Julia Kelly's Blog, page 22

November 14, 2016

The Governess Was Wild Is Out Now!

Readers, The Governess Was Wild, the third and final book in my Governess series is out at ebook retailers now! Here’s a quick look at the book:

Amazon | Amazon UK | iBooks | Kobo | B&N | Google Play

When Lady Margaret Rawson is caught trying to elope with the thoroughly unsuitable James Lawrence, Lord and Lady Rawson decide it’s time to send their daughter away from the temptations of London. The job of delivering the headstrong girl to the family’s isolated Yorkshire estate naturally falls to her governess, Jane Ephram. It should be an easy task, but with the wild Lady Margaret, nothing ever goes according to plan. To make matters worse, Lord Rawson has made it clear that if anything happens to his daughter along the way, Jane will be dismissed without a letter of reference. When Jane finds Lady Margaret’s inn room empty and the charming Lord Nicholas Hollings’s horse missing one morning, she must embark on an adventure of her own with the devilishly handsome baron. Will Jane and Nicholas find Lady Margaret, the scheming Mr. Lawrence, and the missing horse, or will they discover something else entirely?

For more about how the Governess series came to be, go here. To see who I’d cast as characters in my book, head over to XOXO After Dark for a GIF-filled look.

And to listen to a podcast where I talk all about governesses and why I decided to write the books, check out the XOXO After Dark Cast.

November 7, 2016

The Language of Flowers

I’ve always been fascinated by flowers. Not just the bunches of roses that I get from my local bodega to decorate my apartment. I love the complexity of roses, the endless varieties of lavender, and the usefulness of herbs. Flowers are so much more than a fleeting bit of beauty.

It’s no surprise then that when I learned the Victorians had an entire silent language they gave to flowers, I was fascinated and wanted badly to find a way to incorporate it into a book.

The Governess Was Wanton is a twist on the traditional Cinderella story. Some elements are the same — there’s mistaken identity, a woman who is down on her luck, and an item that’s lost and must be returned by a handsome man — but I decided to flip the story to give the fairy godmother her own happily ever after.

Because I was changing the formula, I also wanted to change up the all-important glass slipper. I decided that instead of Cinderella losing her shoe, my heroine, Mary, loses her handkerchief. But it isn’t just any handkerchief. It’s unique, one of a set of twelve given to Mary by her own governess back when her life was very different. Those twelve handkerchiefs are edged in a pattern of ivy and pink geraniums.

Those flowers aren’t an accident. I chose them because in the Victorian flower language ivy stood for friendship, fidelity, and marriage. Geranium had several meetings but the ones I drew on were gentility and esteem as well as true friendship (this last one applied to oak leaf geranium specifically).

What I enjoyed the most about incorporating these flowers was that they were sort of like the Easter eggs you spot in an episode of Doctor Who. If readers know anything about flower language, it’s a fun little thing to pick up in the story. If not, the flowers were just a pretty embellishment on a handkerchief.

The thing to remember is that authors rarely chose to put something as symbolic as the glass slipper — or in this case the embroidered handkerchief — into their story without thinking a bit about the details.

If you’re interested in reading more about flower language and Victorians there’s a wonderful article from Atlas Obscura all about it. The next time you see a flower pop-up and romance novel maybe you can find some deeper meaning in why the author chose that flower in particular.

October 31, 2016

20 Victorian Romances (Plus a Kindle Fire) Are Up for Grabs

It’s been a busy few weeks (and looks like there are a few more busy ones on the horizon) so I’m going to keep things short today.

It’s been a busy few weeks (and looks like there are a few more busy ones on the horizon) so I’m going to keep things short today.

I’ve got a fun surprise for my readers. More than 20 historical romance authors and I have teamed up to give away a huge collection of novels, PLUS one lucky reader is going to win a Kindle Fire!

I love events like this because readers get to discover new authors that could be the next on their instabuy list — and this one’s even more fun for me because all the authors write Victorian romance.

You can win my novel The Governess Was Wicked, plus all those other books by entering this giveaway: http://bit.ly/victorian-rom

The contest runs until Monday, November 7, so be sure to enter!

Good luck!

October 17, 2016

The Governess Problem

I’ve written a bit here about how I came up with the idea to write about three friends who are all governesses and each find their happily ever after in their own time. What I haven’t talked about is why governesses? The answer is simple: governesses occupied a fascinating space as educated, well-bred ladies who earned a wage but weren’t servants. That status on the fringes of society makes them all the more interesting to write about.

“Marian Hubbard ‘Daisy’ Bell and Elsie May Bell with governess,” 1885, Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Who Was the Victorian Governess?

If you’re only vaguely familiar with who governesses were and what they did, here’s a primer. They were often educated, respectable women who’d fallen on hard times, the daughters of parents who couldn’t afford to keep them at home until they married, or other down-on-their-luck widows armed with a good reputation. These women could make an income by educating the girls of a well-to-do middle- or upper-class families until their charges were married and became the mistresses of their own households.

And intentionally or not, governesses were subversive as hell.

It’s important to remember the context of the time period we’re dealing with here. During Victorian England society was governed by a phenomenon called “the two spheres.”

Convention dictated that men occupied the public sphere and could go off into the world and do things like manage businesses, enter into politics, or work. Women got to stay at home.

“The prevailing ideology regarded the house as a haven, a private domain as opposed to the public sphere of commerce,” writes Elizabeth Langland in her article, “Nobody’s Angels: Domestic Ideology and Middle-Class Women in the Victorian Novel.”

White, straight, cisgender women of the middle and upper classes occupied this “private sphere,” but at the same time their money allowed them to delegate many of the duties that would have traditionally fallen to women. In households that could afford it, you hired a maid-of-all-work, or if you had more money specialized servants like chamber maids, ladies maids, and a cook. Families who could afford it hired a nurse and, for the education of their young girls, a governess.

The Governess as a Sexual Threat

Governesses, by professional necessity, were not married. They lived in their employer’s homes and therefore had an intimate knowledge of a family regardless of whether their actual relationships with the individual members were warm or not.

Even though governesses were a status symbol of a certain degree of wealth and class, they were still looked on with suspicion. Having an unmarried woman in close proximity to a husband or older sons was seen as a direct threat to domestic peace. The historian M. Jeanne Peterson quotes at length from Mary Atkinson Maurice’s Governess Life (1849) in her article “The Victorian Governess: Status Incongruence in Family and Society:”

Frightful instances have been discovered in which she, to which the care of the young has been entrusted, instead of guarding their minds in innocence and purity has become the corruptor—she has been the first to lead and to initiate into sin, to suggest and carry on intrigues, and finally to be the instrument of destroying the peace of families…

Because the governess wasn’t the “traditional” Victorian woman who stayed within the confines of her own home and therefore the private sphere, she was seen as threatening to the very structure that held society in check.

Even more concerning — and surely ridiculous to modern readers — was that Victorian womanhood was wrapped up the idea that the ideal woman was modest and retiring when it came to sex. The accepted model of female sexuality can be most easily seen in the works of the much quoted and undeniably naive Dr. William Acton who believed that that “the majority of women (happily for them) are not very much troubled by sexual feelings of any kind” (The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs, 1857). If a woman lived outside of the bounds of her traditional role, she must be a threatening, oversexualized figure. This is where the governess-as-seducer trope you see with characters like Vanity Fair’s Becky Sharpe gets its bite.

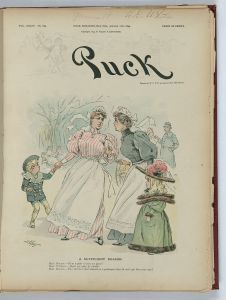

“A sufficient reason,” S.D. Ehrhart, Published by Keppler & Schwarzmann, 1894 January 10, Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

The Governess and The Economic Threat

Governesses didn’t just offend society’s ideas about womanhood because of they lived close to men or their perceived sexuality. They subverted strictly gender roles for middle-class women by earning a wage. This gave the governess access to money, economic independence, and choice — all hallmarks of what we would later come to know as feminism.

Woman in Victorian England had little say over their own money. It wouldn’t be until a series of Married Women’s Property Acts* increased the legal rights of women under British law throughout the 1800s that a woman could inherit and maintain control over her own money within her marriage. Before then she was essentially beholden to first her father and then her husband and sons for the duration of her life. She was essentially a charity case who had little legal recourse if the man who was supposed to be providing for her was instead frittering away her money.

By living outside of the traditional father-daughter or husband-wife structure and earning her own wage, a governess could exercise a degree of independence by having power over her money.

I don’t want to paint too rosy a picture for the Victorian governess. She didn’t earn much money so the independence she did have was limited. “Her working life was not likely to last more than 25 years, at a starting salary of 25l, rarely reaching 80l” (Liza Picard, Victorian London: The Tale of a City, 1840-1870, p. 262).

While teaching was one of the few respectable ways for a middle-class woman to earn her living,** the governess was relegated to a lower social status than her charges. Still, she was earning money and was beholden to no man which meant she had legal control over her income — something married women couldn’t boast of until well into the 19th century.

Making Them Heroines

The conflict built into the governess’s life — whether it’s the perceived threat to the fidelity of a marriage or her uncomfortable limbo between lady and servant — makes her the perfect romance heroine. There’s conflict built into her story from page one because she doesn’t fit neatly into the boxes that Victorian society assigned women. No matter who the hero (or heroine in the case of F/F) is, there is going to be a tension regarding her non-traditional role in the home and in society. And great romance comes out of great tension.

*You can read more about these acts in Mary Lyndon Shanley’s Feminism, Marriage, and Law in Victorian England, a dry but fascinating book.

**Another was writing. Mary Wollstonecraft and Frances Milton Trollope were just two of the women who picked up their pens to earn money during the Georgian and Victorian eras.

Further Reading

Feminism, Marriage, and Law in Victorian England, Mary Lyndon Shanley

“Nobody’s Angels: Domestic Ideology and Middle-Class Women in the Victorian Novel,” Elizabeth Langland

“The Victorian Governess: Status Incongruence in Family and Society,” M. Jeanne Peterson

“Victorian Sexualities,” Holly Furneaux

October 10, 2016

The Governess Was Wanton Is Out Today!

If you read The Governess Was Wicked and thought, “I wish I could read Mary’s story right now,” you’re in luck! The Governess Was Wanton just released today! Here’s a look at what’s in store for the second edition of the Governess series:

Mary Woodward, a young veteran governess, has one job: guiding a young debutante through her first season in high society. And up until now, keeping her focus and avoiding temptation has been easy. But never before has the father of her young charge been as devilishly handsome as the single, wealthy Earl of Asten…. Convinced to risk it all, Mary let’s herself enjoy one night of magic at a masked ball in Asten’s arms, but will they both regret everything when the Earl learns her true identity?

Amazon | Amazon UK | iBooks | Kobo | B&N

I’m already getting great feedback from readers on Goodreads. If you do read the book (or if you read The Governess Was Wicked) I’d really appreciate a review. Reviews help readers figure out what books will and won’t work for them so they’re really important!

The next books in the series, The Governess Was Wild, is still available for preorder and will be coming out in November. Be sure to sign up for my newsletter so you don’t miss any future release dates!

October 3, 2016

Photos: London and The Governess Was Wicked

“This room, with its green-and-white wallpaper and big bay windows looking out over Onslow Square, would continue to be the center of her world until Cassandra was old enough to wear her hair up and marry.” —The Governess Was Wicked

I love books that are strongly grounded in their setting. I want to hear the rush of traffic and feel the breeze from the subway (disgusting though it may be) when I’m reading a book set in New York City. Likewise, if a book takes place during a London winter, I want to know that the characters are chilled to the bone from the damp that sets in around autumn and doesn’t leave until spring.

It was important to me in writing The Governess Was Wicked that readers feel that my characters really do know their way around the parts of Central London that make up their whole world. Here are just a few locations readers will encounter:

The Nortons’ home in Onslow Square in South Kensington with its beautiful, perfectly symmetrical houses.

Dr. Edward Fellows lives in the just-becoming-fashionable neighborhood of Chelsea on Sydney Street where a bachelor doctor could have had his office with rooms above

There’s Mrs. Salver’s Tea Shop in Pimlico, a working class neighborhood where people who served the wealthy in Mayfair and Belgravia would have lived

Elizabeth sends two very important letters from a huge hotel just off Rochester Row near the bustling travel hub of Victoria station

And finally the book ends in Lady Crosby’s Eaton Square home

Since my family lives in this area of London, I asked my father, a talented photographer, to take some photos to show readers a little of the world of The Governess Was Wicked. Enjoy this virtual stroll through the streets!

Click to view slideshow.

September 26, 2016

Lord What? Lady Who? Understanding Titles in Historical Romance

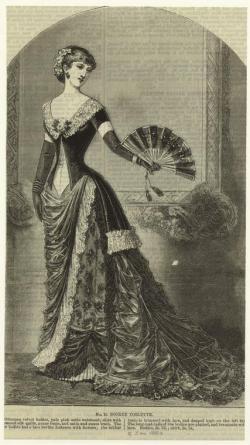

“Soirée toilette.” 1883-01, The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Who cares if Lady Claire, the daughter of the Duke of Rockland, marries Sir Ware, a baron? Her married name will be Lady Ware, and a lady is a lady, right?

Not exactly.

I get a lot of questions about keeping all of those lords and ladies straight in historical romances and why titles matter. It’s complicated in particular because although the peerage has clear rankings (a duke is higher than a marquess, etc.) some people are addressed the same way. This is especially confusing among women.

Here’s a long but hopefully handy guide to telling your barons from your viscounts:

The Royals

Royalty includes the king and queen, the Prince of Wales, any children, and so on. Since I write about Victorian England, the reigning monarch would have been Queen Victoria. Prince Albert was her prince consort (the husband of the queen regent who was not a king himself). The Prince of Wales, the heir apparent, would have been Bertie who then became Edward VII on Victoria’s death.

The Queen

The queen would first have been addressed as Your Majesty on first instance. Then she would be addressed as Ma’am.

Prince Consort, Princes and Princesses of Royal Blood, Dukes and Duchesses of Royal Blood

This group would have included Prince Albert, Victoria’s husband who served as prince consort, the Prince of Wales, and all other royal princes, princesses, and royal dukes and duchesses. They would have been addressed first as Your Royal Highness and then afterward as Sir or Ma’am.

“Presented on the occasion of the coronation of His Majesty King Edward VII, June 26th, 1902.” Cigarette cards, The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

The Peerage

There are five hereditary titles for members of the peerage that are ranked as follows from highest to lowest: duke (duchess), marquess (marchioness), earl (countess), viscount (viscountess), and baron (baroness).

This might all seem straightforward, but it can become confusing and muddled for a few reasons. First of all, in addition to a title, a man or woman would also have a family name. For instance, I might be Julia Kelly, Marchioness of Dunnett. Kelly would be my family name, Dunnett would be my title.

Then there were courtesy titles. If a man was a marquess, he might be Christopher Kelly, Marquess of Dunnett, Earl of Kirk, and so on and so on. He would only be addressed as Lord Dunnett because marquess is his highest ranking title, and his eldest son would be given the courtesy title of Earl of Kirk and would be addressed as Lord Kirk. In the rare cases when there was no second title, the eldest son would be given the family name as a courtesy title (ie Lord Kelly).

There are even more exceptions to the rule, but for now let’s focus on the most common instances.

Dukes and Duchesses

The name of a dukedom is taken from an existing place (ie the Duke of Devonshire). When addressing a duke or duchess, you would call them Your Grace (or referring to them in third person His Grace and Her Grace). My copy of Titles and Forms of Address recommends using titles sparingly in conversation.

The widowed wife of the last duke would would retain her title. However, to differentiate her from the current duchess she would be referred to as the Dowager Duchess and addressed by her first name and then her title. For example, after her husband died in 2004, the Duchess of Devonshire became the Dowager Duchess and was referred to as Deborah, Duchess of Devonshire.

The younger sons of dukes would be called Lord [First name Family name] and the daughters of dukes would be Lady [First name Family name]:

Lord Colin Kelly (addressed in speech as Lord Colin, never Lord Kelly)

Lady Justine Kelly (addressed in speech as Lady Justine, never Lady Kelly)

Marquesses and Marchionesses

Just to make matters complicated, the title of marquess can also be spelled marquis (they may choose how they spell it). The title is generally taken from a place name so one would be the marquess of [place name], although there are four modern exceptions to this rule just to keep things interesting.

A marquess and marchioness would be referred to as Lord and Lady Dunnnett and addressed in speech as My Lord and My Lady. The full formal title of the Marquess of Dunnett would only be used on very formal occasions.

Dowagers marchionesses follow the rule of dowager duchesses.

Younger sons of marquesses are Lord [First name Family name], and rules of address follow the younger sons of dukes.

Younger daughters of marquesses are Lady [First name Family name], and rules of address follow the daughters of dukes.

Earls and Countesses

Some earldoms take a geographical name (which would make the title the Earl of [Place]), some take a family name.

An earl and countess would be referred to as Lord and Lady [Title] and addressed in speech as My Lord and My Lady. As with marquesses and marchionesses their full formal title would only be used on rare formal occasions.

Dowagers countesses follow the rule of dowager duchesses.

Younger sons of marquesses are the Honorable [First name Family name], and would be addressed as Mr.

Younger daughters of earls are Lady [First name Family name], and rules of address follow the daughters of dukes.

Viscounts and Viscountesses

As with earls, the title is sometimes taken from a geographical name and sometimes a family name.

Titles and forms of address follow marquesses and earls, making them Lord and Lady [Title].

Dowagers viscountesses follow the rule of dowager duchesses.

Courtesy titles stop at the level of earls. The eldest son of a viscount is styled as the Honorable [First name Family name] as are the younger sons of viscounts. They would be addressed as Mr.

Younger daughters of earls are styled as the Honorable [First name Family name], and are addressed as Miss. The eldest daughter would be Miss [Last name] and her younger sisters would be Miss [First name] (ie Miss Emory would be the eldest sister followed by Miss Alexandra and Miss Alexis Emory).

Barons and Baronesses

Barons are the last rank of the peerage. Their names can be derived from geographical location, family name, or other sources.

Titles and forms of address follow marquesses, earls, and viscounts making them Lord and Lady [Title].

Dowagers viscountesses follow the rule of dowager duchesses.

The eldest son of an baron follows the form of address of the eldest son of a viscount. The younger sons of barons and the daughters of barons also follow the rule for viscounts.

If you’re interested in learning more about forms of address, I recommend picking up a copy of Titles and Forms of Address.

I’m giving away two huge prize packs to celebrate the release of my book The Governess Was Wicked thanks to a little help from my author friends. You could win ebooks, signed paperbacks, audiobooks, and an Amazon gift card!. All you have to do is enter here:

September 19, 2016

How the Governesses Came To Be

Ask a writer, “Where do you get your ideas?” And you’re just as likely to get blank stares as you are answers. Many of us have no idea where the ideas come from. They just gel somewhere in the back of our subconscious in some mysterious process even we don’t fully understand because if we did you can bet writing would inspire a lot less hair pulling.

Ask a writer, “Where do you get your ideas?” And you’re just as likely to get blank stares as you are answers. Many of us have no idea where the ideas come from. They just gel somewhere in the back of our subconscious in some mysterious process even we don’t fully understand because if we did you can bet writing would inspire a lot less hair pulling.

If you really want to know where books come from, you’ve got to think of a book like a recipe and ideas like ingredients. You toss a whole bunch of ideas together that you’ve gathered from books, movies, the news, anywhere, and if you’re lucky you wind up with a cake…err…book.

I have no idea where my new Governess series came from, but I can tell you exactly where I was when it sparked. I used to take the 6 train up to the South Bronx every morning to get to my old job. It was an unusually cold day in late October, and I was worrying about what I’d do for NaNoWriMo. Like any good writer, I was armed with my trusty notebook and a pen, ready to write. I just needed an idea.

I got off of the train and headed above ground to wait for the bus that would take me last few miles to work. I probably hunched down into my coat because I’m always cold from October until April. Then, for whatever reason, an idea struck me. What if I wrote a book about a governess?

I love dukes and duchesses and all of the shenanigans they get up to in romance novels, but for a long time I’ve been wanting to change up that story. I’ve always been fascinated by women who lived on the fringes of respectability in Victorian England. Governesses, doctors, teachers, spinsters, small business owners. All of these women were different because all of them did something a woman wasn’t supposed to during this era: they earned their own money.

I love dukes and duchesses and all of the shenanigans they get up to in romance novels, but for a long time I’ve been wanting to change up that story. I’ve always been fascinated by women who lived on the fringes of respectability in Victorian England. Governesses, doctors, teachers, spinsters, small business owners. All of these women were different because all of them did something a woman wasn’t supposed to during this era: they earned their own money.

But despite my fascination with governesses I knew that I couldn’t write just one book and call it a day. With my agent’s very sound business advice to think in series in mind, I began to sketch out basic plot lines for two other governess stories. I gave the heroines the names—Elizabeth, Mary, and Jane—that they would go to publication with. I gave them each a different kind of hero (their men’s names didn’t stay the same). By the time the bus pulled up, I had the kernel of an idea.

I kept working and working at my first governess book until I finished a draft and sent it off to beta readers. It came back bleeding with comments, but there was something in it that seemed worth pursuing so I kept at it. Little by little, a draft emerged. My agent was interested. I wrote my scribbled notes for Mary and Jane’s books into synopses. I rewrote those synopses many, many times, learning and re-learning what would make for a good, sellable book. If I wanted to be a writer who could eventually sell on proposal,

Finally the full first book and two subsequent synopses went out on submission, and a couple months later my governesses found a home and a wonderful editor.

Now that the books are launching this fall, it’s strange to think about the fact that it all started because I was standing at a busy bus stop in the middle of the Bronx, trying to get to work and scrambling to come up with a NaNoWriMo book idea.

Now that the books are launching this fall, it’s strange to think about the fact that it all started because I was standing at a busy bus stop in the middle of the Bronx, trying to get to work and scrambling to come up with a NaNoWriMo book idea.

If you want to write, I may not be able to tell you where to find ideas of your own any more than I can tell you how I come up with mine, but I can give you these two pieces of advice: keep an open, curious mind and never travel without a notebook.

From now until 9/30 I’m giving away two huge prize packs to celebrate the release of The Governess series. Enter to win below!

September 16, 2016

What They Wore: The Governess Was Wicked

I love historical fashion from pantaloons to pelisses, and over the years more and more of it has made its way into my books. Clothing can be a wonderful way to ground a scene in a time and place, and it can also tell you a lot about a character.

Afternoon dress, ca. 1855, French, cotton, from @metmuseum

A photo posted by Really Old Frocks (@reallyoldfrocks) on Jul 25, 2016 at 5:54am PDT

When I started writing Elizabeth Porter, the heroine at the center of The Governess Was Wicked, I knew I’d set myself a particular challenge. Governesses typically wore simple clothing in a limited range of colors (think functional colors like greys and dark blues and greens) and with few embellishments. She would have had a few dresses including her “best” dress that would have been worn to church or on special occasions. Otherwise, her clothing would have had to last as long as possible to maximize on cost.

These dresses are made of much higher quality fabrics than a governess like Elizabeth would have been able to afford, but it gives you an idea of what her wardrobe might have looked like. Dress, ca. 1856, British, from the Metropolitian Museum of Art

Most of what we see in museums are beautiful examples of exquisite — and exquisitely expensive — gowns. The more workman-like dresses weren’t necessarily preserved for history. That means that you’ll see a lot more of Mrs. Norton’s wardrobe when you go to museums than you will Elizabeth’s.

While her clothing might not have been as luxurious and fashion-forward as the woman whose children she educated, a governess did share something in common with her mistress: they both wore the same silhouette.

Cabinet photograph, Aug Linde (photographer), 1850-1860, from the Manchester City Galleries

The late 1850s was characterized by large, bell-shaped skirts that flared out from a tightly cinched waist. One big development in undergarments allowed women to achieve these huge skirts: the cage crinoline. Up until this point, ladies would have piled on petticoats to create a full effect. Although they look horribly impractical to us, crinolines of wire covered with cotton actually created a structure for a dress to lay on top of and flare out from the body.

Cage crinoline, ca. 1862, British, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Crinolines were relatively inexpensive, so women of all classes eventually adopted them (although the massive yards of fabric needed for truly huge skirts would be a fashion statement only very wealthy women could afford).

Dinner dress, 1855–59, British from the Metropolitian Museum of Art

The shape crinolines created was so popular that reports were 200 pound of product was lost in the Staffordshire potteries in 1863 due to the wide skirts of working women accidentally sweeping shelves clean.

Cabinet photograph, H J Whitlock (photographer), 1850-1860, from the Manchester City Galleries

If you’re interested in fashion history (or just really like all of the pretty pictures of dresses I’ve shown), join my Facebook group Really Old Frocks and follow my @reallyoldfrocks Instagram for more beautiful old-fashioned fashion.

And last but not least, I’m giving away two huge prize packs to celebrate The Governess Was Wicked thanks to a little help from my author friends. You could win ebooks, signed paperbacks, audiobooks, and an Amazon gift card!. All you have to do is enter here:

BONUS: I had to include this stereoscopic picture I ran across in doing my research for this article. It’s both creepy and flirtatious with the older gentleman kissing the hand of a young woman who is fending him off coquettishly with her fan.

Stereoscopic photograph & stereograph, 1851-1860, from the Manchester City Galleries

September 12, 2016

The Governess Was Wicked Is Out Now! (Plus a Giveaway)

The wait is over! Today is release day for The Governess Was Wicked, and I couldn’t be happier that the book is now in the hands of readers like you!

Elizabeth Porter is quite happy with her position as the governess for two sneaky-yet-sweet girls when she notices that they have a penchant for falling ill and needing the doctor. As the visits from the dashing and handsome Doctor Edward Fellows become more frequent, Elizabeth quickly sees through the lovesick girls’ ruse. Yet even Elizabeth can’t help but notice Edward’s bewitching bedside manner even as she tries to convince herself that someone of her station would not make a suitable wife for a doctor. But one little kiss won’t hurt…

Amazon | Amazon UK | iBooks | Kobo | B&N

The love story between Elizabeth and Edward was a lot of fun to write, and it also introduces one of my favorite characters I’ve ever written — Lady Crosby (those of you who read The Lady Always Wins will recognize the acerbic matriarch).

The next books in the series, The Governess Was Wanton and The Governess Was Wild, are still available for preorder and will be coming out in October and November. Be sure to sign up for my newsletter so you don’t miss any future release dates!

If you want to learn a bit more about how the entire series came to be, First Draught dedicated an entire episode to my path to publishing story:

I’m also over on T.J. Kline’s blog where she grilled me about the books and gave me a quick pop quiz.

Plus I’m on XOXO After Dark talking about dream casting all my heroes and heroines.

And last but not least, I’m giving away two huge prize packs thanks to a little help from my author friends. You could win ebooks, signed paperbacks, audiobooks, and an Amazon gift card!. All you have to do is enter here: