Julia Kelly's Blog, page 12

November 27, 2018

Your First Look at an Entrancing, Heartbreaking Novel of World War II

Told from the present-day perspective of a British antiques dealer who specializes in helping families sell the contents of estates, The Light Over London transports readers to World War II London through forgotten treasures. Please enjoy this early look at this entrancing, heartbreaking novel, reminiscent of Martha Hall Kelly’s Lilac Girls.

November 25, 2018

The 12 Days of Christmas Reads

It’s the most wonderful time of year—and the most wonderful time of year to be a reader!

Last year I celebrated the Christmas season with my 12 Days of Christmas Reads. I highlighted 12 books with holiday themes that I thought readers would enjoy, from romance to historical mystery. This year I’ll be bringing the 12 Days of Christmas Reads back with an brand-new selection of books from an even wider range of genres.

The 12 Days of Christmas Reads kicks off on December 3rd. You can catch all of the Christmas cheer by checking in every day, keeping an eye on my 12 Days of Christmas Reads page that’s updated with a new post every day, or by signing up for my newsletter.

October 10, 2018

The Women Who Rode Bikes for Britain

Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

In researching my upcoming release, The Light Over London , I was continually amazed at the many—often unsung—ways women contributed to the war effort in Britain during World War II. The Lightseekers is an ongoing series of articles that highlights some of their work and the ways they brought light to Britain in one of its darkest times.

If you’re looking for bravery and glamor in equal parts, look no further than the motorcycle dispatch riders of the Women’s Royal Navy Service (WRNS), popularly known as the Wrens. This group of women played a vital role during World War II, providing reliable communication for the Royal Navy and admiralty in a time when technology could too easily fail.

The history of female dispatch riders starts far earlier than World War II. The first group of Wrens who rode motorcycles for Britain was formed in 1917 during the World War I. They were disbanded in 1919, but the service was revived in 1939 when Britain again found itself at war. All able-bodied seamen were needed in the Royal Navy, and the women’s auxiliary adopted the famous slogan “Join the Wrens and Free a Man for the Fleet.”

Seen a posh and glamorous with their flattering uniforms and upper-crust recruits, many girls who wanted to join up clambered to become a Wren. But when it came to becoming a dispatch riders, only those women with prior motorcycle riding experience were initially selected. (This was in part because riders had to be able to maintain their bikes as well as ride.) That meant that before World War II, which so many of us see as a turning point in the activities that were acceptable for women, women were riding bikes—including some well-known competition riders from local race circuits.

The primary role of a dispatch rider was to ferry orders and messages between the Royal Navy and admiralty’s offices and bases. They worked in sometimes harrowing conditions, during Blitz conditions and in all weather.

Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

One story of a Wren’s bravery is that of Wren McGregor. She set out to deliver a message to her commander in Plymouth, which was under a bombing raid. En route, her motorcycle was hit by a bomb. Incredibly, she was uninjured and left the destroyed motorcycle by the side of the road, running a half mile to her headquarters to deliver the message with bombs falling around her. With her task complete, she volunteered to go back to work. Unsurprisingly, McGregor was awarded a British Empire medal for bravery.

The accomplishments and importance of the dispatch riders was so great that they became the subject of parliamentary debate on July 6, 1943. Lord Brabazon of Tara criticized the Royal Air Force (RAF) for not making use of women as dispatch riders. “We, who live in London, see many members of the W.R.N.S. going about on motor bicycles in all sorts of weather,” he said. “We see them on the streets of London every day. Figuratively, whenever I see one I take my hat off to her—but only figuratively.

Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

More than 100 Wrens who were motorcycle dispatch riders lost their lives riding through the Battle of Britain and other conflicts. The subjects of photo spreads and press interest just as they were the recipients of medals for bravery, they became famous across the world as an example of the work women did during the war.

Read every story of the The Lightseekers in the series archive . You can also learn more about their stories by following the hashtag #TheLightseekers on Instagram , Facebook , Twitter , and Pinterest .

October 8, 2018

The Light Over London Goodreads Giveaway

Is your TBR pile looking a little thin. (Yeah, I laughed at that too.) Whether you've got an epic stack of books on your nightstand or you're looking to add to your collection, I'm here to help with another The Light Over London Goodreads giveaway!

Up for grabs are 100 advance reader copies of The Light Over London. All you have to do is click here to enter to win one. (You can also follow me on Goodreads for updates about my book.)

Now for the fine print: The contest is for U.S. readers only and is open until October 15.

Good luck!

October 2, 2018

What I Read: July to September 2018

What a three months of reading!

I mentioned the other day that I’ve started a brand-new podcast with my sister Justine, who is the woman behind the blog I Should Read That. I’ve been reading a lot for project, PLUS I also handed in the first draft of a new book to editor. That means I’ve been binging all of the books I haven’t been able to read while working.

Here’s a look at what I’ve read (and loved) this last quarter:

If you want to follow along with me as I read my way to the end of the year, you can find me on Goodreads. And please, if you’ve read any of these books or have a recommendation for me, leave a comment!

September 27, 2018

The Women Who Delivered Planes

In researching my upcoming release, The Light Over London , I was continually amazed at the many—often unsung—ways women contributed to the war effort in Britain during World War II. The Lightseekers is an ongoing series of articles that highlights some of their work and the ways they brought light to Britain in one of its darkest times.

The men of the Royal Air Force and the Fleet Air Arm were not the only pilots who flew during World War II. Thanks to the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), a group of civilian flyers otherwise considered unsuitable for service because of age, ability, or gender made an incredibly important contribution to the war.

While the ATA may have originally been conceived of as a support group to transport personnel, mail and medical supplies, it soon became clear that pilots were needed for a serious role: transporting the RAF’s aircraft from factories to bases. They were delivering the planes that protected the Home Front in the Battle of Britain and fought over seas.

Before the outbreak of the war, there was major resistance to the idea of women flying planes. Although women could and did fly before the war, critics believed that they would be taking men’s jobs f they were used for this purpose in the ATA. However, a few months into the war, in December 1939, the ATA caved. Pauline Gower was appointed to head up a newly formed women’s section of the service. An accomplished circus pilot between the wars, Gower was firm in her belief that women could and should fly.

The first female pilots of the Air Transport Auxiliary from the collections of the Imperial War Museums.

“Some people believe women pilots to be a race apart, and born ‘fully fledged,’” she said. “Women are not born with wings, neither are men for that matter. Wings are won by hard work, just as proficiency is won in any profession.”

Gower selected the first eight women to be appointed to the ATA. They were accepted on January 1, 1940, and were trained up at Hatfield. Over the course of the war, their numbers swelled to include over 160 female pilots. Nicknamed the “Attagirls,” these women hailed from Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, the U.S., the Netherlands, Poland, Argentina, and Chile.

Although they were restricted to non-combat roles in their duties as trainers and transporters, the Attagirls flew every time of aircraft used by the RAF and the Fleet Air Arm. This included some of the war’s most famous planes, Hurricanes and Spitfires.

ATA personnel Lettice Curtis, Jenny Broad, Audrey Sale-Barker, Gabrielle Patterson, Pauline Gower.

While their roles might have been restricted, that didn’t mean that the danger was any less. The women in the ATA were flying aircraft in open skies, and 15 of them lost their lives during the war.

If you’re interested in the incredible Attagirls and the work they did, British Airways has created a photo gallery featuring archive images of them.

Read every story of the The Lightseekers in the series archive . You can also learn more about their stories by following the hashtag #TheLightseekers on Instagram , Facebook , Twitter , and Pinterest .

September 26, 2018

A Brand-New Podcast for Booklovers

One of the best things about having a sister who is also a booklover—and the blogger I Should Read That—is that we’re never at a loss for book recommendations. But when it comes to actually reading those recommendations, we are both guilty of major failure.

To solve that problem (and tackle our growing TBR lists), we’re launching a new podcast. It’s called You’re Never Going to Read This. Each episode we recommend a book each from one of the many genres we love in hopes that we can convince the other to finally sit down and read it.

You can listen to a trailer of You’re Never Going to Read This on Apple Podcasts and all major podcasting platforms. You can also click here to find out a little more about the show on our website.

September 13, 2018

The Light Over London Goodreads Giveaway

Autumn is my favorite season. The cozy clothes, leaves crackling under foot, and plenty of good books.

If you're looking for something fresh for your TBR this fall, you're in luck. I've got another The Light Over London Goodreads giveaway to tell you about!

Up for grabs are 100 advance reader copies of The Light Over London. All you have to do is click here to enter to win one. (You can also follow me on Goodreads for updates about my book.)

Now for the fine print: The contest is for U.S. readers only and is open until September 24.

Good luck!

September 6, 2018

The Woman Who Was “The Real Force Behind Churchill”

In researching my upcoming release, The Light Over London , I was continually amazed at the many—often unsung—ways women contributed to the war effort in Britain during World War II. The Lightseekers is an ongoing series of articles that highlights some of their work and the ways they brought light to Britain in one of its darkest times.

She was married to the most famous man in the world during World War II, but Clementine Churchill did far more than stand by her husband. She was an active, dynamic part of his war efforts from handling informal diplomatic duties to managing the man himself.

Born April 1, 1885, Clementine Ogilvy Hozier was the daughter of Henry Montague Hozier and Lady Blanche Hozier, although there is question about her actual paternity given her mother’s well-known affairs. (Lady Blanche is reported to have managed ten lovers at once, although verifying this is, understandably, somewhat difficult.)

Clementine was educated at home and then at schools before attending the Sorbonne in Paris. At 18, she became secretly engaged to Sir Sidney Peel—twice—who had fallen in love with her. However, she would not marry him.

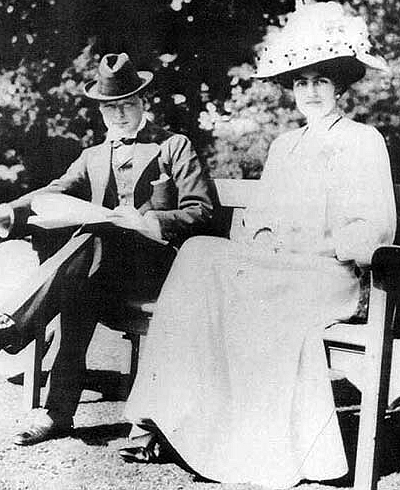

Winston Churchill (1874-1965) with fiancée Clementine Hozier (1885-1977) shortly before their marriage in 1908, Wikimedia Commons

Clementine met Winston Churchill in 1904 at a ball at Crewe House. Winston thought her beautiful at this first meeting. But in 1908 they would meet again, this time at a party hosted by one of her distance relatives, and this time he recalled that she’d become an intelligent woman of character. He proposed five months later at Blenheim Palace, and they were married just over a month later on September 12.

During World War I, Clementine distinguished herself with her efforts on the home front. She organized canteens for munition workers in London and was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1918 in gratitude for her work.

When World War II broke out, Clementine resumed her war work with the Red Cross, serving as chairman of the Red Cross Aid to Russia Fund. She was also the President of the Young Women’s Christian Association War Time Appeal (YWCA) and the chairman of the Maternity Hospital for the Wives of Officers, Fuller Chase. She was also a fire watcher during the Blitz and was held up as an example of how British women could pull together and help their country.

The wife of the Prime Minister, Mrs Clementine Churchill, inspects members of the ATS at the Royal Artillery Experimental Unit, Shoeburyness, Essex, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

However, some of her most important work during the war came when Winston became prime minister on May 10, 1940. Judith Evans, the house and collections manager at the Churchills’ home Chartwell, offered perspective on Clementine’s role in an interview in the Telegraph. [LINK] “She was quite a big player,” said Evans. “She helped maintain difficult relationships and worked quietly behind the scenes for the war effort.”

Not only did Clementine act as a hostess and a de facto diplomat, she was her husband’s confidant. So close was their relationship that she had a room of her own in his War Rooms, a bunker just to the east of St. James Park in London that became the nerve center of Britain’s wartime strategy.* She was called to comfort Winston the night before the D-Day landings when her husband was sitting despondent in the operations rooms. Although they presented a united front in public, she was also one of the few people who could openly criticize his ideas in private. She held him accountable and supported him during one of the most uncertain times in British history.

Winston’s chief of staff, General Ismay would later say that the “history of Winston Churchill and of the world would have been a very different story” without Clementine. And Winston Churchill wrote that, Clementine made “my life and any work I have done possible.”

Lady Clementine Churchill, Baroness Spencer-Churchill and a life peer in her own right, outlived her husband by 12 years. She died in 1977 in her London home at the age of 92.

Read every story of the The Lightseekers in the series archive . You can also learn more about their stories by following the hashtag #TheLightseekers on Instagram , Facebook , Twitter , and Pinterest, and sign up for Julia's newsletter to receive every episode of The Lightseekers.

*The Churchill War Rooms are fascinating. The underground bunker that was the nerve center of Britian’s war effort was mothballed after the war ended in 1945. The Imperial War Museum has made considerable effort to restore and display it as it would’ve appeared during the war. If you choose to go, which I highly recommend, time your arrival for the opening as a limited number of people can be in the exhibition space at a given time. Plan to give yourself a couple of hours to go through the maze of rooms.

August 23, 2018

The Woman Who Held Paris

In researching my upcoming release, The Light Over London, I was continually amazed at the many—often unsung—ways women contributed to the war effort in Britain during World War II. The Lightseekers is an ongoing series of articles that highlights some of their work and the ways they brought light to Britain in one of its darkest times.

Noor Inayat Khan was one of the most well-known female spies of World War II, but little about her background makes her the obvious choice for espionage. Yet an artless personality hid a steeliness that led her to defy her superiors and remain at her station in Paris during the height of the war, continuing the dangerous work of operating a radio to enable the British to continue to supply the French Resistance and save the lives of downed pilots.

Born on New Year’s Day in 1914, Khan was the daughter of Hazrat Inayat Khan and Amina Sharada Begum (originally known as Ora Ray Baker). After living in Moscow, the family moved to France and then to Britain where Harat Inayat Khan would become leader of the Sufi Order, a form of Islam that preached love, tolerance, and pacifism.

Hon. Assistant Section Officer Noor Inayat Khan (code name Madeleine), courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

It’s hardly surprising then that Harat Inayat Khan’s daughter would grow up to become a pacifist herself. However, in 1939, as Germany began to invade its neighbors, she decided that she needed to act. After enrolling to train as a Red Cross nurse in France but narrowly escaping the German invasion on one of the last boats to evacuate British citizen, Khan enlisted in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAFs). She was not British, and neither did she accept Britain’s policies wholesale; she told her recruitment officers that when the war ended she would campaign for Indian independence. However, she was accepted and selected to train as a wireless operator. Then, in October 1942, she was recruited by the Special Operations Executive (SOE), likely for her radio skills and her fluency in English, French, Spanish, and German.

While Khan excelled at all aspects of radio operation, there were concerns about how well she would hold up in the field. Her superiors believed she was too artless to be an agent, and she frightened easily. One of her officers recalled her reaction when she was put through the paces in a mock interrogation:

She was so overwhelmed, nearly lost her voice. As it went on she became practically inaudible. Sometimes there was only a whisper. When she came out afterwards, she was trembling and quite blanched.

However, despite some reservations about her suitability, the 29-year-old Khan was parachuted to Occupied Paris where wireless operators were desperately needed in 1943. She was given the code name Madeline and became the first female wireless operator stationed in France.

She initially made contact with PROSPER, a network bringing in arms from Britain for the French Resistance. However, shortly after she arrived, a double agent betrayed PROSPER and almost all of the high-level members of the network were arrested. The SOE ordered Khan to return to Britain, but she refused, going rogue and continuing to broadcast. Soon she was the only active wireless operator in the area surrounding Paris.

Life on the run meant zipping around on a bicycle, hanging her conspicuous aerial wherever it might be reasonably hidden, transmitting her information, and quickly breaking her radio down before the Germans could track her signal and find her. Her broadcasts mostly concerned drops of arms and money, as well as the status of the resistance networks. She is also believed to have been “instrumental in facilitating the escape of 30 Allied airmen shot down in FRANCE,” according to a posthumous commendation.

Khan’s bravery was unquestionable. Wireless radios were large and bulky, and not discreet even when broken down into their parts. One story goes that she was riding the Metro in Paris when she was stopped by two German officers who wanted a look at her case. She told them that her radio was a film projector, and even opened it up to let them see. Incredibly, they didn’t recognize the radio in front of them or the woman named Madeline whom the Germans were so eager to find.

Ultimately, Khan was betrayed by another woman who sold Khan’s address to the Germans in October of 1943. When Khan got back to her apartment, the Gestapo was waiting for her. Not only did they find her transmitter, but they also found a school copybook in which she’d meticulously recorded all of her transmissions and security checks. This was directly against SOE orders, although there is some dispute about whether she misunderstood the SOE instruction, “Be very careful in the filing of your messages” to mean recording them down rather than transmitting, or “filing” them.

Either way, the German’s arrested Khan and interrogated her. They would go on to use her notebook to transmit messages as her until early 1944 when the SOE realized that something was amiss. Khan tried multiple times to escape from her prison in Paris but each time was captured and returned to her cell. Eventually she was taken to Pforzheim, a German prison, where she was badly mistreated and spent most of her days heavily shackled.

On September 11, 1944, she and three other female prisoners were sent to Dauchau. Two days later, Khan and the other women were executed. Her last reported word was, “Liberte.”

No one knew what happened to the operative known as Madeline until after the war when Vera Atkins, a woman who had worked with Khan in the SOE, went searching for the agents who had gone missing in the war. Atkins realized that Khan had been mistakenly identified as a woman who had actually been killed at Natzweiler. Atkins was able to learn the truth of Khan’s death and inform the War Office which, in turn, told her family.

Khan was posthumously honored with an MBE, the British George Cross, and the French Croix de Guerre with gold star. Although her months operating in France were short, the information she was able to broadcast was considered invaluable during a time of extreme danger. Her incredible bravery and dedication to the cause is as remarkable as her death was tragic.

Today she is remembered with a memorial bust of Khan—the first dedicated to an Asian woman—stands in Gordon Square in the Bloomsbury neighborhood of in London, as well as a number of plaques and other commemoration across Britain.

Read every story of the The Lightseekers in the series archive. You can also learn more about their stories by following the hashtag #TheLightseekers on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and Pinterest.