloriously while suffocating to death or dying of tuberculosis.

There are, of course plenty of books that deal honestly with injury and illness and make every effort to get medical details right. What is strange is that the books which don't get away with it so easily. The world of these books is, after all, ostensibly our own--but we don't apply our own rules to it, and usually don't even notice that omission.

Published on May 15, 2012 15:49

May 4, 2012

The Vindolanda tablets

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Vindolanda_tablet_291.jpg#filelinks

Now that Mary Beard's 'Meet the Romans' series has, alas, ended, I've been reflecting on her achievement in making epigraphy--one of the driest disciplines--not merely exciting but televisual. It is unusual, and she and the BBC both deserve credit for it.

It is not ever thus. A couple of years ago 'Time Team' held an audience vote to decide the most important find from Roman Britain. I don't remember all the items, and, indeed, so un-memorable was the winner that it's already disappeared from the first four or five pages of Google. There was the bas-relief from the Antonine Wall, I remember, the one that proudly proclaimed the (short-lived) Roman expansion into Scotland, which is now in the Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. I think the Medusa head from Bath was on the list as well, and the beautiful Ribchester cavalry helmet, and the sculptures from the Temple of Mithras in London--all beautiful objects, and if you're not familiar with them, google them and have a look. What struck me at the time, though, was that the most important Roman find wasn't even on the list.

I can see why 'Time Team' didn't like them. I have to admit that they don't look like much. You can't even read them in their natural blackened state: the texts only emerged when they were photographed using every available trick of light and filtering; when they did emerge, their cursive scrawl was so hard to read that at first some people doubted whether they were even in Latin. Nonetheless, few historians would deny their enormous significance.

To begin with, until they were found it was thought that--as their discoverer, Robin Birley put it-- 'the prospect of ink writing from the Roman period being found in Britain was. . .impossible.' There were inscriptions, some graffiti, a handful of references in Roman texts, but actual Roman documents? They would surely have rotted away in the damp climate! It's counter-intuitive that waterlogged soil, sealed from the air, can actually preserve wood and leather.

Next, there's the form of the tablets: thin sheets of wood, scored down the center and folded. There had been a couple of obscures references in Roman texts, but not enough to shake the view that Romans generally wrote on papyrus or not wax tablets. The Vindolanda finds were the first indication that in northerly climes the Romans normally wrote on wood. More and more tablets have turned up in other sites, now that archaeologists know what to look for--though none as well-preserved or as rich as the finds from Vindolanda.

The main thing that makes the Vindolanda tablets so important, though, is what is written on them: a glimpse into Roman life on a border fort that we simply couldn't have obtained any other way than time travel. Letters of recommendation; letters of complaint; lists of supplies, with prices. There's an 'intelligence' report about the local British warriors, dismissing them contemptuously as ill-equipped 'Brittunculi'--a sneering diminutive. There is a letter to an ordinary soldier from his family, saying that they've sent him socks, two pairs of sandals, and two sets of underpants--'subligariorum duo'. Underpants! Now we know what all those stern centurions wore beneath their tunics! This is the only Latin reference to them!

The letter I love most, and perhaps the most famous of them all, is an invitation to a birthday party. As Birley points out, it would be remarkable anywhere it was found, because it contains the earliest writing known to have been penned by a Roman woman: while the main text has been penned smoothly by a scribe, Claudia Severa has added a note in the corner in her own spiky handwriting: 'Sperabo te, soror. Vale, soror, anima mea, ita valeam, karissima et (h)ave.'--'I will expect you, sister, Farewell, sister, my soul, as I hope to prosper, dearest, and greetings'.

You still get plenty of textbooks telling you that Roman girls didn't go to school and that few of them outside the most aristocratic circles would have been able to read : here we have a woman on the far fringe of the Roman Empire, the wife of the prefect of a mere auxiliary cohort--a man who was himself probably the first in his family to obtain the citizenship--sending gushing personal notes to her friend. Its mere existence puts that notion of female illiteracy in doubt. Beat that, you marble statue-hunters!

Now that Mary Beard's 'Meet the Romans' series has, alas, ended, I've been reflecting on her achievement in making epigraphy--one of the driest disciplines--not merely exciting but televisual. It is unusual, and she and the BBC both deserve credit for it.

It is not ever thus. A couple of years ago 'Time Team' held an audience vote to decide the most important find from Roman Britain. I don't remember all the items, and, indeed, so un-memorable was the winner that it's already disappeared from the first four or five pages of Google. There was the bas-relief from the Antonine Wall, I remember, the one that proudly proclaimed the (short-lived) Roman expansion into Scotland, which is now in the Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. I think the Medusa head from Bath was on the list as well, and the beautiful Ribchester cavalry helmet, and the sculptures from the Temple of Mithras in London--all beautiful objects, and if you're not familiar with them, google them and have a look. What struck me at the time, though, was that the most important Roman find wasn't even on the list.

I can see why 'Time Team' didn't like them. I have to admit that they don't look like much. You can't even read them in their natural blackened state: the texts only emerged when they were photographed using every available trick of light and filtering; when they did emerge, their cursive scrawl was so hard to read that at first some people doubted whether they were even in Latin. Nonetheless, few historians would deny their enormous significance.

To begin with, until they were found it was thought that--as their discoverer, Robin Birley put it-- 'the prospect of ink writing from the Roman period being found in Britain was. . .impossible.' There were inscriptions, some graffiti, a handful of references in Roman texts, but actual Roman documents? They would surely have rotted away in the damp climate! It's counter-intuitive that waterlogged soil, sealed from the air, can actually preserve wood and leather.

Next, there's the form of the tablets: thin sheets of wood, scored down the center and folded. There had been a couple of obscures references in Roman texts, but not enough to shake the view that Romans generally wrote on papyrus or not wax tablets. The Vindolanda finds were the first indication that in northerly climes the Romans normally wrote on wood. More and more tablets have turned up in other sites, now that archaeologists know what to look for--though none as well-preserved or as rich as the finds from Vindolanda.

The main thing that makes the Vindolanda tablets so important, though, is what is written on them: a glimpse into Roman life on a border fort that we simply couldn't have obtained any other way than time travel. Letters of recommendation; letters of complaint; lists of supplies, with prices. There's an 'intelligence' report about the local British warriors, dismissing them contemptuously as ill-equipped 'Brittunculi'--a sneering diminutive. There is a letter to an ordinary soldier from his family, saying that they've sent him socks, two pairs of sandals, and two sets of underpants--'subligariorum duo'. Underpants! Now we know what all those stern centurions wore beneath their tunics! This is the only Latin reference to them!

The letter I love most, and perhaps the most famous of them all, is an invitation to a birthday party. As Birley points out, it would be remarkable anywhere it was found, because it contains the earliest writing known to have been penned by a Roman woman: while the main text has been penned smoothly by a scribe, Claudia Severa has added a note in the corner in her own spiky handwriting: 'Sperabo te, soror. Vale, soror, anima mea, ita valeam, karissima et (h)ave.'--'I will expect you, sister, Farewell, sister, my soul, as I hope to prosper, dearest, and greetings'.

You still get plenty of textbooks telling you that Roman girls didn't go to school and that few of them outside the most aristocratic circles would have been able to read : here we have a woman on the far fringe of the Roman Empire, the wife of the prefect of a mere auxiliary cohort--a man who was himself probably the first in his family to obtain the citizenship--sending gushing personal notes to her friend. Its mere existence puts that notion of female illiteracy in doubt. Beat that, you marble statue-hunters!

Published on May 04, 2012 04:58

April 27, 2012

Mary Beard on the Romans

When some new author or television presenter boasts that he or she will show us Antiquity as never before, usually there are two possibilities: one, that they're a crackpot; two, that they're about to present information that classicists have known for yonks but which the general public might still find surprising. Mary Beard's new series on the Romans comes the closest I've ever seen to delivering on the initial promise. I'd seen a lot of the stuff she was presenting the other night, but some of it was delightfully new.

I've walked past that building next to the white marble wedding cake of the Victor Emanuel monument; I knew from the bricks it was ancient, but I hadn't realized it was an insula--a Roman apartment block. I knew that the ground floor of an insula was the best place to live, and that the higher up you went the more uncomfortable it got--Juvenal had told me that--but I hadn't realized how small the upper rooms were. Dr. Beard lay down on the dusty floor to show how little space the tenants must have had, and then suggested that whole families might have shared it--that perhaps a Roman woman had given birth there. With that image she brought a whole world to life.

Wonderful woman. Some of the commentators on the series have remarked on how great it is to see a middle-aged woman who isn't glamourous and who evidently cares much more about her subject than about her looks and her clothing, presenting a prime-time television series. Yes. It is is. It's also great to see a proper classicist on the screen--particularly one from Newnham, my old college (Yay!) Dr Beard is heavily reliant on epigraphy, which is one of the least glamourous--or at least, least televisual--of disciplines. In any museum the inscriptions are usually stacked up along the walls or in the basement, while the glamourous objects--statues, jewellery, weapons--take pride of place in the glass cases in the middle of the room. Deciphering the things takes time and effort. Usually they're fragmentary; always they're written without breaks between the words and often with unfamiliar letter forms or abbreviations. They are not exciting things to look at. I like them, but usually I skim them, picking up whatever I can get easily and abandoning the rest.

Wonderful woman. Some of the commentators on the series have remarked on how great it is to see a middle-aged woman who isn't glamourous and who evidently cares much more about her subject than about her looks and her clothing, presenting a prime-time television series. Yes. It is is. It's also great to see a proper classicist on the screen--particularly one from Newnham, my old college (Yay!) Dr Beard is heavily reliant on epigraphy, which is one of the least glamourous--or at least, least televisual--of disciplines. In any museum the inscriptions are usually stacked up along the walls or in the basement, while the glamourous objects--statues, jewellery, weapons--take pride of place in the glass cases in the middle of the room. Deciphering the things takes time and effort. Usually they're fragmentary; always they're written without breaks between the words and often with unfamiliar letter forms or abbreviations. They are not exciting things to look at. I like them, but usually I skim them, picking up whatever I can get easily and abandoning the rest.

Of course, inscriptions tell you all sorts of things that objects can't: people's names, their occupations, what they cared about, how they died. Scholars have been using them for years and years, but even to other scholars Inscriptiones Graecae Selectae is mostly dry as dust. It is to Mary Beard's credit that she can sift through this information and find just the bit that will connect to a wide audience and make the people come alive. Oh, she exaggerates and sometimes over-eggs the pudding, but better eggy pudding than dust! It's to the BBC's credit, too, that they've trusted her to make the stones speak, even if they do resort to gimmicks occasionally.

I don't want television much. Actually, I suppose this is the only series I've watched this year. Pity there aren't more like it!

I've walked past that building next to the white marble wedding cake of the Victor Emanuel monument; I knew from the bricks it was ancient, but I hadn't realized it was an insula--a Roman apartment block. I knew that the ground floor of an insula was the best place to live, and that the higher up you went the more uncomfortable it got--Juvenal had told me that--but I hadn't realized how small the upper rooms were. Dr. Beard lay down on the dusty floor to show how little space the tenants must have had, and then suggested that whole families might have shared it--that perhaps a Roman woman had given birth there. With that image she brought a whole world to life.

Wonderful woman. Some of the commentators on the series have remarked on how great it is to see a middle-aged woman who isn't glamourous and who evidently cares much more about her subject than about her looks and her clothing, presenting a prime-time television series. Yes. It is is. It's also great to see a proper classicist on the screen--particularly one from Newnham, my old college (Yay!) Dr Beard is heavily reliant on epigraphy, which is one of the least glamourous--or at least, least televisual--of disciplines. In any museum the inscriptions are usually stacked up along the walls or in the basement, while the glamourous objects--statues, jewellery, weapons--take pride of place in the glass cases in the middle of the room. Deciphering the things takes time and effort. Usually they're fragmentary; always they're written without breaks between the words and often with unfamiliar letter forms or abbreviations. They are not exciting things to look at. I like them, but usually I skim them, picking up whatever I can get easily and abandoning the rest.

Wonderful woman. Some of the commentators on the series have remarked on how great it is to see a middle-aged woman who isn't glamourous and who evidently cares much more about her subject than about her looks and her clothing, presenting a prime-time television series. Yes. It is is. It's also great to see a proper classicist on the screen--particularly one from Newnham, my old college (Yay!) Dr Beard is heavily reliant on epigraphy, which is one of the least glamourous--or at least, least televisual--of disciplines. In any museum the inscriptions are usually stacked up along the walls or in the basement, while the glamourous objects--statues, jewellery, weapons--take pride of place in the glass cases in the middle of the room. Deciphering the things takes time and effort. Usually they're fragmentary; always they're written without breaks between the words and often with unfamiliar letter forms or abbreviations. They are not exciting things to look at. I like them, but usually I skim them, picking up whatever I can get easily and abandoning the rest.Of course, inscriptions tell you all sorts of things that objects can't: people's names, their occupations, what they cared about, how they died. Scholars have been using them for years and years, but even to other scholars Inscriptiones Graecae Selectae is mostly dry as dust. It is to Mary Beard's credit that she can sift through this information and find just the bit that will connect to a wide audience and make the people come alive. Oh, she exaggerates and sometimes over-eggs the pudding, but better eggy pudding than dust! It's to the BBC's credit, too, that they've trusted her to make the stones speak, even if they do resort to gimmicks occasionally.

I don't want television much. Actually, I suppose this is the only series I've watched this year. Pity there aren't more like it!

Published on April 27, 2012 07:36

April 19, 2012

Bad Guys

At the moment I'm doing quite a lot of childminding of my four year old grandson. Like most small boys, he loves to set up bad guys which are resoundingly vanquished by good guys. At the moment, both the good guys and the bad ones are robots. The bad robots look the part, but there isn't really much in their behaviour to distinguish them from the good ones: both sides are loyal to their own and ferocious toward their opponents. There is some token pretence of 'evil plans' (usually for world domination) on one side, but that's just an excuse for a lot of blam blam blam!

At the moment I'm doing quite a lot of childminding of my four year old grandson. Like most small boys, he loves to set up bad guys which are resoundingly vanquished by good guys. At the moment, both the good guys and the bad ones are robots. The bad robots look the part, but there isn't really much in their behaviour to distinguish them from the good ones: both sides are loyal to their own and ferocious toward their opponents. There is some token pretence of 'evil plans' (usually for world domination) on one side, but that's just an excuse for a lot of blam blam blam!I hope that as my grandson grows up he'll find this Manichaean dichotomy a bit limiting. I find fiction a lot more interesting when the good guys have to work at being good--that is, struggle to make moral choices in a difficult world--and I like my bad guys to be intelligibly bad. A certain amount of moral ambiguity is almost required for literary fiction, but I like it even in the stuff I read purely for fun. I don't mean that I want to root for the bad guy, a la American Psycho, but I want the bad guys' motives to be understandable. In too many novels and films they're like my grandson's bad robots: they're bad because the good guys need somebody to fight. Blam blam blam!

Modern authors have come up with various ways to denote a character as bad. At the moment the most popular is to make him an Islamic terrorist. (Fifty years ago he would have been a Communist spy.) Then there are serial killers. Real serial killers do exist, of course, but I'm sure fictional ones outnumber them ten to one. Terrorists and serial killers have two advantages: they are automatically evil, and they automatically make your hero, however grubby, look good--because anybody looks good next to a terrorist or a serial killer. OK, I can enjoy a book where the evil terrorist plot is thwarted or the killer caught--but there's always a certain uneasiness mingled with the pleasure. I have been invited to disengage the sense of moral discrimination and sympathy which governs my ordinary life; real problems and real sufferings are being used to generate excitement without any attempt to understand their causes. This may or may not be immoral--but it's certainly unrealistic, and, on the author's part, lazy.

Some authors--I'm thinking of Patricia Cornwall and her ilk, here--not only rely on serial killers, but use another substitute for motive: sexism. Sexism and racism are certainly real and abominable, but in the real world they're normally negative: the victim doesn't get the job, the promotion, the contract; in a crisis they don't get the trust and support a white man would expect. It's rare for somebody to actively work to ruin an innocent purely on the grounds of sex or race when that innocent isn't threatening any of their own interests: for one thing it takes effort; for another, it's illegal. I know it happens, when the perpetrator is crazy enough--but it isn't common. Cornwall seems to have at least one sexism-motivated plot against the heroine per book. Again, unrealistic and lazy--and boring. I stopped reading her because of it.

George Bernard Shaw once said that he tried to give the best speech in every play to the villain. He wanted to make that villain's opposition intelligible, to deepen the moral dilemma and make the hero's choices more fraught and more dramatic. If the bad guys are just robots, then the good guys are, too.

Published on April 19, 2012 03:40

April 13, 2012

Herculaneum

Herculaneum is the best-preserved of all classical sites--at least, if there is a better-preserved site, I don't know about it. (If someone out there does, please, tell me! I'll get there ASAP, camera at the ready!) Look at that ceiling! Probably you can't make them out, but the impluvium is ringed witha decoration of little bronze dog-heads. Look at the remains of the paintwork; look at the wooden partition, charred but intact, which once screened off the back of the courtyard! Where Pompeii was buried in ash and debris, which collapsed the roofs of its buildings, Herculaneum was encased in hot mud-flows, which set like concrete, preserving the city as it was in the moment Vesuvius erupted--even to the price of different sorts of wine.

Herculaneum is the best-preserved of all classical sites--at least, if there is a better-preserved site, I don't know about it. (If someone out there does, please, tell me! I'll get there ASAP, camera at the ready!) Look at that ceiling! Probably you can't make them out, but the impluvium is ringed witha decoration of little bronze dog-heads. Look at the remains of the paintwork; look at the wooden partition, charred but intact, which once screened off the back of the courtyard! Where Pompeii was buried in ash and debris, which collapsed the roofs of its buildings, Herculaneum was encased in hot mud-flows, which set like concrete, preserving the city as it was in the moment Vesuvius erupted--even to the price of different sorts of wine.

It is, therefore, a bit odd that Herculaneum tends to be treated as Pompeii's poor relation. It's true that it isn't as big. In Pompeii you can wander for miles; in Herculaneum you're confined to about sixteen city blocks, since that's all that's been excavated. Sixteen blocks, though, is about as much as any normal tourist can cope with at one go, and there's more to see in a smaller area, so you'd think tour companies would prefer it. You'd think, too, that the modern town of Ercolano would view it as a gold-mine, and be proud of it. There is so much continuity. Looked at from across the ruins, the modern and ancient towns seem to blend together.

Alas, modern Ercolano has little interest in ancient Herculaneum. Arrive at the city on the Circumvesuviana railroad--the most convenient way of getting there from Naples or the Sorrentine Peninsula--and you will not find a single sign to direct you to the ruins--which are only about a ten minute's walk away down a hill. When I visited with my mother, she could not find a single shop or kiosk in the town which stocked postcards; she was so annoyed that she went and complained to the tourist office--which didn't have any postcards, either. A local volunteer, who happened to overhear her complaint, lamented the attitude of the town authorities--he said he had regularly complained about boys playing football in the fragile ruins, but nobody had taken any action to protect them. He, like the guards we met on the site, was knowledgeable and enthusiastic, but one sensed he was close to despair over the attitude of his fellow-citizens.

My mother was trying to buy her postcards in the town because the shop at the archaeological site was closed. So was the onsite museum. So were many of the best buildings in the town. The suburban baths, which I visited the last time I was in Herculaneum, were closed as unsafe and propped up with scaffolding--that was where they found the bodies of the ancient dead, a very moving and evocative place. There were numerous placards about the site entrance referring to the money donated by (mostly American and British) foundations for conserving the site, but there was not, actually, much to show for their efforts, and one did wonder whether the money was being siphoned off. The problems the Neapolitan region has with corruption are, of course, notorious.

The House of the Gladiators at Pompeii collapsed last year after heavy rains, and many other buildings, there, in Herculaneum, and throughout the rest of Italy are threatened with the same fate. Sufficient funds for conservation weren't provided by the previous government, and it's unlikely that the present austerity government will be more generous. My advice to any one who hasn't seen Pompeii or Herculaneum has to be, go now.

Published on April 13, 2012 04:57

April 1, 2012

Museo Nazionale Romano

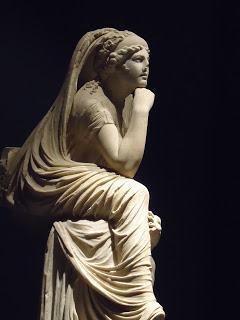

Stunning, isn't she? She's a sea-goddess, 1st C. AD, and she's in the Palazzo Massimo of the Museo Nazionale Romano. The Museo Nazionale should have been on my A-list for things to see in Rome, but, misled by guidebooks (which are always insufficiently impressed by Roman stuff) I'd put it at the top of the 'B' list instead. I hasten to add, however, that it's a museum I've long been eager to visit, but haven't been able to before: it was closed for renovations. (Well, most of it. I did get to the epigraphy section, which had some really neat stuff--but classical inscriptions are, admittedly, a minority taste.)

Stunning, isn't she? She's a sea-goddess, 1st C. AD, and she's in the Palazzo Massimo of the Museo Nazionale Romano. The Museo Nazionale should have been on my A-list for things to see in Rome, but, misled by guidebooks (which are always insufficiently impressed by Roman stuff) I'd put it at the top of the 'B' list instead. I hasten to add, however, that it's a museum I've long been eager to visit, but haven't been able to before: it was closed for renovations. (Well, most of it. I did get to the epigraphy section, which had some really neat stuff--but classical inscriptions are, admittedly, a minority taste.)The renovations are a success, but the museum as a whole is still a mess. It's spread out over four or five different sites, some of which are still closed; the building which is prominently labelled 'MUSEO NAZIONALE' is not, in fact, the main one, but there's nothing to tell you this on the entrance, and buying a ticket does not entitle you to a plan showing you where the rest of the museum is. Even when you find the Palazzo Massimo there's nothing at the entrance to tell you what is where. Luckily, I knew what I wanted to see, and immediately asked the guards where I could find the frescoes from the domus Liviae.

They were on the second floor. Keeping them company were a host of other Roman frescoes and mosaics.

It was not quite the best collection of ancient painting I've ever seen--I'd give that honour to the Archaeological Museum in Naples, which has the pick of Pompeii and Herculaneum--but it was very, very good. I had it all to myself, too: in the forty minutes or so I spent there I encountered only one other visitor.

The lovely sea-goddess was on the first floor, and similarly ignored. The ground floor, however, was busier. I can only guess that the tourists didn't know there was more to see upstairs.

Museums in Italy (and in Greece and Turkey, for that matter) often do seem rather to frown upon tourists, in a way that to someone from the north of Europe seems downright bizarre. Enter even a regional museum in England and you'll be confronted with a shop and a cafe; you'll have multi-lingual audio-guides thrust at you; there will be a 'childrens' trail' and a list of events. Italian museums, in contrast, make a point of hiding even the lift: ask for it, and a member of staff will escort you through two closed rooms to a broom cupboard. Frequently the museums are closed altogether, for long periods of time. (The one in Herculaneum, for example.) I suspect that English museums get to keep the profits from their shops, cafes, and events, to defray their costs, and that Italian ones don't.

Published on April 01, 2012 07:00

March 9, 2012

Italy

I will not be writing this blog next week. I am off to Italy for a week, setting out on Tuesday.

I will not be writing this blog next week. I am off to Italy for a week, setting out on Tuesday.I've been before, of course--as a classicist, how could I not? After four visits to Rome I still haven't managed to go to all the things on my top-ten A-list. I doubt I'll manage them this time, either: we're only in Rome for a day, this time, not long enough to hit Hadrian's villa, and as for the Via Appia Antica, one really has to do that on a Sunday, when it's closed to traffic.

The impetus for this visit is my 83-year-old mother, who has lost none of her wanderlust with age. In a casual chat she lamented the fact that she had never seen Florence or the Bay of Naples, and it didn't seem to me that there was any reason for her to put up with that situation.

I've been to Florence three times. I remember the first occasion most vividly: I drove there with my fiance--as he was then--on a holiday from Paris, where we were living at the time. I left the car parked in a row with other cars, and returned awash with the glories of the Renaissance to find that the whole row of motors had been towed away. (The police were very understanding of our foreign stupidity, and let us off the parking fine, though we still had to pay the tow charge.)

The Renaissance is not really my period, though Florence is hard to resist. I'll feel more at home, though, in the Bay of Naples. I've been to Pompeii and Herculaneum before, too--twice--but I can't imagine getting tired of them. On my first visit I was too excited even to take pictures, and grinned so hard that at the end of the day my whole face ached. I was calmer second time around, but no less enchanted.

Picnicin Herculaneum

We wandered through the ruins marvellingat frescoed ceilings, bowls of paintedfruit,medusa-headed fountains and mosaic floors--then settled in a garden where we atesalami sandwiches on benches in the shade.Beyond us stood the bath-house where theyfoundthe huddled bones of the all the city'sdead.Vesuvius rose above us, hazed with blue.In the garden, pomegranates grew.

The men and women who resided herelike us, and like Demeter's daughter, knewthat fruit:the tree that loves the water, loves thesun;the biting sweetness of its seed upon thetongueand taste that binds to death when dark hascome.

Published on March 09, 2012 04:56

March 1, 2012

World Book Day

As an author I feel obliged to take note of the first of March, though I know that no comment I could make will be half as impressive as the celebrations at my grandson's school, where the children are arriving dressed as their favourite fictional characters. (I mean, really, what words can compete with the faces of a lot of excited four- and five- year-olds?) Still, the occasion offers a chance to reflect on the craft which has engaged me all my life.

Like most authors, I read a lot, at least when I'm not writing myself. (I'm supposed to be writing now, but the latest book is stuck--again--so I've been giving it a break and loading up the Kindle.) I enjoy books of many different types: literary fiction, science fiction and fantasy, murder mysteries, popular science, poetry--everything, really, except romances, which I just don't get. (They seem to me nothing but improbable obstacles to an inevitable outcome.)

When it comes to style, though, I can't seem to arrive at any conclusions about what I like. I know what my principles are when I'm writing. Never use a long word unless it really adds something that isn't there in the short one; never use a Latin word when an Anglo-Saxon one will do; whenever possible use a verb instead of an adverb, a noun instead of an adjective; look for ways to cut, rather than expand, descriptions; if a metaphor feels strained dump it, and so on. When I'm reading, though, I'm inconsistent. I condemn some books (high-brow and low-) as over-written, word-heavy, too elaborate. Persicos odi, puer, apparatus! as the poet Horaces says, 'Boy, I hate these Persian gewgaws, these interwoven crowns can never please me.' I recently read Carol Birch's Jamrach's Menagerie; after the first chapter I found the dense, vivid language wearing, and by the end I was skimming paragraphs, only stopping to read them through if it looked as though something was actually happening. How much better, I thought, was the limpid prose of, e.g., Andrew Miller's Pure, everything in its place and every nuance counting! Yes, I told myself, simple, clear prose really is better . . .then I remembered how much I love the verbal extravagance and inventiveness of Neal Stephenson or Michael Chabon. I certainly can't claim them for the simple and limpid school, but I absolutely love the way they write.

I'm on firmer ground with fiction's other ingredients. I like it when characters have distinctive voices, so that you know who's talking before you reach the 'X said'. I like characters who aren't too simple, and I like to be shown, rather than told, what they're like. I like books that have a plot--not necessarily an action-packed one, but there should be a conflict which is resolved somehow at the end. I don't like epics; I want what I read to have a beginning, a middle and an end--but that's a matter of taste, not an aesthetic judgement.

There are times when being an author myself prevents me from enjoying something I otherwise might. This happens most often when there are holes in the logic of a plot. I try very hard to avoid these when I'm writing, with the result that I notice them at once when I read them. No, I think, the timing doesn't work; or Why does she think that? Nobody would think that! or Why the hell does the bad guy bother?What's in it for him?--and then I can't read any more of an otherwise entertaining author. There are other times, though, when being an author myself means I enjoy something most people miss. Patrick O'Brian, for example, had a mastery of narrative which was extraordinary: he could make time speed up or slow down, move from breathless action to long weeks of calm without jarring; convey details in dialogue or slip into first-person narration through journals and letters without once slowing the momentum of the book--all without calling attention to himself. That's real writing.

Like most authors, I read a lot, at least when I'm not writing myself. (I'm supposed to be writing now, but the latest book is stuck--again--so I've been giving it a break and loading up the Kindle.) I enjoy books of many different types: literary fiction, science fiction and fantasy, murder mysteries, popular science, poetry--everything, really, except romances, which I just don't get. (They seem to me nothing but improbable obstacles to an inevitable outcome.)

When it comes to style, though, I can't seem to arrive at any conclusions about what I like. I know what my principles are when I'm writing. Never use a long word unless it really adds something that isn't there in the short one; never use a Latin word when an Anglo-Saxon one will do; whenever possible use a verb instead of an adverb, a noun instead of an adjective; look for ways to cut, rather than expand, descriptions; if a metaphor feels strained dump it, and so on. When I'm reading, though, I'm inconsistent. I condemn some books (high-brow and low-) as over-written, word-heavy, too elaborate. Persicos odi, puer, apparatus! as the poet Horaces says, 'Boy, I hate these Persian gewgaws, these interwoven crowns can never please me.' I recently read Carol Birch's Jamrach's Menagerie; after the first chapter I found the dense, vivid language wearing, and by the end I was skimming paragraphs, only stopping to read them through if it looked as though something was actually happening. How much better, I thought, was the limpid prose of, e.g., Andrew Miller's Pure, everything in its place and every nuance counting! Yes, I told myself, simple, clear prose really is better . . .then I remembered how much I love the verbal extravagance and inventiveness of Neal Stephenson or Michael Chabon. I certainly can't claim them for the simple and limpid school, but I absolutely love the way they write.

I'm on firmer ground with fiction's other ingredients. I like it when characters have distinctive voices, so that you know who's talking before you reach the 'X said'. I like characters who aren't too simple, and I like to be shown, rather than told, what they're like. I like books that have a plot--not necessarily an action-packed one, but there should be a conflict which is resolved somehow at the end. I don't like epics; I want what I read to have a beginning, a middle and an end--but that's a matter of taste, not an aesthetic judgement.

There are times when being an author myself prevents me from enjoying something I otherwise might. This happens most often when there are holes in the logic of a plot. I try very hard to avoid these when I'm writing, with the result that I notice them at once when I read them. No, I think, the timing doesn't work; or Why does she think that? Nobody would think that! or Why the hell does the bad guy bother?What's in it for him?--and then I can't read any more of an otherwise entertaining author. There are other times, though, when being an author myself means I enjoy something most people miss. Patrick O'Brian, for example, had a mastery of narrative which was extraordinary: he could make time speed up or slow down, move from breathless action to long weeks of calm without jarring; convey details in dialogue or slip into first-person narration through journals and letters without once slowing the momentum of the book--all without calling attention to himself. That's real writing.

Published on March 01, 2012 04:19

Gillian Bradshaw's Blog

- Gillian Bradshaw's profile

- 320 followers

Gillian Bradshaw isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.