Stephen W. Hiemstra's Blog, page 24

January 26, 2025

Oración de Amor Dinámica

Por Stephen W. Hiemstra

Bendito Señor Jesús,

Toda la gloria y el honor, el poder y el dominio, la verdad y la justicia son tuyos, porque pacientemente nos amaste, nos enseñaste la reconciliación, nos ofreciste restauración y nos protegiste a medida que crecíamos hasta la madurez.

Perdona nuestros corazones errantes, nuestros pensamientos desenfrenados, y nuestros deseos maliciosos. Confesamos que no merecemos tus afecciones.

Gracias por tu misericordia en la cruz, perdonando nuestros pecados mientras éramos indiferentes a ti y a quienes nos rodean.

En el poder de tu Espíritu Santo, atráenos hacia ti. Abre nuestros corazones, ilumina nuestros pensamientos y fortalece nuestras manos en tu servicio.

En el nombre del Padre, del Hijo y del Espíritu Santo, Amén.

Oración de Amor Dinámica

Also see:

El Rostro de Dios en las Parábolas

Prefacio de La Guía Cristiana a la Espiritualidad

Prefacio de la Vida en Tensión

The Who Question

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_25, Signup

The post Oración de Amor Dinámica appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

January 24, 2025

Applying Love

Know therefore that the LORD your God is God,

the faithful God who keeps covenant

and steadfast love with those who love him

and keep his commandments, to a thousand generations,

and repays to their face those who hate him,

by destroying them.

(Deut 7:9-10)

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

In the parables examined, we begin to see the many facets of God’s love.

Jesus introduces the Parable of the Good Samaritan to address the problem with interpreting God’s love. When the Samaritan stops to attend to the wounds of the man beaten by robbers, it is an example presumably of offering love to an enemy, because the man beaten is presumed to have been a Jew and Jews hated Samaritans (Matt 5:43-46). More than this, there is also an echo of the story of Cain and Abel (Gen 4) in the parable because Samaritans and Jews can be thought of as estranged brothers—the Northern and Southern Kingdoms of Israel—who have been reunited in love (1 Kgs 12). The parable thus offers love as an allegorical reconciliation of the long-divided, Davidic Kingdom.

If the Parable of the Good Samaritan shows love as a conduit to reconciliation, the Parable of the Two Brothers displays love as a catalyst for adolescent growth and maturity in a context reminiscent of God’s request of Abraham: “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you.” (Gen. 12:1). This reality of God’s love is captured in the adage: God don’t so much care what you do as the person you become. Where we might see criminal justice, God is more interested in restorative justice where, like Jesus with the woman caught in adultery, focused on the person she could be, not the person she had been (John 8:10-11).

Note that in these two parables, love is not a static description of adoration so much as a dynamic strategy for growth, reconciliation, and restoration. Furthermore, the love of the father for the prodigal son multiples the love than the son displays. This is not a transactional love between two narcissists, but a transformative love that, like the Parable of the Friend at Midnight and enemy love, which comes at a cost and is never convenient. Getting out of bed at midnight to offer hospitality to a neighbor in need is never convenient. One never counts one’s change with family and friends, and it is best not to grumble about it.

The reckless love of the Shepherd for the Lost Sheep is most meaningful when we realize that we are all lost sheep. The dichotomous world of good and bad fish illustrated in the Parable of the Dragnet highlights the cost of such reckless love and serves to shock us out of complacency. Do we turn to God in our pain or sulk in our grief? Over time Gethsemane moments move from a decision, to a habit, to a lifestyle and define the person we become and the culture we engender. The reckless love of God more than the threat of judgment gives us a reason to turn to God in our pain.

In Christ, love is an open-handed affection with an eye on the future.

Applying Love

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_25, Signup

The post Applying Love appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

Aplicando Amor

Reconoce, pues, que el SEÑOR tu Dios es Dios, el Dios fiel,

que guarda Su pacto y Su misericordia hasta mil generaciones

con aquéllos que Lo aman y guardan Sus mandamientos;

pero al que Lo odia, le da el pago en su misma cara, destruyéndolo;

y no se tarda en castigar al que Lo odia, en su misma cara le dará el pago.

(Deut 7:9–10)

Por Stephen W. Hiemstra

En las parábolas examinadas, comenzamos a ver que el amor de Dios tiene muchas facetas.

Jesús presenta la Parábola del Buen Samaritano para abordar el problema de interpretar el amor de Dios. Cuando el samaritano se detiene para atender las heridas del hombre golpeado por los ladrones, es un ejemplo de ofrecer amor a un enemigo, porque se presume que el hombre golpeado era judío y los judíos odiaban a los samaritanos (Mateo 5:43–46). Más que esto, también hay un eco de la historia de Caín y Abel (Gén 4) en la parábola. Se puede considerar a los samaritanos y a los judíos como hermanos distanciados—los reinos del norte y del sur de Israel—que se han reunido en el amor (1 Kg 12). Así, la parábola describe el amor alegóricamente como la reconciliación del Reino Davídico, dividido durante mucho tiempo, bajo el paraguas del amor de Dios.

Si la parábola del buen samaritano muestra el amor como un conducto hacia la reconciliación, la parábola de los dos hermanos muestra el amor como un catalizador para el crecimiento y la madurez de la adolescencia. Esta idea recuerda la petición de Dios a Abraham: ¨Vete de tu tierra, De entre tus parientes Y de la casa de tu padre, A la tierra que Yo te mostraré.¨ (Gen 12:1)

Esta realidad del amor de Dios se refleja en el dicho: A Dios no le importa tanto lo que haces sino la persona en la que te conviertes. Donde podríamos imaginar un contexto de justicia penal, Dios está más interesado en la justicia restaurativa que, como Jesús con la mujer sorprendida en adulterio, se centró prolépticamente en la persona que ella podría ser, no en la persona que había sido (Campbell 2010, 11–12).

En estas dos parábolas, el amor no es tanto una descripción estática de la adoración como una estrategia dinámica para el crecimiento, la reconciliación y la restauración. Además, el amor del padre por el hijo pródigo multiplica el amor que muestra el hijo. Este no es un amor transaccional entre dos narcisistas, sino un amor transformador que, como la parábola del amigo a medianoche y el amor enemigo, tiene un costo y nunca es conveniente. Levantarse de la cama a medianoche para ofrecer hospitalidad a un prójimo necesitado nunca es conveniente.

El amor imprudente del Pastor por la oveja perdida es más significativo cuando nos damos cuenta de que todos somos ovejas perdidas. El mundo dicotómico de los peces buenos y malos ilustrado en la parábola de la draga resalta el costo de un amor tan imprudente y sirve para sacarnos de la complacencia. ¿Recurrimos a Dios en nuestro dolor o nos enfurruñamos en nuestro dolor? Con el tiempo, los momentos de Getsemaní pasan de una decisión a un hábito y a un estilo de vida que define la persona en la que nos convertimos y la cultura que engendramos. El amor imprudente de Dios es más que la amenaza de juicio que nos da una razón para volvernos a Dios en nuestro dolor.

En Cristo, el amor es un afecto de manos abiertas con la mirada puesta en el futuro y en la persona en la que nos convertimos.

Aplicando Amor

Also see:

Prefacio de La Guía Cristiana a la Espiritualidad

Prefacio de la Vida en Tensión

The Who Question

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_25, Signup

The post Aplicando Amor appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

January 21, 2025

Peterson Writes About Pastoral Life

Eugene H. Peterson. 2011. The Pastor: A Memoir. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

Eugene H. Peterson. 2011. The Pastor: A Memoir. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

Review by Stephen W. Hiemstra

One of the most dramatic appearances of God in the Bible comes in chapter 3 of Exodus when God appears to Moses in form of a burning bush. It is interesting to ask why God would appear in the form of a naturally occurring inkblot test. If the inkblots are properly prepared, they have no inherent structure so when a patient looks at them, the only structure seen is the structure imposed by the patient. Is it any wonder that my kids, when they were small, used to confuse our pastor with Jesus? My kids are not the only ones; the inkblot image is a wonderful metaphor for how people today relate to their pastor and to God. The more enigmatic the pastor, the more fitting the inkblot image.

IntroductionIn his memoir, The Pastor, Eugene Peterson captures this enigmatic character[3] when he writes:

“I can’t imagine now not being a pastor. I was a pastor long before I knew I was a pastor; I just never had a name for it. Once the name arrived, all kinds of things, seemingly random experiences and memories, gradually began to take a form that was congruent with who I was becoming, like finding a glove that fit my hand perfectly—a calling, a fusion of all the pieces of my life, a vocation: Pastor.” (2)

Peterson see the pastor as a particularly talented observer, much like God took animals to Adam to see what he would call them (Gen 2:19), as he writes:

“A witness is never the center, but only the person who points to or names what is going on at the center—in this case, the action and revelation of God in all the operations of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.” (6)

But, of course, naming is the creative act of a sovereign, not of a passive observer. For this reason, some theologians describe God as a Suzerain (King of Kings) and Adam as his Vassal (king), but Peterson would chide at the whole idea of being an authority figure, preferring the title of pastor, not “Reverend or Doctor or Minister” (2) even though he was all of these things.

Even if Peterson prefers business causal, he is not just causally present. He writes:

“Staying alert to these place and time conditions—this topos, this kairos—of my life as a pastor, turned out to be more demanding than I thought it would.” (8)

Peterson’s sensitive to matters of time and space comes as a surprise. As Christians, we think of God in terms of the omnis—omnipresent, omniscient, omnipotent—all present, all knowing, and all powerful; but Christianity has no Mecca where we must worship or make a pilgrimage—God is not partial to a particular place and even Sabbath is not so much a day as a commitment to devote time to God. But for Peterson pastors must model themselves on God in his omnis in a sacramental sense: “For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for the ungodly.” (Rom 5:6 ESV) And Christ did not die in some random place; he died conspicuously—in front of the whole world—in Jerusalem. Therefore, Peterson cautions that “the life of faith cannot be lived in general or by abstractions.” (12)

Do you get the idea that Peterson chooses his words carefully?

Peterson’s idea of the pastor call is wrapped up in a peculiar package. He describes a dog wandering around marking his territory in a manner that appears haphazardly to a human observer, but no doubt makes perfect sense to the dog. He then writes:

“Something like that is the way pastor feels to me. Pastor: not something added on to or imposed on who I am; it was there all along. But it was not linear—no straight-line development.” (26)

This sort of explanation, which is potentially quite demeaning, describes an image of the pastor as a Myers-Briggs personality type of ESFP:

“Outgoing, friendly, and accepting. Exuberant lovers of life, people, and material comforts. Enjoy working with others to make things happen. Bring common sense and a realistic approach to their work, and make work fun. Flexible and spontaneous, adapt readily to new people and environments. Learn best by trying a new skill with other people.”

This postmodern concept of a pastor leaves me wondering what would happen if Martin Luther or John Calvin were to come before an ordination committee today? While I know that Peterson’s pastor has great appeal today, I am not sure that Peterson intended his vision of the pastor to be normative, as it has become.

One of the attractive things about Peterson to me as I read this book in seminary was that he had been a church planter. At a time when organized churches seem to be wandering off the rails, God’s presence appears most conspicuously in new churches that have yet to be coopted by our culture. Peterson writes about an old rabbinic story:

“Shekinah is Hebrew word that refers to a collective vision that brings together dispersed fragments of divinity. It is usually understood as a light-disseminating presence bringing an awareness of God to a time and place where God is not expected to be—a place…God’s personal presence—and filled that humble, modest, makeshift, sorry excuse for a temple with glory.” (100-101).

I can relate to this Shekinah image, having worshipped in so many different places, in so many different styles of music (or none at all), and in so many different languages.

Peterson’s final chapters begin with a story of a visit to a monastery where the cemetery was always prepared for the next funeral, having an open grave as a reminder (289). This is fitting end because Christianity is the only religion that began in a cemetery (Matt 28:1-7). Citing Karl Barth, Peterson reminds us: “Only where graves are is there resurrection.” (290).

AssessmentI have tried several times to review Eugene Peterson’s book, The Pastor, and flinched at the task, not knowing where to begin. Having written my own memoir, however, during the past year, his book started to make sense to me in spite of its nonlinearity. I think that I have read most of Peterson’s books, but this is a favorite, but do not ask me why. Still, I am sure that most pastors and seminary students will share my love for this book.

FootnotesWhat does Moses see? Moses sees God commanding him to return to Egypt and ask Pharaoh to release the people of Israel, something that had been on his heart for about 40 years (Exod 2:11-12; 3:10).

This is at the heart of the psychiatric image of God and counseling model of the pastor. People have a lot of trouble with the transcendence of God. They do not want to be “fathered” with conditional love, they wanted to be “mothered” with unconditional love. For this reason, the postmodern image of God is more of a grandparent than a parent and people chide at the ideal that God is a father that actually requires anything at all of us. The code language normally used is to say that a pastor should be a “patient, non-anxious presence.”

[3] If you think that I am the only one to see an inkblot here, meditate a few minutes on Peterson’s book cover.

http://www.MyersBriggs.org/my-mbti-pe....

Peterson Writes About Pastoral LifeAlso see:Niebuhr Examines American Christian Roots, Part 1 Friedman Brings Healing by Shifting Focus from Individuals to the Family Books, Films, and MinistryOther ways to engage online:Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.netPublisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_25, Signup

The post Peterson Writes About Pastoral Life appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

January 20, 2025

Dragnet: Monday Monologues (podcast), January 20, 2025

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

This morning I will share a prayer and reflect on the Parable of the Dragnet. After listening, please click here to take a brief listener survey (10 questions).

To listen, click on this link.

Hear the words; Walk the steps; Experience the joy!

Dragnet: Monday Monologues (podcast), January 20, 2025

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_25, Signup

The post Dragnet: Monday Monologues (podcast), January 20, 2025 appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

January 19, 2025

Prayer before the Dragnet

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

Almighty Father,

All glory and honor, power and dominion, truth and justice are yours, because you lived a sinless life, died on the cross for our sins, and rose from the dead that we might have the hope of eternal life. In whom else shall we believe?

Forgive our besetting sins, the ones so close to our hearts that we repeat them over and over. We confess that we love our sins and can only be rid of them with your forbearance and assistance. In whom else shall we believe?

Thank you for our families, our health, our means of support, and our salvation in you. Thank you for the opportunity to minister to others and expand your holy kingdom. In whom else shall we believe?

In the power of your Holy Spirit, grant us strength to live each day, the grace to witness to those around us, and the peace that passes all understanding, your shalom. Draw us to you—Open our hearts, illumine our thoughts, and strengthen our hands in your service.

In Jesus’s precious name, Amen.

Prayer before the Dragnet

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_25, Signup

The post Prayer before the Dragnet appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

Oración ante la Red de Arrastre

Por Stephen W. Hiemstra

Padre Todopoderoso,

Toda la gloria y el honor, el poder y el dominio, la verdad y la justicia son tuyos, porque Jesús vivió una vida sin pecado, murió en la cruz por nuestros pecados y resucitó de entre los muertos para que podamos tener la esperanza de la vida eterna. ¿En quién más creeremos?

Perdona nuestros pecados que nos acosan, aquellos que están tan cerca de nuestro corazón que los repetimos una y otra vez. Confesamos que amamos nuestros pecados y sólo podemos deshacernos de ellos con tu paciencia y ayuda. En quienes deberíamos creer? ¿En quién más creeremos?

Gracias por nuestras familias, nuestra salud, nuestros medios de sustento y nuestra salvación en ti. Gracias por la oportunidad de ministrar a otros y expandir tu santo reino. ¿En quién más creeremos?

En el poder de tu Espíritu Santo, concédenos la fuerza para vivir cada día, la gracia para dar testimonio a quienes nos rodean y la paz que sobrepasa todo entendimiento, tu shalom. Atráenos hacia ti: abre nuestros corazones, ilumina nuestros pensamientos y fortalece nuestras manos en tu servicio.

En el precioso nombre de Jesús, Amén.

Oración ante la Red de Arrastre

Also see:

El Rostro de Dios en las Parábolas

Prefacio de La Guía Cristiana a la Espiritualidad

Prefacio de la Vida en Tensión

The Who Question

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_25, Signup

The post Oración ante la Red de Arrastre appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

January 17, 2025

The Dragnet

What man of you, having a hundred sheep, if he has lost one of them,

does not leave the ninety-nine in the open country,

and go after the one that is lost, until he finds it?

(Luke 15:4)

By Stephen W. Hiemstra

No survey of love in the parables is complete without an examination of the Parable of the Lost Sheep. While the parable clearly exhibits God’s grace, as already mentioned, it is hard to isolate this grace from hesed love. There is an implicit bond, a covenant of care, between a shepherd and the sheep—ownership implies care. Even in the case of a superpower there is an obligation to protect its weaker allies, like a mother cares for her child or a duck for her ducklings.

Still, several aspects of the Parable of the Lost Sheep are unsettling in its presentation of love, starting with the word, lost. The word, lost, in the Greek (ἀπόλλυμι, BDAG 958) can mean: “1. to cause or experience destruction; 2. to fail to obtain what one expects or anticipates, lose out on, lose; or 3. to lose something that one already has or be separated from a normal connection, lose, be lost.” How did this sheep get lost and who is responsible? Why does the shepherd leave the other ninety-nine sheep unattended while he searches for the lost sheep? It appears that the value placed on the lost sheep is imprudent, even reckless.

When we take the next step and apply this parable to sinners, this parable becomes even more awkward. Does God love sinners more than the faithful? The righteous seem to get a bum rap in this parable. Actually, the cheeky nature of this parable is the main point: We are all sinners; none are righteous; all have fallen short of the love of God. This parable makes no sense without the doctrine of original sin. The ninety-nine righteous people are an illusion—none are righteous (Luke 18:18-19). We are all lost sheep. Blomberg (2012, 216) observes that many interpret “righteous” to imply more like “self-righteous,” which speaks to a problem of religious complacency. No one wants to be seen as lost.

The Dragnet

The need for vigilance among the faithful is reinforced by the many parables focusing on judgment, like the Parable of the Dragnet. Here we read:

Again, the kingdom of heaven is like a net that was thrown into the sea and gathered fish of every kind. When it was full, men drew it ashore and sat down and sorted the good into containers but threw away the bad. So it will be at the end of the age. The angels will come out and separate the evil from the righteous and throw them into the fiery furnace. In that place there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. (Matt. 13:47-50)

Judgment makes the point that its hard for God to love the good (righteous) if he doesn’t hate the bad (evil).

This dichotomous world of good and bad fish pictured bothers most Christians today because they reject moralistic thinking. For a first-century Jew, the picture here is of righteous people who obey the Mosaic covenant and unrighteous who do not. In the parable, the sorting of good and bad is initially done by the fishermen, who keep the good and recycle the bad. Later, these fishermen are described as angels who throw the evil into the fiery furnace without saying what becomes of the righteous.

I find it helpful to recast the dichotomous picture here as our response to pain during a Gethsemane moment. When we face a painful moment or a painful choice, do we turn to God and give it over to him or do we turn into the pain and sulk? (Matt 26:39) When we habitually do one or the other, our personalities and culture are formed and hardened. The Dragnet also suddenly becomes real, although judgment is something we impose on ourselves, not something imposed by God.

The Good News is that Christ died for our sins so we don’t have to.

The Dragnet

Also see:

The Face of God in the Parables

The Who Question

Preface to a Life in Tension

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_25, Signup

The post The Dragnet appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

Red de Arrastre

¿Qué hombre de ustedes, si tiene cien ovejas y una de ellas se pierde,

no deja las noventa y nueve en el campo

y va tras la que está perdida hasta que la halla?

(Lucas 15:4)

Por Stephen W. Hiemstra

Ningún estudio del amor en las parábolas está completo sin un examen de la Parábola de la Oveja Perdida. Si bien la parábola muestra claramente la gracia de Dios, como ya se mencionó, es difícil aislar esta gracia del amor hesed. Hay un vínculo implícito, un pacto de cuidado, entre un pastor y las ovejas—la propiedad implica cuidado. Incluso una superpotencia reconoce la obligación de proteger a sus aliados más débiles, como una madre cuida de su hijo o un pato de sus patitos.

Aun así, varios aspectos de la parábola de la oveja perdida son inquietantes en su presentación del amor, empezando por la palabra perdida. La palabra perdido, en griego apollymi (BDAG 958) puede significar: “1. causar o experimentar destrucción; 2. no obtener lo que se espera o anticipa, perder; o 3. perder algo que ya se tiene o separarse de una conexión normal, perder, estar perdido.” ¿Cómo se perdió esta oveja y quién es el responsable? ¿Por qué el pastor deja desatendidas a las otras noventa y nueve ovejas mientras busca a la oveja perdida? Parece que el valor que se da a la oveja perdida es imprudente, incluso temerario.

Cuando damos el siguiente paso y aplicamos esta parábola a los pecadores, se vuelve aún más incómoda. ¿Ama Dios a los pecadores más que a los fieles? Los justos parecen tener mal tratamiento en esta parábola. En realidad, la naturaleza audaz de esta parábola es el punto principal: Todos somos pecadores; ninguno es justo; todos están destituidos de la gloria de Dios. Esta parábola no tiene sentido sin la doctrina del pecado original (Sal 14). Los noventa y nueve justos son una ilusión: ninguno es justo (Lucas 18:18–19). Todos somos ovejas perdidas. Blomberg (2012, 216) observa que muchos interpretan que “justo” implica más bien “auto-justo,” lo que habla de un problema de complacencia religiosa. Nadie quiere que lo vean perdido.

Red de Arrastre

La necesidad de vigilancia entre los fieles se ve reforzada por las numerosas parábolas que se centran en el juicio, como la Parábola de Red de Arrastre. Aquí leemos:

`El reino de los cielos también es semejante a una red barredera que se echó en el mar, y recogió peces de toda clase. Cuando se llenó, la sacaron a la playa; y se sentaron y recogieron los peces buenos en canastas, pero echaron fuera los malos. Así será en el fin del mundo; los ángeles saldrán, y sacarán a los malos de entre los justos, y los arrojarán en el horno de fuego; allí será el llanto y el crujir de dientes. (Mateo 13:47–50)

El juicio señala que es difícil para Dios amar honestamente a los buenos (los justos) si no odia a los malos (los malvado).

Este mundo dicotómico de peces buenos y malos que se muestra molesta a la mayoría de los cristianos hoy porque rechazan el pensamiento moralista. Para un judío del primer siglo, la imagen aquí es de personas justas que obedecen el pacto mosaico y de injustos que no lo hacen. En la parábola, la clasificación de lo bueno y lo malo la hacen inicialmente los pescadores, quienes se quedan con lo bueno y reciclan lo malo. Más tarde, estos pescadores son descritos como ángeles que arrojan al mal al horno de fuego sin decir qué será de los justos.

Es útil reformular aquí la imagen dicotómica como nuestra respuesta al dolor durante un momento de Getsemaní. Cuando enfrentamos un momento doloroso o una elección dolorosa, ¿nos dirigimos a Dios y se lo entregamos o nos volvemos hacia el dolor y nos enfurruñamos? (Mateo 26:39) Cuando habitualmente hacemos una u otra cosa, nuestra personalidad y nuestra cultura se forman y endurecen.

Lewis (1973, 10–11) describe el infierno como un lugar donde las personas eligen alejarse cada vez más. De la misma manera, el juicio sugerido por la Parabola de la Red de Arrastre es algo que nos imponemos a nosotros mismos, no algo impuesto por Dios.

Las buenas noticias son que Cristo murió por nuestros pecados para que nosotros no tengamos que hacerlo.

Red de Arrastre

Also see:

Prefacio de La Guía Cristiana a la Espiritualidad

Prefacio de la Vida en Tensión

The Who Question

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_25, Signup

The post Red de Arrastre appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.

January 14, 2025

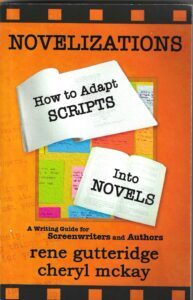

Gutteridge and McKay Turn Scripts into Novels

Rene Gutteridge and Cheryl McKay. 2014. Novelizations: How to Adapt Scripts into Novels. USA: Purple Penworks.

Review by Stephen W. Hiemstra

The idea of adapting a novel from a script sounds like using turning a concert tour into a book. Sure, you can do that, but why? Doesn’t the process usually work the other way around?

Introduction

Rene Gutteridge and Cheryl McKay in their book, Novelizations: How to Adapt Scripts into Novels, write: “Hollywood loves to know they have a built-in audience with whom to start.” (11) The motivation for novelization is simple: It is good marketing. Even scripts that have been produced can get canceled because of the high costs of marketing and distribution. Having a book that already has a large audience is a large plus in assuring that a film project goes forward.

Streaming television shows have to demonstrate that they have an audience of at least ten million to be renewed. Because novelists seldom achieve such an audience, what remains a mystery is how a typical novel could ever make such a contribution. What we learn towards the end of the book is that screenwriters need to partner with established authors in order to meet their audience objective of getting bragging rights from a novelization project. (161)

If the motivation for a novelization project is obvious, how does it actually get done? The objective of this book is to walk the reader through the process of converting a script into a novel. Story, structure, characters, dialogue, and voices require little adjustment, while point of view characters, backstory, interior monologue, and details about setting are areas where changes and additions are needed. (16)

Background and Organization

Rene Gutteridge is a novelist and graduate of Oklahoma City University. Cheryl McKay is a screenwriter and holds a masters from Regent University.

Gutteridge and McKay write in ten chapters:

Overview

Changes & Challenges

Setting

Point of View

Structure & Plot

Interior Monologue

Backstory

Characters

Dialogue & Voices

Partnership (vii)

These chapters are followed with acknowledgments and an about page.

Setting

Screenwriters, unlike novelists, typically work in teams. In the case of settings, whole departments contribute to the scene settings: “The camera department, the production designer, crewmembers who work in locations, art direction, set building, props, wardrobe.” (39) Screenwriters can work painting with broad strokes upfront in a scene to establish the setting where a novelist may need to research and describe every little detail sprinkled throughout a chapter (43).

Point of View

While a script can introduce a quick survey of a character’s life with a montage of visual snippets or display an entire landscape with a drone camera, the same survey in a novel must travel through someone’s head. Point of view requires an observer that may be absent in a script.

Gutteridge makes an interesting observation: “It’s not that he just sees the rocker, but how does he see the rocker? What does he feel when he sees it?” (62) The character in a novel ideally is not a passive observer, but interprets the objects seen. Was the character rocked as a child in the rocker or was a parent shot to death in it?

Structure and Plot

A script typically establishes a scene in location, time, and person. Change any of these and you have a new scene, which makes transitions clear. Consequently, a script may have a lot of short scenes.

Short scenes in a novel are rare. A novel can incorporate such transitions within a given scene or chapter which may lead to sloppy transitions or, depending on the writer, handle such changes seamlessly. (75)

Interior Monologue

A script may need to have a separate scene to reveal backstory and flashbacks, which may easily be handled in a novel with interior monologue. (76) Screenwriters cannot normally employ interior monologue because it cannot be seen and heard on the page (89), which implies that novelizations need to pen that into the novel. (89) These interior moments need to create conflict, add mystery, advance the plot, reveal motives, or do something else worthwhile given the caveat that interior monologue is telling, not showing—typically a no-no in novel composition. (93-94)

Backstory

In a screenplay, backstory is often cloaked in emotion or some action, not straight up exposition in dialogue, guidance equally good for novel writing. (110) Interior monologue can also be used, as mentioned earlier. Either way, it should advance the plot. (111)

Characters and Dialogue

Characters and dialogue cost money in a screenplay production, but come cheap in novels. This implies that screenplays are parsimonious in both and need to be added during a novelization. Characters added to a novel often require backstory. Dialogue may include subtext that requires explanation in the novel, something handled by actors in a screenplay. The world of the screenplay may need to be fleshed out in the novel, particularly in dialogue. (149)

Assessment

Rene Gutteridge and Cheryl McKay’s Novelizations: How to Adapt Scripts into Novels is a surprisingly helpful book, even if you never novelize a screenplay. Of course, if you plan to novelize your screenplay, start with this book.

Early in your screenwriting career, the difference between a novel and a screenplay may seem fuzzy, little more than an exercise in abbreviation and reformatting in a screenwriting software package. Gutteridge and McKay help mark the boundaries between the two media—especially in their novelization examples—so that the strengths and weaknesses of each become clear. This book is consequently of greatest value to young screenwriters and any novelist attempting to adapt their work for film.

Gutteridge and McKay Turn Scripts into Novels

Also see:

Cahir Dissects Film Adaptation

Seger Adapts Stories into Film

Other ways to engage online:

Author site: http://www.StephenWHiemstra.net

Publisher site: http://www.T2Pneuma.com

Newsletter at: https://bit.ly/Janu_25, Signup

The post Gutteridge and McKay Turn Scripts into Novels appeared first on T2Pneuma.net.